Abstract

Background:

Chronic non-cancer pain (CP) is one of the most common complaints that bring patients to the hospital. When pain persists, people move from doctor-to-doctor seeking for help, thus the burden of CP is huge. This study, therefore was aimed at assessing attitude and knowledge of doctors in three teaching hospitals in Nigeria to CP.

Materials and Methods:

Structured questionnaire was administered to doctors practicing at the University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, Usmanu Danfodio University Teaching Hospital and University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital. Responses were graded on maximum scale of five.

Results:

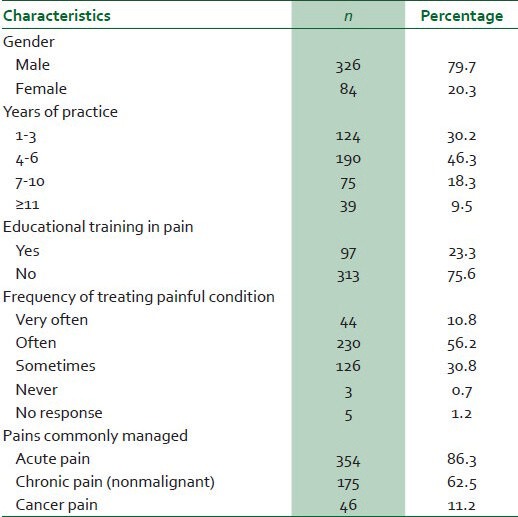

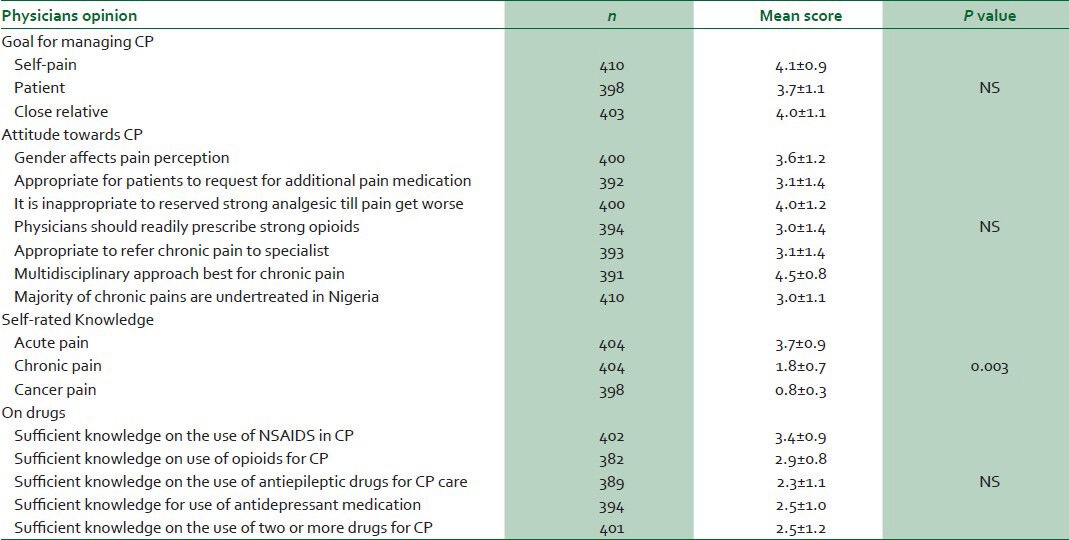

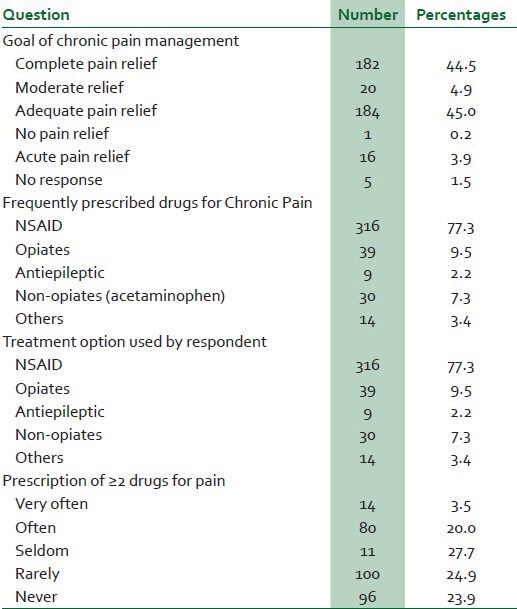

Of the 410 doctors who participated in study, 79.7% were men. Their years of practice varied from 1 year to 20 years (mean SD = 4.5 ± 1.7 years). Close to 58% of participants were resident doctors, 36.4% medical officers and 8.6% consultants. Only 23.3% of participants had basic medical or postgraduate training on pain management. The physicians’ mean goal of treating CP in patients was 3.7 ± 1.1, compared to 4.0 ± 1.1 in close relative and 4.1 ± 0.9 for doctors’-self pain. Only 9.5% of doctors use opioids for CP compared to 73% who use Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Few doctors (23%) use ≥2 drugs to treat CP. Doctors were indifferent on the appropriateness of patients with CP to request for additional analgesics (mean score = 3.1 + 1.4). Doctors’ self-rated knowledge of CP was 1.8 ± 0.7 compared to 4.1 ± 0.9 for acute and 0.8 ± 0.3 for cancer pains (P = 0. 003).

Conclusion:

Incorporation of pain management into continuing medical education could help improve observed deficiency in doctors’ knowledge of pain treatment which resulted from lack of basic medical education on pain.

Keywords: Attitude, chronic pain, doctors, knowledge, treatment

INTRODUCTION

Chronic pains by definition are those pains which persist beyond the initial insult that triggered them and the expected time for healing, which is assumed to be 3 months, with no ongoing tissue damage identified.1 Chronic pain (CP) is one of the most common complaints for which patients visit the hospital.2 The persistence of pain results in people moving from doctor-to-doctor to seek for help. This health seeking behaviour makes patients with CP use healthcare facilities more frequently than the rest of the population.3 This condition is a common cause of loss of working hour and early retirements among individual less than 45 years.1,2,4 The burden of persistent pain is substantial for the individual and society with community prevalence that varies from 11.5% to 55.2%.5,6 Chronic pain is responsible for alterations in patient's physical, emotional and social functions and is associated with poor quality of life.7 The continuing rise in number of non-orthodox cure for CP in the community despite availability of several analgesics attest to the enormity and importance of this condition.8,9

Reported barriers to optimize treatment of CP have been divided into three broad categories: Provider-related barrier,10,11 system-related barriers12 and patients-related barriers.13,14 Of these three, provider-related limitations have been found to be easy to assess, measure and corrected. Insufficient knowledge and education of physicians in CP management is a recurring factor from several studies.1,2 The continuance of this hindrance means many people will continue to live with unnecessary pain.

The aim of this study, therefore, was to assess the attitude, knowledge and practice of doctors in three teaching hospitals from three geopolitical zones of Nigeria (middle belt, Northeast and Northwest) in managing their patients with CP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Survey instrument used in this study was a self-administered standard questionnaire adapted from previously published works.1,15 The study was carried out at the University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital (middle belt), Usmanu Danfodio University Teaching Hospital (North west) and University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital (North east). One hundred questionnaires were sent to doctors in each of the three cadres of physicians (medical officers, resident doctors and consultants) practicing in each of the three study centres. The study was carried out between June and December 2009. Responses to knowledge and attitudinal questions were graded on a maximum scale of five (strongly agree-5, agree-4, neutral-3, disagree-2, strongly disagree-1). The maximum score on experience/practice-based questions was five (extremely confident-5, very confident-4, confident-3, not too confident-2, not confident-1).

DATA ANALYSIS

Collected data were analysed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 15 (SPSS Inc). Frequency distributions of some variables were determined. Mean scores of responses and standard deviations were determined for responses. Independent and dependent variables were cross tabulated to examine the association. Chi-square was used to test for level of statistical significance. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of the 600 questionnaires distributed, 410 were returned filled given a response rate of 68.3%. Respondents were 79.7% men and 20.3% women. The respondents years of clinical practice varied from 1 year to 20 years with a mean (SD) of 4.5 ± 1.7years. Close to 58% of participants were resident doctors, 36.4% - medical officers and 8.64% — consultants. Only 23.3% of the participants had had formal training on pain. The majority (67%) of physicians indicated that they were involved in treating patients with pain in their practice. Acute pain was the most frequently treated by 86.6% of doctors. Close to 62.3% of doctors indicated that they treat chronic benign pain and 11.2% cancer pain. Table 1 show background characteristic of study participants. Doctors were asked to rate their knowledge of treating various kinds of pains. They indicated they were more knowledgeable in managing acute pain compared to chronic and cancer pains. There was a significant difference in mean scores of doctor's self-rated knowledge of the three types of pain with P = 0.003. Regarding various treatment options for CP, physicians were more knowledgeable of Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) with a mean score of 3.4 ± 0.9 compared to mean score of 2.9 ± 0.8 for their self-rated knowledge of opioids usage for CP. Physicians were least knowledgeable on the use of transcutaneous electrical nervous stimulation (TENs) with a mean score of 1.9 ± 1.1. The difference in mean value of responses was statically significant (P = 0.02). The mean score of physicians’ responses showed their knowledge on the use of two or more drugs for chronic pain was poor. Doctors’ self-rated responses to knowledge-based questions on treatment options for CP is shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Background characteristics of doctors

Table 2.

Physicians’ attitude and self-rated knowledge

Participating physicians were requested to indicate their goal for treating CP in patients, a close relative and for themselves. The mean score of doctors’ responses for their goal in treating CP in patients was lowest (3.7 ± 1.1) compared to mean score of 4.1 ± 0.9 for treating their own CP and 4.0 ± 1.1 in close relative but the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The majority of doctors’ had a right view that it is inappropriate to withhold adequate analgesia from a patient with CP until pain get worse with a mean score of 4.0 ± 1.2. However, they were neutral in their responses as to whether gender influence CP behaviours with a mean score of 3.6 ± 1.2. Doctors were also neutral in their responses to question if it was appropriate for patients with CP to request for additional analgesics to their current medication with mean responses of 3.1 ± 1.4. Participants were unclear with a mean score of 3.0 ± 1.4 for questions about the need to give strong opiate to patients with CP. Physicians’ responses likewise revealed neutrality on the need to refer patients with CP to pain specialist (3.1 ± 1.4). On the contrary, majority of doctors favour a multidisciplinary approach for treating CP with a mean score of 4.5 ± 0.8. Finally, the participants were asked their views on whether CP was under treated in Nigeria. Doctors’ responses revealed that they were unclear with a mean score of 3.0 ± 1.1. Table 2 showed Physicians’ opinion to attitudinal and knowledge-based questions.

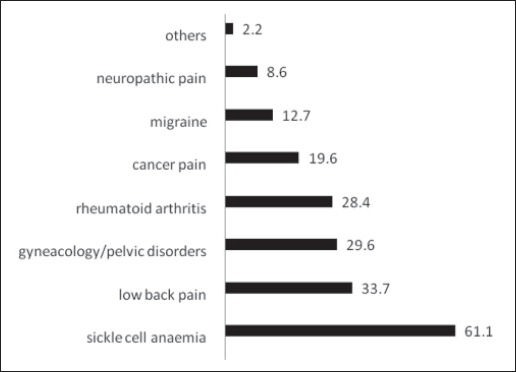

Physicians’ responses showed they are often involved in caring for patients with painful conditions. Acute pains were most frequently managed by 86.3% of physicians, 62.5% managed chronic non-cancer pain and 11.2% cancer pain. The three commonest causes of chronic pain indicated by doctors were sickle cell anemia (61.1%), low back pain (33.7%) and pelvic disorders (29.6%). Others forms of CP seen from the doctors’ responses are shown in Figure 1. The most commonly prescribed analgesic medication by this cross of clinicians was NSAIDs as it was indicated by 73% respondents, while only 9.5% doctors indicated to use opiate frequently. Close to 23% of physicians do give two or more drugs to patients with CP. This is further highlighted in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Causes of chronic pain

Table 3.

Practice of pain relief

DISCUSSION

Management of pain, whether acute or chronic pain, is a common problem in most clinical practices in low-and-middle income countries.2,7,10,11,12 Findings from this study showed that doctors were comfortable treating acute but not chronic pain. They seem to have good goal towards achieving adequate pain relief. However, doctors in this study demonstrated some deficiencies in knowledge regarding CP management which is likely to hinder their goal of adequate pain relief. This was evident by their low mean score on knowledge-based questions regarding pain management and neutrality towards attitudinal questions. This corroborates earlier report that inadequate knowledge about pain management is an important barrier to optimum pain management in developing countries.10,16,17 In most developing countries, pain management takes low priority due to limited and poor allocation of resources while healthcare is centered mainly on public health issues with main focus towards eradication of communicable disease such as malaria, Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), tuberculosis, and childhood immunisation.2,11,12 In these countries, there exists a lack of medical education on pain in most medical school curricula.12,18,19 In this report, only 23.3% of doctors had formal training on pain either during undergraduate or postgraduate medical education which support above mentioned studies. It can, therefore, be assumed that patients under the care of such doctors are likely to receive suboptimal treatment for pain. A recent publication of the International Association for Study of Pain (IASP) supports finding of this study.20 In the publication, IASP surmised that inadequate pain education in medical schools and during specialty trainings was an important factor responsible for abysmal knowledge of doctors regarding pain in clinical practice.18,20 Because several clinicians will at one point in their practice be confronted with pain management, a medical degree without core knowledge in pain management should be considered inadequate.20

Established goal for treating CP is to provide as much pain relief as possible and to improve functioning where it is impossible to eliminate pain. Doctors in this study seem to have good goal for CP management but they had a bias towards better self-pain management than for patients. This trend can only be changed through better education on ethics of pain management. Physicians expressed confidence regarding their knowledge of NSAIDs and acetaminophen for treating CPs better than the use of opioids. On the treatment ladder of pain management, NSAIDs and paracetamol have been recommended as first-line agents for treating mild-to-moderate pain especially acute pain.1 But prolonged use of NSAIDs in CP warrant caution and need to be discouraged since it may be associated with potentially fatal peptic ulceration and bleeding.1,2,7 Next on the ladder of pain management are opioids,1 but unfortunately the majority of doctors are not familiar with used of opioids for CP in this study. This is evident by the response that only 9.5% of doctors have used opioids for treating CP. This finding agrees with earlier reports where it has been shown that doctors are not familial with opiate usage for pain and are unwilling to use this medication in patients with persisting non-cancer persistent pains even when there appear to be no suitable alternatives.12,15 Clinical and laboratory data have shown that opioids are effective pain killers against most kinds of pain15 although there might be a need to exercise caution in its use. Reasons why physicians remain unwilling to give opiates for pain include fear of abuse and addiction, side effects such as constipation and respiratory depression, drowsiness, cost and relative unavailability in most hospitals in developing countries.1,12,20 Other alternative medication useful for treating CP include anticonvulsant drugs,21 which were originally intended to treat epileptic seizures. The mechanism of blocking sodium channels by antiseizure drugs like carbamazepine, topiramate and lamotrignene, with resultant reduction in neuronal transmission makes them effective for CP.22 Doctors in this study appear not to be very familiar with the use of anticonvulsant for CP.

It was not surprising that sickle cell disease was the commonest cause of CP mention by clinicians in this study. Nigeria has been reported to have the highest incidence of sickle cell disease worldwide and chronic pain is the hallmark of severity of the disease.23 The second most common cause of CP reported by doctors was low back pain. This has been earlier reported to be common amongst Nigeria with prevalence of 17-61%.4,24

The IASP protocol for CP management recommended a multidisciplinary approach to care, which involves use of other forms of therapy like stress relief and relaxation, physical therapy, improved sleep and nutritional habits along with analgesics.2 Only one-quarter of physicians in this study use more than one analgesics to treat CP. Although physicians were neutral to several attitudinal questions on how to treat CP, most of their responses showed they favour multidisciplinary approaches to CP management. This indicates that doctors will definitely benefit from more information on better ways of caring for chronic pains.

CONCLUSION

The finding from this survey showed that most doctors are involved in treating patients with chronic pain in their clinical practice. Doctors seem to have good goal toward pain management but their gap in knowledge of pain due to lack of pain education during basic medical and postgraduate training limit their effectiveness in treating chronic pain. Inadequate pain management often causes huge socioeconomic loss both to the affected and the community and is associated with reduced quality of life.25,26 It might be necessary to include pain management into doctor's continue medical education program which has been made mandatory in Nigeria. This will help to fill up the observed lacunae in knowledge of pain management and will indirectly impact positively on doctors’ attitudes towards chronic pain management.

Limitation of this study includes the self-assessment nature and restricted choice of responses. These could have introduced some biases to responses which might not necessarily be a true reflection of the physician's practice. Likewise this study was on doctors’ perspective of managing CP without patients input. It may be necessary to look at patient's perspective in the near future as this could help determine the full extent of the observed inadequacy. Albeit, finding of this study has shown that doctors’ knowledge and attitude towards CP management is suboptimal and this is relevant to clinical practice in the country.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Classification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Prepared by the International Association for the Study of Pain, Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain Suppl. 1986;3:S1–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashburn MA, Staats PS. Management of chronic pain. Lancet. 1999;353:1865–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04088-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elliot AM, Smith BH, Penny KI, Smith WC, Chambers WA. The epidemiology of chronic pain in community. Lancet. 1999;354:1248–52. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)03057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenberg D, Davis R, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, van Rompay M, et al. Trends in alternative medicine in the United States, 1990-1997: Results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Omokhodion FO, Sanya AO. Risk factors for lowback pain among office worker in Ibadan, Southwest Nigeria. Occup Med (Lond) 2003;53:287–9. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqg063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schopflocher D, Taenzer P, Jovey R. The prevalence of chronic pain in Canada. Pain Res Manag. 2011;16:445–50. doi: 10.1155/2011/876306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonica JJ. Definition and taxonomy of pain. In: Bonica JJ, editor. The Management of Pain. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldenberg DL. Fibromyalgia syndrome. An emerging but controversial condition. JAMA. 1987;257:2782–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.257.20.2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunnarsdottir S, Donovan HS, Ward S. Interventions to overcome clinician – and patient -related barriers to pain management. Nurs Clin North Am. 2003;38:419–34. doi: 10.1016/s0029-6465(02)00093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fields HL. The doctor's dilemma: Opiates analgesics and chronic pain. Neuron. 2011;69:591–4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fazeny B, Muhm M, Hauser I, Wenzel C, Mares P, Berzlanovich A, et al. Barrier in cancer pain management. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2000;112:978–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilson AM, Joranson DE, Maurer MA. Improving state pain policies: Recent progress and continuing opportunities. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:341–53. doi: 10.3322/CA.57.6.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward SE, Goldberg N, Miller-McCauley V, Mueller C, Nolan A, Pawlik-Plank D, et al. Patient-related barriers to management of cancer pain. Pain. 1993;52:319–24. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90165-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin CC. Barriers to the analgesic management of cancer pain: A comparison of attitudes of Taiwanese patients and their family caregivers. Pain. 2000;88:7–14. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00303-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobsen R, Sjogren P, Moldrup C, Christrup L. Patient-related barrier to cancer pain management with opioid analgesics: A systematic review. J Opioid Manag. 2007;3:207–14. doi: 10.5055/jom.2007.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macpherson C, Aarons D. Overcoming barriers to pain relief in the Caribbean. Dev World Bioeth. 2009;9:99–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2009.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim R. Improving cancer pain management in Malaysia. Oncology. 2008;74(suppl 1):24–34. doi: 10.1159/000143215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schofield P. Pain education and current curricula for older adults. Pain Med. 2012;13(Suppl 2):S51–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green CR, Wheeler JR, Laporte F, Marchant B, Guerrero E. How well is chronic pain managed? Who does it well? Pain Med. 2002;3:56–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2002.02003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loeser JD. IASP clinical Pain Update. 2012;XX:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen TS. Anticonvulsants in neuropathic pain: Rationale and clinical evidence. Eur J Pain. 2002;6(Suppl A):61–8. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2001.0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Tulder MW. Low back pain and sciatica. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:2501–13. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200010010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor LE, Stotts NA, Humphreys J, Treadwell MJ, Miaskowski C. A review of the literature on the multiple dimensions of chronic pain in adults with sickle cell disease. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:416–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Birabi BN, Dienye PO, Ndukwu GU. Prevalence of low back pain among peasant farmers in a rural community in South South Nigeria. Rural Remote Health. 2012;12:1920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snook SH. The cost of back pain in industry. Occup Med. 1988;3:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Botticelli MG. A cost-conscious approach to the evaluation of patients with chronic back pain. Hawaii Med J. 1986;45:447–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]