Abstract

Our genetic information is tightly packaged into a rather ingenious nucleoprotein complex called chromatin in a manner that enables it to be rapidly accessed during genomic processes. Formation of the nucleosome, which is the fundamental unit of chromatin, occurs via a stepwise process that is reversed to enable the disassembly of nucleosomes. Histone chaperone proteins have prominent roles in facilitating these processes as well as in replacing old histones with new canonical histones or histone variants during the process of histone exchange. Recent structural, biophysical and biochemical studies have begun to shed light on the molecular mechanisms whereby histone chaperones promote chromatin assembly, disassembly and histone exchange to facilitate DNA replication, repair and transcription.

Histone chaperones

The nucleosome hypothesis for chromatin, proposed by Don and Ada Olins and Roger Kornberg in 19741, 2, was a paradigm shift for research into eukaryotic genomic processes. We now know that chromatin comprises a repeated array of nucleosome core particles of approximately 147 bp DNA wound 1.7 times around the outside of a core histone octamer which includes two molecules each of histone proteins H2A, H2B, H3 and H4 (Box 1)3, 4 separated by varying lengths of linker DNA which can be associated with linker histones3, 4. Transitions from these “beads on a string” as the first level of chromatin organization to highly condensed metaphase chromosomes highlight the dynamic nature of the chromatin structure3, 5. A hierarchy of folding allows for the protection and organization of DNA, but also permits rapid access to the DNA sequence during transcription, replication, repair and recombination. Hundreds of proteins regulate these dynamic transitions in the chromatin structure, including histone chaperones, non-histone DNA-binding proteins, ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes and post-translational modification enzymes6, 7. Histone chaperones are proteins that can assemble histones and DNA into the nucleosome structure as well as disassemble intact nucleosomes into its subcomponents8–11. They are negatively charged proteins that can prevent the non-specific aggregation of positively charged histones and negatively charged DNA. Beyond that, histone chaperones play important roles in regulating the intricate steps involved in folding of histones together with DNA to form correctly assembled nucleosomes. This review will focus on the role of histone chaperones in nucleosome assembly and disassembly pathways as well as the molecular mechanisms that drive these processes.

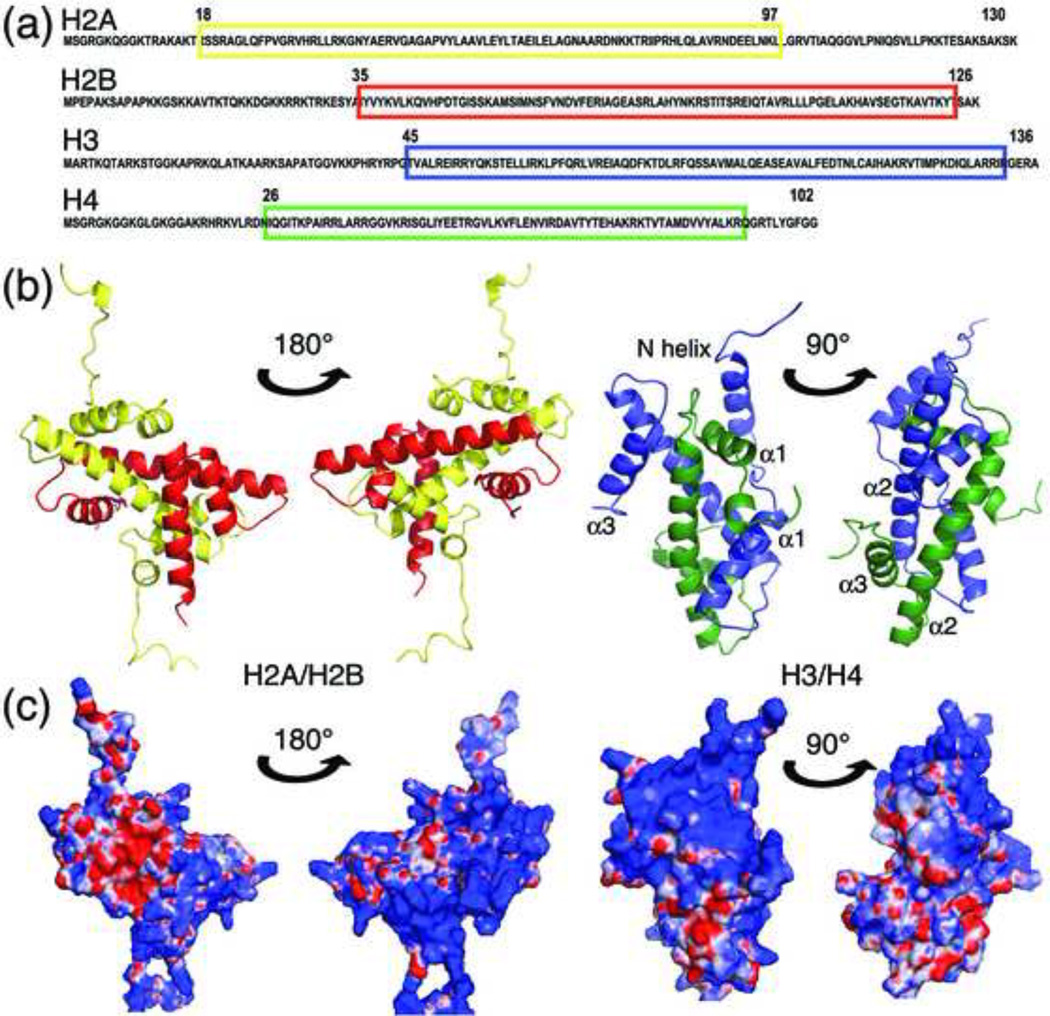

Text Box 1. Chemical nature of the core histone subunits.

The core histones exist in fundamental units of co-folded dimers of either H2A–H2B or H3–H4. Histone proteins fold into a shared three-dimensional structural motif composed of a helix-turn-helix-turn-helix motif, known as the histone fold96. Outside of the core region of each histone that forms the histone fold (boxed in Fig Ia), approximately one third of the remaining polypeptide chains are in an intrinsically disordered state, which usually protrudes from the surface of the assembled nucleosome. The histone fold is primarily a dimerization handshake motif (Fig Ib), where the variations in the edges of the histone dimers lead to the formation of the octameric structure97. The histone fold motif also forms the framework for the wrapping of the DNA around the histone octamer, which is mediated via non-sequence specific interactions of the histones with the phosphate backbone4.

The histones overall are highly basic proteins (positively charged), but they also have patches of hydrophobic and slightly acidic regions. These features would naturally raise the expectation that they would repel each other and would be attracted to acidic molecules, such as nucleic acids (Fig Ic). The two heterodimers of H3–H4 exist as an H3–H4 heterotetramer within the nucleosome, even though their highly basic nature would predict that this would not be the most favorable interaction. Indeed, the association constant of the histone H3–H4 dimer to tetramer transition at physiological ionic strength (neutral pH and between 100–200 mM NaCl) is between 1 and 10 µM for histones from Xenopus laevis98. As expected, the propensity to form H3–H4 tetramers in vitro is highly ionic strength-dependent and increases dramatically to the nanomolar range as the ionic strength rises or with the addition of osmolytes99. Similarly, the association of H2A–H2B dimers with the H3–H4 tetramer is also highly salt-dependent and the histone octamer only exists stably in high ionic strength conditions98 or in association with DNA or other proteins, such as histone chaperones, in vivo. Owing to the strength of the driving force due to electrostatic attraction for histone–DNA binding, the association of histones with DNA easily leads to off pathway irreversible intermediates and malformed nucleosome structures in the absence of histone chaperones or salt.

The need for histone chaperones

From an energetic standpoint, arguably the largest transitions in chromatin dynamics occur during the processes of assembling and disassembling nucleosomes, and not surprisingly, the assembly and disassembly of nucleosomes occurs in a stepwise fashion. It has been generally accepted that some form(s) of the pathway illustrated in Figure 1 operates to construct nucleosomes from component histone dimer precursors (Box 1). The pathway includes the assembly of H3–H4 dimers into H3–H4 tetramers, a process which might occur on the DNA via the sequential deposition of two H3–H4 dimers. Alternatively, the formation of an H3–H4 tetramer could occur on a histone chaperone before being deposited onto the DNA. The result is a heterotetramer of H3–H4 on the DNA, termed a tetrasome, an intermediate which has been observed both in vivo and in vitro (Figure 1)12. Finally, the incorporation of two dimers of H2A–H2B gives rise to the nucleosome core particle12. Given that the two dimers of H2A–H2B occupy opposite sides of the nucleosome and do not physically interact with each other, it is possible that the two H2A–H2B dimers are incorporated in a stepwise manner, giving rise to an intermediate structure with a single H2A–H2B dimer, termed the hexasome (Figure 1). Histones and DNA fail to self-assemble into nucleosomes under physiological conditions because of the strong tendency for histones to associate non-specifically with DNA and form aggregates13. Thus there is a need for histone chaperones to guide the process and each step along the assembly pathway is carefully controlled and regulated by these histone chaperones.

Figure 1. Stepwise assembly and disassembly of nucleosomes mediated by histone chaperones.

DNA is wrapped around two H3–H4 dimers and two H2A–H2B dimers to form the nucleosome core particle. The stepwise assembly, along with the different possible intermediates including the tetrasome and hexasome, are represented here. Histone chaperones mediate each step of the assembly/disassembly process. Histone H2A is depicted in yellow, H2B in red, H3 in blue, and H4 in green.

Structural forms of histone chaperones

Histone chaperones are as varied as the processes they promote. Many specialized chaperones for the histones that form the nucleosome core particle (core histones) and those that interact with the nucleosome core and the linker DNA (linker histones) participate at each step in the processes of nucleosome assembly, disassembly and histone exchange during different genomic processes (Table 1)11, 14. Additionally, specific variant histone chaperones, such as yeast Chz1 and Yaf9, recruit H2AZ, whereas human HJURP recruits the H3 variant CENPA into chromatin15–18. As a group, the histone chaperones have no sequence similarity, but there are several themes that have emerged from recent structural studies. As such, the core histone chaperones will be grouped and discussed below according to their structural motifs (Figure 2 and Table 1).

Table 1.

[SC1]Summary of histone chaperones

| Chaperone Classification |

Histone Chaperone |

Binding Partners |

References | Functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3–H4 Family | Asf1 | H3–H4 dimer HIRA CAF-1 RFC MCMs (via histones) Bdf1 |

100 101 |

Transcriptional regulation Replication Repair Transcriptional silencing Promotes histone acetylation Assembly of senescence associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF) |

100, 50, 1 |

| Vps75 | H3–H4 Rtt109 |

50, 51 50, 51 |

Transcriptional regulation Repair Telomere length maintenance Promotes histone acetylation |

104 105 106 50, 51 |

|

| Rtt106 | H3–H4 CAF-1 |

67 67 |

Replication Transcriptional silencing Transcription repression |

52 67, 68 107, 108 |

|

| CAF-1 | H3–H4 Rtt106 Asf1 HP1 PCNA MBD1 |

74 67 109 110 90 111 |

Replication Repair Transcriptional silencing |

74 112, 113 113, 114 |

|

| HIRA | H3–H4 ASf1 Pax 3 Swi/Snf |

115 116 117 118 |

DNA synthesis independent nucleosome assembly Transcriptional repression Transcriptional silencing Assembly of SAHF Sperm chromatin decondensation |

115 107, 119, 121 122 123 |

|

| RbAp46 RbAp48 dp55 |

Component of HAT1 CAF-1 PRC2 NURF NuRD HDAC1 2, 3 complexes |

124 | Many aspects of chromatin metabolism and histone modification | 124 | |

| FKBP (Fpr 3, 4) | H3–H4 | 125 | rDNA silencing Regulation of histone methylation Cell cycle regulation |

125 126 |

|

| H2A–H2B Family | Nucleolin | H2A–H2B | 127 | Replication Transcription Recombination |

128 |

| PP2Cγ | H2A–H2B | 129 | Dephosphorylation and exchange of H2A–H2B | 129 | |

| H2A–H2B, H3–H4 Family | FACT | H2A–H2B H3–H4 RPA MCMs |

130 | Replication Repair Transcription Recombination |

130 |

| Nucleoplasmin family | H3–H4 (by N1/N2) H2A–H2B (by Np) |

131 | Histone storage Sperm chromatin decompaction Transcription regulation |

131 | |

| DEK | H2A–H2B H3–H4 PKC |

132 and references therein | Transcription, Repair Apoptosis Tumorigenesis Differentiation |

132 and references therein | |

| JDP2 | H2A–H2B H3–H4 c Jun ATF-2 |

133 | Transcription Cell differentiation Cell death HAT inhibitor Tumorigenesis |

133 | |

| ANP32B | H2A–H2B H3–H4 Rep68 KLF5 |

134 | Transcription Apoptosis |

134 | |

| Variant Histone | Chz1 | H2AZ–H2B | 16, 71 | Nuclear import and deposition of H2AZ | 16, 70 |

| Yaf9 | H2AZ–H2B NuA4 subunit SWR1 subunit |

17, 135 | H2AZ deposition onto DNA Transcription regulation |

17, 135 | |

| HJURP | CENPA | 15, 18 | Deposition of CENPA | 15, 18 | |

| Core/Linker Histone | NAP1 | H2A–H2B H3–H4 H1 |

136 | Histone shuttling Linker histone deposition H2AZ exchange Transcription |

136 |

| NASP | H2A–H2B H3–H4 H1 |

79 | Delivery of core histones Deposition of linker histones |

28, 137 |

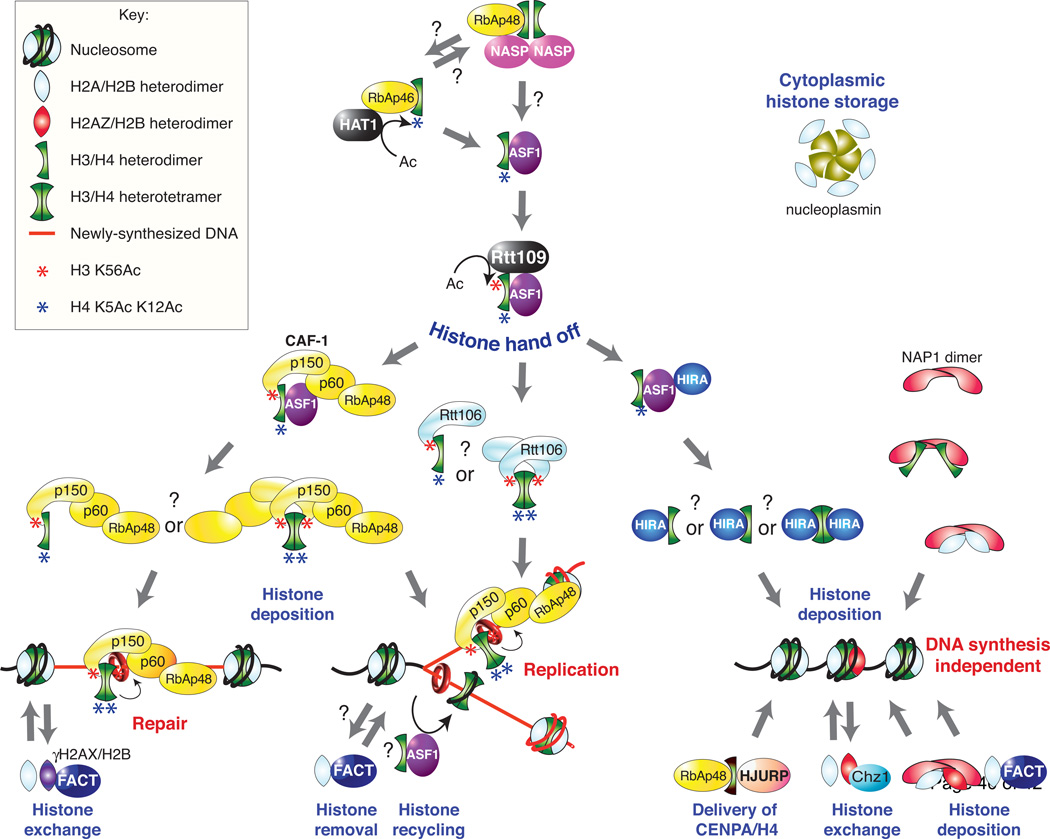

Figure 2. Structural classification of histone chaperones.

(a) β-sandwich structures aligned. The Asf1 N-terminal domain (PDBID: 1ROC) and Yaf9 YEATS domain (PDBID: 3FK3) are represented as ribbons colored blue to red from the N- to the C-terminus of each domain. Structures of Asf1 bound to H3–H4 (PDBID: 2HUE) and ASF1A bound to the B domain of HIRA (PDBID: 2I32) are shown with the histone chaperone colored in magenta, H3 in blue, H4 in green, and the B-domain peptide colored and highlighted in orange. Note that the binding sites for H3–H4 and HIRA are located on the opposite sides of ASF1A. (b) α/β-earmuff histone chaperones. Aligned structures of NAP1 (PDBID: 2AYU) and Vps75 (PDBID: 3DM7) are colored according to secondary structure elements (helix in cyan, beta-strands in magenta and turns in gold). The second view is rotated by 90° about the horizontal axis of the page. The corresponding electrostatic surface diagrams (blue, red and white colors correspond to the electro-positive, electro-negative and neutral charge) highlight the histone binding surfaces with grey ovals indicating the likely positions of H2A–H2B or H3–H4. (c) β-propeller chaperones. The structures of nucleoplasmin (Np, PDBID: 1K5J) and the RbAp46–H4 complex (PDBID: 3CFS) along with electrostatic surface potential diagram (colored as in panel (b)) are illustrated. Nucleoplasmin is a pentamer (subunits colored differently), whereas RbAp46 (magenta) is composed of 7WD repeats. The alpha helical H4 peptide is shown in green. (d) β-barrel and half barrel chaperones. Domains from Pob3 (a FACT subunit) (PDBID: 2GCL) and Rtt106 (PDBID: 3GYP) are represented. The blue oval indicates a likely binding site for H3–H4. The structure of the N terminus of Spt16 (a FACT subunit) (PDBID: 3CB5) has a unique fold. (e) Irregular – Chz1. The structure of H2AZ–H2B bound to Chz1 (PDBID: 2JSS) shows the exposed surface of the H2AZ–H2B dimer in the context of the nucleosome. The view on the right is rotated by 180° about the vertical axis of the page to show the surface of H2AZ–H2B that would be in contact with H3–H4 in the nucleosome. Chz1 is shown in cyan, H2AZ in yellow and H2B in red.

β-sheet sandwich chaperones - Asf1 and the YEATS domain

Anti-silencing function 1 (Asf1) earned its name from the loss of transcriptional repression of the budding yeast silent loci that occurs upon its overexpression19, 20. Yeast Asf1 and human ASF1A were subsequently shown to be histone chaperones21, 22, long before the first structural view revealed a compact Ig-like β-sheet sandwich fold23. This structure included the N-terminal core domain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Asf1 (yAsf1)23 (Figure 2a), but not the extended and intrinsically disordered acidic tail24. The hydrophobic and acidic surface of Asf1 is remarkably conserved among Asf1 homologs, a finding which suggested that it might be the region for histone binding; this hypothesis was confirmed by mutagenesis and NMR chemical shift perturbation23, 25, 26. The monomeric state of Asf1 is maintained in the Asf1–H3–H4 complex, which comprises one molecule of Asf1 and a single H3–H4 dimer27–30. The crystal structure of S. cerevisiae Asf1 in a complex with histones H3 and H4 showed that yAsf1 envelops the C-terminal α-helix of histone H3, blocking H3–H4 tetramer formation (Figure 2a)29. The manner in which Asf1 binds to the histones via a β-sheet addition interaction of the C-terminal tail of H4 with the edge of the yAsf1 β-sheet highlighted the malleability of histone structure, because the same region of H4 forms a mini-β sheet with histone H2A in the context of the nucleosome29, 31. As such, the binding of yAsf1 to a region of H4 that would be exposed with the removal of H2A–H2B from the nucleosome suggested a strand capture mechanism, whereby yAsf1 could access H3–H4 in the context of the tetrasome29. The remarkable structural conservation of the Asf1–H3–H4 complex was apparent from the crystal structure of human ASF1A (also called CIA-I) in complex with histone H3–H430. This study also showed that ASF1A can bind preferentially to the H3–H4 dimer under conditions where H3–H4 tetramers are observed30.

Functional evidence indicates that Asf1 is likely to hand off the H3–H4 dimer to other histone chaperones that lie downstream in the pathway of histone delivery to the DNA. Structural and binding studies of human ASF1A with peptides from the histone chaperones chromatin assembly factor 1 (CAF-1) or histone regulatory homolog A (HIRA) provided insights into how the eukaryotic histone chaperone Asf1 might hand off the dimer of the DNA synthesis-specific variant H3.1–H4 dimer to CAF-1 or the DNA synthesis-independent variant H3.3–H4 dimer to HIRA. Structural analysis showed that the HIRA B domain (amino acid residues 425–472) forms an antiparallel β-hairpin that interacts on the opposite side of the ASF1A β-sandwich from where histone H4 binds to ASF1A (Figure 2a)32. Similar interactions were observed for the orthologous peptide from Schizosaccharomyces pombe Hip1B (amino acid residues 469–497), and interestingly, also for a C-terminal peptide (amino acid residues 493–512) from the p60 subunit of CAF-133. These results explain why CAF-1 and HIRA binding to Asf1 is mutually exclusive and how they might regulate histone deposition in replication-dependent and - independent pathways, respectively.

Yaf9 is a yeast histone chaperone involved in H2AZ acetylation and deposition into euchromatic promoter regions17. The crystal structure of the conserved YEATS domain17 revealed an Ig like β-sandwich fold (Figure 2a). Structurally, Yaf9 is highly similar to yeast Asf1 and has conserved features that indicate potential histone H3–H4 binding sites. Interestingly, Yaf9 is a subunit of both the histone acetyl transferase (HAT) complex NuA4 and the ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler complex SWR1-C17.

α/β-earmuff chaperones - NAP1 and relatives

The nucleosome assembly protein 1 (NAP1) family of histone chaperones34 are involved in histone delivery from the cytoplasm35, 36, binding to histone H137, as well as in assembling37–40 and disassembling nucleosomes34, 41, 42. The structure of yNap1 revealed a previously uncharacterized α/β fold43, 44 (Figure 2b) that has now been observed in Plasmodium falciparum pfNAPL45, inhibitor of acetyltransferases (INHAT; also called SET and TAF-I β)46, and Vacuolar protein sorting 75 (Vps75)47–49. Unlike the β-sandwich family, these chaperones are obligate dimers and use a long α-helix for dimerization and to link the α/β earmuff motifs. The site of histone binding appears to involve the central and bottom surfaces of the earmuff domains, as indicated by the charge distribution on that face and cleft of the proteins and from mutagenesis studies (Figure 2b)43. However, pfNAPL lacks the accessory domain that links domain 1 and 2 and it might have unique histone binding sites45. Vps75 has a slightly closer distance between the earmuff domains than NAP1 due to a shorter dimerization domain and a pronounced cleft at the center of the dimer47–49.

Yeast Vps75 binds H3–H4 and promotes the acetylation of H3 on lysine residue 56 (H3 K56Ac) by the HAT Rtt10950. Similarly, the histone chaperone Asf1 also presents histones H3–H4 to the HAT Rtt109 to achieve acetylation of H3 K5650. However, others have proposed that Asf1 regulates H3 K56 acetylation by presenting the histones to the Vps75–Rtt109 complex rather than to Rtt109 alone51. The involvement of histone chaperones in the acetylation of H3 K56 is intriguing, because this specific histone modification drives the later steps in the chromatin assembly process via its role in increasing the affinity of histones for chaperones that directly deposit the histones onto DNA52, 53 [52, 53]. Biochemical evidence indicates that the earmuff domains of Vps75 are involved in the interaction with Rtt109 (2:1 stoichiometry) and that the central cleft is largely involved in binding to histones47–49 [47–49]. These findings are consistent with a role for Vps75 in chromatin assembly as well as in promoting Rtt109-mediated H3 K56 acetylation in yeast.

β-propeller chaperones

The first histone chaperone structures to be determined were of the β-propeller class. Nucleoplasmin (Np) functions in histone storage during oogenesis, sperm chromatin decompaction and nucleosomal assembly and regulates nucleolar events54. The structure of the N-terminal domain of Np revealed a stable pentamer (Figure 2c) of an eight stranded β barrel motif that self associates to form a decamer55. Similar structures have been solved for dNLP (Drosophila Nucleoplasmin Like Protein)56, Xenopus laevis NO3857 and nucleophosmin (B23)58. The surface charge distribution of these multi-subunit β-propeller proteins has less distinct acidic patches than seen for the other chaperones (Figure 2c). The Np core domain associates cooperatively with linker histones as well as the core histones with mid nanomolar affinities to form complexes with up to five histone octamers, which dock onto the central Np decamer presumably through interactions with the H2A–H2B dimer at the periphery of each pentamer59.

Although it has long been recognized that two of the subunits of CAF-1, p60 and dCAF-1 p55 (also called RbAp48 in humans), belong to the WD-40 repeat family, a novel mode of their histone binding was revealed in recent structural studies (Figure 2c)60, 61. The p55 subunit of Drosophila melanogaster CAF-1 and the RbAp46 protein (which is closely related to human CAF-1 RbAp48) both consist of a seven bladed β-propeller structure with an additional α-helix at the N-terminus60, 61. The surface charge distribution of the two proteins is conserved, with a negatively charged surface at the top and a hydrophobic surface at the bottom60. The N-terminal α-helix of H4 (α1) binds on the edge of the β-propeller between the N-terminal α-helix and a binding loop in an acidic region60, 61 (Figure 2c). Association of p55 or RbAp46 with histone H4 requires a conformation in which the α1-helix of H4 is separated from interactions with the α2-helix and the N-terminal helix of H3, which would disrupt the canonical H3–H4 structure (Box 1)60. Interestingly, CAF-1 p55 binds H3–H4 with high nanomolar affinity that cannot be accounted for by the known interaction with H4 alone; however, the H3 interaction surface is unknown60. The association of this subunit with many chromatin modifying complexes including HAT1 and PRC2 (polycomb repressive complex 2), as well as the chromatin remodeling complexes NURD and NURF, suggests that Drosophila p55 and human RbAp46/48 have a multifunctional role in exposing H3–H4 to these machineries when it is not associated with DNA or H2A–H2B. Indeed, the conformational change in H4 bound to Drosophila p55 and human RbAp46/48 would not be tolerated within the nucleosome60, 61.

β-barrel and half barrel chaperones

FACT (facilitates chromatin transcription) is a heterodimeric histone chaperone composed of the multidomain factors Spt16 (also called Cdc68), Pob3, and Nhp6 (in yeast) or SPT16 and SSRP1 (in metazoans)62. The N-terminal domain of Pob3 is thought to direct heterodimerization through interactions with the middle domain of Spt1663. The structure of the middle domain of Pob3 revealed a double pleckstrin homology (PH) domain64, which has a helix-capped β-barrel architecture that is linked to its role in replication through the binding of the yeast RPA (replication protein A) complex64. The structure of the amino terminal domain of S. pombe and S. cerevisiae Spt16 (Spt16N) is also a novel histone chaperone fold with linked aminopeptidase and pita-bread domains (Figure 2d)65, 66. Biophysical and biochemical studies indicate that Spt16N can bind H3–H4 dimers with either a 1:1 or 2:2 ratio65. Although it primarily binds the histone fold region of H3–H4, the N-terminal tails contribute to binding with weak affinities in the range of 1–10 µM.

The most recently identified member of this structural group is the S. cerevisiae H3–H4 histone chaperone Rtt10652, 67, 68. Rtt106 has a preference for binding to histones that are acetylated on histone H3 K56. This interaction is mediated by its predicted PH domain52, which was shares a similar structure69 with the middle domain of Pob352, 64 (Figure 2d). Mutagenesis studies identified an H3–H4 binding site in a loop in the Rtt106 C-terminal domain that is distinct from a patch of positively charged residues that conferred weak DNA binding affinity69.

Histone variant chaperone Chz1 - irregular structure

In contrast to the structurally defined classes of histone chaperones discussed above, other histone chaperones lack a recognizable sequence or structural motif. Chz1 is one of the two main H2AZ–H2B binding proteins utilized by the SWR1 complex to mediate histone exchange70. However, the association-dissociation rates of H2AZ from NAP1 are lower than that of canonical H2A37, indicating that Chz1 might be a more optimal histone chaperone for H2AZ. The NMR structure of Chz1 in complex with H2AZ–H2B (Figure 2e)16 reveals the irregular structure of Chz1 with interspersed α helices that bind the H2AZ–H2B dimer in an extended conformation mainly on one surface of the dimer16. The affinity is in the high nanomolar range, but interestingly, the complex assembles with a diffusion controlled association rate and dissociates much more slowly at 22s−1 71. These kinetics limit the rate that histones can be delivered to the tetrasome, but interestingly, are in line with the measured values for DNA unfolding from the histones or “breathing” within the nucleosome72.

Implications of oligomeric status of histone chaperones and the surfaces of the histones to which they bind

Several themes have emerged from detailed analyses of histone chaperones. They have different oligomeric states that correlate with their roles in different stages of nucleosome assembly. Moreover, they show a variety of multimeric interactions that involve different regions of the chaperones and different regions of the histones (Table 2). There are generally two types of histone chaperone–histone binding: simple 1:1 or 2:2 with affinity values in the range of 1–100 nM and multimeric histone chaperone–histone complexes in which each individual binding interaction is quite weak (in the range of 0.1–100 µM), but the sum of several binding interactions gives rise to high affinity and specificity.

Table 2.

Oligomeric status and stoichiometry of histone binding to histone chaperones

| Chaperone Structure |

Histone Chaperone |

Oligomeric status |

Stoichiometry of binding (Chaperone: Histone) |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-sheet sandwich | Asf1 | Monomer | 1:1 (H3–H4 dimer) | 23, 25, 27 |

| Yaf9 | Monomer | Unknown | 17 | |

| α/β-earmuff | NAP1 | Dimer | 1:1 (H3–H4, H2A–H2B), 2:1 (H1) | 34 |

| Vps75 | Dimer | 1:1 (H3–H4) | 47 | |

| TAF1β | Dimer | 1:1 (H3–H4) | 46 | |

| β-propeller | Nucleoplasmin family | Pentamer (dimer of pentamers) | 1:1 (H3–H4, H2A–H2B) | 55–58 |

| RbAp46 | Monomer (7 WD repeat domain) | 1:1 (H4) | 60, 61 | |

| β-barrel and half barrel | Rtt106 | Unknown | 1:1 (H3–H4) | 69 |

| Pob3 | Heteroligomer | 1:1 (H3–H4) | 64 | |

| Others | Chz1 | Monomer | 1:1 (H2AZ-H2B) | 16,71 |

| NASP | Dimer | 1:1 (H3-H4, H2A-H2B), 2:1 (H1) | 79,80 |

The monomeric histone chaperones, Asf1 and Chz1, interact with single H3–H4 and H2AZ–H2B dimers, respectively16, 29. However, the location of their binding sites on the histones suggests that they have quite distinct roles in the assembly process. Asf1 blocks H3–H4 tetramer formation by binding the H3 dimerization surface that is normally buried within the histone octamer29. Consequently, the histones as bound to Asf1 present exposed surfaces that will eventually reside on the outside of the octamer, thus enabling Asf1-bound histones to interact with other histone chaperones during the process of histone hand-off (Figure 3). This histone hand-off is also facilitated by the fact that Asf1 has binding sites for other histone chaperones, including CAF-1 and HIRA, to further the assembly process via the formation of intermediate complexes containing multiple histone chaperones (Figures 1 and 3)52. The binding of the largest subunit of yCAF-1 and yRtt106 is enhanced for histone H3 that is acetylated at K5652. The site of this modification is on a surface of H3 that is exposed on the outside of the histone octamer opposite from the H3–H4 dimerization surface to which Asf1 binds (Box 1, Figure I and Figure 2). These observations suggest a model whereby once Asf1 is no longer bound to the histones, CAF-1 and / or Rtt106 could allow the formation of H3–H4 tetramers, perhaps also accompanied by a second molecule of Rtt106 or CAF-1 binding to the second CAF-1 or Rtt106 binding surface of H3 in the H3–H4 tetramer (Figure 3). In support of this model, the p150 subunit of Xenopus CAF-1 has been shown to be a dimer73). Although it has not yet been shown, the histone-binding mode of Rtt106 and CAF-1 might facilitate the formation of the H3–H4 tetramer on the surface of these histone chaperones, prior to being deposited onto the DNA. This model is consistent with the role of chaperones such as Rtt106 and CAF-1 in depositing histones directly onto the DNA52, 67, 74.

Figure 3. Model for the histone chaperone-mediated hand-off during chromatin assembly.

Histone chaperones relay histones to their nucleosomal destination. Some histone chaperones, such as nucleoplasmin, act as a cytosolic histone storage platform. Question marks indicate uncertainty about the exact components of specific protein complexes, or the steps that are likely or suggested from the literature but have not definitively been proven to occur. The red rings around the newly synthesized DNA represent PCNA. The model shown is compiled from experimental evidence derived from yeast and / or higher eukaryotic systems, depending on the available information. In particular, the role of H3 K56Ac in chromatin assembly that is depicted is implied from the findings of studies only in the yeast system to date.

Box 1, Figure I. Chemical nature of histones.

(a) The primary structure of histones H2A (yellow), H2B (red), H3 (blue), and H4 (green). Colored boxes enclose the regions of the histones that are folded in the context of the nucleosome. (b) The three dimensional structures of the H2A–H2B dimer (yellow and red) and H3–H4 dimer (blue and green) are illustrated in two views. The α-helices in H3 and H4 that are referred to in this review are labeled. (c) The distribution of basic and acidic regions of the histones is illustrated in surface renderings of the same views shown in (b). The basic regions are colored in blue, the red regions indicate acidic patches and the white regions indicate neutral and hydrophobic sites.

By contrast to the binding of Asf1 to the buried histone surface, Chz1 binds to a surface of H2AZ–H2B that is exposed in the histone octamer; therefore Chz1 does not block the association of H2AZ–H2B with H3–H4 tetramers or tetrasomes16. This histone-binding mode makes Chz1 perfectly suited for the deposition of histones directly onto tetrasomes (Figure 3). However, the interaction of Chz1 with histones H2AZ–H2B could limit the interaction of DNA with the dimer, perhaps until it is correctly associated with H3–H4. Chz1 has access to the majority of its binding surface on H2A–H2B even in the intact nucleosome; this could explain how Chz1 directly participates in the chromatin disassembly portion of the histone exchange reaction where Chz1 presumably acts as a histone sink during the energy-dependent nucleosome remodeling that is catalyzed by the SWR1 complex16, 70.

The α/β earmuff chaperones are obligate dimers that bind one histone dimer per subunit and can assemble nucleosomes in vitro. Rates of nucleosome assembly, measured by fluorescence anisotropy and electrophoretic mobility shift assays, indicate that NAP1 assembles histone octamers into nucleosomes via detectable hexasome intermediates with H2A–H2B or the H2AZ–H2B variant. These findings indicate that the histone–DNA complexes are all more energetically favorable than the NAP1–histone interactions37. NAP1 also assembles tetrasomes from H3–H4 and DNA, but in the presence of H2A–H2B dimers, the tetrasome intermediate is transient, suggesting that the hexasome is more energetically favorable than the tetrasome. NAP1 also cooperatively binds one histone dimer per subunit with affinities for both H2A–H2B dimers and H3–H4 tetramers between 1–10 nM, weaker than the affinity of the histones for DNA75. Whereas NAP1 appears to be a structure-specific protein that recognizes the histone fold features of the histone, with little discrimination among the different histone types75, Vps75 has specificity for H3–H4 with a similar stoichiometry, but weaker affinity, for histones in the mid-nanomolar range48.

In contrast to NAP1, which appears to bind to any and all histones via a single surface that recognizes the common histone fold, FACT binds multiple different histones concomitantly via multiple interaction domains. The amino terminal domain of Spt16 binds weakly to both the globular domain and the N-terminal tails of histones H3-H465. Meanwhile, other domains of Pob3 and Spt16 each bind to H2A–H2B, giving rise to multimeric interactions between the histones and FACT that will increase the apparent binding affinity through cooperativity. The end product of FACT function on a nucleosome in vitro is the removal of a dimer of histone H2A–H2B, but in vivo FACT is involved in replacing H2A–H2B dimers onto the DNA during transcriptional elongation76, repair and perhaps also replication. Interestingly, FACT appears to induce globally increased accessibility of the DNA throughout the nucleosome in vitro, without the displacement of histones, a process that would be aided by multimeric binding interactions77.

The dCAF-1 p55 and hCAF-1 RbAp48 subunits have a heptameric subdomain structure with a single binding site for H4. There appear to be many other sites on Drosophila p55, human RbAp48 and RbAp46 for interactions with the NURF and NuRD remodeling complexes, PRC278, other CAF-1 subunits, HAT1, and histone H3. In fact, a binding pocket mutant of dCAF-1 p55 cannot form a functional PRC2 complex, but can still interact with HAT1 and histone H3 [60]. The site of binding of Drosophila p55, human RbAp48 and RbAp46 to H4 is on the opposite face of the H3–H4 dimer from the tetramerization interface, indicating that this CAF-1 subunit might be able to access histones as a dimer while they are bound to Asf1 or as a tetramer in the process of depositing the H3–H4 tetramer onto DNA. However, given that histone interaction surfaces also exist on the two other CAF-1 subunits, it is not clear whether the p55 / RbAp48 histone interaction is utilized during CAF-1 mediated chromatin assembly. Instead, the p55 / RbAp48 histone interaction might be more relevant to other steps during the histone delivery and chromatin assembly pathway, including acetylation of histone H4 by HAT1 or the deposition of CENPA/H4 into centromeres by human HJURP (Figure 3).

The biological assembly of Nucleoplasmin family members is a dimer of pentamers. Complete octamers can be assembled from H3–H4 tetramers and H2A–H2B dimers by this class of chaperones in vitro and modeling studies have suggested that each face of the Np monomer could bind a histone octamer54. Np and N1 bind H2A–H2B dimers and H3/H4 tetramers, respectively, and buffer the storage pool of histones in Xenopus oocytes and eggs (Figure 3). NASP (nuclear autoantigenic sperm protein), a dimeric protein79 that specifically binds histones H3/H4 and can promote nucleosome assembly of nucleosomes80, also mediates the proper incorporation of histone H179, 81. Human NASP is present with H3–H4 in various multichaperone complexes, including combinations of other H3–H4 chaperones such as CAF-1, HIRA, Asf1 and RbAp4828, 82.

The nucleosome assembly process

Multiple steps, in parallel pathways, lead to the formation of the ultimate product of chromatin assembly - the nucleosome core particle (Figure 3). The incorporation of specific histone post-translational modifications and the hand-off or “shuffle” of the histones between histone chaperones are common themes along these pathways. Histones H2A–H2B and H3–H4 are delivered via distinct pathways that usually utilize distinct histone chaperones, coming together only on the DNA.

Arguably the earliest step along the pathway towards chromatin assembly is the heterodimerization of H3 with H4, and H2A with H2B. The proteins that are involved in the formation of the histone dimer units of chromatin, if any, are currently unknown. While still in the cytoplasm, histone H3–H4 dimers are acetylated by the HAT1–RbAp48 complex, specifically on lysine residues 4 and 12 within the N-terminal tail of histone H483. The exact function of these acetylation marks remains unclear. The majority of histones H3 and H4 appear to be handed off to Asf1 and as yet uncharacterized, histone chaperone complexes that include subsets of the histone H3–H4 chaperones Asf1, RbAp48 and NASP28, 82, 84. From the central Asf1 histone chaperone, histones H3–H4 are next handed off to one of several downstream H3– H4 chaperones including CAF-1 and yRtt106, which mediate chromatin assembly following DNA synthesis, and HIRA which mediates chromatin assembly that occurs outside of DNA synthesis (Figure 3). The choice of downstream H3–H4 chaperone depends on the variant of H3 that is present in the H3–H4 dimer, at least in higher eukaryotes. The DNA synthesis-specific histone variant H3.1 is only 4 or 5 amino acids different from the DNA synthesis-independent histone variant H3.3 in Drosophila and humans respectively, but this is sufficient to specifically target H3.1 to CAF-1, whereas H3.3 is targeted to HIRA28, 85. The single canonical H3 in budding yeast more closely resembles H3.3 than H3.1 and seemingly all yeast H3 is acetylated on lysine 56 by Rtt109 while the H3–H4 dimers are still bound to Asf1. This specific acetylation mark greatly increases the preference of yCAF-1 and yRtt106 for modified H3–H4 dimers52. In the case of CAF-1, which is physically associated with sites of ongoing DNA synthesis via its interaction with proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), the H3 K56Ac mark drives chromatin assembly during DNA repair and DNA replication in yeast52, 53.

Whether H3 K56Ac also drives chromatin assembly following DNA synthesis in humans has not yet been tested. The H3 K56Ac mark is less easily detectable in humans as compared to yeast, suggesting that it is either highly dynamic or merely much less abundant in humans86, 87. Consistent with H3 K56Ac potentially playing a role in driving chromatin assembly following replication in human cells, the abundance of H3 K56Ac peaks in S phase is consistent with it being a mark of newly-synthesized free histones88. Although another group was unable to observe the S phase peak of H3 K56Ac in humans89, the histones contained in affinity-purified complexes of cytoplasmic ASF1B from S-phase human cells carry the typical marks of newly synthesized histones as well as low levels of H3 K56Ac and the nuclear importer importin-484.

The histone hand-off between the histone chaperones is facilitated by several factors. Strikingly, the specific acetylation mark that is promoted by Asf1, H3 K56Ac, also increases the likelihood that the histones will be transferred from Asf1 to CAF-1 or Rtt10652. The physical interaction between Asf1 and CAF-1 or Asf1 and the yeast Hir complex or HIRA presumably facilitates their acceptance of the histones. The mutually exclusive nature of the interactions between Asf1 and CAF-1 and Asf1 and HIRA might also present a point of regulation of the histone flux down either the DNA synthesis-dependent (CAF-1) or synthesis-independent (HIRA) histone deposition pathways (Figure 3)29, 32, 33. Finally, the fact that the histones bind Asf1 in a manner that exposes the particular histone binding surfaces that are used by CAF-1, Rtt106 and perhaps also HIRA, further facilitates the histone hand-off process. Once the histone H3–H4 and H2A–H2B dimers have reached the histone chaperones that will ultimately place them onto the DNA, there are presumably mechanisms to increase their local concentration or to recruit the histone chaperone–histone complexes to appropriate locations on the DNA. In the case of CAF-1, this appears to be mediated via its interaction with the DNA synthesis machinery component PCNA90, 91.

Disassembly of nucleosomes

Chromatin disassembly appears to be the stepwise opposite of the assembly process with one major difference42 being that nucleosome disassembly is an intrinsically energetically unfavorable process. The requirement for ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes for chromatin disassembly is understandable42, given the need to break the histone–DNA contacts to allow removal of the histones by the histone chaperones. Although the basic steps and players are beginning to be uncovered, there is a great deal to learn regarding the regulation of nucleosome disassembly and the decision-making process for disassembling nucleosomes versus exchanging histones. Similar to the assembly process, post-translational histone modifications and histone chaperone availability will likely be crucial for altering either the equilibria that determine H2A–H2B removal and deposition and / or H3–H4 removal and deposition. For example, if the equilibrium for H2A–H2B is tipped towards its removal from DNA, but the H3– H4 equilibrium is unaffected, the likely outcome would be histone exchange. By contrast, if the H3–H4 equilibrium is tipped toward their removal from DNA, the end result would be chromatin disassembly. One example is provided by H3 K56Ac within promoter regions: this mark appears to tip the equilibrium towards H3–H4 removal from the DNA. This event drives rapid nucleosome disassembly from promoters, where H3 K56Ac acts in a combinatorial manner with other chromatin changes which occur at the promoter during transcriptional activation92. In theory, this balance between histone removal and histone occupancy on the DNA could be influenced by altering the histone–histone chaperone interaction, the histone–DNA interaction, or the histone–histone interactions themselves.

Histone chaperone-guided folding pathways

The histone hand-off during assembly must be energetically favorable. Although it is convenient to think of nucleosome assembly as a step-wise process (Figure 1), highlighting the central role that chaperones play in the pathway, the “nucleosome assembly funnel” (Figure 4) provides a thermodynamic perspective to the process. In this view, which is analogous to the protein folding problem, histone chaperones perform functions similar to those of protein folding chaperones in guiding the folding process along the correct pathways by preventing deleterious off-pathway excursions into kinetically trapped intermediates93. Here, the histones begin the assembly process with a “high” free energy and the ability to adopt a wide variety of states and pathways, and as they interact with chaperones and become covalently modified and are assembled into more stable intermediates, they approach a single or smaller number of lowest energy structures, e.g. the nucleosome core particle. Certainly H3 K56Ac promotes histone interactions with CAF-1, which is farther down the folding pathway than Asf1. After nucleosome formation, the modification will be removed to reduce the disassembly of nucleosomes from the DNA. Another example is the acetylation mark on histone H4 K91 which is found on free histones94 at the interface between H3–H4 and H2A–H2B and appears to reduce the affinity of H2A–H2B for H3–H4, and is removed later during the chromatin assembly process.

Figure 4. Histone chaperone mediated “nucleosome assembly funnel”.

Analogous to the protein-folding funnel, the stages of nucleosome assembly are represented here with a funnel. DNA and H2A–H2B and H3–H4 dimers, the more dynamic entities in a higher free energy state, exist at the top of the funnel. Histone chaperones facilitate the assembly of histones and DNA into more stable intermediates (such as the tetrasome) and finally into the fully assembled nucleosome core particle, which is depicted as thermodynamically the most stable state and hence at the bottom of the funnel. Histone chaperones ensure an ordered nucleosomal assembly pathway and prevent histones from getting trapped in local minima during the process. The red star denotes H3 K56Ac. The purple oval and orange arc represent single subunit chaperones, the cyan objects represent chaperones that have multimeric or multi-subunit interactions with histones, and the grey pentamer represents the pentameric or decameric histone chaperones.

Along the way, the histones are subject to many incorrect nonspecific interactions with other charged species in the cell, which due to their highly basic character can result in quite stable intermediates in low-energy local minima or kinetic traps. It is these off-pathway intermediates, which can be difficult or impossible to escape from, that histone chaperones help shield histones from in the cell. Therefore, due to the energetically downhill process of nucleosome assembly, dynamic equilibria theoretically can regulate the ordered assembly. Importantly, the functions of histone chaperones are intimately connected with that of ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers (which utilize the energy from ATP-hydrolysis to break histone–DNA contacts during chromatin disassembly or assembly)95. These molecular machines would be important in cases where disassembly, reorganization or rescue from kinetically trapped intermediate states is required. Their action would effectively raise the energy of the intermediates, giving them more degrees of freedom and the ability to enter new states or follow different pathways.

Concluding remarks

Histone chaperones are key players involved in maintaining histone stability and dynamics in the cell. Structural, biophysical and biochemical information on histone chaperones is beginning to shape a new understanding of the integrated mechanisms of action for this important family of proteins (Box 2). The varied structural motifs and oligomeric states drive electrostatic and conformation-specific interactions between histone chaperones and different faces of the histones, resulting in a shuttling back and forth from one face to another to facilitate an ordered assembly and disassembly process. Covalent modifications shift the histone binding equilibria among the histone chaperones toward different favored binding partners until a more stable state is reached, such as an assembled and positioned nucleosome.

Text box 2: Future Perspectives.

Recent insights into the structures of proteins involved in nucleosome assembly and the nature of some of the intermediate states of the histones, for example the role of H3 K56ac in altering the preference of histone chaperones, are shaping general models for the functions of histone chaperones. However, several questions pertaining to the mechanism of chaperone function remain to be still elucidated:

How does post-translational modification of histones and chaperones regulate their interaction?

Does the H3–H4 tetramer disassemble into H3–H4 dimers during chromatin disassembly, and if so, how does this occur?

How do the variant histone chaperones recognize specific histone variants for their function in specific chromatin domains?

Do histone chaperones act as temporary storage of histones in a passive role, or do they influence the activities of remodeling machineries or chromatin modifying enzymes?

What are the quantitative equilibria that describe the processes involved in chromatin assembly and disassembly, which remain unknown?

Acknowledgements

Due to limitations on the number of references, we were unable to directly cite all of the relevant literature, and many relevant references can be found within the cited references. We are grateful to members of the Churchill and Tyler labs for their suggestions for the manuscript. We are especially grateful to Siddhartha Roy for assistance with the figures. We acknowledge support from NIH GM and NCI to JKT, NIH GM to MEAC and a Susan Komen Fellowship to CD.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Olins AL, Olins DE. Spheroid chromatin units (v bodies) Science. 1974;183:330–332. doi: 10.1126/science.183.4122.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kornberg RD. Chromatin structure: a repeating unit of histones and DNA. Science. 1974;184:868–871. doi: 10.1126/science.184.4139.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kornberg RD. Structure of chromatin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1977;46:931–954. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.46.070177.004435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luger K, et al. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Holde KE. Chromatin. Springer-Verlag; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choudhary P, Varga-Weisz P. ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling: action and reaction. Subcell Biochem. 2007;41:29–43. doi: 10.1007/1-4020-5466-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campos EI, Reinberg D. Histones: annotating chromatin. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:559–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.032608.103928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis RJ. Molecular chaperones: assisting assembly in addition to folding. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laskey RA, et al. Nucleosomes are assembled by an acidic protein which binds histones and transfers them to DNA. Nature. 1978;275:416–420. doi: 10.1038/275416a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Koning L, et al. Histone chaperones: an escort network regulating histone traffic. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:997–1007. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eitoku M, et al. Histone chaperones: 30 years from isolation to elucidation of the mechanisms of nucleosome assembly and disassembly. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:414–444. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7305-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gruss C, Sogo JM. Chromatin replication. Bioessays. 1992;14:1–8. doi: 10.1002/bies.950140102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tyler JK. Chromatin assembly. Cooperation between histone chaperones and ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling machines. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:2268–2274. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ransom M, et al. Chaperoning histones during DNA replication and repair. Cell. 2010;140:183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunleavy EM, et al. HJURP is a cell-cycle-dependent maintenance and deposition factor of CENP-A at centromeres. Cell. 2009;137:485–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou Z, et al. NMR structure of chaperone Chz1 complexed with histones H2A.Z-H2B. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:868–869. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang AY, et al. Asf1-like structure of the conserved Yaf9 YEATS domain and role in H2A.Z deposition and acetylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21573–21578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906539106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foltz DR, et al. Centromere-specific assembly of CENP-a nucleosomes is mediated by HJURP. Cell. 2009;137:472–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le S, et al. Two new S-phase-specific genes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1997;13:1029–1042. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19970915)13:11<1029::AID-YEA160>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singer MS, et al. Identification of high-copy disruptors of telomeric silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1998;150:613–632. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.2.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tyler JK, et al. The RCAF complex mediates chromatin assembly during DNA replication and repair. Nature. 1999;402:555–560. doi: 10.1038/990147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munakata T, et al. A human homologue of yeast anti-silencing factor has histone chaperone activity. Genes Cells. 2000;5:221–233. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daganzo SM, et al. Structure and function of the conserved core of histone deposition protein Asf1. Curr Biol. 2003;13:2148–2158. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Umehara T, et al. Polyanionic stretch-deleted histone chaperone cia1/Asf1p is functional both in vivo and in vitro. Genes Cells. 2002;7:59–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1356-9597.2001.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mousson F, et al. Structural basis for the interaction of Asf1 with histone H3 and its functional implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:5975–5980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500149102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agez M, et al. Structure of the histone chaperone ASF1 bound to the histone H3 C-terminal helix and functional insights. Structure. 2007;15:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.English CM, et al. ASF1 Binds to a Heterodimer of Histones H3 and H4: A Two-Step Mechanism for the Assembly of the H3-H4 Heterotetramer on DNA. Biochemistry. 2005;44:13673–13682. doi: 10.1021/bi051333h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tagami H, et al. Histone H3.1 and H3.3 complexes mediate nucleosome assembly pathways dependent or independent of DNA synthesis. Cell. 2004;116:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.English CM, et al. Structural basis for the histone chaperone activity of Asf1. Cell. 2006;127:495–508. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Natsume R, et al. Structure and function of the histone chaperone CIA/ASF1 complexed with histones H3 and H4. Nature. 2007;446:338–341. doi: 10.1038/nature05613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luger K, et al. Characterization of nucleosome core particles containing histone proteins made in bacteria. J Mol Biol. 1997;272:301–311. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang Y, et al. Structure of a human ASF1a-HIRA complex and insights into specificity of histone chaperone complex assembly. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:921–929. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malay AD, et al. Crystal structures of fission yeast histone chaperone Asf1 complexed with the Hip1 B-domain or the Cac2 C terminus. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:14022–14031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800594200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park YJ, Luger K. Structure and function of nucleosome assembly proteins. Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;84:549–558. doi: 10.1139/o06-088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ito T, et al. Drosophila NAP-1 is a core histone chaperone that functions in ATP-facilitated assembly of regularly spaced nucleosomal arrays. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3112–3124. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosammaparast N, et al. A role for nucleosome assembly protein 1 in the nuclear transport of histones H2A and H2B. EMBO J. 2002;21:6527–6538. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mazurkiewicz J, et al. On the mechanism of nucleosome assembly by histone chaperone NAP1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16462–16472. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511619200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishimi Y, Kikuchi A. Identification and molecular cloning of yeast homolog of nucleosome assembly protein I which facilitates nucleosome assembly in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:7025–7029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang L, et al. Histones in transit: cytosolic histone complexes and diacetylation of H4 during nucleosome assembly in human cells. Biochemistry. 1997;36:469–480. doi: 10.1021/bi962069i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walter PP, et al. Stimulation of transcription factor binding and histone displacement by nucleosome assembly protein 1 and nucleoplasmin requires disruption of the histone octamer. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6178–6187. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma N, Nyborg JK. The coactivators CBP/p300 and the histone chaperone NAP1 promote transcription-independent nucleosome eviction at the HTLV-1 promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7959–7963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800534105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lorch Y, et al. Chromatin remodeling by nucleosome disassembly in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3090–3093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511050103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park YJ, Luger K. The structure of nucleosome assembly protein 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1248–1253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508002103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park YJ, et al. A beta-hairpin comprising the nuclear localization sequence sustains the self-associated states of nucleosome assembly protein 1. J Mol Biol. 2008;375:1076–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gill J, et al. Crystal structure of malaria parasite nucleosome assembly protein: distinct modes of protein localization and histone recognition. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:10076–10087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808633200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muto S, et al. Relationship between the structure of SET/TAF-Ibeta/INHAT and its histone chaperone activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4285–4290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603762104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang Y, et al. Structure of Vps75 and implications for histone chaperone function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12206–12211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802393105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berndsen CE, et al. Molecular functions of the histone acetyltransferase chaperone complex Rtt109-Vps75. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:948–956. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park YJ, et al. Histone chaperone specificity in Rtt109 activation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:957–964. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsubota T, et al. Histone H3-K56 acetylation is catalyzed by histone chaperone-dependent complexes. Mol Cell. 2007;25:703–712. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Han J, et al. Acetylation of lysine 56 of histone H3 catalyzed by RTT109 and regulated by ASF1 is required for replisome integrity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28587–28596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702496200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li Q, et al. Acetylation of histone H3 lysine 56 regulates replication-coupled nucleosome assembly. Cell. 2008;134:244–255. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen CC, et al. Acetylated lysine 56 on histone H3 drives chromatin assembly after repair and signals for the completion of repair. Cell. 2008;134:231–243. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Akey CW, Luger K. Histone chaperones and nucleosome assembly. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:6–14. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dutta S, et al. The crystal structure of nucleoplasmin-core: implications for histone binding and nucleosome assembly. Mol Cell. 2001;8:841–853. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00354-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Namboodiri VM, et al. The crystal structure of Drosophila NLP-core provides insight into pentamer formation and histone binding. Structure. 2003;11:175–186. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Namboodiri VM, et al. The structure and function of Xenopus NO38-core, a histone chaperone in the nucleolus. Structure. 2004;12:2149–2160. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee HH, et al. Crystal structure of human nucleophosmin-core reveals plasticity of the pentamer-pentamer interface. Proteins. 2007;69:672–678. doi: 10.1002/prot.21504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taneva SG, et al. A mechanism for histone chaperoning activity of nucleoplasmin: thermodynamic and structural models. J Mol Biol. 2009;393:448–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Song JJ, et al. Structural basis of histone H4 recognition by p55. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1313–1318. doi: 10.1101/gad.1653308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murzina NV, et al. Structural basis for the recognition of histone H4 by the histone-chaperone RbAp46. Structure. 2008;16:1077–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Belotserkovskaya R, et al. Transcription through chromatin: understanding a complex FACT. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1677:87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.O'Donnell AF, et al. Domain organization of the yeast histone chaperone FACT: the conserved N-terminal domain of FACT subunit Spt16 mediates recovery from replication stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5894–5906. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.VanDemark AP, et al. The structure of the yFACT Pob3-M domain, its interaction with the DNA replication factor RPA, and a potential role in nucleosome deposition. Mol Cell. 2006;22:363–374. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stuwe T, et al. The FACT Spt16"peptidase" domain is a histone H3-H4 binding module. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8884–8889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712293105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.VanDemark AP, et al. Structural and functional analysis of the Spt16p N-terminal domain reveals overlapping roles of yFACT subunits. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:5058–5068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huang S, et al. Rtt106p is a histone chaperone involved in heterochromatin-mediated silencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13410–13415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506176102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huang S, et al. A novel role for histone chaperones CAF-1 and Rtt106p in heterochromatin silencing. EMBO J. 2007;26:2274–2283. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu Y, et al. Structural analysis of Rtt106p reveals a DNA-binding role required for heterochromatin silencing. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:4251–4262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.055996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Luk E, et al. Chz1, a nuclear chaperone for histone H2AZ. Mol Cell. 2007;25:357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hansen DF, et al. Binding kinetics of histone chaperone Chz1 and variant histone H2A.Z-H2B by relaxation dispersion NMR spectroscopy. J Mol Biol. 2009;387:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li G, et al. Rapid spontaneous accessibility of nucleosomal DNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:46–53. doi: 10.1038/nsmb869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Quivy JP, et al. Dimerization of the largest subunit of chromatin assembly factor 1: importance in vitro and during Xenopus early development. EMBO J. 2001;20:2015–2027. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smith S, Stillman B. Purification and characterization of CAF-I, a human cell factor required for chromatin assembly during DNA replication in vitro. Cell. 1989;58:15–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90398-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Andrews AJ, et al. A thermodynamic model for Nap1-histone interactions. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32412–32418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805918200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fleming AB, et al. H2B ubiquitylation plays a role in nucleosome dynamics during transcription elongation. Mol Cell. 2008;31:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xin H, et al. yFACT induces global accessibility of nucleosomal DNA without H2A-H2B displacement. Mol Cell. 2009;35:365–376. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hansen KH, et al. A model for transmission of the H3K27me3 epigenetic mark. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1291–1300. doi: 10.1038/ncb1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Finn RM, et al. sNASP, a histone H1-specific eukaryotic chaperone dimer that facilitates chromatin assembly. Biophys J. 2008;95:1314–1325. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.130021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang H, et al. Expanded binding specificity of the human histone chaperone NASP. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:5763–5772. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Richardson RT, et al. Nuclear autoantigenic sperm protein (NASP), a linker histone chaperone that is required for cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21526–21534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603816200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Groth A, et al. Human Asf1 Regulates the Flow of S Phase Histones during Replicational Stress. Mol Cell. 2005;17:301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Parthun MR. Hat1: the emerging cellular roles of a type B histone acetyltransferase. Oncogene. 2007;26:5319–5328. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jasencakova Z, et al. Replication Stress Interferes with Histone Recycling and Predeposition Marking of New Histones. Mol Cell. 37:736–743. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ahmad K, Henikoff S. The histone variant H3.3 marks active chromatin by replication-independent nucleosome assembly. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1191–1200. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00542-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Das C, et al. CBP/p300-mediated acetylation of histone H3 on lysine 56. Nature. 2009;459:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature07861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xie W, et al. Histone h3 lysine 56 acetylation is linked to the core transcriptional network in human embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell. 2009;33:417–427. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yuan J, et al. Histone H3-K56 acetylation is important for genomic stability in mammals. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1747–1753. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.11.8620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tjeertes JV, et al. Screen for DNA-damage-responsive histone modifications identifies H3K9Ac and H3K56Ac in human cells. EMBO J. 2009;28:1878–1889. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shibahara K, Stillman B. Replication-dependent marking of DNA by PCNA facilitates CAF-1-coupled inheritance of chromatin. Cell. 1999;96:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80661-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang Z, et al. PCNA connects DNA replication to epigenetic inheritance in yeast. Nature. 2000;408:221–225. doi: 10.1038/35041601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Williams SK, et al. Acetylation in the globular core of histone H3 on lysine-56 promotes chromatin disassembly during transcriptional activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9000–9005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800057105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ma B, et al. Folding funnels and binding mechanisms. Protein Eng. 1999;12:713–720. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.9.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ye J, et al. Histone H4 lysine 91 acetylation a core domain modification associated with chromatin assembly. Mol Cell. 2005;18:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Haushalter KA, Kadonaga JT. Chromatin assembly by DNA-translocating motors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:613–620. doi: 10.1038/nrm1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Arents G, et al. The nucleosomal core histone octamer at 3.1 A resolution: a tripartite protein assembly and a left-handed superhelix. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:10148–10152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Arents G, Moudrianakis EN. The histone fold: a ubiquitous architectural motif utilized in DNA compaction and protein dimerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:11170–11174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Karantza V, et al. Thermodynamic studies of the core histones: pH and ionic strength effects on the stability of the (H3-H4)/(H3-H4)2 system. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2037–2046. doi: 10.1021/bi9518858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hoch DA, et al. Protein-protein Forster resonance energy transfer analysis of nucleosome core particles containing H2A and H2A.Z. J Mol Biol. 2007;371:971–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mousson F, et al. The histone chaperone Asf1 at the crossroads of chromatin and DNA checkpoint pathways. Chromosoma. 2007;116:79–93. doi: 10.1007/s00412-006-0087-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Groth A, et al. Regulation of replication fork progression through histone supply and demand. Science. 2007;318:1928–1931. doi: 10.1126/science.1148992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Schneider J, et al. Rtt109 is required for proper H3K56 acetylation: a chromatin mark associated with the elongating RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37270–37274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600265200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Recht J, et al. Histone chaperone Asf1 is required for histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation, a modification associated with S phase in mitosis and meiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6988–6993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601676103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Selth LA, et al. An rtt109-independent role for vps75 in transcription-associated nucleosome dynamics. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4220–4234. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01882-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jessulat M, et al. Interacting proteins Rtt109 and Vps75 affect the efficiency of non-homologous end-joining in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;469:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Selth L, Svejstrup JQ. Vps75, a new yeast member of the NAP histone chaperone family. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12358–12362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C700012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fillingham J, et al. Two-color cell array screen reveals interdependent roles for histone chaperones and a chromatin boundary regulator in histone gene repression. Mol Cell. 2009;35:340–351. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Imbeault D, et al. The Rtt106 histone chaperone is functionally linked to transcription elongation and is involved in the regulation of spurious transcription from cryptic promoters in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:27350–27354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800147200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tyler JK, et al. Interaction between the Drosophila CAF-1 and ASF1 chromatin assembly factors. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6574–6584. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.19.6574-6584.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Murzina N, et al. Heterochromatin dynamics in mouse cells: interaction between chromatin assembly factor 1 and HP1 proteins. Mol Cell. 1999;4:529–540. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Reese BE, et al. The methyl-CpG binding protein MBD1 interacts with the p150 subunit of chromatin assembly factor 1. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3226–3236. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.9.3226-3236.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gaillard PH, et al. Chromatin assembly coupled to DNA repair: a new role for chromatin assembly factor I. Cell. 1996;86:887–896. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kaufman PD, et al. Ultraviolet radiation sensitivity and reduction of telomeric silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells lacking chromatin assembly factor-I. Genes Dev. 1997;11:345–357. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Enomoto S, et al. RLF2, a subunit of yeast chromatin assembly factor-I, is required for telomeric chromatin function in vivo. Genes Dev. 1997;11:358–370. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ray-Gallet D, et al. HIRA is critical for a nucleosome assembly pathway independent of DNA synthesis. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1091–1100. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00526-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sharp JA, et al. Yeast histone deposition protein Asf1p requires Hir proteins and PCNA for heterochromatic silencing. Curr Biol. 2001;11:463–473. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Magnaghi P, et al. HIRA, a mammalian homologue of Saccharomyces cerevisiae transcriptional co-repressors, interacts with Pax3. Nat Genet. 1998;20:74–77. doi: 10.1038/1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Dimova D, et al. A role for transcriptional repressors in targeting the yeast Swi/Snf complex. Mol Cell. 1999;4:75–83. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80189-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sherwood PW, Osley MA. Histone regulatory (hir) mutations suppress delta insertion alleles in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1991;128:729–738. doi: 10.1093/genetics/128.4.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Blackwell C, et al. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe HIRA-like protein Hip1 is required for the periodic expression of histone genes and contributes to the function of complex centromeres. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4309–4320. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4309-4320.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kaufman PD, et al. Hir proteins are required for position-dependent gene silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the absence of chromatin assembly factor I. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4793–4806. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zhang R, et al. Formation of MacroH2A-containing senescence-associated heterochromatin foci and senescence driven by ASF1a and HIRA. Dev Cell. 2005;8:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Loppin B, et al. The histone H3.3 chaperone HIRA is essential for chromatin assembly in the male pronucleus. Nature. 2005;437:1386–1390. doi: 10.1038/nature04059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hennig L, et al. MSI1-like proteins: an escort service for chromatin assembly and remodeling complexes. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kuzuhara T, Horikoshi M. A nuclear FK506-binding protein is a histone chaperone regulating rDNA silencing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:275–283. doi: 10.1038/nsmb733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Nelson CJ, et al. Proline isomerization of histone H3 regulates lysine methylation and gene expression. Cell. 2006;126:905–916. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Angelov D, et al. Nucleolin is a histone chaperone with FACT-like activity and assists remodeling of nucleosomes. EMBO J. 2006;25:1669–1679. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Mongelard F, Bouvet P. Nucleolin: a multiFACeTed protein. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kimura H, et al. A novel histone exchange factor, protein phosphatase 2Cgamma, mediates the exchange and dephosphorylation of H2A-H2B. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:389–400. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Reinberg D, Sims RJ., 3rd de FACTo nucleosome dynamics. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23297–23301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Frehlick LJ, et al. New insights into the nucleophosmin/nucleoplasmin family of nuclear chaperones. Bioessays. 2007;29:49–59. doi: 10.1002/bies.20512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sawatsubashi S, et al. A histone chaperone DEK, transcriptionally coactivates a nuclear receptor. Genes Dev. 2010;24:159–170. doi: 10.1101/gad.1857410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Jin C, et al. Regulation of histone acetylation and nucleosome assembly by transcription factor JDP2. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:331–338. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Munemasa Y, et al. Promoter region-specific histone incorporation by the novel histone chaperone ANP32B and DNA-binding factor KLF5. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:1171–1181. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01396-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Zhang H, et al. The Yaf9 component of the SWR1 and NuA4 complexes is required for proper gene expression, histone H4 acetylation, and Htz1 replacement near telomeres. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9424–9436. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9424-9436.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Zlatanova J, et al. Nap1: taking a closer look at a juggler protein of extraordinary skills. FASEB J. 2007;21:1294–1310. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7199rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Jasencakova Z, et al. Replication Stress Interferes with Histone Recycling and Predeposition Marking of New Histones. Mol Cell. 2010;37:736–743. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]