Abstract

Objective

To explore reasons for clinical inertia in the management of persistent depression symptoms.

Research Design

We characterized patterns of treatment adjustment in primary care and their relation to the patient’s clinical condition by modeling transition to a given treatment “state” conditional upon the current state of treatment. We assessed associations of patient, clinician, and practice barriers with adjustment decisions.

Subjects

Survey data on patients in active care for major depression was collected at six-month intervals over a two-year period for the Quality Improvement for Depression (QID) studies.

Measures

Patient and clinician characteristics were collected at baseline. Depression severity and treatment were measured at each interval.

Results

Approximately one-third of the observation periods ending with less than a full response resulted in an adjustment recommendation. Clinicians often respond correctly to the combination of severe depression symptoms and less than maximal treatment by changing the treatment. Appropriate adjustment is less common, however, in management of less severely depressed patients who do not improve after starting treatment, particularly if their care already meets minimal treatment intensity guidelines.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that quality improvement efforts should focus on promoting appropriate adjustments for patients with persistent depression symptoms, particularly those with less severe depression.

Keywords: Depression, Clinical inertia, Evidence-based medicine, Physician practice patterns

INTRODUCTION

Standard clinical paradigms instruct clinicians to initiate treatments that have the greatest probability of success, observe for target symptom response and side effects, and readjust accordingly. Studies show, however, that clinical inertia, characterized as a failure to appropriately modify treatment, is prevalent among clinicians, particularly for conditions with less acute symptoms.1

Depression is a prevalent, disabling condition for which initial treatments often fail to achieve results and/or cause troublesome side effects.2 Successful depression treatment, therefore, requires clinicians to actively monitor symptoms and adjust treatments accordingly. Yet, as for other conditions, clinical inertia may be prevalent among clinicians treating depression.3,4 Avoidable illness days and reduced work productivity experienced by depressed patients due to clinical inertia can substantially lower the value realized from the resources invested in depression treatment by insurers, employers, families and patients.

We know little about factors associated with clinical inertia. Studies examining the management of patients with diabetes and hypertension found that disease severity, therapy intensity, and competing demands predict treatment adjustment.5–7 Other studies suggest that clinical inertia is associated with practice-related factors such as visit length; provider-related factors such as skill, education, and use of “soft reasons” to avoid therapy intensification; and patient-related factors such as concern about side effects.1,8 While it is likely that some non-responding patients with depression require a “go slow” approach, data on the benefits of treatment intensification suggest that active clinician response to continued symptoms is warranted in most cases.

This study supports efforts to improve the value of depression treatments by advancing our understanding of the factors associated with clinical inertia in depression treatment. We describe the frequency of treatment adjustment and identify factors associated with carrying out adjustments. Consistent with models of healthcare provider behavior and the clinical inertia literature, we investigate the provider, patient, and practice characteristics that might affect clinician predisposition to continue ineffective care.9

METHODS

Data

We used data from the Quality improvement For Depression (QID) collaboration. The collaboration consisted of four cluster-randomized experiments evaluating the implementation of collaborative care model-based interventions10 to improve the care and outcomes of depressed patients in primary care practices. Studies used similar self-report survey instruments to measure patient characteristics, care, symptoms, and outcomes at baseline, six, 12, 18 and 24 months. Practices were randomized to intervention or usual care conditions using a block randomization design. Previous research conducted on the QID found that the intervention significantly improved quality of care and outcomes.11–13

Patients who screened positive for depression during prespecified enrollment windows were invited to join in the study if they planned to receive care in the clinic on an ongoing basis and if they met the inclusion criteria. Individuals already receiving depression care were eligible. Three of the four studies only included patients with health insurance coverage. All patients in the combined sample met the DSM-IV criteria for major depression at the time of enrollment.

Clinicians completed a questionnaire at baseline that included questions about training, depression care expertise, and barriers to providing care, as previously described.14,15

For the analyses presented here, we included only patients with a baseline survey and at least one six-month observation period preceded and followed by a survey. To ensure that all patients analyzed had had the opportunity to have their treatments adjusted, we included only patients who received “active care.” We defined “active care” as two consecutive six-month periods with at least one reported primary care visit in which mental health issues were discussed or one mental health specialist visit; patients receiving antidepressants without visits were excluded. Our study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Harvard Medical School.

Independent variables

Depression symptom severity

Study investigators used the modified Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (mCES-D) to measure depression symptom severity at the end of each observation period. Clinicians did not have access to the scores. The mCES-D is an adapted version of the CES-D that closely reflects DSM-IV depression symptoms.15–17 Scores above 20 on the 100-point mCES-D scale indicate the depressed range which is equivalent to a cutoff point of 16 on the CES-D.18 For several models, we transformed the mCES-D score into a linear spline with two knots placed at terciles of the score.

Depression symptom improvement

According to depression treatment guidelines,19 if patients do not experience significant symptom improvement, defined as a 50% or greater reduction in symptoms, clinicians should adjust their treatment.20 If patients do experience symptom improvement, clinicians should continue treatment through remission and beyond to reduce the risk of relapse.2,20–22 Following these guidelines, we created a response to treatment measure as defined by Fava and Davidson23 to assess the extent to which clinicians adjusted treatment appropriately. A difference between the start and end of the observation period mCES-D score of 50% or more or an end mCES-D score below the depression cutoff point of 20 constituted full response; an improvement of 25% to less than 50% constituted partial response, and worsening or an improvement of less than 25% constituted non response.

We used the continuous measure of change in mCES-D to measure depression symptom improvement instead of response category for all stratified analyses.

Patient initial treatment state

For each observation period we characterized the treatment patients received using information collected in the patient survey at the end of the interval (see Appendix Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/A992). We defined four mutually exclusive active treatment states:

Primary care only: Patients who reported at least one visit with a primary care clinician in which mental health issues were discussed, no medication for personal/emotional issues, and no visits to a mental health specialist.

Primary care-supported antidepressants: Patients who reported at least one visit with a primary care clinician in which mental health issues were discussed, medication for personal/emotional issues, and no visits to a mental health specialist.

Mental health specialist treatment without medications: Patients who reported at least one visit with a mental health specialist and no medications for personal/emotional issues.

Combined medication/mental health treatment: Patients who reported at least one visit with a mental health specialist and medication for personal/emotional issues.

The combined medication/mental health treatment is the most intense treatment state while primary care only is the least intense treatment state. We do not distinguish between the intensity of treatment of the two middle-intensity treatment states.

Patient treatment experience

We assessed receipt of adequate care, experience of side effects, and self-discontinuation of treatment during each six-month observation period. We defined adequate treatment as completion of four visits to a mental health specialist or at least 60 days of antidepressants received at or above the minimum effective dose as outlined in Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) guidelines during the six-month period.11 We defined side effects for those taking an antidepressant during the observation period as patient report of one of twelve side effects to a ‘moderate’ or ‘severe’ degree: drowsy, nausea/upset stomach, difficulty urinating, dizziness, sexual problems, dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, changes in appetite, weight gain, insomnia, anxiety. We defined self-discontinuation of treatment as patient report of therapy discontinuation without clinician recommendation.

Patient comorbidities

We measured the presence of 14 comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, asthma, cancer, neurological condition, stroke, heart failure, coronary artery disease, back problems, irritable bowel disorder, thyroid disease, kidney failure, and eye disease) and the number of comorbidities at baseline. We measured physical health functioning during each observation period with the physical health composite score (PCS-12) of the MOS Short Form 36 scale.24 We measured co-occurring dysthymic disorder at baseline based on the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview for dysthymia.25

Patient socio-demographics

Employment status, age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, health insurance (insured, Medicare, or Medicaid) and social support were measured through self-report at baseline. The social support measure was a short form of the MOS social support survey.26

Clinician characteristics and practice barriers

Primary care clinician specialty (internal medicine, family/general practice, or non-MD practitioner), skill, and participation in depression quality improvement efforts were reported at baseline in the clinician questionnaire. Survey batteries were previously tested for reliability and validity or developed specifically for the QID study and have been used in previous research.14,27,28 Depression skill was measured in four areas (counseling/education, diagnosis, medication, and referral) on a four-point scale. Scale responses ranged from not at all skilled to very skilled. Participation in depression quality improvement was measured in two ways: if the clinician worked in a practice randomized to the QID intervention arm and hours of clinician participation in mental health quality assurance in the past year.

Clinicians reported five practice barriers at baseline: difficulty obtaining preferred medications, limited availability of mental health professionals, limited time for counseling/education, limited time for follow-up, and poor reimbursement. Clinicians were asked how much each barrier limited their ability to provide “optimal” depression care, on a three-point scale.

Dependent variable

Clinician treatment adjustment recommendation

We defined treatment adjustment as a patient-reported recommendation from a primary care clinician or mental health specialist for a new or modified therapy during the subsequent patient observation period. Among patients in the primary care-only treatment state, an adjustment recommendation consisted of clinician recommendation for an antidepressant or referral in the subsequent observation period. Among patients on primary care-supported antidepressants, adjustment consisted of either a change in antidepressant or mental health specialist referral. Among patients receiving mental health specialist treatment without medications, adjustment consisted of either starting an antidepressant or referral to a different mental health specialist. Among patients in combination therapy, adjustment consisted of either a change in antidepressant or referral to a new mental health specialist. We did not include recommendations to discontinue a treatment, when not accompanied by different or additional treatments as defined above, as treatment adjustments.

Analyses

We conducted longitudinal analyses with Stata v.9 statistical software29 using patient observation periods as the unit of analysis. We used random effects logistic regression models to account for repeated patient observations,30 specifying the within-group correlation structure as exchangeable and applying robust standard error estimates (the Huber/White “sandwich” estimator) to further account for clustering of observations.31 In models with multiple predictors, we calculated the variance inflation factor to assess collinearity and used backward elimination to determine whether removing correlated variables revealed the significance of key predictors. Data from patients whose clinician did not respond to the survey were omitted in the estimation of models that included clinician covariates, but to maximize power were not omitted in the estimation of models which do not include these covariates. Models estimated with patient discontinuation-of-therapy variables omitted observations that required data collected at baseline as therapy discontinuation was not assessed at that time period. All models included dummy variables for each QID study to control for regional effects and any unmeasured study design heterogeneity.

To describe our sample, we measured patient characteristics, depression severity, treatment history, and adjustment recommendation by category of depression symptom improvement.

We estimated four sets of models to understand the factors associated with adjustment recommendation. In the first set, we examined the effect of depression symptom improvement on adjustment by estimating the association between partial and non response and subsequent adjustment recommendation. We added depression severity, patient treatment state, and all other patient variables in an adjusted model. We re-estimated the adjusted model limiting the sample to observations with individuals ending with “moderate” severity. We did this because level of severity at the end of the observation period can be confounded with changes in severity during the observation period. For example, patients at a high value of current severity could not have improved much since the previous observation period, so current high severity and worsening of symptoms were confounded. Patients with “moderate” symptoms could have changed in either direction during the observation period.

In the remaining models, we limited the sample to patient observation periods characterized by partial and non response to isolate factors associated with appropriate adjustment since adjustments following full response may or may not be appropriate. In the second set, we estimated the influence of all patient factors including depression symptom improvement, depression symptom severity, treatment state, treatment experience, comorbidities, and socio-demographics on appropriate adjustment recommendation. Then, we added clinician characteristics and practice barriers and reestimated the models. In the third and fourth model sets, we stratified by treatment state and type of adjustment recommendation, respectively. Since we had limited power in the stratified models, we did not include measures for each comorbid condition. We also did not include variables that were logically irrelevant for that model such as side effects in the primary care only model. In the fourth set, we excluded observations for which the corresponding type of adjustment was not a meaningful option.

To address the possibility that patients treated by mental health providers are systematically different from primary care only patients, we compared these groups on observable variables and estimated models stratified by type of provider. Further, we estimated models excluding observations with non-MD mental health specialist visits only because these providers may have less flexibility to make adjustment recommendations.

RESULTS

Descriptive analysis

Our cohort is described in Table 1. We excluded 1437 observation periods not paired with a prior observation period, 1072 without complete patient information, and 2859 without active treatment, leaving 1821 observation periods representing 561 unique patients. The high proportion of insured was expected due to the insurance requirement specified by three of the QID studies. The proportion of males was lower than in the full dataset because males were less likely to meet the criteria for active care than women. Models including clinician variables were fitted with 1327 observations after excluding data for patients whose clinician did not complete the baseline survey.

Table 1. Description of sample.

| Observation periods ending in Full Response Symptom improvement >50% |

Observation periods ending in Partial Response Symptom improvement 25%–50% |

Observation periods ending in No Response Symptom improvement <25% |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Percent or Mean (SD) | Percent or Mean (SD) | Percent or Mean (SD) | |

| Adjustment recommendation** | |||

| 58% | 66% | 67% | |

| Demographic information | |||

| Male | 28% | 28% | 28% |

| Married | 41% | 47% | 47% |

| Work full/part-time | 62% | 65% | 67% |

| Unemployed, looking | 5% | 3% | 4% |

| Unemployed, health | 9% | 13% | 9% |

| Retired | 9% | 7% | 8% |

| Other | 16% | 11% | 13% |

| Less than high school | 15% | 11% | 12% |

| High school graduate | 35% | 41% | 34% |

| Some college | 40% | 39% | 44% |

| College graduate | 10% | 9% | 10% |

| Any health insurance | 95% | 95% | 95% |

| Medicare** | 9% | 16% | 11% |

| Medicaid | 12% | 8% | 12% |

| Age 18–34 | 26% | 24% | 27% |

| Age 35–49 | 40% | 42% | 40% |

| Age 50–65 | 26% | 27% | 26% |

| Age 66+ | 8% | 7% | 8% |

| White | 69% | 76% | 70% |

| Hispanic | 13% | 12% | 11% |

| Black | 9% | 9% | 10% |

| Other | 9% | 3% | 9% |

| Comorbid conditions and physical health | |||

| Comorbidities - none | 18% | 20% | 25% |

| One | 30% | 28% | 25% |

| Two | 21% | 22% | 18% |

| Three or more | 31% | 30% | 32% |

| Physical functioning (low to high)** | 47.0 (10.6) | 41.8 (12.2) | 40.3 (12.1) |

| Social support (low to high) | 31.2 (9.1) | 30.7 (9.1) | 31.0 (9.1) |

| Dysthymia | 16% | 21% | 17% |

| Depression severity and treatment state | |||

| mCES-D score** | 14.1 (9.8) | 38.4 (9.7) | 58.2 (17.9) |

| Primary care only** | 26% | 32% | 34% |

| Antidepressant | 7% | 12% | 9% |

| Mental health specialist | 47% | 39% | 40% |

| Antidepressant & mental health specialist | 20% | 18% | 17% |

| N | 539 | 236 | 1048 |

Differences between groups assessed with chi2 test

p<0.05,

p<0.01

- Primary care only: PCP visit(s), no antidepressant, and no mental health specialist visit(s).

- Antidepressant: PCP visit(s), antidepressant, and no mental health specialist visit(s).

- Mental health specialist: Antidepressant, no mental health specialist visit(s).

- Antidepressant & mental health specialist: Antidepressant and mental health specialist visit(s).

Twenty-nine percent of the observation periods ended with full response to treatment (>50% symptom improvement), 13% partial response (25%–50% symptom improvement), and 58% non response (<25% symptom improvement). Sixty-four percent of the observation periods resulted in an adjustment recommendation.

There were no significant differences across response groups in any of the demographic characteristics, comorbid conditions, dysthymia, or social support. Observation periods ending in non response and partial response were associated with worse physical health functioning and higher rates of Medicare. Observation periods ending with full response were characterized by more intense depression treatment and less severe depression at the end of the period than the other two response categories.

We found few differences between patients cared for by a mental health provider and patients seeing a primary care provider only. The former were more likely to be male, have co-occurring dysthymia, and have health insurance at baseline. Twenty percent of those cared for by a mental health provider saw a psychiatrist.

The influence of depression symptom improvement on adjustment recommendation

According to depression treatment guidelines, clinicians should adjust the treatment of patients who do not achieve full response. Without controlling for any other variables, observation periods characterized by partial and non response were significantly more likely to be associated with a subsequent adjustment recommendation then those characterized by full response (Table 2, Model 1). Response category was no longer significant, however, after adjusting for depression severity, treatment state, and patient covariates (Table 2, Model 2). Treatment state and severity were significantly associated with adjustment recommendations.

Table 2. The influence of depression symptom improvement on adjustment recommendation.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Full Sample, Unadjusted |

Full Sample, Adjusted |

Moderate Severity Only, Adjusted |

||||

| Independent variables | Coefficient | (p-value) | Coefficient | (p-value) | Coefficient | (p-value) |

| Depression symptom change, | ||||||

| Reference group = observation periods ending with full response | ||||||

| Partial response | 0.347 | (<0.01) | 0.298 | (0.11) | 0.317 | (0.10) |

| No response | 0.402 | −0.044 | −0.126 | |||

| Depression severity | ||||||

| Low, mCES-D score (0–29) | 0.003 | (<0.01) | (<0.01) | |||

| Moderate, mCES-D score (30–55) | 0.010 | |||||

| High, mCES-D score (56–100) | 0.022 | |||||

| Depression treatment | ||||||

| Treatment state, Reference group =primary care only | ||||||

| Antidepressant | −1.227 | (<0.01) | −0.849 | (<0.01) | ||

| Mental health specialist | −0.415 | 0.044 | ||||

| Antidepressant & mental health specialist | −1.749 | −1.757 | ||||

Dependent variable = Adjustment recommendation; Coefficient estimates and p-values from t and F tests displayed.

Source: QID Core sample, unit of analysis is observation period, excludes observations not in active treatment.

Clusters/mean observations per cluster = 943/1.9 (models 1,2); 491/1.3 (model 3).

- Partial response: mCES-D score improved between 25% and 50% during observation period

- Non-response: mCES-D score improved by less than 25% during observation period

Adjusted models include all patient covariates. QID study indicators included in all models.

- Primary care only: PCP visit(s), no antidepressant, and no mental health specialist visit(s).

- Antidepressant: PCP visit(s), antidepressant, and no mental health specialist visit(s).

- Mental health specialist: Antidepressant, no mental health specialist visit(s).

- Antidepressant & mental health specialist: Antidepressant and mental health specialist visit(s).

If depression symptom improvement does influence clinician adjustment decisions, it should be most apparent in a model limited to observations ending with mCES-D scores in the moderate severity range as this group experienced the full range of responses (Table 2, Model 3). Patients with moderate severity at the end of the observation period whose depression symptoms worsened, however, were no more likely to receive an adjustment recommendation than patients whose depression symptoms improved during the observation period, confirming our findings from the full sample that symptom change does not affect adjustment decisions.

The influence of patient, clinician, and practice factors on appropriate adjustment recommendation

Depression severity and less intense treatment were significant predictors of appropriate treatment adjustment (Table 3). Compared to patients in the primary care-only treatment state, individuals on antidepressants and/or seeing a mental health specialist were less likely to receive an adjustment recommendation. Adjustment recommendation was not related to degree of symptom improvement, adequate care, self-discontinuation of treatment, comorbid conditions, or any of the patient socio-demographic characteristics. Of the clinician factors, general/family medicine specialty, higher skill, and fewer barriers to preferred medications significantly positively predicted appropriate adjustment recommendation. Clinician sex, years in practice, mental health QA hours, and the other four practice barriers were not significantly related to appropriate adjustment.

Table 3. The influence of patient, clinician, and practice factors on appropriate adjustment recommendation.

Sample limited to observation periods characterized by partial or non response

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | Coefficient | (p-value) | Coefficient | (p-value) |

| Depression symptom improvement | ||||

| mCES-D change | −0.002 | (0.60) | −0.002 | (0.51) |

| Depression severity | ||||

| Low, mCES-D score (0–29) | 0.025 | (0.07) | 0.066 | (0.06) |

| Moderate, mCES-D score (30–55) | −0.001 | 0.000 | ||

| High, mCES-D score (56–100) | 0.034 | 0.024 | ||

| Treatment state (Reference group primary care only) | ||||

| Antidepressant | −1.418 | (<0.01) | −1.534 | (<0.01) |

| Mental health specialist | −0.290 | −0.519 | ||

| Antidepressant & mental health specialist | −2.015 | −2.044 | ||

| Treatment experience | ||||

| Stopped antidepressant prematurely | 0.225 | (0.42) | ||

| Stopped counseling prematurely | −0.208 | (0.52) | ||

| Received adequate treatment | −0.061 | (0.79) | ||

| Comorbidities* / other health conditions | ||||

| No. of comorbidities | 0.000 | (0.98) | −0.004 | (0.53) |

| Physical health functioning (low to high) | −0.418 | (0.58) | 0.026 | (0.64) |

| Dysthymia | −0.215 | (0.45) | −0.205 | (0.30) |

| Patient socio-demographics | ||||

| Male | −0.161 | (0.52) | −0.170 | (0.38) |

| Married | 0.013 | (0.95) | −0.027 | (0.87) |

| Social support (low to high) | 0.002 | (0.89) | 0.008 | (0.36) |

| Work status, Reference group = full or part time | ||||

| Unemployed, looking | 0.553 | (0.65) | −0.237 | (0.54) |

| Unemployed, health reasons | −0.332 | −0.358 | ||

| Retired | 0.343 | 0.420 | ||

| Other | 0.042 | −0.003 | ||

| Education | 0.045 | (0.33) | 0.065 | (0.09) |

| Health insurance | −0.661 | (0.09) | −0.617 | (0.06) |

| Medicare | −0.268 | (0.44) | −0.158 | (0.55) |

| Medicaid | −0.021 | (0.94) | 0.043 | (0.86) |

| Age | −0.004 | (0.69) | −0.001 | (0.94) |

| Race/Ethnicity, Reference group = white | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.593 | (0.29) | 0.327 | (0.74) |

| Black | 0.501 | 0.081 | ||

| Other race/ethnicity | −0.162 | 0.046 | ||

| Clinician characteristics and practice barriers | ||||

| Male primary care clinician | −0.273 | (0.18) | ||

| Yrs in practice | −0.006 | (0.55) | ||

| Internal medicine (Reference group = General/Family Medicine | −0.519 | (0.04) | ||

| Non-MD | −0.436 | (0.29) | ||

| Skill in depression | 0.100 | (0.05) | ||

| No. hrs/past yr mental health quality improvement | 0.002 | (0.90) | ||

| Intervention group | 0.023 | (0.90) | ||

| Practice barriers | ||||

| Limited access to mental health professionals | 0.143 | (0.31) | ||

| Preferred medications difficult to obtain | −0.396 | (0.01) | ||

| Limited time for counseling/education | 0.068 | (0.70) | ||

| Inadequate time for follow-up | −0.017 | (0.92) | ||

| Inadequate reimbursement | −0.272 | (0.08) | ||

Dependent variable = Adjustment recommendation; Coefficient estimates (β) and p values displayed.

Source: QID Core sample, unit of analysis is observation period, excludes observations not in active treatment and observations ending in full response. Clusters/mean observations per cluster = 409/1.3 (model 1); 587,1.6 (model 2).

Models 1 and 2 differ by included covariates. QID study indicators included in both models.

Model 1 included an indicator for each comorbidity: diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, asthma, cancer, neurological conditions, stroke, heart failure, angina or coronary artery disease, back problems, irritable bowel disorder, thyroid disease, and eye disease. None were significant. Kidney failure was removed from the model due to small sample size.

- Primary care only: PCP visit(s), no antidepressant, and no mental health specialist visit(s).

- Antidepressant: PCP visit(s), antidepressant, and no mental health specialist visit(s).

- Mental health specialist: Antidepressant, no mental health specialist visit(s).

- Antidepressant & mental health specialist: Antidepressant and mental health specialist visit(s).

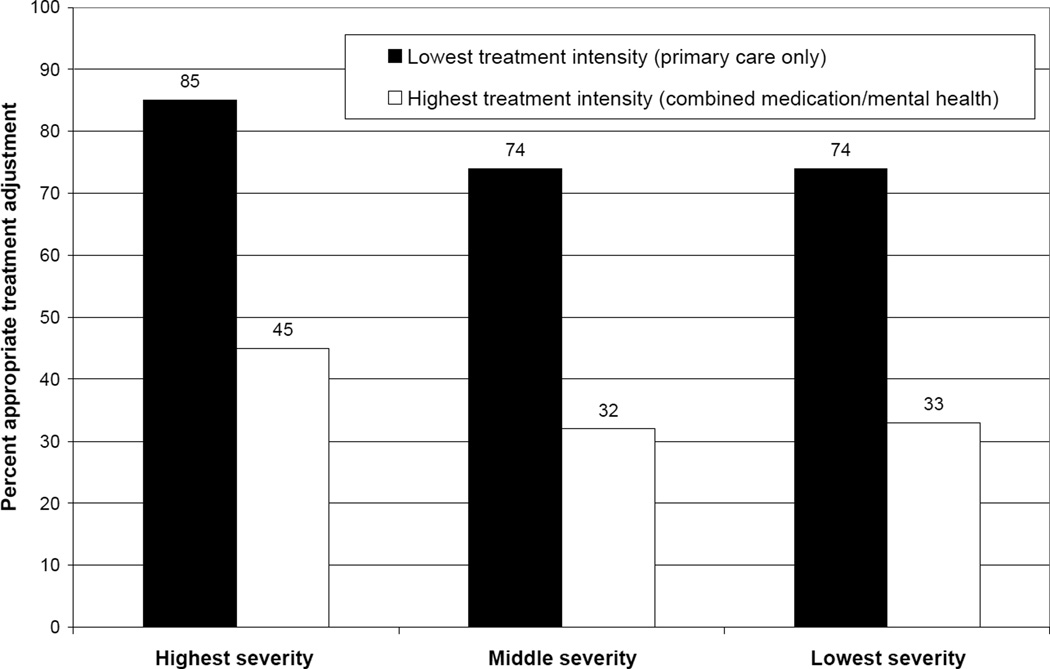

Figure 1 illustrates the strong impact of depression severity and treatment state on appropriate adjustment. Patients in the lowest treatment intensity state receive treatment adjustments at a rate double that of patients in the highest treatment intensity state. Further, regardless of treatment intensity, patients with higher depression scores had the highest rates of treatment adjustment.

Figure 1. Rate of appropriate treatment adjustment by depression severity and treatment intensity*.

* Sample limited to observation periods classified as partial or non response.

When we stratified the analysis by treatment state and adjustment type, results were similar to unstratified models (Appendix Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/A993, and Appendix Table 3, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/A994). Adjustment recommendation tended to be associated with depression severity but not related to degree of symptom improvement, adequate care, self-discontinuation of treatment, comorbid conditions, or patient socio-demographic characteristics. In the model limited to observation periods in which antidepressants were used, two side effects, difficulty urinating and dizziness/lightheadedness, predicted adjustment recommendation. In the model predicting antidepressant adjustment, one side effect significantly predicted no adjustment recommendation: feeling anxious or jumpy. Several clinician characteristics and practice barriers were negatively related to adjustment in the stratified models but significance varied by model.

Stratifying the analysis by type of provider and limiting models to patients seeing MDs did not alter main results. Although we found significant levels of multicollinearity in models with multiple predictors, removing correlated variables from models one at a time did not change our findings.

CONCLUSIONS

This study found that a two-thirds majority of observation periods ending with less than a full response were offered a treatment adjustment. However, in adjusted analyses we found patients with worsening severity were no more likely to receive an adjustment recommendation than patients who were improving. Similar to studies examining factors associated with appropriate adjustment for patients with diabetes and hypertension, we found severity and treatment intensity are important predictors of adjustment.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report rates of treatment adjustment recommendations for depression that includes a range of modalities (ie referral, antidepressant adjustment, new antidepressant). Studies concentrating on one modality, such as antidepressant adjustments, are likely to find lower rates.

The association between severity and adjustment recommendation is a signal of appropriate care: Patients with greater severity have the most immediate clinical need for symptom relief. Further, the association between less intense treatment and adjustment signifies that clinicians correctly ramp up the treatment of those whose care meets minimal treatment intensity guidelines. Patients receiving multi-modal depression care, however, were less likely to receive an appropriate adjustment recommendation. This may be a result of fewer remaining adjustment options, particularly for treatment-resistant patients who may have attempted multiple therapies already. Clinicians should be aware that there are effective treatment options for all patients, which include augmenting or switching medications and alternative evidence-based psychotherapies, regardless of whether previous treatments have failed. Lack of coordination between primary care and mental health specialists may also be a factor as non-prescribing mental health specialists, such as psychologists or social workers, may need to work with primary care to effect medication treatment adjustments.

There is no objective measure of severity for depression akin to a blood pressure reading for hypertension or a blood test for diabetes. As a result, the failure to intensify therapy in depression management may reflect lack of recognition of persistent depression symptoms rather than a failure to act on information collected. Indeed, videotapes of primary care patient-physician interactions show that communication about mental health, including severity assessment, is limited to two minutes on average.32 As a result, clinicians may be more likely to respond to the current severity of depression, something that is easier to judge, than the patients’ change in severity.

Enhanced monitoring of changes in severity of depression may be accomplished through more frequent contact with patients. Although depression treatment guidelines recommend that patients be seen every one to two weeks during the acute treatment phase, this target is rarely met.33 Patient contact through various methods including the telephone or e-mail by the physician or care manager, can facilitate symptom monitoring while taking less time and resources than face-to-face contact. Routine administration of standardized symptom assessment scales such as the CES-D and the briefer PHQ-9 can also enhance severity monitoring.34 The PHQ-9 has been validated to assess severity changes35 and can be self-administered by patients or administered by care managers. Comparing standardized summaries of patients’ self-reported severity scores over time may improve clinicians’ detection of severity changes over ad hoc clinical observations, and, if linked with increased rates of appropriate treatment, holds the promise of improving depression outcomes.

Our finding that practice barriers, in particular limited access to preferred medications and limited reimbursement, affect adjustment recommendations suggests that reducing these barriers may be beneficial. System changes such as providing reimbursement for all aspects of depression care including phone calls and/or e-mails and facilitating follow-up care through care managers and electronic registries to reduce clinical burden have been heralded by many for improving the quality of depression care,36–38 and may be particularly helpful for improving rates of appropriate treatment adjustment. Encouraging health plans not to use formularies that require prior authorization may also improve care as they may deter clinicians from prescribing a different brand if the initial choice has not been effective.

The association of clinician training with patterns of adjustment recommendations suggests providing more clinician education may improve rates of appropriate adjustment recommendations. Depression education has been previously found to improve depression treatment, although long-term improvement may require concurrent system changes to be sustainable.39 Our finding that patients of non-physician practitioners are less likely to be offered antidepressant adjustment recommendations than patients of clinicians who have medical degrees is sensible given the limited prescription power of non-physician practitioners. Enhancing communication within physician/non-physician teams and providing psychiatrist consultation for non-physicians may improve appropriate antidepressant adjustments.

We found little evidence that patient characteristics consistently predicted adjustment recommendations. This was somewhat surprising as we expected clinicians may be more responsive to severity change for patient groups known to experience better patient-provider communication such as females, whites, and more educated patients.40–46 We had also expected that the presence of comorbid conditions would influence the likelihood of adjustment since they are associated with competing demands during visits, an alternative explanation for clinical inertia.6,47 However, we did not find this to be the case. Since we limited our sample to patients receiving at least one mental health visit in two consecutive six-month observation periods, it is possible that patients with comorbid conditions whose depression received less attention were excluded from our analysis.

There are several limitations to this study. First, patient self-reports of treatment and adjustment recommendations may be inaccurate. However, self-report may be the best way to gather comprehensive data on treatments received in a variety of settings for stigmatized conditions such as depression, especially because adjustment recommendations may not be consistently recorded in medical charts. Further, patient recollection of prescription medication advice has been found to be over 90% accurate.48 Our reliance on clinician self-report to measure skill may lead the variable to reflect a combination of valid self-assessments and attitudes (presumably more positive) toward getting engaged with care for depression. Second, we examined adjustment recommendations rather then implementation of adjustments. We opted to study the former as we were interested in factors associated with clinician decision-making regarding adjustments rather than patient fulfillment of recommendations. Third, we used data collected at six-month intervals, but depression severity may have fluctuated within each interval. Clinicians observing the patient in between these intervals may have made adjustment recommendations in response to changes in severity unobservable to us. However, using six-month intervals allowed for a generous timeframe for clinicians to make a decision that a patient was not improving and make an adjustment recommendation. Measuring adjustment decisions associated with severity change within a shorter interval of time may be unrealistic in today’s practice environment as clinicians may not be able to see patients as frequently as recommended by clinical guidelines.

Our study results, robust to numerous sensitivity analyses, raise concerns about physician recognition and management of persistent depression symptoms. Interventions that help physicians identify and respond to continued symptoms in a timely manner are needed to improve the quality of care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (F31MH75719; R01 MH068260).

References

- 1.Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:825–834. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1243–1252. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hepner KA, Rowe M, Rost K, et al. The effect of adherence to practice guidelines on depression outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:320–329. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-5-200709040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trivedi MH, Daly EJ. Measurement-based care for refractory depression: a clinical decision support model for clinical research and practice. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(Suppl 2):S61–S71. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guthrie B, Inkster M, Fahey T. Tackling therapeutic inertia: role of treatment data in quality indicators. BMJ. 2007;335:542–544. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39259.400069.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parchman ML, Pugh JA, Romero RL, et al. Competing demands or clinical inertia: the case of elevated glycosylated hemoglobin. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:196–201. doi: 10.1370/afm.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grant RW, Cagliero E, Dubey AK, et al. Clinical inertia in the management of Type 2 diabetes metabolic risk factors. Diabet Med. 2004;21:150–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Connor PJ. Overcome clinical inertia to control systolic blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2677–2678. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.22.2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubenstein LV, Mittman BS, Yano EM, et al. From understanding health care provider behavior to improving health care: the QUERI framework for quality improvement. Quality Enhancement Research Initiative. Med Care. 2000;38:I129–I141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Stepped collaborative care for primary care patients with persistent symptoms of depression: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:1109–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wells K, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Five-year impact of quality improvement for depression: results of a group-level randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:378–386. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubenstein LV, Parker LE, Meredith LS, et al. Understanding team-based quality improvement for depression in primary care. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:1009–1029. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.63.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, et al. Improving depression outcomes in community primary care practice: a randomized trial of the quEST intervention. Quality Enhancement by Strategic Teaming. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:143–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meredith LS, Jackson-Triche M, Duan N, et al. Quality improvement for depression enhances long-term treatment knowledge for primary care clinicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:868–877. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.91149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rost KM, Duan N, Rubenstein LV, et al. The Quality Improvement for Depression collaboration: general analytic strategies for a coordinated study of quality improvement in depression care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:239–253. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(01)00157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. J Appl Psychol Measur. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherbourne CD, Wells KB, Duan N, et al. Long-term effectiveness of disseminating quality improvement for depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:696–703. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.7.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orlando M, Sherbourne CD, Thissen D. Summed-score linking using item response theory: application to depression measurement. Psychol Assess. 2000;12:354–359. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services PHS. Depression Guideline Panel. Rockville, MD: AHCPR; 1993. Depression in Primary Care: Volume 2. Treatment of Major Depression. Clinical Practice Guideline. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:28–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1231–1242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schatzberg AF, Rush AJ, Arnow BA, et al. Chronic depression: medication (nefazodone) or psychotherapy (CBASP) is effective when the other is not. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:513–520. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fava M, Davidson KG. Definition and epidemiology of treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1996;19:179–200. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. Composite International Diagnostic Interview for Primary Care, Version 2.0. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meredith LS, Rubenstein LV, Rost K, et al. Treating depression in staff-model versus network-model managed care organizations. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:39–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00279.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meredith LS, Cheng WJ, Hickey SC, et al. Factors associated with primary care clinicians' choice of a watchful waiting approach to managing depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:72–78. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.StataCorp. Version 9. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hardin J, Hilbe J. Generalized estimating equations. Boca Raton, Florida: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams R. A note on robust variance estimation for cluster-correlated data. Biometrics. 2000;56 doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tai-Seale M, McGuire TG, Zhang W. Time allocation in primary care office visits. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:1871–1894. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00689.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Committee for Quality Assurance. The State of Health Care Quality 2006. Washington, DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance; 2006. Antidepressant Medication Management; pp. 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lowe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, et al. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) J Affect Disord. 2004;81:61–66. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katon WJ. The Institute of Medicine "Chasm" report: implications for depression collaborative care models. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25:222–229. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(03)00064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frank RG, Huskamp HA, Pincus HA. Aligning incentives in the treatment of depression in primary care with evidence-based practice. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:682–687. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.5.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eisenberg L. Treating depression and anxiety in the primary care setting. Health Aff (Millwood) 1992;11:149–156. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.11.3.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin EH, Katon WJ, Simon GE, et al. Achieving guidelines for the treatment of depression in primary care: is physician education enough? Med Care. 1997;35:831–842. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199708000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balsa AI, McGuire TG, Meredith LS. Testing for statistical discrimination in health care. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:227–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00351.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hall JA, Roter DL. Patient gender and communication with physicians: results of a community-based study. Womens Health. 1995;1:77–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hall JA, Roter DL, Katz NR. Meta-analysis of correlates of provider behavior in medical encounters. Med Care. 1988;26:657–675. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, et al. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2084–2090. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pendleton DA, Bochner S. The communication of medical information in general practice consultations as a function of patients' social class. Soc Sci Med. 1980;14A:669–673. doi: 10.1016/0160-7979(80)90072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Willems S, De Maesschalck S, Deveugele M, et al. Socio-economic status of the patient and doctor-patient communication: does it make a difference? Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGuire TG, Ayanian JZ, Ford DE, et al. Testing for Statistical Discrimination by Race/Ethnicity in Panel Data for Depression Treatment in Primary Care. Health Serv Res (OnlineEarly Articles) 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00770.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stange KC. Is 'clinical inertia' blaming without understanding? Are competing demands excuses? Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:371–374. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kravitz RL, Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, et al. Recall of recommendations and adherence to advice among patients with chronic medical conditions. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:1869–1878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.