Abstract

Parent–child relationships are fundamental human relationships in which specific norms govern proper parent–child interactions. Such norms, or filial ethics, have been observed in different cultures, including in the United States and Taiwan, but important differences may exist in how filial practices are viewed across cultures. From a traditional view of power as domination over others, if filial relationships are viewed to reflect power differentials between parents and children, actors who follow filial ethics should be viewed as less powerful than actors who do not follow filial ethics for maintaining or enhancing positive parent–child relationships. Alternatively, power can be conceptualized as the ability to meet one’s needs (e.g., for communal care and trust), and actors who follow filial ethics should be viewed as more powerful and trustworthy than actors who do not follow filial ethics because they have the ability to maintain or enhance positive parent–child relationships. Based on a power–trust model, we compared American and Taiwanese perceptions of actors in an experiment using vignettes describing filial behaviours. We conducted a path analysis with a sample of 112 American and 74 Taiwanese participants to test the proposed relations. Results showed that both Taiwanese and Americans rated actors more favourably (i.e., as more powerful and trustworthy) when actors behaved according to filial ethics than when they did not. Some cross-cultural differences were also observed: Taiwanese attributed trust-traits to actors who performed filial practices to a larger degree than did Americans. We discuss implications for the implicit nature of filial relationships and conceptualization of power cross-culturally.

Keywords: Filial ethics, Cross-cultural, Powerfulness, Trustworthiness, Parent–child relationships

Social psychologists have found evidence suggesting that we tend to evaluate others based on their behaviour, perceiving behaviour as indicative of personality rather than the situation—a tendency referred to as “dispositionism ”(e.g., Ross & Nisbett, 1991), “fundamental attribution error” (Ross, 1977), or “correspondence bias” (Gilbert & Malone, 1995). One reason we do so may be a motivation to feel competent in navigating our social spheres (Schüler, Sheldon, & Fröhlich, 2009). For example, perceiving others on dispositional traits such as anxiety or aggressiveness informs how doctors prescribe treatment (e.g., Ong, De Haes, Hoos, & Lammes, 1995) and jurors decide a verdict (Sommers & Ellsworth, 2000). Importantly, trait judgments also provide relational information. That is, they offer relational “clues” for how to interact with others or what type of relationship may be possible. Because social relationships are considered to be at the core of society, societies have developed norms by which to organize and construe social relationships and evaluate our and others’ social behaviour (Fiske, 1993). One such behaviour guided by relational norms is filial practices toward one’s parents.

In many cultures, behaviour toward one’s parents is particularly meaningful. In East Asian societies, children’s behaviour toward parents may be evaluated in terms of filial ethics, a set of behavioural prescriptions and a socialization goal (Ho, 1994). Elaborated by Confucianism, filial ethics refers to specific rules governing proper behaviour between parents and children and emphasizes relational obligation (Yeh & Bedford, 2003). Confucianism holds that, through proper interactions, individuals learn to respect and submit to authority figures (e.g., parents), and relationship harmony (e.g., family harmony and other interpersonal harmony) can be maintained or enhanced. Thus, although filial ethics mainly applies to parent–child relationships, its influence extends to other types of hierarchical social relationship.

Although filial ethics is commonly emphasized in Confucianism, it has been demonstrated to be an etic construct (e.g., Chen, Bond, & Tang, 2007; Ho, 1994; Sommers, 1986). Relational norms between parents and children, such as gratitude towards and care for one’s parents, were observed among Hispanic Americans, and in Taiwan, Thailand, South Korea, and Japan (Hosoe, Takeda, Sodei, Cheng, & Sue, 1991; Kao & Travis, 2005; Maehara & Takemura, 2007; Sung, 1998; Yeh & Bedford, 2003). In the United States, European American, Asian American, and Latino children showed similar levels of family assistance and respect for parents (Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999). In the United States and South Korea, children who cared for their parents offered reasons consistent with filial ethics (e.g., showing affection for parents and fulfilling filial responsibility; Sung, 1997).

FILIAL PRACTICES IN THE UNITED STATES AND TAIWAN

Despite major social changes in Taiwan over the past few decades that have challenged fundamental values and norms (e.g., Lu & Yang, 2006), filial ethics remains strong a relationship norm in Taiwan (e.g., Yeh, 1997). This is especially true for certain aspects of filial ethics that do not presume parents to have absolute power (Yeh, 1997; Yeh & Bedford, 2003). That is, some aspects of filial ethics may define individuals’ respect for and submission to parents due to the parents’ authority roles, whereas other aspects may define individuals attending to parents out of gratitude and are guided by social exchange norms. It is plausible that recent social changes in Taiwan and the individualistic culture in the United States promote views of parent–child relationships as communal as opposed to authoritarian.

SOCIAL PERCEPTIONS OF FILIAL PRACTICES

Given universal filial ethics, surprisingly little research has examined how filial practices actually influence trait perception cross-culturally. Individuals may infer trait information about an actor based on his or her filial practices, or behaviour consistent with filial ethics. For example, Miller (1984) found that Hindu and American children’s dispositional inferences differed based on whether they considered actors’ behaviour as deviating from or conforming to relational norms. Moreover, examining social perceptions of filial practices cross-culturally may reveal the implicitly assumed nature of filial relationships.

In this study, we aimed to understand assumptions about filial relationships by examining trait perceptions of filial practices cross-culturally along two important dimensions: powerfulness and trustworthiness. Perceptions of powerfulness and trustworthiness should vary by how one assumes the nature of a relationship. That is, one may evaluate the same behaviour differently depending on one’s assumption of the nature of the relationship in which the behaviour occurs. If parent–child relationships are assumed to be authoritarian, children should be viewed with less power when they exhibit behaviours consistent with filial ethics than when they do not. Conversely, if the parent–child relationship is assumed to be communal (Clark & Mills, 1979), in which children are expected to voluntarily care for and love their parents despite situational factors, children should be viewed as more trustworthy and powerful when they exhibit behaviours consistent with filial ethics that aim to maintain positive parent–child relationship than when they do not. In this case, power is the ability to meet survival needs (see Pratto, Lee, Tan, & Pitpitan, 2010), contrary to the common definition of power as domination over others (e.g., McClelland, 1979).

HYPOTHESES

We examined participants’ trait perceptions of the actors’ behaviours, without referring to “filial ethics” to avoid invoking different conceptualizations of this specific term in the two cultural contexts. We assumed that the nature of filial relationships has implications for perceptions of actors’ dispositional traits based on their behaviours, and we conceptualized filial relationships as authoritarian or communal. Specifically, we examined perceptions of actors’ general disposition on powerfulness. In addition to perceptions of power traits that may help reveal participants’ assumed nature of filial relationships, we examined perceptions of trustworthiness because, as a measure of one’s reliability within relationships, trustworthiness reflects an important relational trait. Finally, we also examined the perceived quality of the parent–child relationship.

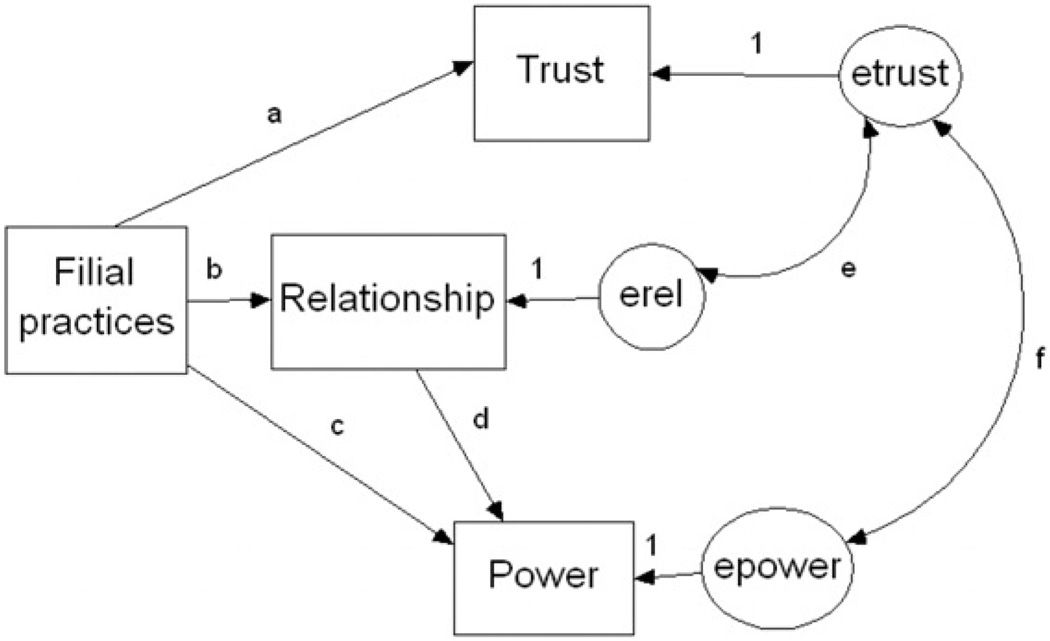

We derived a path model in order to test the following hypotheses (see Figure 1). Because filial ethics govern a fundamental relationship among parents and children, perceivers should attribute more trust-traits to actors who behave consistently with filial ethics than those who do not (path a). By the same token, perceivers should consider actors to have better relationships with parents when they behave according to filial ethics than when they do not (path b). There are two implications of filial practices on perception of actors’ power-traits. If perceivers presume the nature of parent–child relationships to be authoritarian, actors who behave according to filial ethics, which means that they obey the prescribed ethics, should be viewed as less powerful than actors who behave inconsistently with filial ethics (path c). However, if perceivers presume the nature of parent–child relationships to be communal, actors who behave according to filial ethics should be viewed as more powerful because they have the ability to meet their needs in having a positive relationship with parents. The relation between filial practices and perceptions of power-traits should be mediated by the perceived quality of the relationship with one’s parents (path d). That is, when the actor is perceived as choosing to fulfill filial responsibilities to maintain good relationships with parents, the actor should be perceived as being more powerful. In this case, power is the ability to act voluntarily in order to meet one’s relational needs (Pratto et al., 2010). Indirect evidence supports our reasoning: Members in both individualistic cultures (e.g., European Americans) and collectivistic cultures (e.g., Hindu Indians) were found to report the same level of satisfaction from their filial practices, or behaviours that fulfilled filial duties and obligations (Miller, 1997). This finding suggests that agency (as well as other power-traits) may be experienced through filial practices in both cultures. Because traits and relationship quality involve the same actor, covariances were proposed between the two types of traits and relationship quality (covariances e and f).

Figure 1.

Perceived powerfulness, trustworthiness, and quality of relationship between parents and children for the actors.

We further examined whether the models were equivalent in the two cultural samples by constraining the paths, covariances, and variances to be the same. If the models were not equivalent, this strategy would obtain poor model fit indices. On one hand, models may be equivalent for both Americans and Taiwanese because filial ethics are fundamental in the respective cultures. On the other hand, models may not be equivalent between the samples because behaviours may be viewed uniquely due to an elaborate knowledge of filial ethics in Taiwan, so the implications of behaviour for social perceptions may be stronger in Taiwan than in the United States. Moreover, the prototypical parent–child relationship, as indicated by fulfilling filial ethics, may reflect power differentials as in ancient Chinese culture (see Fiske, 1992, p. 701), but as communal in the United States. Thus, some Taiwanese may view actors who behave according to filial ethics as more trustworthy but less powerful. Alternatively, the same actors may be viewed as more trust-worthy and more powerful by both Americans and other Taiwanese because the actors are able to meet their relationship needs.

METHOD

Participants

We recruited participants from electronic bulletin boards in Taiwan and a website (psychsurvey.org) in the United States. These were used commonly by college students and young people. In Taiwan, there were 74 participants (44 women); most were undergraduate students (73.7%), most were of Minnan ethnicity (66.2%), and they averaged 23 years of age. There were 112 American participants (74 women); most had received at least some college education (71.5%), most were Caucasian (78.6%), and they averaged 19 years of age.

Procedure

The experiment was a 2 (Culture: United States and Taiwan) × 2 (Filial behaviour: following filial ethics or not) between-subject design. All participants were randomly assigned to one of two versions featuring same-sex actors (e.g., female participants rated female actors). In each version, all actors either behaved according to filial ethics or not. Relative to a within-subjects design, the between-subject design allows for a conservative test of the effect of filial behaviour because the participants evaluate the targets according to their implicit relationship model, rather than contrasting different filial behaviours (follow or not). Each version contained six scenarios developed from filial ethics items in Yeh (1997), including “regardless of how your parents treat you, you should treat them nicely;” “Fulfill parents’ wishes and give up your career plans;” “Support your parents so that they can live comfortably;” “Be grateful to parents for raising you;” “Save your parents’ face by defending them from gossip;” “Bring honor and prestige to your family.” Targets in the follow-filial-ethics condition exhibit behaviours as described in the items. In the other version, reasons were offered in each scenario to justify individuals’ inconsistent behaviours with the teaching of filial ethics (e.g., due to work, parents’ partial treatment, ability). The term “filial ethics” did not appear in any of the scenarios. Each version of the scenarios was translated and back-translated by the authors, and scenarios were worded to be culturally appropriate. For example:

[Followed filial ethics] Cathy feels that her parents favoured her other siblings ever since she was little. Although she felt that her parents did not love her as much, she never holds grudges against her parents. She cares about her parents and is sensitive to their needs.

[Did not follow filial ethics] Cathy feels that her parents favoured her other siblings ever since she was little, and did not love her as much. As she grew older, she and her parents drifted further and further apart. She has little concern about her parents’ life.

Measures

Participants rated actors on adjectives of power and trustworthiness by indicating the strength to which they felt the target had each particular trait from 0 (no feeling) to 4 (precisely how I feel). Using the same scaling, participants also responded to a single item as to whether the actor had a good relationship with parents. The ways in which these words are commonly used in Chinese are roughly the same as in English: Power refers commonly to “power-over” agency, and independence, and trustworthiness is a relational quality in a person indicating the extent to which one is reliable and dependable. Measures had good reliability (α values > .79, see Table 1 for the items). The reliabilities of general power, general trustworthiness, and parent–child relationships across scenarios were adequate (α values > .65). To account for potentially different response sets between the Taiwanese and American samples, all responses were group-centered by their respective grand culture means. Path analysis was conducted using AMOS 6.0.

TABLE 1.

Reliabilities of the measures across scenarios

| Target characteristics | α | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Items | Taiwan | United States |

| Relationship | Relationship with parents (single item) | – | – |

| Across six scenarios | .79b | .82b | |

| Powerfulness | Influential and powerful | .85a | .79a |

| Across six scenarios | .65b | .77b | |

| Trustworthiness | Moral, trustworthy, untrustworthy (R), valued, and praised | .87a | .85a |

| Across six scenarios | .85b | .79b | |

For each of the three constructs, reliabilities were derived afirst in each scenario, and then bacross the six scenarios.

RESULTS

We provide an overview of the included variables before we examine the theoretical model for perceptions of trustworthiness, powerfulness, and the perceived quality of parent–child relationship. Because there were no participant gender main effect or interaction effects (p values > .28), participant gender was not further explored.

Actors who behaved according to filial ethics were perceived by both Taiwanese and American samples to have a better relationship with parents, F(1, 182) = 271.81, p < .001, as well as to be more trustworthy, F(1, 182) = 414.00, p < .001, than actors who did not (see Table 2). Consistent with our conceptualization of power in communal parent–child relationships, actors who behaved according to filial ethics were rated by both Taiwanese and American samples as more powerful, F(1, 182) = 12.90, p < .001. Furthermore, we observed a significant culture by filial behaviour interaction effect on trustworthiness, F(1, 182) = 9.41, p =.002. Post hoc tests showed that, compared to the Americans, the Taiwanese evaluated actors as more trustworthy when actors behaved consistently with filial ethics, and as less trustworthy when they behaved inconsistently with filial ethics (see the second row from the bottom of Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Relationship quality, power- and trust-perceptions of targets: Means and standard deviations

| Cultural samples | Taiwan | United States | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With filial ethics | Inconsistent | Consistent | Inconsistent | Consistent |

| Sample size | 38 | 36 | 51 | 61 |

| Good relationship1 | −0.72 (0.53) | 0.73 (0.57) | −0.68 (0.55) | 0.69 (0.61) |

| Trust1,2 | −0.63 (0.31)d | 0.64 (0.44)a | −0.46 (0.26)c | 0.48 (0.41)b |

| Power1 | −0.12 (0.58) | 0.16 (0.77) | −0.23 (0.47) | 0.26 (0.90) |

Standard deviations given in parentheses.

1: Filial behaviour main effect;

2: Cultural × Filial behaviour interaction effect.

Superscripts of different letters indicate significant differences at post hoc tests.

Specifically, because we viewed power not as domination in relationships but as ability to meet needs, we expected that the more positively parent–child relationship quality was rated, the more actors would be perceived with power-traits. Conversely, if participants viewed parent–child relationships as authoritarian, they might rate actors who follow filial ethics lower on power-traits. Overall, the theoretical model explains the data well, χ2df=8,N=186=6.54, p = .59, with good fitting indices (CFI =1.00, RMSEA =.000).

We found the models to be largely equivalent in the two cultural samples except for the relation between filial behaviour and perception of trust-traits. The Taiwanese were more affected by actors’ filial practices when they evaluated trust-traits than were the Americans, Δχ2df=1 = 19.46, p < .001. Other paths, covariances, and variances were equivalent in the two cultural samples (see Table 3). When actors behaved according to filial ethics, they were perceived to have a better relationship with parents (b values = 1.40; see Table 3) and to be more trustworthy (b values = 1.29 for Taiwanese and 0.93 for Americans) than actors who behaved inconsistently with filial ethics. Interestingly, when controlling for the quality of filial relationships, filial practices were associated directly with perceptions of lower power as suggested by viewing actors in authoritarian filial relationships (b values = 0.41 for both cultural samples), but the actors’ positive filial relationships were associated with more power-trait perception (b values = 0.58 for both cultural samples), consistent with our conceptualization of power as ability to meet needs in communal parent–child relationships. The mediation effect of filial practices on perceptions of power-traits through perceived quality of parent–child relationship was significant (ZSobel = 6.52, p < .001). Moreover, the indirect effect of filial practices on perception of power-traits through perceived quality of parent–child relationship (standardized indirect effect = .82 in both Taiwan and the United States) seemed to be more important than the direct effect of filial practices on perceptions of power-traits (standardized direct effect = −.28 in both cultures). The findings suggest that in both Taiwan and United States, the prototypical nature of parent–child relationships is communal. Thus, the actors may have been perceived to choose to behave consistently with filial ethics and maintain or enhance a positive relationship with their parents, and this signifies the actors’ power.

TABLE 3.

Unstandardized paths for perceptions of trustworthiness, powerfulness, and perceived quality of parent–child relationship

| Taiwan | United States | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | Path | SE | Path | SE |

| Filial behaviour → Trustworthiness | 1.29*** | .07 | 0.93*** | .06 |

| Filial behaviour → Powera | −0.41** | .15 | −0.41** | .15 |

| Filial behaviour → Relationshipa | 1.40*** | .08 | 1.40*** | .08 |

| Relationship → Powera | 0.58*** | .08 | 0.58*** | .08 |

| Trustworthiness ↔ Relationshipa | 0.12*** | .02 | 0.12*** | .02 |

| Trustworthiness ↔ Powera | 0.08*** | .02 | 0.08*** | .02 |

The paths, covariances, and variances were constrained to be the same across the two cultural samples.

p < .01;

p < .001.

DISCUSSION

What would you do if your parents wished you to choose a career that did not interest you, or would like you to visit them as often as possible although your work responsibilities did not allow you the luxury, or when your parents expected high achievements but you were simply ordinary? Our research offers implications for such dilemmas. Based on the perceptions of power- and trust-traits derived from filial behaviour in two cultural contexts, we found some cultural similarities to suggest that individuals may try very hard to follow filial ethics, because actors who followed them were rated as more trustworthy than those who defied them. Cross-culturally, actors who followed filial ethics were rated as having better relationships with parents, and so they were rated as more powerful than actors who had poorer relationships with parents. Our results imply that cross-culturally, individuals not only share an implicit knowledge of relationship norms (e.g., filial ethics) so that we may be compelled to follow them, but that we also understand the implications of not following these norms. Moreover, the finding that these trait judgments were similar among both Americans and Taiwanese supports the universality of filial ethics in parent–child relationships.

The above findings are largely consistent with viewing parent–child relationships as communal, in which intimacy and communion are emphasized. We also found some weak evidence for emphasizing power differentials in parent–child relationships. After controlling for relationship quality, when actors followed filial ethics, they were rated as less powerful than when actors defied filial ethics, suggesting that given the same relationship quality, participants from both cultural settings perceived actors’ behaviours to signify their lower power relative to their parents. Another way to interpret the results is to use Fiske’s (1992) relational models theory, in which relationships are viewed in distinctive categories. According to Fiske (1992), all human relations may be organized around and understood as one or more of four relational models. Our findings indicate that the nature of parent–child relationships is consistent with two of Fiske’s relational models, communal sharing and authority ranking. In communal sharing, relationships are construed as equivalent and material wealth as communal. In authority ranking, relationships are ordered and hierarchical. Individuals’ assumptions about parent–child relationships may reflect a combination of communal sharing and authority ranking across both cultural settings. Fiske’s other two relational models may be more suitable in explaining exchange relationships (Clark & Mills, 1979): Equality matching, in which relationships are understood in terms of in-kind, tit-for-tat reciprocity; and market pricing model, in which relationships are socially valued in proportion to a common utility metric. Our results are also consistent with a new conceptualization of power offered by Pratto and her colleagues (2010), in that power is defined in relation to one’s needs. Individuals who fulfill their needs (e.g., by maintaining a good parent–child relationship) are perceived to be powerful.

Some cultural differences were also observed. Perhaps because Chinese culture emphasizes filial ethics to a greater degree than American culture, we observed that Taiwanese participants’ perceptions of trustworthiness were influenced by the actors’ behaviours to a larger degree than the Americans. Consistent with findings that certain filial ethics remain important despite major social changes in Taiwanese society (e.g., Yeh, 1997), our findings suggest that following filial ethics greatly reflects a person’s morality (i.e., trustworthiness). Ironically, such an association between parent–child relationships and morality may put burdens on children who cannot fulfill filial ethics due to their abilities (e.g., not able to honor one’s family by high achievements), circumstances (e.g., not able to visit parents frequently due to hectic work), or interests (e.g., not able to be a doctor as parents wish because one is interested in arts). The constraints of filial ethics may be stronger among the Taiwanese because of the stronger association between filial practices and morality (as indexed by trustworthiness) and because of the greater emphasis on relationships among the collectivistic Taiwanese than the Americans.

The current study provided an in-depth look at the underpinnings of relational norms, and suggested that filial behaviour powerfully influenced how one is socially evaluated. Several inferences can be drawn from the study results. First, filial practices appear to have a performative function: Given culture-specific relational norms, people may derive traits and relational meaning from targets’ filial behaviours. The fact that actors who practice filial ethics were judged more favourably implies that children from each culture may implicitly understand practice filialness under such expectations, consistent with previous research that examined the relation between filial attitudes and behaviour (e.g., Chen et al., 2007). Although effects seemed stronger among the Taiwanese, our results demonstrated a cross-cultural sensibility to filialness such that filial practices garnered favourable evaluations from individuals across cultural settings. Future research that examines filial relations may provide important inroads toward understanding social relationships and social perceptions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

REFERENCES

- Chen SX, Bond MH, Tang D. Decomposing filial piety into filial attitudes and filial enactments. Asian Journal of Social Psychology. 2007;10:213–223. [Google Scholar]

- Clark MS, Mills J. Interpersonal attraction in exchange and communal relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1979;37:12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske AP. The four elementary forms of sociality: Framework for a unified theory of social relations. Psychological Review. 1992;99:689–723. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.99.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske AP. Structures of social life: The four elementary forms of human relations. New York, NY: Free Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Tseng V, Lam M. Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Development. 1999;70:1030–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DT, Malone PS. The correspondence bias. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:21–38. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho DY. Filial piety, authoritarian moralism and cognitive conservatism in Chinese societies. Genetic, Social & General Psychology Monographs. 1994;120:349–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoe Y, Takeda K, Sodei T, Cheng S, Sue PS. The attitude and the sense of responsibility of university students toward the aged: Cross cultural study in Japan, Taiwan, and Korea (II) Journal of Home Economics of Japan. 1991;42:305–312. [Google Scholar]

- Kao H-F, Travis SS. Effects of acculturation and social exchange on the expectations of filial piety among Hispanic/Latino parents of adult children. Nursing and Health Sciences. 2005;7:226–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2005.00241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Yang K-S. Emergence and composition of the traditional–modern bicultural self of people in contemporary Taiwanese societies. Asian Journal of Social Psychology. 2006;9:167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Maehara T, Takemura A. The norms of filial piety and grandmother roles as perceived by grandmothers and their grandchildren in Japan and South Korea. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2007;31:585–593. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland DC. Inhibited power motivation and high blood pressure in men. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1979;88:182–190. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.88.2.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JG. Culture and the development of everyday social explanation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46:961–978. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.5.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JG. Agency and context in cultural psychology: Implications for moral theory. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 1997;76:69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ong LML, De Haes JCJM, Hoos AM, Lammes FB. Doctor–patient communication: A review of the literature. Social Science & Medicine. 1995;40:903–918. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00155-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratto F, Lee IC, Tan J, Pitpitan E. Power basis theory: A psycho-ecological approach to power. In: Dunning D, editor. Social motivation. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2010. pp. 191–222. [Google Scholar]

- Ross L. The intuitive psychologist and his shortcomings: Distortions in the attribution process. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 1977;10:174–220. [Google Scholar]

- Ross L, Nisbett RE. The person and the situation: Perspectives of social psychology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Schüler J, Sheldon KM, Fröhlich SM. Implicit need for achievement moderates the relationship between competence need satisfaction and subsequent motivation. Journal of Research in Personality. 2009;44:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sommers CH. Filial morality. Journal of Philosophy. 1986;83(8):439–456. [Google Scholar]

- Sommers SR, Ellsworth PC. Race in the courtroom: Perceptions of guilt and dispositional attributions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26:1367–1379. [Google Scholar]

- Sung K-T. Filial piety in modern times: Timely adaption and practice patterns. Australiasian Journal of Ageing. 1997;17:88–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sung K-T. An exploration of actions of filial piety. Journal of Aging Studies. 1998;12:369–386. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh KH. Changes in the Taiwan people’s concept of filial piety [in Chinese] In: Cheng LY, Lu YH, Wang FC, editors. Taiwanese society in the 1990s. Taipei, Taiwan: Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica; 1997. pp. 171–214. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh K-H, Bedford O. A test of the dual filial piety model. Asian Journal of Social Psychology. 2003;6:215–228. [Google Scholar]