Abstract

Rice dwarf virus (RDV) is a member of the genus Phytoreovirus, which is composed of viruses with segmented double-stranded RNA genomes. Proteins that support the intercellular movement of these viruses in the host have not been identified. Microprojectile bombardment was used to determine which open reading frames (ORFs) support intercellular movement of a heterologous virus. A plasmid containing an infectious clone of Potato virus X (PVX) defective in cell-to-cell movement and expressing either β-glucuronidase or green fluorescent protein (GFP) was used for cobombardment with plasmids containing ORFs from RDV gene segments S1 through S12 onto leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana. Cell-to-cell movement of the movement-defective PVX was restored by cobombardment with a plasmid containing S6. In the absence of S6, no other gene segment supported movement. Identical results were obtained with Nicotiana tabacum, a host that allows fewer viruses to infect and spread within its tissue. S6 supported the cell-to-cell movement of the movement-defective PVX in sink and source leaves of N. benthamiana. A mutant S6 lacking the translation start codon did not complement the cell-to-cell movement of the movement-defective PVX. An S6 protein product (Pns6)-enhanced GFP fusion was observed near or within cell walls of epidermal cells from N. tabacum. By immunocytochemistry, unfused Pns6 was localized to plasmodesmata in rice leaves infected with RDV. S6 thus encodes a protein with characteristics identical to those of other viral proteins required for the cell-to-cell movement of their genome and therefore is likely required for the cell-to-cell movement of RDV.

Rice dwarf virus (RDV) is a member of the genus Phytoreovirus, family Reoviridae, and is the cause of a serious rice disease in southern Asia (3). The sequences of two isolates have been determined (43, 51). The genome of RDV is composed of 12 separate segments of double-stranded RNA (3). Seven structural proteins and at least six nonstructural proteins are encoded by the 12 genome segments (S1 to S12). The seven structural proteins are products of segments S1, S2, S3, S5, S7, and S8 (27, 31). Coexpression of P3, the major core structural protein, and P8, the outer capsid structural protein, in transgenic rice plants or insect cells results in the formation of double-shelled virus-like particles (16, 52). The six nonstructural proteins are products of S4, S6, and S9 through S12 and have molecular masses of 83, 56, 49, 35, 23, and 34 kDa, respectively (27, 31). The functions of these nonstructural proteins are mostly unknown, although the S11 protein product (Pns11) is known to bind nucleic acid (47) and Pns6 increases RDV accumulation and symptom severity (2). No viral protein necessary for virus cell-to-cell movement has been identified for members of the genus Phytoreovirus. Due to the double-stranded RNA structure of the genome and the inability to mechanically transmit the virus, infectious clones for RDV and other plant reoviruses have not been reported. Therefore, other methods are necessary to determine the function of genes from viruses within this genus.

Cell-to-cell movement by plant viruses is a requirement for the systemic infection of plants. Viral proteins essential for the cell-to-cell movement of the virus often have the characteristics of altering the size exclusion limits of the plasmodesmata (PD) in the cell wall (reviewed in references 11, 17, 18, 23, and 49) and in interacting with cytoskeletal elements (reviewed in references 1, 33, 35, and 50). Recent studies have identified genes encoding the movement protein (MP) of a virus by expressing the gene in the presence of a mutant virus that cannot move from cell to cell, in some instances when the MP is from a virus belonging to a different genus (9, 12, 13, 22, 28, 29, 30, 37, 38, 40, 41). The complemented movement is observed either by use of a mutant chimeric virus created by substituting a putative MP-encoding gene into the genome of a movement-defective virus (9, 13, 30, 38) or by bombardment or transformation of a plant with a plasmid expressing the putative MP and bombardment with a plasmid expressing a movement-defective virus (12, 22, 26, 28, 29, 40, 41). These complementation analyses are efficient and reliable approaches for identification of molecular components involved in the transport of viral RNA.

We have utilized the complementation approach to identify RDV movement proteins. The 12 RDV genome segments were cloned individually into a plant transient-expression vector. Some or all of these plasmids were individually introduced into cells of Nicotiana benthamiana, Nicotiana tabacum, or Oryza sativa leaves by microprojectile bombardment together with plasmids yielding movement-defective, but replication-competent, β-glucuronidase (GUS)-tagged or green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged Potato virus X (PVX). The movement and subcellular location of virus-encoded reporter protein were monitored by visualizing GUS activity or GFP fluorescence. In addition, a fusion of S6-encoded protein with enhanced GFP (eGFP) was monitored by confocal laser scanning microscopy after bombardment of Nicotiana tissue, and the location of the unfused S6-encoded protein was monitored by immunocytochemistry and electron microscopy after infection of O. sativa with RDV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

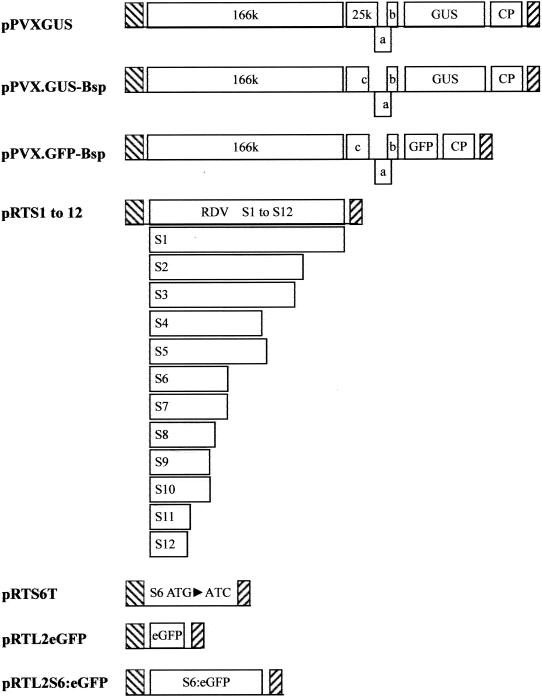

RDV gene segments S1 through S12 were individually cloned from the Fujian isolate and sequenced by using a previously described procedure (51). Restriction fragments containing open reading frames (ORFs) of each segment were ligated into a Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S-based pRT transient-expression vector digested with BamHI and PstI (42). The recombinant plasmids containing RDV gene segments were designated pRTS1 to pRTS12 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of plasmids used in this study. ▧, CaMV 35S promoter; ▨, nopaline synthase terminator; 166k, 166 kDa-protein; 25k, 25-kDa protein; a, 12-kDa protein; b, 8-kDa protein; c, 25-kDa mutant; CP, coat protein; ORFs are shown as rectangles, and the mutant S6 ORF lacking an ATG is shown as a line. pPVX.GUS-Bsp and pPVX.GFP-Bsp were provided by S. Y. Morozov, and pPVXGUS was provided by D. Baulcombe.

The start codon for S6 ORF translation was altered to ATC by PCR with two primers: forward primer 5′-AATTCACCATCGACACAGAA-3′, including the 5′ portion of the ORF (the mutated start codon position is in boldface), and reverse primer 5′-GAGCTGCAGCTGCCCATTAGTCGACCCAG-3′, based on the S6 sequence of the RDV Fujian isolate (GenBank accession no. U36564). High-fidelity Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) was used in the PCRs. The amplified PCR product was ligated into pGEM3Zf(+) digested with HincII. After sequencing, the mutated S6 sequence was digested with BamHI and PstI and ligated into the pRT vector digested with BamHI and PstI to yield pRTS6T (Fig. 1).

Movement-defective GUS- or GFP-tagged PVX, designated pPVX.GUS-Bsp or pPVX.GFP-Bsp (Fig. 1), respectively, and provided by S. Y. Morozov, were used for complementation experiments (28, 29). Both contain the same frameshift mutation at nucleotide position 4959 within the 25-kDa protein ORF, resulting in the absence of 72 C-terminal amino acid residues in the translated protein. The cell-to-cell movement of infectious virus from these constructs was complemented by active 25-kDa protein and other movement-associated proteins (28). pPVXGUS, a derivative of pGC3 (5), was provided by David Baulcombe. All of the PVX constructs reside behind a CaMV 35S promoter (5, 28, 29).

A two-step recombinant PCR method (39) was used to generate the Pns6-eGFP (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) fusion ORF, with the following modifications. Pns6 was amplified by using high-fidelity Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene) in the presence of a forward primer (S6 forward primer, 5′-AAAATGGACACAGAAACTCTTTGC-3′) and a reverse primer containing complementary sequences from the 3′ end of the S6-coding sequence and the 5′ end of the eGFP-coding sequence (S6 reverse primer, 5′-CCTCGCCCTTGCTCACCATTTTGTACACGGTAATAGCA-3′). Similarly, the eGFP-coding region was amplified by using a forward primer complementary to the S6 reverse primer (eGFP forward primer, 5′-TGCTATTACCGTGTACAAAATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGG-3′) and a reverse primer containing a KpnI site (eGFP reverse primer, 5′-GTCGGTACCTTTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCC-3′). The resulting PCR fragments containing the S6 and eGFP ORFs were purified by using a PCR product purification kit (Plasmid Midi; Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). The purified PCR products and the S6 forward and eGFP reverse primers were then used in a second PCR to create the S6-eGFP fusion with a KpnI site at the 3′ end. After purification and digestion with KpnI, the resulting chimeric cDNA was ligated into the plant transient-expression vector pRTL2 (4, 34), previously digested with KpnI and NcoI, to yield pRTL2S6:eGFP (Fig. 1).

All constructs were sequenced by automated dye-terminator sequencing (model 377; PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's protocol to confirm sequence authenticity.

Identification of N. benthamiana leaf development stages.

Carboxyfluorescein (CF) dye was used to identify source and sink leaves on N. benthamiana plants. CF dye was applied to the petioles of the most mature leaves, and fluorescence was monitored with a UV lamp. CF dye moves through the phloem in a source-to-sink direction, unloading in sink, but not source, leaves (32, 36).

Inoculation of Nicotiana and Oryza leaves.

Inoculation of N. benthamiana, N. tabacum, and O. sativa leaves by particle bombardment was performed with a high-pressure helium-based apparatus and the flying disk method (model PDS-1000; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). For each series of bombardments, 5 μl of plasmid DNA (at 1.0 μg/μl) was precipitated onto 3 mg of gold particles (1-μm diameter; Bio-Rad) in the presence of a solution of calcium chloride (2.5 M) and spermidine (0.1 M). For the cobombardment, 2.5 μg of DNA of each plasmid was mixed and applied to gold particles in the same way as for the single bombardment. The plasmid DNA-coated gold particles were washed once with 70% ethanol and then maintained in suspension in absolute ethanol. After sonication, 20 μl of this mixture was placed on plastic flying disks and used for bombardment when the particles had dried. Source or sink leaves of N. benthamiana and source leaves of N. tabacum or O. sativa were placed in the center of a plastic petri dish and bombarded on a solid support at a target distance of 8 cm. Bombardment was done with a pulse of 1,100 kPa of helium gas in a vacuum chamber. For each of the constructs used in this research, the bombardment was repeated at least three times.

Histochemical analysis of GUS activity.

Leaves were sampled at 30 h postbombardment for N. benthamiana and at 72 h postbombardment for N. tabacum. GUS activity was monitored by histochemical detection (20) with the following modification. Samples were infiltrated with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-glucuronide (X-Gluc), at 600 μg/ml, in a solution containing 0.115 M phosphate buffer [pH 7.0], 3 mM potassium ferricyanide, and 10 mM EDTA. The phosphate-ferricyanide-EDTA mixture limits the diffusion of the intermediate products of the reaction (8). After incubation overnight at 37°C, leaves were fixed in 70% ethanol and examined by light microscopy.

Confocal microscopy.

The bombarded tobacco leaves expressing eGFP or fused Pns6-eGFP were harvested at 24 h postbombardment and examined with a confocal imaging system (model 1024ES; Bio-Rad) attached to an upright microscope (Axioskop; Zeiss, Thornwood, N.Y.) equipped with 60× objective lens (Zeiss) as described previously (6). Serial optical sections were obtained at 0.5-μm intervals, and the projections of optical sections were combined on a Power Edge 2200 computer (Dell, Austin, Tex.) by using Lasersharp software version 3.1 (Bio-Rad).

Immunocytochemical electron microscopy.

Small pieces of tissue were excised from RDV-infected and noninfected O. sativa leaves and fixed in a solution of 1% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde and 4% (wt/vol) formaldehyde in 100 mM sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) for 3 h. After dehydration in a graded acetone series, the samples were embedded with Epon-araldite and polymerized at 60°C as described previously (21). For immunogold labeling, ultrathin tissue sections, attached to 200-mesh nick grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, Pa.), were floated on a drop of blocking solution containing 1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.) in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) (10 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl [pH 7.4]) for 20 min. The sections were then incubated for 2 h at room temperature with rabbit polyclonal antiserum against Pns6, which was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Y. Li, unpublished results), diluted 1:200 (vol/vol) in the blocking solution. The sections were rinsed four times (10 min each time) in TBS and then incubated for 1 h with goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin linked with 15-nm-diameter colloidal gold particles (GAR-gold, EM CARIgG15; Biocell Research Laboratories, Cardiff, United Kingdom) and diluted 1:30 in TBS. The sections were then washed in TBS and double-distilled water. After drying, the sections were contrasted with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined with an electron microscope (model EM10; Zeiss) at 80 kV. The specificity of immunogold labeling was determined by replacing primary antibody with rabbit preimmune serum or buffer.

RESULTS

RDV gene segments that support cell-to-cell movement of a movement-defective PVX in N. benthamiana.

To identify genes involved in RDV cell-to-cell movement, RDV ORFs were individually inserted into the plant expression vector pRT (42), and, together with a movement-defective PVX expressing GUS (pPVX.GUS-Bsp [Fig. 1]), they were used for cobombardment onto detached source leaves from N. benthamiana. In order to verify expression of the constructs which we used in cobombardment in the tissues, total protein extracts from bombarded N. benthamiana leaves were detected by Western blotting with RDV P3-, P8-, and P10-specific antisera. The results showed that RDV P3, P8, and P10 were expressed in the bombarded N. benthamiana leaves (results not shown). In addition, plasmids pPVXGUS (a plasmid yielding virus capable of cell-to-cell movement [Fig. 1]) and pPVX.GUS-Bsp were used for bombardment onto N. benthamiana leaves in the absence of RDV sequences.

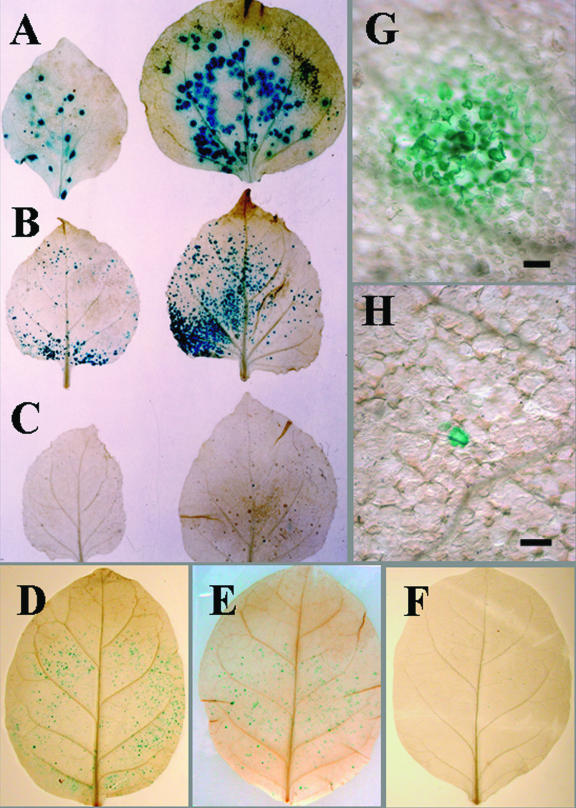

Leaves bombarded with movement-competent pPVXGUS displayed large blue foci after histochemical staining (Fig. 2A). Cobombardment with pPVX.GUS-Bsp and plasmids containing individual ORFs from S1 through S12 showed that only S6 allowed the production of multicellular blue foci on N. benthamiana leaves (Fig. 2B and G and data not shown). The blue foci produced in the presence of pRTS6 were smaller and displayed enhanced signal along minor veins compared with foci produced by the movement-competent virus (Fig. 2A and B and data not shown). In contrast with results from cobombardment with pPVX.GUS-Bsp and pRTS6, bombardment with pPVX.GUS-Bsp alone yielded only small blue foci that were very difficult to see (Fig. 2C and H). These small blue foci represented initially bombarded individual cells. On rare occasions visible blue foci were observed after bombardment with pPVX.GUS-Bsp. These blue foci may have been formed by a small group of simultaneously infected epidermal or mesophyll cells or by passive diffusion of the chromogenic dye between cells, despite our use of a method to limit diffusion (26, 28, 29). These results indicate that pPVX.GUS-Bsp was unable to move from cell to cell. The same pattern of staining was produced after bombardment with a plasmid expressing only the GUS gene (data not shown) (28). The ability of the S6 segment to complement the movement of the movement-defective PVX was similar in sink and source leaves of N. benthamiana (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Cell-to-cell movement of a movement-defective PVX determined by transcomplementation with the S6 gene product of RDV in source leaves of N. benthamiana and N. tabacum. Leaves of N. benthamiana and N. tabacum were bombarded with pPVX.GUS-Bsp (movement defective) alone or with pPVX.GUS-Bsp and pRTS6 or pPVXGUS (movement capable). Bombarded leaves of N. benthamiana and N. tabacum were harvested and stained at 30 h or 3 days postbombardment, respectively. They were analyzed by histochemical staining and light microscopy. (A) N. benthamiana leaves bombarded with pPVXGUS, showing large blue infection foci (mean lesion size, 1,650.5 μm; standard deviation, 352 μm; standard error, 82 μm); (B and G) N. benthamiana leaves bombarded with pPVX.GUS-Bsp and pRTS6, showing intermediate-sized blue infection foci (mean, 683.3 μm; standard deviation, 168 μm; standard error, 27 μm [shown in panel B]); (C and H) N. benthamiana leaves bombarded with pPVX.GUS-Bsp alone, showing single-cell infections (mean, 38.5 μm; standard deviation, 9.3 μm; standard error, 1.8 μm [shown in panel C]); (D, E, and F) N. tabacum leaves bombarded with pPVXGUS, pPVX.GUS-Bsp and pRTS6, and pPVX.GUS-Bsp, respectively. Bars, 50 μm.

To determine whether the S6 segment complemented the movement of the movement-defective PVX through its encoded protein, the translational start codon of the S6 ORF was altered from ATG to ATC (Fig. 1). This mutant S6 ORF could not complement the cell-to-cell movement of the movement-defective PVX (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Analysis of transcomplemented cell-to-cell movement by a movement-defective PVX in the presence of a translation-incompetent RDV S6 ORF or a Pns6-eGFP fusion in source leaves of N. benthamiana. The bombarded leaves were harvested and analyzed at 30 h postbombardment by histochemical staining and light microscopy. (A) Leaves bombarded with pPVX.GUS-Bsp (movement defective) and pRTS6T (translation incompetent), showing infection in a single cell. (B) Leaves bombarded with pPVX.GUS-Bsp, showing infection in a single cell. (C and D) Leaves bombarded with pPVX.GUS-Bsp and pRTL2S6:eGFP (Pns6-eGFP fusion) and with pPVX25.GUS-Bsp and pRTS6, respectively, showing multicellular blue infection foci. Bar, 50 μm.

Analysis of the ability of the RDV S6 ORF to complement the movement of movement-defective PVX in the more restrictive hosts N. tabacum and O. sativa.

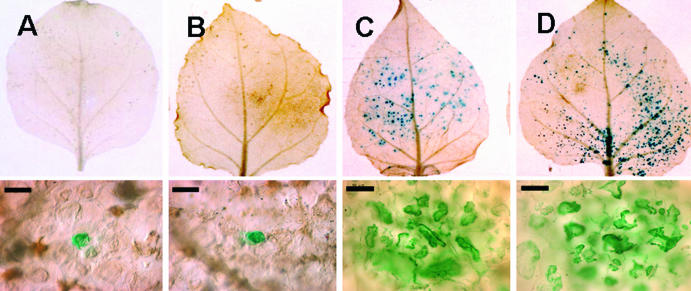

N. benthamiana is a permissive host to many plant viruses (7), and thus the results described above may reflect this host's ability to allow complementation that is not normally observed in more limiting hosts. To determine whether S6 could complement the cell-to-cell movement of movement-defective PVX in a host with a more limited susceptibility to viruses, pPVX.GUS-Bsp or pPVX.GFP-Bsp was used for cobombardment with pRTS6 onto source leaves of N. tabacum. Leaves bombarded with pPVX.GUS-Bsp and pRTS6 displayed blue foci with a size similar to that of foci produced by pPVXGUS (compare Fig. 2D and E). Leaves bombarded with pPVX.GUS-Bsp alone yielded mostly microscopic single-cell blue foci (Fig. 2F and data not shown). The results of multiple bombardments with the different combinations of plasmids are summarized in Table 1. Multicellular expression was also observed when pPVX.GFP-Bsp was used for cobombardment with pRTS6 onto leaves of N. tabacum (Fig. 4B).

TABLE 1.

Transcomplemented movement of movement-defective PVX (pPVX.GUS-Bsp) in leaves of N. tabacum and N. benthamiana in the presence of the S6 segment of RDV or the S6-eGFP fusiona

| Plasmid(s) used for bombardment | No. (% of total foci) of foci with the following no. of infected cells:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2-5 | 6-10 | ≥11 | |

| cpPVXGUSb | 0 (0) | 6 (20) | 20 (67) | 4 (13) |

| pPVX.GUS-Bsp + pRTS6b | 3 (10) | 11 (37) | 13 (43) | 3 (10) |

| pPVX.GUS-Bspb | 29 (97) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| pPVX.GUS-Bsp + pRTS6c | 2 (2) | 42 (39) | 37 (34) | 26 (24) |

| pPVX.GUS-Bsp + pRTL2S6:eGFP fusionc | 1 (1) | 47 (43) | 36 (33) | 25 (23) |

Leaves were bombarded with pPVXGUS, pPVX.GUS-Bsp and pRTS6 (containing the S6 segment), pPVX.GUS-Bsp and the pRTL2S6:eGFP fusion, or pPVX.GUS-Bsp alone. The bombarded leaves of N. tabacum and N. benthamiana were harvested and analyzed by histochemical staining and light microscopy.

Data were recorded at 3 days postbombardment of N. tabacum leaves.

Data were recorded at 30 h postbombardment of N. benthamiana leaves.

FIG. 4.

Transcomplemented cell-to-cell movement of movement-defective pPVX.GFP-Bsp in the presence of the S6 gene product of RDV in source leaves of N. tabacum. Leaves were bombarded with pPVX.GFP-Bsp (movement defective) alone or with pPVX.GFP-Bsp and pRTS6. Images were taken with a confocal laser scanning microscope at 3 days postbombardment. (A) Leaves bombarded with pPVX.GFP-Bsp alone, showing infection in a single cell. (B) Leaves bombarded with pPVX.GFP-Bsp plus pRTS6, showing multicellular infection site. Each panel shows three independent cells expressing the product.

pPVX.GUS-Bsp was used for cobombardment with pRTS6 into cells of mature leaves of O. sativa to determine whether the S6-encoded protein complements the cell-to-cell movement of the movement-defective PVX in the natural host of RDV. The movement-competent PVX, pPVXGUS, was used as a control. No blue cells were observed in the rice tissues bombarded with either pPVXGUS alone or a combination of pPVX.GUS-Bsp and pRTS6 by using histochemical staining and light microscopy. However, blue cells were observed when GUS alone was expressed (data not shown). Thus, PVX was not able to establish an infection in rice in the presence of S6, and we were unable to evaluate the ability of the S6-encoded protein to function as a movement protein in this host.

Subcellular location of Pns6-eGFP in leaves of N. tabacum and of Pns6 in leaves of O. sativa.

To determine the subcellular location of RDV Pns6 in epidermal cells, the S6 ORF was fused with the 5′ end of the coding sequence of eGFP and expressed through the activity of an enhanced CaMV 35S promoter (pRTL2S6:eGFP [Fig. 1]). A free eGFP behind the same promoter (Fig. 1) was used as a control. The subcellular locations of the proteins expressed from these plasmids were determined by confocal laser scanning microscopy.

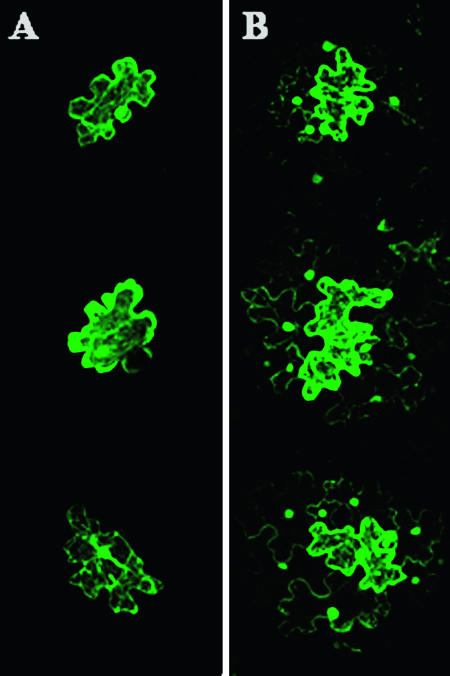

Expression of the Pns6-eGFP fusion yielded strongly fluorescing structures along the cell wall, possibly associated with PD (Fig. 5 and data not shown). Free eGFP did not target to the cell wall or form subcellular aggregates in epidermal cells (data not shown). To determine whether the Pns6-eGFP fusion functioned similarly to native Pns6 in complementing the cell-to-cell movement of the movement-defective PVX, cobombardment with pPVX.GUS-Bsp and pRTL2S6:eGFP was performed. The Pns6-eGFP fusion complemented the cell-to-cell movement of pPVX.GUS-Bsp on N. benthamiana leaves (Fig. 3C; Table 1). Thus, multicellular infection by the movement-incompetent PVX occurred even though the Pns6-eGFP fusion protein did not traffic from cell to cell when bombarded alone (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Transient expression of Pns6-eGFP (pRTL2S6:eGFP) in epidermal cells of N. tabacum leaves. Leaves bombarded with pRTL2S6:eGFP were harvested at 30 h postbombardment, and images were taken with a confocal laser scanning microscope. (A) Fluorescent image of the expression pattern of Pns6-eGFP in a single cell. (B) Bright-field image under Nomarski illumination. (C) Merged image of panels A and B. Panels A and B are single optical sections from the same location within the cell.

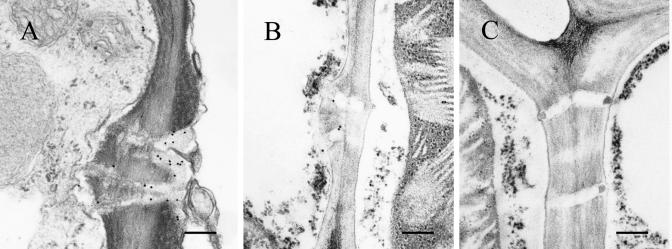

To confirm that RDV Pns6 associated with PD, tissue from RDV-infected leaves of O. sativa was fixed and embedded, and sections were probed with gold-conjugated antibody against Pns6. Branched and simple PDs within RDV-infected rice leaves were labeled (Fig. 6A and B), and PDs from uninfected healthy rice leaf tissues were not labeled (Fig. 6C). These results are consistent with the results from transient expression of the Pns6-eGFP fusion in epidermal cells of tobacco leaves and further strengthen the conclusion that RDV Pns6 is located in PD within the cell wall.

FIG. 6.

Subcellular localization of Pns6 in RDV-infected leaves of O. sativa (rice). Immunogold labeling of ultrathin sections from RDV-infected (A and B) and healthy (C) rice leaves with Pns6-specific antibody is shown. Bar, 250 nm.

DISCUSSION

Unlike the situation for single-stranded RNA viruses and some DNA viruses, proteins necessary for the cell-to-cell movement of phytoreoviruses were not previously identified. By cobombardment with plasmids containing reporter gene-tagged, movement-defective PVX with plasmids containing ORFs from RDV gene segments S1 to S12, we determined that S6 alone complemented the cell-to-cell movement of the movement-defective PVX mutant in N. benthamiana (Fig. 2B and G). Thus, a protein encoded by RDV that supports virus movement has been identified. The complemented cell-to-cell movement of the movement-defective PVX, however, was not as efficient as that observed for the movement-competent PVX in N. benthamiana (Fig. 2A and B). This could be due to (i) a lack of S6 product availability as the PVX mutant spread from the S6-expressing cell, (ii) the S6 product failing to complement a unique function of the 25-kDa protein not associated with movement of PVX, or (iii) the S6 product being only partially active in complementing the movement function of the 25 kDa protein. The first possibility seems the most likely, since the lesion sizes of the complemented movement-defective PVX increased only slowly as determined by visual observation at later times postbombardment (Y. Li, unpublished observation). In addition, Pns6 fused with eGFP did not accumulate in multiple cells when used for bombardment alone (Fig. 5).

The complemented movement of the movement-defective PVX by Pns6 was more similar to that of the wild-type virus in N. tabacum than to that in N. benthamiana (compare Fig. 2A and B with Fig. 2D and E). Since the constructs used for bombardment were identical, this result indicates that host factors important for spread of the viruses differ in these two species. N. benthamiana is particularly susceptible to a wide range of viruses (7, 44). It is possible that the complementation exhibited in N. benthamiana may be due to an inability of N. benthamiana to limit the accumulation and spread of the wild-type virus through a system not involving movement proteins. Further experiments quantifying virus accumulation and spread within the infected tissue will help to clarify this situation.

Although Pns6 fused with eGFP did not move from cell to cell, this fusion protein was as functional as native Pns6 in supporting the cell-to-cell movement of the movement-defective PVX (Fig. 3C and Table 1). This result indicates that the presence of other viral components, such as RNA or other proteins, was necessary for the multicellular spread of the defective PVX. A similar conclusion was reached to explain how the MP of Tomato mosaic virus complemented the movement of a movement-defective Tomato mosaic virus (40). For tobamoviruses, it is known that in addition to the MP, a viral protein(s) (i.e., the 126- and/or 183-kDa protein) involved in the accumulation of the virus within a cell also modulates virus cell-to-cell and systemic movement (10, 19, 24). Thus, it is possible that Pns6 functions in combination with a protein from PVX to allow movement of this virus. These studies indicate the power of transcomplementation experiments using movement-defective virus to identify proteins necessary for virus spread, in contrast to noncomplementation experiments studying the spread of the expressed putative movement proteins or transcomplementation experiments studying the spread of nonviral reporter proteins in the presence of only the putative movement protein.

The movement-defective PVX was altered to contain a frameshift leading to the loss of 72 C-terminal amino acid residues in the 25-kDa protein ORF (28). The ability of Pns6 to allow movement of the defective PVX indicates that this protein complements one of the functions of the 25-kDa protein. The 25-kDa protein was localized in the cell wall as a small punctate structure within or adjacent to PDs (29). Pns6 fused with GFP was also observed localized to the cell wall of N. tabacum cells, and unfused Pns6 was observed localized specifically to the PD of rice cells (Fig. 5 and 6A and B). The 25-kDa protein has ATP/GTPase activity, binds RNA, targets to a specific cellular compartment(s), moves from cell to cell when fused with eGFP, and has a helicase-like domain (14, 29, 48). Since the mutation in the 25-kDa protein ORF would delete a portion of the helicase domain, it is logical that this region may be critical for PVX cell-to-cell movement and that Pns6 complements the helicase activity missing in the mutant protein. Pns6 has no significant sequence similarity to any known plant viral movement proteins but has sequence similarity to yeast ATP-dependent RNA helicases (Li, unpublished results). Pns6 also is known to regulate the accumulation of and symptom severity induced by RDV (2). For Tobacco mosaic virus, it is known that the 126- or 183-kDa protein, which contain identical helicase-like sequences, also regulates virus accumulation and symptom severity (10, 39). Thus, all of these proteins have significant structural and functional similarities, and the 25-, 126-, and 183-kDa proteins have been shown to aid the cell-to-cell movement of their encoding virus. Further work is needed to determine whether Pns6 has helicase activity.

Recently, the 25-kDa protein has been shown to be a suppressor of RNA silencing (45). Although initial studies indicate that Pns6 is not a suppressor of silencing like the 2b, 19-kDa, 25-kDa, and HC-Pro viral proteins (15, 25, 45, 46; Li, unpublished results), further work is necessary to verify this finding. If Pns6 does not have suppressor activity, this would suggest that suppressor activity and virus movement are two different functions of the 25-kDa protein and that Pns6 complements only the movement function of this protein. Separating these activities would be of great interest to those studying virus movement and RNA silencing.

Acknowledgments

We thank D.C. Baulcombe for providing pPVXGUS, N. benthamiana 16c plants, and Agrobacterium containing the 35S-GFP construct; S. Y. Morozov for providing mutant PVX constructs; Shou-Wei Ding for advice on gene silencing; J. Carrington for providing the pRTL2 vector; E. Blancaflor for advice on confocal microscopy; and Stephen Chisholm and Xin Shun Ding for helpful comments on the manuscript. We thank Cuc Ly for preparation of the final figures.

This work was supported by a National Outstanding Youth Grant of China (30125004); Rockefeller Foundation grant award RF93022; Allocation no. 236, National High Tech (863), China (contract no. 2001AA212131); a Natural Science Foundation of China grant to Y.L.; and a National Key Basic Research Program (973), China grant (contract no. G62000016204) to C.H.W.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aaziz, R., S. Dinant, and B. L. Epel. 2001. Plasmodesmata and plant cytoskeleton. Trends Plant Sci. 6:326-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ando, Y., I. Uyeda, K. Murao, and I. Kimura. 1996. Naturally occurring phenotypic variants differing in symptom severity of rice dwarf phytoreovirus. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 62:466-471. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boccardo, G., and R. G. Milne. 1984. Plant reovirus group. In A. F. Morant and B. D. Harrison (ed.), CM/AAB descriptions of plant viruses, no. 294. Commonwealth Mycological Institute and Association of Applied Biologists, Unwin Brothers Ltd., The Gresham Press, Old Woking, England.

- 4.Carrington, J. C., and D. C. Freed. 1990. Cap-independent enhancement of translation by a plant potyvirus 5′ nontranslated region. J. Virol. 64:1590-1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman, S., T. Kavanagh, and D. C. Baulcombe. 1992. Potato virus X as a vector for gene expression in plants. Plant J. 2:549-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng, N. H., C. L. Su, S. A. Carter, and R. S. Nelson. 2000. Vascular invasion routes and systemic accumulation patterns of tobacco mosaic virus in Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant J. 23:349-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christie, S. R., and W. E. Crawford. 1978. Plant virus range of Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Dis. Rep. 62:20-22. [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Block, M., and D. Debrouwer. 1992. In-situ enzyme histochemistry on plastic-embedded plant material. The development of an artifact-free glucuronidase assay. Plant J. 2:261-266. [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Jong, W., and P. Ahlquist. 1992. A hybrid plant RNA virus made by transferring the noncapsid movement protein from a rod-shaped to an icosahedral virus is competent for systemic infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:6808-6812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derrick, P. M., S. A. Carter, and R. S. Nelson. 1997. Mutation of the tobacco mosaic tobamovirus 126- and 183-kDa proteins: effects on phloem-dependent virus accumulation and synthesis of viral proteins. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 10:589-596. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding, B., A. Itaya, and Y. M. Woo. 1999. Plasmodesmata and cell-to-cell communication in plants. Int. Rev. Cytol. 190:251-316. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fedorkin, O. N., A. Merits, J. Lucchesi, A. G. Solovyev, M. Saarma, S. Y. Morozov, and K. Makinen. 2000. Complementation of the movement-deficient mutations in potato virus X: potyvirus coat protein mediates cell-to-cell trafficking of C-terminal truncation but not deletion mutant of potexvirus coat protein. Virology 270:31-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giesman-Cookmeyer, D., S. Silver, A. Vaewhongs, S. A. Lommel, and C. M. Deom. 1995. Tobamovirus and dianthovirus movement proteins are functionally homologous. Virology 213:38-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorbalenya, A. E., E. V. Koonin, A. P. Donchenko, and V. M. Blinov. 1989. Two related superfamilies of putative helicases involved in replication, recombination, repair and expression of DNA and RNA genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:4713-4730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo, H. S., and S. W. Ding. 2002. A viral protein inhibits the long range signaling activity of the gene silencing signal. EMBO J. 21:398-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagiwara, K., J. Higashi, K. Namba, T. Uehara-Ichiki, and T. Omura. 2003. Assembly of single-shelled cores and double-shelled cores virus-like particles after baculovirus expression of major structural proteins P3, P7, and P8 of rice dwarf virus. J. Gen. Virol. 84:981-984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haywood, V., F. Kragler, and W. J. Lucas. 2002. Plasmodesmata: pathways for protein and ribonucleoprotein signaling. Plant Cell 14:S303-S325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinlein, M. 2003. Plasmodesmata: dynamic regulation and role in macromolecular cell-to-cell signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5:543-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirashima, K., and Y. Watanabe. 2001. Tobamovirus replicase coding region is involved in cell-to-cell movement. J. Virol. 75:8831-8836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jefferson, R. A. 1987. Assaying chimeric genes in plants: the GUS gene fusion system. Plant Mol. Rep. 5:387-405. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang, Z. 1996. Ultrastructure of plant pathogenic fungi. China Science and Technology Press, Beijing, China.

- 22.Krishnamurthy, K., R., M. Heppler, R. Mitra, E. Blancaflor, M. Payton, R. S. Nelson, and J. Verchot-Lubicz. 2003. The potato virus X TGBp3 protein associates with the ER network for virus cell-to-cell movement. Virology 309:135-151. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Lasarowitz, S. G., and R. N. Beachy. 1999. Viral movement proteins as probes for intracellular and intercellular trafficking in plants. Plant Cell 11:535-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewandowski, D. J., and W. O. Dawson. 2000. Functions of the 126- and 183-kDa proteins of tobacco mosaic virus. Virology 271:90-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Llave, C., K. D. Kasschau, and J. C. Carrington. 2000. Virus-encoded suppressor of posttranslational gene silencing targets a maintenance step in the silencing pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:13401-13406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lough, T. J., N. E. Netzler, S. J. Emerson, P. Sutherland, F. Carr, D. L. Beck, W. J. Lucas, and L. S. Forster. 2000. Cell-to-cell movement of potexviruses: evidence for a ribonucleoprotein complex involving the coat protein and first triple gene block protein. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13:962-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mao, Z., Y. Li, H. Xu, and Z. L. Chen. 1998. The 42K protein of rice dwarf virus is a post-translational cleavage product of the 46K outer capsid protein. Arch. Virol. 143:1831-1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morozov, S. Y., O. N. Fedorkin, G. Juttner, J. Schiemann, D. C. Baulcombe, and J. G. Atabekov. 1997. Complementation of a potato virus X mutant mediated by bombardment of plant tissues with cloned viral movement protein genes. J. Gen. Virol. 78:2077-2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morozov, S. Y., A. G. Solovyev, N. O. Kalinina, O. N. Fedorkin, O. V. Samuilova, J. Schiemann, and J. G. Atabekov. 1999. Evidence for two nonoverlaping functional domains in the potato virus X 25K movement protein. Virology 260:55-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nejidat, A., F. Cellier, C. A. Holt, and R. Gafny, A. L. Eggenberger, and R. N. Beachy. 1991. Transfer of the movement protein gene between two tobamoviruses: influence on local lesion development. Virology 180:318-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Omura, T., K. Ishikawa, H. Hirano, M. Ugaki, Y. Minobe, T. Tsuchizaki, and H. Kato. 1989. The outer capsid protein of rice dwarf virus is encoded by genome S8. J. Gen. Virol. 70:2759-2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oparka, K. J., C. M. Duckett, D. A. M. Prior, and D. B. Fisher. 1994. Real time imaging of phloem unloading in the root tip of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 6:759-766. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reichel, C., P. Más, and R. N. Beachy. 1999. The role of the ER and cytoskeleton in plant viral trafficking. Trends Plant Sci. 4:458-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Restrepo, M. A., D. D. Freed, and J. C. Carrington. 1990. Nuclear transport of plant potyviral proteins. Plant Cell 2:987-988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts, A. G., and K. J. Oparka. 2003. Plasmodesmata and the control of symplastic transport. Plant Cell Environ. 26:103-124. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts, A. G., S. Santa Cruz, I. M. Roberts, D. A. M. Prior, R. Turgeon. 1997. Phloem unloading in sink leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana: comparison of a fluorescent solute with a fluorescent virus. Plant Cell 9:1381-1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santa Cruz, S., A. G. Roberts, D. A. M. Prior, S. Chapman, and K. J. Oparka. 1998. Efficient cell-to-cell and phloem-mediated transport of potato virus X: the role of virions. Plant Cell 10:495-510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sasaki, N., Y. Fujita, K. Mise, and I. Furusawa,. 2001. Site-specific single amino acid changes to Lys or Arg in the central region of the movement protein of a hybrid bromovirus are required for adaptation to a nonhost. Virology 279:47-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shintaku, M. H., S. A. Carter, Y. Bao, and R. S. Nelson. 1996. Mapping nucleotides in the 126kDa protein gene that control the differential symptoms induced by two strains of tobacco mosaic virus. Virology 221:218-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tamai, A., and T. Meshi. 2001. Tobamoviral movement protein transiently expressed in a single epidermal cell functions beyond multiple plasmodesmata and spreads multicellularly in an infection-coupled manner. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 14:126-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tamai, A., and T. Meshi. 2001. Cell-to-cell movement of potato virus X: the role of p12 and p8 encoded by the second and third open reading frames of the triple gene block. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 14:1158-1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Töpfer, R. V. Matzeit, B. Gronenborn, J. Schell, and H. H. Steinbiss. 1987. A set of plant expression vectors for transcriptional and translational fusions. Nucleic Acids Res. 15:5890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uyeda, I., N. Suda, N. Yamada, H. Kudo, K. Murao, H. Suga, I. Kimura, E. Shikata, Y. Kitagaw, T. Kusno, M. Sugawara, and N. Suzuki. 1994. Nucleotide sequence of rice dwarf phytoreovirus genome segment 2: completion of sequence analysis of rice dwarf virus. Intervirology 37:6-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Dijk, P., F. A. Van der Meer, and P. G. M. Prion. 1987. Accessions of Australian Nicotiana species suitable as indicator hosts in the diagnosis of plant virus diseases. Neth. J. Plant Pathol. 93:73-85. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Voinnet, O., C. Lederer, and D. C. Baulcombe. 2000. A viral movement protein prevents spread of the gene silencing signal in Nicotiana benthamiana. Cell 103:157-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Voinnet, O., S. Rivas, P. Mestre, and D. Baulcombe. 2003. An enhanced transient expression system in plants based on suppression of gene silencing by the p19 protein of tomato bushy stunt virus. Plant J. 33:949-956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu, H., Y. Li, Z. J. Mao, and Z. L. Chen. 1998. Rice dwarf phytoreovirus segment s11 encodes a nucleic acid binding protein. Virology 240:267-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang, Y., B. Ding, D. C. Baulcombe, and J. Verchot. 2000. Cell-to-cell movement of the 25K protein of potato virus X is regulated by three other viral proteins. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13:599-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zambryski, P., and K. Crawford. 2000. Plasmodesmata: gatekeepers for cell-to-cell transport of developmental signals in plants. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 16:393-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zambryski, P. 1995. Plasmodesmata: plant channels for molecules on the move. Science 270:1943-1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang, F., Y. Li, Y. F. Liu, C. C. An, and Z. L. Chen. 1997. Molecular cloning, sequencing, and functional analysis and expression in E. coli of major core protein gene (S3) of rice dwarf virus Chinese isolate. Acta Virol. 141:161-168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zheng, H. H., Y. Li, C. H. Wei, D. H. Wei, Y. P. Shen, Z. L. Chen, and Y. Li. 2000. Assembly of double-shelled, virus-like particles in transgenic rice expressing two major structural proteins of rice dwarf virus. J. Virol. 74:9808-9810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]