Abstract

Attenuated Listeria monocytogenes (LM) is a promising candidate vector for the delivery of cancer vaccines. After phagocytosis by antigen-presenting cells, this bacterium stimulates the major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-I and MHC-II pathways and induces the proliferation of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. A new strategy involving genetic modification of the replication-deficient LM strain ΔdalΔdat (Lmdd) to express and secrete human CD24 protein has been developed. CD24 is a hepatic cancer stem cell biomarker that is closely associated with apoptosis, metastasis and recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). After intravenous administration in mice, Lmdd-CD24 was distributed primarily in the spleen and liver and did not cause severe organ injury. Lmdd-CD24 effectively increased the number of interferon (IFN)-γ-producing CD8+ T cells and IFN-γ secretion. Lmdd-CD24 also enhanced the number of IL-4- and IL-10-producing T helper 2 cells. The efficacy of the Lmdd-CD24 vaccine was further investigated against Hepa1–6-CD24 tumors, which were inguinally inoculated into mice. Lmdd-CD24 significantly reduced the tumor size in mice and increased their survival. Notably, a reduction of T regulatory cell (Treg) numbers and an enhancement of specific CD8+ T-cell activity were observed in the tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). These results suggest a potential application of the Lmdd-CD24 vaccine against HCC.

Keywords: cancer stem cell, CD24, hepatocellular carcinoma, immunotherapy, Listeria monocytogenes

Introduction

Cancer and cancer-related diseases are an increasing threat to public health. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which accounts for approximately 85%–90% of primary liver cancers, is the fifth most common type of cancer and the third most common cause of cancer-related death.1 Worldwide, 50% of HCC cases are caused by infection with the hepatitis B virus.2 In China, where hepatitis B virus infection is prevalent, more than 100 persons per million of the Chinese population develop HCC.3 Current therapies for this type of malignancy4 include antiviral strategies, radiotherapy, transarterial chemoembolization and surgery,5,6,7,8 which generally do not result in a good prognosis. Early diagnosis plays a vital role in successful outcomes with these treatments. However, over 80% of HCC patients are diagnosed at advanced stages.9 Because of the high metastasis and recurrence rates of HCC, the long-term survival of HCC patients after liver surgery is unsatisfactory. The postoperative recurrence rate is 65% with radical resection and 58% with liver transplantation.10 Furthermore, the resistance of some HCC patients to conventional chemotherapy contributes to the poor prognosis and high mortality associated with this disease.11

The new concept of cancer stem cells (CSCs) was recently put forward in an attempt to elucidate the mechanism of HCC chemoresistance, metastasis and recurrence. CSCs, which represent a small population of tumor cells, are capable of self-renewal and can proliferate and differentiate into heterogeneous lines of cancer cells.12 Hepatic CSCs were first reported by Haraguchi et al.13 CSCs appear to arise by an epigenetic mechanism,14 and in recent years, several important biomarkers of hepatic CSCs, such as CD90,15 CD133,16 epithelial cell adhesion molecule17 and CD13,18 have been identified. These markers are crucial for the identification and isolation of CSCs. Another biomarker, CD24, a heavily glycosylated mucin-like cell surface protein, is expressed in many human malignancies including lymphomas,19 small cell and non-small cell lung carcinomas,20 nasopharyngeal carcinomas,21 breast cancers,22 clear cell renal carcinomas23 and hepatocellular carcinomas.24 Recently, Irene Oi Lin Ng, of Hong Kong University, noted that CD24 is upregulated in chemoresistant and recurrent HCC patients and that it is an important biomarker for hepatic CSCs. CD24-positive HCC cells have been shown to be critical for the maintenance, self-renewal, differentiation and metastasis of this cancer.25

Listeria monocytogenes (LM) is a Gram-positive facultative intracellular parasite that can cause meningitis in immunocompromised individuals.26 The bacterium can be taken up by macrophages and other phagocytic cells, primarily in the spleen and in liver Kupffer cells. Listeriolysin O, a pore-forming cytolysin encoded by the hly gene, enables the bacterium to perforate the membranes of phagocytic cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells, after which it escapes from cytoplasmic vacuoles and enters the cytoplasm. Proteins secreted by intracellular LL are degraded by proteasomes, and their constituent peptides are presented to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules.27 The phagocytosed foreign proteins can also be presented directly to MHC class II molecules.28 Because this bacterium can induce both CD4 and CD8 antigen-specific immune response, it is a promising candidate as a cancer vaccine vector. However, because LM is a foodborne bacterium that can lead to meningitis in children and the elderly, attenuation of its virulence is needed for safety considerations. Two important genes are required for the construction of the cell wall of LM: alanine racemase (dal) and D-amino acid aminotransferase (dat). These two genes are essential for the synthesis of D-alanine, which is required for the construction of the mucopeptide component of the bacterial cell wall. In the absence of dal and dat expression, replication of LM can depend only on the availability of exogenous D-alanine.29 In this study, we used an attenuated strain of L. monocytogenes referred to as replication-deficient LMΔdalΔdat (Lmdd) strain, from which the dal and dat genes have been deleted. After introduction of the dal and dat genes from Bacillus subtilis into the Lmdd strain, the strain was able to synthesize D-alanine and to replicate to a limited extent that did not cause severe organ injuries. The newly discovered hepatic CSC biomarker CD24 was selected as an overexpressed tumor antigen to be secreted by Lmdd. In this work, we demonstrate the safety and effectiveness of this new cancer vaccine and show that it may be useful in preventing HCC chemoresistance, metastasis and recurrence.

Materials and methods

Materials

The oligonucleotides and primers used in this study were synthesized by Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). DNA sequencing was performed by Genescript Inc. (Nanjing, China). The primers to amplify the coding sequence of the human CD24 gene (accession no.: P25063) were as follows: (F): 5′-ATGGGCAGAGCAATGGTGGCC-3′ and (R): 5′-AGAGTAGAGATGCAGAG-3′.

Mice and tumor cell lines

C57BL/6 mice were bred by and purchased from the Central Animal Lab of Nanjing Medical University. The experiments were conducted when the mice were 6–8 weeks old. All experimental protocols used in this study were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Nanjing Medical University.

Hepa1–6, a hepatocellular carcinoma cell line derived from C57BL/6 mice, was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The human CD24 gene was cloned into the EcoRV and NheI sites of the pCDNA3.3 vector. The plasmid pCDNA3.3-CD24 was then electroporated into Hepa1–6 cells. Cells stably expressing CD24 protein were selected using G418 (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) at a concentration of 500 µg/ml. Western blotting was performed to detect the expression of human CD24 (Supplementary Figure 1a) and fluorescence-activated cell sorting was used to sort all G418 selected cells (Supplementary Figure 1B). The C57BL/6 derived lung cancer cell line Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC), Hepa1–6 and sorted Hepa1–6-CD24 cells were irradiated at 10 000 rads by a γ irradiator (Thermo Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Proliferation assays were performed to ensure that the irradiated cells could not multiply in vitro. These irradiated cells were used as antigens in the assays described below.

Construction of Lmdd-CD24 vaccines

The shuttle vector PKSV7 containing the dal and dat genes of Bacillus subtilis was used in vaccine construction. The human CD24 gene was amplified by polymerase chain reaction and cloned into PKSV7 at the EcoRV and NotI sites. The PKSV7-CD24 plasmid was electroporated into Lmdd at 10 kV/cm, 400 Ω and 25 µF. Positive clones were screened on and picked from brain heart infusion (BHI) agar plates (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA) supplemented with 20 µg/ml chloramphenicol and 200 µg/ml D-alanine. The PKSV7-CD24 plasmid was forced to insert into the chromosome of Lmdd at 42 °C. After five passages at 42 °C with chloramphenicol and seven passages at 30 °C without chloramphenicol in BHI culture medium, recombinant Lmdd-CD24 strains were picked from a brain heart infusion agar plate. In mice, the attenuated Lmdd-CD24 strain exhibited an LD50 of about 0.5–1.0×108 colony-forming units (CFUs), whereas the LD50 of the wild-type strain is approximately 104 CFUs.30

Extraction of proteins secreted by Lmdd-CD24 and western blot analysis

The attenuated Lmdd-CD24 strains were selected and grown overnight in BHI medium at 30 °C. After centrifugation at 4000 r.p.m. at room temperature, the culture supernatants were collected and mixed with three volumes of 10% trichloroacetic acid/acetone containing 20 mM DL-dithiothreitol. The mixture was stored overnight at −20 °C. Secreted proteins were precipitated with ice-cold acetone and resuspended in SDS–PAGE sample loading buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The blots were stained with a rabbit polyclonal human CD24 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). After incubation with horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit monoclonal antibody (Beyotime) and Pierce ECL Plus Western Blotting Substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA), bound CD24 antibodies were visualized using a CCD camera.

Apoptosis and migration assays

Human CD24 protein was overexpressed in HepG2 cells after electroporation with plasmid pCDNA3.3-CD24. G418 (Sigma) was used to select HepG2 cells that stably expressed CD24. After coculture in the presence of hydrogen peroxide for three hours, HepG2, HepG2-pCDNA3.3 and HepG2-CD24 cells were harvested and fixed in 70% ethanol overnight at −20 °C and stained with propidium iodide (PI) staining buffer (1 mg/ml RNase A, 0.1% Triton X-100 and 50 µg/ml PI in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)) to identify apoptotic populations. The cells were also stained with FITC-conjugated Annexin-V for 15 min to evaluate early apoptosis. To clarify the mechanism of the pro-apoptotic effect of CD24, we measured the levels of cleaved caspase-3 and caspase-9 in each group by western blot. A wound-healing test was conducted to compare the migration rates of HepG2, HepG2-pCDNA3.3 and HepG2-CD24 cells. When cell confluence reached 80%, a scratch wound was made by scraping the cell monolayer with a plastic tip. The migration rate of the cells was monitored for 48 hours and quantified as ‘cell migration=[(the initial distance−the later distance)/the initial distance]×100%'.

In vitro infection of Lmdd-CD24

To investigate the infectivity of the Lmdd-CD24 strain, the human HCC cell lines (7721, Huh-7, HepG2), murine HCC cell line (Hepa1–6) and murine macrophage cell line (Raw264.7) were used. Mouse peritoneal macrophages, isolated as previously described,31 were also used. All of the above-mentioned cells were cultured at 1.0×106 cells/well in six-well plates and infected by Lmdd-CD24 strains at multiplicity of infection (MOI)=1∶1. One hour later, uninfected cells were washed away. The infected cells were then lysed in double-distilled water for three hours and diluted 1∶1000. The diluted cell suspensions were plated and cultured in BHI plates. CFUs were counted 2–3 days later.

In vivo infection and distribution of Lmdd-CD24

A dose of 5.0×107 CFUs of Lmdd-CD24 strains was intravenously injected into 6- to 8-week-old mice (n=3). On the first and third days after the first immunization, single-cell suspensions were harvested from spleen, liver, kidneys, lungs and brain and cultured on BHI agar plates without chloramphenicol and D-alanine. The CFUs/g for each organ was calculated to determine the differences in organ distribution of the injected Lmdd-CD24. Three days after intravenous injection, the major organs were collected and fixed in formalin for hematoxylin and eosin staining and electron microscopy.

Mouse immunization and tumor challenge

C57BL/6 mice were inoculated subcutaneously in the left inguinal region with 5×106 sorted Hepa1–6-CD24 cells 3 days after or before their first immunization. The mice (n=5) then were intravenously injected with 5.0×107 CFUs of the Lmdd-CD24 or Lmdd strain. As a control, 0.1 ml of PBS was also intravenously injected. In the prophylactic group, mice were immunized 3 days before inoculation with Hepa1–6-CD24 tumor cells, whereas in the therapeutic group, mice were immunized 3 days after tumor challenge. The immunizations were repeated two additional times at 1-week intervals (Supplementary Figure 2). Four weeks later, mouse splenocytes were isolated from the immunized mice for in vitro assays. Tumor diameter was measured by a caliper every 3 days and recorded as the mean of the longest and narrowest surface lengths. The mice were sacrificed when the average tumor diameter reached 20 mm.

Isolation of splenocytes and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

At various time points following immunization, mice were killed and their splenocytes were aseptically isolated. Splenocytes were filtered through cell strainers (BD Falcon, San Jose, CA, USA) and digested with red blood cell lysis buffer (Sigma) to obtain a single-cell suspension. The cells were then centrifuged with Ficoll-Paque Plus (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh PA, USA) at 2000 r.p.m. for 20 min at room temperature. When centrifugation was complete, four different layers could be observed; the third layer was occupied by lymphocytes. Tumors from mice inoculated with Hepa1–6-CD24 cells were excised and digested with collagenase A and type V hyaluronidase (Sigma) for 45 min at 37 °C. The digested tumor cells were filtered through and centrifuged with Ficoll-Paque Plus as described above to isolate tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.

ELISPOT assays

Splenocytes were harvested from mice (n=3) of the PBS, Lmdd and Lmdd-CD24 groups 1 week after the final immunization and a MACS kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA) was applied to isolate CD8+ T lymphocytes. CD8+ T lymphocytes were cultured overnight in 24-well plates at 1.0×106 cells/well with 20 U/ml recombinant mouse IL-2 and irradiated Hepa1–6-CD24 cells (5×104 cells/well). Irradiated LLC and Hepa1–6 cells (5×104 cells/well) were used as controls. The number of splenic interferon (IFN)-γ-producing CD8+ T cells was investigated using a mouse IFN-γ ELISPOT kit (R&D, Minneapolis, MN, USA). To count the number of IL-4 and IL-10 secreting cells, splenocytes from the various experimental groups (n=10) were also cocultured overnight with 1 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate. and 0.5 ng/ml ionomycin (Sigma). ELISPOT kits for IL-4 and IL-10 were purchased from R&D (Minneapolis). Assays were conducted according to the manufacturer's directions. Six days after the final vaccination, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were isolated as previously described and cocultured in 96-well plates (107 cells/well) overnight with irradiated Hepa1–6-CD24 cells in the presence of 5 U/ml rmIL-2. The number of CD8+ T cells isolated from TILs was measured using a CD8 ELISPOT kit (R&D). The plates were counted using an ELISPOT reader, and the results are expressed as spot-forming units per 106 cells after subtraction of background spots.

ELISA assay

One week after the final immunization, splenocytes were isolated from mice in the PBS, Lmdd and Lmdd-CD24 groups. The isolated splenocytes were co-cultured with 20 U/ml rmIL-2 in a six-well plate and stimulated by irradiated Hepa1–6-CD24 cells (5×104 cells/well) for 3 days. Supernatants were collected from each well, and the concentration of IFN-γ in the supernatants was measured using an IFN-γ ELISA kit (R&D) according to the manufacturer's manual.

Cell staining and flow cytometry

TILs were isolated from mice in the control, prophylactic and therapeutic groups. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) of TILs were identified by flow cytometry after being stained with PE-Cy5.5-conjugated CD4, APC-conjugated CD25 and PE-conjugated Foxp3 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA).

Immunohistochemistry of Tregs

Tumor bearing mice were sacrificed when the even diameter of the tumor reached 20 mm and paraffin-embedded sections of the tumors from the control, prophylactic and therapeutic groups were prepared. Sections were deparaffinized and subjected to heat-induced antigen retrieval using DAKO's target retrieval solution for 25 min. After endogenous peroxidase removal using 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 10 min, samples were incubated twice: first for 15 min with avidin-biotin blocking reagent (Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA) and then for 15 min with protein-blocking reagent (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA, USA). Slides were stained with CD4 (Abcam, San Francisco, CA, USA) and Foxp3 (Abcam) primary antibodies at a dilution of 1∶100, and immunodetection was performed using a secondary biotinylated polyclonal goat anti-mouse/rat IgG (Sigma). Diaminobenzidine/hydrogen peroxidase was used as the chromogen reagent.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) releasing assay to detect cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells from TILs

TILs were isolated from tumor bearing mice. CD8+ T cells from TILs were isolated using a MACS kit (Miltenyi Biotec) and restimulated by irradiated Hepa1–6 or Hepa1–6-CD24 cells overnight to serve as effector cells. Hepa1–6-CD24 cells served as target cells. Effector cells and targeted cells were incubated at various E/T ratios (50∶1, 25∶1 and 5∶1) for 18 h. The LDH level in the supernatants was measured following directions in the manual provided with the LDH kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Spontaneous LDH release from target or effector cells was subtracted from the measured values, and the final results were expressed as the percentage of specific lysis, calculated as (experimental release−target spontaneous release−effector spontaneous release)/(target maximum release−target spontaneous release).

Statistical analysis

Results of each experiment are expressed as the mean±s.d. GraphPad Prism 4.0 software (2005) (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used to compare the differences between groups by one-way analysis of variance followed by an unpaired t-test. Values of P<0.05 were considered significant. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and significance was evaluated using the log-rank or the χ2 test.

Results

CD24 reduces apoptosis and enhances migration of human HCC cells

CD24 has the capacity to affect the apoptosis and migration of tumor cells. To investigate the role of CD24 in HCC cells, we measured cell apoptosis rates by flow cytometry and conducted wound-healing tests to assess cell migration. After electroporation of human HCC cell line HepG2 cells in the presence of pCNDA3.3-CD24 plasmid, CD24 was overexpressed in those cells. Based on the results obtained from flow cytometry, HepG2-CD24 cells (Figure 1 a) had a lower apoptosis rate than HepG2 and HepG2-pCDNA3.3 cells (41.80±2.038 HepG2, 40.20±1.772 HepG2-pCDNA3.3, 17.00±2.098 HepG2-CD24) (Figure 1b). Cleaved caspase-9 could process other members of the caspase family, including caspase-3 and caspase-7, to initiate a caspase cascade, which led to apoptosis. Increased levels of cleaved caspase-3 and caspase-9 proteins were observed by western blot in HepG2 and HepG2-pCDNA3.3 cells (Figure 1c). In the wound-healing test, HepG2-CD24 cells displayed a higher migration rate than cells in the other two groups (Figure 1d). These results suggest that CD24 can reduce apoptosis and promote migration of tumor cells.

Figure 1.

The role of CD24 in tumor cell apoptosis and metastasis. (a) Western blot analysis of the expression of CD24 in HepG2 cells. CD24 was overexpressed after electroporation of pCDNA3.3-CD24 into the human HCC cell line HepG2. HepG2 and HepG2-CD24 cells were harvested and proteins were extracted. CD24 primary antibody was used to bind the protein and bound antibodies were visualized using a CCD camera. HepG2 and HepG2-pCDNA3.3 cells were used as a control. (b) Impact of CD24 on apoptosis of HepG2 cells assessed by flow cytometry. The rates of apoptosis of HCC cell lines HepG2, HepG2-pCDNA3.3 and HepG2-CD24 were compared. The cells were fixed in 70% ethanol and stained with PI overnight and with FITC-conjugated annexin-V for 15 min. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that HepG2-CD24 cells had a lower rate of apoptosis than HepG2 and HepG2-pCDNA3.3 cells. (c) Levels of cleaved caspase-3 and caspase-9 in each experimental group. Proteins were extracted and cleaved caspase-3 and caspase-9 were detected by western blot analysis. Significantly increased levels of caspase-3 and caspase-9 protein were observed in HepG2 and HepG2-pCDNA3.3 cells. (d) Wound-healing tests comparing the migration of HepG2, HepG2-pCDNA3.3 and HepG2-CD24 cells. Scratch wounds were created on the cell monolayers. The migration of HepG2, HepG2-pCDNA3.3 and HepG2-CD24 cells was observed 48 h later, and the cultures were photographed under a microscope (×100 magnification). HepG2-CD24 cells proved to be more capable of migration than the other cells. Each experiment was repeated at least three times. Data are expressed as the mean±s.d. *P<0.05. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; PI, propidium iodide.

Construction of attenuated Lmdd strains secreting CD24 proteins

The attenuated Lmdd strain was designed to secrete CD24, a surface biomarker of hepatic cancer stem cells. The full coding sequence of CD24 was cloned into the special shuttle vector PKSV7 at the restriction sites of EcoRV and NotI. Hly, a signal-promoter gene, is upstream of the EcoRV enzyme digestion site and can drive the expression of listeriolysin O and of the cloned CD24 gene (Figure 2a). When the intact plasmid PKSV7-CD24 was electroporated into the cells, the CD24 gene was integrated into the Lmdd chromosome with the help of the sepA gene. Because the vector plasmid PKSV7 contains the dal and dat genes of B. subtilis, successful recombination allowed the Lmdd strains to replicate to a limited extent without a need for exogenous D-alanine. Continuous passage in antibiotic-free medium led the Lmdd-CD24 strains to lose the antibiotic resistance of the shuttle vector plasmid PKSV7. After allelic recombination, secreted proteins were extracted from the culture supernatants and analyzed by western blotting (Figure 2b). Stable and durable secretion of CD24 protein is essential for an effective Lmdd-CD24 vaccine. Proteins from the tenth, twentieth, thirtieth and fortieth passages were extracted from the strains and western blot assays showed that Lmdd-CD24 strains stably and reliably secreted CD24 (Figure 2c). We also compared the colony-forming abilities of the tenth, twentieth, thirtieth and fortieth generations of Lmdd-CD24 to that of Lmdd by counting colonies on BHI plates. There were no significant differences in the counts obtained from the genetically modified Lmdd-CD24 vaccine and Lmdd (P>0.05). This result shows that our genetic modification of Lmdd did not alter the stability of the bacteria on passaging (Figure 2d). Comparison of the CFUs obtained from Lmdd-CD24-infected cell lines in BHI plates suggested that there were also no significant differences between HepG2, SMMC-7721, Huh-7, Hepa1–6, Raw264.7 and freshly isolated mouse peritoneal macrophages (P>0.05). The highly invasive HCC cell lines HepG2 and SMMC-7721 were most vulnerable to the Lmdd-CD24 vaccines. HepG2 and SMMC-7721, respectively, took up (2.425±0.222)×104 and (2.0±0.445)×104 CFUs. However, isolated peritoneal macrophages (MΦ) and the murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 phagocytosed (1.275±0.171)×107 and (2.375±0.263)×107 CFUs, respectively (Figure 2e).

Figure 2.

Construction and characterization of the Lmdd-CD24 vaccine. (a) Schematic map of the PKSV7-CD24 plasmid. The coding sequence of CD24 was cloned into the EcoRV and NotI restriction sites. CD24 expression was under the control of the hly promoter. (b) The expression and secretion of CD24 protein were identified by western blotting. CD24 protein was collected from the supernatant and detected by an anti-CD24 rabbit-derived polyclonal antibody. Blots were illuminated and visualized using a CCD camera. Lmdd was used as a control. (c) Western blot to verify the stable secretion of CD24 by Lmdd-CD24. Supernatants from the tenth, twentieth, thirtieth and fortieth passages of Lmdd-CD24 were collected. The blots shown represent the expression of CD24 secreted by Lmdd-CD24 strains of different passages. (d) In vitro passages of Lmdd and Lmdd-CD24. Comparison of the CFUs on BHI plates showed that after increasing numbers of passages (10, 20, 30 and 40 passages), CFUs of Lmdd and Lmdd-CD24 strains did not differ significantly. In other words, genetic modification of Lmdd did not alter its stable passaging property. *P>0.05. (e) In vitro infectivity of Lmdd and Lmdd-CD24. Lmdd and Lmdd-CD24 were used to infect the human tumor cell lines (HepG2, SMMC-7721, Huh-7) and the murine derived hepatocellular carcinoma cell line Hepa1–6, respectively. The murine derived macrophage cell line Raw264.7 and freshly isolated mouse macrophages (MΦ) were also used. The cells were cultured in six-well plates at 1.0×106 cells/well and infected with Lmdd and Lmdd-CD24 at MOI=1∶1. The infected cells were lysed in double-distilled water and diluted 1∶1000. The dilutions were plated in BHI plates and CFUs were counted. The experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated three times. The data are expressed as the mean±s.d of the CFUs. BHI, brain heart infusion; CFU, colony-forming unit; Lmdd, Listeria monocytogenes strain ΔdalΔdat; MOI, multiplicity of infection.

In vivo organ distribution and safety of Lmdd-CD24 vaccine after intravenous injection

LM is responsible for several foodborne diseases and can even cause severe symptoms such as those associated with listeriolysis. Therefore, it is essential to ensure the safety of the Lmdd-CD24 vaccine. After intravenous injection of 5.0×107 CFUs of Lmdd-CD24, most bacteria were distributed to distant organs, primarily translocated into the spleen and liver and replicated in macrophages and hepatocytes, where they can remain for about 3 days. In this assay, some major organs of the infected mice, including spleen, liver, lung and brain, were collected. CFUs/g on the first and third days after intravenous injection was calculated for these organs. The results showed that the infected Lmdd-CD24 mainly resided in the spleen and liver, whereas only a small amount of bacteria was found in the kidneys and lungs and none was found in the brain. Using electron microscopy, numerous Lmdd-CD24 strains were observed in the spleen (Figure 3a). Although Lmdd-CD24 is attenuated by several genetic modifications, it is not clear whether it can cause serious organ injuries and untoward effects such as listeriolysis, meningitis and even death after intravenous injection. To investigate the safety of this vaccine, 5.0×107 CFUs of Lmdd-CD24 vaccine was intravenously administered. Three days later, the major organs (liver, spleen and kidney) of the immunized mice were collected and fixed in formaldehyde. Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed that there was only a weak inflammatory response and no structural damage or necrosis in the liver. The spleen exhibited only infiltration of lymphocytes, whereas in the kidneys, mild injuries were evident compared with the normal control (Figure 3b). No deaths of mice were observed after intravenous injection. These results confirm that the Lmdd-CD24 vaccine is safe and reliable and that it has potential for clinical application.

Figure 3.

Organ distribution of Lmdd-CD24 strains after intravenous injection. (a) Lmdd-CD24 strains (5×107 CFUs) were intravenously administered to mice, and CFUs/g of Lmdd-CD24 in various organs were counted on the first and third days after injection. Homogenized tissues from different mouse organs (spleen, liver, kidneys, lungs and brain) were placed on BHI plates and incubated at 37 °C overnight. Using electron microscopy, large numbers of Lmdd-CD24 strains were observed in spleen tissue. Experiments were repeated three times. The data are expressed as the mean±s.d of the CFUs. (b) The safety of attenuated Lmdd-CD24 bacteria in mice assessed by hematoxylin and eosin staining. Immunized mice were sacrificed 3 days after intravenous administration of 5.0×107 CFUs of Lmdd-CD24. To investigate possible injuries, vital organs (liver, spleen and kidney) were collected for hematoxylin and eosin staining. Slight inflammatory responses were observed in some hepatocytes. The hepatic central venous system was intact and no tissue necrosis or structural damage was seen. In the spleen, only infiltration of lymphocytes occurred. Compared to the normal control, mild injuries were observed in the kidney. These pictures show representative tissue samples from three mice in the vaccinated and normal groups. Black arrows indicate sites of inflammation or lymphocyte infiltration. BHI, brain heart infusion; CFU, colony-forming unit; Lmdd, Listeria monocytogenes strain ΔdalΔdat.

Lmdd-CD24 can induce Th1 and Th2 cell-mediated immune responses

The immunotherapeutic efficacy of cancer vaccines depends largely on the promotion of antigen-specific immune responses. Due to its unique characteristic of spreading from cell to cell without entering the outside environment and its ability to present antigens through the MHC class I pathway,32 the Lmdd-CD24 vaccine induces an immune response characterized by Th1- and Th2-type cell activation.33 To objectively assess the immunological role of Lmdd-CD24, we measured the number of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells, the IFN-γ level in culture supernatants and the levels of IL-4 and IL-10 cytokines secreted by Th2 cells. IFN-γ is critical for innate and adaptive immune responses to intracellular bacterial infections and tumor control. After coculture of splenic CD8+ T lymphocytes isolated by a MACS kit with irradiated LLC, Hepa1–6 and Hepa1–6-CD24 cells, the Lmdd-CD24 immunized group stimulated with irradiated Hepa1–6-CD24 cells displayed the most IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells (453±55 SFC/106 cells) and the highest level of IFN-γ (1334±152 pg/ml) in the cell supernatants. Splenocytes from mice in the PBS or Lmdd immunized groups produced little IFN-γ even after stimulation by irradiated Hepa1–6-CD24 cells (Figure 4a and b). Th1 cells can produce IFN-γ, whereas Th2 cells mainly secret cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-6 and IL-10. One week after the final immunization, we isolated splenocytes from each group and measured the number of cells secreting IL-4 and IL-10 cytokines by ELISPOT. Mice in the Lmdd-CD24 vaccinated group displayed more IL-4- and IL-10-secreting Th2 cells than the mice in the other two groups (P<0.01) (Figure 4c). These results suggest that our recombinant and attenuated Lmdd-CD24 vaccine may elicit both Th1 and, to some extent, Th2 cell responses.

Figure 4.

Th1- and Th2 cell-mediated immune responses to the Lmdd-CD24 vaccine. (a) ELISPOT assay for quantitation of IFN-γ producing CD8+ splenic T lymphocytes in different groups. Splenocytes harvested from mice in the PBS, Lmdd and Lmdd-CD24 groups (n=3) were sorted by a CD8 MACS kit, cultured overnight in 24-well plates at 5×106 cells/well with 20 U/ml rmIL-2 and stimulated by irradiated Hepa1–6-CD24 cells. Splenocytes were also co-cultured with irradiated LLC and Hepa1–6 cells as a control. Using the IFN-γ ELISPOT kit, the Lmdd-CD24 vaccinated group displayed more IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells than other groups after stimulation by irradiated Hepa1–6-CD24 cells. When stimulated by irradiated LLC or Hepa1–6 cells, no obvious spot-forming units were observed in the PBS, Lmdd and Lmdd-CD24 groups. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (b) ELISA assay to detect IFN-γ levels in supernatants of stimulated splenocytes from various immunized groups. Splenocytes (n=3) were cocultured with irradiated Hepa1–6-CD24 cells for 3 days and the culture supernatants were harvested for ELISA assay. Irradiated LLC and Hepa1–6 cells were used as controls. After stimulation by irradiated Hepa1–6-CD24 cells, splenocytes from the Lmdd-CD24 vaccinated group produced the highest levels of IFN-γ. When stimulated by irradiated control cells (LLC and Hepa1–6), no increased levels of IFN-γ were detected in any group. The assays were repeated at least three times in triplicate. The data are expressed as the mean±s.d. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (c) ELISPOT assay to measure the number of IL-4- and IL-10-secreting Th2 cells. Splenocytes were harvested from control or immunized groups (n=10) 1 week after immunization and cocultured in the presence of 1 ng/ml PMA and 0.5 ng/ml ionomycin overnight. The levels of cytokines (IL-4 and IL-10) secreted by the Th2 cells of each group were measured by ELISPOT assays. Individual and mean values are shown. IFN, interferon; LLC, Lewis lung carcinoma; Lmdd, Listeria monocytogenes strain ΔdalΔdat; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PMA, phorbol myristate acetate.

Lmdd-CD24 causes regression of inoculated Hepa1–6-CD24 tumors in mice

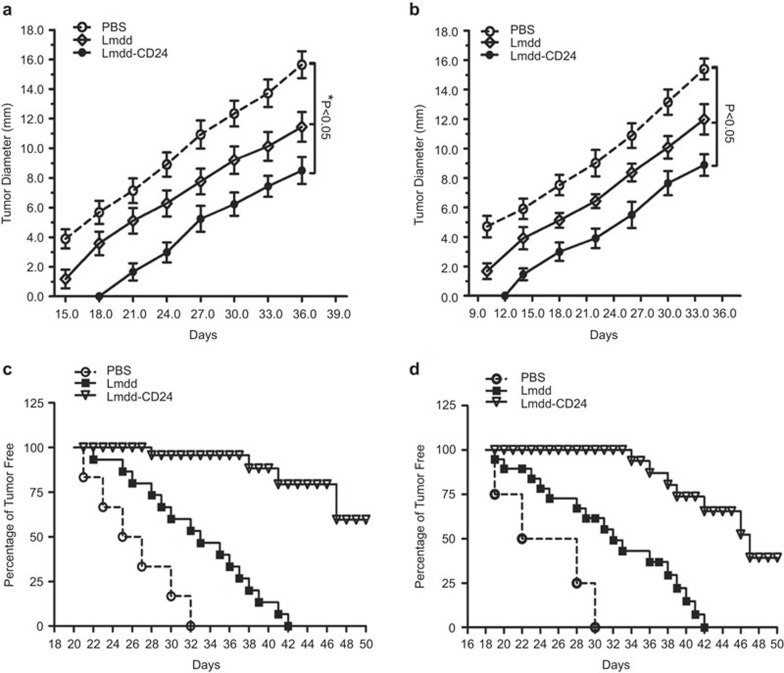

To study the prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy of the Lmdd-CD24 vaccine, we subcutaneously inoculated 5×106 Hepa1–6-CD24 tumor cells into the left inguinal regions of mice 3 days before or after vaccination to establish a tumor-bearing model. All mice were vaccinated intravenously with 5.0×107 CFUs of Lmdd-CD24 or control vaccine and the immunizations were repeated twice at 1-week intervals. In the prophylactic and therapeutic groups, Lmdd-CD24 significantly reduced the size and slowed the growth of the tumors compared to PBS or Lmdd (Figure 5a and b) (P<0.05). Evaluation of the tumor-free survival of mice showed that the Lmdd-CD24 vaccinated mice in both the prophylactic and the therapeutic groups achieved longer survival than the mice in the control group (Figure 5c and d).

Figure 5.

Lmdd-CD24 results in regression of subcutaneously inoculated Hepa1–6-CD24 tumors and increased tumor-free survival. Mice (n=5) were vaccinated with PBS, Lmdd control or Lmdd-CD24 vaccines and grouped into prophylactic and therapeutic groups. Hepa1–6-CD24 cells (5×106) were inoculated subcutaneously 3 days before or after the first vaccination to establish a prophylactic or therapeutic model. The longest and narrowest surface lengths of the tumors were measured in triplicate every 3 days. The data were expressed as the mean of the longest and narrowest tumor surface length. (a) Tumor growth of mice in the prophylactic group. (b) Tumor growth of mice in the therapeutic group. (c) Long-term tumor-free survival of mice in the prophylactic group. (d) Long-term tumor-free survival of mice in the therapeutic group. The error bars indicate s.d. Long-term tumor-free survival was monitored until day 50. Lmdd, Listeria monocytogenes strain ΔdalΔdat; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Immunological roles of Tregs and CD8+ T cells isolated from TILs in preventing tumor regression caused by the Lmdd-CD24 vaccine

A variety of mechanisms affect cancer progression and regression. Recent discoveries have shed some light on a population of cells called Tregs, which are characterized by co-expression of CD4 and the IL-2 receptor α-chain (CD25). We initially isolated TILs from tumors stained with CD4, CD25 and forkhead box (Fox)p3 antibodies and analyzed these cells by flow cytometry. By comparing the percentages of Tregs isolated from mice in the different experimental groups, we found that mice in the control group had more Tregs than those in the prophylactic and therapeutic groups (8.414%±0.268% in the control group, 3.612%±0.280% in the prophylactic group, 3.392%±0.288% in the therapeutic group) (Figure 6a). A similar result was obtained in the immunohistochemistry assay. Lower positive staining levels of CD4− and Foxp3− double positive cells were observed in the prophylactic and therapeutic groups (Figure 6b). These results suggest that the Lmdd-CD24 vaccine significantly reduces the level of Treg cells, which are negative regulators in anti-tumor immunity. TILs from the prophylactic and therapeutic groups were cocultured with irradiated Hepa1–6-CD24 cells and the number of CD8+ T cells from TILs was measured by ELISPOT assay. Lmdd-CD24-vaccinated mice had more CD8+ T cells isolated from TILs in their tumor areas than did the other two groups of mice (P<0.05) (Figure 6c). This finding suggests that the Lmdd-CD24 vaccine can induce antigen-specific CD8+ T cells from TILs to participate in anti-tumor immunity at local tumor sites. In addition, the LDH-releasing assay demonstrated that restimulated CD8+ T cells from TILs in tumor areas could effectively eliminate CD24-expressing target cells (Figure 6d). Thus, the Lmdd-CD24 vaccine reduces the recruitment of Tregs and induces the presence of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells among the TILs isolated from tumor areas.

Figure 6.

Regulatory and CD8+ T cells in TILs. TILs were isolated from tumors of mice in the control, prophylactic and therapeutic groups by gradient density centrifugation. (a) Flow cytometry analysis of the frequency of CD4+ Foxp3+ Tregs in tumors from mice (n=5) of each group. Flow cytometry was performed after staining of CD4 by a cell surface antibody and of Foxp3 by an intracellular antibody. The numbers of Foxp3+/CD4+ double-positive cells were calculated as a percentage and TILs were counted as a basis for the percentage. (b) Immunostaining of CD4+ and Foxp3+ Tregs. Tumor tissues were fixed in formalin and paraffin-embedded sections were prepared and stained with CD4 or Foxp3 antibodies. The IOD of each section was calculated with the aid of computer software for five fields (×100). Comparison of the control, prophylactic and therapeutic groups was performed using Image-Pro Plus software (version 6.0). Data were expressed as the mean±s.d. (c) ELISPOT assay measuring the number of CD8+ T cells isolated from TILs. When the mice from each group were sacrificed, TILs were isolated. CD8 ELISPOT assay demonstrated that the Lmdd-CD24 vaccinated mice in the prophylactic and therapeutic groups recruited more CD8+ T cells from TILs in the tumor area than did the mice in the other two groups. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (d) LDH-releasing assay measuring the cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells isolated from TILs against target cells. CD8+ T cells from TILs were isolated by MACS after the mice were killed and restimulated by irradiated Hepa1–6 or Hepa1–6-CD24 cells to serve as effector cells. The effector cells and target cells (Hepa1–6-CD24) were incubated for 18 h at ratios of 50∶1, 25∶1 and 5∶1. The LDH levels in the cell culture supernatants were measured using an LDH detection kit as directed by the manufacturer. The data are presented as the mean±s.d. Student's t-test and Image-Pro Plus software (version 6.0) were used to analyze the data. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. IOD, intensity of the optical density; LDH, Lactate dehydrogenase; Lmdd, Listeria monocytogenes strain ΔdalΔdat; TIL, tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte; Treg, regulatory T cell.

Discussion

Hepatocellular carcinoma, the fifth most common cancer worldwide, represents a serious threat to public health. The use of specific treatments for HCC, such as resection, liver transplantation and percutaneous ablation, varies geographically.34 Despite the availability of these treatment methods, chemoresistance, metastasis and recurrence result in poor prognosis in many HCC patients. The cancer stem cell hypothesis posits that cancers are maintained in a hierarchical organization of ‘cancer stem cells' that can rapidly differentiate into amplifying cells and differentiated tumor cells.35 CSCs can initiate and sustain tumor growth and are responsible for the prognosis of cancers.36 CD24 is a newly discovered biomarker that is overexpressed in hepatic CSCs and is closely related to HCC chemoresistance, metastasis and recurrence. CD24-positive HCC cells are critical for the maintenance, self-renewal and differentiation of tumors and may significantly impact the clinical outcome of HCC patients. Hence, if CD24-positive cells could be specifically and effectively targeted, chemoresistance, metastasis and recurrence of HCC might be prevented. By incorporation into a suitable vector, the CD24 protein could be effectively delivered and used to elicit a strong innate and adaptive immune response. With the development of microbiology and immunology, pathogens could be inactivated and attenuated for vaccines. LM, an intracellular parasite, is an eligible candidate for such a vaccine vector. For clinically used vaccines, safety is an essential priority that must be seriously considered. In this study, attenuated LM, which is herein referred to as Lmdd, was applied as a vaccine vector to secrete tumor-associated antigen. It was attenuated by deletion of the dal and dat genes, which are essential for the synthesis of D-alanine. Upon introduction of the shuttle vector PKSV7, which contains the B. subtilis dal and dat genes, Lmdd replicated only to a limited extent and did not cause serious injury. LM could also be attenuated by deletion of the actA/plcB genes and retained its immunogenicity. The actA gene is responsible for actin polymerization, organelle movement within eukaryotic cells and intercellular spread.37 The plcB gene encodes a phospholipase or lecithinase38 and has been shown to be very important for secondary vacuolar escape.39 LMΔactA/plcB was less attenuated than Lmdd, as shown by the fact that its LD50 was around 1.47×104 CFUs. The virulence of LM was reduced by deletion of either the dal/dat or the actA/plcB genes. These features may be clinically applied in the future. After intravenous injection, Lmdd-CD24 was rapidly phagocytosed by immune cells, such as dendritic cells and macrophages, and could elicit both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses without obvious toxicity. Proteins secreted by Lmdd could be presented through the MHC-I molecular pathway in its intracellular phase, as well as directly through the MHC-II molecular pathway. For these reasons, Lmdd was chosen for delivery of the hepatic CSC biomarker CD24. The Lmdd-CD24 cancer vaccine represents a novel immunotherapeutic agent for the prevention and treatment of HCC chemoresistance, metastasis and recurrence.

When Lmdd-CD24 strains were intravenously administered into mice, the injected bacteria replicated and accumulated in peripheral lymphocytes. The injected Lmdd-CD24 strains were mainly distributed to the spleen, liver and lung and did not cause serious organ injuries. By presenting the CD24 protein, Lmdd-CD24 induced a specific T cell-mediated immune response. IFN-γ is a crucial cytokine in Th1 cell-mediated immunity against tumor cell proliferation. After intravenous administration of Lmdd-CD24, the number of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T lymphocytes and the level of IFN-γ were significantly increased. Using splenocyte ELISPOT assays, we found that Lmdd-CD24 strains stimulated the host to produce low levels of Th2 cell-secreted cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10. However, this weak Th2-cell-mediated immune response may be essential and may play an auxiliary role in anti-tumor immunity.

Recombinant LM has been shown to have an exceptional capacity to induce anti-tumor immunity to tumor-associated antigens such as HPV16 E7,40 influenza virus NP341 and HIV-1 gag.42 Kim et al. found that LM based vaccines could not only remove primary tumors, but also eliminate metastases and residual tumor cells.43 In this research, Lmdd-CD24 vaccine caused the regression of inoculated Hepa1–6-CD24 tumors, prevented tumor occurrence and growth in the prophylactic and therapeutic groups and increased tumor-free survival of the mice. This might be explained by the suppressed recruitment of Tregs in the immunized mice and the stimulation of CD8+ T cells isolated from TILs in local tumor areas. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs had an adverse effect on the prognosis of many tumors,44 including HCC.45 In the current study, we found a decrease of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs in tumors of mice that were vaccinated with Lmdd-CD24. In ELISPOT and LDH-release assays, Lmdd-CD24 vaccine increased the number of CD8+ T cells isolated from TILs. These results indicate that the Lmdd-CD24 vaccine can suppress the recruitment and differentiation of Tregs in tumors and stimulate CD8+ T cells from TILs, thus reducing tumor size and extending host survival. The animal model described above differs greatly from hepatocellular carcinoma in humans. However, our goal in establishing a tumor bearing animal model by inoculating Hepa1–6-CD24 cells, which overexpress CD24 protein, is to show that Lmdd-CD24 strains could effectively induce the regression of inoculated tumors and elicit anti-tumor immunity. The results demonstrate that Lmdd-CD24 strains can specifically target tumor cells that express CD24 antigen. Vaccine adjuvants, such as cyclophosphamide and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor, can enhance the anti-tumor effects of the vaccines, and recently curcumin was demonstrated to improve the therapeutic efficacy of LM.46 Based on these findings, we hypothesize that the prophylactic and therapeutic effects of Lmdd-CD24 vaccine might also be enhanced by some adjuvants.

In conclusion, Lmdd-CD24 can stably secrete the CD24 protein, a hepatic CSC marker, as a tumor-associated antigen to elicit a specific immune response. Lmdd-CD24 is a safe and effective vaccine that reduces tumor size and extends tumor-free survival in mice. The Lmdd-CD24 strain has the potential to prevent HCC chemoresistance, metastasis and recurrence and merits further investigation as a cancer vaccine vector for future clinical application.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation (81072029 to BS, 30901750 and 81272322 to YC and 81201528 to RJ), the National Basic Research Program of China (2012CB910800 to BS), the Major Research Plan of the National Natural Science Foundation (91029721 to BS), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK2010532 to YC), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation-funded Project (20090461133 to YC), the Jiangsu Planned Projects for Postdoctoral Research Funds (1001028B to YC) and the Jiangsu Province Laboratory of Pathogen Biology (11BYKF02 to QS).

All authors have contributed substantially to this work and declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Cellular & Molecular Immunology's website.

Supplementary Information

References

- El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2557–2576. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal AJ, Yoon SK, Lencioni R. The etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma and consequences for treatment. Oncologist. 2010;15 Suppl 4:14–22. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-S4-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Yang D, Li S, Gao Y, Jiang R, Deng L, et al. Development of a Listeria monocytogenes-based vaccine against hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2012;31:2140–2152. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llovet JM, Fuster J, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepato-gastroenterology. 2002;49:7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebinuma H, Saito H. Prevention for the development of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma by anti-viral treatment. Nihon Rinsho. 2011;69 Suppl 4:540–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgard P, Muller S, Hamami M, Sauerwein WS, Haberkorn U, Gerken G, et al. Selective internal radiotherapy (radioembolization) and radiation therapy for HCC—current status and perspectives. Z Gastroenterol. 2009;47:37–54. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1028002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche A. Therapy of HCC–TACE for liver tumor. Hepato-gastroenterology. 2001;48:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer HU, Seiler C, Buchler MW. Modern liver surgery for HCC. Swiss Surg. 1999;5:91. doi: 10.1024/1023-9332.5.3.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang P, Hu JH, Cheng ZG, Liu ZF, Wang JL, Jiao SC. Efficacy and safety of bevacizumab for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of phase II trials. PloS ONE. 2012;7:e49717. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li QG, Yang GS, Yang Q, Wei LX, Yang N, Zhou XP, et al. Disseminated tumor cells homing into rats' liver: a new possible mechanism of HCC recurrence. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:903–905. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i6.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Lee TK, Zheng BJ, Chan KW, Guan XY. CD133+ HCC cancer stem cells confer chemoresistance by preferential expression of the Akt/PKB survival pathway. Oncogene. 2008;27:1749–1758. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon SK. The biology of cancer stem cells and its clinical implication in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut Liver. 2012;6:29–40. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2012.6.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraguchi N, Utsunomiya T, Inoue H, Tanaka F, Mimori K, Barnard GF, et al. Characterization of a side population of cancer cells from human gastrointestinal system. Stem Cells. 2006;24:506–513. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crea F, Danesi R, Farrar WL. Cancer stem cell epigenetics and chemoresistance. Epigenomics. 2009;1:63–79. doi: 10.2217/epi.09.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang ZF, Ho DW, Ng MN, Lau CK, Yu WC, Ngai P, et al. Significance of CD90+ cancer stem cells in human liver cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Chan KW, Hu L, Lee TK, Wo JY, Ng IO, et al. Identification and characterization of tumorigenic liver cancer stem/progenitor cells. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2542–2556. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita T, Ji J, Budhu A, Forgues M, Yang W, Wang HY, et al. EpCAM-positive hepatocellular carcinoma cells are tumor-initiating cells with stem/progenitor cell features. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1012–1024. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraguchi N, Ishii H, Mimori K, Tanaka F, Ohkuma M, Kim HM, et al. CD13 is a therapeutic target in human liver cancer stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3326–3339. doi: 10.1172/JCI42550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Went P, Dellas T, Bourgau C, Maurer R, Augustin F, Tzankov A, et al. Expression profile and prognostic significance of CD24, p53 and p21 in lymphomas. A tissue microarray study of over 600 non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2004;129:2094–2099. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-831850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D, Waibel R, Weber E, Bell J, Stahel RA. CD24, a signal-transducing molecule expressed on human B cells, is a major surface antigen on small cell lung carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1992;52:5264–5270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karran L, Jones M, Morley G, van Noorden S, Smith P, Lampert I, et al. Expression of a B-cell marker, CD24, on nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer. 1995;60:562–566. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaipparettu BA, Malik S, Konduri SD, Liu W, Rokavec M, van der Kuip H, et al. Estrogen-mediated downregulation of CD24 in breast cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:66–72. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Kim DI, Kwak C, Ku JH, Moon KC. Expression of CD24 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma and its prognostic significance. Urology. 2008;72:603–607. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XR, Xu Y, Yu B, Zhou J, Li JC, Qiu SJ, et al. CD24 is a novel predictor for poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma after surgery. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5518–5527. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TK, Castilho A, Cheung VC, Tang KH, Ma S, Ng IO. CD24+ liver tumor-initiating cells drive self-renewal and tumor initiation through STAT3-mediated NANOG regulation. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:50–63. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahan CG, Hill C. The use of listeriolysin to identify in vivo induced genes in the Gram-positive intracellular pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:498–507. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamer EG, Sijts AJ, Villanueva MS, Busch DH, Vijh S. MHC class I antigen processing of Listeria monocytogenes proteins: implications for dominant and subdominant CTL responses. Immunol Rev. 1997;158:129–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts C. The exogenous pathway for antigen presentation on major histocompatibility complex class II and CD1 molecules. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:685–692. doi: 10.1038/ni1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RJ, Bouwer HG, Portnoy DA, Frankel FR. Pathogenicity and immunogenicity of a Listeria monocytogenes strain that requires D-alanine for growth. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3552–3561. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3552-3561.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Zhang M, Zhou C, Zhao X, Iijima N, Frankel FR. Novel vaccination protocol with two live mucosal vectors elicits strong cell-mediated immunity in the vagina and protects against vaginal virus challenge. J Immunol. 2008;180:2504–2513. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Kawamura I, Nomura T, Tsuchiya K, Hara H, Dewamitta SR, et al. Toll-like receptor 2- and MyD88-dependent phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Rac1 activation facilitates the phagocytosis of Listeria monocytogenes by murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 2010;78:2857–2867. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01138-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camejo A, Buchrieser C, Couve E, Carvalho F, Reis O, Ferreira P, et al. In vivo transcriptional profiling of Listeria monocytogenes and mutagenesis identify new virulence factors involved in infection. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000449. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Tian D, Jia Y, Gao Y, Fu H, Niu Z, et al. Attenuated Listeria monocytogenes, a Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESAT-6 antigen expression and delivery vector for inducing an immune response. Res Microbiol. 2012;163:540–549. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraud H, Bronowicki JP.Curative treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma Rev Prat 201363229–233.French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalerba P, Cho RW, Clarke MF. Cancer stem cells: models and concepts. Annu Rev Med. 2007;58:267–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.58.062105.204854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita T, Wang XW. Cancer stem cells in the development of liver cancer. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1911–1918. doi: 10.1172/JCI66024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brundage RA, Smith GA, Camilli A, Theriot JA, Portnoy DA. Expression and phosphorylation of the Listeria monocytogenes ActA protein in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11890–11894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Boland JA, Kocks C, Dramsi S, Ohayon H, Geoffroy C, Mengaud J, et al. Nucleotide sequence of the lecithinase operon of Listeria monocytogenes and possible role of lecithinase in cell-to-cell spread. Infect Immun. 1992;60:219–230. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.1.219-230.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquis H, Doshi V, Portnoy DA. The broad-range phospholipase C and a metalloprotease mediate listeriolysin O-independent escape of Listeria monocytogenes from a primary vacuole in human epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4531–4534. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4531-4534.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y, Yin Y, Duan F, Fu H, Hu M, Gao Y, et al. Prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy of an attenuated Listeria monocytogenes-based vaccine delivering HPV16 E7 in a mouse model. Int J Mol Med. 2012;30:1335–1342. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan ZK, Weiskirch LM, Paterson Y. Regression of established B16F10 melanoma with a recombinant Listeria monocytogenes vaccine. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5264–5269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel FR, Hegde S, Lieberman J, Paterson Y. Induction of cell-mediated immune responses to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein by using Listeria monocytogenes as a live vaccine vector. J Immunol. 1995;155:4775–4782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Castro F, Gonzalez D, Maciag PC, Paterson Y, Gravekamp C. Mage-b vaccine delivered by recombinant Listeria monocytogenes is highly effective against breast cancer metastases. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:741–749. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baecher-Allan C, Viglietta V, Hafler DA. Human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Sem Immunol. 2004;16:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Fu JL, Lu YY, Fu BY, Wang CP, An LJ, et al. Regulatory T cells are associated with post-cryoablation prognosis in patients with hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:968–978. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M, Ramos I, Asafu-Adjei D, Quispe-Tintaya W, Chandra D, Jahangir A, et al. Curcumin improves the therapeutic efficacy of Listeria(at)-Mage-b vaccine in correlation with improved T-cell responses in blood of a triple-negative breast cancer model 4T1. Cancer Med. 2013;2:571–582. doi: 10.1002/cam4.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.