Abstract

The cellular and molecular mechanisms of dysfunction and depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes over the course of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection are still incompletely understood, but chronic immune activation is thought to play an important role in disease progression. We studied CD4+ T-cell biology in CD4C/HIV transgenic (Tg) mice, in which Nef expression is sufficient to induce a severe AIDS-like disease including a preferential decrease of CD4+ T cells. We show here that Nef-expressing Tg CD4+ T cells exhibit an activated/memory-like phenotype which appears to be independent of antigenic stimulation, as documented in experiments involving breeding with AD10 TcR Tg mice. In addition, in vivo bromodeoxyuridine incorporation showed that a larger proportion of Tg than non-Tg CD4+ T cells entered the S phase. However, in vitro, Tg CD4+ T cells were found to have a very limited capacity to divide in response to stimulation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 or in allogeneic mixed leukocyte reactions. Interestingly, despite these observations, the deletion of Tg CD4+ T cells had little impact on the development of other AIDS-like organ phenotypes. Thus, the Nef-induced chronic activation of CD4+ T cells may exhaust the T-cell pool and may contribute to the thymic atrophy and the low number of CD4+ T cells observed in these Tg mice.

CD4+ T cells represent one of the major populations targeted by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) (17). Early after the infection of individuals with HIV-1, functional defects of CD4+ T cells (most of them not productively infected at this stage) can be documented. During the progression of the infection to AIDS, a gradual decline of CD4+ T cells is observed; this decline represents the hallmark of the disease and is one of the most clinically relevant parameters.

It has been found that Nef is critically important for virus replication and disease progression in vivo both in HIV-1-infected individuals (14, 33) and in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected macaques (32). Based on numerous observations, Nef appears to play a multifaceted role; it was found to promote high virulence and accelerate viral replication (reviewed in reference 26) and to downregulate cell surface CD4 (47, 61) and major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) (35) molecules, as well as to affect T-cell activation (1, 3, 15, 38, 62), proliferation (12, 36), and cytokine (interleukin-2 [IL-2] and IL-10) production (7, 38, 67). However, numerous controversial findings have been reported. For instance, in some in vitro studies, Nef was found to induce T-cell activation (1, 3, 5, 6, 15, 16, 37, 55, 68), while in others it was reported to inhibit (2, 3, 11, 13, 20, 30, 38, 45, 46) T-cell activation. Such conflicting results suggest that the function of Nef, particularly in vitro, may be difficult to fully appreciate.

To further study the role of Nef in CD4+ T-cell biology in vivo, we used a murine model of AIDS, CD4C/HIV transgenic (Tg) mice (22, 23). These Tg mice develop a severe AIDS-like disease, characterized by premature death, wasting, and pathological damage to the kidney (interstitial nephritis and segmental glomerulosclerosis), lung (lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis), and heart (myocytolysis and myocarditis) (22, 23, 31, 49). This syndrome occurs without viral replication and is strikingly similar to that observed in AIDS patients, especially pediatric AIDS patients. Previous characterization of these Tg mice also revealed downregulation of cell surface CD4, a loss of thymocytes, and low numbers of peripheral CD4+ T cells but an increase of B cells and their activation (23, 49). It was also demonstrated that Tg CD4+ T cells fail to upregulate cell surface CD40 ligand (CD40L) upon in vitro stimulation (49), a phenotype likely to contribute to the failure to generate germinal centers following immunization with ovalbumin (49).

We used CD4C/HIVNef Tg mice, which express a single HIV-1 gene, nef, to study the effect of Nef on peripheral Tg CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, since CD4+ T-cell loss and defects are generally considered to account for several of the clinical manifestations of AIDS and to affect prognosis (17), we examined whether Nef-expressing CD4+ T cells are required for the development and progression of the other AIDS-like organ phenotypes observed in these Tg mice. The present results provide evidence that the expression of Nef alone has a significant impact on CD4+ T-cell division and functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

CD4C/HIVNef (previously designated CD4C/HIVMutG) mice, expressing only the nef gene of HIV-1, and CD4C/HIVMutA Tg mice, expressing only the rev, env, and nef genes of HIV-1, have been described previously (23). The CD4C/HIVNef Tg mice and their non-Tg littermate controls were used when they were between 6 and 12 weeks of age. The BALB/c mice used to generate the mixed leukocyte reactions (MLR) were 6 to 8 weeks old and were purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley Inc. The AD10 TcR Tg mice (H-2k) (Vα11 and Vβ3 specific for pigeon and moth cytochrome c presented by 1-Ek) were provided by Patrice Hugo and were backcrossed with CD4C/HIVNef Tg mice which had been bred on the B10.BR background for at least seven generations and which were found to be negative for mouse mammary tumor virus types 1 and 6 by genotyping. The CD4-deficient mice were previously described (50) and were originally on a C57BL/6 background. These CD4-deficient mice were backcrossed with CD4C/HIVMutA Tg mice to generate double-mutant mice. Only littermates were compared. All mice used for this work were kept under specific-pathogen-free conditions as described previously (59), and all experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee.

Antibodies and reagents.

The hybridomas producing rat anti-mouse B220 (RA36B2), MHC-II (M5-114), CD8α (53-6.72), and hamster anti-mouse CD3ɛ (145-2C11) monoclonal antibodies (MAb) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, Md.). The hybridoma for hamster anti-mouse CD28 (37.51) was a gift from P. Hugo. The anti-CD3 MAb was purified by using protein G affinity columns. The rabbit anti-Nef polyclonal antibodies were generated as described previously (24). The fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)- and phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled MAb, including anti-CD69, CD44, CD45RB, CD8, B220, hamster immunoglobulin G (IgG), TcRαβ, TcRγδ, CD25, CD62L, and 7-amino-actinomycin (7-AAD), were from Cedarlane. The anti-goat IgG-FITC and anti-mouse IgG-PE were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc. and from Dimension Laboratories Inc., respectively. Irrelevant rat IgG1, rat IgG2a, rat IgG2b, and Armenian hamster IgG1 were used as isotype controls. A Cytofix/Cytoperm Plus kit, a bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU)-FITC flow kit, anti-Vα11 FITC (RR8-1), anti-Vβ3 biotin (KJ25), streptavidin allophycocyanin (APC), and anti-CD4 APC were purchased from BD Pharmingen. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), ionomycin, DNase, and propidium iodide were from Sigma.

Purification of CD4+ T cells.

We used two procedures based on negative selection to purify CD4+ T cells from peripheral (axillary, inguinal, cervical, and brachial) lymph nodes (LNs): depletion by using MAb followed by sheep anti-rat immunoglobulin-coated magnetic beads (Dynabeads, Dynal, Oslo, Norway) and cell sorting with a MoFlo cell sorter (Cytomation Inc.). Purification with magnetic beads was performed by preincubation of cells with a cocktail of rat anti-B220 (RA36B2), rat anti-MHC-II (M5-114), and rat anti-CD8 (53-6.72) MAb followed by depletion with sheep anti-rat-coated magnetic beads, as previously described (24). The purity of the CD4+ TcRαβ+/CD8− T cells was >92% for non-Tg mice and ∼78% for Tg mice as determined by flow cytometry (FACScan/FACS Calibur; Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.).

To obtain purer Tg CD4+ T-cell preparations, cell sorting was used. LN cells were resuspended for 20 min in blocking buffer (phosphate-buffered saline and 20% fetal bovine serum [Gibco/BRL Life Technologies] without sodium azide). Staining was performed with PE-coupled anti-MHC-II, anti-CD8, anti-B220, and anti-TcRγδ on ice for 40 min. The CD4+ T cells were sorted by gating on the PE-negative population. The purity of CD4+ TCRαβ+ cells was 98% in non-Tg mice and 93% in Tg mice, as determined by flow cytometry.

Western blotting.

Western immunoblotting for the detection of Nef and of tyrosine phosphorylated proteins was performed as previously described (23, 24).

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR.

The reverse transcription (RT)-PCR assays were performed as follows. For RT, total RNA isolated from ∼200,000 cells was used as a template in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing 1× FIRST-strand buffer as described by the manufacturer (Invitrogen) with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase and 1 mmol of pd(N)6 random primers/liter. After incubation at 42°C for 1.5 h, the enzyme was inactivated at 99°C for 5 min and the product was diluted to 100 μl for amplification. Ten microliters was used for quantitative PCR amplification with a Quantitect probe PCR kit (QIAGEN) with a reaction mixture containing 200 nM primers, 100 nM probe, 3 mM MgCl2, 800 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1.25 U of Immolase polymerase (Bioline), and 50 mM ROX dye passive control. Quantitative PCR was performed with an MX4000 multiplex quantitative PCR instrument (Stratagene). Amplification was performed with a reaction volume of 50 μl for 40 cycles (30 s at 95°C, 1 min at 60°C). The primers and fluorescent probes used were specific for a 150- to 300-bp amplicon of fully spliced HIV-1 transcripts and a 100-bp amplicon of the S16 as internal standard. Primers and probes were designed and synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., as follows: for HIV (strain NL4-3), for1 (CGC GCA CGG CAA GA), rev1 (GAT CGT CCC AGA TAA GTG CTA AGG), and probe 1/56-FAM-ACC CGA CAG GCC CGA AGG AAT AGA AGA-3BHQ-1; for S16, for (CTT CTG GGC AAG GAG CGA TTT), rev (GAC TGT CGG ATG GCA TAA ATT TGG), and probe 5HEX-CCA CCA CCC TTC ACA CGG ACC CGA-3BHQ-1. The specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility of the quantitative PCR assays were verified by using cDNA prepared from the thymuses of Tg mice expressing HIV-1 (23).

CFSE fluorescent-dye cell labeling and division assay.

CFSE (5- and 6-carboxy-fluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester) (Molecular Probes Inc.) labeling was performed as previously described (24). Anti-CD3 (5 μg/ml) coated onto plastic dishes, soluble anti-CD28, recombinant mouse IL-2 (100 U/ml; Roche Diagnostics GmbH), PMA (5 ng/ml), and ionomycin (250 ng/ml) were used to stimulate CD4+ T cells. Unstimulated cells were used as a fluorescence baseline control. CSFE-labeled cells were analyzed by flow cytometry as described below.

Allogeneic MLR.

CD4+ T cells (105) purified from peripheral LNs of CD4C/HIV-1Nef Tg mice or non-Tg littermates were cocultured with 106 irradiated (3,000 rads) BALB/c splenocytes in round-bottom 96-well plates in complete medium (Iscove's modified Dulbecco medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 2-mercaptoethanol, and antibiotics). After 48 h, the cells were labeled for 16 h with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine/well and then harvested onto glass fiber filters. Incorporated radioactivity was measured with a scintillation counter (RackbetaII-LKB).

Measurement of in vivo DNA synthesis by BrdU incorporation.

BrdU (Sigma) (0.8 mg/ml) was added to drinking water daily for 7, 14, or 21 days. The peripheral LNs were then collected, and CD4+ T-cells were purified with Dynabeads. The CD4+ T cells were fixed and permeabilized with reagents from the BrdU flow kit (BD Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To expose incorporated BrdU, the DNA was digested with 30 μg of DNase (Sigma)/well for 1 h at 37°C. After staining with FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody, 20,000 events were acquired by using a FACS Calibur flow cytometer. Data were analyzed with CellQuest software by following the BD protocol.

Flow cytometric analysis.

Immunostaining was performed as described previously (23, 24). FACScan and FACS Calibur flow cytometers and Cellquest software (Becton Dickinson) were used for Flow cytometric analyses.

Statistics.

Statistical analyses (analysis of variance, Sigmastat, and Student's t test) were performed as previously described (24) except that for data presented in Fig. 6, the Student t tests were performed with the Bonferroni correction for multiplicity of tests. For comparison of the distribution of cells in different categories, i.e., cells having reached one, two, three, four, five, or six divisions in the Tg and non-Tg groups, the Pearson chi-square test was used.

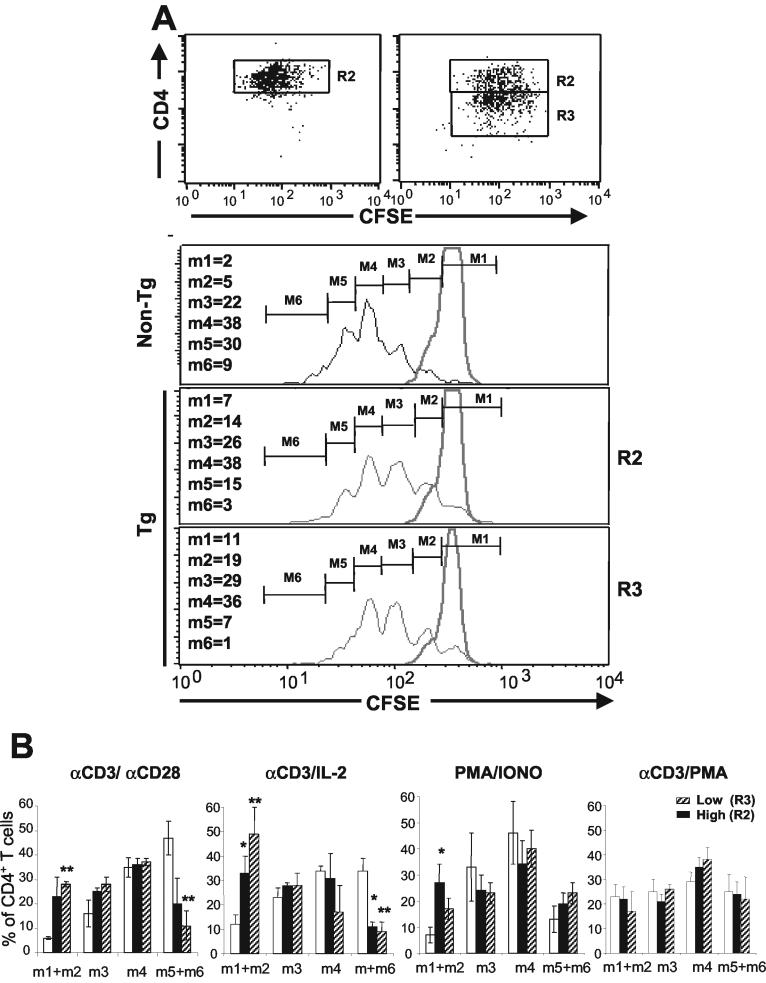

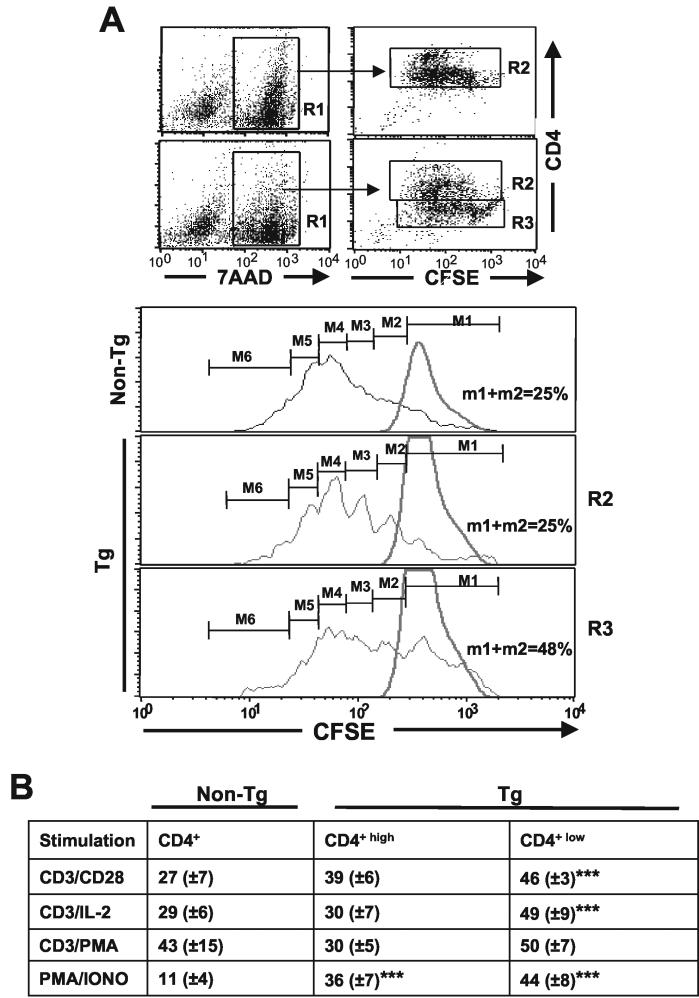

FIG. 6.

Reduced division of CD4+ T cells from CD4C/HIVNef Tg mice in response to in vitro stimulation. Non-Tg and Tg CD4+ T cells were purified from LNs by cell sorting as described in Materials and Methods and labeled with CFSE. After 3 days of culture with various stimuli, the cells were harvested and stained with 7-AAD and CD4 PE. (A) Fluorescence profiles of CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cells. Histograms show the intensity of CFSE fluorescence from 7-AAD-negative CD4+high (R2) or CD4+low (R3) T cells (live cells). Non-Tg and Tg CD4+ T cells were cultured with (black lines) or without (gray lines) anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 for 3 days. The results shown are from one representative experiment of three experiments involving CD4+low and CD4+high T cells and two other experiments involving total CD4+ T cells not separated into two subpopulations. Numbers represent percentages of cells in each division category. (B) Histograms representing the percentages (means ± standard errors of the means) of CD4+ T cells in the indicated generations upon in vitro stimulations for 3 days. The results shown are those for 18 Tg and 15 non-Tg mice. Statistical significance of the distribution of cells in the six division categories for Tg and non-Tg groups was first evaluated by the Pearson chi-square test. It was found that cell distributions during division were not equal (P < 0.001) when the non-Tg group was compared with each of the Tg groups (R2 and R3) in each of the three independent experiments. In addition, pooled data from all experiments (shown in panel B) were analyzed by Student's t test with the Bonferroni correction for multiplicity of tests. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

RESULTS

Low recovery of and Tg expression in purified peripheral CD4+ T cells.

Peripheral CD4+ T-cell numbers were previously found to be preferentially decreased in CD4C/HIV-1 Tg mice, as determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis (22, 23). For the present study, Tg and non-Tg peripheral LN CD4+ T cells were obtained by negative selection by using cell sorting or magnetic beads. A decrease in absolute numbers of recovered Tg CD4+ T cells relative to those of recovered non-Tg CD4+ T cells was observed. As much as a 10-fold reduction in recovered peripheral CD4+ T cells (CD4+, TcRαβ+) was documented in 1.5- to 3-month-old Tg mice from two distinct Nef-expressing lines (CD4C/HIVMutA and CD4C/HIVNef) (9.5 × 106 CD4+ T cells were recovered from 22 non-Tg mice, 1.1 × 106 CD4+ T cells were recovered from 18 CD4C/HIVMutA mice, and 1.5 × 106 CD4+ T cells were recovered from 36 CD4C/HIVNef mice; P < 0.001, Student's t test).

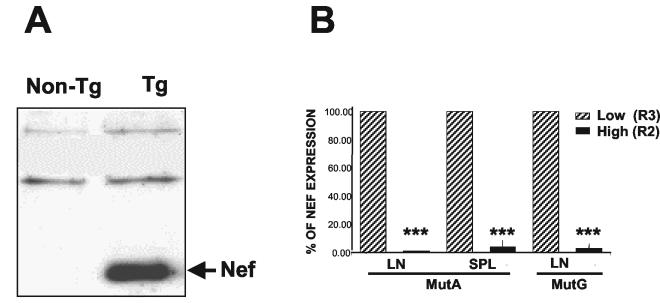

Since Nef is the major determinant of disease in CD4C/HIV Tg mice (23), we assessed the expression of Nef protein in Tg CD4+ T cells. Western blot analysis with anti-Nef polyclonal antibody revealed high levels of expression of Nef in lysates of these cells (Fig. 1A). This result suggests that the low number and some of the anomalies of peripheral CD4+ T cells seen in these mice may be related to the expression of Nef in these cells.

FIG. 1.

Expression of Nef in peripheral CD4+ T cells from CD4C/HIV-1Nef Tg mice. (A) Expression of Nef protein in purified CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cells were purified from LNs by negative selection with Dynabeads as described in Materials and Methods. Total protein extracts (100 μg) from non-Tg and Tg CD4+ T cells were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and analyzed by Western blotting with rabbit anti-Nef antiserum. (B) Expression of transgene HIV RNA in purified CD4+high and CD4+low T cells. Cells were separated into CD4+high (R2) and CD4+low (R3) T-cell populations as described in the legend to Fig. 2A. RNA was extracted from both sorted cell populations and processed for quantitative RT-PCR analysis as described in Materials and Methods. SPL, spleen. Data represent five experiments with 5 non-Tg mice and 19 Tg mice. ***, P < 0.001 (Student's t test).

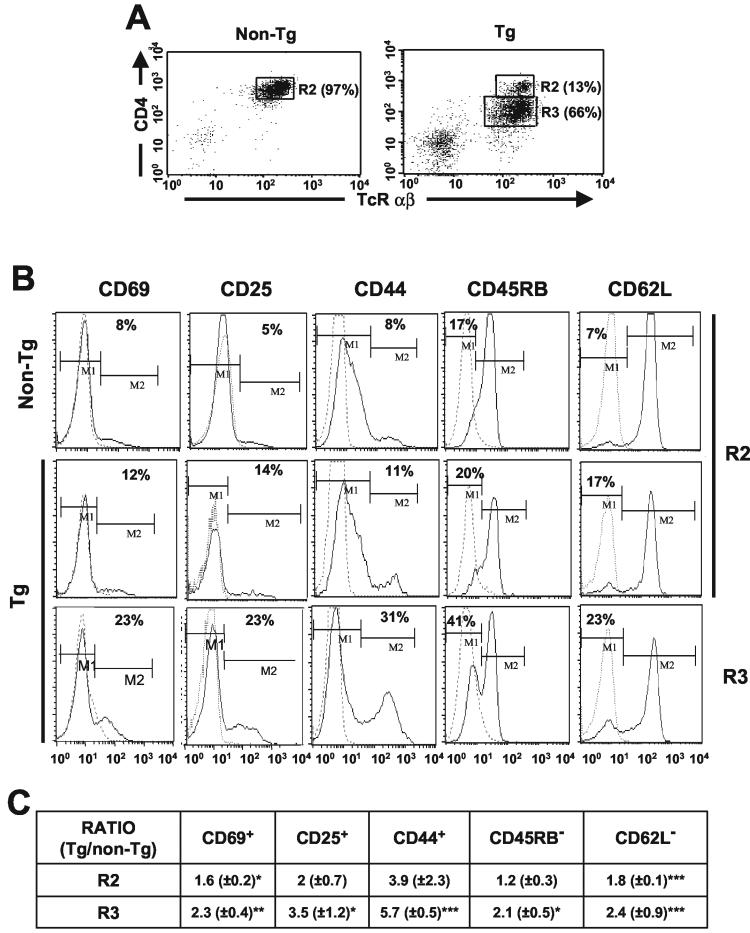

Peripheral Tg CD4+ T cells exhibit an activated/memory-like phenotype.

To determine the cell surface phenotype of the Tg peripheral CD4+ T cells, labeling with different antibodies and FACS analysis were performed with purified LN CD4+ T cells. Often, two subpopulations, CD4+high and CD4+low, were clearly identifiable in Tg mice, while only a CD4+high population was present in non-Tg mice (Fig. 2A). The CD4+low cells expressed higher levels of HIV-1 RNA than the CD4+high cells, as was expected on the basis of the degree of CD4 downregulation (Fig. 1B). Compared to non-Tg controls, Tg CD4+ T cells exhibited an activated/memory-like phenotype; a larger proportion of Tg CD4+ T cells expressed CD69 and CD25 cell surface markers and were CD44high, CD45RBlow, and CD62Llow cells. This phenotype was more pronounced for the CD4+low than for the CD4+high population (Fig. 2B). No change was found for cell surface CD28 and MHC-I expression on CD4+ T cells from Tg mice compared to those from non-Tg littermates (data not shown). Similar results were obtained with cells purified by cell sorting or with magnetic beads and with cells from the CD4C/HIVMutA Tg mice. A summary of these experiments is shown in Fig. 2C.

FIG. 2.

Immunophenotype of purified LN CD4+ T cells from CD4C/HIV-1Nef Tg mice. (A) Two-color FACS analysis of CD4+ TCRαβ+ T cells purified by negative selection with Dynabeads, showing CD4+high (R2) and CD4+low (R3) T-cell populations. (B) Three-color FACS analysis of purified CD4+ T cells. The expression of CD69, CD25, CD44, CD45RB, and CD62L molecules on the surfaces of CD4+ TcRαβ+ T cells expressing high (R2) and low (R3) levels of CD4 is shown for one representative experiment. Isotype control antibodies (dotted lines) were used as negative controls. (C) Table representing ratios (Tg/non-Tg) of the percentages of cells expressing the indicated cell surface markers (M1 for CD62L and CD45RB and M2 for the others), as shown in panel B. Non-Tg values were adjusted to 1 for each experiment. The data were pooled from three experiments with 5 non-Tg mice and 14 CD4C/HIVMutA and CD4C/HIVNef Tg mice. Statistical analysis with the Pearson chi-square test was used to compared the percentages of Tg and non-Tg cells expressing the indicated cell surface markers shown in panels B and C. Groups of non-Tg and Tg CD4high cells were compared, as were groups of non-Tg and Tg CD4low T cells. For each of the three experiments performed, the percentage of Tg CD4+ T cells expressing M2 and M1 was statistically different (P < 0.001) from the percentage of non-Tg CD4+ T cells doing so. In addition, pooled data from the three experiments (shown in panel C) were analyzed by Student's t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

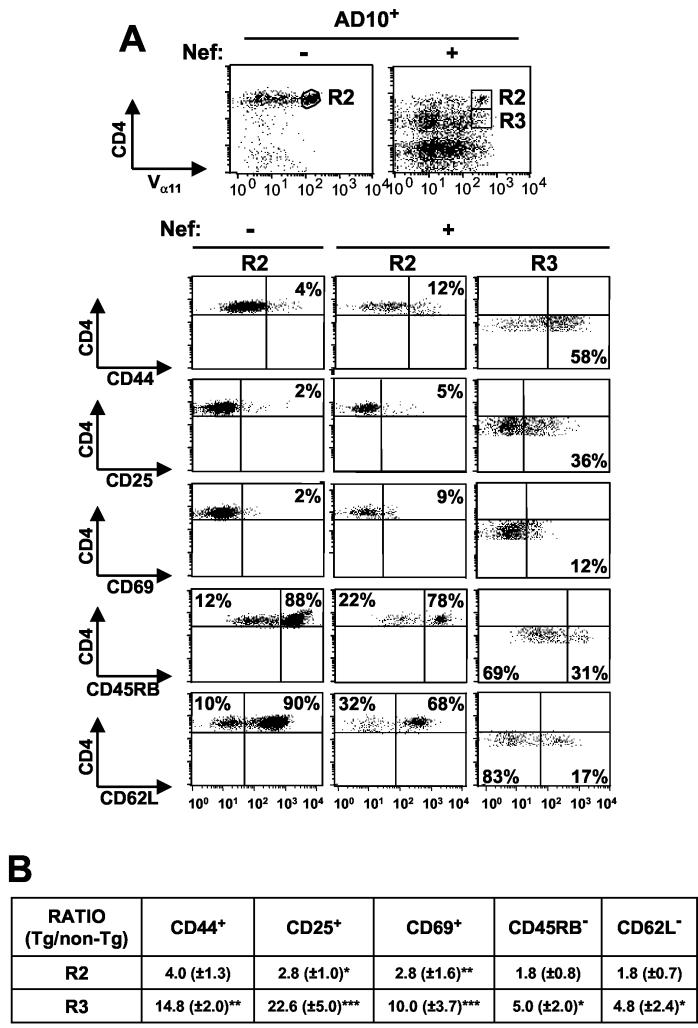

To investigate whether antigenic stimulation (most likely by environmental antigens) through the T-cell receptor (TCR) was required for the appearance of the activated/memory-like phenotype of Tg CD4+ T cells, we bred the CD4C/HIVNef Tg mice with the AD10 TcR Tg mice. The latter Tg mice harbor a TCR transgene (comprising Vα11 and Vβ3 chains) which is expressed at high levels on the majority of peripheral CD4+ T cells and which is specific for pigeon or moth cytochrome c. Since these antigens are not normally present in mice, the vast majority of Vα11Hi and Vβ3Hi cells represent naïve cells. Analysis of LN cells from the CD4C/HIVNef × AD10 double-Tg mice revealed a large relative decrease of Vα11Hi CD4+ T cells and a relative increase of Vα11low/negative CD4+ and Vα11low/negative CD4− T cells compared to the number of cells for AD10 single-Tg mice (Fig. 3A). These Vα11low/negative T cells may express endogenously rearranged TCR chains, and their origin is under investigation (P. Chrobak and P. Jolicoeur, unpublished data). Therefore, in order to exclude such cells, we further analyzed only CD4+ T cells expressing high levels of the TCR transgene. In CD4/HIVNef × AD10 double-Tg mice, activation markers (CD44, CD69, and CD25) were expressed on a higher proportion of Vα11Hi CD4+ T cells of the LNs (Fig. 3) and the spleen (data not shown) compared to AD10 single-Tg controls, thus showing an activated/memory-like phenotype. This phenotype appeared predominantly in CD4+low Tg T cells (Fig. 3A). Importantly, the activated phenotype observed in Vα11Hi CD4+ T cells from double-Tg mice was not decreased compared to that in CD4C/HIVNef single-Tg mice, as might have been anticipated if antigenic stimulation played a role in this phenotype. A summary of these experiments is shown in Fig. 3B). These results suggest that environmental antigenic stimulation may not be required for generating this phenotype.

FIG. 3.

Immunophenotype of LN CD4+ T cells from CD4C/HIVNef × AD10 TcR double-Tg mice. Data shown are for AD10 TcR+ mice harboring (+) or not harboring (−) the HIVNef transgene. (A) The three-color FACS analysis was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 2 except that the CD4+ T cells were identified as Vα11Hi CD4+ cells. Isotype control antibodies were used as negative controls. The dot plots for each stain show the relevant percentages for one representative experiment. (B) Table presenting ratios (Tg/non-Tg) of the percentages of cells of the indicated cell surface phenotype, as represented in panel A. Non-Tg values were adjusted to 1 for each experiment. The data were pooled from three experiments with five non-Tg CD4C/HIVNef mice and five CD4C/HIVMutA Tg mice. R2 and R3, CD4+ TcRαβ+ T cells expressing, respectively, high and low levels of CD4. Statistical analysis with the Pearson chi-square test was used to compare the percentages of cells expressing the indicated cell surface markers. Groups of non-Tg and Tg CD4high cells were compared, as were groups of non-Tg and Tg CD4low T cells. For each of the three experiments performed, the percentage of Tg CD4+ T cells expressing the indicated markers was statistically different (P < 0.001) from the percentage of non-Tg CD4+ T cells doing so. In addition, pooled data from the three experiments (shown in panel B) were analyzed by Student's t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

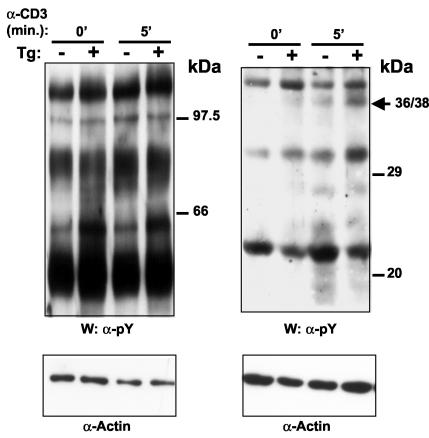

Thymocytes from CD4C/HIVNef Tg mice were previously found to be in a state of activation and to be hyperresponsive to anti-CD3 stimulation, as assessed ex vivo by measurement of their tyrosine phosphorylation pattern (23). To determine whether these features were also found in peripheral CD4+ T cells, Western blot analysis with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody was performed. Constitutively higher levels of tyrosine phosphorylation of several substrates (60, 50, 44/42, 38/36, and 32/30 kDa) were observed in Tg CD4+ T cells than in non-Tg CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4). Following in vitro stimulation with anti-CD3 MAb, enhanced intensity of phosphorylated protein bands of 38/36 and 32/30 kDa could be observed in Tg CD4+ T cells compared to that in control non-Tg cells. Taken together, these results demonstrate that, like the Tg thymocytes, the Tg peripheral CD4+ T cells show features of activation and are hyperresponsive to anti-CD3 stimulation.

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis of tyrosine phosphorylated proteins in LN CD4+ T cells from CD4C/HIV-1Nef Tg mice. Lysates of CD4+ T cells (5 × 105 cells) from non-Tg and Tg mice purified with Dynabeads were prepared after stimulation with anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) for 0 and 5 min (0′ and 5′, respectively). First, Western immunoblotting (W) was performed with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (4G10, anti-pY). The membrane was then washed and reprobed with antiactin as a control for protein loading. The results of loading on two gels of different acrylamide concentrations (6% [left] and 10% [right]) are shown.

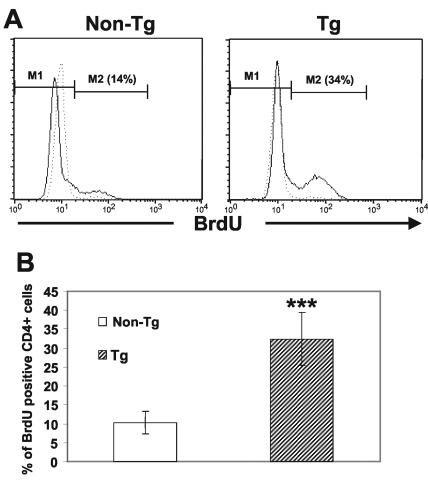

Tg peripheral CD4+ T cells show a higher level of BrdU incorporation in vivo.

To address the question whether the state of activation of the CD4+ T cells was associated with an increase in T-cell proliferation, we assessed cell proliferation in vivo following labeling with BrdU provided in drinking water for 7 (data not shown), 14, or 21 days (Fig. 5). Measurement of cells which had synthesized DNA (BrdU-positive cells) was performed by FACS with purified sorted CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5A). A summary of the results from four experiments is shown in Fig. 5B. The proportion of BrdU-positive Tg CD4+ T cells was found to be increased approximately threefold compared to that of non-Tg CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5B), indicating a higher proportion of Tg CD4+ T cells initiating DNA synthesis. In addition, a higher proportion of Tg CD4+ T cells than of non-Tg CD4+ Tg cells was found to be in the S phase by measurement of the cell cycle by propidium iodide staining of the total DNA content (data not shown). Together, these results suggest an enhanced in vivo division of peripheral CD4+ T cells expressing Nef.

FIG. 5.

Increased BrdU incorporation by CD4+ T cells from CD4C/HIVNef Tg mice. (A) Tg and non-Tg mice were given BrdU in drinking water for 14 days. After this labeling period, LN CD4+ T cells were purified by cell sorting and processed for intracellular staining with anti-BrdU FITC antibody and analyzed by FACS after gating on FSChigh cells (live before fixation). (B) Histogram representing quantitation of live BrdU-positive CD4+ T cells in the S phase. Data similar to those shown in panel A were pooled for 10 Tg and 10 non-Tg mice in four distinct experiments involving BrdU labeling for 14 or 21 days. Statistical analysis was performed by Student's t test. ***, P < 0.0001.

Tg peripheral CD4+ T cells show reduced cell division capacity upon stimulation in vitro.

To determine the proliferative capacity of Tg CD4+ T cells in vitro, sorted CD4+ T cells were labeled with CFSE and analyzed by FACS following different stimulations. This analysis showed that upon in vitro stimulation with a combination of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 MAb, the majority of non-Tg CD4+ and Tg CD4+high T cells divided three to five times (M4 to M6) over a 3-day period, while most Tg CD4+low T cells underwent fewer (two to four) divisions (M3 to M5) (Fig. 6A). The percentage of Tg CD4+low T cells which underwent four divisions or more (M5 and M6) (8%) was lower than that of the non-Tg CD4+ T cells that did (39%). In addition, significant populations of live (7-AAD-negative) Tg CD4+high (21%) and Tg CD4+low (∼30%) T cells did not divide at all (M1) or underwent only one division (M2), whereas such cells were rare (7%) in non-Tg mice. A summary of several experiments is shown in Fig. 6B. Very similar results were obtained with CD4+ T cells purified with magnetic beads (data not shown).

A similar lower rate of division of Tg CD4+low T cells was also obtained by stimulating the cells with anti-CD3 MAb plus IL-2 (Fig. 6B), indicating that IL-2 could not rescue this phenotype. After stimulation with PMA plus ionomycin, a population of Tg CD4+ Tg cells still failed to proliferate, but most of these cells proliferated as well as non-Tg CD4+ T cells (Fig. 6B). However, after stimulation with anti-CD3 MAb plus PMA, comparable proliferation of Tg and non-Tg CD4+ T cells was observed (Fig. 6B). These results suggest that PMA may bypass the inhibitory effect of Nef on cell division.

Therefore, in response to various stimuli, the peripheral Tg CD4+ T cells present in vitro cell autonomous alteration(s) of TcR signaling or distal to it but proximal to the PMA pathway, which cannot be overcome completely by IL-2. The fact that the more severe phenotype is observed in Tg CD4+low T cells, which express higher levels of Nef, suggests that this phenotype correlates with the level of Nef expression.

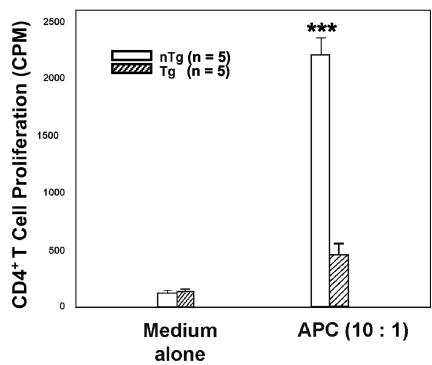

Hyporesponsiveness of peripheral Tg CD4+ T cells in allogeneic MLR.

The response of Tg CD4+ T cells to in vitro stimulation was assessed with an additional functional assay, the MLR assay. Irradiated total splenocytes from normal BALB/c (H-2d) mice were used as stimulators to induce the proliferation of purified allogeneic CD4+ T cells from Tg and non-Tg C3H (H-2k) mice. Tg CD4+ T cells were found to be impaired in their proliferative capacity to respond to an allogeneic MHC stimulation (Fig. 7), again suggesting a functional alteration of these cells. Similar results were obtained with CD4+ T cells purified by cell sorting or with Dynabeads.

FIG. 7.

CD4C/HIV-1Nef Tg CD4+ T cells are unresponsive in an allogeneic MLR. Purified CD4+ T cells (105 cells/well) from peripheral LNs of Tg mice or non-Tg (nTg) littermates were cocultured with irradiated total splenocytes (106 cells/well) from normal BALB/c mice for 48 h. Proliferation was assessed by the incorporation of [3H]thymidine for the final 16 h followed by scintillation counting. ***, P < 0.001 (as estimated by analysis of variance).

The increased cell death following in vitro stimulation of peripheral Tg CD4+ T cells occurs after limited cell divisions.

Given that the Tg CD4+ T cells show limited cell division after in vitro stimulation, we investigated whether this phenotype was associated with enhanced cell death. Non-Tg and Tg sorted CD4+ T cells (>95% 7-AAD negative at time zero) were labeled with CFSE and stimulated with a combination of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 MAb for 3 days. Apoptotic or dead cells (gated on the 7-AAD-positive population) were analyzed for their CFSE patterns. A high proportion (30 to 49%) of Tg CD4+low T cells were found to undergo apoptosis or death after very limited cell division (zero or one division; M1 and M2), while most non-Tg CD4+ T cells and Tg CD4+high cells died after three to five divisions (M4 to M6) (Fig. 8A and B). Similar results were obtained after other stimulations with anti-CD3 plus IL-2 and PMA plus Iono (Fig. 8B). However, no significant difference was observed between CD4+ T cells from non-Tg mice and those from Tg mice after stimulation with anti-CD3 plus PMA (Fig. 8B). Therefore, these results demonstrate that, in vitro, the Tg CD4+ T cells have a significantly compromised cell division capacity that is associated with cell death.

FIG. 8.

Proliferation history of dead CD4+ T cells from CD4C/HIVNef Tg mice. Sorted CD4+ T cells (CD4+ TCRαβ+) (>95% 7-AAD-negative at time zero) from LNs of Tg and non-Tg littermates were labeled with CFSE and stimulated in vitro for 3 days with various mitogens. (A) Stimulation with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28. The CFSE profiles of dead 7-AAD-positive (R1), CD4+low (R3), and CD4+high (R2) T cells from nine Tg mice and four non-Tg mice from one representative experiment are shown. (B) Quantitation of percentages of dead (7-AAD-positive) CD4+ T cells which did not divide (M1) or divided only once (M2) in vitro before dying (M1 + M2) after different stimulations. Data were obtained from CSFE profiles as shown in panel A. Results are presented for both Tg CD4+low and CD4+high T cells and for non-Tg CD4+ T cells. The table represents results from five experiments for Tg CD4+low T cells (18 Tg and 7 non-Tg mice) and from three experiments for Tg CD4+high T cells (9 Tg and 4 non-Tg mice). Non-Tg CD4+ and Tg CD4+high cells were compared, as were non-Tg CD4+ and Tg CD4+low cells. ***, P < 0.001 (Student's t test).

CD4+ T cells are dispensable for the development of the AIDS-like organ disease in CD4C/HIV Tg mice.

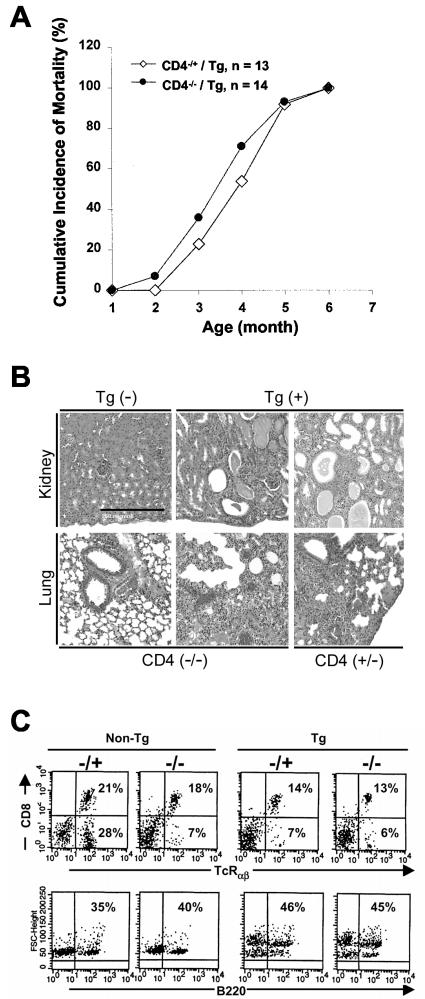

In an attempt to clarify whether or not the defects of peripheral Tg CD4+ T cells contribute to the development of the other phenotypes related to AIDS observed in the CD4C/HIV Tg mice, we used a genetic approach to delete the CD4+ T-cell population from these mice. The CD4C/HIVMutA Tg mice were used for these experiments. These mice express only the rev, env, and nef genes of HIV-1 and exhibit pathological changes indistinguishable from those of CD4C/HIVNef Tg mice (23). These CD4C/HIVMutA Tg mice were backcrossed in a CD4 gene-deficient (CD4−/−) background. CD4−/− mice have been reported to produce no peripheral CD4+ T cells while having normal development of CD8+ T cells and of myeloid cell lineages (50). Groups of CD4−/− CD4C/HIVMutA Tg mice and control CD4+/− CD4C/HIVMutA Tg littermates were generated along with CD4−/− or CD4+/− non-Tg mice. These mice were observed for up to 12 months. No significant difference in mortality rates was found between CD4+/− and CD4−/− CD4/HIVMutA Tg mice (Fig. 9A). Indeed, the CD4−/− CD4C/HIVMutA Tg mice developed severe AIDS-like pathological changes, such as wasting, atrophy of lymphoid tissues, and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis and interstitial nephritis, which were indistinguishable from those observed in the control CD4+/− CD4C/HIVMutA Tg mice (Fig. 9B) or from those reported for CD4+/+ CD4C/HIV Tg mice (22, 23). The non-Tg littermate controls (either CD4−/− or CD4+/−) did not develop any novel pathological lesions during these experiments (data not shown), confirming that the appearance of lesions was transgene-specific. Immunophenotyping of LN cells revealed the same pattern of staining with various MAb (TcRαβ, CD8, and B220) for cells from CD4−/− CD4C/HIV Tg as well as CD4+/− CD4C/HIV Tg mice (Fig. 9C and Table 1).

FIG. 9.

Studies of CD4+ T cells from CD4C/HIVMutA Tg mice bred on a CD4 gene-deficient (CD4−/−) background. (A) The cumulative incidence of death of 14 CD4C/HIVMutA Tg mice homozygous for CD4 gene deletion (CD4−/−) was compared to that of 13 Tg littermates heterozygous for CD4 (CD4+/−). Mice were observed over a period of 12 months. (B) Histopathology of CD4−/− CD4C/HIVMutA Tg mice. Virtually identical lesions were observed for CD4+/− and CD4−/− CD4C/HIVMutA Tg mice. Kidney lesions consisted of tubulardilatation with cystic changes and interstitial nephritis. Lungs exhibited principally lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis. The scale bar in the top left hand panel represents 250 μM and is valid for all images. Counterstain, hematoxylin and eosin stain. (C) Representative FACS profiles of lymphocytes from CD4−/− CD4C/HIVMutA Tg mice. Total cells from mesenteric LNs were analyzed.

TABLE 1.

Immunophenotyping of splenocytes of CD4−/− CD4C/HIVMutA Tg mice

| Tg status | CD4 genotype | No. of animals | % of splenocytes expressing marker (mean ± SD)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ TcR+ | CD8− TcR+ | CD8+ TcR+ | B220 | |||

| Non-Tg | +/− | 5 | 34.3 ± 1.5 | 34.0 ± 5.0 | 24.0 ± 2.0 | 31.7 ± 5.0 |

| −/− | 5 | 0.18 ± 0.12 | 7.2 ± 1.2 | 37.0 ± 17.0 | 39.4 ± 13.0 | |

| Tg | +/− | 6 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 5.7 ± 1.5 | 18.0 ± 2.3 | 56.0 ± 12.0 |

| −/− | 6 | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 6.0 ± 1.1 | 16.0 ± 1.2 | 60.0 ± 14.0 | |

Although the immune compartments of the CD4−/− CD4C/HIVMutA Tg mice remain to be analyzed, our findings indicate that the functionally impaired Tg CD4+ T cells, expressing the HIV gene products, are unexpectedly dispensable for the development and progression of many of the severe AIDS-like organ phenotypes observed in these Tg mice.

DISCUSSION

The CD4+ T cells of CD4C/HIVNef Tg mice present an activated/memory-like phenotype and show enhanced in vivo division.

The present study, which was focused on understanding the impact of Nef on the phenotype and function of peripheral CD4+ T cells in CD4C/HIV Tg mice, revealed a constitutive state of tyrosine hyperphosphorylation which was increased after the engagement of CD3/TcR, indicating an activated molecular phenotype. These results were similar to those obtained previously with thymocytes from these Tg mice (23). In addition, immunophenotyping of these Tg CD4+ T cells showed that a larger proportion of them than of non-Tg cells were CD44high, CD45RBlow, and CD62Llow cells and expressed CD69 and CD25. This activated/memory-like phenotype (63) was more apparent in the Tg CD4+low than in the Tg CD4+high T-cell subpopulations; the Tg CD4+low T cells expressed higher levels of Nef and, as a consequence, showed a more severe downregulation of the CD4 cell surface molecule. Similar enhanced expression of CD44 and lower expression of CD62L on Nef-expressing CD4+ T cells from other Nef Tg mice have been reported (36). Also, some previous reports have shown increased in vitro T-cell activation (16, 40, 60) (enhanced expression of CD69 and CD25 [3] and IL-2 production [52, 54, 55, 67, 70]) in HIV-1 or SIV (1, 15, 37) Nef-expressing CD4+ T cells (reviewed in references 25 and 51). However, other results showed that Nef did not affect CD69 or CD25 expression (9, 30, 54, 56, 67) and was in fact blocking proximal signal required for CD69 expression (30) and inhibiting activation pathways (2, 11, 20, 21) in vitro. These contrasting in vitro results most likely reflect the T cells used for experimentation by different groups and may not be comparable to the data obtained here with the Tg CD4+ T cells.

Consistent with the behavior of the cells in their activated state, we found that the proportion of Tg CD4+ T cells entering the S phase in vivo was also larger than that of non-Tg CD4+ T cells doing so. This finding most likely reflects a higher rate of division rather than slower rate of death, since these peripheral CD4+ T cells also show enhanced apoptosis compared to non-Tg cells, as assessed by labeling with annexin V (E. Priceputu and P. Jolicoeur, unpublished results). This finding represents the first evidence of a stimulatory role of Nef in CD4+ T-cell proliferation in vivo. Evidence for enhanced CD4+ T-cell division in HIV-1-infected individuals has been provided, although not by all groups (27, 28, 41, 69). However, since the above studies did not distinguish between infected and noninfected CD4+ T cells and since the majority of human CD4+ T cells are not infected in vivo, the molecular basis for enhanced cell division of human (largely uninfected) CD4+ T cells and Tg mouse (largely Nef-expressing) CD4+ T cells may not be the same.

It is not clear how Nef is involved in this chronic activation of CD4+ T cells in vivo. Our results with the double-Tg (CD4C/HIVNef × AD10 TcR) mice, which did not present a decrease in the activated phenotype of CD4+ Vα11High T cells, suggest that the upregulation of activation markers might be independent of stimulation by antigens through the TCR. However, the possibility of stimulation by antigens through endogenous TcRαβ rearranged chains cannot be completely excluded, since these mice were not bred on a Rag-deficient background, but appears unlikely. Nef could directly activate the CD4+ T cells in which it is expressed. It has been shown that Nef expression can activate the proximal TCR machinery (25, 51), allowing hyperphosphorylation of effectors such as LAT (23), which has been implicated in T-cell activation (71). On the other hand, the expansion of an activated Tg CD4+ T-cell subset may represent a physiological response to the disease process. Antigen-dependent and -independent activation of T cells undergoing regenerative expansion in lymphopenic hosts has been described (10, 19, 43; for reviews, see references 39 and 64), including in HIV-1 infected individuals (66). In addition, the production of activated/memory-like Tg CD4+ T cells with low CD4 expression may be a consequence of altered thymic maturation; Nef is indeed already expressed at the DP thymocyte stage, and CD4+ SP thymocytes are CD4low and a higher percentage of them than of non-Tg controls express CD25 (P. Chrobak and P. Jolicoeur, unpublished data). However, the downregulation of CD4 is also likely caused by mechanisms other than altered selection, since it is present on TcRneg/low CD4+CD8+ DP thymocytes, which have not undergone selection yet. Finally, the Tg CD4+ T cells with the activated phenotype may even represent a subpopulation of regulatory T cells which often express some activation markers, namely, CD25 (18) (see below).

The induction of such an activated state of the CD4+ T cells, one of the major target cell populations of the virus, may provide an advantage for its replication. Indeed, the expression of the HIV-1 genome in CD4+ T cells has been shown to be dependent on the state of activation of the infected cells, and the integrated proviral DNA is not substantially expressed until cellular activation occurs (8).

The present results with the CD4C/HIV Tg model, which reflects human AIDS for a large number of phenotypes, raise the possibility that Nef may favor the development of a similar activated phenotype of HIV-1-infected human CD4+ T cells in vivo.

Impaired in vitro proliferation of CD4+ T cells from CD4C/HIVNef Tg mice.

In contrast to their enhanced in vivo division, the Tg CD4+ T cells were found to have a very limited proliferative capacity in response to in vitro stimulation. These impaired in vitro responses add to the low helper functions measured previously in the CD4C/HIV Tg mice, which were reflected by low CD40L expression, impaired germinal-center formation, and reduced immunoglobulin isotype class switching (49).

Similar low in vitro proliferation of CD4+ T cells was previously observed with human cells from HIV-1-infected individuals (4, 29, 34, 42, 53, 58). However, a large proportion of these human CD4+ T cells are not infected and their phenotype is influenced by indirect factors; the molecular basis for their phenotype may be distinct from the Nef-induced proliferation defects observed in the CD4C/HIVNef Tg mice. Impaired in vitro proliferative responses, however, have not been reported in most studies with HIV-1- or SIV-infected or Nef-expressing CD4+ T cells, possibly because transformed cell lines or in vitro-infected cultured, stimulated CD4+ T cells obtained from peripheral blood mononuclear cells were used for experimentation. Impaired in vitro proliferative responses were, however, observed in ConA- or SEB-stimulated total spleen or LN cells from other Nef Tg (B6/338L) mice (36) and in Jurkat T cells expressing an inducible SIV Nef (44).

The molecular mechanisms of the in vitro defects of CD4C/HIV Tg CD4+ T cells are likely to be complex. Downregulation of the CD4 molecule on the cell surface is unlikely to be the unique cause of the proliferative defects, since a myristoylation-negative mutant of Nef expressed in Tg mice under the same CD4C regulatory sequences does not induce disease or inhibit T-cell proliferation but nevertheless still induces downregulation of CD4, although this downregulation is less extensive (an ∼30 to 50% decrease of mean fluorescence intensity) than that seen with the wild-type Nef (an ∼60 to 70% decrease) (49) (Z. Hanna, E. Priceputu, D. G. Kay, J. Poudrier, P. Chrobak, and P. Jolicoeur, unpublished data). First, these in vitro proliferation defects may be directly induced by intracellular Nef proteins, since they correlate with the levels of Nef expression. Our data suggest the existence of a major alteration of signal transduction following the engagement of CD3/TcR in these Tg mice. This alteration appears to be at the level of or distal to the TCR itself and upstream of protein kinase C. Second, the in vitro proliferation defects of these CD4+ T cells may reflect their in vivo history in a disturbed environment of enhanced division, which makes them unresponsive to further in vitro stimulation. In fact, a similar phenotype of chronic activation and expansion of effector-memory T cells in vivo with a decreased ability for clonal expansion in vitro has been described in CD70 Tg mice (65). This chronic activation state was found to be associated with the development of a lethal immunodeficiency with losses of thymocytes and of peripheral CD3+ T cells. Similarly, the chronic activation of CD4+ T cells in CD4C/HIV Tg mice may contribute to the thymic atrophy and the very low numbers of peripheral CD4+ T cells previously observed in these Tg mice (22, 23), which has been confirmed here by direct purification techniques. However, our breeding experiments with a CD4-deficient background indicate that these activated Tg CD4+ T cells are not required for the development of several AIDS-like organ phenotypes that were present in the mice. (premature death, wasting, interstitial nephritis and segmental glomerulosclerosis, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis [22, 23], and cardiomyopathy [31]). Finally, the activated phenotype of Tg CD4+ T cells, their reduced expression of CD40L, and their increased production of gamma interferon (49), as well as their hyporesponsiveness in an MLR or after stimulation with MAb engaging the TCR, raise the possibility that a population of professional regulatory/suppressor T cells (57) might be preferentially selected and/or expanded in these CD4C/HIV-1Nef Tg mice. Immature dendritic cells are thought to play an important role in inducing these regulatory suppressor CD4+ T-cell subsets (57). Moreover, dendritic cells from these CD4C/HIV-1 Tg mice were found to have an immature phenotype and to be functionally impaired as disease progresses (48).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to P.J. from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR).

We are grateful to Eve-Lyne Thivierge, Stéphane Gagnon, Ginette Massé, Chunyan Hu, Patrick Couture, and Pascale Jover for excellent technical assistance. We thank Nathalie Tessier, Eric Massicotte, and Martine Dupuis of the Cytofluorometry Core for their support, Claire Crevier of the Histopathology Core Facility for excellent work, and Miguel Chagnon (Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Montreal, Montreal, Canada) for statistical analyses. We are grateful to Rita Gingras for preparing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander, L., Z. Du, M. Rosenzweig, J. U. Jung, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1997. A role for natural simian immunodeficiency virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nef alleles in lymphocyte activation. J. Virol. 71:6094-6099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandres, J. C., and L. Ratner. 1994. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef protein down-regulates transcription factors NF-kappa B and AP-1 in human T cells in vitro after T-cell receptor stimulation. J. Virol. 68:3243-3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baur, A. S., E. T. Sawai, P. Dazin, W. J. Fantl, C. Cheng-Mayer, and B. M. Peterlin. 1994. HIV-1 Nef leads to inhibition or activation of T cells depending on its intracellular localization. Immunity 1:373-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentin, J., C. D. Tsoukas, J. A. McCutchan, S. A. Spector, D. D. Richman, and J. H. Vaughan. 1989. Impairment in T-lymphocyte responses during early infection with the human immunodeficiency virus. J. Clin. Immunol. 9:159-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biggs, T., C. Barton, and D. Mann. 1998. A proposed mechanism for the induction of activator protein 1 (AP-1) binding by HIV-1 negative factor(Nef) in the macrophage cell line RAW267.4 cells. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 26:S263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Briggs, S. D., M. Sharkey, M. Stevenson, and T. E. Smithgall. 1997. SH3-mediated Hck tyrosine kinase activation and fibroblast transformation by the Nef protein of HIV-1. J. Biol. Chem. 272:17899-17902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brigino, E., S. Haraguchi, A. Koutsonikolis, G. J. Cianciolo, U. Owens, R. A. Good, and N. K. Day. 1997. Interleukin 10 is induced by recombinant HIV-1 Nef protein involving the calcium/calmodulin-dependent phosphodiesterase signal transduction pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:3178-3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bukrinsky, M. I., T. L. Stanwick, M. P. Dempsey, and M. Stevenson. 1991. Quiescent T lymphocytes as an inducible virus reservoir in HIV-1 infection. Science 254:423-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carreer, R., H. Groux, J. C. Ameisen, and A. Capron. 1994. Role of HIV-1 Nef expression in activation pathways in CD4+ T cells. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 10:523-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho, B. K., V. P. Rao, Q. Ge, H. N. Eisen, and J. Chen. 2000. Homeostasis-stimulated proliferation drives naive T cells to differentiate directly into memory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 192:549-556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collette, Y., H. Dutartre, A. Benziane, Ramos-Morales, R. Benarous, M. Harris, and D. Olive. 1996. Physical and functional interaction of Nef with Lck. HIV-1 Nef-induced T-cell signaling defects. J. Biol. Chem. 271:6333-6341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooke, S. J., K. Coates, C. H. Barton, T. E. Biggs, S. J. Barrett, A. Cochrane, K. Oliver, J. A. McKeating, M. P. Harris, and D. A. Mann. 1997. Regulated expression vectors demonstrate cell-type-specific sensitivity to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef-induced cytostasis. J. Gen. Virol. 78:381-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De, S. K., and J. W. Marsh. 1994. HIV-1 Nef inhibits a common activation pathway in NIH-3T3 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 269:6656-6660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deacon, N. J., A. Tsykin, A. Solomon, K. Smith, M. Ludford-Menting, D. J. Hooker, D. A. McPhee, A. L. Greenway, A. Ellett, C. Chatfield, et al. 1995. Genomic structure of an attenuated quasi species of HIV-1 from a blood transfusion donor and recipients. Science 270:988-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du, Z., S. M. Lang, V. G. Sasseville, A. A. Lackner, P. O. Ilyinskii, M. D. Daniel, J. U. Jung, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1995. Identification of a nef allele that causes lymphocyte activation and acute disease in macaque monkeys. Cell 82:665-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fackler, O. T., W. Luo, M. Geyer, A. S. Alberts, and B. M. Peterlin. 1999. Activation of Vav by Nef induces cytoskeletal rearrangements and downstream effector functions. Mol. Cell 3:729-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fauci, A. S., G. Pantaleo, S. Stanley, and D. Weissman. 1996. Immunopathogenic mechanisms of HIV infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 124:654-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francois, B. J. 2003. Regulatory T cells under scrutiny. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:189-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldrath, A. W., L. Y. Bogatzki, and M. J. Bevan. 2000. Naive T cells transiently acquire a memory-like phenotype during homeostasis-driven proliferation. J. Exp. Med. 192:557-564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenway, A., A. Azad, and D. McPhee. 1995. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef protein inhibits activation pathways in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and T-cell lines. J. Virol. 69:1842-1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenway, A., A. Azad, J. Mills, and D. McPhee. 1996. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef binds directly to Lck and mitogen-activated protein kinase, inhibiting kinase activity. J. Virol. 70:6701-6708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanna, Z., D. G. Kay, M. Cool, S. Jothy, N. Rebai, and P. Jolicoeur. 1998. Transgenic mice expressing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in immune cells develop a severe AIDS-like disease. J. Virol. 72:121-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanna, Z., D. G. Kay, N. Rebai, A. Guimond, S. Jothy, and P. Jolicoeur. 1998. Nef harbors a major determinant of pathogenicity for an AIDS-like disease induced by HIV-1 in transgenic mice. Cell 95:163-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanna, Z., X. Weng, D. G. Kay, J. Poudrier, C. Lowell, and P. Jolicoeur. 2001. The pathogenicity of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 Nef in CD4C/HIV transgenic mice is abolished by mutation of its SH3-binding domain, and disease development is delayed in the absence of Hck. J. Virol. 75:9378-9392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris, M. 1996. From negative factor to a critical role in virus pathogenesis: the changing fortunes of Nef. J. Gen. Virol. 77:2379-2392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris, M. 1999. HIV: a new role for Nef in the spread of HIV. Curr. Biol. 9:R459-R461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hazenberg, M. D., D. Hamann, H. Schuitemaker, and F. Miedema. 2000. T cell depletion in HIV-1 infection: how CD4+ T cells go out of stock. Nat. Immunol. 1:285-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hellerstein, M. K., and J. M. McCune. 1997. T cell turnover in HIV-1 disease. Immunity 7:583-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hofmann, B., K. D. Jakobsen, N. Odum, E. Dickmeiss, P. Platz, L. P. Ryder, C. Pedersen, L. Mathiesen, I. B. Bygbjerg, and V. Faber. 1989. HIV-induced immunodeficiency. Relatively preserved phytohemagglutinin as opposed to decreased pokeweed mitogen responses may be due to possibly preserved responses via CD2/phytohemagglutinin pathway. J. Immunol. 142:1874-1880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iafrate, A. J., S. Bronson, and J. Skowronski. 1997. Separable functions of Nef disrupt two aspects of T cell receptor machinery: CD4 expression and CD3 signaling. EMBO J. 16:673-684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kay, D. G., P. Yue, Z. Hanna, S. Jothy, E. Tremblay, and P. Jolicoeur. 2002. Cardiac disease in transgenic mice expressing human immunodeficiency virus-1 Nef in cells of the immune system. Am. J. Pathol. 161:321-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kestler, H. W., D. J. Ringler, K. Mori, D. L. Panicali, P. K. Sehgal, M. D. Daniel, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1991. Importance of the nef gene for maintenance of high virus loads and for development of AIDS. Cell 65:651-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirchhoff, F., T. C. Greenough, D. B. Brettler, J. L. Sullivan, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1995. Brief report: absence of intact nef sequences in a long-term survivor with nonprogressive HIV-1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:228-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lane, H. C., J. M. Depper, W. C. Greene, G. Whalen, T. A. Waldmann, and A. S. Fauci. 1985. Qualitative analysis of immune function in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Evidence for a selective defect in soluble antigen recognition. N. Engl. J. Med. 313:79-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Gall, S., J. M. Heard, and O. Schwartz. 1997. Analysis of Nef-induced MHC-I endocytosis. Res. Virol. 148:43-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindemann, D., R. Wilhelm, P. Renard, A. Althage, R. Zinkernagel, and J. Mous. 1994. Severe immunodeficiency associated with a human immunodeficiency virus 1 NEF/3′-long terminal repeat transgene. J. Exp. Med. 179:797-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo, W., and B. M. Peterlin. 1997. Activation of the T-cell receptor signaling pathway by Nef from an aggressive strain of simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 71:9531-9537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luria, S., I. Chambers, and P. Berg. 1991. Expression of the type 1 human immunodeficiency virus Nef protein in T cells prevents antigen receptor-mediated induction of interleukin 2 mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:5326-5330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mackall, C. L., F. T. Hakim, and R. E. Gress. 1997. Restoration of T-cell homeostasis after T-cell depletion. Semin. Immunol. 9:339-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manninen, A., P. Huotari, M. Hiipakka, G. H. Renkema, and K. Saksela. 2001. Activation of NFAT-dependent gene expression by Nef: conservation among divergent Nef alleles, dependence on SH3 binding and membrane association, and cooperation with protein kinase C-θ. J. Virol. 75:3034-3037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCune, J. M. 2001. The dynamics of CD4+ T-cell depletion in HIV disease. Nature 410:974-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miedema, F., A. J. Petit, F. G. Terpstra, J. K. Schattenkerk, F. de Wolf, B. J. Al, M. Roos, J. M. Lange, S. A. Danner, J. Goudsmit, et al. 1988. Immunological abnormalities in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected asymptomatic homosexual men. HIV affects the immune system before CD4+ T helper cell depletion occurs. J. Clin. Investig. 82:1908-1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Min, B., R. McHugh, G. D. Sempowski, C. Mackall, G. Foucras, and W. E. Paul. 2003. Neonates support lymphopenia-induced proliferation. Immunity 18:131-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ndolo, T., N. K. Dhillon, H. Nguyen, M. Guadalupe, M. Mudryj, and S. Dandekar. 2002. Simian immunodeficiency virus Nef protein delays the progression of CD4+ T cells through G1/S phase of the cell cycle. J. Virol. 76:3587-3595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Niederman, T. M., J. V. Garcia, W. R. Hastings, S. Luria, and L. Ratner. 1992. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef protein inhibits NF-kappa B induction in human T cells. J. Virol. 66:6213-6219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Niederman, T. M., W. R. Hastings, S. Luria, J. C. Bandres, and L. Ratner. 1993. HIV-1 Nef protein inhibits the recruitment of AP-1 DNA-binding activity in human T-cells. Virology 194:338-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piguet, V., O. Schwartz, S. Le Gall, and D. Trono. 1999. The downregulation of CD4 and MHC-I by primate lentiviruses: a paradigm for the modulation of cell surface receptors. Immunol. Rev. 168:51-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poudrier, J., X. Weng, D. G. Kay, Z. Hanna, and P. Jolicoeur. 2003. The AIDS-like disease of CD4C/human immunodeficiency virus Tg mice is associated with accumulation of immature CD11bHi dendritic cells. J. Virol. 77:11733-11744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poudrier, J., X. Weng, D. G. Kay, G. Paré, E. L. Calvo, Z. Hanna, M. H. Kosco-Vilbois, and P. Jolicoeur. 2001. The AIDS disease of CD4C/HIV transgenic mice shows impaired germinal centers and autoantibodies and develops in the absence of IFN-γ and IL-6. Immunity 15:173-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rahemtulla, A., W. P. Fung-Leung, M. W. Schilham, T. M. K:undig, S. R. Sambhara, A. Narendran, A. Arabian, A. Wakeham, C. J. Paige, R. M. Zinkernagel, et al. 1991. Normal development and function of CD8+ cells but markedly decreased helper cell activity in mice lacking CD4. Nature 353:180-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Renkema, G. H., and K. Saksela. 2000. Interactions of HIV-1 nef with cellular signal transducing proteins. Front. Biosci. 5:d268-d283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rhee, S. S., and J. W. Marsh. 1994. HIV-1 Nef activity in murine T cells. CD4 modulation and positive enhancement. J. Immunol. 152:5128-5134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roos, M. T., M. Prins, M. Koot, F. de Wolf, M. Bakker, R. A. Coutinho, F. Miedema, and P. T. Schellekens. 1998. Low T-cell responses to CD3 plus CD28 monoclonal antibodies are predictive of development of AIDS. AIDS 12:1745-1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schibeci, S. D., A. O. Clegg, R. A. Biti, K. Sagawa, G. J. Stewart, and P. Williamson. 2000. HIV-Nef enhances interleukin-2 production and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity in a human T cell line. AIDS 14:1701-1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schrager, J. A., and J. W. Marsh. 1999. HIV-1 Nef increases T cell activation in a stimulus-dependent manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:8167-8172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwartz, O., F. Arenzana-Seisdedos, J. M. Heard, and O. Danos. 1992. Activation pathways and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication are not altered in CD4+ T cells expressing the nef protein. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 8:545-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shevach, E. M. 2001. Certified professionals: CD4+CD25+ suppressor T cells. J. Exp. Med. 193:F41-F46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sieg, S. F., C. V. Harding, and M. M. Lederman. 2001. HIV-1 infection impairs cell cycle progression of CD4+ T cells without affecting early activation responses. J. Clin. Investig. 108:757-764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Simard, M.-C., P. Chrobak, D. G. Kay, Z. Hanna, S. Jothy, and P. Jolicoeur. 2002. Expression of simian immunodeficiency virus nef in immune cells of transgenic mice leads to a severe AIDS-like disease. J. Virol. 76:3981-3995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Simmons, A., V. Aluvihare, and A. McMichael. 2001. Nef triggers a transcriptional program in T cells imitating single-signal T cell activation and inducing HIV virulence mediators. Immunity 14:763-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Skowronski, J., M. E. Greenberg, M. Lock, R. Mariani, S. Salghetti, T. Swigut, and A. J. Iafrate. 1999. HIV and SIV Nef modulate signal transduction and protein sorting in T cells. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 64:453-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Skowronski, J., D. Parks, and R. Mariani. 1993. Altered T cell activation and development in transgenic mice expressing the HIV-1 nef gene. EMBO J. 12:703-713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sprent, J., and C. D. Surh. 2002. T cell memory. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20:551-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Surh, C. D., and J. Sprent. 2000. Homeostatic T cell proliferation: how far can T cells be activated to self-ligands? J. Exp. Med. 192:F9-F14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tesselaar, K., R. Arens, G. M. van Schijndel, P. A. Baars, M. A. van der Valk, J. Borst, M. H. van Oers, and R. A. van Lier. 2003. Lethal T cell immunodeficiency induced by chronic costimulation via CD27-CD70 interactions. Nat. Immunol. 4:49-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Walker, R. E., C. S. Carter, L. Muul, V. Natarajan, B. R. Herpin, S. F. Leitman, H. G. Klein, C. A. Mullen, J. A. Metcalf, M. Baseler, J. Falloon, R. T. Davey, J. A. Kovacs, M. A. Polis, H. Masur, R. M. Blaese, and H. C. Lane. 1998. Peripheral expansion of pre-existing mature T cells is an important means of CD4+ T-cell regeneration HIV-infected adults. Nat. Med. 4:852-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang, J. K., E. Kiyokawa, E. Verdin, and D. Trono. 2000. The Nef protein of HIV-1 associates with rafts and primes T cells for activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:394-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Whetter, L., F. J. Novembre, M. Saucier, S. Gummuluru, and S. Dewhurst. 1998. Costimulatory pathways in lymphocyte proliferation induced by the simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsmmPBj14. J. Virol. 72:6155-6158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wolthers, K. C., H. Schuitemaker, and F. Miedema. 1998. Rapid CD4+ T-cell turnover in HIV-1 infection: a paradigm revisited. Immunol. Today 19:44-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu, Y., and J. W. Marsh. 2001. Selective transcription and modulation of resting T cell activity by preintegrated HIV DNA. Science 293:1503-1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang, W., J. Sloan-Lancaster, J. Kitchen, R. P. Trible, and L. E. Samelson. 1998. LAT: the ZAP-70 tyrosine kinase substrate that links T cell receptor to cellular activation. Cell 92:83-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]