Abstract

An azobenzene-containing surfactant was synthesized for the phase transfer of α-cyclodextrin (α-CD)-capped gold nanoparticles between water and toluene phases by host–guest chemistry. With the use of the photoisomerization of azobenzene, the reversible phase transfer of gold nanoparticles was realized by irradiation with UV and visible light. Furthermore, the phase transfer scheme was applied for the quenching of a reaction catalyzed by gold nanoparticles, as well as the recovery and recycling of the gold nanoparticles from aqueous solutions. This work will have significant impact on materials transfer and recovery in catalysis and biotechnological applications.

Keywords: azobenzene, cyclodextrin, host−guest systems, phase transfer, photoresponsive systems

Because of their unique optical, electrical, and chemical properties, nanoparticles (NPs) have attracted considerable interest in diverse research areas, including catalysis, sensing, electronics, biomedicine, and optics.1−5 The rapid growth in applications of NPs has been accompanied by the development of synthetic methods resulting in NPs with well-defined properties, such as shape, size, composition and surface modification.6−10 However, many of these synthetic strategies are realized with the aid of specific hydrophobic or hydrophilic ligands in their respective organic or aqueous solvents, while synthesized NPs possess distinct solubility in media with different polarities. Therefore, additional steps for phase transfer are usually required, especially between water and organic solvents, for specific applications.11,12 To date, such strategies involve either changing the wettability of the surface ligands or changing the properties of the solvent. However, reversible phase transfer of NPs between two immiscible phases still remains challenging and complicated. Most previous approaches required sequential addition of different ligands or drastic physicochemical changes to the solvent, such as temperature and pH.13−16 Moreover, none of the reported reversible phase transfer strategies has been used for practical applications.

The use of light as an external stimulus for stimuli-responsive systems is of particular interest since light can be delivered remotely, precisely in space and time, and quantitatively. Smart materials based on photoresponsive systems have emerged as a dynamic research area, where the properties of matter can be reversibly modulated with light.17−19 For example, light-switchable α-cyclodextrin (α-CD) and azobenzene interaction has been employed to control the viscosity of hydrogels,20,21 the release of cargos from carriers,22,23 and the assembly of macroscopic/microscopic objects.24,25

In this report, the photoswitchable host–guest interaction between α-CD and azobenzene is used as a trigger to induce the reversible phase transfer of the AuNPs between water and toluene. Furthermore, the phase transfer scheme was applied for the quenching of a reaction catalyzed by gold nanoparticles, as well as the recovery and recycling of the gold nanoparticles. Indeed, the design of recyclable nanoparticle-based catalysts has been a major area in green chemistry, where strategies including magnetic separation and gravitational sedimentation are involved.26,27 However, the implementation of such recovery and recycling methods has caused separation and reuse problems limiting the application with homogeneous catalysts.28 For example, magnetic separation requires magnetic ingredients in the nanoparticles which may be hard to achieve or may result in low catalytic activity. In contrast, we envision that our system of light-responsive recycling of nanoparticles will promote the development of recyclable catalysts with high efficiency.

Results and Discussion

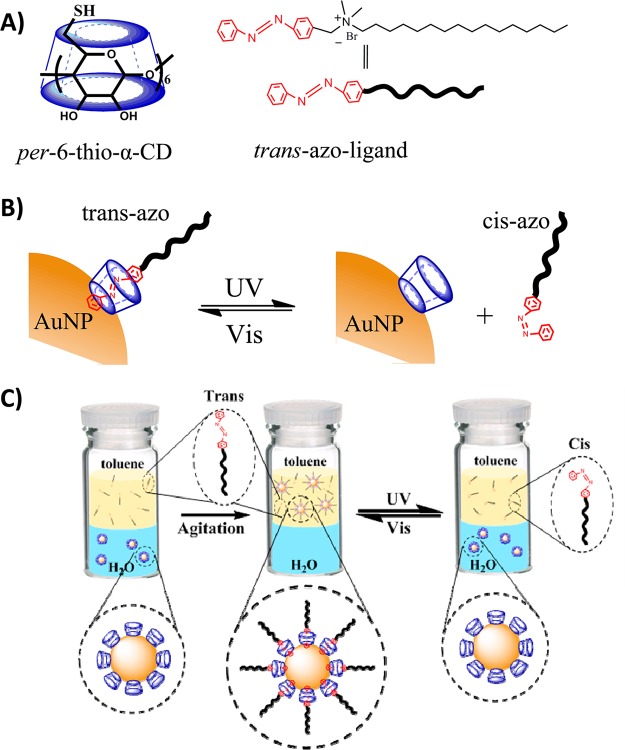

The present photoreversible supramolecular system consists of an azobenzene-containing surfactant (azo-ligand) and a thiolated α-CD (Figure 1A). The key innovation of this approach is the light-induced reversible modification of the azo-ligand on the AuNP surface coated with thiolated α-CD (Figure 1B). Azobenzenes represent a class of photoresponsive compounds that undergo reversible trans-to-cis isomerization by the irradiation of UV and visible light. While the trans isomer can form a stable inclusion complex with α-CD by matching size and hydrophobic interactions, the cis isomer cannot. As shown in Figure 1C, the α-CD-coated AuNPs are initially dispersed in water as a consequence of the secondary hydroxyl groups of α-CD,29 while the trans-azo-ligands are dissolved in toluene. After agitation, the trans-azo-ligands bind to the α-CDs on the AuNP surface, which brings the hydrophobic alkyl chains to the periphery of the AuNP to form a reverse micelle-like structure. In this way, the AuNPs are converted from hydrophilic to hydrophobic and are transferred from water to toluene. Upon UV irradiation, the azo-ligand isomerizes from the trans to the cis state, and the cis-azo-ligand dissociates from the AuNP surface. As a result, the AuNP surface recovers its hydrophilic property, and the AuNPs are transferred back into water from toluene. Importantly, the toluene-to-water transfer process can be reversed when the cis-azo-ligands are converted to the trans state by irradiation with visible light. As illustrated in the proposed scheme, the excellent reversibility of azobenzene isomerization allows the phase transfer of AuNPs between water and toluene to be performed reversibly for multiple cycles by alternating UV/vis irradiation.

Figure 1.

(A) Structures of host per-6-thio-α-CD and guest azobenzene-containing ligand (azo-ligand). (B) Photoreversible inclusion of azo-ligand in α-CD-coated AuNPs. (C) Light-responsive phase transfer of α-CD-capped AuNPs by azo-ligands between the water and toluene phases.

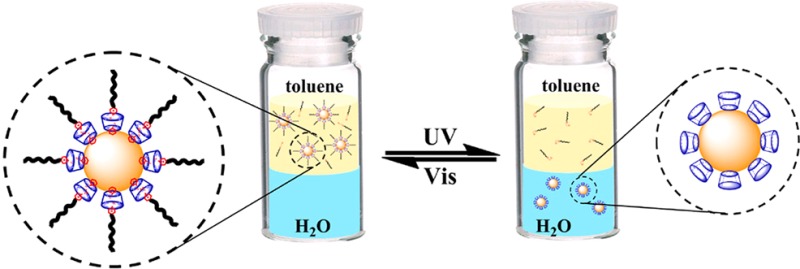

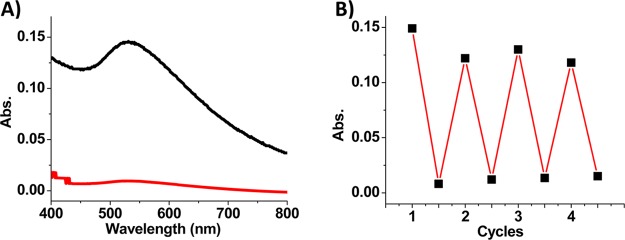

In our work, the per-6-thio-α-cyclodextrin and α-CD-coated AuNPs were prepared following the methods reported previously.29,30 As described in Figure 2A, the UV/vis spectra of the resulting water-soluble AuNPs dispersed in aqueous solution show an absorption peak at 516 nm. The average particle size was estimated as 3.6 ± 0.5 nm using TEM. The azobenzene-containing surfactant was synthesized using the method described in the Supporting Information. The design of the azo-ligand was inspired by a ferrocene derivative described by Liu et al. The positively charged nitrogen atoms of the azobenzene surfactant transfer water molecules and counterions to the vicinity of AuNPs, a process which assists in the formation of the interfacial azobenzene-CD inclusion complexes.29 As expected, the azobenzene part of the surfactant ligand dissolved in toluene can be photoisomerized by UV/vis irradiation. As shown in Figure S1, the absorption spectra of the azo-ligand synthesized in the trans state show a characteristic peak at 326 nm. Upon UV light irradiation at 365 nm, the intensity of this peak decreases dramatically, indicating photoisomerization of the azo-ligand from the trans to the cis state (Figure S1). When visible light is applied afterward, the peak intensity at 326 nm recovers as the azo-ligand undergoes cis-to-trans isomerization (Figure S2). The photoisomerization of the azo-ligand is totally reversible by monitoring the peak intensity at 326 nm upon alternating UV and visible light irradiation for multiple cycles (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Absorption spectrum of thiolated α-CD-coated AuNPs (3.6 nm) in water. (B) Reversible photoisomerization of azo-ligand (absorbance at 326 nm) in toluene upon alternating irradiation with UV and visible light.

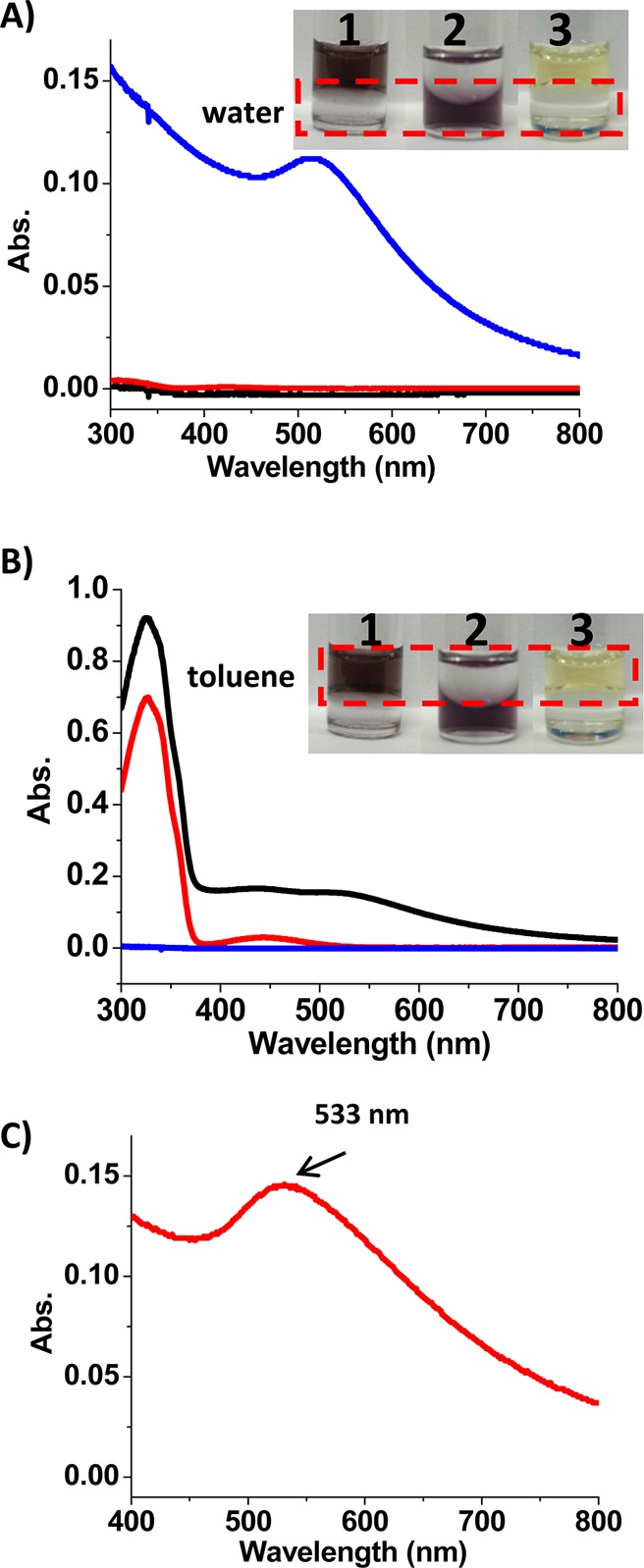

It has been reported that the host–guest interaction at the nanoparticle-solution interface can be used for reversible phase transfer of nanoparticles in aqueous/organic mixtures.15,29 Therefore, we first demonstrated that our new trans-azo-ligand could also function as a phase transfer agent for the α-CD-coated AuNPs. Initially, the α-CD-coated AuNPs were dispersed in water (deep brown), while the azo-ligands were dissolved in toluene (yellow). Upon mixing the two phases, the α-CD-coated AuNPs were transferred from water (bottom layer) to toluene (top layer), as indicated by the color change of the two phases (vial 1, inset of Figure 3A,B). The deep brown aqueous AuNP solution turned colorless, while the light yellow toluene phase became colored. However, in the absence of azo-ligands in the toluene phase, all the AuNPs stayed in the water phase (vial 2, Figure 3A,B).

Figure 3.

Phase transfer of AuNPs from water to toluene phase by trans-azo-ligands (vial 1). Vial 2 has no azo-ligands in the toluene phase, and vial 3 has no AuNPs in the water phase. The absorption spectra show absorbance of (A) water phase and (B) toluene phase in vial 1 (black), vial 2 (blue) and vial 3 (red). (C) Absorption spectrum of AuNPs in the toluene phase is achieved by subtraction of the red line from the black line in panel B.

The phase transfer of AuNPs was also characterized by the absorption spectra of the water and toluene phases. Figure 3A shows the absorption spectra of AuNPs in water before (blue curve) and after phase transfer (black curve). Figure 3B shows the absorption spectra of the toluene phase. Before phase transfer (red curve, Figure 3B), only the absorption band of trans-azo-ligands was observed with no absorption at wavelengths longer than 500 nm. After phase transfer (black curve, Figure 3B), a spectrum showing the absorption of both the trans-azo-ligands and the AuNPs was achieved. Subtraction of the spectrum of the toluene phase before phase transfer from the spectrum after phase transfer resulted in a characteristic spectrum of AuNPs in toluene with a peak at 533 nm (Figure 3C). Due to the phase transfer, a certain degree of aggregation was observed, shown by the shoulder peak at around 600 nm (Figure 3C). And the color of AuNPs in toluene is the result of both dispersed and aggregated AuNPs.

We also studied the phase transfer of AuNPs as a function of the concentrations of trans-azo-ligand by maintaining a constant initial concentration (0.1 mg/mL) of AuNPs in aqueous solution. As measured by absorbance at 533 nm, the concentration of nanoparticles transferred to the toluene phase was found to increase in proportion to the initial concentration of the azo-ligand in the toluene phase (Figure S3). Thus, when the concentration of azo-ligand reached 0.4 mM, a complete phase transfer of AuNPs was achieved, as illustrated by the plateau in Figure S3.

We found a remarkable difference between trans- and cis-azo-ligand in the water-to-toluene phase transfer of α-CD-coated AuNPs. More specifically, trans-azo-ligand could form an inclusion complex with the α-CD-coated AuNPs, resulting in the water-to-toluene phase transfer of AuNPs, but the cis-azo-ligand could not. To reach isomerization equilibrium before phase transfer of AuNPs, the trans-azo-ligand was dissolved in toluene and irradiated by UV light at 365 nm for 1 h. As shown in Figure S4, the spectrum of AuNPs transferred to the toluene phase, which was achieved by subtraction in the same way as that in Figure 3C, shows only a small peak at 533 nm. We attributed the limited amount of transferred AuNPs to the residual trans-azo-ligands after UV light irradiation.

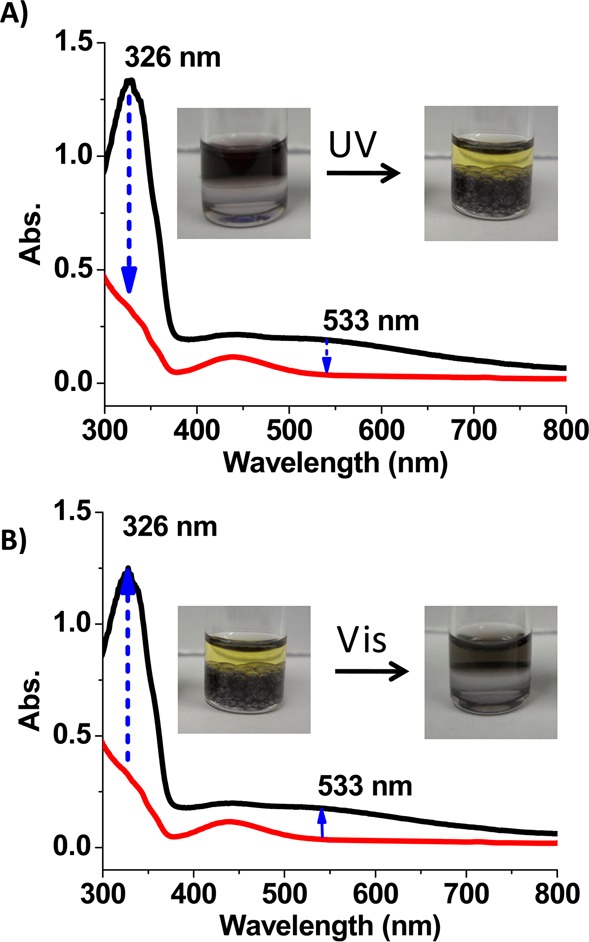

The results above suggest that the formation of interfacial inclusion complexes and the phase transfer of AuNPs can be manipulated by UV/vis light irradiation via the photoisomerization of azobenzene moieties. As shown by the pictures in Figure 4A, after AuNPs were transferred to the toluene phase by the trans-azo-ligand, UV light irradiation caused the AuNPs in the toluene phase (upper layer) to move back to the water phase (lower layer). UV light-responsive phase transfer was also demonstrated by the absorption measurements of the toluene phase (Figure 4A). Upon irradiation by UV light, the absorption of trans-azo-ligand at 326 nm decreased dramatically, which is indicative of the trans-to-cis isomerization of the azo-ligand. Concomitantly, the absorption of AuNPs at 533 nm in toluene disappears. Phase transfer of AuNPs to the water phase depends on the duration of UV irradiation and is complete after about 1 h (Figure S5).

Figure 4.

Absorption spectra of toluene phase during the light-responsive phase transfer of AuNPs. (A) Phase transfer of α-CD-coated AuNPs from toluene to water phase by irradiation with UV light. (B) Phase transfer of α-CD-coated AuNPs from water to toluene phase by irradiation with visible light.

After phase transfer of AuNPs from toluene to water by UV light irradiation, visible light was applied in order to reverse the transfer. As shown in Figure 4B, after irradiation by visible light, the AuNPs were again transferred to the toluene phase. Absorption at both 326 and 533 nm then increased as a result of the visible light-triggered cis-to-trans isomerization of the azo-ligand and the concomitant phase transfer of AuNPs, respectively. This process is also time-dependent, and all the AuNPs were transferred to toluene after 30 min of visible light irradiation (Figure S6).

The azo-ligand-mediated phase transfer of the α-CD-coated AuNPs is light-responsive. On the basis of the reversible isomerization of azo-ligand, the phase transfer of AuNPs is also reversible. In a typical experiment, the irradiation of UV and visible light was continued for 60 and 30 min, respectively, in each cycle. By monitoring the absorbance at 533 nm, which is attributable to the AuNPs in the toluene phase, the reversible phase transfer of AuNPs was observed as a result of the alternating UV and visible light irradiation over multiple cycles (Figure 5). It was also found that the absorbance of AuNPs in the toluene phase decreased after the light-triggered reversible phase transfer. We attributed the decreased absorbance to the formation of aggregated structures of AuNPs. However, most of the AuNPs remained in a dispersed state in both water and toluene phases during the reversible phase transfer, as shown in TEM images (Figure S7).

Figure 5.

(A) Absorption spectra of toluene phase upon irradiation with UV (red) and visible (black) light during reversible phase transfer. (B) Reversible phase transfer of AuNPs (absorbance at 533 nm in toluene phase) between water and toluene phase.

Metallic nanoparticles, such as gold and platinum NPs, have shown great promise in the fabrication of novel catalysts with excellent performance and versatility. Phase transfer is one of the most important techniques in the applications of functional nanoparticles. To demonstrate the applications of the phase transfer system, we applied the host–guest chemistry-based transfer strategy for the control of catalytic reactions. It has been reported that CD-capped-AuNPs can catalyze the reduction of 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) to 4-aminophenol (4-AP) in the presence of sodium borohydride (NaBH4) in aqueous solution.31−35 Using this reaction as a model system, we first examined the catalytic ability of the synthesized thiolated α-CD-capped AuNPs by monitoring the UV/vis absorption. The addition of AuNPs to the solution containing 4-NP and NaBH4 caused the fading and ultimate disappearance of the 400 nm peak (Figure S8), revealing the conversion of 4-NP to 4-AP.

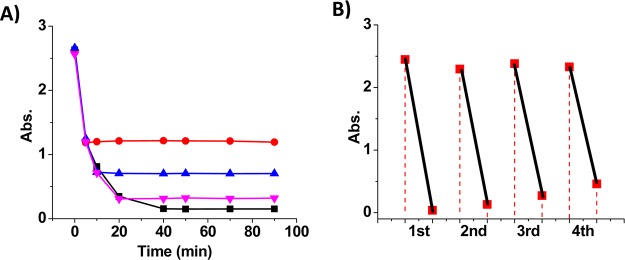

Since the trans-azo-ligand could transfer the α-CD-capped AuNPs from water to toluene, it seemed feasible to use this strategy to quench the catalytic reaction at will via removal of the catalytic AuNPs. As shown in Figure 6A, the reduction of 4-NP to 4-AP was interrupted immediately upon the addition of the trans-azo-ligand dissolved in toluene. However, without the trans-azo-ligand, the reaction proceeded to completion.

Figure 6.

(A) Absorbance (400 nm in water) during the reduction of 4-NP (0.3 mM) in the presence of NaBH4 (15 mM) and α-CD-capped AuNPs (6.7 μg/mL): reaction not quenched (black) and quenched by phase transfer of AuNPs from the addition of toluene containing azo-ligands at 5 min (red), 10 min (blue), and 20 min (pink). (B) Multicycle reduction of 4-NP (absorbance at 400 nm) catalyzed by AuNPs recovered and recycled through photoreversible phase transfer.

Moreover, we applied the photoreversible phase transfer for the recovery and recycling of catalytic α-CD-capped AuNPs to enhance their lifetime for both economic and environmental benefits. In a typical experiment (see Supporting Information and Figure S9), after the completion of 4-NP reduction in the first cycle, the AuNPs were recovered and transferred to the toluene phase by trans-azo-ligand. The water phase with product was replaced by fresh water. Upon irradiation of UV light, the AuNPs were transferred back to water by the trans-to-cis isomerization of the azo-ligand. The second cycle of reaction was performed after the addition of 4-NP and NaBH4. The AuNPs were then recovered and transferred to toluene upon irradiation of visible light which triggered the cis-to-trans isomerization of the azo-ligand. Thus, by the alternating irradiation of UV and visible light, the same batch of AuNPs can be recycled to catalyze multiple rounds of 4-NP reduction. As shown in Figure 6B, the absorption of 4-NP at 400 nm decreases dramatically in each cycle of the reaction, indicating the sustained catalytic activity of the AuNPs during the light-regulated recovery and recycling process.

Conclusions

In summary, we have demonstrated photoreversible phase transfer of AuNPs by the photoswitchable host–guest interaction between α-CD and azobenzene. The basic principle relies on the reversible surface modification of the α-CD-capped hydrophilic AuNPs with an azobenzene-containing surfactant ligand. Reversible phase transfer can be performed for multiple cycles as monitored by absorption spectra. By the alternating irradiation of UV and visible light, the same batch of α-CD-capped hydrophilic AuNPs can be recycled to catalyze multiple rounds of 4-NP reduction. Using the phase transfer strategy based on the host–guest interaction, we were able to quench the catalytic reaction by removal of the catalytic AuNPs. Furthermore, by alternating UV and visible irradiation, recovery and recycling of catalytic AuNPs could be realized. The method of reversible phase transfer based on photoswitchable molecular recognition could bring more insight to nanoparticle surface engineering, thus improving and augmenting applications in different research areas.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis of per-6-Iodo-α-cyclodextrin (2)

To a mixture of triphenylphosphine (21 g) and I2 (20.2 g) in DMF (40 mL) was added α-CD (1) (4.3 g). The mixture was stirred at 80 °C under an atmosphere of N2. After 18 h, the solution was concentrated to half volume under reduced pressure. The pH was then adjusted to 9–10 by adding sodium methoxide in methanol (3 M, 30 mL) with cooling. The solution was stirred at room temperature for 1 h, and methanol was added to form a precipitate. The precipitate was collected by filtration and allowed to air-dry to yield per-6-iodo-α-cyclodextrin as a white powder. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Mercury 300 at 300 MHz. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 3.30 (t, J = 9 Hz, 6H), δ 3.8–3.55 (m, 12H), δ 3.55–3.71 (m, 12H), δ 3.83 (bd, J = 9 Hz, 6H), δ 4.96 (d, J = 3 Hz, 6H), δ 5.60 (d, J = 2 Hz, 6H), δ 5.81 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 6H).

Synthesis of per-6-Thio-α-cyclodextrin (3)

Per-6-iodo-α-cyclodextrin (0.965 g) was dissolved in DMF (10 mL), and thiourea (0.301 g) was added. The reaction mixture was heated to 70 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere. After 19 h, the DMF was removed under reduced pressure to give a yellow oil, which was dissolved in water (50 mL). Sodium hydroxide (0.26 g) was added, and the reaction mixture was heated to a gentle reflux under a nitrogen atmosphere. After 1 h, the resulting suspension was acidified with aqueous KHSO4, and the precipitate was collected by filtration, washed thoroughly with water, and dried. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 2.16 (t, J = 6 Hz, 6H), δ 2.79 (m, 6H), δ 3.14 (br d, J = 14 Hz, 6H), δ 3.25–3.41 (m, 12H), δ 3.72–3.82 (m, 12H), δ 4.89 (t, J = 2.5 Hz, 6H), δ 5.58 (s, 6H), δ 5.73 (d, J = 6 Hz, 6H).

Synthesis of α-Cyclodextrin-Capped Gold Nanoparticles

A 50 mg sample of HAuCl4 was dissolved in 20 mL DMSO. This solution was quickly mixed with another 20 mL of DMSO containing 75.5 mg of NaBH4 and 10.5 mg of per-6-thio-α-cyclodextrin. The reaction mixture turned deep brown immediately, but the reaction was allowed to continue for 24 h. At this point, 40 mL of CH3CN was added to precipitate the colloid, which was collected by centrifugation, washed with 60 mL of CH3CN: DMSO (1: 1 v/v) and 60 mL of ethanol, isolated by centrifugation, and dried under vacuum (60 °C) for 24 h.

The number of CDs per AuNP can be calculated using the surface areas of CD and AuNPs. Each CD (∼15 Å) occupies an area of ∼180 Å2. The surface area of the gold nanoparticle (3.6 nm) is ∼4000 Å2 and the surface coverage by CD is about 80%. Therefore, the average particle is covered by ∼18 covalently attached α-CD hosts.

Synthesis of 4-Methylazobenzene (4)

Three grams (27.8 mmol) of p-toluidine and 3 g of (27.8 mmol) of nitrosobenzene were dissolved in 50 mL of glacial acetic acid, and the mixture was stirred under a nitrogen atmosphere for 24 h at room temperature. After removal of acetic acid under reduced pressure, the resulting solid was recrystallized from ethanol–water, followed by purification by column chromatography. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 2.42 (s, 3H), δ 7.39–7.44 (m, 2H), δ 7.52–7.63 (m, 3H), δ 7.79–7.87 (m, 2H), δ 7.87–7.92 (m, 2H).

Synthesis of 4-(Bromomethyl)azobenzene (5)

The 4-methylazobenzene (2.5 g) was dissolved in 54 mL of CCl4 followed by the addition of 2.28 g of N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) and 0.043 g of benzoyl peroxide (BPO). The mixture was refluxed for 24 h under a nitrogen atmosphere. The resulting solution was filtrated while hot, followed by the removal of solvent. The solid product was purified by column chromatography. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 4.58 (s, 2H), δ 7.41–7.65 (m, 5H), δ 7.79–7.98 (m, 4H).

Synthesis of (Dimethylaminomethyl)azobenzene (6)

Dimethylamine dissolved in THF (10 mL, 2 M) was added to a solution of 4-(bromomethyl)azobenzene (2.23 g, 8 mmol) in dichloromethane (DCM) at 0 °C. The mixture was allowed to reach room temperature and was stirred overnight. Solvents were removed, and NaOH (15 mL, 4 M aqueous) was added. The mixture was extracted with hexane (3 × 80 mL). The aqueous layer was made strongly basic by adding solid sodium hydroxide, and the resulting solution was extracted with diethyl ether (3 × 80 mL). The combined organic layer was dried over magnesium sulfate and filtered. Solvents were removed, yielding the product as yellow oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 2.26 (s, 6H), δ 3.59 (s, 2H), δ 7.40–7.71 (m, 5H), δ 7.71–7.89 (m, 4H). ESI-MS: m/z 240.15 [M + H]+ (calc. for [C15H17N3+H] + 240.32).

Synthesis of Azo-ligand (7)

(Dimethylaminomethyl)azobenzene (4 mmol) in dry ethanol (25 mL) was mixed with an equimolar amount of 1-bromohexadecane (5 mmol), and the mixture was refluxed for 24 h. Solvent was evaporated, and the crude azo-ligand compound was purified by column chromatography. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 0.86 (t, 3H), δ 1.24 (bs, 26H), δ 1.81 (m, 2H), δ 2.81 (s, 6H), δ 3.57 (m, 2H), δ 4.28 (s, 2H), δ 7.45–7.60 (m, 5H), δ 7.67–7.79 (m, 4H). ESI-MS: m/z 464.40 [M]+ (calc. for [C31H50N3]+ 464.75).

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by grants awarded by the National Institutes of Health (GM079359 and CA133086), by the National Key Scientific Program of China (2011CB911000), NSFC grants (NSFC 21221003 and NSFC 21327009) and China National Instrumentation Program 2011YQ03012412.

Supporting Information Available

Synthesis of azobenzene-containing surfactant; absorption spectra of the trans-azo-ligand and of the cis-azo-ligand; absorbance of AuNPs transferred to toluene phase containing variable concentrations of azo-ligand; absorption spectrum of AuNPs transferred to the toluene phase by cis-azo-ligand. AuNPs with absorbance at 533 nm in toluene phase transferred to water phase from toluene phase upon irradiation with UV light at different times; AuNPs with absorbance at 533 nm in toluene phase transferred to toluene phase from water phase upon irradiation with visible light at different times; TEM images of AuNPs during reversible phase transfer; reduction of 4-NP in the presence of NaBH4 and α-CD-capped AuNPs and conversion of 4-NP to 4-AP monitored by absorption measurement. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Welch C. M.; Compton R. G. The Use of Nanoparticles in Electroanalysis: A Review. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006, 384, 601–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner I.; Baron R.; Willner B. Integrated Nanoparticle-Biomolecule Systems for Biosensing and Bioelectronics. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2007, 22, 1841–1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber W.; Ford G. Propagation of Optical Excitations by Dipolar Interactions in Metal Nanoparticle Chains. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 70, 125429. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken J. D. III; Finke R. G. A Review of Modern Transition-Metal Nanoclusters: Their Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications in Catalysis. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 1999, 145, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson N. A.; Lian T. Ultrafast Electron Transfer at the Molecule-Semiconductor Nanoparticle Interface. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2005, 56, 491–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzelczak M.; Pérez-Juste J.; Mulvaney P.; Liz-Marzán L. M. Shape Control in Gold Nanoparticle Synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 1783–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shchukin D. G.; Sukhorukov G. B. Nanoparticle Synthesis in Engineered Organic Nanoscale Reactors. Adv. Mater. 2004, 16, 671–682. [Google Scholar]

- Sun S.; Zeng H. Size-Controlled Synthesis of Magnetite Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 8204–8205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz E.; Willner I. Integrated Nanoparticle-Biomolecule Hybrid Systems: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 6042–6108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sau T. K.; Murphy C. J. Room Temperature, High-Yield Synthesis of Multiple Shapes of Gold Nanoparticles in Aqueous Solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 8648–8649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubertret B.; Skourides P.; Norris D. J.; Noireaux V.; Brivanlou A. H.; Libchaber A. In Vivo Imaging of Quantum Dots Encapsulated in Phospholipid Micelles. Science 2002, 298, 1759–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.; Öçsoy I.; Yuan Q.; Wang R.; You M.; Zhao Z.; Song E.; Zhang X.; Tan W. One-Step Facile Surface Engineering of Hydrophobic Nanocrystals with Designer Molecular Recognition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 13164–13167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards E. W.; Chanana M.; Wang D.; Möhwald H. Stimuli-Responsive Reversible Transport of Nanoparticles across Water/Oil Interfaces. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 320–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin B.; Zhao Z.; Song R.; Shanbhag S.; Tang Z. A Temperature-Driven Reversible Phase Transfer of 2-(Diethylamino) Ethanethiol-Stabilized CdTe Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 9875–9878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorokhin D.; Tomczak N.; Han M.; Reinhoudt D. N.; Velders A. H.; Vancso G. J. Reversible Phase Transfer of (CdSe/ZnS) Quantum Dots between Organic and Aqueous Solutions. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 661–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imura Y.; Morita C.; Endo H.; Kondo T.; Kawai T. Reversible Phase Transfer and Fractionation of Au Nanoparticles by pH Change. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 9206–9208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager K. G.; Barrett C. J. Novel Photo-Switching Using Azobenzene Functional Materials. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A. 2006, 182, 250–261. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett C. J.; Mamiya J.; Yager K. G.; Ikeda T. Photo-Mechanical Effects in Azobenzene-Containing Soft Materials. Soft Matter 2007, 3, 1249–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ercole F.; Davis T. P.; Evans R. A. Photo-Responsive Systems and Biomaterials: Photochromic Polymers, Light-Triggered Self-Assembly, Surface Modification, Fluorescence Modulation and Beyond. Polym. Chem. 2010, 1, 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Tomatsu I.; Hashidzume A.; Harada A. Contrast Viscosity Changes upon Photoirradiation for Mixtures of Poly(acrylic acid)-Based α-Cyclodextrin and Azobenzene Polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 2226–2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamesue S.; Takashima Y.; Yamaguchi H.; Shinkai S.; Harada A. Photoswitchable Supramolecular Hydrogels Formed by Cyclodextrins and Azobenzene Polymers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 7461–7464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalluri S. K. M.; Voskuhl J.; Bultema J. B.; Boekema E. J.; Ravoo B. J. Light-Responsive Capture and Release of DNA in a Ternary Supramolecular Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 9747–9751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao W.; Chen W.; Xu X.; Li C.; Zhang J.; Zhuo R.; Zhang X. Design of a Cellular-Uptake-Shielding “Plug and Play” Template for Photo Controllable Drug Release. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 3526–3530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalluri S. K. M.; Ravoo B. J. Light-Responsive Molecular Recognition and Adhesion of Vesicles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 5371–5374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H.; Kobayashi Y.; Kobayashi R.; Takashima Y.; Hashidzume A.; Harada A. Photoswitchable Gel Assembly Based on Molecular Recognition. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon B.; Wai C. M. Microemulsion-Templated Synthesis of Carbon Nanotube-Supported Pd and Rh Nanoparticles for Catalytic Applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 17174–17175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann S.; Schätz A.; Grass R. N.; Stark W. J.; Reiser O. A Recyclable Nanoparticle-Supported Palladium Catalyst for the Hydroxycarbonylation of Aryl Halides in Water. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 1867–1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole-Hamilton D. J. Homogeneous Catalysis-New Approaches to Catalyst Separation, Recovery, and Recycling. Science 2003, 299, 1702–1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Alvarez J.; Ong W.; Román E.; Kaifer A. E. Phase Transfer of Hydrophilic, Cyclodextrin-Modified Gold Nanoparticles to Chloroform Solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 11148–11154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Ong W.; Román E.; Lynn M. J.; Kaifer A. E. Cyclodextrin-Modified Gold Nanospheres. Langmuir 2000, 16, 3000–3002. [Google Scholar]

- Huang T.; Meng F.; Qi L. Facile Synthesis and One-Dimensional Assembly of Cyclodextrin-Capped Gold Nanoparticles and Their Applications in Catalysis and Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 13636–13642. [Google Scholar]

- Gadelle A.; Defaye J. Selective Halogenation at Primary Positions of Cyclomaltooligosaccharides and a Synthesis of Per-3,6-anhydro Cyclomaltooligosaccharides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1991, 30, 78–80. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Jiang M. Reversible Aggregation of Gold Nanoparticles Driven by Inclusion Complexation. J. Mater. Chem. 2007, 17, 4249–4254. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar G. S.; Savariar C.; Saffran M.; Neckers D. Chelating Copolymers Containing Photosensitive Functionalities. 3. Photochromism of Cross-Linked Polymers. Macromolecules 1985, 18, 1525–1530. [Google Scholar]

- Sperotto E.; van Klink G. P. M.; De Vries J. G.; van Koten G. C–N Coupling of Nitrogen Nucleophiles with Aryl And Heteroaryl Bromides Using Aminoarenethiolato–Copper (I) (Pre-)Catalyst. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 3478–3484. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.