Abstract

The development of new approaches to the construction of fluorine-containing target molecules is important for a variety of scientific disciplines, including medicinal chemistry. In this Article, we describe a method for the catalytic enantioselective synthesis of tertiary alkyl fluorides through Negishi reactions of racemic α-halo-α-fluoroketones, which represents the first catalytic asymmetric cross-coupling that employs geminal dihalides as electrophiles. Thus, selective reaction of a C–Br (or C–Cl) bond in the presence of a C–F bond can be achieved with the aid of a nickel/bis(oxazoline) catalyst. The products of the stereoconvergent cross-couplings, enantioenriched tertiary α-fluoroketones, can be converted into an array of interesting organofluorine compounds.

Introduction

Motivated by potential applications in biomedical research and other disciplines,1 substantial effort has been dedicated to the development of methods for the preparation of organofluorine compounds.2 In the case of alkyl fluorides, advances have been described in the catalytic enantioselective synthesis of stereogenic centers that bear a fluorine substituent,3 particularly α to a carbonyl group. Although most studies have addressed the generation of secondary stereocenters,4 a few reports have examined the establishment of tertiary centers; currently, the latter methods are largely limited to either cyclic or doubly activated acyclic α-fluorocarbonyl compounds.5,6 To the best of our knowledge, no general catalytic enantioselective process has been discovered for the synthesis of simple tertiary α-fluorinated acyclic ketones.7−9

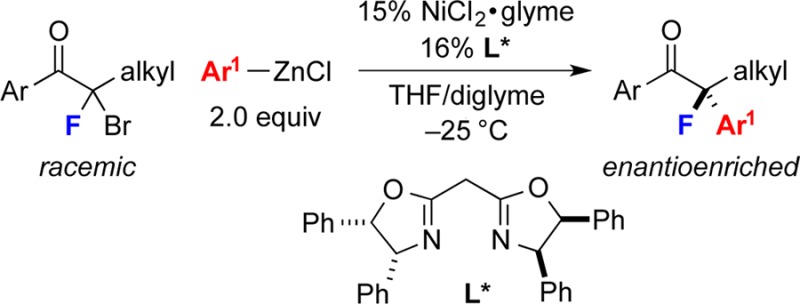

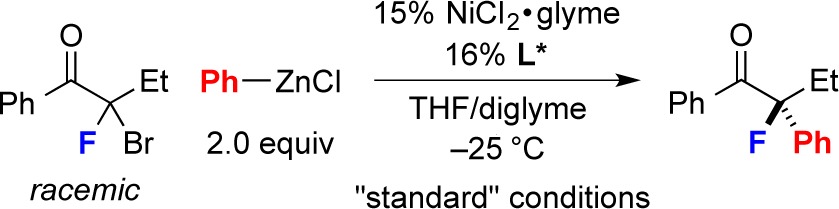

During the past decade, we have developed an array of nickel-catalyzed asymmetric cross-coupling methods, employing racemic alkyl electrophiles as reaction partners; to date, all of the electrophiles have been secondary, with Z = H (eq 1).10,11 We have now begun to explore enantioselective couplings of other families of electrophiles, beginning with geminal dihalides (eq 1; Z = F, X = halide);12 such H → F substitutions can have a dramatic impact on reactivity and/or ee.13 If a suitable catalyst could achieve selective cleavage of the C–X bond, along with efficient and highly enantioselective C–C bond formation, then this would enable the catalytic asymmetric synthesis of tertiary alkyl fluorides.

|

1 |

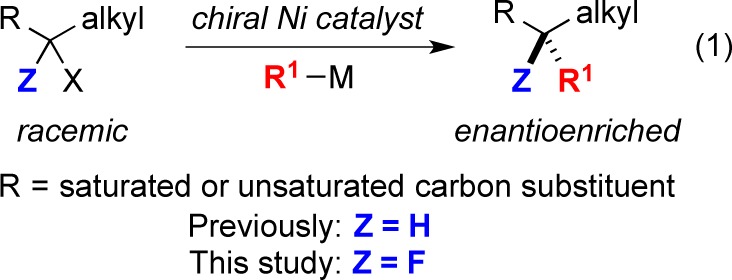

In view of the high interest in the enantioselective synthesis of α-fluorocarbonyl compounds,4,5,8,9 as well as the excellent functional-group compatibility of Negishi reactions,14 we chose to examine the coupling of α-halo-α-fluoroketones with organozinc reagents. In this Article, we describe the first catalytic asymmetric cross-coupling that employs geminal dihalides as electrophiles, specifically, a nickel/bis(oxazoline)-catalyzed stereoconvergent Negishi arylation of racemic α-bromo-α-fluoroketones to generate tertiary α-fluorinated acyclic ketones (eq 2).

|

2 |

Results and Discussion

At the time that we began our investigation in 2011, we were not aware of any precedent for selective nickel-catalyzed cross-couplings of α-halo-α-fluoro compounds. However, during the course of our studies, Ando reported diastereoselective Kumada reactions of α-bromo-α-fluoro-β-lactams with aryl Grignard reagents,15 employing a NiCl2·glyme/bis(oxazoline) catalyst that we had described for enantioselective couplings of aryl Grignard reagents with α-bromoketones.10c

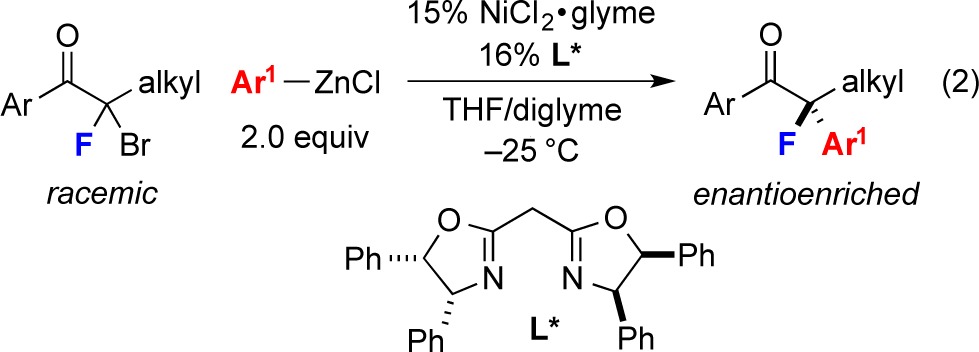

Unfortunately, our attempts to apply our previous methods for Kumada10c and Negishi10d arylations to the cross-coupling of the racemic α-bromo-α-fluoroketone illustrated in Table 1 were unsuccessful (<2% yield). However, through the appropriate choice of reaction parameters, we were able to achieve the desired α-arylation and to generate the tertiary alkyl fluoride with very good enantioselectivity (97% ee; Table 1, entry 1). NiCl2·glyme and bis(oxazoline) L* are commercially available and air-stable.

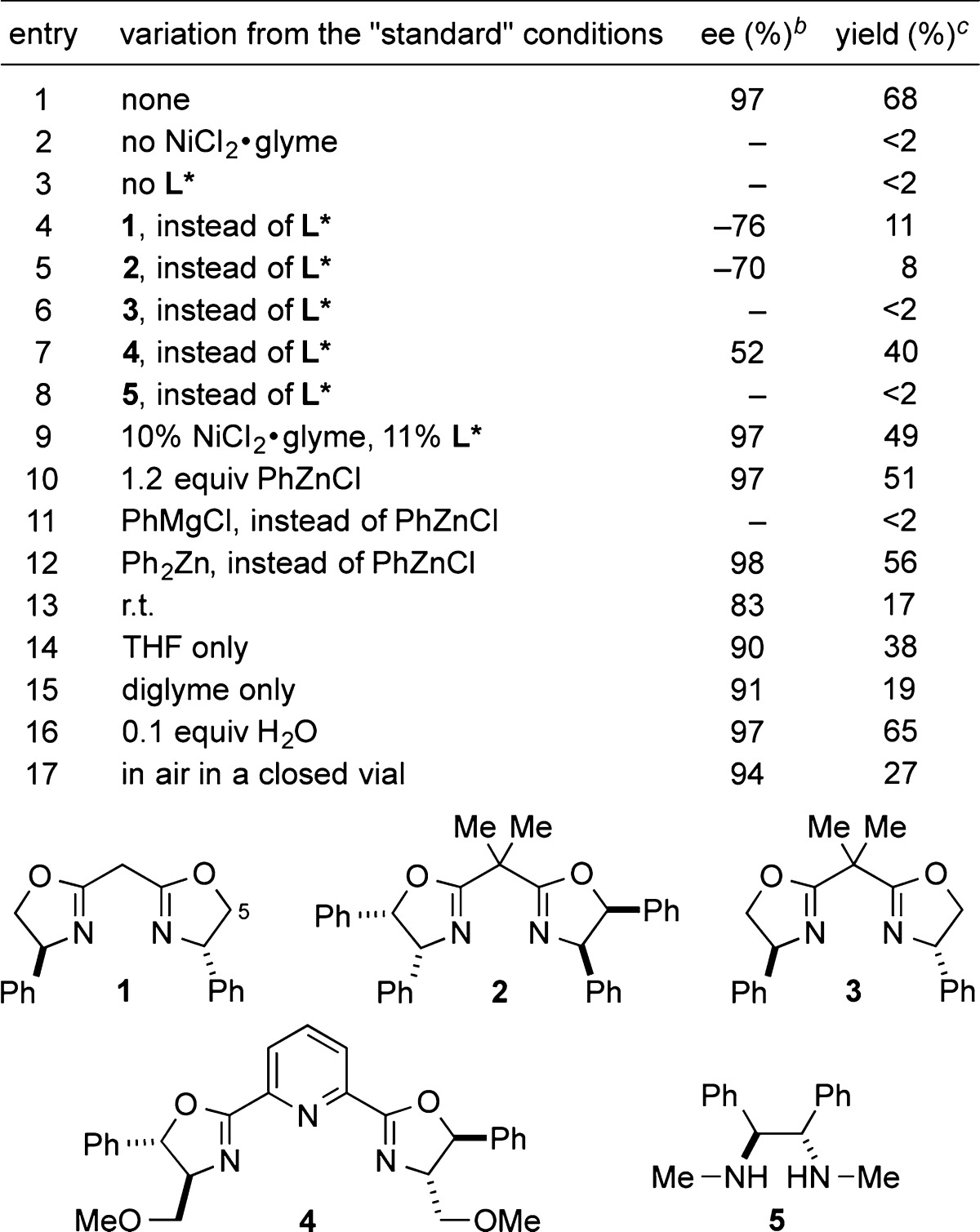

Table 1. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of Tertiary Alkyl Fluorides: Effect of Reaction Parametersa.

All data are the average of two experiments.

A negative ee value signifies that the major product of the reaction is the opposite (R) enantiomer.

The yields were determined through analysis by 19F NMR spectroscopy, with the aid of an internal standard.

Table 1 provides information on the impact of various reaction parameters on the efficiency of this catalytic asymmetric synthesis of tertiary alkyl fluorides. In the absence of NiCl2·glyme or of ligand L*, essentially no carbon–carbon bond formation is observed (entries 2 and 3). The cis phenyl substituent in the 5 position of the oxazolines plays an important role in enantioselectivity and yield (entry 4), as does the substitution on the one-carbon linker that bridges the oxazolines (entries 5 and 6). A variety of pybox and 1,2-diamine ligands10b,10d,10e furnish inferior results (e.g., entries 7 and 8). The use of less catalyst or less nucleophile leads to a modest decrease in yield, although no erosion in ee (entries 9 and 10). Under our optimized conditions, PhMgCl is not a useful coupling partner (entry 11), whereas good enantioselectivity but less-efficient cross-coupling is observed when Ph2Zn serves as the nucleophile (entry 12). Conducting the Negishi reaction at room temperature or with a single solvent causes a small drop in ee and a substantial loss in yield (entries 13–15). The presence of water (0.1 equiv) has essentially no impact on the course of the reaction (entry 16), whereas running the reaction under air results in decreased yield (entry 17).

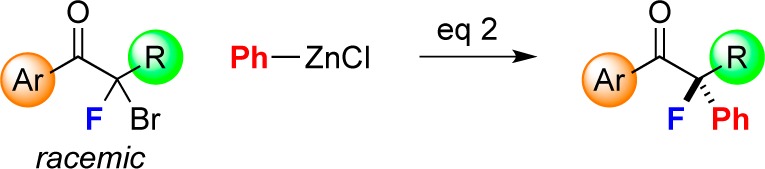

Our optimized conditions can be applied to the catalytic asymmetric Negishi arylation of a variety of racemic α-bromo-α-fluoroketones, furnishing tertiary alkyl fluorides in generally good ee (Table 2).16 The R group of the ketone can vary in size, although a lower ee is observed with a bulky isopropyl substituent (entries 1–6). High enantioselectivity is typically obtained whether the aromatic group (Ar) is para-, meta-, or ortho-substituted, and whether it is electron-rich or electron-poor (entries 7–16); we have not previously observed high ee in related nickel-catalyzed cross-couplings with ortho-substituted Ar groups (entries 14 and 15; previously: ≤75% ee).10c,10d,17 Functional groups such as an olefin, alkyl chloride,18 aryl methyl ether,19 and aryl fluoride20 are compatible with the reaction conditions.

Table 2. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of Tertiary Alkyl Fluorides: Scope with Respect to the Electrophilea.

All data are the average of two experiments.

Yield of purified product.

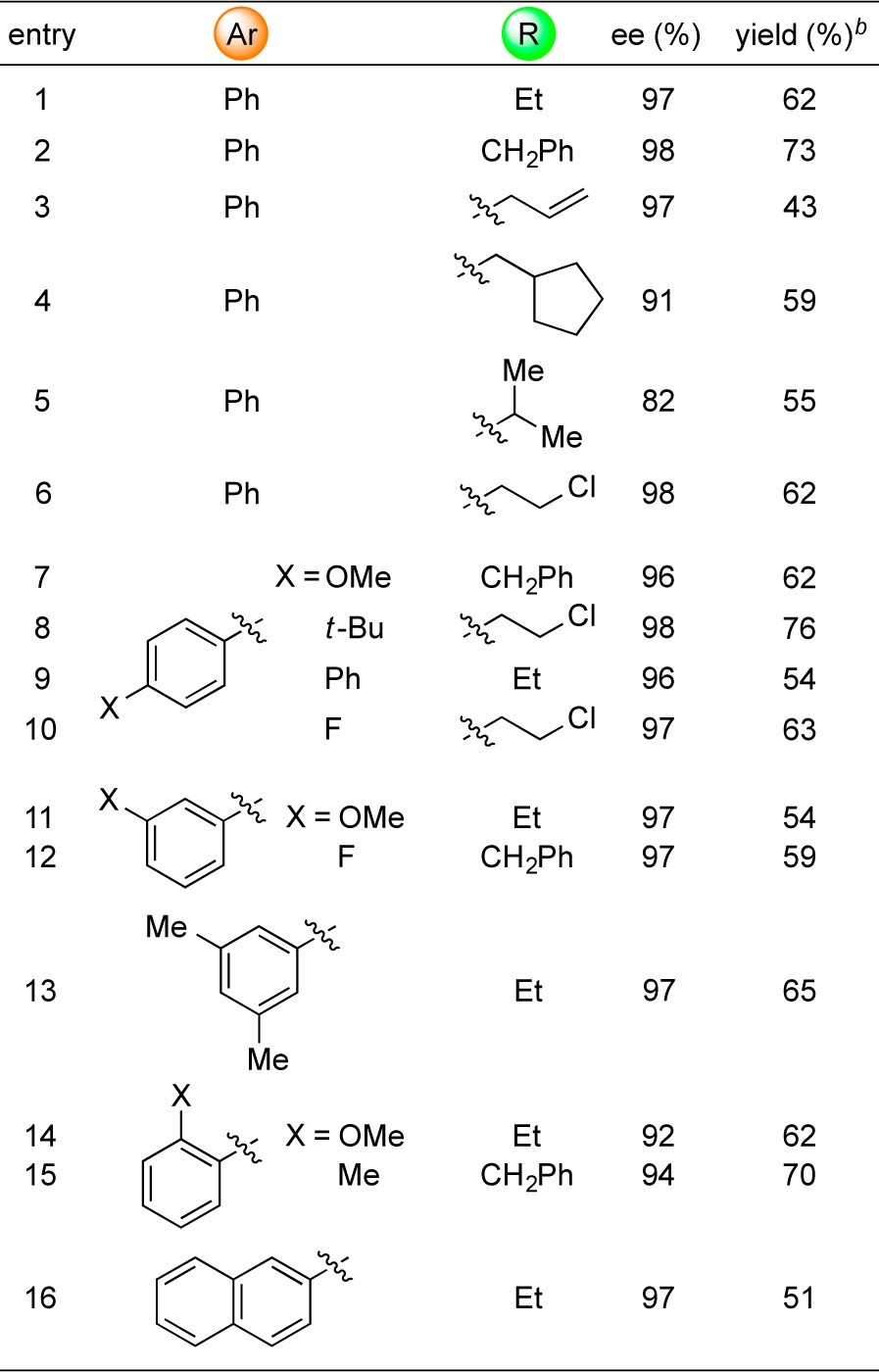

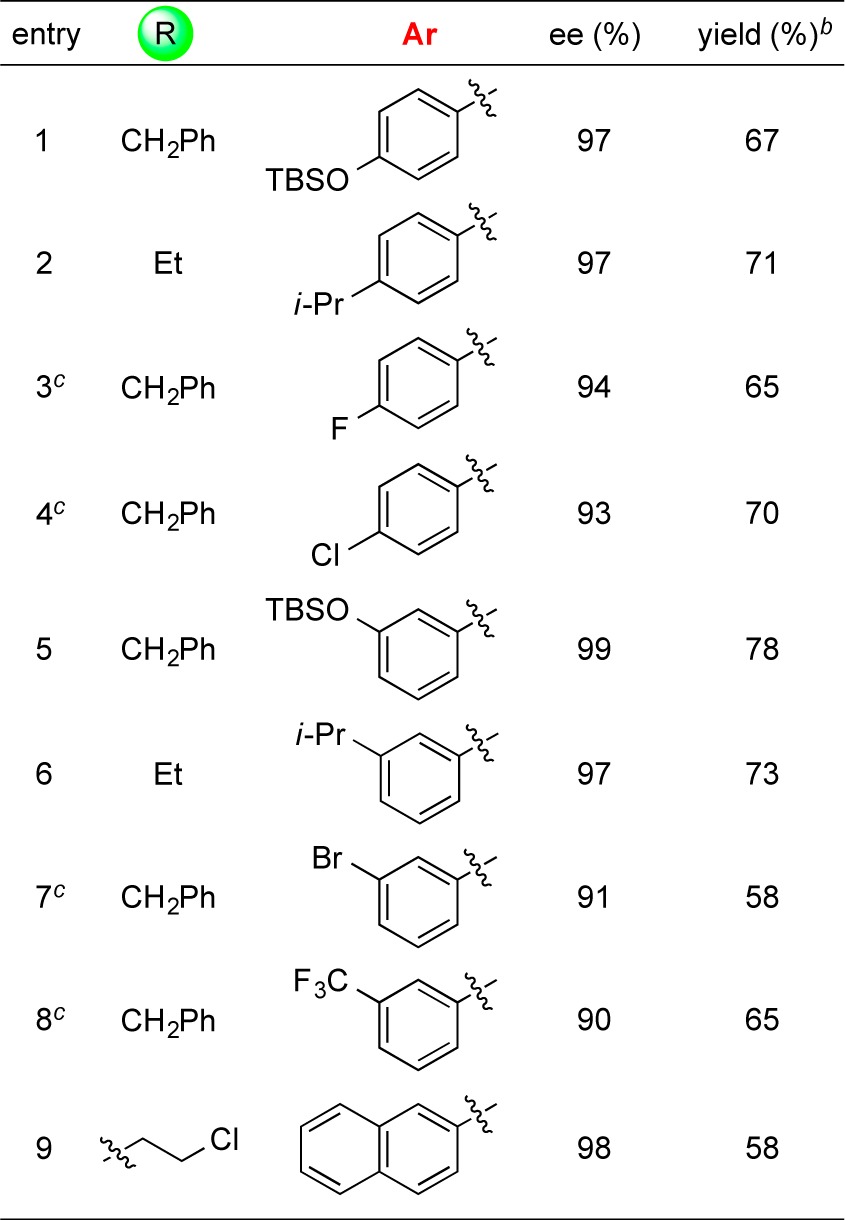

The scope of this method for the catalytic asymmetric synthesis of tertiary alkyl fluorides is also fairly broad with respect to the nucleophile (ArZnCl; Table 3).21 Thus, para- and meta- (but not ortho-)22 substituted arylzinc reagents are suitable cross-coupling partners, furnishing the desired α-fluoroketone in good ee. Electron-rich as well as electron-poor nucleophiles can be employed; in the case of the latter, a reaction temperature of −20 °C, rather than −25 °C, is optimal. A silyl ether, aryl chloride, and aryl bromide23 are compatible with the coupling conditions.

Table 3. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of Tertiary Alkyl Fluorides: Scope with Respect to the Nucleophilea.

All data are the average of two experimens.

Yield of purified product.

Reaction temperature: −20 °C.

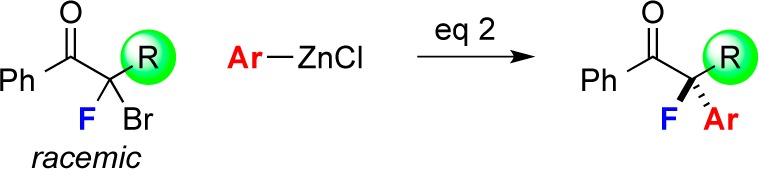

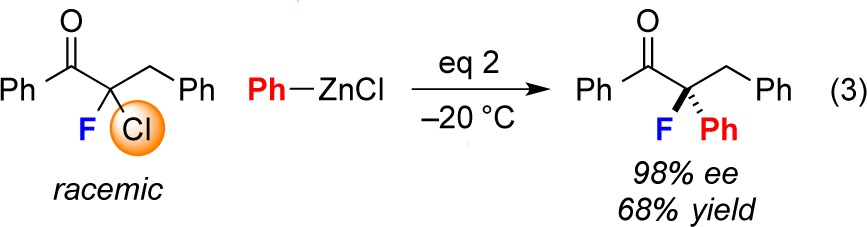

This method for the selective cross-coupling of a geminal dihalide electrophile is not limited to α-bromo-α-fluoroketones. Under similar conditions, a racemic α-chloro-α-fluoroketone also reacts with an arylzinc reagent to generate a tertiary alkyl fluoride in good ee (eq 3). In contrast, in the case of related cross-couplings, α-chlorocarbonyl compounds were not suitable reaction partners.10c−10e

|

3 |

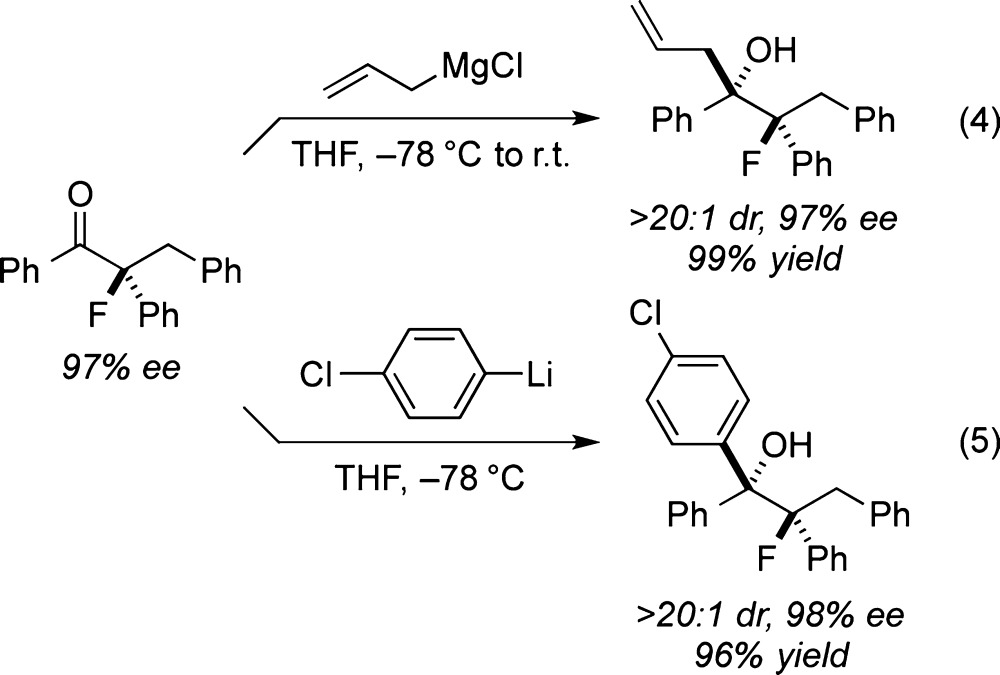

The enantioenriched organofluorine cross-coupling products can be derivatized with high stereoselectivity. For example, nucleophilic additions of allyl and aryl nucleophiles to the carbonyl group proceed with >20:1 dr to generate densely functionalized adducts (eqs 4 and 5).24,25

|

4 |

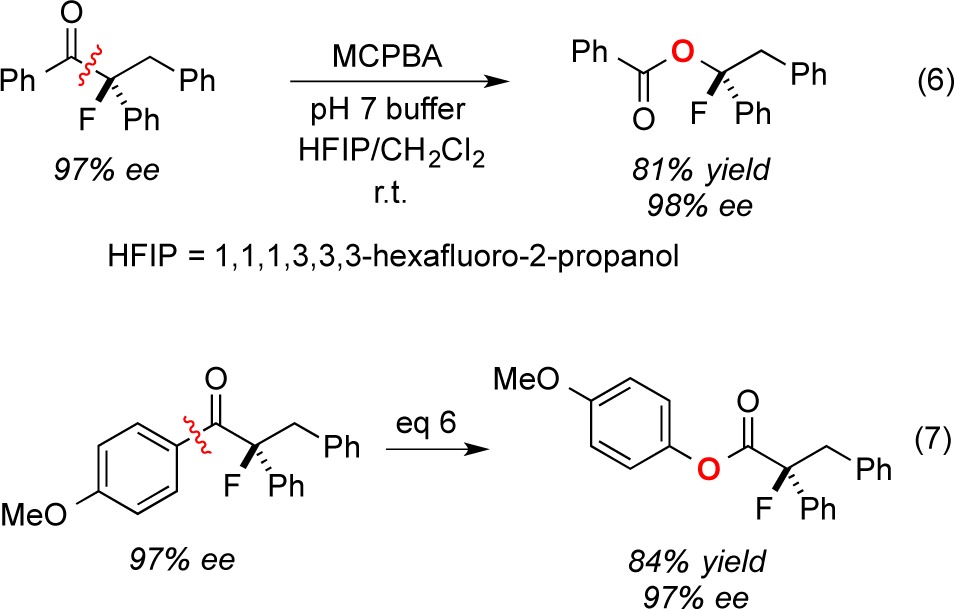

Moreover, regioselective Baeyer–Villiger oxidation of the enantioenriched α-fluoroketones can be achieved, thereby providing access to either an alkyl ester or an aryl ester by controlling the relative migratory aptitudes of the ketone substituents (eqs 6 and 7).26−28 This oxidation thereby enables, to our knowledge, the first asymmetric synthesis of acylated fluorohydrins (eq 6),29 as well as an indirect method for the catalytic enantioselective synthesis of tertiary α-fluoroesters (eq 7) and amides.30

|

6 |

Conclusions

In summary, we have developed the first catalytic asymmetric cross-coupling method that employs geminal dihalides as electrophiles. Specifically, we have established that nickel/bis(oxazoline)-catalyzed stereoconvergent Negishi reactions of racemic α-halo-α-fluoroketones provide access to enantioenriched tertiary alkyl fluorides, thereby complementing earlier catalytic asymmetric methods for the synthesis of organofluorine compounds, which have typically focused on the generation of secondary alkyl fluorides. The α-fluoroketones that are produced in these Negishi couplings can be transformed into a variety of interesting families of organofluorine target molecules. Additional investigations of catalytic enantioselective cross-couplings of alkyl electrophiles are underway.

Acknowledgments

Support has been provided by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of General Medical Sciences: R01-GM62871). We thank Trixia M. Buscagan, Dr. Nathan D. Schley, Dr. Michael K. Takase (X-ray Crystallography Facility; a Bruker KAPPA APEX II X-ray diffractometer was purchased via NSF CRIF:MU award CHE-0639094 to the California Institute of Technology), and Dr. Scott C. Virgil (Caltech Center for Catalysis and Chemical Synthesis, supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation) for assistance.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental procedures and compound characterization data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- For monographs, see:; a Fluorine in Pharmaceutical and Medicinal Chemistry; Gouverneur V., Müller K., Eds.; Imperial College Press: London, 2012. [Google Scholar]; b Fluorine-Related Nanoscience with Energy Applications; Nelson D. J., Brammer C. N., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 2011. [Google Scholar]; c Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry and Chemical Biology; Ojima I., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- For monographs, see:; a Efficient Preparations of Fluorine Compounds; Roesky H. W., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, 2013. [Google Scholar]; b Science of Synthesis; Percy J. M., Ed.; Georg Thieme: Stuttgart, Germany, 2006; Vol. 34. [Google Scholar]

- For reviews, see:; a Gouverneur V.; Lozano O. In Science of Synthesis; De Vries J. G., Molander G. A., Evans P. A., Eds.; Georg Thieme: Stuttgart, Germany, 2011; Vol. 3, pp 851–930. [Google Scholar]; b Valero G.; Companyó X.; Rios R. Chem.—Eur. J. 2011, 17, 2018–2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Cahard D.; Xu X.; Couve-Bonnaire S.; Pannecoucke X. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 558–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Lectard S.; Hamashima Y.; Sodeoka M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 2708–2732. [Google Scholar]; See also:; Liang T.; Neumann C. N.; Ritter T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 8214–8264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For early examples of catalytic, asymmetric α-fluorinations of aldehydes, see:; a Marigo M.; Fielenbach D.; Braunton A.; Kjærsgaard A.; Jørgensen K. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 3703–3706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Steiner D. D.; Mase N.; Barbas C. F. III. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 3706–3710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Beeson T. D.; MacMillan D. W. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 8826–8828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For examples of methods with some generality, see:; a Shibata N.; Kohno J.; Takai K.; Ishimaru T.; Nakamura S.; Toru T.; Kanemasa S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4204–4207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Nakamura M.; Hajra A.; Endo K.; Nakamura E. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 7248–7251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Hamashima Y.; Suzuki T.; Takano H.; Shimura Y.; Sodeoka M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 10164–10165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Bélanger É.; Cantin K.; Messe O.; Tremblay M.; Paquin J.-F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 1034–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Reddy D. S.; Shibata N.; Nagai J.; Nakamura S.; Toru T.; Kanemasa S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Ishimaru T.; Shibata N.; Horikawa T.; Yasuda N.; Nakamura S.; Toru T.; Shiro M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 4157–4161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Wu L.; Falivene L.; Drinkel E.; Grant S.; Linden A.; Cavallo L.; Dorta R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 2870–2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Phipps R. J.; Toste F. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 1268–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For examples of the catalytic asymmetric synthesis of other families of tertiary alkyl fluorides, see:; a Phipps R. J.; Hiramatsu K.; Toste F. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8376–8379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Shunatona H. P.; Früh N.; Wang Y.-M.; Rauniyar V.; Toste F. D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 7724–7727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wu J.; Wang Y.-M.; Drljevic A.; Rauniyar V.; Phipps R. J.; Toste F. D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 13729–13733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For examples of methods for the synthesis of racemic products, see:; a Wang W.; Jasinski J.; Hammond G. B.; Xu B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 7247–7252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Guo Y.; Tao G.-H.; Blumenfeld A.; Shreeve J. M. Organometallics 2010, 29, 1818–1823. [Google Scholar]; c Zhang W.; Hu J. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 2799–2804. [Google Scholar]; d Guo C.; Wang R.-W.; Guo Y.; Qing F.-L. J. Fluorine Chem. 2012, 133, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- For a pioneering study, although with limited scope with regard to the diversity of product structures, see:Shibatomi K.; Futatsugi K.; Kobayashi F.; Iwasa S.; Yamamoto H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 5625–5627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For an example with esters, see:Tengeiji A.; Shiina I. Molecules 2012, 17, 7356–7378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For a few examples and leading references, see:; a Do H.-Q.; Chandrashekar E. R. R.; Fu G. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 16288–16291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wilsily A.; Tramutola F.; Owston N. A.; Fu G. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 5794–5797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Lou S.; Fu G. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1264–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Lundin P. M.; Esquivias J.; Fu G. C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 154–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Dai X.; Strotman N. A.; Fu G. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 3302–3303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For an example of an application in the total synthesis of a natural product (carolacton), see:Schmidt T.; Kirschning A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 1063–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For nonenantioselective nickel-catalyzed cross-couplings of geminal dihalides (double and triple alkylation of CH2Cl2 and CHCl3, respectively), see:; a Csok Z.; Vechorkin O.; Harkins S. B.; Scopelliti R.; Hu X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 8156–8157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Vechorkin O.; Csok Z.; Scopelliti R.; Hu X. Chem.—Eur. J. 2009, 15, 3889–3899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For a recent overview, see:Cahard D.; Bizet V. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 135–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For a review, see:Negishi E.-i.; Hu Q.; Huang Z.; Wang G.; Yin N. In The Chemistry of Organozinc Compounds; Rappoport Z., Marek I., Eds.; Wiley: New York, 2006; Chapter 11. [Google Scholar]

- Tarui A.; Kondo S.; Sato K.; Omote M.; Minami H.; Miwa Y.; Ando A. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 1559–1565. [Google Scholar]

- Under our standard conditions: (a) On a gram-scale, the asymmetric Negishi cross-coupling illustrated in entry 2 of Table 2 furnished the desired tertiary alkyl fluoride in 97% ee and 66% yield (1.41 g of product). (b) Hydrodebromination of the electrophile was a side reaction (the secondary alkyl fluoride was produced in <5% ee). (c) During the course of a cross-coupling, no kinetic resolution of the electrophile was detected (<5% ee), and the ee of the product was constant. (d) The cross-coupling product was stable (no further reaction and no erosion in ee). (e) A cyclic ketone (α-tetralone-derived) and a 2-thienyl ketone were not suitable electrophiles.

- A ketone in which the aromatic group (Ar) was mesityl did not undergo cross-coupling under our standard conditions.

- For an example of a nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling of an unactivated alkyl chloride, see ref (10b).

- For a review of nickel-catalyzed cross-couplings that proceed via cleavage of a C–O bond, see:Rosen B. M.; Quasdorf K. W.; Wilson D. A.; Zhang N.; Resmerita A.-M.; Garg N. K.; Percec V. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 1346–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For a recent report of nickel-catalyzed cross-couplings of aryl fluorides, see:Tobisu M.; Xu T.; Shimasaki T.; Chatani N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 19505–19511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Our standard conditions were not effective for the cross-coupling of a thienylzinc reagent or a Knochel-type arylzinc reagent:Krasovskiy A.; Malakhov V.; Gavryushin A.; Knochel P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 6040–6044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essentially no carbon–carbon bond formation was observed when o-tolylzinc chloride was employed as the nucleophile under our standard conditions.

- Nickel-catalyzed Negishi reactions of aryl halides are well-established; for examples, see:Phapale V. B.; Cárdenas D. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1598–1607Interestingly, under the conditions described in eq 2, essentially no coupling of PhZnCl with an aryl iodide or an aryl bromide was observed (≥95% recovery of 4-bromotoluene and 4-iodotoluene). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The stereochemistry of each product (eqs 4 and 5) has been determined by X-ray crystallography (see the Supporting Information). Reduction of the ketone with NaBH4 also proceeded with high diastereoselectivity (>20:1) and in good yield (>99%). However, we have not yet been able to establish the relative stereochemistry of the major diastereomer.

- For a review of the effect of a fluorine substituent on the conformation of molecules, see:Hunter L.Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2010, 6, No. 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For the Baeyer–Villiger reactions illustrated in eqs 6 and 7, the selectivity is ≥20:1 for the indicated bond cleavage.

- For a discussion of the effect of a fluorine substituent on migratory aptitude in Baeyer–Villiger reactions, see:; a Crudden C. M.; Chen A. C.; Calhoun L. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 2851–2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Grein F.; Chen A. C.; Edwards D.; Crudden C. M. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 861–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S.; Tanaka H.; Amii H.; Uneyama K. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 1547–1552. [Google Scholar]

- For examples of applications of this family of compounds, see:; a Rye C. S.; Baell J. B.; Street I. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 3306–3311. [Google Scholar]; b Demoute J. P.; Hoemberger G.; Pazenok S.; Babin D. 5-Halo-4-fluoro-4,7,7-trimethyl-3-oxabicyclo[4.1.0]heptane-2-ones, Method for Their Production and Their Use in the Production of Cyclopropane Carboxylic Acids. WO 2001034592 A1, May 17, 2001.; c Ishibashi M. Method for Screening Therapeutic Agent for Glomerular Disorder. U.S. Patent 20090041719 A1, Feb. 12, 2009.

- The aryl ester (eq 7) can readily be converted into an amide by treatment with an amine (e.g., pyrrolidine: 70% isolated yield). We are not aware of reports of direct methods for the catalytic enantioselective synthesis of tertiary α-fluorinated acyclic amides.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.