Abstract

Recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors based on serotype 8 (AAV8) transduce liver with superior tropism following intravenous (IV) administration. Previous studies conducted by our lab demonstrated that AAV8-mediated transfer of the human low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) gene driven by a strong liver-specific promoter (thyroxin-binding globulin [TBG]) leads to high level and persistent gene expression in the liver. The approach proved efficacious in reducing plasma cholesterol levels and resulted in the regression of atherosclerotic lesions in a murine model of homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (hoFH). Prior to advancing this vector, called AAV8.TBG.hLDLR, to the clinic, we set out to investigate vector biodistribution in an hoFH mouse model following IV vector administration to assess the safety profile of this investigational agent. Although AAV genomes were present in all organs at all time points tested (up to 180 days), vector genomes were sequestered mainly in the liver, which contained levels of vector 3 logs higher than that found in other organs. In both sexes, the level of AAV genomes gradually declined and appeared to stabilize 90 days post vector administration in most organs although vector genomes remained high in liver. Vector loads in the circulating blood were high and close to those in liver at the early time point (day 3) but rapidly decreased to a level close to the limit of quantification of the assay. The results of this vector biodistribution study further support a proposed clinical trial to evaluate AAV8 gene therapy for hoFH patients.

Introduction

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is a rare autosomal dominant disorder caused by a mutation in the gene encoding low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) which plays a critical role in lipid metabolism. The prevalence of heterozygous FH patients that inherit one abnormal allele in most populations is 1 in 500. Patients heterozygous for LDLR mutations have elevated levels of LDL and suffer from premature coronary artery disease (CAD; Brown and Goldstein, 1986; Goldstein and Brown, 1989). Homozygous FH (HoFH) patients carrying LDLR mutations in both alleles have severe hypercholesterolemia and life-threatening CAD, with conditions that cannot be managed by conventional therapies. Alternative treatments that include repeated purging of LDL from the blood through the use of plasma exchange or LDL apheresis show limited effectiveness in blocking progression of atherosclerotic lesions (Apstein et al., 1978; Yokoyama et al., 1985; Thompson et al., 1989). The most effective treatment of hoFH has been orthotopic liver transplantation; however, this approach is greatly restricted by the availability of donor tissues and associated morbidity and mortality (Bilheimer et al., 1984; Hoeg et al., 1987). Two pharmacologic treatments for hoFH were recently approved, though neither cure the disease (Akdim et al., 2011; Cuchel et al., 2013).

Adeno-associated virus (AAV)-based vectors have proven to be effective vehicles for efficient and stable gene delivery with broad tropism in vivo. The European Union has recently approved the first gene therapy product, Alipogene (Glybera), based on AAV serotype 1 (AAV1) for patients with lipoprotein lipase deficiency. Clinical trials utilizing AAV serotype 8 (AAV8) vectors as a gene therapy for hemophilia B are ongoing, with the vector proven to be well tolerated, safe, and effective (Nathwani et al., 2011). We developed an AAV8-based gene replacement therapy targeting liver, the primary organ responsible for regulating cholesterol homeostasis, to treat hoFH patients. AAV8, with its lower sero-prevalence and incidence of pre-existing neutralizing antibodies in humans compared with AAV2 (Calcedo et al., 2009), as well as its superior tropism for liver is the serotype of choice for liver-directed gene delivery (Wang et al., 2010a, 2010b). Based on results from extensive preclinical studies by our group (Kassim et al., 2010, 2013), we demonstrated that gene delivery mediated by AAV8 encoding wild-type human LDLR under the control of a liver-specific promoter, thyroxin-binding globulin (TBG), can lead to long-term vector-derived LDLR expression and can effectively reduce and reverse hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerotic plaque formation in a murine model of FH (Powell-Braxton et al., 1998; double knockout [DKO] mouse, LDLR−/−, Apobec−/−) following intravenous (IV) administration. Based on encouraging results from preclinical studies, we selected AAV8.TBG.hLDLR as the candidate to be evaluated in a clinical trial for gene replacement therapy in hoFH patients. Results presented here are from a nonclinical vector biodistribution study using AAV8.TBG.hLDLR in a mouse model of hoFH conducted as part of safety assessment studies to support an FH clinical trial application.

Results and Discussion

Clinical trial

We propose an AAV8.TBG.hLDLR-based phase I clinical trial of gene therapy in hoFH patients. The design will be a single ascending dose design with half-log increases in AAV dose and a formal safety assessment of each cohort prior to dose escalation. The trial will involve two cohorts (N=3/cohort), with each cohort receiving a different dose of vector administered via a peripheral vein with the initial dose of AAV8.TBG.hLDLR to be 1.0×1012 genome copies (GC)/kg. Six weeks after the third subject has been dosed, a formal review of all safety data will be performed. According to predetermined criteria, if safety is deemed adequate, the second dose group will be initiated at a dose of 3×1012 GC/kg (1/2 log unit higher than the first dose). A similar safety review will occur at 6 weeks after the final subject is dosed.

HoFH subjects will be withdrawn from LDL apheresis and/or plasma exchange apheresis for at least 1 month prior to vector administration. Subjects will be admitted to a research inpatient unit for a baseline LDL kinetic study followed by vector administration. The clinical candidate, AAV8.TBG.hLDLR vector, will be administered via a peripheral vein by slow bolus administration. Vital signs will be monitored frequently for 24 hr. Blood will be drawn for safety testing daily for 3 days, then weekly for 2 weeks, then monthly for up to 3 months. Subjects will be re-admitted for a repeat LDL kinetic study at 3 months, after which they will be permitted to resume apheresis therapy. Subjects will have a safety visit with blood draw every 3 months up to 1 year, and will be followed every 6 months by telephone calls thereafter up to 5 years.

The primary endpoint will be a detailed safety assessment. A key secondary endpoint will be LDL cholesterol reduction at 3 months. A key tertiary endpoint will be the change in fractional catabolic rate of LDL apoB from baseline to 3 months after vector administration.

Objectives and study design

The goal of this study is to evaluate the initial biodistribution, clearance, and persistence of AAV8.TBG.hLDLR following IV administration in a murine model of hoFH. Mice carrying a mutation in the LDLR gene (LDLR−/−) were first engineered as a disease model for FH studies (Sanan et al., 1998). Although a deficiency in LDLR in humans leads to pronounced hypercholesterolemia and myocardial infarction, deletion of the LDLR gene in the mouse is not associated with hypercholesterolemia when the animals are fed a normal chow diet (Sanan et al., 1998; Daugherty, 2002). It is possible to induce hypercholesterolemia in the LDLR−/− mouse through a high-fat diet; however, the lipoprotein profile and the pathology of atherosclerosis in the mouse model does not recapitulate that seen in humans. A potential reason for the phenotypic difference in LDLR deficiency between mouse and man is attributed to the difference in metabolism of apolipoprotein B (ApoB; Rader and FitzGerald, 1998). Humans synthesize the full-length version of ApoB called ApoB100, which is incorporated into LDL particles rendering them high-affinity ligands for LDLR. Mice express high levels of the ApoB mRNA editing catalytic polypeptide-1 (Apobec1) in the liver, which results in the production of a truncated form of the ApoB protein called ApoB48 that does not bind to the LDLR. ApoB48 is cleared more rapidly from the blood through processes that are independent of the LDLR, possibly explaining why LDLR−/− mice do not develop significant hypercholesterolemia or atherosclerosis on a normal chow diet (Rohlmann et al., 1998). In order to create a mouse model with lipoprotein metabolism closely modeling that in humans, DKO mice deficient in both apobec1 and LDLR were subsequently generated (Powell-Braxton et al., 1998). These DKO mice develop severe hypercholesterolemia when on a normal chow diet due to elevations in LDL associated with atherosclerosis that are similar in distribution and histology to that seen in human hoFH patients.

Gene therapy targeting the liver, the major organ for lipoprotein metabolism, was initially developed for hoFH using an ex vivo approach in which autologous hepatocytes were harvested from patients, plated in culture, genetically corrected with recombinant retroviruses encoding wild-type LDLR, and subsequently reintroduced into the patients (Grossman et al., 1994, 1995). Although the procedure was well tolerated, the impact on cholesterol metabolism was modest and variable due to the limited number of cells that were transduced with the retroviral vectors. A change in focus to an in vivo gene delivery approach was made possible due to the discovery of a family of novel AAV serotypes, including serotype 8, which confers superior liver tropism and transduces hepatocytes with high efficiency in vivo (Wang et al., 2010b). Proof-of-concept gene transfer studies, utilizing AAV8 expressing the LDLR gene under the control of the liver-specific TBG promoter, which focused on minimizing the potential immune-mediated elimination of vector-transduced hepatocytes in DKO mice, demonstrated long-term decline of the cholesterol levels and significant reduction in the development of atherosclerosis. Further studies demonstrated that intravenous injection of AAV8.TBG.hLDLR leads to dramatic regression of advanced lesions in the DKO mouse (Kassim et al., 2010, 2013). Based on the promising results from AAV8.TBG.hLDLR-based gene transfer studies in DKO mice, we propose AAV8.TBG.hLDLR as the clinical candidate to be tested in a gene therapy clinical trial for hoFH patients.

In the current study, vector biodistribution was assessed following intravenous administration of a single high dose of AAV vector in the DKO mouse model. This study was performed in a nonbiased manner adhering to standard operating procedures that were developed by the Gene Therapy Program at the University of Pennsylvania and reviewed by Quality Assurance. While parts of this study adhered to Good Laboratory Practices (GLP), the vector was not made under Good Manufacturing Practice conditions, and therefore, the study was not GLP compliant. Appropriate record keeping and documentation of all data were maintained throughout the study. Quality assurance measures and a reporting process were incorporated into the study to ensure the conduct of studies and resulting data are of sufficient quality and integrity to support the proposed clinical trial.

Male and female DKO mice aged 1–6 months were randomized and grouped into 12 cohorts (Table 1) with a group size of five (vector treated) or three (vehicle control) animals per sex per time point. Vector genome biodistribution was examined at day 3, 14, 90, and 180 post gene delivery, key time points identified in the distribution and persistence profile of AAV8 following systemic tail vein administration. Critical to the success of gene therapy is the demonstration of efficacy at doses of vector that are safe and can be easily manufactured. We set to determine the minimal effective dose (MED) that shows some metabolic/clinical effect. For this study, MED was defined as the lowest dose of vector that leads to a statistically significant and stable deduction of total cholesterol in the serum. Our studies in mice that were dosed with vector, the titer of which was determined by a less sensitive routine quantification assay, indicated an MED equal to 1.5×1011 GC/kg (Kassim et al., 2010). We did not see toxicity in mice up to the maximum dose we could administer, which was equal to 6×1013 GC/kg. However, titer of the vector used in this study was determined by an improved validated assay with higher sensitivity. The results indicate that historical vector titers based on our previous routine method were consistently underrepresented by a factor of two- to threefold in comparison to the titers determined by the improved quantification assay. Therefore, our revised MED in mice was 3.75×1011 GC/kg (with a conversion factor of 2.5), and the maximum dose to be administered without toxicity was 1.25×1014 GC/kg. Based on these data, we proposed a dose escalation strategy for the clinical trial beginning at 1×1012 GC/kg, which is 2.5-fold higher than the MED in mice. We would escalate the dose to 3×1012 GC/kg, which is the highest we can currently produce. For the biodistribution study, a single dose of 7.5×1012 GC/kg, 2.5-fold of the intended highest dose of the clinical product AAV8.TBG.hLDLR was administered. In addition to blood, the organs listed in Table 2 were harvested using sterile techniques to avoid potential cross-contamination between different tissue samples. The distribution of vector genomes in these organs was determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis of total cell DNA using primer/probe sets specific to vector sequences. For each tissue sample, three reactions were conducted, including a reaction with a spike of control plasmid DNA of known copy number and identical vector sequence for assessing reaction efficiency and the potential for sample-specific interference. The assay was validated with a detection sensitivity of 50 copies per microgram of genomic DNA with a 95% confidence interval. See Supplementary Information section for more details on the assay parameters and acceptance criteria (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/humc). Data were excluded from the following analysis if the spike-in reaction failed to pass the assay acceptance criteria established during the process of assay validation.

Table 1.

Study Design

| No. of animals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group no. | Dose | Test articles | Male | Female | Time of necropsy (day) |

| 1 | 7.5×1012 GC/kg | AAV8.TBG.hLDLR | 5 | 5 | 3 |

| 2 | 7.5×1012 GC/kg | AAV8.TBG.hLDLR | 5 | 5 | 14 |

| 3 | 7.5×1012 GC/kg | AAV8.TBG.hLDLR | 5 | 5 | 90 |

| 4 | 7.5×1012 GC/kg | AAV8.TBG.hLDLR | 5 | 5 | 180 |

| 5 | 0.2 mL | PBS vehicle control | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 6 | 0.2 mL | PBS vehicle control | 3 | 3 | 14 |

| 7 | 0.2 mL | PBS vehicle control | 3 | 3 | 90 |

| 8 | 0.2 mL | PBS vehicle control | 3 | 3 | 180 |

GC, genome copies; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Table 2.

Order of Tissues Harvested for Biodistribution

| 1 | Blood |

| 2 | Lymph node (inguinal)a |

| 3 | Salivary glanda |

| 4 | Lymph node (lumbar)a |

| 5 | Gonad (testis or ovary) |

| 6 | Pancreas |

| 7 | Spleen |

| 8 | Kidney (left) |

| 9 | Median liver lobe |

| 10 | Left liver lobe |

| 11 | Lung |

| 12 | Aortaa |

| 13 | Heart |

| 14 | Esophagusa |

| 15 | Stomacha |

| 16 | Small intestine |

| 17 | Large intestine |

| 18 | Gastrocnemius muscle |

| 19 | Bone (tibia) |

| 20 | Brain (cerebrum) |

Indicates that samples prepared from these tissues were excluded from analysis due to significant assay interference.

Summary of data

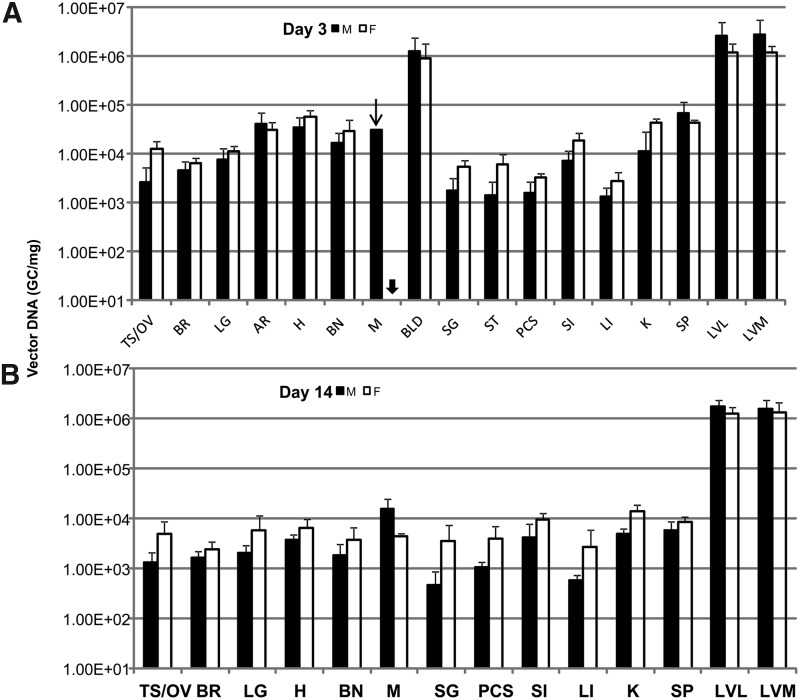

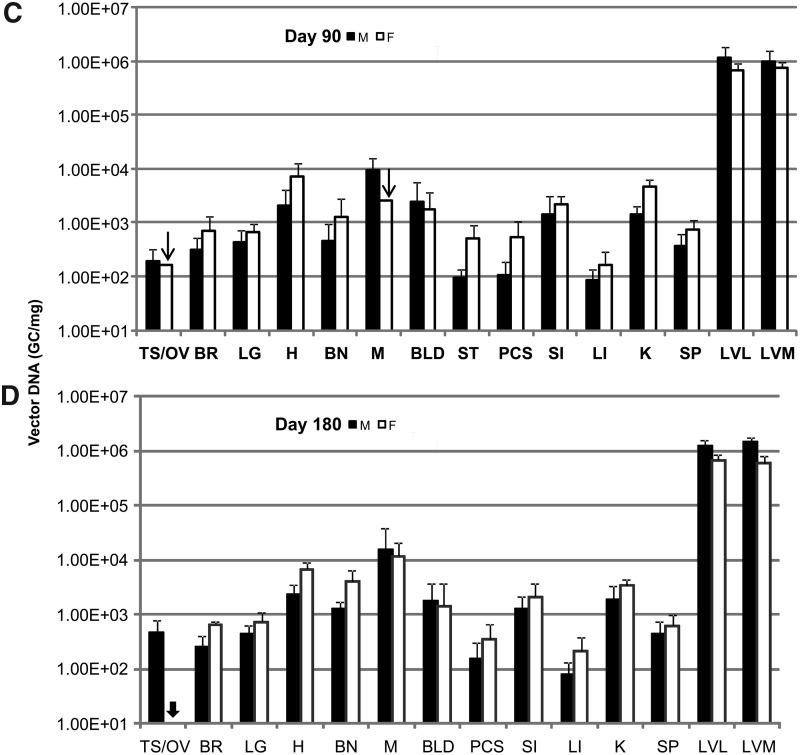

The majority of samples passed the acceptance criteria, although some prepared from lymph nodes (inguinal and lumbar), salivary gland, aorta, esophagus, and stomach were excluded due to significant assay interference as indicated in Table 2. The negative control samples from mice receiving PBS injection all had undetectable levels or levels below the limit of quantification of the assay except in two samples possibly due to cross-contamination. In addition, results from one assay were excluded due to detectable levels of AAV DNA found in the column flow-through control (DNA preparation without tissues). The results of AAV DNA detection in tissues from mice receiving vectors are summarized in Fig. 1, which shows a comparison between sexes at each time point, and Fig. 2, which shows genome copy numbers as a function of time.

FIG. 1.

Biodistribution of adeno-associated virus (AAV) genomic DNA in double knockout (DKO) mice following intravenous injection of AAV8.TBG.hLDLR. A high dose (7.5×1012 GC/kg) of AAV was administered by tail vein injection, and the indicated tissues harvested, total DNA prepared, and AAV DNA quantified by TaqMan PCR analysis. The results are shown comparing vector genome copy number in male (black bar) and female mice (white bar, n=5) of which tissues collected at day 3 (A), day 14 (B), day 90 (C), or day 180 (D) following gene transfer. The arrow indicates that only results from two tissue samples out of five tested pass assay acceptance criteria. The arrow head indicates that results from all five samples from the entire group did not pass assay acceptance criteria. Data are shown as mean±SD.

FIG. 2.

Time course of biodistribution of AAV genomic DNA in DKO mice following intravenous injection of AAV8.TBG.hLDLR. The results comparing AAV DNA copy number detected in male (A) or female (B) mice over the study time course. All symbols correspondingly represent those in Fig. 1.

The results clearly indicate that AAV genome could be detected in all organs harvested at all time points tested, although it was sequestered mainly in the liver, the intended target organ. The vector genome copy number in liver was more than 3 logs over that detected in other tissues for all time points. In liver, there was no significant difference between male or female mice at day 3, 14, or 90. However, vector genomes were slightly decreased in female versus male liver at day 180 (one-way ANOVA, Supplementary Fig. S1). The copy number of AAV genomes in liver decreased from 6–14 copies/diploid genome at day 3 to 3–6 copies/diploid genome at day 90 post vector administration and stabilized afterwards. A similar trend of decline was observed in all tissues. The decline in vector copy number was more rapid in tissues with higher cell turnover rate such as blood, large intestine, and spleen, while relatively consistent in muscle (Supplementary Fig. S2). It was noted that the initial rapid decline and persistence of vector genomes in blood indicated that only a low percentage of vector was associated with cells in blood. Furthermore, results from a previous study indicate biologically active AAV vector genomes are detected only in serum for 48–72 hr, suggesting that the risk of horizontal transmission is limited to a short period of time post-injection (Stone et al., 2008). Low, but detectable, levels of AAV genome were also found in the brain harvested at all time points; however, the cell types transduced remain unclear.

In this study, we observed low-level vector in the gonads of both sexes with a gradual reduction but nonetheless persistent level at the end of the experiment (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S3). Although it is beyond the scope of this study to identify the cell types in the gonads that carry vector genomes persistently, reports from previous preclinical and clinical studies could shed some light on this issue. In the hemophilia B clinical trial with intramuscular injection as the route of AAV2 gene delivery, there was no evidence of vector shedding to the semen in adult men or in experimental animal hemophilia B models (Manno et al., 2003; Haurigot et al., 2010). In contrast, the delivery of AAV2 to the liver via the hepatic artery resulted in transient vector dissemination in the semen that eventually disappeared in all patients (Manno et al., 2006). Subsequent studies in rabbit models following intravascular injection of AAV2 or AAV8 concluded that vector dissemination to the semen is dependent on dose and time course and appears to be transient with no evidence of germ line transmission (Schuettrumpf et al., 2006; Favaro et al., 2009). Furthermore, the kinetics of clearance are also dose dependent and vary between serotypes (Favaro et al., 2011). A separate study in mice indicated that there is no evidence of germ line transmission following AAV gene delivery. The offspring from mouse sperm infused with AAV2 and produced by in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer did not carry detectable levels of AAV genomes, indicating AAV2 is not integrated in the germ cell (Couto et al., 2004). Results from a similar study also demonstrated that no inadvertent germ line transmission of AAV genomes was observed after breeding AAV8 IV injected female mice with an untreated male (Paneda et al., 2009). Based on these results, there is no evidence to suggest that recombinant AAV8 can be transferred via germ line transmission, although vector genomes are present persistently in ovary or testis following gene delivery.

Conclusion

Based on the vector biodistribution data presented in this report, it is clear that efficient and prolonged gene transfer to liver is achievable with AAV8 following intravascular administration. The persistence of transgene expression in the liver mediated by AAV8 supports the clinical application of AAV8 gene therapy for treatment of hoFH patients since long-term gene transfer is required to effectively control hypercholesterolemia and the progression of atherosclerotic lesions. In addition, use of the liver-specific promoter TBG to limit transgene expression to the target tissue can further minimize potentially undesired toxicity or host immune responses derived from overexpression of the transgene outside the liver since AAV vector genomes are widely distributed in other tissues at a low level. Our results support further investigation of AAV8.TBG.hLDLR as a potential clinical candidate for gene therapy of hoFH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work was funded by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute P01 HL59407 (J.M.W.).

Author Disclosure Statement

J.M.W. is a consultant to ReGenX Holdings and is a founder of, holds equity in, and receives a grant from affiliates of ReGenX Holdings; in addition, he is an inventor on patents licensed to various biopharmaceutical companies, including affiliates of ReGenX Holdings.

References

- Akdim F., Tribble D.L., Flaim J.D., et al. (2011). Efficacy of apolipoprotein B synthesis inhibition in subjects with mild-to-moderate hyperlipidaemia. Eur. Heart J. 32, 2650–2659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apstein C.S., Zilversmit D.B., Lees R.S., and George P.K. (1978). Effect of intessive plasmapheresis on the plasma cholesterol concentration with familial hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis 31, 105–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilheimer D.W., Goldstein J.L., Grundy S.M., et al. (1984). Liver transplantation to provide low-density-lipoprotein receptors and lower plasma cholesterol in a child with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 311, 1658–1664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M.S., and Goldstein J.L. (1986). A receptor-mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science 232, 34–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcedo R., Vandenberghe L.H., Gao G., et al. (2009). Worldwide epidemiology of neutralizing antibodies to adeno-associated viruses. J. Infect. Dis. 199, 381–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couto L., Parker A., and Gordon J.W. (2004). Direct exposure of mouse spermatozoa to very high concentrations of a serotype-2 adeno-associated virus gene therapy vector fails to lead to germ cell transduction. Hum. Gene Ther. 15, 287–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuchel M., Meagher E.A., du Toit Theron H., et al. (2013). Efficacy and safety of a microsomal triglyceride transfer protein inhibitor in patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: a single-arm, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 381, 40–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty A. (2002). Mouse models of atherosclerosis. Am. J. Med. Sci. 323, 3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favaro P., Downey H.D., Zhou J.S., et al. (2009). Host and vector-dependent effects on the risk of germline transmission of AAV vectors. Mol. Ther. 17, 1022–1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favaro P., Finn J.D., Siner J.I., et al. (2011). Safety of liver gene transfer following peripheral intravascular delivery of adeno-associated virus (AAV)-5 and AAV-6 in a large animal model. Hum. Gene Ther. 22, 843–852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein J.L., and Brown J.C. (1989). Familial hypercholesterolemia, lipoprotein and lipid metabolism disorders. In Metabolic Basis of Inherited Disease II. Scriver C.R., ed. (McGraw-Hill, New York: ) pp.1215–1250 [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M., Raper S.E., Kozarsky K., et al. (1994). Successful ex vivo gene therapy directed to liver in a patient with familial hypercholesterolaemia. Nat. Genet. 6, 335–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M., Rader D.J., Muller D.W., et al. (1995). A pilot study of ex vivo gene therapy for homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia. Nat. Med. 1, 1148–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haurigot V., Mingozzi F., Buchlis G., et al. (2010). Safety of AAV factor IX peripheral transvenular gene delivery to muscle in hemophilia B dogs. Mol. Ther. 18, 1318–1329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeg J.M., Starzl T.E., Brewer H.B., Jr., (1987). Liver transplantation for treatment of cardiovascular disease: comparison with medication and plasma exchange in homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Am. J. Cardiol. 59, 705–707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassim S.H., Li H., Vandenberghe L.H., et al. (2010). Gene therapy in a humanized mouse model of familial hypercholesterolemia leads to marked regression of atherosclerosis. PLoS One 5, e13424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassim S.H., Li H., Bell P., et al. (2013). Adeno-associated virus serotype 8 gene therapy leads to significant lowering of plasma cholesterol levels in humanized mouse models of homozygous and heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Hum. Gene Ther. 24, 19–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manno C.S., Chew A.J., Hutchison S., et al. (2003). AAV-mediated factor IX gene transfer to skeletal muscle in patients with severe hemophilia B. Blood 101, 2963–2972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manno C.S., Pierce G.F., Arruda V.R., et al. (2006). Successful transduction of liver in hemophilia by AAV-Factor IX and limitations imposed by the host immune response. Nat. Med. 12, 342–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathwani A.C., Tuddenham E.G., Rangarajan S., et al. (2011). Adenovirus-associated virus vector-mediated gene transfer in hemophilia B. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 2357–2365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paneda A., Vanrell L., Mauleon I., et al. (2009). Effect of adeno-associated virus serotype and genomic structure on liver transduction and biodistribution in mice of both genders. Hum. Gene Ther. 20, 908–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell-Braxton L., Veniant M., Latvala R.D., et al. (1998). A mouse model of human familial hypercholesterolemia: markedly elevated low density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and severe atherosclerosis on a low-fat chow diet. Nat. Med. 4, 934–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rader D.J., and FitzGerald G.A. (1998). State of the art: atherosclerosis in a limited edition. Nat. Med. 4, 899–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlmann A., Gotthardt M., Hammer R.E., and Herz J. (1998). Inducible inactivation of hepatic LRP gene by cre-mediated recombination confirms role of LRP in clearance of chylomicron remnants. J. Clin. Invest. 101, 689–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanan D.A., Newland D.L., Tao R., et al. (1998). Low density lipoprotein receptor-negative mice expressing human apolipoprotein B-100 develop complex atherosclerotic lesions on a chow diet: no accentuation by apolipoprotein(a). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95, 4544–4549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuettrumpf J., Liu J.H., Couto L.B., et al. (2006). Inadvertent germline transmission of AAV2 vector: findings in a rabbit model correlate with those in a human clinical trial. Mol. Ther. 13, 1064–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone D., Liu Y., Li Z.Y., et al. (2008). Biodistribution and safety profile of recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 6 vectors following intravenous delivery. J. Virol. 82, 7711–7715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson G.R., Barbir M., Okabayashi K., et al. (1989). Plasmapheresis in familial hypercholesterolemia. Arteriosclerosis 9, I152–157 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Calcedo R., Wang H., et al. (2010a). The pleiotropic effects of natural AAV infections on liver-directed gene transfer in macaques. Mol. Ther. 18, 126–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Wang H., Bell P., et al. (2010b). Systematic evaluation of AAV vectors for liver directed gene transfer in murine models. Mol. Ther. 18, 118–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama S., Hayashi R., Satani M., and Yamamoto A. (1985). Selective removal of low density lipoprotein by plasmapheresis in familial hypercholesterolemia. Arteriosclerosis 5, 613–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.