Abstract

Background

High levels of homocysteine have been associated with increased risk for dementia although results have been inconsistent. There are no reported studies from the developing world including Africa.

Methods

In this longitudinal study of two community-dwelling cohorts of elderly Yoruba and African Americans, levels of homocysteine, vitamin B12 and folate were measured from blood samples taken in 2001. These levels were compared in two groups, participants who developed incident dementia in the follow-up until 2009 (59 Yoruba and 101 African Americans) and participants who were diagnosed as cognitively normal or in the good performance category at their last follow-up (760 Yoruba and 811 African Americans). Homocysteine levels were divided into quartiles for each site.

Results

After adjusting for age, education, possession of ApoE, smoking, and time of enrollment the higher quartiles of homocysteine were associated with a non-significant increase in dementia risk in the Yoruba (homocysteine quartile 4 vs. 1 OR: 2.19, 95% CI 0.95-5.07, p = 0.066). For the African Americans, there was a similar but non-significant relationship between higher homocysteine levels and dementia risk. There were no significant relationships between levels of vitamin B12 and folate and incident dementia in either site although folate levels were lower and vitamin B12 levers were higher in the Yoruba than in the African Americans.

Conclusions

Increased homocysteine levels were associated with a similar but non-significant increase in dementia risk for both Yoruba and African Americans despite significant differences in folate levels between the two sites.

Keywords: dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, homocysteine, African Americans, Yoruba

Introduction

Dementia represents a public health problem throughout the world, one that is only likely to increase over time (Ferri et al., 2005). The identification of a modifiable risk factor would represent a major advance in the prevention of dementia but so far no single risk factor has been clearly discovered (Plassman et al., 2010). The amino acid homocysteine is an intriguing candidate. High levels of homocysteine have been associated with increased risk both for cardiovascular disease and for all-cause mortality (Hackam and Anand, 2003; Bates et al., 2010). Evidence of an association of levels of homocysteine with an increased risk for dementia or cognitive decline however has been inconclusive (Seshadri et al., 2002; Luchsinger et al., 2004; Haan et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2008; Kivipelto et al., 2009; Ho et al., 2011). Nevertheless, one recent meta-analysis suggests that cohort studies do indeed show a consistent positive association with high levels of homocysteine and dementia risk (Wald et al., 2011). Most studies so far have been conducted in cohorts from North America and Europe. There is one study from South Korea (Kim et al., 2008). There are no reported studies from the developing world including Africa. Homocysteine homeostasis is influenced by a complex interplay of environmental and genetic factors. Studies on the effects of homocysteine on dementia in African countries would therefore be very informative as dietary patterns are very different from developed countries and genetic diversity is greatest (Hendrie et al., 2004). Our Indianapolis-Ibadan project gave us the opportunity to study the relationship of homocysteine levels and dementia in Nigerians.

The Indianapolis-Ibadan dementia project is a longitudinal comparative study of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in two elderly communities: African Americans living in Indianapolis, and Yoruba living in Ibadan, Nigeria. In 2001, cardiovascular biomarker measurements were added to the study including levels of homocysteine, folate, and vitamin B12. In this paper, we analyze the association between baseline measurements of these biomarkers and incident dementia and AD for the two cohorts.

Methods

Study participants

Since 1992, we have been conducting a comparative, community-based epidemiologic study of prevalence, incidence, and risk factors for AD in populations of African origin: elderly African Americans in Indianapolis, Indiana, and Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria. A detailed description of the construction of the original cohorts has been previously reported (Hendrie et al., 2001). In 2001, we conducted a two-stage study in which survivors of the 1992 cohort were interviewed and new participants were enrolled. In 2001, there were 750 of the original cohort still participating in Indianapolis and 899 in Ibadan. The enrollment of the new study participants in Indianapolis in 2001 used a list of African American Medicare participants, age 70 years, living in Marion County, Indiana. An additional 1,893 were enrolled. In Ibadan, a new community survey conducted in the original research area provided an additional 1,939 participants. The surviving 1992 cohorts and the newly recruited 2001 cohorts were similar in basic demographics, age, and gender. The institutional review boards of Indiana University School of Medicine and University of Ibadan approved the study.

Blood samples

In 2001, blood samples were drawn from participants who consented. The blood samples were drawn in 10-mL EDTA Vacutainer tubes. The specimens were transported on ice from the field to the laboratory at Ibadan University College Hospital. In the laboratory, erythrocytes, buffy coat, and plasma were separated. After labeling, the plasma and buffy coat tubes with a unique bar code for each participant, the samples were stored in a −70 °C freezer. Samples were shipped to Indiana University in approved blood shipping containers with dry ice and arrived usually within three days. Samples from Indianapolis were directly processed at Indiana University. Biochemical analyses were carried out on the plasma. Levels of homocysteine, folate, vitamin B12, were determined by using commercial kits from BioRad, Hercules, CA, and Diasorin, Stillwater, MN. A total of 1,510 blood samples were obtained from African Americans and 1,254 from Yoruba. All the Yoruba blood samples were fasting. Approximately one third, or 503 samples, from African Americans were fasting. All were taken in the morning.

Study design

The Indianapolis-Ibadan Dementia Project is a prospective community-based study with a baseline evaluation followed by regular evaluations scheduled two to three years apart. For participants included in this analysis, the 2001 evaluation constitutes as their baseline, with three follow-up evaluations conducted at 2004, 2007, and 2009.

A two-stage design was used at each evaluation with in-home cognitive and functional evaluations for all participants followed by a full diagnostic workup of selected participants based on the performance of stage one cognitive tests. After each stage one evaluation, study participants were divided into three performance groups (good, intermediate, and poor) based on their cognitive and functional scores obtained during the in-home assessment and changes in scores from previous evaluations (Hendrie et al., 2001). Percentages sampled from each performance category were chosen to ensure that participants with the highest probability of dementia would be clinically assessed. All participants in the poor performance group were invited to be clinically assessed. Participants were randomly sampled from the intermediate performance group until 50% had clinical assessments and from the good performance group until 5% had clinical assessments.

Each clinically assessed participant received a diagnosis of “normal”, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), or dementia, with further subtypes for those diagnosed with dementia (see section on Clinical Evaluation below). All individuals diagnosed as people with dementia reached their endpoint in the study and were no longer followed. Participants who were diagnosed with MCI in a previous wave proceeded directly to the clinical assessment stage regardless of their first stage scores.

Cognitive instruments

The Community Screening Interview for Dementia (CSID) was used during the first stage in-home assessment with a cognitive assessment of the study participant and an interview with a close relative evaluating the daily functioning of the participant. The CSID was developed by our group specifically for use in comparative epidemiological studies of dementia in culturally disparate populations (Hall et al., 2000). The cognitive assessment in CSID evaluates multiple cognitive domains (language, attention and calculation, memory, orientation, praxis, and comprehension and motor response) (Ravaglia et al., 2008).

Clinical evaluation

Clinical evaluations included (1) a neuropsychological battery adapted from the Consortium to Establish a Registry of Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD)(Morris et al., 1989); (2) a standardized neurologic and physical exam, and functional status review (The Clinician Home-based Interview to assess Function CHIF) (Hendrie et al., 2006); and (3) a structured interview with a close relative adapted from the Cambridge Examination for Mental Disorders of the Elderly informant interview (CAMDEX) (Hendrie et al., 1988). Following the second stage of evaluation, participants were diagnosed as having normal cognitive function, dementia, or MCI. Diagnosis was made in a consensus diagnostic conference of clinicians reviewing the CERAD neuropsychological test battery, the physician’s assessment, the informant interview, and available medical records. Dementia was diagnosed with both the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised Third Edition (DSM-III-R) (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) and International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) (American Pychiatric Association Press, 1992) criteria. AD was diagnosed using criteria proposed by NINCDS/ADRDA (McKhann et al., 1984). Criteria for MCI were as follows: informant-reported decline in cognition, clinician’s detected impairment in cognition during the assessment, or cognitive test scores 1.5 standard deviation below the mean of the normative reference sample and normal instrumental and basic activities of daily living (based on the informant interview) (Unverzagt et al., 2001; Baiyewu et al., 2002; Unverzagt et al., 2011).

Other information

Demographic information including age, sex, and education (years of education for African Americans, whether or not they attended school for Yoruba) were available on all study participants. Information was also collected on alcohol and smoking history on whether the participant ever consumed alcohol or smoked regularly. In addition, medical conditions that may affect cognitive function were collected at each of the evaluation times. In particular, medical history of coronary heart disease, cancer, diabetes, heart attack, hypertension, Parkinson’s disease, stroke, and depression were collected from self or informant reports as affirmative answers to whether the participants had ever been diagnosed or treated for these diseases.

Analysis

The primary study outcome was incident dementia, defined as a diagnosis of dementia as determined by the comprehensive clinical assessment during follow-up. Those who were diagnosed with normal cognition or were in the good performance group on screening at their final participating wave were considered to be cognitively unimpaired. Participants diagnosed with dementia in 2001 were not included. Homocysteine was split into quartiles separately for each site. t tests and χ2 tests (or Fisher’s exact tests for small sample sizes) were used to compare continuous and categorical variables between those with incident dementia and the cognitively normal. Univariate logistic regression was used to identify variables significantly associated with incident dementia at the α = 0.15 level within each site. These were included in multivariable models where forward and backwards selection modeling techniques were employed to identify a final parsimonious model with homocysteine quartiles as the independent variable and adjusting for covariates significant at the α = 0.05 level. Interactions between homocysteine and ApoE E4 allele status were investigated but not included unless significant. This analysis was also repeated for those with incident AD and the cognitively normal. Odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and p values are reported from the final models.

Results

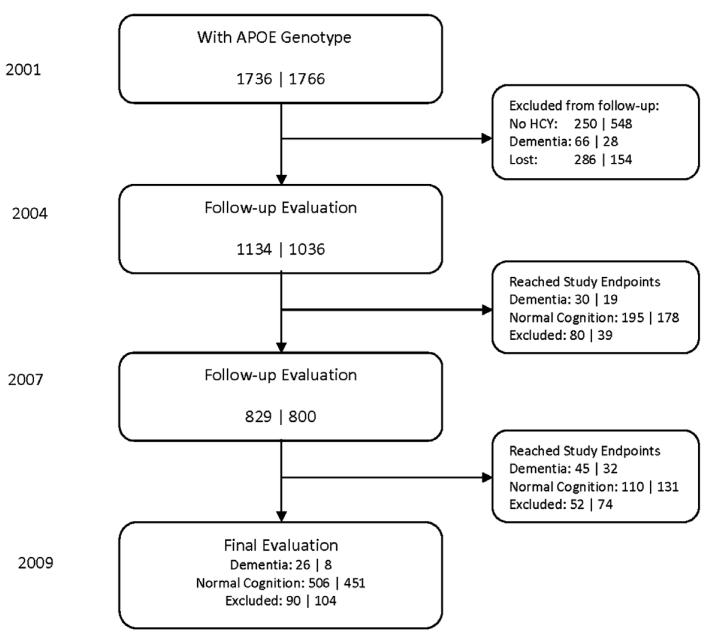

A flow chart describing the process for selecting the participants who had homocysteine measurements, were APOE genotyped, and were classified as either having incident dementia or normal cognition during follow up is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the number of study participants evaluated during follow-up. Each of the number pairs denotes the numbers of African Americans and Yoruba, respectively. The total numbers of participants with incident dementia come from the 2004, 2007, and 2009 evaluations and the total numbers of participants with normal cognition consist of those from the 2009 evaluation and those who reached their endpoints at the 2004 or 2007 evaluation.

In the African American cohort, incident dementia was diagnosed in 101 participants and 811 participants were identified as having normal cognition.

In the Yoruba cohort, incident dementia was diagnosed in 59 participants and 760 were identified as having normal cognition.

Table 1 compares the baseline characteristics of the participants with incident dementia with the participants with normal cognition in both sites. For the African American cohort, the participants with incident dementia were significantly older, less educated than the participants without dementia, and significantly more likely to possess the ApoE E4 allele (p < 0.001 for age, p < 0.001 for education, p < 0.001 for ApoE E4). They were also significantly less likely to have a smoking history (p = 0.002). There was a higher rate of incident dementia in those enrolled in 1992 than for participants enrolled in the 2001 wave (p < 0.001). There were no significant differences in levels of homocysteine, vitamin B12 or folate. Approximately two thirds of the African American samples were non-fasting. However, there were no differences in levels of homocysteine, B12, and folate between the fasting and non-fasting samples. In the Yoruba cohort, the participants who developed incident dementia were significantly older and less educated than the participants without dementia (p < 0.001 for age, p < 0.050 for education). They had significantly higher average homocysteine levels and were significantly more likely to have a history of smoking (homocysteine, p = 0.044; smoking, p = 0.002). There was also a significantly higher rate of incident dementia in those enrolled in 1992 than in those enrolled in 2001 (p = 0.018). There were no significant differences in levels of vitamin B12 or folate. There were no other significant differences in comorbidity history for either site.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of African American and Yoruba participants with incident dementia and normal cognition.

| AFRICAN AMERICANS |

YORUBA |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NORMAL COGNITION (n = 811) |

INCIDENT DEMENTIA (n = 101) |

p VALUE | NORMAL COGNITION (n = 760) |

INCIDENT DEMENTIA (n = 59) |

p VALUE | |

| Age, mean ± SD | 76.39 ± 4.81 | 79.67 ± 6.13 | <0.0001 | 75.56 ± 4.49 | 80.06 ± 7.21 | < 0.0001 |

| Male, n (%) | 245 (30.21%) | 25 (24.75%) | 0.2573 | 277 (36.45%) | 17 (28.81%) | 0.2390 |

| Years of education (African American), mean ± SD/attended school (Yoruba), n (%) |

11.59 ± 2.38 | 10.43 ± 3.18 | 0.0005 | 125 (16.45%) | 4 (6.78%) | 0.0496 |

| Enrolled in 1992, n (%) | 144 (17.8%) | 34 (33.7%) | 0.0001 | 223 (29.3%) | 36 (44.1%) | 0.0178 |

| Body mass index, mean ± SD |

30.08 ± 5.74 | 28.91 ± 5.49 | 0.0538 | 21.87 ± 4.64 | 20.81 ± 4.43 | 0.0928 |

| Has ApoE E4 allele, n (%) | 252 (31.1%) | 50 (49.50%) | 0.0002 | 298 (39.2%) | 28 (47.46%) | 0.2125 |

| Homocysteine (umole/L), mean ± SD |

16.25 ± 6.87 | 16.98 ± 6.40 | 0.3094 | 17.13 ± 6.76 | 19.00 ± 7.88 | 0.0440 |

| Folate (ng/mL), mean ± SD |

11.22 ± 15.68 | 10.38 ± 9.49 | 0.4505 | 5.90 ± 7.87 | 5.37 ± 2.50 | 0.2240 |

| Vitamin B12, mean ± SD | 620.37 ± 359.68 | 673.02 ± 394.89 | 0.1742 | 791.78 ± 317.66 | 783.46 ± 266.19 | 0.8448 |

| Self and/or informant report History of: |

||||||

| Angina, n (%) | 55 (6.86%) | 7 (6.93%) | 0.9782 | 31 (4.08%) | 3 (5.08%) | 0.7297 |

| Anxiety, n (%) | 83 (10.32%) | 14 (14.14%) | 0.2470 | 10 (1.32%) | 1 (1.69%) | 0.5629 |

| Arthritis, n (%) | 553 (69.82%) | 66 (67.35%) | 0.6153 | 178 (23.45%) | 14 (23.73%) | 0.9614 |

| Cancer, n (%) | 134 (16.77%) | 12 (12.12%) | 0.2369 | 9 (1.19%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1.0000 |

| Depression, n (%) | 71 (8.83%) | 10 (10.10%) | 0.6764 | 83 (10.92%) | 8 (13.56%) | 0.5345 |

| Have a relative with memory problems, n (%) |

105 (13.16%) | 17 (17.00%) | 0.2905 | 19 (2.53%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0.3888 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 231 (28.73%) | 29 (28.71%) | 0.9969 | 13 (1.71%) | 1 (1.72%) | 1.0000 |

| Epilepsy, n (%) | 11 (1.36%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0.6217 | 1 (0.13%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1.0000 |

| Head injury, n (%) | 74 (9.20%) | 5 (5.00%) | 0.1604 | 28 (3.68%) | 5 (8.47%) | 0.0813 |

| Heart attack, n (%) | 94 (11.66%) | 9 (9.00%) | 0.4289 | 27 (3.55%) | 3 (5.08%) | 0.4706 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 628 (78.50%) | 78 (78.79%) | 0.9475 | 202 (26.65%) | 20 (34.48%) | 0.1963 |

| Kidney disease, n (%) | 37 (4.58%) | 3 (2.97%) | 0.6106 | 1 (0.13%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1.0000 |

| Liver disease, n (%) | 10 (1.24%) | 1 (1.00%) | 1.0000 | 57 (7.50%) | 2 (3.39%) | 0.3050 |

| Lung disease, n (%) | 60 (7.41%) | 3 (2.97%) | 0.0975 | 30 (3.95%) | 2 (3.39%) | 1.0000 |

| Parkinson’s disease, n (%) | 3 (0.37%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1.0000 | 22 (2.89%) | 4 (6.78%) | 0.1102 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 105 (13.00%) | 20 (20.00%) | 0.0551 | 12 (1.58%) | 3 (5.08%) | 0.0867 |

| Thyroid disease, n (%) | 109 (13.52%) | 17 (16.83%) | 0.3649 | 1 (0.13%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1.0000 |

| Alcohol use, n (%) | 290 (39.30%) | 27 (31.40%) | 0.1541 | 315 (41.45%) | 20 (33.90%) | 0.2559 |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 456 (56.51%) | 40 (40.00%) | 0.0018 | 276 (36.32%) | 29 (49.15%) | 0.0494 |

In univariate logistic models on incident dementia, for the African American cohort, the risk for incident dementia was significantly increased with increased baseline age, fewer years of education and possession of the ApoE E4 allele and significantly decreased with a history of smoking (p < 0.001). Quartiles of homocysteine, vitamin B12, and folate did not significantly affect the risk of dementia although there was a trend for the risk of dementia to increase in the higher quartiles of homocysteine and decrease in the higher quartiles of folate. BMI levels and having a history of stroke were marginally associated with incident dementia (BMI p = 0.054, stroke: p = 0.057). For the Yoruba cohort, the risk for dementia was significantly increased with baseline age (p < 0.001) and the higher quartiles of homocysteine (p < 0.034). History of head injury, stroke, and smoking were marginally associated with incident dementia (head injury p = 0.080; stroke p = 0.068; smoking p = 0.052). There was no significant association of increased risk of dementia with levels of folate and vitamin B12.

Table 2 shows the results from the final logistic regression model on incident dementia for both sites. In African Americans, homocysteine was not significantly associated with incident dementia (p = 0.304) after adjusting for years of education, baseline age, presence of an ApoE E4 allele, smoking history, and time of enrollment (1992 vs. 2001). An interaction between homocysteine and ApoE E4 allele status was investigated but found to be non-significant (p = 0.427). In the Yoruba, homocysteine was also not significantly associated with incident dementia (p = 0.245) after adjusting for education, baseline age, and time of enrollment. In both sites, however, there was a non-significant trend for the higher quartiles of homocysteine to be associated with a higher risk for dementia. When incident AD is used as the outcome, the results for homocysteine are similar for both cohorts.

Table 2. Results from final logistic regression models on incident dementia for both cohorts.

| AFRICAN AMERICANS* |

YORUBA |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ODDS RATIO | 95% CI | p VALUE | ODDS | RATIO 95% CI | p VALUE | |

| Homocysteine: | 0.3044 | 0.2451 | ||||

| Q4 versus Q1 | 1.41 | 0.73–2.71 | 0.3094 | 2.19 | 0.95–5.07 | 0.0662 |

| Q3 versus Q1 | 1.78 | 0.94–3.38 | 0.0771 | 1.39 | 0.57–3.38 | 0.4679 |

| Q2 versus Q1 | 1.16 | 0.58–2.28 | 0.6740 | 1.27 | 0.52–3.09 | 0.6012 |

| Years of education (African Americans)/ attended school (Yoruba) |

0.86 | 0.79–0.94 | 0.0004 | 0.30 | 0.10–0.88 | 0.0284 |

| Age | 1.10 | 1.06–1.15 | <0.0001 | 1.12 | 1.07–1.17 | <0.0001 |

| Has ApoE E4 allele | 2.70 | 1.71–4.26 | <0.0001 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| History of Smoking | 0.51 | 0.33–0.81 | 0.0040 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Enrolled in 1992 | 1.84 | 1.13–3.00 | 0.0150 | 1.57 | 0.88–2.78 | 0.1243 |

Two additional analyses were conducted to estimate the possible effects of selection and drop out bias. Participants who did not have homocysteine measurements were significantly older in the Yoruba (p < 0.001), were more likely to be enrolled in 1992 (p < 0.001) for both sites, and had slightly lower cognitive scores at baseline in both sites reaching significance for the Yoruba (p = 0.010).

Participants who were not included in the analysis for lack of follow up (primarily due to death) were older (p < 0.001 for both sites), less likely to be female in the African American cohort (p < 0.001), but less likely to be male in the Yoruba cohort (p = 0.001), had significantly less education in the African American cohort (p < 0.001) but not in the Yoruba cohort, had lower baseline cognitive scores (p < 0.001 for both sites), and were more likely to be enrolled in 1992 (p < 0.001 for the African Americans; p = 0.002 for the Yoruba).

Discussion

In our study, in the elderly Yoruba, the higher quartiles of homocysteine levels were significantly related to an increase in dementia risk in the univariate analyses (p = 0.034). This significance was lost when age and education were introduced into the model although the trend remained positive particularly for the highest quartile of homocysteine levels (see Table 2). For the African Americans, there were no significant relationships between higher homocysteine levels and dementia risk in either models but again the trend was positive for the higher levels of homocysteine. There was no relationship between levels of folate and vitamin B12 and dementia risk for either cohort. When incident AD is used as the outcome the results are similar. In this analysis, a history of smoking was rather surprisingly associated with a reduced risk of dementia for African Americans. Most recent analyses have concluded that smoking is a risk factor for incident dementia (Barnes and Yaffe, 2011). However, our category for smoking also included individuals who had stopped smoking and the average age of our cohort was older than in most other studies.

Previous community-based studies of the association of homocysteine levels with incident dementia have been inconsistent although most indicated a similar positive association, albeit not necessarily reaching significance (Seshadri et al., 2002; Haan et al., 2007; Ravaglia et al., 2008; Kivipelto et al., 2009). In a recent meta-analysis which included the community based studies, Wald et al. (2011) reported a significant positive association between increasing levels of serum homocysteine and incident dementia with an OR of 1.35 (95% CI 1.02-1.79).

It is noteworthy that the results are similar in Yoruba and African Americans where it might be anticipated that differences in diet and environment would have influenced both homocysteine levels and the association to dementia. In our study when comparisons were made between sites, there was no significant difference in homocysteine levels between the Yoruba and African Americans but levels of folate were significantly lower and levels of vitamin B12 were significantly higher in the Yoruba. Both cohorts had relatively higher levels of homocysteine than those reported for the general US population but levels of folate and vitamin B12, although significantly different between cohorts, all fell within the US norms (Deeg et al., 2008). The diet of the elderly Yoruba has been reported to be low in B vitamins including folate (Olayiwola et al., 2012).

The explanation for the higher levels of homocysteine in the two cohorts particularly in view of the very different levels of folate is unclear at this time. It has been suggested that polymorphisms in genes that regulate homocysteine homeostasis, particularly polymorphisms in the folate metabolizing genes, may explain this observation (Devlin et al., 2006; Ozarda et al., 2009).

The similarity in effect size for the association of high levels of homocysteine with dementia risk between the two cohorts despite the significant differences in levels of folate between the two sites does not appear to support the concept that augmentation of folate would reduce the homocysteine-induced risk for dementia. Indeed results from augmentation trials of folate with and without B12 for cognitive outcomes have been disappointing (Dangour et al., 2010).

Limitations

Blood samples were taken only once. It is possible that individual levels of homocysteine could fluctuate over the study period. Approximately two thirds of the African American samples were non-fasting. However, there were no differences in levels of homocysteine, B12, and folate between the fasting and non-fasting samples. There was no dietary information available from either site including information on vitamin supplementation.

Participants who were excluded from the analyses because of lack of homocysteine measurements or lack of follow up primarily due to death tended to be older, with less education and lower cognitive scores. All these factors were included in the final models thus minimizing potential selection bias under the missing at random mechanism. It is possible however, that selection bias occurred from factors not included in the study. It is also possible that excluded participants were more likely to have developed dementia.

Additionally the number of participants with a diagnosis of incident dementia was relatively small particularly in the Yoruba.

In conclusion, in this study a similar pattern was observed in the Yoruba and African American cohorts with increased homocysteine levels being associated with a non-significant increase in dementia risk for both Yoruba and African Americans despite significant differences in folate levels. These results suggest that the relationship between homocysteine and increased dementia risk is worth exploring further. The studies would be greatly enhanced if they included pertinent dietary and genetic information and larger numbers of participants with dementia.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

This research was supported by NIH grant RO1 AG09956 and NIH grant P30 AG10133.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd edn. American Psychiatric Assocation; Washington, DC: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association Press . ICD-10. The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems: 1 and 2. American Psychiatric Association Press; Washington, DC: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Baiyewu O, et al. Cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older Nigerians: clinical correlates and stability of diagnosis. European Journal of Neurology. 2002;9:573–580. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2002.00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes DE, Yaffe K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. Lancet Neurology. 2011;10:819–828. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70072-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates CJ, Mansoor MA, Pentieva KD, Hamer M, Mishra GD. Biochemical risk indices, including plasma homocysteine, that prospectively predict mortality in older British people: the National Diet and Nutrition Survey of people aged 65 years and over. The British Journal of Nutrition. 2010;104:893–899. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510001236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangour AD, et al. B-vitamins and fatty acids in the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia: a systematic review. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2010;22:205–224. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-090940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeg M, et al. A comparison of cardiovascular disease risk factor biomarkers in African Americans and Yoruba Nigerians. Ethnicity & Disease. 2008;18:427–433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin AM, Clarke R, Birks J, Evans JG, Halsted CH. Interactions among polymorphisms in folate-metabolizing genes and serum total homocysteine concentrations in a healthy elderly population. The American Journal of Clinicial Nutrition. 2006;83:708–713. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.83.3.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri CP, et al. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. 2005;366:2112–2117. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67889-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haan MN, et al. Homocysteine, B vitamins, and the incidence of dementia and cognitive impairment: results from the Sacramento Area Latino Study on aging. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007;85:511–517. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.2.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackam DG, Anand SS. Emerging risk factors for atherosclerotic vascular disease: a critical review of the evidence. JAMA. 2003;290:932–940. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.7.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall KS, Gao S, Emsley CL, Ogunniyi AO, Morgan O, Hendrie HC. Community screening interview for dementia (CSI ‘D’); performance in five disparate study sites. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2000;15:521–531. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200006)15:6<521::aid-gps182>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrie HC, et al. The CAMDEX: a standardized instrument for the diagnosis of mental disorder in the elderly: a replication with a US sample. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1988;36:402–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb02378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrie HC, et al. Incidence of dementia and Alzheimer disease in 2 communities: Yoruba residing in Ibadan, Nigeria, and African Americans residing in Indianapolis, Indiana. JAMA. 2001;285:739–747. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.6.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrie HC, Hall KS, Ogunniyi A, Gao S. Alzheimer’s disease, genes, and environment: the value of international studies. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;49:92–99. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrie HC, et al. The development of a semi-structured home interview (CHIF) to directly assess function in cognitively impaired elderly people in two cultures. International Psychogeriatrics. 2006;18:653–666. doi: 10.1017/S104161020500308X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho RC, et al. Is high homocysteine level a risk factor for cognitive decline in elderly? A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2011;19:607–617. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181f17eed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JM, et al. Changes in folate, vitamin B12 and homocysteine associated with incident dementia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 2008;79:864–868. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.131482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivipelto M, et al. Homocysteine and holo-transcobalamin and the risk of dementia and Alzheimers disease: a prospective study. European Journal of Neurology. 2009;16:808–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchsinger JA, Tang MX, Shea S, Miller J, Green R, Mayeux R. Plasma homocysteine levels and risk of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2004;62:1972–1976. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000129504.60409.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1989;39:1159–1165. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.9.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olayiwola IO, Fadupin GT, Agbato SO, Soyewo DO. Serum micronutrient status and nutrient intake of elderly Yoruba people in a slum of Ibadan, Nigeria. Public Health Nutrition. 2012:1–7. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012004971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozarda Y, Sucu DK, Hizli B, Aslan D. Rate of T alleles and TT genotype at MTHFR 677C->T locus or C alleles and CC genotype at MTHFR 1298A->C locus among healthy subjects in Turkey: impact on homocysteine and folic acid status and reference intervals. Cell Biochemistry and Function. 2009;27:568–577. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plassman BL, Williams JW, Jr., Burke JR, Holsinger T, Benjamin S. Systematic review: factors associated with risk for and possible prevention of cognitive decline in later life. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2010;153:182–193. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-3-201008030-00258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravaglia G, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: epidemiology and dementia risk in an elderly Italian population. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56:51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshadri S, et al. Plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346:476–483. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unverzagt FW, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment: data from the Indianapolis Study of Health and Aging. Neurology. 2001;57:1655–1662. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.9.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unverzagt FW, et al. Incidence and risk factors for cognitive impairment no dementia and mild cognitive impairment in African Americans. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2011;25:4–10. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181f1c8b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald DS, Kasturiratne A, Simmonds M. Serum homocysteine and dementia: meta-analysis of eight cohort studies including 8669 participants. Alzheimers & Dementia. 2011;7:412–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.08.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]