Abstract

Animal colors play important roles in communication, ecological interactions and speciation. Carotenoid pigments are responsible for many yellow, orange and red hues in animals. Whereas extensive knowledge on the proximate mechanisms underlying carotenoid coloration in birds has led to testable hypotheses on avian color evolution and signaling, much less is known about the expression of carotenoid coloration in fishes. Here, we promote cichlid fishes (Perciformes: Cichlidae) as a system in which to study the physiological and evolutionary significance of carotenoids. Cichlids include some of the best examples of adaptive radiation and color pattern diversification in vertebrates. In this paper, we examine fitness correlates of carotenoid pigmentation in cichlids and review hypotheses regarding the signal content of carotenoid-based ornaments. Carotenoid-based coloration is influenced by diet and body condition and is positively related to mating success and social dominance. Gaps in our knowledge are discussed in the last part of this review, particularly in the understanding of carotenoid metabolism pathways and the genetics of carotenoid coloration. We suggest that carotenoid metabolism and transport are important proximate mechanisms responsible for individual and population-differences in cichlid coloration that may ultimately contribute to diversification and speciation.

Keywords: Pigment, Trade-off, Antioxidant, Signal, Cichlidae

1. Introduction

Carotenoids are an important class of pigments in animals. Vertebrates cannot synthesize carotenoids endogenously, but dietary carotenoids derived from photosynthetic organisms are responsible for red, orange and yellow hues of many species, including teleost fishes (Fox and Vevers, 1960; Goodwin, 1984; Kodric-Brown, 1998). In the integument, carotenoid pigments are stored in xanthophores and erythrophores (yellow and red pigment cells, respectively). In fishes and other poikilothermic vertebrates, these types of chromatophores can also synthesize yellow to red pteridine pigments (Braasch et al., 2007). In addition to their role in body coloration, carotenoids have important roles in vision, as precursors of transcription regulators, as antioxidants, and in the immune system (Bendich and Olson, 1989; von Schantz et al., 1999; McGraw and Ardia, 2003; Hill and Johnson, 2012). The size and hue of pigmented tissues are often subject to natural and sexual selection (Grether et al., 2004), and can be important traits in speciation (Boughman, 2002; Maan et al., 2006a). The role of body color in speciation is especially important in animals with acute color vision, such as birds and fishes.

Cichlid fishes (Perciformes: Cichlidae), a group of teleosts endemic to both the Old and New World, provide an excellent system in which to test hypotheses regarding coloration and speciation. Among the Old World cichlids of East Africa, which represent some of the most explosive adaptive radiations among vertebrates (Meyer, 1993; Kocher, 2004), body coloration is inextricably linked with diversification. Color patterns of cichlids diverge in sympatry as well as in allopatry, in response to both natural and sexual selection. In many species, mate choice and dominance interactions are profoundly affected by coloration (Maan and Sefc, 2013), and individuals use dynamic color patterns to communicate motivation and status in social and sexual contexts (Nelissen, 1976; Baerends et al., 1986). Some of these color patterns are carotenoid-based, and in other cases the pigments have yet to be identified. In this review we will (i) briefly introduce the hypotheses that address the signaling function of carotenoid ornaments, (ii) summarize our current understanding of the fitness benefits as well as the biochemical and genetic basis of carotenoid-based coloration in cichlids, and (iii) describe future avenues of research with respect to the role of carotenoids in cichlid coloration and evolution.

2. Carotenoid coloration in signaling

The display of carotenoid-based body coloration is costly. It requires the intake of sufficient amounts of carotenoids from the diet, diverts ingested carotenoids away from vital physiological processes to ornamentation, and makes its bearer conspicuous to predators (Endler, 1980; Lozano, 1994). Consequently, carotenoid-based coloration is believed to constitute an honest, condition-dependent signal with functions in both sexual and social contexts (Olson and Owens, 1998; Svensson and Wong, 2011).

Carotenoids are part of the antioxidant arsenal of animals. Antioxidants quench the potentially harmful pro-oxidant molecules generated during normal metabolism. Oxidative stress arises when the balance between antioxidants and pro-oxidants is disturbed, which can be due to a deficiency of antioxidants or to a surplus of pro-oxidants produced by processes such as somatic growth or an immune response. Animals employ a variety of endogenously produced and food-derived antioxidant compounds, including pigments, vitamins, enzymes and other proteins, and the different compounds can interact with and compensate for each other. Apart from their role as antioxidants, carotenoids may also enhance the immune system through increased T-cell activation, macrophage capacity and lymphocyte proliferation (Bendich and Olson, 1989; Pérez-Rodríguez, 2009).

An influential hypothesis regarding carotenoids posits that trade-offs arise from the dual use of carotenoids for physiological functions and ornamentation (Lozano, 1994; von Schantz et al., 1999; Lozano, 2001). The “carotenoid trade-off hypothesis” suggests that competing physiological demands for carotenoid pigments for immunity and oxidative protection may increase the cost of carotenoid allocation to the skin (McGraw and Ardia, 2003; Clotfelter et al., 2007; Peters, 2007; Alonso-Alvarez et al., 2008; Vinkler and Albrecht, 2010; Svensson and Wong, 2011). This scenario requires that carotenoids are in limited supply in the natural diet (Hill, 1992), an assumption that has not found unanimous approval (Hudon, 1994) and lacks empirical evidence (Hill and Johnson, 2012). However, there is considerable support for two predictions of the carotenoid trade-off hypothesis (reviewed in Blount and McGraw, 2008; Svensson and Wong, 2011). The first is that carotenoid supplementation increases coloration, immunity and/or antioxidant capacity (Hill et al., 2002; Blount et al., 2003; Clotfelter et al., 2007). The second is that immune challenges, which also cause oxidative stress, cause re-allocation of carotenoids and reduce coloration of carotenoid-pigmented structures (Perez-Rodriguez et al., 2010; Toomey et al., 2010).

In the past decade, the importance of carotenoids as in vivo antioxidants has been questioned (Costantini and Møller, 2008; Pérez-Rodríguez, 2009). Hartley and Kennedy (2004) suggested that carotenoids themselves are particularly vulnerable to oxidative damage, and that carotenoid-based ornamentation is therefore an honest indicator of the antioxidant capacity of other, non-pigment molecules such as vitamin E, rather than itself being traded against antioxidant defense. This hypothesis has become known as the “protection hypothesis” (Pérez et al., 2008) because the non-pigment antioxidants protect the carotenoids from oxidation. A related hypothesis, termed the “sparing hypothesis” (Svensson and Wong, 2011), posits that non-pigment antioxidants may protect carotenoids from oxidation (similar to the protection hypothesis), but that carotenoids are still important components of the antioxidant arsenal. The presence of non-pigment carotenoids (again, such as vitamin E) allows the animal to “spare” carotenoids for re-allocation to other functions such as coloration.

While these hypotheses focus on the availability of, and competition for, antioxidant resources, Hill and Johnson (2012) concentrate on the efficiency of cellular processes, which simultaneously control carotenoid coloration, vitamin A homeostasis and redox balance (“shared pathways,” Hill, 2011). In their view, carotenoid coloration signals body condition by reflecting how well such cellular processes are functioning. Physiological models of shared pathways were developed from bird data (Hill and Johnson, 2012; Johnson and Hill, 2013), and although some metabolic pathways and the tissues in which they occur are different in fish (Katsuyama and Matsuno, 1988), the concept may in principle apply to cichlids and other fishes as well.

Another potential clue to the signal value of carotenoid coloration is its connection to glucocorticoid hormones, which are released during the stress response. Glucocorticoids can increase oxidative stress (Costantini et al., 2008) and cause the reallocation of resources to self-maintenance (Bonier et al., 2009). In spite of this, however, positive correlations between glucocorticoids and redness have been reported in lizards (Fitze et al., 2009), fish (Backström et al., 2014) and birds (McGraw et al., 2011; Fairhurst et al., 2014; Lendvai et al., 2013). However, the relationship between stress hormone levels and carotenoid coloration appears to be condition-dependent, constraining the positive correlation to individuals in good condition (Loiseau et al., 2008; Cote et al., 2010). It is possible that only high-quality animals can tolerate high glucocorticoid levels, and thus advertise this ability through their carotenoid coloration. Additionally, the relationship between glucocorticoids and coloration may depend on the net effect of ornament expression on fitness (Candolin, 2000; Cote et al., 2010). Fairhurst et al. (2014) predict that a correlation between coloration and glucocorticoids will exist only when color signals are key to reproductive success, with its direction dependent on the individual's ability to cope with the energetic demands of ornament production.

The alternatives to the carotenoid trade-off hypothesis are based on the assumption that carotenoids are not the currency in which signaling costs are paid. Experimentally discriminating among the different hypotheses is not easily accomplished. The frequently reported effects of immune challenges and antioxidant supplementation on pigmentation are compatible with the traditional trade-off hypothesis as well as with its more recent alternatives (Svensson and Wong, 2011; Hill and Johnson, 2012). So far, the few studies that unambiguously support or contradict one hypothesis do not converge on a common solution. Several recent reviews (Pérez-Rodríguez, 2009; Metcalfe and Alonso-Alvarez, 2010; Svensson and Wong, 2011; Hill and Johnson, 2012) articulate the need for more experiments specifically designed to differentiate among hypotheses, and for more basic information regarding carotenoid availability in nature and the physiological processes involving carotenoids and their derivatives.

3. Carotenoids and fitness in cichlids

In many New and Old World cichlids, carotenoid coloration is correlated with indirect measures of fitness, such as low parasite load, high social status and mate preference. For example, the carotenoid-based red coloration displayed by male Pundamilia nyererei in Lake Victoria, Africa, correlates with their natural parasite loads, experimental antibody responses and oxidative stress levels (Maan et al., 2006b; Dijkstra et al., 2007, 2011). Consequently, females may use the carotenoid coloration to size up the health and vigor of their prospective mates and indeed they prefer more red males over less red males (Maan et al., 2004). Color-based female mate choice also underlies reproductive isolation from a sympatric blue-colored species P. pundamilia (Seehausen and van Alphen, 1998). Furthermore, male–male aggression biases between the two species are based on body color in a frequency-dependent manner (Dijkstra and Groothuis, 2011). The nuptial coloration of P. pundamilia contains substantially fewer carotenoids than that of red P. nyererei (Maan et al., 2008). In tests of the carotenoid trade-off hypothesis in these closely related species, the red P. nyererei males suffered higher oxidative stress and lower immunity in response to social stress than did the blue P. pundamilia males (Dijkstra et al., 2011). In territorial competition under laboratory conditions, however, the red P. nyererei males were more aggressive and socially dominant over blue P. pundamilia males (Dijkstra et al., 2005, 2006, 2009, 2011). The co-existence of territorial males of the two species in the same microhabitat may be facilitated by a balance between the elevated physiological costs associated with the carotenoid-rich male nuptial coloration of P. nyererei and their advantages in intrasexual territorial competition (Dijkstra et al., 2011).

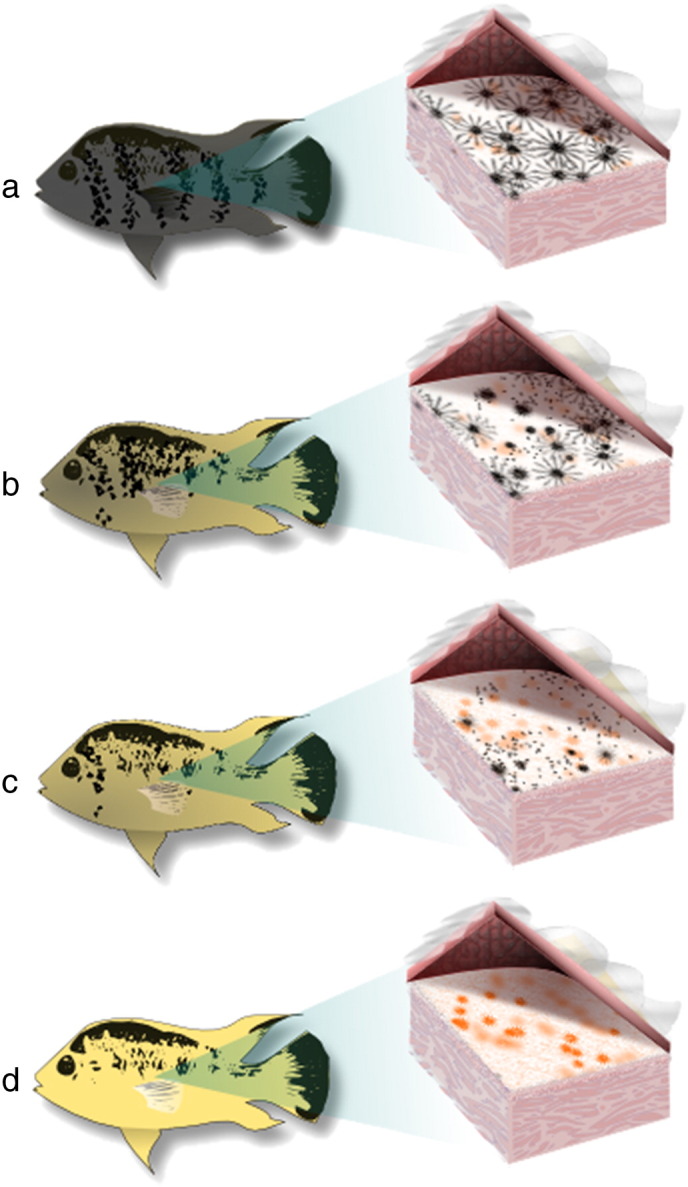

Contrary to the findings in Pundamilia, the trade-off hypothesis received no support in a New World cichlid, the Midas cichlid Amphilophus citrinellus. All Midas cichlids begin life with cryptic gray coloration. As they grow, a minority (8–10%) adopt a distinctive yellow or orange coloration (“gold” morph; Barlow, 1973; Fig. 1). The transition from gray to gold coloration occurs due to the death of the overlying melanophores and accumulation of additional carotenoids in the skin (Dickmann et al., 1988; Fig. 1). Integument carotenoid concentrations, primarily canthaxanthin and tunaxanthin (ε, ε-carotene), are significantly higher in the gold morph than in the gray morph (Webber et al., 1973; Lin et al., 2010). However, contrary to predictions of the carotenoid trade-off hypothesis, dietary supplementation of carotenoids failed to affect skin coloration and did not enhance innate immunity in either morph (Lin et al., 2010). Similarly, findings in female-ornamented convict cichlids Amatitlania siquia and A. nigrofasciata were contrary to the trade-off, protection and sparing hypotheses. Bacteria-challenged fish experienced reduced oxidative stress while simultaneously allocating more carotenoids to integument, particularly in fish maintained on a trace-carotenoid diet (Brown, 2014). This result suggests that fish can mobilize carotenoids from long-term storage in tissues such as the liver in response to a parasite infection, and calls into question whether carotenoids are limited, which is a central assumption of the carotenoid trade-off hypothesis. Furthermore, subsequent analysis of convict cichlid stomach contents in the field did not support the hypothesis that dietary carotenoids are limited under natural conditions (Brown, 2014).

Fig. 1.

Color polymorphism in the Central American Midas cichlid Amphilophus citrinellus. All fish begin life as gray morphs (a). Some fish undergo a color change that involves the dual processes of death of the overlying melanophores and carotenoid deposition in the underlying chromatophores (b–c), resulting in a gold color morph (d). Illustration by Alexandria C. Brown.

Social dominance of red or yellow individuals occurs in several cichlid species (Barlow, 1973; Evans and Norris, 1996; Korzan and Fernald, 2007) as well as in other taxa (e.g., Pryke, 2009). Color-based social dominance is apparent in the firemouth cichlid Thorichthys (formerly Cichlasoma) meeki. Fish fed a high-carotenoid diet were more likely to win in dyadic interactions against fish maintained on a low-carotenoid diet (Evans and Norris, 1996). Importantly, this effect disappeared under green light, when the red coloration was no longer visible. Likewise, in Pundamilia cichlids, the red male advantage disappeared and staged contests lasted longer when skin pigmentation was obscured by green light (Dijkstra et al., 2005), suggesting that the bright red body color normally has an intimidating effect on blue opponents. The association between carotenoid-based color and social status also occurs in the Midas cichlid. Gold animals are more socially dominant than gray animals. The dominance of gold morphs over equally sized gray morphs results in significantly higher growth rates in gold morphs (Barlow, 1973, 1983). The coloration and larger size of gold morphs inhibit aggression by gray morphs, though gold morphs themselves are not intrinsically more aggressive (Barlow and Wallach, 1976; Barlow and McKaye, 1982). Thus, as in the case of Thorichthys (formerly Cichlasoma) meeki and Pundamilia, aggressive advantage may be affected by the perception of carotenoid-based coloration by potential rivals. Dominance of red males also occurs in staged contests between allopatric color morphs of the Lake Tanganyika endemic Tropheus moorii (Sefc et al., in review).

Female carotenoid coloration likewise affects competitive interactions (Beeching et al., 1998; Dijkstra et al., 2009). The convict cichlids A. nigrofasciata and A. siquia (Brown et al., 2013a, 2013b) are reverse-dichromatic; females have a yellow–orange ventrolateral patch that males of this species lack. The function of this carotenoid-pigmented patch is not entirely clear, but laboratory-based experiments suggest that bright coloration incites aggressive responses from other females (Beeching et al., 1998). In a field study, Anderson et al. (in review) observed that female convict cichlids decreased in ventrolateral coloration through the reproductive cycle and with increasing numbers of interactions with predators and heterospecific competitors. Those authors suggest that stress and energy expenditure cause re-absorption of carotenoids from the integument, thus reducing the expression of orange coloration (R.L. Earley, pers. comm.).

Carotenoids have also been detected in the so-called egg spots of several species of Haplochromini and Tropheini cichlids (K.M. Sefc, unpublished data). Egg spots are yellow or orange spots on the anal fins, and are an important synapomorphy in the particularly species-rich haplochromines, a clade of maternal mouthbrooding cichlids comprising the species flocks of Lake Malawi and Lake Victoria (Salzburger et al., 2005). The conspicuousness of the egg spots and their resemblance to the large eggs of the mouthbrooding haplochromine cichlids prompted various hypotheses regarding their role in mate choice, fertilization and reproductive isolation (reviewed in Maan and Sefc, 2013). Recent experiments demonstrated that the effect of egg spots on female choice and male–male aggression varies between species: a female preference for egg spots was detected in Pseudocrenilabrus multicolor (Egger et al., 2011), while in Astatotilapia burtoni eggs spots affected male–male aggression but not mate choice (Theis et al., 2012). Experiments using computer-animated images revealed a sensory bias for yellow, orange or red spots in female haplochromines, including the most ancestral members of the group (Egger et al., 2011), which could represent a proximate mechanism for the observed effects of egg spots on sexual or social interactions.

4. Proximate mechanisms underlying carotenoid coloration

4.1. Specification and spatial arrangement of pigment cells

The differentiation of skin pigment cell types from a common precursor, and their migration to and spatial arrangement within the integument, are under genetic control. Zebrafish and medaka mutants have played a major role in the identification of these ‘pigment’ genes (Rawls et al., 2001; Kelsh, 2004; Kelsh et al., 2009; Braasch and Liedtke, 2011; Yamanaka and Kondo, 2014). In zebrafish, for instance, the transcription factor Pax3 is required for the specification of xanthophores, the pigment cells in which carotenoids are stored (Minchin and Hughes, 2008), and xanthophore migration depends on the receptor tyrosine kinase csf1r (Parichy et al., 2000). The expression of the cichlid paralog csf1ra in yellow-colored egg spots on the anal fins of Haplochromini cichlids (see below) and in the yellow tips of elongated ventral fins in Ectodini cichlids might be associated with xanthophore recruitment into these tissues (Salzburger et al., 2007). The gene csf1ra was also expressed in the yellow areas of the dorsal fin of the cichlids A. burtoni and P. multicolor (Salzburger et al., 2007). In zebrafish, csfr1 expressed in xanthophores also contributes to the spatial organization of melanophores in their vicinity (Parichy, 2006), demonstrating how interactions among different chromatophore lineages influence color pattern formation (Kelsh et al., 2009; Yamanaka and Kondo, 2014).

4.2. Carotenoid uptake and metabolism

Carotenoids ingested by vertebrates include carotene isomers, which are pure hydrocarbons, and oxygenated carotenoids such as lutein, zeaxanthin and astaxanthin (von Lintig, 2010). Following ingestion, carotenoids are absorbed via diffusion or receptor-mediated transport (von Lintig, 2010; Reboul and Borel, 2011). Dietary lipids may increase carotenoid absorption from the intestinal lumen in mammals (Yonekura and Nagao, 2007), though diet studies in carotenoid-ornamented convict cichlids (Brown, 2014) and lizards (San-Jose et al., 2012) showed that additional lipids decreased body color. Once absorbed, carotenoids are enzymatically modified by conversion or esterification/de-esterification, and transported to the liver and target tissues (e.g. the integument) via lipoprotein transporters. In some fishes, including several cichlids, integumentary carotenoids occur both in free and esterified form (Crozier, 1967; Katsuyama and Matsuno, 1988; Wedekind et al., 1998; Hudon et al., 2003; Lin et al., 2010; Brown et al., 2013b; K. M. Sefc, unpublished data). To date, the types of carotenoids identified in cichlid integument include α- and β-carotene, tunaxanthin, canthaxanthin, astaxanthin, lutein, zeaxanthin, rhodoxanthin, and ‘canary-xanthophyll’ B (Webber et al., 1973; Katsuyama and Matsuno, 1988; Lin et al., 2010; Brown et al., 2013a).

In the aquaculture industry there is considerable interest in the dietary assimilation of carotenoids in economically important fishes, including cichlids cultivated for consumption (e.g. Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus) and for the ornamental fish trade. Several studies have shown that dietary supplementation increases the integument concentration of carotenoids in cichlids, but effects were not observed in all species and depended on the types of carotenoids that were added (Katsuyama and Matsuno, 1988; Harpaz and Padowicz, 2007; Kop and Durmaz, 2008; Kop et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2010; Güroy et al., 2012; Brown et al., 2013a; Yilmaz et al., 2013). In some cases, the administration of a carotenoid-rich diet also improved growth rates and enhanced reproductive performance (Güroy et al., 2012; Yilmaz et al., 2013; but see Harpaz and Padowicz, 2007; Pan and Chien, 2009). The effects of dietary carotenoids (predominantly astaxanthin) on coloration, growth and performance are consistent with the putative links between carotenoid signals, health and condition. Discrimination between the alternative hypotheses, however, will require further, specifically designed experiments.

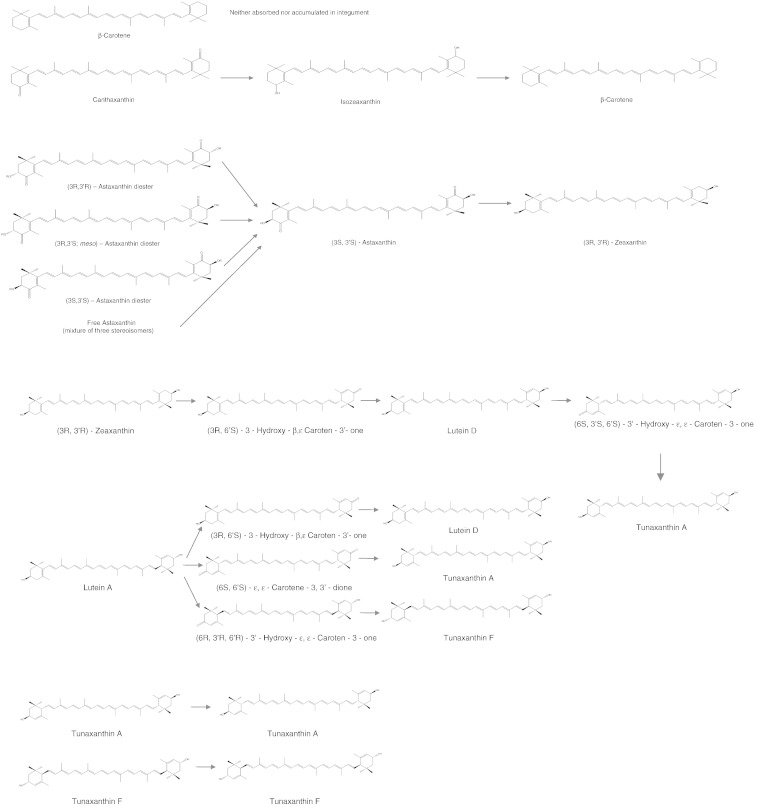

Most of what is known about carotenoid metabolism in the cichlid integument comes from feeding experiments with Nile tilapia (Katsuyama et al., 1987; Katsuyama and Matsuno, 1988). The reconstructed metabolic pathways involve epimerization, reduction or oxidation of dietary canthaxanthin, astaxanthin, zeaxanthin and lutein (Fig. 2). Dietary tunaxanthin accumulated in the integument unchanged, whereas dietary β-carotene was neither accumulated nor bioconverted in the integument (Katsuyama and Matsuno, 1988; Fig. 2). It is unclear to what extent the pathways identified in tilapia are conserved across cichlid species. Consistent with the findings in tilapia, dietary β-carotene had smaller effects on body coloration than astaxanthin in feeding experiments with A. citrinellus (formerly Cichlasoma citrinellum; Pan and Chien, 2009) and Heros severus (formerly Cichlasoma severum; Kop and Durmaz, 2008). The positive correlation between dietary and integumentary astaxanthin concentrations suggests direct deposition of astaxanthin in A. citrinellus (Pan and Chien, 2009).

Fig. 2.

Putative metabolic pathways of carotenoids in the integument of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis nilotica). Additional conversion takes place in the liver (not shown). Metabolic pathways in other cichlid species are virtually unknown, highlighting an area in need of further research. Re-drawn with permission from Katsuyama and Matsuno (1988).

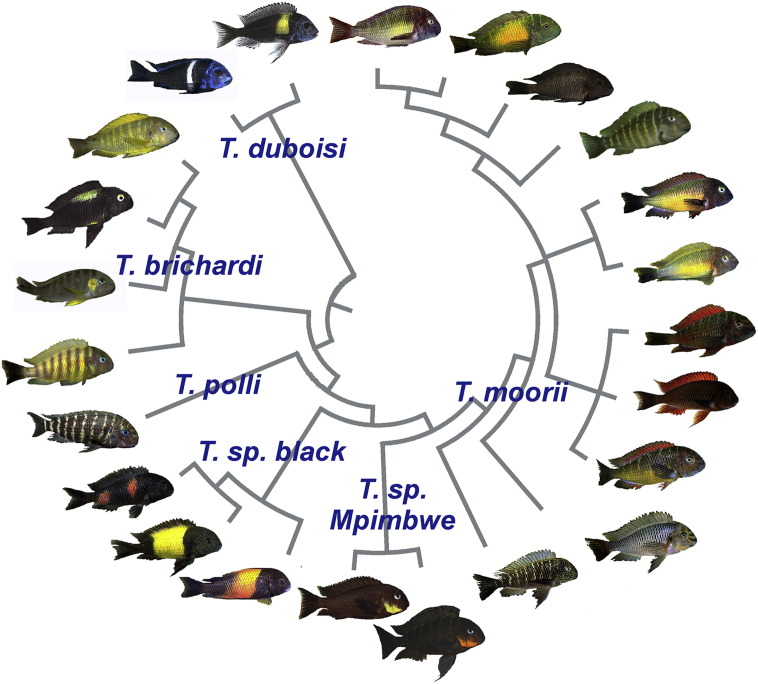

Knowledge of the mechanisms that control the amount and type of carotenoids deposited in integument is prerequisite to understanding the proximate causes of carotenoid color variation. Studies in birds have shown that variation in carotenoid-based coloration can simply reflect presence or absence of carotenoids in the tissue (Eriksson et al., 2008; Walsh et al., 2012), or be caused by differences in carotenoid types (Brush and Seifried, 1968), concentrations (Brush, 1970; Inouye et al., 2001) or both (Crozier, 1967; Hudon et al., 1989). For example, T. moorii populations (Fig. 3) differ not only in total carotenoid content but also in the types of integumentary carotenoids, the latter inferred from the shapes of carotenoid absorption spectra and patterns of HPLC chromatograms (Mattersdorfer et al., 2012; K. M. Sefc, unpublished data). Significantly different concentrations of the same types of integumentary carotenoids were found between red and blue Pundamilia spp. as well as between the red and yellow body regions of P. nyererei (Maan et al., 2008) and between the gold and gray color morphs of the Midas cichlid (Lin et al., 2010). These findings suggest that, as in birds, cichlid carotenoid pigmentation may be determined by different metabolic pathways in different species or populations.

Fig. 3.

Geographic color variation in a cichlid fish. Phylogenetic relationships among selected examples of the rich variety of differently colored populations of the genus Tropheus (Schupke, 2003; Konings, 2013) reveal differentiation in body and fin coloration between close relatives as well as repeated evolution of similar colors. The taxonomy of the genus is not fully resolved; nominal and suggested species supported by genetic data and assortative mating are indicated. The population tree is based on data from Egger et al. (2007) and Koblmüller et al. (2011). Photographs: Ad Konings (T. sp. Mpimbwe), Wolfgang Gessl and Peter Berger.

4.3. Genetic basis of carotenoid coloration in cichlids

Heritability of carotenoid-based coloration has been demonstrated in different vertebrate species, but to date its genetic basis is only poorly understood (Olsson et al., 2013; Roulin and Ducrest, 2013). Walsh et al. (2012) developed a list of 11 candidate genes with potential roles in the uptake, deposition and degradation of carotenoids in vertebrates (see also Eriksson et al., 2008). Transporter proteins and enzymes involved in the uptake and metabolism of dietary carotenoids are particularly likely to be under genetic, rather than environmental, control (Yonekura and Nagao, 2007; Hill and Johnson, 2012). Genetic factors play a principal role in the generation of discrete variation, such as color polymorphisms or differentiation between closely related cichlid taxa (Magalhaes and Seehausen, 2010; Takahashi et al., 2013; but see Korzan et al., 2008).

The number of genes thus far implicated in cichlid carotenoid coloration is small. Analyses of gene expression in carotenoid-containing integument implicated the chromatophore formation genes csf1ra and Edn3b as candidate color genes in cichlids (Salzburger et al., 2007; Diepeveen and Salzburger, 2011; see also Section 4.1.). A QTL region for yellow fin coloration identified in Lake Malawi cichlids included neither csf1ra nor Edn3b, but contained two other candidate carotenoid genes, namely StAR, which could play a role in carotenoid binding and deposition, and BCDO2, which cleaves carotenoids into colorless metabolites (O'Quin et al., 2013). In the Midas cichlid, inheritance studies have suggested that a single locus is responsible for triggering the transition from gray to gold morph, which involves both melanophore death and carotenoid accumulation (Barlow, 1983; Henning et al., 2010; Fig. 1). Recently, a transcriptomics approach (Henning et al., 2013) identified several differentially expressed genes involved in melanophore maintenance and cell death. In contrast, the genes involved in the upregulation of carotenoid assimilation, transportation and deposition during the color morph transition have yet to be identified.

The orange blotch phenotype of certain Lake Malawi cichlid species, in which females display dark melanophore blotches on a background of xanthophores, was associated with up-regulation of the cichlid Pax7 gene, a member of the Pax3/7 subfamily (Roberts et al., 2009). The orange coloration in orange-blotch females is alcohol-soluble and therefore likely to be carotenoid-based (R. Roberts, pers. comm.). In zebrafish, Pax3 and Pax7 influence xanthophore specification (Pax3) and pigmentation (Pax7) as well as melanophore number and size (Pax3) (Minchin and Hughes, 2008). Cichlid females carrying the up-regulated allele of Pax7 (OB females) develop fewer but larger melanophores than the brown barred females. OB females vary in background color from white to orange depending on species and population, indicating that the identified allele affects the melanophore pattern but not the orange coloration in these cichlids (Roberts et al., 2009). One possible route for cichlid Pax7 to influence the xanthophore background in orange-blotch cichlids is via developmental trade-offs between decreased melanophore numbers and increased xanthophore numbers (R. Roberts, pers. comm.).

In Midas cichlids and Lake Malawi cichlids with the orange-blotch phenotype, and likely in many other cichlid species, the extent of carotenoid-based coloration on the body is contingent on the distribution of melanophores. This interaction makes the processes controlling melanophore patterning relevant to understanding the processes underlying carotenoid coloration. Studies in zebrafish and medaka provided a wealth of information about the genetics of melanin coloration in these model organisms (Rawls et al., 2001; Kelsh, 2004; Kelsh et al., 2009; Braasch and Liedtke, 2011; Yamanaka and Kondo, 2014). Several candidate melanophore-pattern genes have been studied in cichlids and may be involved in cichlid coloration (Sugie et al., 2004; Diepeveen and Salzburger, 2011; Gunter et al., 2011; O'Quin et al., 2013; but see Watanabe et al., 2007).

5. Gaps in our understanding of carotenoid-based coloration in cichlids

Carotenoids are important in many aspects of cichlid biology. The elaboration of carotenoid-pigmented structures via sexual selection is well documented. Much remains to be discovered, however, in areas such as carotenoid biochemistry, physiology and genetics. Basic data on the types and functions of carotenoids in cichlids, and their interactions with other metabolites, will allow the testing of hypotheses regarding the evolutionary significance of carotenoid coloration. Below, we specify some areas for future research that we believe will contribute significantly to our understanding of the evolution of carotenoid pigmentation in cichlid fishes, and in fishes more broadly.

5.1. What are the proximate mechanisms that determine, generate and control carotenoid-based coloration in cichlids?

The identification of esterified carotenoids – which are present in the integument of many cichlids – via high-performance liquid chromatography is more complicated than for non-esterified carotenoids, such as in bird feathers. The identification of integumentary carotenoids in cichlids (e.g. Lin et al., 2010) will allow us to assess whether different hues are produced by different types or by different concentrations of carotenoids, and whether similar hues in unrelated taxa result from similar or from taxon-specific mixtures of integumentary carotenoids. Differences in coloration among closely related taxa (e.g. Fig. 3) will make for particularly powerful tools to examine the relationship between carotenoid composition and coloration against similar physiological and ecological backgrounds. Furthermore, such information might allow us to link differences in diet, so important among lacustrine cichlids, to differences in coloration. Combining biochemistry with genome and transcriptome analyses will advance our understanding of the genetics and physiology of carotenoid-based coloration in cichlids and its rapid evolution. Research efforts along these lines will benefit greatly from advances in cichlid genomics (Tilapia Genome Project and Cichlid Genome Consortium, USA). Armed with this knowledge, we can then ask questions about the diversity of metabolic pathways leading towards particular types of carotenoids, and at which phylogenetic levels this variation emerges. Research on other types of chromatophores and pigments, and on structural coloration, will be required to understand and appreciate the interactions that influence the extent and intensity of carotenoid coloration. For example, chromatophore patterns determine the amount of carotenoids to be deposited in the integument, and signal strength can be modified by contrasts between adjacent areas or by overlap of chromatophore layers.

5.2. How do carotenoids interact with non-carotenoid pigments and structural colors?

Poikilothermic vertebrates do not rely solely on dietary carotenoids to produce yellow and red coloration; they can also synthesize pterin pigments. Pterins have been detected in the integument of several fish species (Rempeters et al., 1981; Ziegler et al., 2000; Grether et al., 2001). The balance between carotenoid and pterin based pigmentation is intriguing, because pterins theoretically allow the animals to display color largely independent of their diet and health (but see Grether et al., 2004). Interestingly, pterins do not appear to be significant determinants of coloration in the few cichlid species examined so far (P. nyererei: Maan et al., 2006b; T. moorii: Mattersdorfer et al., 2012; A. nigrofasciata: Brown et al., 2013a), but information from additional taxa is sorely needed. There are also unanswered questions regarding the interactions between carotenoids and other pigments such as melanins and structural color components such as iridophores (Brown et al., 2013a; San-Jose et al., 2013; Yamanaka and Kondo, 2014), which can modulate tissue brightness, hue and contrast (Grether et al., 2004).

5.3. How do environmental conditions influence carotenoid coloration?

Carotenoid-based coloration of cichlids responds to a number of factors including diet, health status and social stimulation (Katsuyama and Matsuno, 1988; Hofmann and Fernald, 2001; Maan et al., 2006b; Dijkstra et al., 2007; Kop et al., 2010). For example, androgens may be involved in mediating the social stimulation of carotenoid displays, and their possible contributions to the diversity of cichlid behavior and coloration as well as their concomitant impacts on immunity and oxidative status (Kurtz et al., 2007; Peters, 2007; Alonso-Alvarez et al., 2008) certainly merit further attention. As another example, the effects of diet on integumentary carotenoids depend on the availability and functionality of metabolic pathways, and interactions among diet, genotype and physiological state will shed light on proximate and ultimate mechanisms associated with carotenoid coloration (Lin et al., 2010). Finally, the physical environment plays a prominent role in the expression of carotenoid-based coloration. Barlow (1983) noted that the frequency of gold morph Midas cichlids varied among Nicaraguan lakes, and was positively correlated with lake turbidity. The African Rift lakes provide numerous examples of differences in male cichlid nuptial coloration (some of it only putatively carotenoid-based) due to depth, water clarity and substrate type (Seehausen et al., 2008; Maan et al., 2010; Pauers, 2011).

5.4. What do carotenoid-based ornaments signal in cichlids?

The conspicuous carotenoid-based coloration of many cichlids is likely to convey information on the bearer's condition, status and motivation. The use of this information in female choice (Maan et al., 2004; Pauers et al., 2004) and male–male competition (Evans and Norris, 1996) has been documented, but is not always obvious (Hermann et al., in review). Although female coloration is common among cichlids, its role in intersexual and intrasexual selection, particularly in reverse sexually-dichromatic species requires further study (Beeching et al., 1998; Tobler, 2007; Baldauf et al., 2011). In addition to clarifying the contexts in which carotenoids signals are used, it is particularly important to understand what information carotenoid signals actually convey. Numerous studies in a wide range of species have revealed correlations between carotenoid coloration and individual physical condition, but no single mechanism has received unequivocal support (Olson and Owens, 1998; Pérez-Rodríguez, 2009; Hill, 2011; Svensson and Wong, 2011). In cichlids, carotenoid signals are employed against the background of very different life histories, including contrasts between territoriality and non-territoriality, between monogamous and polygynous mating systems and between brood care and the absence thereof. It will be illuminating to examine how carotenoid physiology is affected by these life-history differences, and how this in turn affects carotenoid signaling (Fairhurst et al., 2014). Considering the conflicting results between tests of the carotenoid trade-off hypothesis in Old and New World cichlid species, which were supported in the former group but not in the latter, future research should focus on differences in proximate mechanisms in carotenoid conversion and utilization that may have occurred in > 57 million years since these groups diverged (Friedman et al., 2013).

6. Why cichlids?

Many of these questions outlined above can be addressed in other organisms, but we believe cichlids are a particularly important group for this kind of research for several reasons. On the one hand, understanding carotenoid physiology and biochemistry is important for our understanding of cichlid evolution. On the other hand, the extraordinary diversity of cichlids will help advance our understanding of the roles of carotenoids in organismal biology.

First, the rich diversity of cichlid color patterns promises opportunities to uncover a variety of genetic, cellular and physiological processes involved in carotenoid coloration and color pattern differentiation (Kocher, 2004). Variation in the extent of sexual dichromatism among related species can inform us about the regulation of color pattern expression (Gunter et al., 2011), as can the status-dependent color changes in the haplochromine cichlid A. burtoni, a model species in social neuroscience (Hofmann and Fernald, 2001; Fernald, 2012). Some cichlid species are economically important and the collective interests of the aquaculture industry for improved productivity and flesh coloration can be brought to bear on the subject of evolutionary physiology. The continued development of cichlid genomics, including whole genome sequences, will provide the genetic tools to isolate genes involved in carotenoid absorption, transport and conversion. Testing the function of isolated genes has come within reach with the successful creation of transgenic cichlids (Fujimura and Kocher, 2011; Juntti et al., 2013). The relevance of these findings will certainly extend to other taxa in the conspicuously colorful order of Perciform fishes, and beyond to other species-rich vertebrate groups.

Second, the aforementioned variation in coloration can help us to better understand the relationship between phenotypic plasticity and speciation (Pfennig et al., 2010). Cichlid fishes are textbook cases of adaptive radiation and evolutionary diversification, and we know that color patterns and differences in diet are both important factors involved in speciation in cichlids. For example, assortative mating and social dominance based on carotenoid-based coloration contribute to speciation and species coexistence (Seehausen and van Alphen, 1998; Elmer et al., 2009; Dijkstra and Groothuis, 2011). Moreover, color pattern differences occur at different levels of phylogenetic divergence – polymorphic populations (Fig. 1), intraspecific geographic variation (Fig. 3) and variation across species and tribes – and are sometimes replicated in independent taxon pairs (Maan and Sefc, 2013). We predict that our understanding of this explosive adaptive radiation will be greatly improved if we succeed in expanding our knowledge of the proximate and ultimate mechanisms mediating carotenoid-based coloration, and combine it with the wealth of existing knowledge on cichlid ecology, behavior and phylogenetic relationships.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Berger, Wolfgang Gessl, Ad Konings and Adrienne Lightbourne for the images and drawings used in this paper. Comments on an earlier version of this manuscript were provided by Martine Maan. K.M.S. acknowledges financial support by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF P20883.B16). A.C.B. and E.D.C. thank Amherst College and the National Science Foundation (IOS-1051598; DDIG-1209744) for financial support.

References

- Alonso-Alvarez C., Pérez-Rodríguez L., Mateo R., Chastel O., Vinuela J. The oxidation handicap hypothesis and the carotenoid allocation trade-off. J. Evol. Biol. 2008;21:1789–1797. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C., Wong S.C., Fuller A., Ziglesky K., Earley R.L. 2014. Carotenoid-based coloration is associated with predation risk, competition, and breeding status in female convict cichlids (Amatitlania siquia) under field conditions. (in review) [Google Scholar]

- Backström T., Brännäs E., Nilsson J., Magnhagen C. Behaviour, physiology and carotenoid pigmentation in Arctic charr Salvelinus alpinus. J. Fish Biol. 2014;84:1–9. doi: 10.1111/jfb.12240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baerends G.P., Wanders J.B.W., Vodegel R. The relationship between marking patterns and motivational state in the pre-spawning behaviour of the cichlid fish Chromadotilapia guentheri (Sauvage) Neth. J. Zool. 1986;36:88–116. [Google Scholar]

- Baldauf S.A., Kullmann H., Bakker T.C.M., Thünken T. Female nuptial coloration and its adaptive significance in a mutual mate choice system. Behav. Ecol. 2011;22:478–485. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow G.W. Competition between color morphs of the polychromatic Midas cichlid Cichlasoma citrinellum. Science. 1973;179:806–807. doi: 10.1126/science.179.4075.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow G.W. The benefits of being gold: behavioral consequences of polychromatism in the Midas cichlid, Cichlasoma citrinellum. Environ. Biol. Fishes. 1983;8:235–247. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow G.W., McKaye K.R. A comparison of feeding, spacing, and aggression in color morphs of the Midas cichlid. II. After 24 hours without food. Behaviour. 1982:127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow G.W., Wallach S.J. Colour and levels of aggression in the Midas cichlid. Anim. Behav. 1976;24:814–817. [Google Scholar]

- Beeching S.C., Gross S.H., Bretz H.S., Hariatis E. Sexual dichromatism in convict cichlids: the ethological significance of female ventral coloration. Anim. Behav. 1998;56:1021–1026. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1998.0868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendich A., Olson J.A. Biological actions of carotenoids. FASEB J. 1989;3:1927–1932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount J.D., McGraw K.J. Carotenoids. Springer; 2008. Signal functions of carotenoid colouration; pp. 213–236. [Google Scholar]

- Blount J.D., Metclafe N.B., Birkhead T.R., Surai P.F. Carotenoid modulation of immune function and sexual attractiveness in zebra finches. Science. 2003;300:125–127. doi: 10.1126/science.1082142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonier F., Martin P.R., Moore I.T., Wingfield J.C. Do baseline glucocorticoids predict fitness? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009;24:634–642. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boughman J.W. How sensory drive can promote speciation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2002;17:571–577. [Google Scholar]

- Braasch I., Liedtke D. Encyclopedia of Fish Physiology: From Genome to Environment. Elsevier; 2011. Pigment genes and cancer genes; pp. 1971–1979. [Google Scholar]

- Braasch I., Schartl M., Volff J.-N. Evolution of pigment synthesis pathways by gene and genome duplication in fish. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007;7:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A.C. University of Massachusetts; Amherst: 2014. Honesty and carotenoids in a pigmented female fish (Ph.D. dissertation) [Google Scholar]

- Brown A.C., McGraw K.J., Clotfelter E.D. Dietary carotenoids increase yellow nonpigment coloration of female convict cichlids (Amantitlania nigrofasciata) Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2013;86:312–322. doi: 10.1086/670734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A.C., Leonard H.M., McGraw K.J., Clotfelter E.D. Maternal effects of carotenoid supplementation in an ornamented cichlid fish (Amantitlania siquia) Funct. Ecol. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Brush A.H. Pigments in hybrid, variant and melanic tanagers (birds) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1970;36:785–793. [Google Scholar]

- Brush A.H., Seifried H. Pigmentation and feather structure in genetic variants of the Gouldian finch, Poephila gouldiae. Auk. 1968;85:416–430. [Google Scholar]

- Candolin U. Changes in expression and honesty of sexual signalling over the reproductive lifetime of sticklebacks. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 2000;267:2425–2430. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clotfelter E.D., Ardia D.R., McGraw K.J. Red fish, blue fish: trade-offs between pigmentation and immunity in Betta splendens. Behav. Ecol. 2007;18:1139–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Costantini D., Møller A. Carotenoids are minor antioxidants for birds. Funct. Ecol. 2008;22:367–370. [Google Scholar]

- Costantini D., Fanfani A., Dell'Omo G. Effects of corticosteroids on oxidative damage and circulating carotenoids in captive adult kestrels (Falco tinnunculus) J. Comp. Physiol. B. 2008;178:829–835. doi: 10.1007/s00360-008-0270-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote J., Meylan S., Clobert J., Voituron Y. Carotenoid-based coloration, oxidative stress and corticosterone in common lizards. J. Exp. Biol. 2010;213:2116–2124. doi: 10.1242/jeb.040220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crozier G.F. Carotenoids of seven species of Sebastodes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1967;23:179–184. doi: 10.1016/0010-406x(67)90486-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickmann M.C., Schliwa M., Barlow G.W. Melanophore death and disappearance produces color metamorphosis in the polychromatic Midas cichlid (Cichlasoma citrinellum) Cell Tissue Res. 1988;253:9–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00221733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diepeveen E.T., Salzburger W. Molecular characterization of two endothelin pathways in East African cichlid fishes. J. Mol. Evol. 2011;73:355–368. doi: 10.1007/s00239-012-9483-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra P.D., Groothuis T.G.G. Male-male competition as a force in evolutionary diversification: evidence in haplochromine cichlid fish. Int. J. Evol. Biol. 2011;689254 doi: 10.4061/2011/689254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra P.D., Seehausen O., Groothuis T.G.G. Direct male–male competition can facilitate invasion of new colour types in Lake Victoria cichlids. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2005;58:136–143. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra P.D., Seehausen O., Gricar B.L.A., Maan M.E., Groothuis T.G.G. Can male–male competition stabilize speciation? A test in Lake Victoria haplochromine cichlid fish. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2006;59:704–713. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra P.D., Hekman R., Schulz R.W., Groothuis T.G.G. Social stimulation, nuptial colouration, androgens and immunocompetence in a sexual dimorphic cichlid fish. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2007;61:599–609. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra P.D., Hemelrijk C., Seehausen O., Groothuis T.G.G. Color polymorphism and intrasexual competition in assemblages of cichlid fish. Behav. Ecol. 2009;20:138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra P.D., Wiegertjes G.F., Forlenza M., van der Sluijs I., Hofmann H.A., Metcalfe N.B., Groothuis T.G.G. The role of physiology in the divergence of two incipient cichlid species. J. Evol. Biol. 2011;24:2639–2652. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger B., Koblmüller S., Sturmbauer C., Sefc K.M. Nuclear and mitochondrial data reveal different evolutionary processes in the Lake Tanganyika cichlid genus Tropheus. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007;7:137. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger B., Klaefiger Y., Theis A., Salzburger W. A sensory bias has triggered the evolution of egg-spots in cichlid fishes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmer K.R., Lehtonen T.K., Meyer A. Color assortative mating contributes to sympatric divergence of Neotropical cichlid fish. Evolution. 2009;63:2750–2757. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endler J.A. Natural selection on color patterns in Poecilia reticulata. Evolution. 1980;34:76–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1980.tb04790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson J., Larson G., Gunnarsson U., Bed'hom B., Tixier-Boichard M., Strömstedt L., Wright D., Jungerius A., Vereijken A., Randi E. Identification of the yellow skin gene reveals a hybrid origin of the domestic chicken. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M.R., Norris K. The importance of carotenoids in signaling during aggressive interactions between male firemouth cichlids (Cichlasoma meeki) Behav. Ecol. 1996;7:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Fairhurst G.D., Dawson R.D., Oort H., Bortolotti G.R. Synchronizing feather-based measures of corticosterone and carotenoid-dependent signals: what relationships do we expect? Oecologia. 2014;1–10 doi: 10.1007/s00442-013-2830-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernald R.D. Social control of the brain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012;35:133–151. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitze P.S., Cote J., San-Jose L.M., Meylan S., Isaksson C., Andersson S., Rossi J.-M., Clobert J. Carotenoid-based colours reflect the stress response in the common lizard. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox H.M., Vevers G. Macmillan; New York: 1960. The Nature of Animal Colors. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M., Keck B.P., Dornburg A., Eytan R.I., Martin C.H., Hulsey C.D., Wainwright P.C., Near T.J. Molecular and fossil evidence place the origin of cichlid fishes long after Gondwanan rifting. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 2013;280:20131733. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura K., Kocher T.D. Tol2-mediated transgenesis in tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Aquaculture. 2011;319:342–346. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2011.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin T.W. vol. 2. Chapman & Hall; New York: 1984. The biochemistry of the carotenoids. (Animals). [Google Scholar]

- Grether G.F., Hudon J., Endler J.A. Carotenoid scarcity, synthetic pteridine pigments and the evolution of sexual coloration in guppies (Poecilia reticulata) Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 2001;268:1245–1253. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grether G.F., Kolluru G.R., Nersissian K. Individual colour patches as multicomponent signals. Biol. Rev. 2004;79:583–610. doi: 10.1017/s1464793103006390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunter H.M., Clabaut C., Salzburger W., Meyer A. Identification and characterization of gene expression involved in the coloration of cichlid fish using microarray and qRT-PCR approaches. J. Mol. Evol. 2011;72:127–137. doi: 10.1007/s00239-011-9431-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Güroy B., Sahin I., Mantoglu S., Kayali S. Spirulina as a natural carotenoid source on growth, pigmentation and reproductive performance of yellow tail cichlid Pseudotropheus acei. Aquacult. Int. 2012;20:869–878. [Google Scholar]

- Harpaz S., Padowicz D. Color enhancement in the ornamental dwarf cichlid Microgeophagus ramirezi by addition of plant carotenoids to the fish diet. Isr. J. Aquacult. 2007;59:195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley R.C., Kennedy M.W. Are carotenoids a red herring in sexual display? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2004;19:353–354. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning F., Renz A.J., Fukamachi S., Meyer A. Genetic, comparative genomic, and expression analyses of the Mc1r locus in the polychromatic Midas cichlid fish (Teleostei, Cichlidae Amphilophus sp.) species group. J. Mol. Evol. 2010;70:405–412. doi: 10.1007/s00239-010-9340-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning F., Jones J.C., Franchini P., Meyer A. Transcriptomics of morphological color change in polychromatic Midas cichlids. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:171. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill G.E. Proximate basis of variation in carotenoid pigmentation in male house finches. Auk. 1992;109:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hill G.E. Condition-dependent traits as signals of the functionality of vital cellular processes. Ecol. Lett. 2011;14:625–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill G.E., Johnson J.D. The vitamin A-redox hypothesis: a biochemical basis for honest signaling via carotenoid pigmentation. Am. Nat. 2012;180:E127–E150. doi: 10.1086/667861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill G.E., Inouye C.Y., Montgomerie R. Dietary carotenoids predict plumage coloration in wild house finches. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 2002;269:1119–1124. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann H.A., Fernald R.D. What cichlids tell us about the social regulation of brain and behavior. J. Aquacult. Aquat. Sci. 2001;9:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hudon J. Showiness, carotenoids, and captivity: a comment on Hill (1992) Auk. 1994;111:218–221. [Google Scholar]

- Hudon J., Capparella A.P., Brush A.H. Plumage pigment differences in manakins of the Pipra erythrocephala superspecies. Auk. 1989;106:34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hudon J., Hudon G.F., Millie D.F. Marginal differentiation between the sexual and general carotenoid pigmentation of guppies (Poecilia reticulata) and a possible visual explanation. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2003;76:776–790. doi: 10.1086/378138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye C.Y., Hill G.E., Stradi R.D., Montgomerie R. Carotenoid pigments in male house finch plumage in relation to age, subspecies, and ornamental coloration. Auk. 2001;118:900–915. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J.D., Hill G.E. Is carotenoid ornamentation linked to the inner mitochondria membrane potential? A hypothesis for the maintenance of signal honesty. Biochimie. 2013;95:436–444. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juntti S.A., Hu C.K., Fernald R.D. Tol2-mediated generation of a transgenic haplochromine cichlid, Astatotilapia burtoni. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuyama M., Matsuno T. Carotenoid and vitamin A, and metabolism of carotenoids, beta-carotene, canthaxanthin, astaxanthin, zeaxanthin, lutein and tunaxanthin in tilapia Tilapia nilotica. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B. 1988;90:131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Katsuyama M., Komori T., Matsuno T. Metabolism of three stereoisomers of astaxanthin in the fish, rainbow trout and tilapia. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B. 1987;86:1–5. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(87)90165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsh R.N. Genetics and evolution of pigment patterns in fish. Pigment Cell Res. 2004;17:326–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2004.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsh R.N., Harris M.L., Colanesi S., Erickson C.A. Stripes and belly-spots—a review of pigment cell morphogenesis in vertebrates. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2009;20:90–104. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblmüller S., Salzburger W., Obermüller B., Eigner E., Sturmbauer C., Sefc K.M. Separated by sand, fused by dropping water: habitat barriers and fluctuating water levels steer the evolution of rock-dwelling cichlid populations in Lake Tanganyika. Mol. Ecol. 2011;20:2272–2290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocher T.D. Adaptive evolution and explosive speciation: the cichlid fish model. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:288–298. doi: 10.1038/nrg1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodric-Brown A. Sexual dichromatism and temporary color changes in the reproduction of fishes. Am. Zool. 1998;38:70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Konings A. Cichlid Press; El Paso, Texas: 2013. Tropheus in their natural habitat. [Google Scholar]

- Kop A., Durmaz Y. The effect of synthetic and natural pigments on the colour of the cichlids (Cichlasoma severum sp., Heckel 1840) Aquacult. Int. 2008;16:117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Kop A., Durmaz Y., Hekimoglu M. Effect of natural pigment sources on colouration of cichlid. J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2010;9:566–569. [Google Scholar]

- Korzan W.J., Fernald R.D. Territorial male color predicts agonistic behavior of conspecifics in a color polymorphic species. Behav. Ecol. 2007;18:318–323. [Google Scholar]

- Korzan W.J., Robison R.R., Zhao S., Fernald R.D. Color change as a potential behavioral strategy. Horm. Behav. 2008;54:463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz J., Kalbe M., Langefors Ã., Mayer I., Milinski M., Hasselquist D. An experimental test of the immunocompetence handicap hypothesis in a teleost fish: 11-ketotestosterone suppresses innate immunity in three-spined sticklebacks. Am. Nat. 2007;170:509–519. doi: 10.1086/521316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendvai A.Z., Giraudeau M., Németh J., Bakó V., McGraw K. Carotenoid-based plumage coloration reflects feather corticosterone levels in male house finches (Haemorhous mexicanus) Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2013;67:1817–1824. [Google Scholar]

- Lin S.M., Nieves-Puigdoller K., Brown A.C., McGraw K.J., Clotfelter E.D. Testing the carotenoid trade-off hypothesis in the polychromatic Midas cichlid, Amphilophus citrinellus. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2010;83:333–342. doi: 10.1086/649965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiseau C., Fellous S., Haussy C., Chastel O., Sorci G. Condition-dependent effects of corticosterone on a carotenoid-based begging signal in house sparrows. Horm. Behav. 2008;53:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano G.A. Carotenoids, parasites, and sexual selection. Oikos. 1994;70:309–311. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano G.A. Carotenoids, immunity, and sexual selection: comparing apples and oranges? Am. Nat. 2001;158:200–203. doi: 10.1086/321313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maan M.E., Sefc K.M. Colour variation in cichlid fish: developmental mechanisms, selective pressures and evolutionary consequences. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2013;xx doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maan M.E., Seehausen O., Söderberg L., Johnson L., Ripmeester E.A.P., Mrosso H.D.J., Taylor M.I., van Dooren T.J.M., van Alphen J.J.M. Intraspecific sexual selection on a speciation trait, male coloration, in the Lake Victoria cichlid Pundamilia nyererei. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 2004;271:2445–2452. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maan M.E., Hofker K.D., van Alphen J.J.M., Seehausen O. Sensory drive in cichlid speciation. Am. Nat. 2006;167:947–954. doi: 10.1086/503532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maan M.E., van der Spoel M.P.Q.J., van Alphen J.J.M., Seehausen O. Fitness correlates of male coloration in a Lake Victoria cichlid fish. Behav. Ecol. 2006;17:691–699. [Google Scholar]

- Maan M.E., van Rooijen A.M.C., van Alphen J.J.M., Seehausen O. Parasite-mediated sexual selection and species divergence in Lake Victoria cichlid fish. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2008;94:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Maan M.E., Seehausen O., van Alphen J.J.M. Female mating preferences and male coloration covary with water transparency in a Lake Victoria cichlid fish. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2010;99:398–406. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhaes I.S., Seehausen O. Genetics of male nuptial colour divergence between sympatric sister species of a Lake Victoria cichlid fish. J. Evol. Biol. 2010;23:914–924. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.01960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattersdorfer K., Koblmüller S., Sefc K.M. AFLP genome scans suggest divergent selection on colour patterning in allopatric colour morphs of a cichlid fish. Mol. Ecol. 2012;21:3531–3544. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw K.J., Ardia D.R. Carotenoids, immunocompetence, and the information content of sexual colors: an experimental test. Am. Nat. 2003;162:704–712. doi: 10.1086/378904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw K.J., Lee K., Lewin A. The effect of capture-and-handling stress on carotenoid-based beak coloration in zebra finches. J. Comp. Physiol. A. 2011;197:683–691. doi: 10.1007/s00359-011-0631-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe N.B., Alonso-Alvarez C. Oxidative stress as a life-history constraint: the role of reactive oxygen species in shaping phenotypes from conception to death. Funct. Ecol. 2010;24:984–996. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A. Phylogenetic relationships and evolutionary processes in East African cichlid fishes. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1993;8:3–8. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(93)90255-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minchin J.E.N., Hughes S.M. Sequential actions of Pax3 and Pax7 drive xanthophore development in zebrafish neural crest. Dev. Biol. 2008;317:508–522. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelissen M. Contribution to the ethology of Tropheus moorii Boulenger (Pisces, Cichlidae) and a discussion of the significance of its colour pattern. Rev. Zool. Afr. 1976;90:17–29. [Google Scholar]

- O’Quin C.T., Drilea A.C., Conte M.A., Kocher T.D. Mapping of pigmentation QTL on an anchored genome assembly of the cichlid fish, Metraclima zebra. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:287. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson V.A., Owens I.P.F. Costly sexual signals: are carotenoids rare, risky, or required? Trends Ecol. Evol. 1998;13:510–514. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01484-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson M., Stuart-Fox D., Ballen C. Genetics and evolution of colour patterns in reptiles. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2013;xx doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan C.-H., Chien Y.-H. Effects of dietary supplementation of alga Haematococcus pluvialis (Flotow), synthetic astaxanthin and beta-carotene on survival, growth, and pigment distribution of red devil, Cichlasoma citrinellum (Günther) Aquacult. Res. 2009;40:871–879. [Google Scholar]

- Parichy D.M. Evolution of danio pigment pattern development. Heredity. 2006;97:200–210. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parichy D.M., Ransom D.G., Paw B., Zon L.I., Johnson S.L. An orthologue of the kit-related gene fms is required for development of neural crest-derived xanthophores and a subpopulation of adult melanocytes in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Development. 2000;127:3031–3044. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.14.3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauers M.J. One fish, two fish, red fish, blue fish: Geography, ecology, sympatry, and male coloration in the Lake Malawi cichlid genus Labeotropheus (Perciformes: Cichlidae) Int. J. Evol. Biol. 2011;575469 doi: 10.4061/2011/575469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauers M.J., McKinnon J.S., Ehlinger T.J. Directional sexual selection on chroma and within-pattern colour contrast in Labeotropheus fuelleborni. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 2004;271:S444–S447. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2004.0215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez C., Lores M., Velando A. Availability of nonpigmentary antioxidant affects red coloration in gulls. Behav. Ecol. 2008;19:967–973. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Rodríguez L. Carotenoids in evolutionary ecology: re-evaluating the antioxidant role. Bioessays. 2009;31:1116–1126. doi: 10.1002/bies.200900070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Rodriguez L., Mougeot F., Alonso-Alvarez C. Carotenoid-based coloration predicts resistance to oxidative damage during immune challenge. J. Exp. Biol. 2010;213:1685–1690. doi: 10.1242/jeb.039982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A. Testosterone and carotenoids: an integrated view of trade-offs between immunity and sexual signalling. Bioessays. 2007;29:427–430. doi: 10.1002/bies.20563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfennig D.W., Wund M.A., Snell-Rood E.C., Cruickshank T., Schlichting C.D., Moczek A.P. Phenotypic plasticity's impacts on diversification and speciation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010;25:459–467. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryke S.R. Is red an innate or learned signal of aggression and intimidation? Anim. Behav. 2009;78:393–398. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls J.F., Mellgren E.M., Johnson S.L. How the zebrafish gets its stripes. Dev. Biol. 2001;240:301–314. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reboul E., Borel P. Proteins involved in uptake, intracellular transport and basolateral secretion of fat-soluble vitamins and carotenoids by mammalian enterocytes. Prog. Lipid Res. 2011;50:388–402. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rempeters G., Henze M., Anders F. Carotenoids and pteridines in the skin of interspecific hybrids of Xiphophorus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B. 1981;69:91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R.B., Ser J.R., Kocher T.D. Sexual conflict resolved by invasion of a novel sex determiner in Lake Malawi cichlid fishes. Science. 2009;326:998–1001. doi: 10.1126/science.1174705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roulin A., Ducrest A.-L. Genetics of coloration in birds. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2013;xx doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzburger W., Mack T., Verheyen E., Meyer A. Out of Tanganyika: genesis, explosive speciation, key-innovations and phylogeography of the haplochromine cichlid fishes. BMC Evol. Biol. 2005;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzburger W., Braasch I., Meyer A. Adaptive sequence evolution in a color gene involved in the formation of the characteristic egg-dummies of male haplochromine cichlid fishes. BMC Biol. 2007;5:51. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-5-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San-Jose L.M., Granado-Lorencio F., Fitze P.S. Dietary lipids reduce the expression of carotenoid-based coloration in Lacerta vivipara. Func. Ecol. 2012;26:646–656. [Google Scholar]

- San-Jose L.M., Granado-Lorencio F., Sinervo B., Fitze P.S. Iridophores and not carotenoids account for chromatic variation of carotenoid-based coloration in common lizards (Lacerta vivipara) Am. Nat. 2013;181:396–409. doi: 10.1086/669159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupke P. Aqualog, ACS GmbH, Rodgau; Germany: 2003. African cichlids II. Tanganyika I. Tropheus. [Google Scholar]

- Seehausen O., van Alphen J.J.M. The effect of male coloration on female mate choice in closely related Lake Victoria cichlids (Haplochromis nyererei complex) Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1998;42:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Seehausen O., Terai Y., Magalhaes I.S., Carleton K.L., Mrosso H.D.J., Miyagi R., van der Sluijs I., Schneider M.V., Maan M.E., Tachida H., Imai H., Okada N. Speciation through sensory drive in cichlid fish. Nature. 2008;455:620–627. doi: 10.1038/nature07285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sefc K.M., Hermann C.M., Steinwender B., Brindl H., Zimmermann H., Mattersdorfer K., Postl L., Makasa L., Sturmbauer C., Koblmüller S. 2014. Asymmetries in reproductive isolation and dominance relationships between allopatric cichlid color morphs. (in review) [Google Scholar]

- Sugie A., Terai Y., Ota R., Okada N. The evolution of genes for pigmentation in African cichlid fishes. Gene. 2004;343:337–346. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson P., Wong B. Carotenoid-based signals in behavioural ecology: a review. Behaviour. 2011;148:131–189. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T., Sota T., Hori M. Genetic basis of male colour dimorphism in a Lake Tanganyika cichlid fish. Mol. Ecol. 2013;22:3049–3060. doi: 10.1111/mec.12120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theis A., Salzburger W., Egger B. The function of anal fin egg-spots in the cichlid fish Astatotilapia burtoni. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler M. Reversed sexual dimorphism and female courtship in the Topaz cichlid, Archocentrus myrnae (Cichlidae, Teleostei), from Costa Rica. Southwest. Nat. 2007;52:371–377. [Google Scholar]

- Toomey M.B., Butler M.W., McGraw K.J. Immune-system activation depletes retinal carotenoids in house finches (Carpodacus mexicanus) J. Exp. Biol. 2010;213:1709–1716. doi: 10.1242/jeb.041004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinkler M., Albrecht T. Carotenoid maintenance handicap and the physiology of carotenoid-based signalisation of health. Naturwissenschaften. 2010;97:19–28. doi: 10.1007/s00114-009-0595-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Lintig J. Colors with functions: elucidating the biochemical and molecular basis of carotenoid metabolism. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2010;30:35–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-080508-141027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Schantz T., Bensch S., Grahn M., Hasselquist D., Wittzell H. Good genes, oxidative stress and condition-dependent sexual signals. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 1999;266:1–12. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh N., Dale J., McGraw K.J., Pointer M.A., Mundy N.I. Candidate genes for carotenoid coloration in vertebrates and their expression profiles in the carotenoid-containing plumage and bill of a wild bird. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 2012;279:58–66. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.0765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M., Hiraide K., Okada N. Functional diversification of kir7.1 in cichlids accelerated by gene duplication. Gene. 2007;399:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber R., Barlow G., Brush A.H. Pigments of a color polymorphism in a cichlid fish. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B. 1973;44:1127–1135. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(73)90265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedekind C., Meyer P., Frischknecht M., Niggli U.A., Pfander H. Different carotenoids and potential information content of red coloration of male three-spined stickleback. J. Chem. Ecol. 1998;24:787–801. [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka H., Kondo S. In vitro analysis suggests that difference in cell movement during direct interaction can generate various pigment patterns in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315416111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz S., Ergun S., Soytas N. Enhancement of growth performance and pigmentation in red Oreochromis mossambicus associated with dietary intake of astaxanthin, paprika, or capsicum. Isr. J. Aquacult. 2013;xx [Google Scholar]

- Yonekura L., Nagao A. Intestinal absorption of dietary carotenoids. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007;51:107–115. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200600145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler I., McDonald T., Hesslinger C., Pelletier I., Boyle P. Development of the pteridine pathway in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:18926–18932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910307199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]