Abstract

In allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT), natural killer (NK) cells lacking their cognate inhibitory ligand can induce graft-versus-leukemia responses, without the induction of severe graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). This feature can be exploited for cellular immunotherapy. In this study, we examined selective expansion of NK cell subsets expressing distinct killer immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) within the whole human peripheral blood NK cell population, in the presence of HLA-Cw3 (C1) or Cw4 (C2) transfected K562 stimulator cells. Coculture of KIR+ NK cells with C1 or C2 positive K562 cells, in the presence of IL-2+IL-15, triggered the outgrowth of NK cells that missed their cognate ligand. This resulted in an increased frequency of alloreactive KIR+ NK cells within the whole NK cell population. Also, after preculture with K562 cells lacking their cognate ligand, we observed that this alloreactive NK population revealed higher numbers of CD107+ cells when cocultured with the relevant K562 HLA-C transfected target cells, as compared to coculture with untransfected K562 cells. This enhanced reactivity was confirmed using primary leukemic cells as target. This study demonstrates that HLA class I expression can mediate the skewing of the NK cell repertoire and enrich the population for cells with enhanced alloreactivity towards leukemic target cells. This feature may support future clinical applications of NK cell-based immunotherapy.

Keywords: alloreactivity, cytotoxicity, immunotherapy, KIR, NK cells, stem cell transplantation

Introduction

Reducing the severity of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), while boosting graft-versus-leukemia responses after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (SCT) is one of the major challenges within the field of transplantation today.1,2,3,4 In this respect, natural killer (NK) cells are of interest for use in immunotherapeutic strategies, as they form the first line of defense in mediating immunity against microbial pathogens, and are efficient effectors in eradicating tumor cells without inducing severe GVHD.5,6,7,8

NK cells survey potential target cells for the absence or loss of expression of human leucocyte antigen (HLA) class I classical (HLA-A,B,C) and non-classical (E,G) molecules through killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) and the inhibitory CD94/NKG2A receptor complex.9,10 Overall, HLA class I expression is surveyed by expression of the lectin-like receptor CD94/NKG2A through its recognition of the ubiquitously expressed HLA-E molecule.11 The expression of KIR allows for a more subtle surveillance, as these receptors recognize specific epitopes present on HLA-A, -B, or -C molecules. The receptors KIR2DL1 and KIR2DL2/3 have as their ligands the HLA-C2 group alleles and HLA-C1 group alleles, respectively. Furthermore, HLA-A3 and -A11 are recognized by KIR3DL2, while HLA-Bw4 is recognized by KIR3DL1. HLA-A3 and -A11 are recognized by KIR3DL2, while HLA-Bw4 is recognized by KIR3DL1.12

In allogeneic SCT, anti-leukemic NK cell alloreactivity can be facilitated by allowing mismatches for specific KIR ligands, i.e., HLA-B and/or HLA-C, between donor and recipient. The introduction of certain HLA mismatches has been shown to induce NK cell-mediated graft-versus-leukemia responses, without inducing severe GVHD, and to contribute to decreased relapse, better engraftment and improved overall survival.13,14,15 Other studies show that NK cell alloreactivity can also be triggered by the presence of an inhibitory KIR in the donor's genotype in the absence of the corresponding KIR ligand in the recipient's HLA repertoire.16,17,18 In SCT, the KIR repertoire of NK cells was shown to be important for the induction of alloreactive NK cell responses.19,20,21,22.

In this study, we used an in vitro culture system to investigate whether we could induce the selective expansion of human peripheral blood derived NK cells with enhanced alloreactivity. We cocultured human mature NK cells together with K562 cells transfected with either a single HLA-C1 or C2 gene, and in the presence of cytokines Results demonstrate that the absence of a specific KIR ligand (HLA-C1 or C2) on the K562 cells favored the outgrowth of NK cells expressing the KIR that lacks their cognate KIR ligand, resulting in an increase of alloreactive NK cells, exhibiting improved cytolytic ability. These results may facilitate future clinical applications of NK cell-based immunotherapy, especially within the field of transplantation

Materials and methods

Cell isolation and genotyping

Buffy coats from healthy human donors were purchased from Sanquin Blood Bank, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, upon written informed consent with regard to scientific use according to Dutch law. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by density gradient centrifugation (Lymphoprep; Nycomed Pharma, Roskilde, Denmark). NK cells were negatively selected (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), resulting in a purity of more than 95%. Parallel to the experiments, HLA-C and KIR genotyping were performed on small samples from all buffy coats (Table 1). Genomic DNA was isolated using the QIAamp DNA blood mini kit (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands). A polymerase chain reaction–sequence-specific primers typing protocol as described by Gagne et al.23 (with minor modifications) was used for KIR typing, with the exclusion of pseudo genes (KIR2DP and KIR3DP). A limited HLA-C locus typing was performed as previously described,24 using a polymerase chain reaction–sequence-specific primer protocol solely aimed at discriminating between the polymorphisms located at exon 2 encoded amino acid positions 77 and 80, relevant for KIR recognition. The HLA-C alleles were thus divided into two groups: HLA-C1 (HLA-Cw [Ser77Asn80] alleles with serine at position 77 and asparagine at position 80), and HLA-C2 (HLA-Cw [Asn77Lys80] alleles with asparagine at position 77 and lysine at position 80). Data analysis was focused on NK cell donors having KIR2DL1, 2 and 3 in their KIR repertoire.

Table 1. KIR genotype and HLA-C type of NK cell donors.

| KIR genotype for KIR2DL/S1/2/3a | HLA-Ca | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donorb | 2DL1 | 2DL2 | 2DL3 | 2DS1 | 2DS2 | 2DS3 | C1 | C2 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 10 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 12 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ND | 1 | 1 |

Coding for KIR2DL/S1/2/3 genotype and HLA-C type; 1=present, 0=not present, ND=not able to determine.

The following donors were selected for detailed analysis based on the presence of KIR2DL1/2/3; 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 11, 13 and 14.

Cell lines

Single cell-derived clonal K562 cell lines expressing HLA-C*03:01 (K562-C1posC2neg) and HLA-C*04:03 (K562-C1negC2pos) were used as stimulatory cells during culture and as target cells in functional assays. Briefly, HLA class I-deficient K562 cells were transfected with full-length HLA-C*03:01 cDNA inserted into the EcoRI and HindIII sites of expression vector pcDNA3.1(−) (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and HLA-C*04:03 cDNA ligated into the pEF6/V5-His expression vector (pEF6/V5-His TOPO TA Expression Kit; Invitrogen). The cell lines K562-C*03:01 and K562-C*04:03 showed stable and strong HLA class I expression (>95%) analyzed by flow cytometry using the HLA class I antibody W6/32 (Sigma, Steinheim, Germany). The expression of HLA-C*03:01 and HLA-C*04:03 was confirmed by mRNA profiling (sequencing of HLA-Cw cDNA). As a control, HLA class I-negative K562 cells transfected with empty vector pcDNA3.1 were used (K562 Cneg). For surface protein analysis, we used the monoclonal antibody (mAb) DT9 (a gift from V. Braud), which has been reported to recognize HLA-E and HLA-C but not HLA-A or HLA-B allotypes, MEM-E/06 (Monosam, Uden, The Netherlands), specific for HLA-E, and W6/32 (Sigma), which recognizes HLA class 1, HLA-A, -B, and -C allotypes.

In vitro culture system

Freshly isolated 1×106 NK cells were cocultured with irradiated K562-C1posC2neg, K562-C1negC2pos and K562-Cneg stimulatory cells in a 1∶1 ratio, in the presence of low dose rhIL-2 (10 U/ml; Chiron, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and rhIL-15 (1 ng/ml; BioSource International, Camarillo, CA, USA) in culture medium consisting of RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with pyruvate (0.02 mM), glutamax (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 µg/ml) and 10% human pooled serum, in a 37 °C, 95% humidity, 5% CO2 incubator.

Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-based division analysis

Cell division was studied by CFSE dilution patterns. Freshly isolated NK cells were labeled with 0.1 µM CFSE (Molecular Probe, Eugene, OR, USA), aliquoted in CFSE labeling buffer (phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.02% human pooled serum), for 10 min at room temperature in the dark. The reaction was stopped by addition of equal volumes of cold human pooled serum. Subsequently, cells were washed three times with CFSE labeling buffer and resuspended in culture medium. CFSE-labeled NK cells were cultured as described above and were analyzed using flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Non-CFSE labeled NK cells were phenotypically analyzed on the FC500 (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL, USA) using the following conjugated mAbs: NKAT2-FITC (KIR2DL2/DL3/DS2) and NKB1-PE (KIR3DL1) from BD Bioscience (Breda, The Netherlands) and CD158a, h-PE (KIR2DL1/S1), CD3-PC5, and CD56-PC7 from Beckman Coulter (Woerden, The Netherlands). CFSE-labeled NK cells were analyzed on the Gallios using the following conjugated mAbs: CD16-FITC (Dako, Heverlee, Belgium), CD3-ECD, CD56-APC-A750, CD158b1/b2, j-PC7 (KIR2DL2/DL3/DS2), CD158e1/e2-APC (KIR3DL1/S1), CD158a, h-APC-A700 (KIR2DL1/S1) and CD45-PO (all provided by Beckman Coulter). For 10-color flow cytometry, fluorochrome combinations were balanced to avoid antibody interactions, sterical hindrance and to detect also dimly expressing populations. Before 10-color analyses were performed, all conjugates were titrated and individually tested for sensitivity, resolution and compensation of spectral overlap. Isotype controls were used to define marker settings. Live gating was performed based on forwards scatter vs. side scatter.

Functional analysis

The functional capacity of NK cells was studied by degranulation patterns (CD107a expression) upon target encounter. CD107a is a functional marker for the identification of natural killer cell activity that correlates with NK cell degranulation and target cell lysis.25 NK cells were harvested from culture and viable NK cells were plated in 96-well V-bottom plates in culture medium supplemented with fluorochrome-conjugated anti-CD107a (1∶200; BD Biosciences, Erembodegem, Belgium). Subsequently, non-irradiated K562-C1posC2neg, K562-C1negC2pos, K562 Cneg or Kasumi-1 (HLA-C1 homozygous, acute myeloid leukemia cell line) target cells were added at an E/T ratio of 1∶2 and incubated at 37 °C, 95% humidity, 5% CO2. After 4 h, the degranulation of NK cells was phenotypically analyzed by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0. Results of different conditions were compared using paired Student's t-tests or repeated measures ANOVA analysis with the Tukey multiple comparison test for post-testing. P values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

To study the phenotypical changes and cytolytic response of mature peripheral NK cells when cocultured in the presence of irradiated stimulatory cells lacking a specific KIR ligand, we set up an in vitro culture system using single HLA-C (either C1 or C2) transfected K562 cells. To this end, freshly isolated NK cells were cultured in the presence of low-dose IL-2 and IL-15 together with irradiated K562 stimulator cells transfected with HLA-C1 (K562-C1posC2neg), HLA-C2 (K562-C1negC2pos) or an empty vector (K562 Cneg) in a 1∶1 ratio. Subsequently, NK cells were phenotypically and functionally analyzed. From our mRNA profiling and staining with the DT9 and W6/32 mAb, we concluded that the transfected cells did not express any classical HLA class I molecules, other than the transfected HLA-C1 or HLA-C2 (results not shown); hence, we confined our analysis to KIR2DL1, KIR2DL2, KIR2DL3, KIR2DS1, KIR2DS2 and KIR2DS3. MEM-E/06 staining revealed that HLA-E was expressed on both transfected, as well as untransfected K562 cells, in all cases to a similar level (not shown).

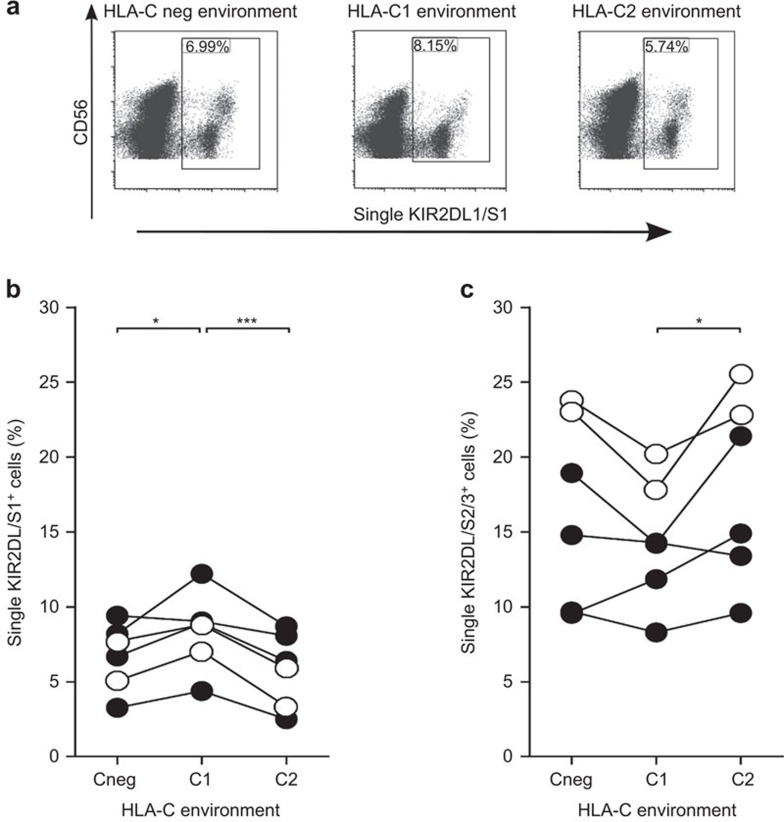

NK cell phenotype is skewed in vitro in the absence of specific KIR ligands

At day 7 of culture, NK cells were phenotypically analyzed for KIR2DL1/S1 and KIR2DL2/DL3/DS2 expression; we focused analysis on NK subsets that were KIR2DL1 and/or KIR2DS1+, but KIR2DL2/DL3/DS2− (single KIR2DL/S1+) or KIR2DL1/S1−, but KIR2DL2+ and/or KIR2DS2+ and/or KIR2DL3+ (single KIR2DL2/DL3/DS2+). As in each donor tested, the percentage of KIR3DL1+ cells never exceeded the 2% (data not shown), precluding meaningful analysis, we omitted this marker from further analysis. CD53+/CD3− NK cells were gated from a live gate on a forward-side scatter dot plot. Single KIR2DL/S1+ and single KIR2DL2/DL3/DS2+ cells were subsequently gated on these NK cells. Skewing of the NK cell phenotype was seen for both KIR subsets (Figure 1). The percentage of single KIR2DL/S1+ NK cells was significantly higher in cultures containing HLA-C1posC2neg stimulatory cells, as compared to cultures containing HLA-C1negC2pos stimulator cells or HLA-C negative stimulator cells (Figure 1b). Visa versa, percentages of single KIR2DL2/DL3/DS2+ NK cells were elevated in the presence of HLA-C1negC2pos stimulatory cells, as compared to cultures containing HLA-C1posC2neg stimulatory cells or, although not in all cases, HLA-C negative stimulator cells (Figure 1c). Thus, in vitro data suggest that an environment in which a specific KIR ligand is absent, leads to a favored NK cell phenotype in which NK cells preferably express the KIR receptor for which the cognate ligand is lacking. Coculture with either C1 or C2 transfected K562 cells did not lead to a difference in the number of cells expressing NKG2A (results not shown).

Figure 1.

Distribution of KIR2DL/S1 and KIR2DL/S2/3 NK cells at day 7 of culture in a nonspecific (HLA-Cneg), HLA-C1posC2neg and HLA-C1negC2pos environment. Freshly isolated NK cells, from donors 6, 7, 9, 11, 13 and 14, were cultured in the presence of irradiated HLA-Cneg, HLA-C1posC2neg and HLA-C1negC2pos K562 stimulatory cells and their phenotype was analyzed at day 7 of culture. (a) Representative dot plots for the cumulative data shown in new b. The open plots (○) in b/c are for heterozygous (C1C2) donors and the closed plots (•) are for donors lacking C2 (C1C1). (b) The percentages of single KIR2DL/S1+ cells within the total NK cell population after nonspecific (HLA-Cneg), HLA-C1posC2neg and HLA-C1negC2pos stimulation at day 7 of culture. Differences between the different stimulation settings were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA analysis; *P<0.05, ***P<0.001. (c) The percentages of single KIR2DL/S2/3+ cells within the total NK cell population after nonspecific (HLA-Cneg), HLA-C1posC2neg and HLA-C1negC2pos stimulation at day 7 of culture. Differences between the different stimulation settings were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA analysis; *P<0.05. HLA, human leucocyte antigen; KIR, immunoglobulin-like receptor; NK, natural killer.

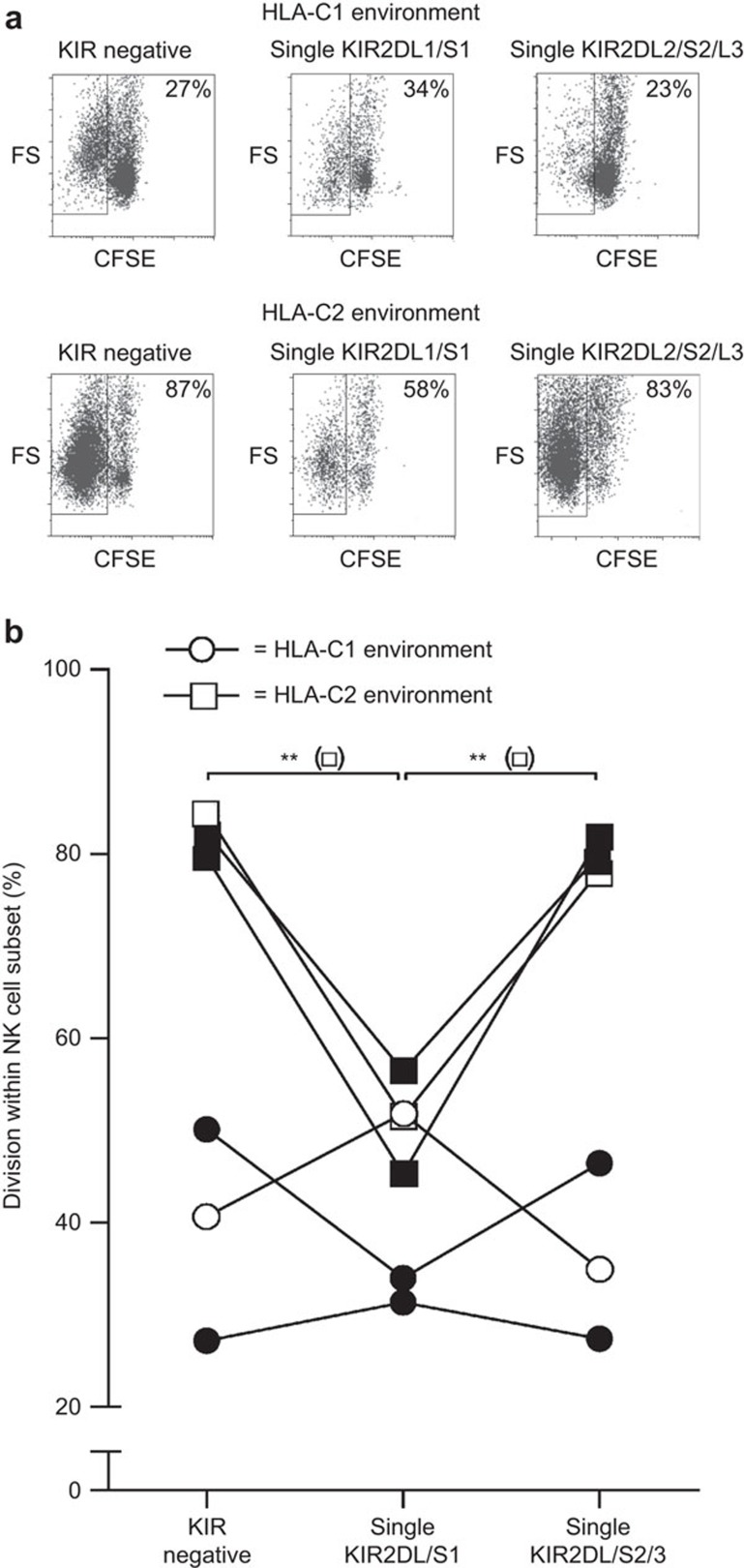

Absence of a specific KIR ligand induces oligoclonal division of specific KIR-positive NK cells

To investigate whether the change in KIR expression pattern, observed upon coculture with transfected K562 cells that lacked the cognate KIR ligand, was due to clonal expansion of specific KIR+ subsets, we performed CFSE-based division analyses. To this end, CFSE-labeled NK cells were cocultured with irradiated stimulator cells lacking a specific KIR ligand. At day 7, the level of cell division of the cultured CFSE-labeled NK cells was analyzed (Figure 2). In the presence of both HLA-C1posC2neg and HLA-C1negC2pos stimulator cells, KIR-negative NK cells were able to divide . However, in the presence of HLA-C1posC2neg stimulator cells, data from two out of three donors showed that single KIR2DL/S1+ NK cells had a higher division rate than single KIR2DL2/DL3/DS2+ NK cells (Figure 2). The opposite effect was seen in the presence of HLA-C1negC2pos stimulatory cells, as single KIR2DL2/DL3/DS2+ NK cells revealed a higher division rate than single KIR2DL/S1+ NK cells (Figure 2b). Thus, KIR+ NK cells that lack their cognate ligand are more prone to expand in culture, as compared to the KIR+ NK cells that are able to recognize their proper ligand in vitro. This suggests that the lack of a KIR ligand guides the proliferation of allospecific KIR+ NK cells.

Figure 2.

Division of single KIR2DL/S1+, single KIR2DL/S2/3+ and KIRneg NK cell subsets at day 7 of culture in an HLA-C1posC2neg and HLA-C1negC2pos environment. CFSE-labeled NK cells, from donors 11, 13 and 14, were cultured in the presence of irradiated HLA-C1posC2neg and HLA-C1negC2pos K562 stimulatory cells and analyzed at day 7 of culture. (a) Representative dot plots for the cumulative data shown in b. The open plots (○/□) in b are for heterozygous (C1C2) donors and the closed plots (•/▪) are for donors lacking C2 (C1C1). (b) The results for three donors of whom NK cells were cultured in an HLA-C1 (○) and an HLA-C2 (□) environment. Depicted are the percentages of divided cells within the KIR negative, single KIR2DL/S1+ and single KIR2DL/S2/3+ NK cell subsets at day 7 of culture. Differences in division between the different NK cell subsets were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA analysis; **P<0.01. HLA, human leucocyte antigen; KIR, immunoglobulin-like receptor; NK, natural killer.

Overall, these results suggest that the introduction of NK cells into an environment, in which a specific KIR ligand is absent, triggers the outgrowth of KIR+ NK cells that lack their cognate KIR ligand, and thus, induces a shift in the overall KIR expression pattern in the whole NK cell population. This shift may well have functional consequences, and thus, we hypothesized that the lack of a specific KIR ligand in vitro may lead to an increase of specific cytolytic KIR+ NK cells within the whole NK cell population.

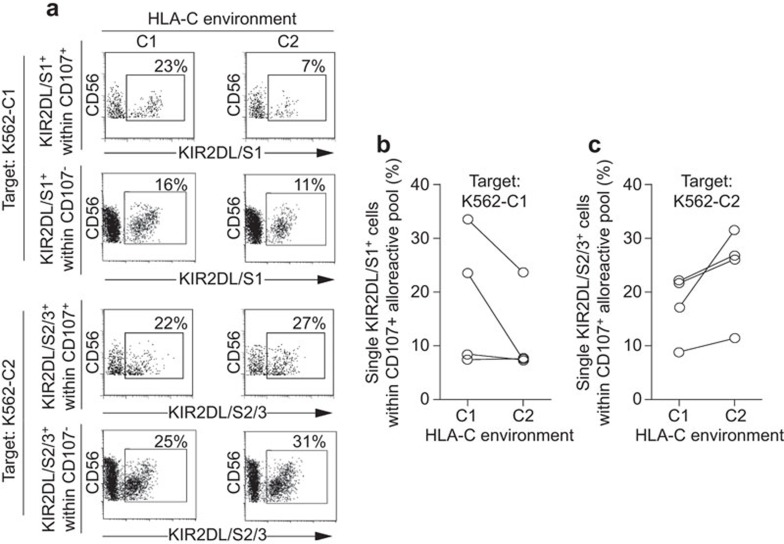

A selective outgrowth of KIR expressing NK cell subsets is associated with increased functional alloreactivity

To investigate whether lack of a specific KIR ligand leads to an increase of specific cytolytic KIR+ NK cells within the whole alloreactive (CD107+) NK cell population, HLA-C1posC2neg and HLA-C1negC2pos stimulated NK cells were analyzed for their degranulation potential against K562-C1posC2neg and K562-C1negC2pos target cells at day 7 of culture (Figure 3). Results showed that stimulation with HLA-C1posC2neg K562 cells led to an increase of cytolytic KIR2DL/S1+ NK cells against K562-C1posC2neg target cells as compared to the percentage of KIR2DL/S1+ NK cells stimulated by HLA-C1negC2pos K562 cells (Figure 3a and b). Vice versa, stimulation of NK cells with HLA-C1negC2pos K562 cells increased the percentage of KIR2DL2/DL3/DS2+ NK cells within the alloreactive CD107+ NK cell pool against K562-C1negC2pos target cells as compared to the percentage of KIR2DL2/DL3/DS2+ NK cells stimulated by HLA-C1posC2neg K562 cells (Figure 3a and c). These results show a clear trend, albeit not significant, that stimulation of NK cells in the absence of a specific KIR ligand may lead to an increase of specific cytolytic KIR+ NK cells within the whole alloreactive NK cell pool against target cells lacking the same KIR ligand. This trend was observed for both NKG2A+ and NKG2A− NK cells as long as they expressed the relevant KIR. As the percentage of the specific cytolytic KIR+ NK cells increased, we further investigated whether this would lead to an enhanced cytolytic alloresponse within a specific alloreactive KIR+ subset.

Figure 3.

Distribution of single KIR2DL/S1+ and single KIR2DL/S2/3+ NK cells within the alloreactive (CD107+) NK cell population upon target encounter. Freshly isolated NK cells, from donors 2, 3, 4 and 5, were cultured in an HLA-C1posC2neg and HLA-C1negC2pos environment and analyzed for degranulation (CD107+) at day 7 of culture against K562-C1posC2neg and K562-C1negC2pos target cells. (a) Representative dot plots for the cumulative data shown in b. The upper two panels depict the percentages of alloreactive (CD107+) and non-alloreactive (CD107a−) single KIR2DL/S1+ NK cells within the whole CD107+ and CD107a− NK cell pool respectively upon K562-C1posC2neg target encounter at day 7 of culture in an HLA-C1posC2neg and HLA-C1negC2pos environment. The lower panels depict the percentages of alloreactive (CD107+) and non-alloreactive (CD107a−) single KIR2DL/S2/3+ NK cells within the whole CD107+ and CD107a− NK cell pool respectively upon K562-C1negC2pos target encounter at day 7 of culture in an HLA-C1posC2neg and HLA-C1negC2pos environment. (b) The percentages of single KIR2DL/S1+ NK cells within the alloreactive (CD107+) NK cell population upon K562-C1posC2neg target encounter at day 7 of culture in an HLA-C1posC2neg and HLA-C1negC2pos environment. Differences between the different stimulation settings were analyzed using paired t-tests. (c) The percentages of single KIR2DL/S2/3+ NK cells within the alloreactive (CD107+) NK cell population upon K562-C1negC2pos target encounter at day 7 of culture in an HLA-C1posC2neg and HLA-C1negC2pos environment. Differences between the different stimulation settings were analyzed using paired t-tests. HLA, human leucocyte antigen; KIR, immunoglobulin-like receptor; NK, natural killer.

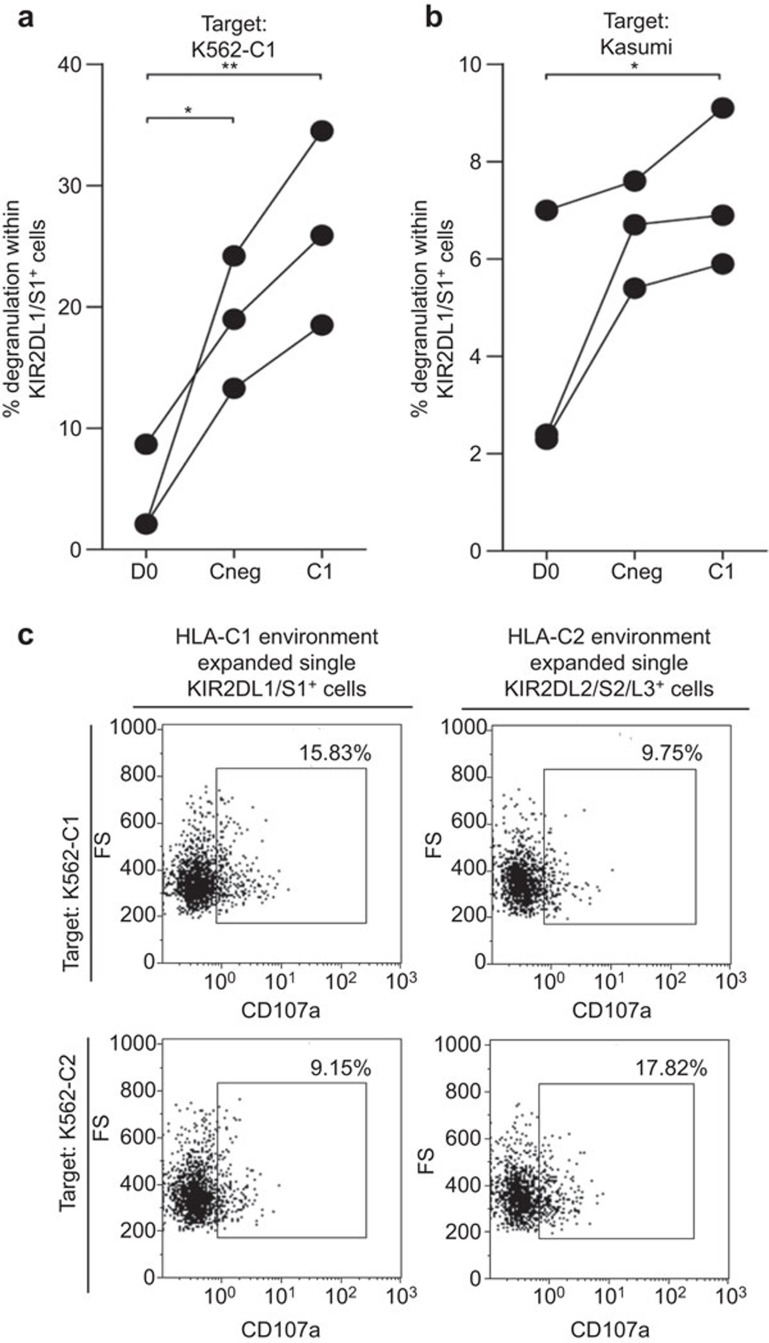

Increased specific cytolytic alloresponse after culture in the absence of a specific KIR ligand

As we were interested to know whether a given alloreactive KIR+ NK cell subset showed enhanced alloreactivity when prestimulated by K562 cells lacking the inhibitory KIR ligand, we tested the degranulation potential of KIR2DL/S1+ NK cells against K562-C1posC2neg target cells after 7 days of prestimulation with HLA-C1posC2neg stimulatory cells (K562-C1posC2neg) and compared this with prestimulation with HLA-negative K562 cells (K562-Cneg) or unstimulated NK cells (D0) (Figure 4a). Stimulating the cells for 7 days with K562-Cneg cells led to an enhanced cytolytic alloresponse (% degranulating cells) of KIR2DL/S1+ NK cells, as compared to freshly isolated NK cells (D0) against K562-C1posC2neg target cells. Thus, stimulation of NK cells by coculture with irradiated HLA-C-negative K562 cells (Cneg) leads to increased alloreactivity. More importantly, stimulation of NK cells in the absence of the specific KIR ligand for KIR2DL/S1+ (C1posC2neg) showed an even stronger cytolytic response of KIR2DL/S1+ NK cells towards K562-C1posC2neg target cells as compared to nonspecifically stimulated NK cells (Cneg).

Figure 4.

Degranulation of single KIR2DL/S1+ NK cells upon target encounter. Freshly isolated NK cells, from donors 6, 7 and 9, were cultured in a nonspecific (HLA-Cneg) and HLA-C1posC2neg environment. NK cells were analyzed for degranulation before culture (D0) and at day 7 of culture upon the encounter of (a) K562-C1posC2neg target cells and (b) the HLA-C1 homozygous primary tumor cell line Kasumi. Differences in degranulation within the single KIR2DL/S1+ NK cell subset before and after culture were analyzed repeated measures ANOVA analysis; *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (c) Inhibition of degranulation of in vitro expanded single KIR2DL1/S1+ and single KIR2DL2/S2/L3+ NK cells from donor 4 when cultured with K562-C2 and K562-C1 target cells, respectively. HLA, human leucocyte antigen; KIR, immunoglobulin-like receptor; NK, natural killer.

As priming of NK cells towards their target is of interest for future NK cell therapies against hematological malignancies or for treatment of solid tumors, we further investigated if stimulation of NK cells in the absence of a specific KIR ligand would trigger the cytolytic KIR+ NK cell subset towards increased killing of a primary tumor cell line. To this end, we tested freshly isolated NK cells before culture (D0) and after 7 days of culture with HLA-negative stimulatory cells (Cneg) and HLA-C1posC2neg stimulatory cells (C1posC2neg) against a primary HLA-C1 homozygous tumor cell line (Kasumi) (Figure 4b). Comparable to the alloreactivity towards K562-C1posC2neg target cells, results show that overall nonspecific stimulation of NK cells within culture (Cneg) led to enhanced alloreactivity of KIR2DL/S1+ NK cells towards the primary HLA-C1 homozygous Kasumi tumor cell line. In addition, the alloreactivity of the KIR2DL/S1+ NK cells was further improved when NK cells were specifically stimulated with HLA-C1posC2neg K562 cells. Thus, in the absence of a specific KIR ligand within the culture system, specific KIR+ NK cells can be primed to give an enhanced cytolytic alloresponse towards non-previously encountered primary tumor cell lines lacking the same KIR ligand.

Discussion

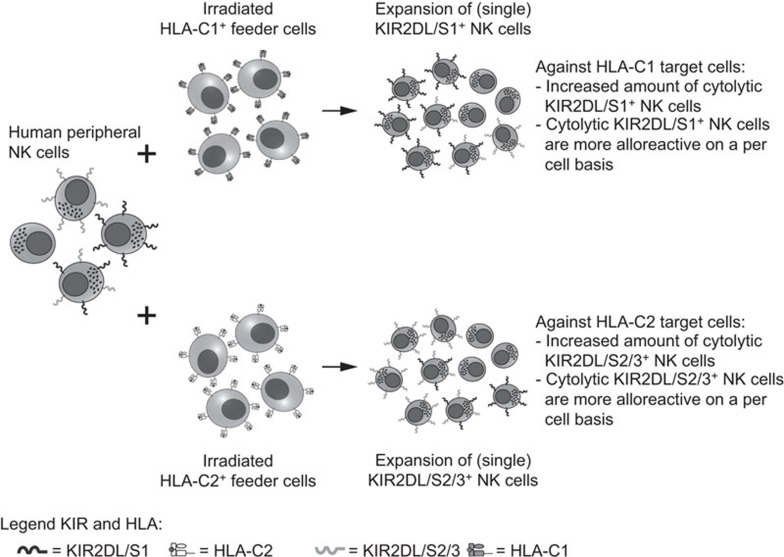

Regulation of cytolytic responses of alloreactive NK cells through interactions between inhibitory KIR and HLA class I ligands has been well described.12 In this study, we show that the phenotype of mature human NK cells from healthy donors can be skewed through stimulation with cells lacking a specific KIR ligand (KIR vs. HLA-C), resulting in an enrichment of specific alloreactive NK cells bearing higher cytolytic responses towards specified targets. A simplified model summarizing our findings is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic in vitro model for the selective expansion of alloreactive NK cells. Here, a human peripheral NK cell population is shown containing KIR-negative, KIR2DL/S1+, KIR2DL/S2/3+ and KIR2DL/S1+/KIR2DL/S2/3+ NK cells. In the presence of irradiated HLA-C1posC2neg stimulator cells (upper scheme), KIR2DL/S1+ NK cells expand in culture leading to an increase in cytolytic KIR2DL/S1+ NK cells within the whole alloreactive NK cell population upon HLA-C1posC2neg target encounter. In addition, these cytolytic KIR2DL/S1+ cells reveal a higher alloreactive capacity, as compared to freshly isolated or nonspecific stimulated KIR2DL/S1+ NK cells. Vice versa, in the presence of irradiated HLA-C1negC2pos stimulator cells (lower scheme), KIR2DL/S2/3+ NK cells expand in culture leading to an increase in cytolytic KIR2DL/S2/3+ NK cells within the whole alloreactive NK cell population upon HLA-C1negC2pos target encounter. In addition, although not analyzed in this study, these cytolytic KIR2DL/S2/3+ cells may be more alloreactive, as compared to freshly isolated or nonspecific stimulated KIR2DL/S2/3+ NK cells. HLA, human leucocyte antigen; KIR, immunoglobulin-like receptor; NK, natural killer.

Previous research by Rose et al.26 showed that the KIR repertoire of human NK cells can be shaped mainly by the HLA class I environment. They showed that when feeder cells were mismatched with NK cells for a specific KIR ligand (HLA mismatch), the frequency of the cognate KIR in the NK cell population would increase as compared to autologous or allogeneic HLA-matched cultures. Our results demonstrate that the NK cell KIR repertoire can be skewed in both HLA-matched, as well as in HLA-mismatched situations, in the presence of a KIR–KIR ligand mismatch. Notably, in our culture set-up, we used purified and freshly isolated NK cells and cultured them directly, without pre-activation, in the presence of low-dose IL-2 and IL-15. This set-up may allow for a more bona fide reaction of mature human NK cells to missing KIR ligands, as compared to the a situation where NK cells have been pre-activated. Remarkably, in our CFSE-based division analyses, the skewing effect obtained through HLA-C1negC2pos stimulation tended to be stronger than HLA-C1posC2neg stimulation, which may be explained by the HLA-C type of the donors. Of the three donors used for these experiments (Table 1; donors 11, 13 and 14), two out of three were HLA-C1 homozygous, whereas only one was HLA-C1/C2 heterozygous. According to the NK cell licensing/education model,27,28,29 KIR2DL/S1+ NK cells of HLA-C1 homozygous donors may be hyporesponsive, as these cells lacked their cognate ligand in vivo. This would result in a damped response within an HLA-C1posC2neg environment. The KIR2DL2/DL3/DS2+ NK cells from these same donors would be properly armed as their ligand, HLA-C1, was present in vivo and thus, these cells may be perfectly able to respond within a HLA-C1negC2pos environment. The KIR2DL/S1+ and KIR2DL2/DL3/DS2+ NK cell subsets from the HLA-C heterozygous donor would have been properly armed and thus able to respond to either HLA-C1posC2neg or HLA-C1negC2pos environments (Figure 2b). Thus, our results suggest that the self-HLA-C background of NK cells may be an important determinant for the strength of their response to missing KIR ligands ex vivo. However, our experimental set-up was not designed to allow for conclusive statements on the effect of the HLA background or indeed the licensing/education of NK cells on KIR responses to their respective ligands.

Concerning adoptive transfer of mature NK cells for immunotherapeutic purposes, the results of this study suggest that the presence of inhibitory KIR on donor NK cells in absence of its cognate ligand in the recipient as well as the HLA background of the donor NK cells could be two key factors that determine the alloreactive NK cell response within the recipient.

During NK cell maturation, the KIR repertoire is predominantly formed by the KIR genotype of the cells and is only mildly influenced by the HLA class I type.30,31 The minor role of HLA class I in shaping the KIR repertoire is also reflected in the setting of allogeneic SCT, as reconstitution of the KIR repertoire mainly reflects that of the donor and not the recipients.19,32 Our in vitro study, however, suggests that the KIR repertoire of human mature NK cells can be reshaped by the absence of the relevant ligands. Moreover, in vitro reshaping of the KIR repertoire of mature NK cell populations, within a specific KIR ligand lacking environment, is likely to increase the cytolytic response of the alloreactive KIR+ NK cells against target cells lacking the cognate ligand. Thus, as the KIR genotype is envisaged to be important in the formation of the basic KIR repertoire during NK cell maturation, the HLA class I environment could be a dominant factor in reshaping the KIR repertoire and determining the strength of the cytolytic NK cell response after NK cell maturation.

Currently, NK cells are already being exploited in the setting of hematological malignancies to induce an antileukemic effect.33 An ex vivo coculture protocol in which NK cell skewing can be induced by the presence of specific KIR ligands (i.e., HLA molecules) can be an augmentation to these protocols to achieve desired KIR-mediated alloreactivity. Obviously, this should be performed under GMP conditions and the relevant HLA molecules should preferably be expressed in a cell-free system.

Overall, these findings hold promise for future transplantation strategies using mature NK cells as effectors, and future research is warranted to optimize and exploit the skewing of NK cell responses towards specific targets for the immunotherapeutic treatment of hematological malignancies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sylvie van der Zeeuw-Hingrez for technical assistance in generating the transfected K562 cell lines. Technical support on the Gallios, and specified conjugated mAbs were kindly provided by Beckman Coulter. Clive M. Michelo is funded by the Dutch kidney foundation.

Authors have no conflicting interests.

References

- Li JM, Giver CR, Lu Y, Hossain MS, Lonial S, Waller EK. Separating graft-versus-leukemia from graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Immunotherapy. 2009;1:599–621. doi: 10.2217/imt.09.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Chen Y, He W, Yi T, Zhao D, Zhang C, et al. Anti-CD3 preconditioning separates GVL from GVHD via modulating host dendritic cell and donor T-cell migration in recipients conditioned with TBI. Blood. 2009;113:953–962. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-165522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das R, Komorowski R, Hessner MJ, Subramanian H, Huettner CS, Cua D, et al. Blockade of interleukin-23 signaling results in targeted protection of the colon and allows for separation of graft-versus-host and graft-versus-leukemia responses. Blood. 2010;115:5249–5258. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-255422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa Y, Li XK, Liu Z, Kimura H, Isaka Y, Hunig T, et al. Prevention of graft-versus-host diseases by in vivo supCD28mAb-expanded antigen-specific nTreg cells. Cell Transplant. 2010;19:765–774. doi: 10.3727/096368910X508870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Urbani E, Perruccio K, Shlomchik WD, Tosti A, et al. Effectiveness of donor natural killer cell alloreactivity in mismatched hematopoietic transplants. Science. 2002;295:2097–2100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook MA, Milligan DW, Fegan CD, Darbyshire PJ, Mahendra P, Craddock CF, et al. The impact of donor KIR and patient HLA-C genotypes on outcome following HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2004;103:1521–1526. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebel S, Nowak I, Wojnar J, Markiewicz M, Dziaczkowska J, Wylezol I, et al. Impact of activating killer immunoglobulin-like receptor genotype on outcome of unrelated donor-hematopoietic cell transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.11.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradier A, Passweg J, Villard J, Kindler V. Human bone marrow stromal cells and skin fibroblasts inhibit natural killer cell proliferation and cytotoxic activity. Cell Transplant. 2011;20:681–691. doi: 10.3727/096368910X536545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papamichail M, Perez SA, Gritzapis AD, Baxevanis CN. Natural killer lymphocytes: biology, development, and function. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:176–186. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0478-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farag SS, Caligiuri MA. Human natural killer cell development and biology. Blood Rev. 2006;20:123–137. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braud VM, Allan DS, O'Callaghan CA, Söderström K, D'Andrea A, Ogg GS, et al. HLA-E binds to natural killer cell receptors CD94/NKG2A, B and C. Nature. 1998;391:795–799. doi: 10.1038/35869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parham P. MHC class I molecules and KIRs in human history, health and survival. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:201–214. doi: 10.1038/nri1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Casucci M, Volpi I, Tosti A, Perruccio K, et al. Role of natural killer cell alloreactivity in HLA-mismatched hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 1999;94:333–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Mancusi A, Urbani E, Carotti A, Aloisi T, et al. Alloreactive natural killer cells in mismatched hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2004;33:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri L, Mancusi A, Capanni M, Urbani E, Carotti A, Aloisi T, et al. Donor natural killer cell allorecognition of missing self in haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia: challenging its predictive value. Blood. 2007;110:433–440. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-038687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung W, Iyengar R, Turner V, Lang P, Bader P, Conn P, et al. Determinants of antileukemia effects of allogeneic NK cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:644–650. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu KC, Keever-Taylor CA, Wilton A, Pinto C, Heller G, Arkun K, et al. Improved outcome in HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia predicted by KIR and HLA genotypes. Blood. 2005;105:4878–4884. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung W, Iyengar R, Triplett B, Turner V, Behm FG, Holladay MS, et al. Comparison of killer Ig-like receptor genotyping and phenotyping for selection of allogeneic blood stem cell donors. J Immunol. 2005;174:6540–6545. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilling HG, McQueen KL, Cheng NW, Shizuru JA, Negrin RS, Parham P. Reconstitution of NK cell receptor repertoire following HLA-matched hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2003;101:3730–3740. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley S, McCullar V, Wangen R, Bergemann TL, Spellman S, Weisdorf DJ, et al. KIR reconstitution is altered by T cells in the graft and correlates with clinical outcomes after unrelated donor transplantation. Blood. 2005;106:4370–4376. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao XY, Huang XJ, Liu KY, Xu LP, Liu DH. Reconstitution of natural killer cell receptor repertoires after unmanipulated HLA-mismatched/haploidentical blood and marrow transplantation: analyses of CD94:NKG2A and killer immunoglobulin-like receptor expression and their associations with clinical outcome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:734–744. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Venstrom JM, Liu XR, Pring J, Hasan RS, O'Reilly RJ, et al. Breaking tolerance to self, circulating natural killer cells expressing inhibitory KIR for non-self HLA exhibit effector function after T cell-depleted allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2009;113:3875–3884. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-177055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagne K, Brizard G, Gueglio B, Milpied N, Herry P, Bonneville F, et al. Relevance of KIR gene polymorphisms in bone marrow transplantation outcome. Hum Immunol. 2002;63:271–280. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(02)00373-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meer A, Schaap NP, Schattenberg AV, van Cranenbroek B, Tijssen HJ, Joosten I. KIR2DS5 is associated with leukemia free survival after HLA identical stem cell transplantation in chronic myeloid leukemia patients. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:3631–3638. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aktas E, Kucuksezer UC, Bilgic S, Erten G, Deniz G. Relationship between CD107a expression and cytotoxic activity. Cell Immunol. 2009;254:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose MJJ, Brooks AG, Stewart LA, Nguyen TH, Schwarer AP. Killer Ig-like receptor ligand mismatch directs NK cell expansion in vitro. . J Immunol. 2009;183:4502–4508. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raulet DH, Vance RE. Self-tolerance of natural killer cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:520–531. doi: 10.1038/nri1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parham P. Taking license with natural killer cell maturation and repertoire development. Immunol Rev. 2006;214:155–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivier E, Tomasello E, Baratin M, Walzer T, Ugolini S. Functions of natural killer cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:503–510. doi: 10.1038/ni1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yawata M, Yawata N, Draghi M, Little AM, Partheniou F, Parham P. Roles for HLA and KIR polymorphisms in natural killer cell repertoire selection and modulation of effector function. J Exp Med. 2006;203:633–645. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson S, Fauriat C, Malmberg JA, Ljunggren HG, Malmberg KJ. KIR acquisition probabilities are independent of self-HLA class I ligands and increase with cellular KIR expression. Blood. 2009;114:95–104. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilling HG, Young N, Guethlein LA, Cheng NW, Gardiner CM, Tyan D, et al. Genetic control of human NK cell repertoire. J Immunol. 2002;169:239–247. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SA, Kim TJ, Lee JE, Sonn CH, Kim K, Kim J, et al. Ex vivo expansion of highly cytotoxic human NK cells by cocultivation with irradiated tumor cells for adoptive immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2598–2607. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]