Abstract

The synthetic peptide T-20, which corresponds to a sequence within the C-terminal heptad repeat region (HR2) of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) gp41 envelope glycoprotein, potently inhibits viral membrane fusion and entry. Although T-20 is thought to bind the N-terminal heptad repeat region (HR1) of gp41 and interfere with gp41 conformational changes required for membrane fusion, coreceptor specificity determined by the V3 loop of gp120 strongly influences the sensitivity of HIV-1 variants to T-20. Here, we show that T-20 binds to the gp120 glycoproteins of HIV-1 isolates that utilize CXCR4 as a coreceptor in a manner determined by the sequences of the gp120 V3 loop. T-20 binding to gp120 was enhanced in the presence of soluble CD4. Analysis of T-20 binding to gp120 mutants with variable loop deletions and the reciprocal competition of T-20 and particular anti-gp120 antibodies suggested that T-20 interacts with a gp120 region near the base of the V3 loop. Consistent with the involvement of this region in coreceptor binding, T-20 was able to block the interaction of gp120-CD4 complexes with the CXCR4 coreceptor. These results help to explain the increased sensitivity of CXCR4-specific HIV-1 isolates to the T-20 peptide. Interactions between the gp41 HR2 region and coreceptor-binding regions of gp120 may also play a role in the function of the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) enters target cells through the action of its envelope glycoproteins, gp120 and gp41 (10, 47, 62). The gp120 exterior envelope glycoprotein interacts sequentially with the cellular receptors, CD4 (12, 30, 36), and chemokine receptors (1, 11, 13, 17-19). CD4 binding facilitates virus attachment to the cell surface and mediates conformational changes in gp120 that allow a high-affinity interaction with the chemokine receptor (3, 24, 43, 44, 50, 52, 53, 59). Receptor binding is thought to trigger further conformational changes in the viral envelope glycoprotein that eventually promote the fusion of the viral and target cell membranes by the gp41 transmembrane envelope glycoprotein, allowing entry of the viral core into the host cell cytoplasm (6, 56).

The ectodomain of the gp41 glycoprotein contains a hydrophobic amino terminus, which is thought to insert into the target cell membrane and hence is called the fusion peptide (20, 22, 32), and two heptad repeat regions, HR1 and HR2. HR1 is immediately carboxy terminal to the fusion peptide and can form a trimeric, α-helical coiled coil. The HR2 regions, which are near the viral membrane-spanning region, can form helices that pack into the well-conserved, largely hydrophobic grooves on the outer surface of the HR1 coiled coil (9, 34, 35, 51, 55, 56). The resulting formation of a six-helix bundle structure is believed to approximate the viral and the target cell membranes and eventually drive membrane fusion (10, 21, 46).

Synthetic peptides corresponding to both the HR1 and HR2 helices exhibit the ability to inhibit HIV-1 infection specifically, with the HR2 peptides being more potent (29, 57, 58; S. Jiang, K. Lin, N. Strick, and A. R. Neurath, Letter, Nature 365:113, 1993). One peptide, T-20 (also called DP178), corresponds to a linear 36-amino-acid sequence within HR2 and potently inhibits viral entry and membrane fusion of both laboratory-adapted strains and primary isolates of HIV-1 (29, 58). The structural features of the gp41 six-helix bundle suggest that the T-20 peptide acts through a dominant-negative mechanism, packing into the grooves of the HR1 coiled coil and preventing the natural HR2 region on gp41 from doing so (21, 31). In support of this model, a contiguous 3-amino-acid sequence (GIV) within HR1 was identified to be critical for inhibition of HIV-1 entry by T-20. Substitutions at two positions within the GIV sequence, G to S or D and V to M, conferred resistance to T-20 on HIV-1 (39).

Although HIV-1 can evolve to be resistant to T-20 by altering the GIV motif in gp41, the sequence is well conserved in natural HIV-1 isolates. Recent studies showed that, among naturally occurring HIV-1 variants, coreceptor specificity can strongly influence sensitivity to T-20 (14, 15). Primary isolates that utilize CCR5 for entry (R5 viruses) were found to be more resistant to T-20 than those that utilize CXCR4 (X4 viruses). Moreover, the determinant of coreceptor specificity, the gp120 V3 loop, also modulated this sensitivity to T-20 (14, 15). Studies of viruses with envelope proteins containing alterations of the V3 loop or the bridging sheet, two gp120 regions implicated in coreceptor binding, suggested that gp120-coreceptor affinity correlated with T-20 resistance (38). As increased coreceptor affinity resulted in faster fusion kinetics, a model was proposed in which enhanced coreceptor affinity accelerated the formation of the six-helix bundles, reducing the temporal window during which the envelope glycoproteins are sensitive to T-20 (38).

Here, we report that T-20 interacts with soluble HIV-1 gp140 trimers from X4 or X4R5 strains, but not those from R5 strains. The strain preference of T-20 binding was determined by the gp120 V3 sequence. Surprisingly, T-20 directly interacted with the gp120 glycoprotein of the X4 isolate HXBc2 in a CD4-induced, V3 loop-dependent manner. Furthermore, we found that this T-20-gp120 interaction affected the binding of some antibodies to gp120 and blocked the interaction between gp120-CD4 complexes and the CXCR4 coreceptor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Peptides and recombinant proteins.

T-20 consists of the HR2 region (residues 638 to 673) of the HXBc2 gp41 envelope glycoprotein. The scrambled version of T-20 (scrT-20) has the sequence EKLNENLIQTSWFDYSELAEQNKSHWQILLWESLQE.

The DP178-C9 peptide contains the HR2 region (residues 638 to 673) of the YU2 HIV-1 gp41 glycoprotein fused with a nine-residue peptide (C9) from the cytoplasmic carboxyl terminus of rhodopsin (25). DP178-C9 was synthesized by New England Peptide (Fitchburg, Mass.).

The DP178-immunoglobulin (Ig) expression plasmid was constructed by inserting the sequence corresponding to that of DP178 from the HXBc2 gp41 envelope glycoprotein and a sequence for a GSGSG linker between the NheI and BamHI sites of a plasmid expressing the CD4-Ig protein (5, 45a). Thus, the DP178 sequence and linker are covalently joined to the dimeric Fc portion of an Ig molecule. This soluble DP178-Ig protein was expressed by transfecting the plasmid into 293T cells with GenePorter II reagent (GTS Inc., San Diego, Calif.), and purified from the supernatant by a protein A-Sepharose column. The DP178-Ig protein was demonstrated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) to be ∼95% pure, and it efficiently precipitated radiolabeled soluble gp130(−/GCN4) [s-gp130(−/GCN4)] trimers (68) and exhibited moderate inhibition of single-round HIV-1 entry assays (data not shown).

The C34-Ig fusion protein consists of sequences from residues 628 to 661 of the HXBc2 HIV-1 gp41 glycoprotein linked by the GSGSG sequence to the Fc Ig domain. C34-Ig was produced and purified as described above for DP178-Ig.

Precipitation of HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins.

The sgp140 trimers were produced transiently in 293T cells as previously described (67). Briefly, 293T cells were transfected by using LipofectAMINE Plus (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) with plasmids expressing sgp140 trimers of different HIV-1 strains. The cells were labeled with [35S]methionine for ∼24 h. After cellular debris was cleared by low-speed centrifugation, the sgp140 glycoproteins in 200 μl of radiolabeled supernatant were precipitated by either 1 μl of pooled sera (PS) from HIV-1-infected individuals or 0.5 μg of the synthetic peptide DP178-C9 at 4°C overnight. The proteins were precipitated with either protein A-Sepharose (Pharmacia) or 1D4-Sepharose, respectively, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by autoradiography. The sgp140 bands on the gels were quantified by using a Phosphor Screen and Storm 820 scanner (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.).

The wild-type gp120 protein or gp120 proteins with variable loop deletions were precipitated from 200 μl of supernatant from [35S]methionine-labeled 293T cells by either 1 μl of PS from HIV-1-infected individuals or 1 μg of DP178-Ig. Precipitations were performed in the absence or presence of 2 μg of sCD4/ml at room temperature for 3 h, followed by SDS-PAGE of the precipitated proteins and autoradiography. The experiment was repeated with similar results.

Antibody and DP178/T-20 competition for gp120 binding.

To investigate whether DP178/T-20 binding to gp120 affects the binding of anti-gp120 monoclonal antibodies, an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed with a panel of antibodies that recognize different gp120 epitopes. The HXBc2 gp120 glycoprotein was produced transiently in transfected 293T cells. After cell debris was cleared by low-speed centrifugation, the gp120 glycoproteins in the 293T supernatants were captured on ELISA plates by a sheep antibody (D7324) directed against the carboxyl-terminal 15 amino acid residues of gp120 (Aalto BioReagents, Dublin, Ireland). The effect of T-20 on CD4-gp120 binding was tested by incubating the gp120 on the ELISA plates with various concentrations (0.1, 1, and 10 μg/ml) of CD4-Ig in combination with various concentrations (0, 1, and 10 μg/ml) of pure T-20 peptide (American Peptide Co., Sunnyvale, Calif.), followed by detection with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-human Ig secondary antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and development with 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrates (Sigma). To examine the effect of T-20 on antibody binding, the gp120 glycoproteins captured on the ELISA plates were first incubated with various concentrations (0, 1, and 10 μg/ml) of T-20 peptide in the presence of 2 μg of sCD4/ml and then incubated with various concentrations (0.1, 1, and 10 μg/ml) of antibodies. The antibodies bound to gp120 were detected with HRP-conjugated goat anti-human Ig or goat anti-mouse Ig secondary antibodies, and the assays were developed with TMB substrate.

To examine the effect of anti-gp120 antibodies on the recognition of HIV-1 gp120-sCD4 complexes by the DP178/T-20 peptide, the DP178-Ig fusion protein was biotinylated using Sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin following the instructions of the manufacturer (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). After incubation with radiolabeled HXBc2 gp120 in the presence of sCD4 and either 1 or 10 μg of different monoclonal antibodies/ml, the biotinylated DP178-Ig was precipitated by streptavidin-Sepharose (Pharmacia). The radiolabeled gp120 bound to the streptavidin-Sepharose beads was analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography.

gp120-CXCR4 binding assay.

The effect of T-20 on gp120-CXCR4 interaction was studied with paramagnetic proteoliposomes (PMPLs) containing pure native CXCR4, as previously described (2, 4). The HXBc2 gp120 glycoprotein was purified from the supernatant of transiently expressing 293T cells by affinity chromatography using the F105 anti-gp120 antibody. Approximately 5 × 106 CXCR4 PMPLs in a 100-μl volume were incubated with 1.2 μg (100 nM final concentration) of purified HXBc2 gp120 in the absence or presence of 1 μg of sCD4 for 1 h at room temperature. The gp120 bound to CXCR4 PMPLs was stained with 1 μg of C11 antibody at room temperature for an additional hour, followed by staining with a phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-human Ig secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) at 4°C for 1 h. The stained CXCR4 PMPLs were analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). To examine the effects of T-20 on the interaction of HXBc2 gp120-sCD4 complexes with CXCR4, 1 or 10 μg of T-20 peptide was added during the incubation of gp120, sCD4, and CXCR4 PMPLs, and the binding assay was carried out as described above.

Single-round infection assays.

To examine the inhibitory effect of T-20 or scrT-20 on infection by viruses containing particular HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein variants, a single-round infection assay (68) was employed. Recombinant HIV-1 encoding luciferase and containing various HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins was incubated with either Cf2Th-CD4/CXCR4 or Cf2Th-CD4/CCR5 target cells in the presence of different amounts of T-20 or scrT-20. Cf2Th-CD4/CXCR4 cells were used for viruses with the HXBc2, HXBc2SIM, MN, ADA(MNV3/440), and VSV-G envelope glycoproteins. Cf2Th-CD4/CCR5 cells were used for viruses with the YU2, HX(YUV3), YU2SIM, HX(YUV3)SIM, ADA, and MN(ADAV3) envelope glycoproteins. After 2 days, the luciferase activity in the target cells was measured.

RESULTS

DP178/T-20 recognizes gp140 envelope glycoproteins of CXCR4-using HIV-1 isolates.

The sgp140 trimers used in this study consist of the complete gp120 and gp41 ectodomains and contain alterations in the gp120/gp41 proteolytic cleavage site (arginines at amino acid positions 508 and 511 changed to serines). The lack of proteolytic cleavage prevents the sgp140 glycoproteins from undergoing receptor-induced conformational changes in the HR1 gp41 region (45a). In addition, a GCN4 or fibritin trimeric motif is appended to the carboxyl terminus of the gp41 ectodomain to promote and maintain trimer formation. These proteins have been shown to form almost exclusively trimers when expressed in tissue cultured cell lines (65-67). To test the interaction between these sgp140 glycoproteins and DP178/T-20, a peptide (DP178-C9) consisting of a sequence corresponding to the HR2 region of the YU2 HIV-1 strain (residues 638 to 673) and a 9-amino-acid sequence (C9) from the cytoplasmic carboxyl terminus of rhodopsin (25) was synthesized. The 1D4 antibody (25), which is a murine monoclonal antibody directed against the C9 peptide, was directly coupled to CNBr-activated Sepharose (Pharmacia) according to the manufacturer's instructions. This reagent (designated 1D4-Sepharose) was used to facilitate precipitation of HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins by the DP178-C9 peptide.

The radiolabeled sgp140 trimers were incubated with either PS from HIV-1-infected individuals (Fig. 1A, top) or the DP178-C9 peptide (Fig. 1A, bottom). The proteins were precipitated with either protein A-Sepharose (Pharmacia) or 1D4-Sepharose, respectively, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by autoradiography. As shown in Fig. 1A, the DP178-C9 peptide precipitated the sgp140 glycoproteins of some HIV-1 strains more efficiently than those of other strains. The sgp140 bands on the gels were quantified. The amount of sgp140 glycoproteins precipitated by PS reflects the total sgp140 present in the cell supernatant and thus was used as a standard for determining the percentage of the sgp140 trimers precipitated by the DP178 peptide. Figure 1B demonstrates that the sgp140 trimers from the X4 viruses HXBc2 and P3.2, and from the R5X4 viruses KB9 and 89.6, were recognized by DP178 much more efficiently than those from the R5 viruses YU2, JR-FL, ADA, and ZM651. DP178-C9 precipitation of R5 virus trimers was consistently <2% that of PS, whereas DP178-C9 precipitated >6% of the sgp140 molecules of X4 or R5X4 isolates recognized by PS. The precipitation of X4 or R5X4 HIV-1 sgp140 trimers was not a consequence of recognition by the C9 peptide or 1D4 antibody, because the C9 peptide combined with 1D4-Sepharose failed to precipitate any sgp140 glycoproteins (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Recognition of sgp140 trimers from R5, X4, and R5X4 HIV-1 strains by the DP178 peptide. 293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing sgp140 trimers of different HIV-1 strains and labeled with [35S]methionine. (A) The sgp140 glycoproteins in the radiolabeled supernatant were precipitated by either PS from HIV-1-infected individuals (top) or the synthetic peptide DP178-C9 (bottom). (B) After SDS-PAGE, the proteins were quantified, and the percentages of the sgp140 trimers precipitated by DP178 are shown. In the protein names, -G represents sgp140-GCN4 trimers, and -F represents sgp140-fibritin trimers. The experiments were repeated with similar results.

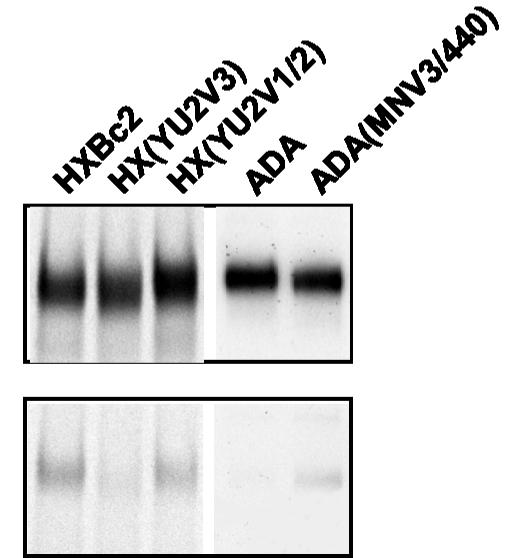

Previous studies demonstrated that DP178/T-20 interacts with HR1 of gp41, which accounts for the peptide's ability to inhibit HIV-1 infection (39, 58); coreceptor specificity, which is determined by the V3 loop of gp120, can modulate viral sensitivity to DP178/T-20 (14, 15). To determine whether the V3 loop sequence of gp120 influences DP178/T-20 binding to the sgp140 trimers, we analyzed chimeric sgp140-GCN4 trimers, in which V1/V2 or V3 loop sequences from an R5 virus, YU2, were inserted into the envelope glycoproteins of an X4 virus, HXBc2. The plasmids expressing these chimerae were constructed by substituting the KpnI (6347)-MfeI (7666) fragment of the corresponding YU2-HXBc2 chimeric gp160 expressors (49) into the HXBc2 sgp140-GCN4 expressor plasmid. These chimeric trimers were produced and analyzed as described above. All of the sgp140 chimeric glycoproteins were expressed efficiently, as determined by PS precipitation (Fig. 2, top). As seen before, the HXBc2 sgp140 trimers interacted with DP178 (Fig. 2, bottom). However, the chimeric sgp140 trimers [HX(YU2V3)] consisting of HXBc2 envelope glycoproteins with the V3 loop derived from the YU2 strain did not bind DP178. The chimera of the HXBc2 envelope glycoproteins with the V1/V2 loop from YU2 [HX(YU2V1/V2)] bound DP178 at a level similar to that of the HXBc2 sgp140 trimers. These results imply that the coreceptor-specific interaction between DP178 and sgp140 trimers is determined by the sequence of the gp120 V3 loop. To examine this in another context, we analyzed another chimera [ADA(MNV3/440)] in which the V3 loop sequence from an X4 HIV-1 strain, MN, was inserted into the sgp140-GCN4 trimer of an R5 strain, ADA. In addition, arginine 440 of the ADA envelope glycoproteins was converted to glutamic acid, which is found in MN gp120. Changes in residue 440 can contribute to the tropism of HIV-1 strains (7). The ADA sgp140 trimer did not detectably bind DP178, but the ADA(MNV3/440) sgp140 trimer exhibited a low level of binding to DP178 (Fig. 2). These results suggest that DP178 binds to soluble gp140 envelope glycoproteins in a manner determined largely by the sequence of the gp120 V3 loop.

FIG. 2.

Recognition of chimeric sgp140 trimers by the DP178 peptide. sgp140-GCN4 trimers from the HXBc2 or ADA HIV-1 strain or chimeric sgp140-GCN4 trimers with V1/2 or V3 loops derived from different coreceptor-specific strains were expressed in 293T cells, which were radiolabeled with [35S]methionine. The cell supernatants were precipitated by either PS from HIV-1-infected individuals (top) or DP178-C9 (bottom) at 4°C overnight. The precipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. HX(YU2V3) is the sgp140-GCN4 trimer of the HXBc2 HIV-1 strain with a V3 region derived from the YU2 strain. HX(YU2V1/2) is the sgp140-GCN4 trimer of the HXBc2 HIV-1 strain with the V1/V2 variable loops derived from the YU2 strain. ADA(MNV3/440) is the sgp140-GCN4 trimer of the ADA strain with residue 440 and the V3 region corresponding in sequence to that of the MN strain.

DP178/T-20 recognition of an X4 HIV-1 gp120 is V3 dependent and CD4 enhanced.

From the panel of different HIV-1 viruses, YU2 and HXBc2 were chosen as examples of R5 and X4 strains, respectively. The gp120 envelope glycoproteins from these two viruses were transiently expressed, radiolabeled, and incubated with DP178-Ig. In the DP178-Ig molecule, the DP178 sequence is covalently linked to the dimeric Fc portion of an Ig molecule. The YU2 gp120 glycoprotein did not detectably interact with DP178-Ig, either in the presence or absence of sCD4 (Fig. 3). By contrast, a small amount of the HXBc2 gp120 glycoprotein was precipitated by DP178-Ig in the absence of sCD4. The DP178-Ig precipitation of the HXBc2 gp120 glycoprotein was markedly enhanced by the presence of sCD4. As YU2 and HXBc2 gp120 glycoproteins bind sCD4 with comparable affinities, the differential precipitation of YU2 and HXBc2 gp120-sCD4 complexes by DP178-Ig indicates that DP178 requires specific sequences on HXBc2 gp120 for recognition.

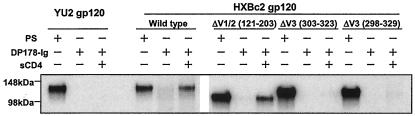

FIG. 3.

Precipitation of gp120 envelope glycoproteins (wild type or with variable loops deleted). The gp120 proteins were precipitated from the supernatants of [35S]methionine-labeled 293T cells by either PS from HIV-1-infected individuals or DP178-Ig. The precipitations were performed in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 2 μg of sCD4/ml at room temperature for 3 h, followed by SDS-PAGE of the precipitated proteins and autoradiography. The experiment was repeated with similar results.

The contribution of the HXBc2 major variable loops to DP178-Ig recognition was investigated. Previous studies showed that HXBc2 gp120 proteins with deletions of the V1/V2 loops [ΔV1/2(121-203)], or the V3 loop [ΔV3(303-323) and ΔV3(298-329)] bound CD4 with roughly comparable affinities (61). The ΔV3(298-329) mutant contains a deletion of the entire V3 loop, whereas the ΔV3(303-323) mutant contains a deletion of the variable tip of the V3 loop, retaining the more conserved residues near the base of the loop (61). Each of these mutants contains a Gly-Ala-Gly linker at the site of the deletion. In the absence of sCD4, these three mutant gp120 proteins were not detectably precipitated by DP178-Ig (Fig. 3). However, in the presence of sCD4, the ΔV1/2(121-203) gp120 mutant was efficiently precipitated by DP178-Ig. By contrast, the gp120 mutants containing the deletions of the V3 loop, either the deletion of the whole loop or the deletion of the variable tip of the loop, did not detectably interact with DP178-Ig in the presence of sCD4 (Fig. 3). Thus, the ability of HXBc2 gp120 to bind DP178 in the presence of CD4 was dependent upon the integrity of the V3 loop but not the V1/V2 loops.

Reciprocal effects of DP178/T-20 and monoclonal antibodies on gp120 binding.

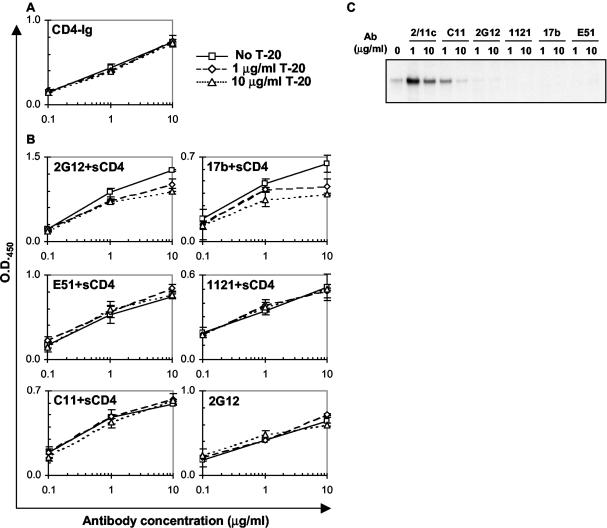

To investigate whether DP178/T-20 binding to gp120 affects the binding of anti-gp120 monoclonal antibodies, an ELISA was performed with a panel of antibodies that recognize different gp120 epitopes. The HXBc2 gp120 glycoprotein was captured on ELISA plates by a sheep antibody (D7324) directed against the gp120 carboxyl terminus. The effect of T-20 on CD4-gp120 binding was first tested by incubating gp120 on the ELISA plates with various concentrations of CD4-Ig in combination with various concentrations of T-20 peptide. Figure 4A shows that the T-20 peptide, at the concentrations tested, did not affect CD4 binding to gp120.

FIG. 4.

Effects of T-20 on antibody binding to HXBc2 gp120. (A and B) HXBc2 gp120 glycoproteins in the supernatant of transiently expressing 293T cells were captured on ELISA plates by a sheep antibody (D7324) against the carboxyl-terminal 15 amino acids of gp120. (A) Bound gp120 glycoproteins were incubated with various concentrations of T-20 peptide and the indicated concentrations of CD4-Ig at room temperature for 1 h. The bound CD4-Ig was detected with an HRP-conjugated anti-Ig secondary antibody and TMB substrates. (B) Bound gp120 glycoproteins were incubated with various concentrations of T-20 peptide in the absence (bottom right) or presence (+sCD4; 2 μg/ml) of sCD4 at room temperature for 1 h, followed by incubation with the indicated concentrations of antibodies at room temperature for another hour. The antibodies bound to gp120 were detected with an HRP-conjugated anti-Ig secondary antibody and TMB substrates. The means and standard deviations of the optical densities at 450 nm (O.D.450) are shown. (C) Radiolabeled HXBc2 gp120 was incubated with sCD4, the indicated amounts of antibodies (Ab), and biotinylated DP178-Ig. Avidin-Sepharose was used for precipitation, and the gp120 bound to the beads was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

To examine the effect of T-20 on antibody binding, the gp120 glycoproteins captured on the ELISA plates were first incubated with various concentrations of T-20 peptide in the presence of 2 μg of sCD4/ml and then incubated with various concentrations of antibodies. The antibodies tested in this study included 2G12, a human antibody recognizing an epitope consisting of glycans on the outer domain of gp120 (42, 45); 17b and E51, two CD4-induced antibodies (37, 63, 64); C11, a human antibody recognizing a discontinuous epitope composed of elements of the C1/C5 regions of gp120 (37); and 1121 (ImmunoDiagnostics, Woburn, Mass.), a mouse antibody recognizing the GPGRA amino acid sequence at the tip of the V3 loop of gp120. Of these antibodies, 2G12 and 17b exhibited mild decreases in binding in the presence of T-20, whereas E51, C11, and 1121 exhibited no significant differences in binding in the presence and absence of peptide (Fig. 4B). For the antibodies that were affected by T-20, the same ELISA was performed without the addition of sCD4. Under these conditions, 2G12 binding to gp120 was not affected by the presence of the T-20 peptide (Fig. 4B, bottom right). This is consistent with the CD4-induced interaction of T-20 with gp120. The binding of the 17b antibody to gp120 in the absence of sCD4 was too low to determine reliably the effects of T-20 on this interaction (data not shown). We conclude that, in the presence of CD4, T-20 can weakly affect the binding of the 2G12 and 17b antibodies to the HXBc2 gp120 glycoprotein.

We also examined the effect of anti-gp120 antibodies on the recognition of HIV-1 gp120-sCD4 complexes by the DP178/T-20 peptide. For this purpose, the DP178-Ig fusion protein was biotinylated. The biotinylated DP178-Ig was incubated with radiolabeled HXBc2 gp120 in the presence of sCD4 and either 1 or 10 μg of different monoclonal antibodies/ml and then precipitated by Avidin-Sepharose. The radiolabeled gp120 bound to the Avidin-Sepharose beads was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by autoradiography (Fig. 4C). The precipitation of the gp120-sCD4 complexes by DP178-Ig was not inhibited, and was even enhanced, by the addition of the 2/11c and C11 antibodies. The 2/11c antibody recognizes a discontinuous gp120 epitope that is determined by the C1 and C4 regions and that is located near the binding sites for CD4 and the CD4i antibodies (37). DP178-Ig precipitation of gp120-sCD4 complexes was inhibited by the 2G12, 1121, 17b, and E51 antibodies. As all of the epitopes for these antibodies share gp120 structures in the V3 loop or the adjacent β19 strand, these results define a localized region on gp120 that is important for T-20 binding.

T-20 interferes with X4 HIV-1 gp120 binding to CXCR4.

The contribution of the gp120 V3 loop and β19 strand to binding both T-20 and the chemokine receptors (4, 23, 27, 28, 40, 41, 48) prompted an examination of the ability of T-20 to interfere with the interaction of gp120/sCD4 complexes with CXCR4. Previous studies demonstrated that the gp120 glycoprotein from CXCR4-using HIV-1 strains binds nonspecifically to several cell lines lacking human CXCR4 expression (2). To circumvent this problem, we performed binding studies with the HXBc2 gp120 glycoprotein and PMPLs containing pure native CXCR4, as previously described (2, 4). Figure 5A shows that the HXBc2 gp120-CXCR4 interaction was CD4 dependent; only very weak binding of gp120 to CXCR4 PMPLs was detected in the absence of sCD4, whereas in the presence of sCD4, HXBc2 gp120 strongly bound to CXCR4 PMPLs. To examine the effects of T-20 on the interaction of HXBc2 gp120-sCD4 complexes with CXCR4, 1 or 10 μg of T-20 peptide was added during the incubation of gp120, sCD4, and CXCR4 PMPLs, and the binding assay was carried out. The addition of 1 μg of T-20 significantly blocked the binding of HXBc2 gp120-sCD4 complexes to CXCR4 (Fig. 5B), as did the addition of 10 μg of T-20 (data not shown). As a control, 1 or 10 μg of the C9 peptide was added to the binding assay, but the peptide did not affect the gp120-CXCR4 interaction (Fig. 5C and data not shown). We conclude that T-20 can bind gp120-sCD4 complexes and block the interaction of gp120 with CXCR4.

FIG. 5.

Effects of T-20 on HXBc2 gp120 binding to CXCR4 PMPLs. CXCR4 PMPLs were incubated with purified HXBc2 gp120 in the absence (black peak) or presence (green and red peaks) of sCD4. Incubation with CXCR4 PMPLs was performed with no added peptide (A), with the addition of 1 μg of the T-20 peptide (B), or with the addition of 10 μg of the C9 peptide (C). The gp120 glycoproteins bound to the CXCR4 PMPLs were detected by FACS analysis, using the C11 antibody followed by a phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-human Ig secondary antibody.

T-20 sequence requirements for gp120 binding.

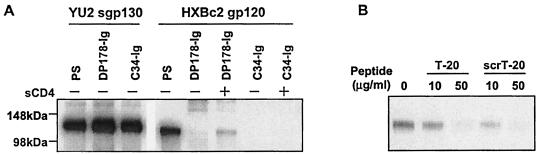

The requirements for specific sequences on the T-20 peptide for binding the gp120 glycoprotein from CXCR4-using HIV-1 isolates were examined. We tested the recognition of the HXBc2 gp120 glycoprotein by the C34 peptide, which is derived from an HIV-1 gp41 segment (residues 628 to 661) that partially overlaps the T-20/DP178 segment. The C34 peptide was expressed as a fusion protein linked by the GSGSG sequence to the Fc Ig domain. Both the C34-Ig and DP178-Ig fusion proteins were able to precipitate the YU2 sgp130(−/GCN4) trimeric glycoprotein, which is missing the entire HR2 region of gp41 and has the HR1 region spontaneously exposed (65, 66) (Fig. 6A). Thus, both proteins exhibit the ability to interact with the HR1 region. However, only DP178-Ig and not C34-Ig precipitated HXBc2 gp120-sCD4 complexes (Fig. 6A). Apparently, sequences in the C-terminal part of the gp41 ectodomain contribute to the ability of peptides derived from this region to bind gp120 from CXCR4-using HIV-1 isolates.

FIG. 6.

Sequence requirements on the T-20/DP178 peptide for gp120 recognition. (A) Radiolabeled YU2 sgp130(−/GCN4) glycoproteins were incubated with PS from HIV-1-infected individuals, DP178-Ig, or C34-Ig and protein A-Sepharose. In parallel, radiolabeled HXBc2 gp120 glycoproteins, in the absence (−) or presence (+) of sCD4, were incubated with PS, DP178-Ig, or C34-Ig. The precipitated proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (B) Radiolabeled HXBc2 gp120 was incubated with DP178-Ig and protein A-Sepharose in the presence of the indicated concentrations of T-20 or scrT-20. The precipitated gp120 glycoprotein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

To examine the sequence requirements for T-20 binding further, the radiolabeled HXBc2 gp120 glycoprotein was incubated with sCD4 and precipitated by DP178-Ig in the presence of either T-20 or scrT-20. Both T-20 and scrT-20 competed for the immunoprecipitation of gp120-sCD4 complexes by DP178-Ig (Fig. 6B). This result indicates that the ability of T-20 to bind gp120 is not strictly dependent upon the linear sequence of the peptide.

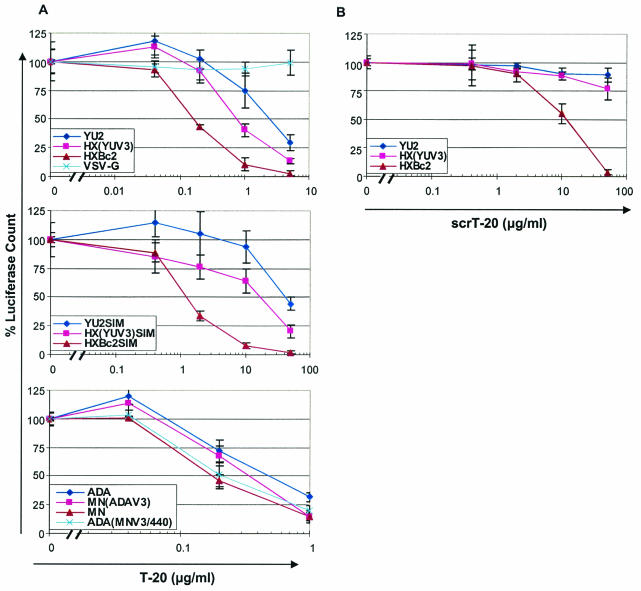

Effects of T-20 and scrT-20 on infection by HIV-1 variants.

To examine the inhibitory effect of T-20 on infection by viruses containing some of the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins used in the binding assays, a single-round infection assay was employed. Recombinant HIV-1 encoding luciferase and containing various HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins was incubated with target cells in the presence of different amounts of T-20. The resulting luciferase activities indicate that viruses with the HXBc2 envelope glycoproteins are more sensitive (50% inhibitory concentration [IC50] = 0.16 μg/ml) than viruses with the YU2 envelope glycoproteins (IC50 = 2.4 μg/ml) (Fig. 7A). Differences in the gp120 V3 loop accounted for part of this observed difference in T-20 sensitivity, as viruses with the HX(YUV3) envelope glycoproteins exhibited an IC50 of 0.74 μg/ml, intermediate between the values associated with the parental viruses.

FIG. 7.

Effects of T-20 or scrT-20 on infection by HIV-1 with different envelope glycoproteins. Recombinant, luciferase-expressing HIV-1 containing the indicated envelope glycoproteins was incubated with target cells in the presence of various concentrations of either T-20 (A) or scrT-20 (B). For each virus, the luciferase activity in the target cells is normalized to the amount observed for the same virus in the absence of peptide. The results shown represent the means and standard deviations determined from two independent experiments.

Alteration of residues 547 to 549 in the gp41 HR1 region has been shown to decrease the sensitivity of HIV-1 to T-20 (14, 15, 39). The sensitivities to T-20 of viruses containing the HXBc2, YU2, and HX(YUV3) envelope glycoproteins with a substitution of Ser-Ile-Met (SIM) for the Gly-Ile-Val sequence at positions 547 to 549 were examined. The observed IC50 values were as follows: HXBc2SIM, 1.7 μg/ml; YU2SIM, 45 μg/ml; and HX(YUV3)SIM, 22.7 μg/ml (Fig. 7A). Thus, as expected, these viruses were more resistant to T-20 inhibition than viruses containing envelope glycoproteins with Gly-Ile-Val at residues 547 to 549. Nonetheless, a pattern of sensitivity similar to that observed for the viruses with wild-type gp41 sequences was apparent. Viruses with HXBc2SIM envelope glycoproteins were more sensitive to T-20 than viruses with the YU2SIM or HX(YUV3)SIM envelope glycoproteins.

The difference in T-20 sensitivity between viruses with the X4 MN envelope glycoproteins (IC50 = 0.18 μg/ml) and viruses with the R5 ADA envelope glycoproteins (IC50 = 0.47 μg/ml) was less than that observed for viruses with the HXBc2 and YU2 envelope glycoproteins. Nonetheless, the gp120 V3 loop was a major determinant of the degree of T-20 resistance. Viruses with the MN (ADAV3) envelope glycoproteins exhibited an IC50 of 0.34 μg/ml, and viruses with the ADA (MNV3/440) envelope glycoproteins were inhibited by T-20 with an IC50 of 0.21 μg/ml, close to that of the viruses with the MN envelope glycoproteins (Fig. 7A). Thus, the sensitivity of viruses to T-20 inhibition exhibits a relationship with the ability of the gp120 glycoprotein to be recognized by T-20, a property determined in large part by the gp120 V3 loop.

The activity of T-20 and other HR2 peptides to inhibit gp41 function is dependent upon the linear sequence of the peptide (29, 47, 57, 58; Jiang et al., Letter). In contrast, the ability of T-20 to bind the gp120 glycoprotein of X4 HIV-1 isolates appears to be less dependent on the linear sequence of the peptide (see above). To examine whether the X4 gp120-binding ability of T-20 contributes to the antiviral activity, infection by viruses with the HXBc2, YU2, or HX(YUV3) envelope glycoprotein was studied in the presence of the scrambled scrT-20 peptide. Infection by viruses with the HXBc2 envelope glycoproteins was inhibited by scrT-20 with an IC50 of 14 μg/ml, whereas scrT-20 exerted little effect on infection by viruses with the YU2 or HX(YUV3) envelope glycoproteins (Fig. 7B). These results are consistent with a contribution of gp120 binding, in a V3 loop-dependent manner, to the antiviral activity of T-20-like peptides.

DISCUSSION

Our data demonstrate that the T-20/DP178 peptide corresponding to the HR2 region of the HIV-1 gp41 glycoprotein specifically interacts with the gp120 glycoproteins of HIV-1 isolates that utilize CXCR4 as a coreceptor. This interaction is enhanced by CD4 binding and is determined by the gp120 V3 sequence. T-20 blocked the interaction of gp120-sCD4 complexes with the CXCR4 coreceptor. Coreceptor binding is a necessary step for the fusion of membranes mediated by the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins (1, 11, 13, 17-19), so interfering with gp120-CXCR4 interaction is expected to inhibit virus infection. For most HIV-1 strains, the dominant-negative effect of HR2-like peptides on the formation of the gp41 six-helix bundle represents the major mechanism of antiviral activity of these peptides (39). However, it has been shown that coreceptor specificity determined by the gp120 V3 loop sequences significantly influences the sensitivity of HIV-1 variants to T-20 (14, 15). Higher concentrations of T-20 were required to inhibit CCR5-using viruses than were needed to block infection by CXCR4-using viruses (14, 15). The coreceptor-binding affinity of CCR5-using isolates is generally greater than that of CXCR4-using isolates (16, 26). Reeves et al. reported that greater gp120-coreceptor affinity correlated with decreased sensitivity to T-20 (38). Increased coreceptor-binding affinity may be associated with faster kinetics of the membrane fusion process, decreasing the temporal window of opportunity for T-20 to bind its target HR1 sequence (38). Our results suggest an additional mechanism whereby the sensitivity of CXCR4-using viruses to T-20 may be increased. CD4 binding forms and exposes the coreceptor-binding site on gp120 and, in addition, results in the creation and/or exposure of the hydrophobic groove on the HR1 coiled coil (8, 54; Si et al., submitted). Thus, in addition to the induction of a T-20-binding site on the gp41 glycoprotein, our study suggests that CD4 binding enhances T-20 binding to the gp120 envelope glycoprotein of R5X4 and X4 HIV-1 isolates. T-20 binding to gp120 interferes with CXCR4 binding and thus could contribute to the increased sensitivity of CXCR4-using HIV-1 isolates to T-20 inhibition.

Our work provides insights into the T-20-binding site on the gp120 glycoprotein of CXCR4-using viruses. T-20 weakly inhibited the binding of two antibodies, 17b and 2G12, to gp120 in the presence of sCD4. In a reciprocal binding experiment, these antibodies, as well as the E51 and 1121 antibodies, diminished the recognition of gp120 by a T-20 construct. The 17b and E51 antibodies are CD4-induced antibodies and recognize the highly conserved β19 strand of gp120 (63, 64). The β19 strand and the adjacent V3 loop are thought to undergo significant conformational changes upon CD4 binding and cooperate to achieve binding to the CXCR4 or CCR5 coreceptor (4, 33, 40, 41, 60). Of interest is the observation that the 2/11c antibody, which can induce the binding of the CD4-induced antibody 17b (37), also enhances T-20 recognition of gp120. These results suggest that the β19 strand of gp120 is near or within the T-20 binding site. The 2G12 antibody recognizes high-mannose glycans on the HIV-1 gp120 outer domain, which include two N-linked carbohydrate chains at asparagines 295 and 332 (42, 45). These gp120 residues reside adjacent to the cysteines that form a disulfide bond at the base of the V3 loop. Thus, the anti-gp120 antibodies that affect or are affected by T-20 all recognize epitopes that include gp120 elements near the base of the V3 loop. The sensitivity of T-20 binding to changes in the V3 loop and the ability of T-20 to interfere with coreceptor interactions is consistent with a T-20-binding site that includes the V3 loop and gp120 regions near the base of this loop.

The differential binding of T-20 to gp120 glycoproteins from CXCR4-using and CCR5-using HIV-1 isolates is determined, at least in part, by the composition of the gp120 V3 loop. The V3 loops of X4 viruses contain more basic residues than those of R5 viruses. For example, V3 loop residues 303 to 323 of the HXBc2 X4 isolate include seven arginines or lysines and no acidic resides, whereas the corresponding region of the YU2 R5 isolate contains three basic and two acidic residues. The charged regions of X4 viruses are clustered along the flanks of the V3 loop and have been shown to contribute to coreceptor choice (4). Although the T-20 conformation that binds gp120 is unknown, it is noteworthy that HR2 peptides can form amphipathic helices with a concentration of acidic residues along one face of the helix. These acidic residues are well conserved among HIV-1 isolates, regardless of coreceptor usage. The possibility that this acidic face of the HR2 peptide forms a cognate binding surface for the basic V3 loop of gp120 from X4 HIV-1 isolates is consistent with our observation that the T-20 peptide from either YU2 or HXBc2 bound X4 virus envelope glycoproteins preferentially. Our observation that a peptide with a composition identical to that of T-20 but with a scrambled sequence apparently retained the ability to bind X4 gp120 glycoproteins is consistent with this binding being mediated by multiple electrostatic contacts. However, it is noteworthy that the C34 peptide, which contains more acidic residues than T-20/DP178, did not detectably bind X4 gp120 glycoproteins. DP178 does contain, at its C terminus, a region extremely rich in Glu, Gln, Asp, and Asn residues, presenting opportunities for the formation of salt bridges and hydrogen bonds with the gp120 glycoprotein. Further work will be required to test this model.

Our results raise the possibility that the natural HR2 region on gp41 interacts with elements of the gp120 glycoprotein, either before receptor binding or during the process of virus entry. Changes in HR2 can affect the noncovalent association between gp120 and gp41 (4a). However, the key elements contributing to gp120-gp41 association would be expected to be similar among HIV-1 isolates with different coreceptor preferences. Alternatively, HR2 interactions with the V3 loop of CXCR4-using isolates could provide a tether for the otherwise flexible variable loop in the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins prior to receptor binding. In this model, CD4 binding might release the V3 loop for chemokine receptor binding and free HR2 for interaction with the HR1 coiled coil. Indeed, CD4 binding to the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins has been reported to lead to increased exposure of the V3 loop and the HR2 region (53), although the importance of these phenomena for virus entry is not yet clear.

After CD4 binding, interactions between the gp41 HR2 region and gp120 might contribute to the entry of X4 viruses. Such interactions might optimally position gp120, the HR2 region, the gp41 six-helix bundle, or the CXCR4 coreceptor for negotiating the process of membrane fusion. Such a process could be more important when gp120-coreceptor binding is relatively weak, as in the case of gp120-CXCR4 interaction (2, 26). Further work will be required to define the role of this intriguing interaction in HIV-1 entry.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephane Basmaciogullari for advice on the preparation of CXCR4 PMPLs and Jianhua Sui for help with FACS analysis. We thank Yvette McLaughlin and Sheri Farnum for manuscript preparation.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI24755, AI39420, and AI41581), the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation, the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, and the late William F. McCarty-Cooper. Z.S. was supported by a pilot project grant from the Dana-Farber-Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center-Children's Hospital Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI28691).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alkhatib, G., C. Combadiere, C. C. Broder, Y. Feng, P. E. Kennedy, P. M. Murphy, and E. A. Berger. 1996. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science 272:1955-1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babcock, G. J., T. Mirzabekov, W. Wojtowicz, and J. Sodroski. 2001. Ligand binding characteristics of CXCR4 incorporated into paramagnetic proteoliposomes. J. Biol. Chem. 276:38433-38440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandres, J. C., Q. F. Wang, J. O'Leary, F. Baleaux, A. Amara, J. A. Hoxie, S. Zolla-Pazner, and M. K. Gorny. 1998. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) envelope binds to CXCR4 independently of CD4, and binding can be enhanced by interaction with soluble CD4 or by HIV envelope deglycosylation. J. Virol. 72:2500-2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basmaciogullari, S., G. J. Babcock, D. Van Ryk, W. Wojtowicz, and J. Sodroski. 2002. Identification of conserved and variable structures in the human immunodeficiency virus gp120 glycoprotein of importance for CXCR4 binding. J. Virol. 76:10791-10800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4a.Cao, J., L. Bergeron, E. Helseth, M. Thali, H. Repke, and J. Sodroski. 1993. Effects of amino acid changes in the extracellular domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 67:2747-2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Capon, D. J., S. M. Chamow, J. Mordenti, S. A. Marsters, T. Gregory, H. Mitsuya, R. A. Byrn, C. Lucas, F. M. Wurm, J. E. Groopman, et al. 1989. Designing CD4 immunoadhesins for AIDS therapy. Nature 337:525-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carr, C. M., C. Chaudhry, and P. S. Kim. 1997. Influenza hemagglutinin is spring-loaded by a metastable native conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:14306-14313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrillo, A., and L. Ratner. 1996. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tropism for T-lymphoid cell lines: role of the V3 loop and C4 envelope determinants. J. Virol. 70:1301-1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan, D. C., C. T. Chutkowski, and P. S. Kim. 1998. Evidence that a prominent cavity in the coiled coil of HIV type 1 gp41 is an attractive drug target. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:15613-15617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan, D. C., D. Fass, J. M. Berger, and P. S. Kim. 1997. Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell 89:263-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan, D. C., and P. S. Kim. 1998. HIV entry and its inhibition. Cell 93:681-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choe, H., M. Farzan, Y. Sun, N. Sullivan, B. Rollins, P. D. Ponath, L. Wu, C. R. Mackay, G. LaRosa, W. Newman, N. Gerard, C. Gerard, and J. Sodroski. 1996. The beta-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell 85:1135-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalgleish, A. G., P. C. Beverley, P. R. Clapham, D. H. Crawford, M. F. Greaves, and R. A. Weiss. 1984. The CD4 (T4) antigen is an essential component of the receptor for the AIDS retrovirus. Nature 312:763-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng, H., R. Liu, W. Ellmeier, S. Choe, D. Unutmaz, M. Burkhart, P. Di Marzio, S. Marmon, R. E. Sutton, C. M. Hill, C. B. Davis, S. C. Peiper, T. J. Schall, D. R. Littman, and N. R. Landau. 1996. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature 381:661-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Derdeyn, C. A., J. M. Decker, J. N. Sfakianos, X. Wu, W. A. O'Brien, L. Ratner, J. C. Kappes, G. M. Shaw, and E. Hunter. 2000. Sensitivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to the fusion inhibitor T-20 is modulated by coreceptor specificity defined by the V3 loop of gp120. J. Virol. 74:8358-8367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Derdeyn, C. A., J. M. Decker, J. N. Sfakianos, Z. Zhang, W. A. O'Brien, L. Ratner, G. M. Shaw, and E. Hunter. 2001. Sensitivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to fusion inhibitors targeted to the gp41 first heptad repeat involves distinct regions of gp41 and is consistently modulated by gp120 interactions with the coreceptor. J. Virol. 75:8605-8614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doranz, B. J., S. S. Baik, and R. W. Doms. 1999. Use of a gp120 binding assay to dissect the requirements and kinetics of human immunodeficiency virus fusion events. J. Virol. 73:10346-10358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doranz, B. J., J. Rucker, Y. Yi, R. J. Smyth, M. Samson, S. C. Peiper, M. Parmentier, R. G. Collman, and R. W. Doms. 1996. A dual-tropic primary HIV-1 isolate that uses fusin and the beta-chemokine receptors CKR-5, CKR-3, and CKR-2b as fusion cofactors. Cell 85:1149-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dragic, T., V. Litwin, G. P. Allaway, S. R. Martin, Y. Huang, K. A. Nagashima, C. Cayanan, P. J. Maddon, R. A. Koup, J. P. Moore, and W. A. Paxton. 1996. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature 381:667-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng, Y., C. C. Broder, P. E. Kennedy, and E. A. Berger. 1996. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science 272:872-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freed, E. O., D. J. Myers, and R. Risser. 1990. Characterization of the fusion domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein gp41. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:4650-4654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furuta, R. A., C. T. Wild, Y. Weng, and C. D. Weiss. 1998. Capture of an early fusion-active conformation of HIV-1 gp41. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5:276-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallaher, W. R. 1987. Detection of a fusion peptide sequence in the transmembrane protein of human immunodeficiency virus. Cell 50:327-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henkel, T., P. Westervelt, and L. Ratner. 1995. HIV-1 V3 envelope sequences required for macrophage infection. AIDS 9:399-401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hill, C. M., H. Deng, D. Unutmaz, V. N. Kewalramani, L. Bastiani, M. K. Gorny, S. Zolla-Pazner, and D. R. Littman. 1997. Envelope glycoproteins from human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 and simian immunodeficiency virus can use human CCR5 as a coreceptor for viral entry and make direct CD4-dependent interactions with this chemokine receptor. J. Virol. 71:6296-6304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hodges, R. S., R. J. Heaton, J. M. Parker, L. Molday, and R. S. Molday. 1988. Antigen-antibody interaction. Synthetic peptides define linear antigenic determinants recognized by monoclonal antibodies directed to the cytoplasmic carboxyl terminus of rhodopsin. J. Biol. Chem. 263:11768-11775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffman, T. L., G. Canziani, L. Jia, J. Rucker, and R. W. Doms. 2000. A biosensor assay for studying ligand-membrane receptor interactions: binding of antibodies and HIV-1 Env to chemokine receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:11215-11220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hung, C. S., N. Vander Heyden, and L. Ratner. 1999. Analysis of the critical domain in the V3 loop of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 involved in CCR5 utilization. J. Virol. 73:8216-8226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hwang, S. S., T. J. Boyle, H. K. Lyerly, and B. R. Cullen. 1991. Identification of the envelope V3 loop as the primary determinant of cell tropism in HIV-1. Science 253:71-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kilby, J. M., S. Hopkins, T. M. Venetta, B. DiMassimo, G. A. Cloud, J. Y. Lee, L. Alldredge, E. Hunter, D. Lambert, D. Bolognesi, T. Matthews, M. R. Johnson, M. A. Nowak, G. M. Shaw, and M. S. Saag. 1998. Potent suppression of HIV-1 replication in humans by T-20, a peptide inhibitor of gp41-mediated virus entry. Nat. Med. 4:1302-1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klatzmann, D., E. Champagne, S. Chamaret, J. Gruest, D. Guetard, T. Hercend, J. C. Gluckman, and L. Montagnier. 1984. T-lymphocyte T4 molecule behaves as the receptor for human retrovirus LAV. Nature 312:767-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kliger, Y., and Y. Shai. 2000. Inhibition of HIV-1 entry before gp41 folds into its fusion-active conformation. J. Mol. Biol. 295:163-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kowalski, M., L. Bergeron, T. Dorfman, W. Haseltine, and J. Sodroski. 1991. Attenuation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cytopathic effect by a mutation affecting the transmembrane envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 65:281-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwong, P. D., R. Wyatt, J. Robinson, R. W. Sweet, J. Sodroski, and W. A. Hendrickson. 1998. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature 393:648-659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu, M., S. C. Blacklow, and P. S. Kim. 1995. A trimeric structural domain of the HIV-1 transmembrane glycoprotein. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2:1075-1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu, M., and P. S. Kim. 1997. A trimeric structural subdomain of the HIV-1 transmembrane glycoprotein. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 15:465-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDougal, J. S., M. S. Kennedy, J. M. Sligh, S. P. Cort, A. Mawle, and J. K. Nicholson. 1986. Binding of HTLV-III/LAV to T4+ T cells by a complex of the 110K viral protein and the T4 molecule. Science 231:382-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore, J. P., and J. Sodroski. 1996. Antibody cross-competition analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 exterior envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 70:1863-1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reeves, J. D., S. A. Gallo, N. Ahmad, J. L. Miamidian, P. E. Harvey, M. Sharron, S. Pohlmann, J. N. Sfakianos, C. A. Derdeyn, R. Blumenthal, E. Hunter, and R. W. Doms. 2002. Sensitivity of HIV-1 to entry inhibitors correlates with envelope/coreceptor affinity, receptor density, and fusion kinetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:16249-16254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rimsky, L. T., D. C. Shugars, and T. J. Matthews. 1998. Determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to gp41-derived inhibitory peptides. J. Virol. 72:986-993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rizzuto, C., and J. Sodroski. 2000. Fine definition of a conserved CCR5-binding region on the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein 120. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 16:741-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rizzuto, C. D., R. Wyatt, N. Hernandez-Ramos, Y. Sun, P. D. Kwong, W. A. Hendrickson, and J. Sodroski. 1998. A conserved HIV gp120 glycoprotein structure involved in chemokine receptor binding. Science 280:1949-1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanders, R. W., M. Venturi, L. Schiffner, R. Kalyanaraman, H. Katinger, K. O. Lloyd, P. D. Kwong, and J. P. Moore. 2002. The mannose-dependent epitope for neutralizing antibody 2G12 on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein gp120. J. Virol. 76:7293-7305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sattentau, Q. J., and J. P. Moore. 1991. Conformational changes induced in the human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein by soluble CD4 binding. J. Exp. Med. 174:407-415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sattentau, Q. J., J. P. Moore, F. Vignaux, F. Traincard, and P. Poignard. 1993. Conformational changes induced in the envelope glycoproteins of the human and simian immunodeficiency viruses by soluble receptor binding. J. Virol. 67:7383-7393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scanlan, C. N., R. Pantophlet, M. R. Wormald, E. Ollmann Saphire, R. Stanfield, I. A. Wilson, H. Katinger, R. A. Dwek, P. M. Rudd, and D. R. Burton. 2002. The broadly neutralizing anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody 2G12 recognizes a cluster of α1→2 mannose residues on the outer face of gp120. J. Virol. 76:7306-7321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45a.Si, Z., N. Madani, J. M. Cox, J. J. Chruma, J. C. Klein, A. Schorn, N. Phan, L. Wang, A. C. Biorn, S. Cocklin, I. Chaiken, E. Freire, A. B. I. Smith, and J. Sodroski. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Skehel, J. J., and D. C. Wiley. 1998. Coiled coils in both intracellular vesicle and viral membrane fusion. Cell 95:871-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sodroski, J. G. 1999. HIV-1 entry inhibitors in the side pocket. Cell 99:243-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Speck, R. F., K. Wehrly, E. J. Platt, R. E. Atchison, I. F. Charo, D. Kabat, B. Chesebro, and M. A. Goldsmith. 1997. Selective employment of chemokine receptors as human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coreceptors determined by individual amino acids within the envelope V3 loop. J. Virol. 71:7136-7139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sullivan, N., Y. Sun, J. Binley, J. Lee, C. F. Barbas III, P. W. Parren, D. R. Burton, and J. Sodroski. 1998. Determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein activation by soluble CD4 and monoclonal antibodies. J. Virol. 72:6332-6338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sullivan, N., Y. Sun, Q. Sattentau, M. Thali, D. Wu, G. Denisova, J. Gershoni, J. Robinson, J. Moore, and J. Sodroski. 1998. CD4-induced conformational changes in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 glycoprotein: consequences for virus entry and neutralization. J. Virol. 72:4694-4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tan, K., J. Liu, J. Wang, S. Shen, and M. Lu. 1997. Atomic structure of a thermostable subdomain of HIV-1 gp41. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:12303-12308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thali, M., J. P. Moore, C. Furman, M. Charles, D. D. Ho, J. Robinson, and J. Sodroski. 1993. Characterization of conserved human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 neutralization epitopes exposed upon gp120-CD4 binding. J. Virol. 67:3978-3988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trkola, A., T. Dragic, J. Arthos, J. M. Binley, W. C. Olson, G. P. Allaway, C. Cheng-Mayer, J. Robinson, P. J. Maddon, and J. P. Moore. 1996. CD4-dependent, antibody-sensitive interactions between HIV-1 and its co-receptor CCR-5. Nature 384:184-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weiss, C. D., S. W. Barnett, N. Cacalano, N. Killeen, D. R. Littman, and J. M. White. 1996. Studies of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein-mediated fusion using a simple fluorescence assay. AIDS 10:241-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weissenhorn, W., A. Dessen, S. C. Harrison, J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1997. Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature 387:426-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weissenhorn, W., S. A. Wharton, L. J. Calder, P. L. Earl, B. Moss, E. Aliprandis, J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1996. The ectodomain of HIV-1 env subunit gp41 forms a soluble, alpha-helical, rod-like oligomer in the absence of gp120 and the N-terminal fusion peptide. EMBO J. 15:1507-1514. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wild, C., T. Oas, C. McDanal, D. Bolognesi, and T. Matthews. 1992. A synthetic peptide inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus replication: correlation between solution structure and viral inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:10537-10541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wild, C. T., D. C. Shugars, T. K. Greenwell, C. B. McDanal, and T. J. Matthews. 1994. Peptides corresponding to a predictive alpha-helical domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 are potent inhibitors of virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:9770-9774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu, L., N. P. Gerard, R. Wyatt, H. Choe, C. Parolin, N. Ruffing, A. Borsetti, A. A. Cardoso, E. Desjardin, W. Newman, C. Gerard, and J. Sodroski. 1996. CD4-induced interaction of primary HIV-1 gp120 glycoproteins with the chemokine receptor CCR-5. Nature 384:179-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wyatt, R., P. D. Kwong, E. Desjardins, R. W. Sweet, J. Robinson, W. A. Hendrickson, and J. G. Sodroski. 1998. The antigenic structure of the HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein. Nature 393:705-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wyatt, R., J. Moore, M. Accola, E. Desjardin, J. Robinson, and J. Sodroski. 1995. Involvement of the V1/V2 variable loop structure in the exposure of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 epitopes induced by receptor binding. J. Virol. 69:5723-5733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wyatt, R., and J. Sodroski. 1998. The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: fusogens, antigens, and immunogens. Science 280:1884-1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xiang, S. H., N. Doka, R. K. Choudhary, J. Sodroski, and J. E. Robinson. 2002. Characterization of CD4-induced epitopes on the HIV type 1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein recognized by neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 18:1207-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xiang, S. H., L. Wang, M. Abreu, C. C. Huang, P. Kwong, E. Rosenberg, J. E. Robinson, and J. Sodroski. 2003. Epitope mapping and characterization of a novel CD4-induced human monoclonal antibody capable of neutralizing primary HIV-1 strains. Virology 315:124-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang, X., M. Farzan, R. Wyatt, and J. Sodroski. 2000. Characterization of stable, soluble trimers containing complete ectodomains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins. J. Virol. 74:5716-5725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang, X., L. Florin, M. Farzan, P. Kolchinsky, P. D. Kwong, J. Sodroski, and R. Wyatt. 2000. Modifications that stabilize human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein trimers in solution. J. Virol. 74:4746-4754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang, X., J. Lee, E. M. Mahony, P. D. Kwong, R. Wyatt, and J. Sodroski. 2002. Highly stable trimers formed by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins fused with the trimeric motif of T4 bacteriophage fibritin. J. Virol. 76:4634-4642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang, X., R. Wyatt, and J. Sodroski. 2001. Improved elicitation of neutralizing antibodies against primary human immunodeficiency viruses by soluble stabilized envelope glycoprotein trimers. J. Virol. 75:1165-1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]