Abstract

Rationale

A rich literature suggests that both impulsiveness and drug-induced euphoria are risk factors for drug abuse. However, few studies have examined whether sensitivity to the euphoric effects of stimulants is related to attention lapses, a behavioral measure of inattention sometimes associated with impulsivity.

Objective

The aim of the study was to examine ratings of d-amphetamine drug liking among individuals with high, moderate, and low attention lapses.

Methods

Ninety-nine healthy volunteers were divided into three equal-sized groups based on their performance on a measure of lapses of attention. The groups, who exhibited low, medium, and high attention lapses (i.e., long reaction times) on a simple reaction time task, were compared on their subjective responses (i.e., ratings of liking and wanting more drug) after acute doses of d-amphetamine (0, 5, 10, and 20 mg).

Results

Subjects who exhibited high lapses liked 20 mg d-amphetamine less than subjects who exhibited low lapses. These subjects also tended to report smaller increases in “wanting more drug” after d-amphetamine.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that participants who exhibit impaired attention may be less sensitive to stimulant-induced euphoria.

Keywords: Inattention d-amphetamine, Reward, Drug liking, Subjective effects, Dopamine, Impulsiveness

Introduction

Susceptibility to use drugs has been linked to two apparently separate processes, impulsiveness or lack of behavioral control and drug-induced euphoria (de Wit and Richards 2004). Impulsiveness refers to a heterogeneous cluster of behaviors relating generally to a lack of control, insensitivity to negative consequences, and an inability to inhibit inappropriate behaviors (de Wit 2009). Greater impulsiveness is typically associated with higher risk for drug use (Tarter et al. 2003). Drug-induced euphoria refers to subjective or mood states that correspond to feelings of well-being that are commonly associated with behavioral preferences for drugs (de Wit and Phan 2009). Interestingly, although both impulsive tendencies and susceptibility to euphoria have been linked to functioning of the dopamine system (Baler and Volkow 2006; Everitt et al. 2008), few studies have examined the two behavioral processes at the same time in the same subjects. Thus, little is known about the relationships between them. Intuitively, it might be predicted that individuals with less behavioral control would be more likely to experience euphoria induced by a drug since both are associated with increased risk for drug abuse. However, it is also possible that individuals who are more impulsive or more distractible experience less euphoria from a drug, which might lead them to consume more of the drug to achieve the desired effect. Alternately, the factors may be unrelated to one another.

Inattentiveness is the inability to maintain focused attention of goal relevant information, as evidenced by attention lapses (Leth-Steensen et al. 2000). There is considerable research linking inattention and impulsivity. Lapses of attention may degrade an individual's ability to inhibit responses, thus resulting in impulsive behavior (Castellanos and Tannock 2002; de Wit 2009; Leth-Steensen et al. 2000). Impulsivity and inattention are core features of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; Castellanos et al. 2006; Castellanos and Tannock 2002; Simmonds et al. 2007), and both are reduced to a similar degree by neurofeedback (Arns et al. 2009; Gevensleben et al. 2009) or methylphenidate (Conners 2002; Spencer et al. 2009). Methylphenidate reduces symptoms of both impulsivity and inattention in accordance with changes in striatal dopamine (Rosa-Neto 2005). Furthermore, attention lapses is correlated with self-reported motor impulsivity (de Wit 2009), and inattentive symptoms were superior to impulsive symptoms in predicting poor performance on a behavioral measure of impulsivity (Gambin and Swiecicka 2009), suggesting that inattention is closely related to other forms of impulsive behaviors and may represent a dimension of impulsivity (de Wit 2009).

Few studies have examined individual differences in cognitive performance (e.g., inattentiveness) in relation to the rewarding or mood-altering effects of drugs. More impulsive animals, as measured by the inability to withhold responses or by delay discounting, exhibit higher rates of drug self-administration (Belin et al. 2008; Perry et al. 2008; Poulos et al. 1998). However, in the animal studies, it is not always clear whether more self-administration indicates greater or lesser rewarding effects of the drug. In an earlier study on humans, we (de Wit et al. 2000) reported a significant relationship between false alarm rate and amphetamine-induced euphoria. Participants who performed more impulsively (i.e., had a higher false alarm rate) on a go-no-go task in the drug-free state experienced less euphoria when they received a single dose of d-amphetamine (20 mg). This suggests that less attentive individuals may also be less sensitive to the rewarding effects of a drug and perhaps reward more generally.

In this analysis, we examined the relationship between lapses in attention and ratings of drug liking after d-amphetamine (5, 10, or 20 mg). Specifically, we grouped individuals based on their performance on the lapses of attention measure into high, moderate, and low levels of attention lapses and compared these groups on measures of drug liking, wanting more, and feeling the effects of the amphetamine. Based on our previous finding (de Wit et al. 2000), we hypothesized that participants with more attention lapses would like d-amphetamine less than participants with fewer attention lapses and that these differences would be most pronounced at the highest dose of d-amphetamine (20 mg). We also hypothesized that the participants with more lapses would “feel” the effects of the drug less and indicate lower ratings of “want more drug” than participants with more lapses.

Materials and methods

Design

This analysis was conducted using data from a larger study on the genetic basis of response to d-amphetamine (Lott et al. 2005) using a four-session crossover design. Healthy young adults received placebo and three doses of d-amphetamine (5, 10, and 20 mg oral) in randomized order and under double-blind conditions. Subjective, physiological, and behavioral effects of d-amphetamine were recorded over 4 h after drug administration.

Participants

The sample consisted of 99 male (n=50) and female (n= 49) Caucasian volunteers, aged 18–35 (M=22.61, SD=3.60). Volunteers were excluded from participation if their BMI was less than 18 or greater than 26, if they consumed more than three cups of coffee a day or smoked more than ten cigarettes a week, if they had less than a high school education or lack of fluency in English, if they had any serious medical condition, current axis I psychiatric disorder including ADHD (though adult ADHD was not assessed), substance abuse or dependence (APA 1994), or any current or past medical condition that was considered to be a contraindication for amphetamine administration. Women were tested in their follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (White et al. 2002). Subjects were trichotomized into equal low (n=33), moderate (n=33), and high (n=33) attention lapse groups based on their simple reaction time variability (deviation from the modesee below) in the placebo condition.

Measures

Drug Effects Questionnaire

Subjects completed several standardized questionnaires, but here we report only on the Drug Effects Questionnaire (DEQ), which consisted of three visual analog scale items (a 100-mm line) on which subjects rated how much they felt a drug effect, liked the drug, and wanted more of the drug. For each question, an area under the curve (AUC) was calculated separately for 5, 10, and 20 mg d-amphetamine and subtracted from the placebo AUC to create an index of drug effects net placebo responding. It should be noted that these items are based on a simple visual analog scale, and because the participants were not drug users, it should not be considered a measure of drug “craving”.

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale 11

The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale 11 (BIS-11; Patton et al. 1995) is a self-report measure of impulsiveness. Each item is rated on a four-point scale ranging from “rarely/never” to “almost always/always”. The BIS-11 is comprised of three subscales (motor impulsiveness, cognitive/attentional impulsiveness, and nonplanning impulsiveness) which when combined provide a total impulsivity score (BIS total). The BIS-11 is an internally consistent (α=0.79–0.83), valid measure of impulsiveness (Patton et al. 1995). Ninety of the 99 subjects completed the BIS.

Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire

The Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ; Patrick et al. 2002) is a 155-item self-report measure comprising three scales that assess positive emotionality, negative emotionality, and behavioral inhibition (constraint). Higher scores on the constraint scale suggest less impulsivity. For this study, we used only the constraint scale of the MPQ. Eighty-seven of the 99 subjects completed the MPQ.

Profile of Mood States

The Profile of Mood States (POMS; McNair et al. 1971) is a 72-item adjective checklist in which participants rate each adjective in relation to how they feel “right now” using a five-point Likert-scale (0=“not at all” to 4=“extremely”). The items comprise of eight factor-analytically derived scales: anxiety, depression, vigor, anger, fatigue, friendliness, confusion, and elation. From these scales, two higher-order factors of arousal [(anxiety + vigor) − (fatigue + confusion)] and valence [a.k. a. “positive mood” = (elation − depression)] are derived. The POMS positive mood scale was used in the present study. Research supports the utility of this scale as a sensitive measure of mood fluctuation in normal subjects (de Wit et al. 1989).

Simple reaction time task

The simple reaction time (SRT) from the Automated Neuropsychological Assessment Metrics (Reeves et al. 2006) was used to assess lapses in attention. For the SRT, subjects are required to press a key as quickly as possible upon screen presentation of a symbol at variable intervals. From the distribution of reaction times, the mean deviation of the individual reaction times from the modal reaction time was calculated for each subject. The mean deviation from the mode is equivalent to the difference between the mean and the mode of a reaction time distribution, which reflects the proportion of reaction times that are unusually long (lapses in attention; Spencer et al. 2009). Deviation from the mode is one of several acceptable methods (e.g., ex-Gaussian) to characterize RT variability (Leth-Steensen et al. 2000). We chose to use deviation from the mode due to its relative ease of calculation and heartiness to variations in the shape of RT distributions (Hausknecht et al. 2005; Spencer et al. 2009).

Procedure

Subjects first attended an orientation session to provide informed consent and complete some of the trait self-report measures (e.g., BIS, MPQ). They were instructed to abstain from taking drugs including alcohol, nicotine, or caffeine for 24 h before each session and to fast from midnight the night before the sessions. Subjects were tested individually in a comfortably furnished room with television and reading materials for the 4-h session. Subjective and behavioral tasks were administered via computer. This study was approved by the institutional review board of The University of Chicago and was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

Sessions were conducted from 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m., at least 48 h apart. At the beginning of each session, subjects provided breath and urine samples to confirm their drug and alcohol abstinence. Subjects were also given a standard breakfast (granola bar). Volunteers then completed predrug baseline mood questionnaires assessing subjective states. At 9:30 a.m., subjects ingested a capsule containing either placebo or d-amphetamine (5, 10, or 20 mg). Clinically recommended daily doses of d-amphetamine for school-aged children with ADHD range as high as 40 mg (Greenhill et al. 2002; Spencer et al. 2006). The low doses used here minimized risk to subjects while producing measurable effects. Subjective, behavioral, and physiological measures were obtained 30, 60, 90, 150, and 180 min after capsule intake. Of interest for this report was the administration of the simple reaction time task, which was completed once per session at approximately 120 min after ingestion of the capsule.

Data analysis

Preliminary analyses assessed for potential order effects associated with attention lapses on the SRT, the relationship between drug liking and positive mood, group (low, moderate, and high attention lapse groups) differences on the demographic variables of age, gender, and education, and the association between lapses of attention and self-reported impulsivity. Primary analyses then evaluated the attention lapse groups on their responses to d-amphetamine on the three DEQ items (liking drug, wanting more, feeling drug effects) using a 3 (attention lapse group: low, moderate, high)×3 (drug dose 5, 10, and 20 mg d-amphetamine) multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA). Drug dose order was included as the covariate since we were not able to counterbalance the drug order for each group. A multivariate analysis was chosen because preliminary analyses showed that the three outcome measures were moderately correlated with each other at each drug dose (rs=0.16–0.67). Significant multivariate effects were followed up with univariate analyses (ANCOVAS). Significant univariate interactions were probed using simple effects (Girden 1992), while significant univariate main effects and simple effects were probed using Tukey's tests on adjusted means for between subjects (lapse group) variables and Bonferonni corrected t tests for within-subjects (drug dose) variables. Analyses were conducted two-tailed at the 0.05 level of significance. Significant within-subjects effects were tested using the Greenhouse–Geisser correction when violations of sphericity were detected. All uncorrected significant findings remained significant when thus adjusted. We therefore report the degrees of freedom from uncorrected analyses.

Results

Preliminary analyses

To explore the relationship between the behavioral measures of inattention and self-reported impulsivity, attention lapses in the placebo condition (mean deviation from the mode) were correlated with the BIS total and MPQ constraint scores. As predicted, attention lapses were inversely correlated with MPQ constraint (r [87]=−0.24, p<0.05) and also showed a weak, nonsignificant positive relationship with BIS total score (r [90]=0.13, p=0.22). These results provide evidence of the modest association between behavioral and self-report measures of impulsivity, consistent with other reports (Reynolds et al. 2006).

To assess the relationship between mood and drug liking, we correlated POMS positive mood with the drug liking item from the DEQ at each dose of d-amphetamine. As expected, positive mood was significantly correlated with drug liking at 5 mg (r [94]=0.28, p<0.01), 10 mg (r [94]=0.33, p<0.01), and 20 mg (r [94]=0.53, p<0.001) of d-amphetamine.

To assess order effects on attention lapses under placebo conditions, a one-way ANOVA was conducted with placebo order as the independent variable. Attention lapses were not significantly affected by order, F(3, 95)=1.88, p>0.10. Subjects were then divided into equal groups (n=33 per group) of low, moderate, and high attention lapses based on their SRT lapses (deviation from the mode) in the placebo condition. The mean deviations from the mode in these three groups were as follows: high (M=81.65, SD=37.76), moderate (M=34.65, SD=6.25), and low (M=4.53, SD=18.10; ANOVA all p<0.001). The three attention lapse groups did not differ with respect to age, gender, or education level (Table 1; all p>0.48).

Table 1.

Demographic variables as a function of attention lapse group

| Variable | Attention lapse group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Moderate | Low | F/χ2 | |

| Age, M (SD) | 22.39 (4.49) | 23.21 (3.41) | 22.21 (2.71) | 0.72 |

| Gender, N (%) | 0.32 | |||

| Male | 16 (48) | 18 (55) | 16 (48) | |

| Female | 17 (52) | 15(45) | 17 (52) | |

| Education, N (%) | 0.49 | |||

| BA/BS− | 16 (49) | 11 (33) | 16(49) | |

| BA/BS+ | 13(39) | 16(49) | 10(30) | |

| Post Grad | 4(12) | 6(18) | 7(21) | |

BA/BS− did not complete bachelors degree, BA/BS+ completed bachelors degree but no postgraduate education, Post Grad some postgraduate education

To assess for potential group differences in subjective response to placebo, a one-way (group) MANCOVA was performed on the three DEQ items (liking drug, wanting more of the drug, feeling drug) with placebo order as the covariate. The groups differed on one measure of placebo session responses: The high attention lapse group (Madj=1.39, SD=2.84) reported “wanting more” on the placebo compared to the moderate attention lapse group (Madj=−0.88, SD=3.20). The low attention lapse group (Madj=0.27, SD=2.93) did not differ from either of the other groups.

Primary analyses

To assess the separate and combined influences of inattentiveness and drug dose on drug liking, a 3 (group)×3 (drug dose) MANCOVA was performed on the three DEQ items (liking drug, wanting more of the drug, feeling drug) with drug order as the covariate. Results revealed a multivariate main effect of drug dose [Wilks F(6, 90)=3.15, p<0.01] and a nonsignificant multivariate trend for group [Wilks F(6, 186)=1.77, p=0.10]. The effects were limited by a multivariate group by drug dose interaction [Wilks F(12, 180)=1.92, p<0.05]. No other multivariate effect approached significance (all p>0.20; see Table 2 for a list of the adjusted means and standard deviations for the DEQ items).

Table 2.

Meanadj (SD) drug effects questionnaire area under the curve as a function of attention lapses group and d-amphetamine dose

| Variable | Attention lapse group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Madj (SD) | Moderate Madj (SD) | Low Madj (SD) | Total Madj (SD) | |

| Like drug | ||||

| 5 mg AMPH | 0.78 (2.65) | 0.86 (2.38) | 0.90 (3.15) | 0.85 (2.72) |

| 10 mg AMPH | 1.74 (4.19) | 1.24 (2.12) | 1.96 (2.97) | 1.66 (3.19) |

| 20 mg AMPHa | 1.83 (4.32) | 2.82 (3.55) | 4.60 (4.24) | 3.09 (4.17) |

| Total | 1.45 (3.72) | 1.64 (2.68) | 2.50 (3.45) | 1.87 (3.36) |

| Want more | ||||

| 5 mg AMPH | −0.92 (5.24) | 2.57 (5.12) | 1.05 (3.96) | 0.90 (4.95) |

| 10 mg AMPH | 1.37 (5.58) | 3.00 (4.10) | 2.65 (4.74) | 2.34 (4.84) |

| 20 mg AMPH | 2.32 (5.87) | 3.15 (4.67) | 4.38 (5.09) | 3.28 (5.24) |

| Total | 0.92 (5.56) | 2.90 (4.63) | 2.70 (4.59) | 2.17 (5.01) |

| Feel drug | ||||

| 5 mg AMPH | −0.47 (3.40) | 0.57 (2.31) | −0.32 (1.530) | 0.10 (2.54) |

| 10 mg AMPH | 1.30 (3.58) | 1.12 (2.79) | 0.46 (2.81) | 1.54 (3.07) |

| 20 mg AMPH | 2.16 (3.83) | 2.93 (3.89) | 3.03 (3.36) | 1.06 (3.68) |

| Total | −0.08 (3.60) | 0.96 (3.00) | 2.71 (2.56) | 0.90 (3.10) |

Madj means for area under the curve (drug dose) – area under the curve placebo adjusted for order of drug dose presentation, AMPH d-amphetamine, want more want more of the drug, feel drug feel the effects of the drug

Low attention lapses > high attention lapses (p<0.05)

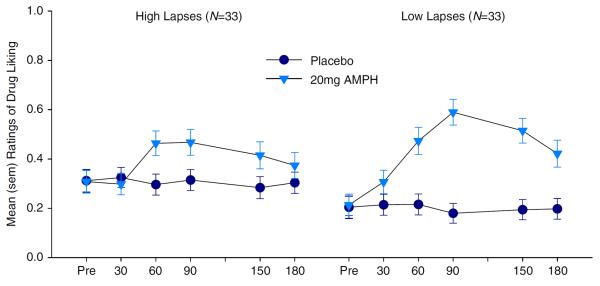

The high attention lapse group reported lower ratings of drug liking after 20 mg d-amphetamine than the low attention lapse group (Fig. 1). This was evidenced by a group × drug dose interaction for liking drug [F(4, 190)=2.77, p<0.05, ], in which simple main effects at each level of drug dose showed a significant group difference at 20 mg d-amphetamine [F(2, 283)=8.85, p<0.001], but not at 10 mg (F<1) or 5 mg (F<1) d-amphetamine, and post hoc tests at 20 mg d-amphetamine confirmed that the high attention lapse group liked the drug less than the low attention lapse group (p<0.05). Groups did not differ on ratings of wanting more drug [F(4, 190)=1.76, p=0.14, ] or feeling the drug [F(4, 190)=1.65, p=0.16, ].

Fig. 1.

Ratings of drug liking for 20 mg d-amphetamine (AMPH) as a function of high vs. low attention lapses

To better characterize the dose by group interaction for drug liking, we also performed simple main effects at each level of group. A significant effect of drug dose was found for low [F(2, 64)=13.80, p<0.001, ] and moderate [F(2, 64)=7.59, p<0.01, ] attention lapse groups, but not the high attention lapse group [F (2, 64)=1.48, p=.24, ]. Both low and moderate (but not high) attention lapse groups liked 20 mg of d-amphetamine more than 5 or 10 mg d-amphetamine. Thus, only the high attention lapse group failed to show increased drug liking at higher drug doses. This finding does not appear to be an artifact of subject grouping, as drug liking in the 20-mg d-amphetamine condition was significantly negatively correlated (partial correlation controlling for order) with attention lapses as a continuous variable [rpartial (96)=−0.32, p<0.01].

Participants tended to show more subjective drug effects at higher doses, with significant drug dose effects for liking the drug [F(2, 190)=3.97, p<0.05, ] and feeling the effects of the drug [F(2, 190)=9.72, p<0.001, ] and a trend for wanting more of the drug [F(2, 190)=2.70, p=0.07, ]. Post hoc tests showed subjects felt the effects of the drug more in the 20-mg d-amphetamine condition than the 10-mg d-amphetamine condition and more in the 10-mg d-amphetamine condition than the 5-mg d-amphetamine condition.

There was also a weak trend for the high attention lapse group to endorse wanting more of the drug less strongly than moderate and low attention lapse groups [F(2, 95)=2.38, p<0.10, ], though post hoc tests showed no significant differences between low, moderate, and high attention lapse groups.

To assess the effect of d-amphetamine on attention lapses among the groups, a 3 (group)×3 (drug dose) mixed design ANCOVA was performed, controlling for placebo attention lapses and drug dose order. Higher drug doses significantly decreased attention lapses (F(2, 186)=4.18, p<0.05, ). Post hoc analyses showed a trend (p< 0.10) for 5 mg d-amphetamine (M=32.80, SD=25.15) to produce longer attention lapses than 10 mg (M=28.30, SD=22.46) or 20 mg (M=26.28, SD=28.00) d-amphetamine. Attention lapses increased slightly in the high attention lapse group and decreased slightly in the moderate and low attention lapse groups as the dose of d-amphetamine increased; however, neither the main effect of group nor the group × drug dose interaction approached significance (F<1). Thus, despite differences in subjective response to d-amphetamine, there were no clear behavioral differences as a function of group.

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between lapses of attention and self-reported ratings of single acute doses of d-amphetamine (5, 10, and 20 mg) in healthy young adults. We hypothesized that subjects who exhibited more lapses of attention would like the drug less, be less interested in receiving more of the drug, and feel the effects of the drug less than subjects with fewer attention lapses. Consistent with this, we found that the group with more attention lapses liked d-amphetamine (20 mg) less than the low attention lapse group. Also, there was a trend for subjects in the high attention lapse group to be less desirous of receiving more of the drug. The groups did not significantly differ in how much they felt the effects of the drug.

As hypothesized, we found that subjects in the high attention lapse group liked d-amphetamine less than subjects in the low attention lapse group, although this was only true at the highest level of d-amphetamine used in the study (20 mg). This is consistent with our earlier work showing that individuals who were more impulsive on a measure of behavioral inhibition (go-no-go) task also experienced less euphoria from 20 mg d-amphetamine (de Wit et al. 2000). One interpretation of this finding is that individuals high on behavioral inattention are less sensitive to the rewarding effects of d-amphetamine. It is also possible that these individuals did not “like” the drug effect because they were highly sensitive to d-amphetamine and found the 20 mg too high. However, the robust drug liking scores after the 20-mg dose across all three groups did not support this interpretation. The lack of relationship between lapses and drug liking after 5 or 10 mg d-amphetamine is probably because neither the 5- nor 10-mg dose produced appreciable levels of liking or euphoria.

In addition to liking the drug less, the high attention lapse group also tended to “want more” of the drug less than the other groups. The direction of this trend is consistent with what might be expected if less attentive individuals are less sensitive to the rewarding effects of d-amphetamine. However, the relationship was weaker than the relationship between attention lapses and drug liking at 20 mg d-amphetamine. It is possible that “wanting” a drug is a less specific measure of positive drug effects and open to alternative interpretations by the participants. For example, individuals might report “wanting” more of a drug because they like its effects, or because they did not notice any strong effect, or because they are simply curious to see what would happen if they took more of the drug. This would likely result in greater variability of responding within groups, which is what we found; the standard deviations were higher for the “want more drug” item than for either of the other two DEQ items.

The high attention lapse group “wanted more drug” in the placebo condition more strongly than the moderate lapses group and to a lesser (nonsignificant) extent more than the low lapses group. This group difference in subjective response to placebo was not hypothesized and may reflect ambiguity in the ratings of wanting more drug, especially in comparisons across groups of individuals. The ratings of wanting more drug may have been influenced by the context of study, in which subjects expected to receive an active drug, and indeed because of the counterbalanced orders, most subjects received the placebo after receiving at least one d-amphetamine dose at a previous visit. Thus, the ratings may have been influenced by expectancies. It is also possible that subjects in the high attention lapse group reported wanting more because they wanted a “higher dose” of the agent administered in order to feel any effect. This would be consistent with observations that higher levels of impulsivity are associated with more positive attitudes toward and greater use of illicit drugs (de Wit 2009). Thus, the group differences in ratings of “want more drug” in the placebo condition must be interpreted with caution because of possible ambiguity in the question. Notably, however, the three groups did not differ on overall ratings of how much they felt the drug effect, suggesting that the high and low lapses groups did not differ in overall sensitivity to the drug but rather in how much they liked or wanted it. It will be of interest to explore more broadly the range of measures on which behaviorally defined groups such as these differ in their responses to d-amphetamine and other drugs.

One of the limitations of this study was the moderate sample size. On subject ratings of wanting more of the drug and feeling the drug's effects after the 20-mg dose, the high attention lapse group was lower than both the moderate and low attention lapse groups. However, the mean differences between high and low attention lapse groups were small to moderate (Cohens d=0.24–0.37). Effects of this magnitude would benefit from an even larger sample to increase power to detect small effects. However, it is noteworthy that the item which most directly assessed the euphoric effects of d-amphetamine, “How much do you like the drug”, produced the strongest group difference at 20 mg d-amphetamine.

It is tempting to speculate about the mechanisms underlying these findings. Generally speaking, one mechanism that might account for higher inattention and lower d-amphetamine induced euphoria is a dysregulation of the dopaminergic system (Baler and Volkow 2006; Blum et al. 2000; Everitt et al. 2008). Stimulant drugs and other compounds that increase dopamine levels reduce symptoms of impulsiveness and inattention in adolescents with ADHD (Rosa-Neto et al. 2005), healthy volunteers (de Wit et al. 2002), and laboratory animals (van Gaalen et al. 2006; Wade et al. 2000), and conversely in animal models, dopamine antagonists increase measures of impulsiveness (van Gaalen et al. 2006; Wade et al. 2000). Thus, these findings suggest that dopamine is involved in inattentive and potentially impulsive behaviors. There is also a large body of evidence linking amphetamine-induced reward and reward salience to dopamine function (Koob and Bloom 1988; Leyton et al. 2007). Specifically, imaging studies suggest that stimulant-induced dopamine release is positively correlated to the level of subjective positive drug effects (Munro et al. 2006; Oswald et al. 2005). Notably, there is also recent evidence that self-reported impulsivity is negatively related to striatal dopamine release induced by amphetamine in humans (Oswald et al. 2007). This is consistent with the findings reported here of a negative association between lapses in attention and amphetamine-induced positive states. Reduced striatal dopamine release specifically to an anticipated reward has also been found in impulsive and inattentive (ADHD) adolescents (Scheres et al. 2007). Thus, deficits in dopamine function may contribute to impulsive and inattentive behaviors, reward hyposensitivity, and blunted subjective response to a dopamine agonist in certain individuals.

We recognize that it is unlikely that the relationship between behavioral indices of inattention and reward sensitivity to stimulants is fully explained by low dopamine release. Impulsiveness and inattention are also associated with other neurotransmitters, such as serotonin (Walderhaug et al. 2002) and norepinephrine (Ventura et al. 2003), as well as with a multitude of organismic and environmental factors such as stress (Iacono et al. 2008; Oswald et al. 2007). These factors may moderate the association between inattentive behaviors, dopamine release, and stimulus-induced euphoria. Nevertheless, although the specific mechanisms for this association remain unknown, both our current and previous (de Wit et al. 2000) findings suggest that behavioral inhibition and lapses of attention (de Wit 2009) are associated with decreased euphoric effects from stimulants.

This is one of the first studies to examine the relationship between behavioral inattention and self-reported drug liking in response to the dopamine agonist d-amphetamine. Strengths of the study include use of a homogenous well-defined sample, the use of a novel behavioral measure of inattention, and the examination of drug effects at multiple drug levels. However, there are also a several aspects of the study that limit our ability to generalize results. The study used a single behavioral measure of inattention, whose association with other measures of impulsivity is not fully understood. It will be important to examine the relationship between amphetamine-induced euphoria and more conventional measures of both inattention and impulsive behavior in future studies. Also, the study used 20 mg as the highest level of d-amphetamine, and higher doses of d-amphetamine may be needed to study deficits in reward sensitivity in relation to cognitive function. Finally, future studies will be needed to identify the role of dopamine and other neurotransmitter systems in these behaviors.

Despite the limitations, these results suggest new prospects for research on the relationship between measures of cognitive function and the subjective experience of reward in response to d-amphetamine. The findings suggest that subjects who are less attentive on a behavioral task find 20 mg of d-amphetamine less rewarding than subjects who are more attentive. This supports the idea that inattention may be related to insensitivity to reward.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Margo Meverden and Adam Strohm for their technical contributions.

This study was supported in part by the National Institute of Drug Abuse grants DA02812, DA09133, and DA021336.

References

- APA . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th edn American Psychiatric Association; Washington, D.C: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arns M, de Ridder S, Strehl U, Breteler M, Coenen A. Efficacy of neurofeedback treatment in ADHD: the effects on inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity: a meta-analysis. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2009;40:180–189. doi: 10.1177/155005940904000311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baler RD, Volkow ND. Drug addiction: the neurobiology of disrupted self-control. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:559–566. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belin D, Mar AC, Dalley JW, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. High impulsivity predicts the switch to compulsive cocaine-taking. Science. 2008;320:1352–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.1158136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum K, Braverman ER, Holder JM, Lubar JF, Monastra VJ, Miller D, et al. Reward deficiency syndrome: a biogenetic model for the diagnosis and treatment of impulsive, addictive, and compulsive behaviors. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32(Suppl: i–iv):1–112. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10736099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos FX, Tannock R. Neuroscience of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the search for endophenotypes. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:617–628. doi: 10.1038/nrn896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos FX, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Milham MP, Tannock R. Characterizing cognition in ADHD: beyond executive dysfunction. Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK. Forty years of methylphenidate treatment in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Atten Disord. 2002;6(Suppl 1):S17–S30. doi: 10.1177/070674370200601s04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H. Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: a review of underlying processes. Addict Biol. 2009;14:22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Phan KL. Positive reinforcement theories of drug use. In: Kassel JD, editor. Substance abuse and emotion. American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wade TR, de Wit H, Richards JB. Effects of dopaminergic drugs on delayed reward as a measure of impulsive behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;150:90–101. doi: 10.1007/s002130000402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Richards JB. Dual determinants of drug abuse: reward and impulsivity. In: Bevins RA, Bardo MT, editors. Nebraska symposium on motivation. University of Nebraska Press; Nebraska: 2004. pp. 19–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Pierri J, Johanson CE. Reinforcing and subjective effects of diazepam in nondrug-abusing volunteers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1989;33:205–213. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Crean J, Richards JB. Effects of d-amphetamine and ethanol on a measure of behavioral inhibition in humans. Behav Neurosci. 2000;114:830–837. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.4.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Enggasser JL, Richards JB. Acute administration of d-amphetamine decreases impulsivity in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:813–825. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Belin D, Economidou D, Pelloux Y, Dalley JW, Robbins TW. Review. Neural mechanisms underlying the vulnerability to develop compulsive drug-seeking habits and addiction. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:3125–3135. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambin M, Swiecicka M. Relation between response inhibition and symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity in children. Br J Clin Psychol. 2009;48:425–430. doi: 10.1348/014466509X449765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gevensleben H, Holl B, Albrecht B, Vogel C, Schlamp D, Kratz O, et al. Is neurofeedback an efficacious treatment for ADHD? A randomised controlled clinical trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discipl. 2009;50:780–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girden ER. ANOVA repeated measures. Vol. 84. Sage; Newbury Park: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhill L, Beyer DH, Finkleson J, Shaffer D, Biederman J, Conners CK, et al. Guidelines and algorithms for the use of methylphenidate in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Atten Disord. 2002;6(Suppl 1):S89–S100. doi: 10.1177/070674370200601s11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausknecht KA, Acheson A, Farrar AM, Kieres AK, Shen RY, Richards JB, et al. Prenatal alcohol exposure causes attention deficits in male rats. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119:302–310. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.1.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Malone SM, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of early-onset addiction: common and specific influences. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:325–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Bloom FE. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of drug dependence. Science. 1988;242:715–723. doi: 10.1126/science.2903550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leth-Steensen C, Elbaz Z, Douglas V. Mean response times, variability and skew in the responding of ADHD children: a response time distributional approach. Acta Psychol (Amst) 2000;104:167–190. doi: 10.1016/s0001-6918(00)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyton M, aan het Rot M, Booij L, Baker GB, Young SN, Benkelfat C. Mood-elevating effects of d-amphetamine and incentive salience: the effect of acute dopamine precursor depletion. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2007;32:129–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lott DC, Kim SJ, Cook EH, Jr, de Wit H. Dopamine transporter gene associated with diminished subjective response to amphetamine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:602–609. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair D, Lorr M, Droppleman L. Manual for the profile of mood states (manual) Educational and Industrial Service; San Diego: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Munro CA, McCaul ME, Oswald LM, Wong DF, Zhou Y, Brasic J, et al. Striatal dopamine release and family history of alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1143–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald LM, Wong DF, McCaul M, Zhou Y, Kuwabara H, Choi L, et al. Relationships among ventral striatal dopamine release, cortisol secretion, and subjective responses to amphetamine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:821–832. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald LM, Wong DF, Zhou Y, Kumar A, Brasic J, Alexander M, et al. Impulsivity and chronic stress are associated with amphetamine-induced striatal dopamine release. Neuroimage. 2007;36:153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Curtin JJ, Tellegen A. Development and validation of a brief form of the multidimensional personality questionnaire. Psychol Assess. 2002;14:150–163. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51:768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JL, Nelson SE, Carroll ME. Impulsive choice as a predictor of acquisition of IV cocaine self- administration and reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in male and female rats. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;16:165–177. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulos CX, Parker JL, Le DA. Increased impulsivity after injected alcohol predicts later alcohol consumption in rats: evidence for “loss-of-control drinking” and marked individual differences. Behav Neurosci. 1998;112:1247–1257. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.5.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves DL, Bleiberg J, Roebuck-Spencer T, Cernich AN, Schwab K, Ivins B, et al. Reference values for performance on the automated neuropsychological assessment metrics V3.0 in an active duty military sample. Mil Med. 2006;171:982–994. doi: 10.7205/milmed.171.10.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, Ortengren A, Richards JB, de Wit H. Dimensions of impulsive behavior: personality and behavioral measures. Pers Individ Differ. 2006;40:305–315. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa-Neto P, Lou HC, Cumming P, Pryds O, Karrebaek H, Lunding J, et al. Methylphenidate-evoked changes in striatal dopamine correlate with inattention and impulsivity in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuroimage. 2005;25:868–876. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres A, Milham MP, Knutson B, Castellanos FX. Ventral striatal hyporesponsiveness during reward anticipation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:720–724. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmonds DJ, Fotedar SG, Suskauer SJ, Pekar JJ, Denckla MB, Mostofsky SH. Functional brain correlates of response time variability in children. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:2147–2157. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TJ, Wilens TE, Biederman J, Weisler RH, Read SC, Pratt R. Efficacy and safety of mixed amphetamine salts extended release (Adderall XR) in the management of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in adolescent patients: a 4-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Clin Ther. 2006;28:266–279. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer SV, Hawk LW, Jr, Richards JB, Shiels K, Pelham WE, Jr, Waxmonsky JG. Stimulant treatment reduces lapses in attention among children with ADHD: the effects of methylphenidate on intra-individual response time distributions. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2009;37:805–816. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9316-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Mezzich A, Cornelius JR, Pajer K, Vanyukov M, et al. Neurobehavioral disinhibition in childhood predicts early age at onset of substance use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1078–1085. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gaalen MM, van Koten R, Schoffelmeer AN, Vanderschuren LJ. Critical involvement of dopaminergic neurotransmission in impulsive decision making. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura R, Cabib S, Alcaro A, Orsini C, Puglisi-Allegra S. Norepinephrine in the prefrontal cortex is critical for amphetamine-induced reward and mesoaccumbens dopamine release. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1879–1885. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01879.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walderhaug E, Lunde H, Nordvik JE, Landro NI, Refsum H, Magnusson A. Lowering of serotonin by rapid tryptophan depletion increases impulsiveness in normal individuals. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;164:385–391. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1238-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TL, Justice AJ, de Wit H. Differential subjective effects of D-amphetamine by gender, hormone levels and menstrual cycle phase. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;73:729–741. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00818-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]