Abstract

Purpose

Current treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is not adequate for most elderly patients. This is the first part of an ongoing study of AML and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and evaluated the efficacy and toxicity of sapacitabine, a novel oral cytosine nucleoside analog, in previously untreated or first relapsed elderly patients with AML.

Patients and Methods

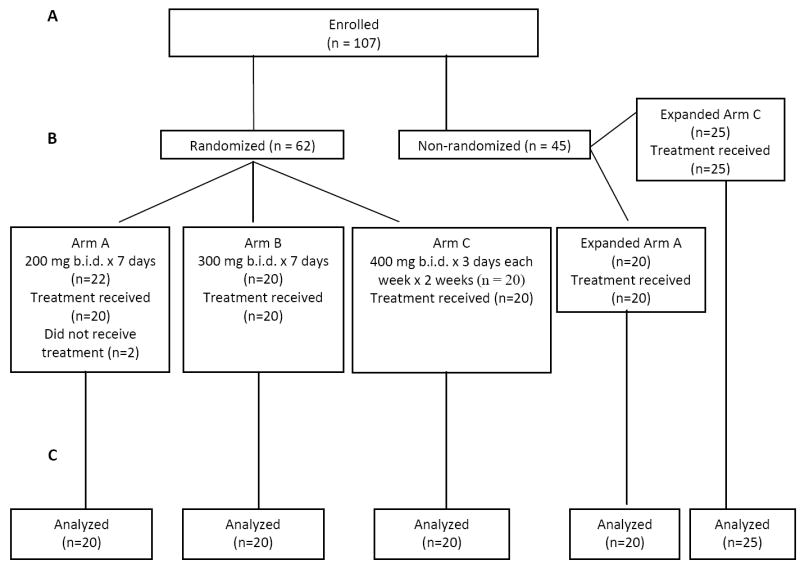

Patients aged 70 years or older with adequate performance status were randomized to receive one of the three schedules of oral sapacitabine: A) 200 mg twice daily x 7 days; B) 300 mg twice daily x 7 days; C) 400 mg twice daily x 3 days, then weekly x 2 weeks. Randomization is stratified by previously untreated vs. previously treated for AML. The intent-to treatment population includes all patients who have received at least one dose of sapacitabine. The primary endpoint was 1-year survival. The trial is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00590187).

Results

A total of 105 patients were treated including 86 patients with previously untreated and 19 patients with first relapsed AML. The median age was 77 years (range 70-91). Among the 60 randomized patients, the 1-year survival rates were 35% in arm A (95% CI, 16 to 59%), 10% in arm B (95% CI, 2 to 33%), and 30% in arm C (95% CI, 13 to 54%). The overall response rates were 45% on arm A (2 CRs, 1 CRi, and 6 HIs), 30% on arm B (1 CR, 1 CRp, 1 PR and 3 HIs), and 45% on arm C (5 CRs, 1 CRi and 3 HIs) with more complete remissions (CR) occurring on arm C (25%) as compared to arm A (10%) and arm B (5%). The 30-day mortality was 13% and 60-day mortality was 26%. The most common grade 3-4 adverse events were anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, febrile neutropenia and pneumonia. The most common serious adverse events were myelosuppression-related complications with febrile neutropenia and pneumonia being the most common ones.

Conclusion

Sapacitabine is active in elderly patients with AML and is well-tolerated. The 400 mg dose schedule has better efficacy profile. Future investigations aim to combine sapacitabine with other low-intensity therapies in elderly patients with AML.

INTRODUCTION

Despite significant progress in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), modern intensive chemotherapy results in a cure rate of only 30% to 50%. Intensive chemotherapy does not benefit most elderly patients with AML, because of poor tolerance to chemotherapy, high rates of treatment-related mortality (30%-50%), and high incidence of adverse cytogenetic abnormalities.1-4 Despite complete remission (CR) rates of 40%-50%, the median survival in elderly patients treated with intensive chemotherapy is only 4-6 months. These results have not changed in the past 2 decades despite variations in intensive chemotherapy regimens and improvements in supportive care measures. 3 Recent investigations have evaluated low-intensity therapies with hypomethylating drugs (decitabine, azacitidine) and other agents (low-dose cytarabine, gemtuzumab ozogamicin, clofarabine).5-10 Developing novel drugs with new mechanisms of action, improved anti-leukemic activity, and more favorable safety profiles is important.

Nucleoside analogs are a major class of antitumor cytotoxic agents. Several were active in leukemia (cladribine, clofarabine, cytarabine, azacitidine, decitabine). Oral sapacitabine, 1-(2-C-cyano-2-deoxy- ß-D-arabino-pentafuranosyl)-N4-palmitoylcytosine, (also known as CYC682, CS-682) is a rationally designed analog of cytarabine with a unique mechanism of action.11 Following oral administration, sapacitabine is converted to 2-C-cyano-2-deoxy-ß(-D-arabino-pentafuranosyl) cytosine (CNDAC). After phosphorylation to the triphosphate form and incorporation into DNA, replication is not inhibited at cytotoxic concentrations (in contrast to cytarabine and clofarabine). Instead, after further polymerization, the strong electrophilic properties of the cyano group of CNDAC causes a rearrangement of the nucleotide to a form that lacks a 3’-hydroxyl moiety.12,13 This results in a single strand DNA break that is repaired to only a small extent. On a subsequent round of DNA replication unrepaired single strand DNA breaks are converted to double strand breaks, causing cell death.14,15

A phase I study of oral sapacitabine given twice daily for 7 days, and twice daily for 3 days every week for 2 weeks, every 3-4 weeks, demonstrated the safety and efficacy of sapacitabine in AML. The recommended phase II dose schedules were 325 mg twice daily for 7 days and 425 mg twice daily for 3 days, days 1-3 and 8-10. Dose limiting toxicities were gastrointestinal. Among 47 patients treated for refractory-relapsed AML, 13 (28%) achieved responses, including 4 complete remissions.16

The current multicenter phase II randomized study investigated three dose schedules in elderly patients with AML: 200 mg orally twice daily for 7 days, 300 mg orally twice daily for 7 days, and 400 mg orally twice daily for 3 days each week for 2 weeks, for 28-day cycle. This study aims to select a dosing schedule with the better 1-year survival rate.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Eligibility

Patients aged 70 years or older with AML, either previously untreated or in first relapse, were eligible for this study after informed consent was signed according to institutional guidelines and in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Other eligibility criteria included: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance 0-2; adequate hepatic function (bilirubin ≤ 1·5 x upper limit of normal (ULN) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ≤ 2·5 times ULN or ≤ 5 x ULN if hepatic leukemic involvement was suspected; adequate renal function (creatinine ≤ 1·5 x ULN); no prior chemotherapy for AML, radiation therapy, or investigational therapies for at least 2 weeks, with recovery from clinically significant toxicities of these prior treatments. Patients with white blood cell counts (WBC) 50 × 109/L or higher were allowed to receive hydroxyurea for cytoreduction prior to starting sapacitabine. Additional exclusion criteria were the presence of central nervous system disease, uncontrolled concurrent illnesses including active infections, active cancers, symptomatic congestive heart failure, unstable angina, cardiac arrhythmias, or psychiatric illnesses/social situations limiting compliance with the study requirements.

Study Design and Treatment Plan

This was a multi-institutional randomized phase II study of three schedules of oral sapacitabine in elderly patients with previously untreated or first relapsed AML: Arm A - 200 mg orally twice daily (b.i.d.) for 7 days; Arm B - 300 mg orally b.i.d. for 7 days; and Arm C - 400 mg orally b.i.d. for 3 days each week for 2 weeks for 28-day cycles. An initial cohort of 20 patients per treatment arm was planned for a total of 60 patients. Following the experience with the three schedules, expanded cohorts of 20 to 25 patients were treated with the schedules associated with at least 4 CR and CRi, and a 30-day death rate of 20% or less, to confirm the safety and tolerability of the corresponding dosing schedules.

Courses of therapy were repeated every 28 days. Dosing for the next cycle did not start until clinically significant and drug-related non-hematologic toxicities had resolved to ≤ grade 1 or baseline. After recovery, a dose reduction of 50 mg twice daily was required for grade 3-4 drug-related non-hematologic toxicities. Dose reductions for grade 2 toxicities were allowed for frail patients. Dose reductions for hematological toxicities were guided by findings from bone marrow and time to absolute neutrophil count (ANC) and platelet count recovery. A dose reduction of 50 mg twice daily was required for a delay in blood counts recovery to best level on study beyond day 42 if bone marrow blasts decreased 25% or more from baseline but remained more than 5%. If the blasts were less than 5%, dose reduction of 100 mg twice daily was required for persistent cytopenias as described above. For patients who were assigned to the 200 mg twice daily arm (Arm A) and tolerated treatment well, intra-patient dose escalation up to 300 mg twice daily for 7 days was allowed. Patients could continue treatment indefinitely as long as there was no evidence of clinically significant AML progression. Prophylactic use of antibiotics and therapeutic use of growth factors were allowed according to institutional guidelines. Prophylactic use of hematopoietic growth factors was not allowed.

Randomization and Masking

Randomization was implemented at the International Drug Development Institute (IDDI, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium) using a fully validated Interactive Web-based Randomization Service (IWRS). The algorithm used for treatment allocation was a dynamic randomization with a minimization probability of 80%, therefore treatment allocations were completely unpredictable. Patients were stratified by previously treated vs. previously untreated and randomized in a ratio of 1:1:1. This was an open-label study so the investigators and patients were not masked.

Statistical Analysis

The primary objective was the evaluation of the 1-year survival rate with the three dosing schedules. Secondary objectives were to assess the rates of complete remission (CR), CR with incomplete platelet count recovery (CRp), partial remission (PR), CR with incomplete blood count recovery (CRi), or hematologic improvement (HI), and corresponding durations, transfusion requirements and number of hospitalized days. Statistical computations were done with SAS 9.2, JMP 8.0.1 and VassarStat (http://VassarStats.net),

The intent-to treatment population includes all patients who have received at least one dose of sapacitabine. The primary efficacy endpoint of 1-year survival was measured from the date of randomization and was reported with 95% confidence interval. Time to event endpoints such as overall survival and response durations were estimated by the method of Kaplan and Meier. Logistic models were used for 30-day mortality and 60-day mortality and Cox proportional hazard model were used in prognostic factor analysis.

A Bayesian continuous futility monitoring rule was used for each dose schedule separately based on the rate of CR plus CRi as follows: the enrollment to a dose schedule would be stopped if there was less than a 5% chance that the rate of CR+CRi was greater than 25% from the data obtained from patients who had been treated on that dose schedule. A “selection” design was used to choose the better dosing schedule based on the 1-year survival rate if all 3 dosing schedules were found to have activity based on the rate of CR plus CRi. If the better dosing schedule had a true 1-year rate of 45% and the worse dosing schedule a true 1-year rate of 30%, the trial had better than 80% probability to choose the correct dosing schedule with 20 patients treated with each dosing schedule. This randomized phase II trial was not expected to have sufficient power to compare the 3 dosing regimens for 1-year survival. If a dosing schedule had at least 4 CR and CRi, and the 30-day death rate was 20% or less, additional patients might be added to confirm the safety and tolerability of that dosing schedule. Promising dosing schedules would be expanded sequentially (non-random) because each dosing schedule might reach the expansion criteria at different times.

Response and Toxicity Criteria

Bone marrow biopsy and/or aspirate was performed at baseline, prior to starting cycle 2 and as indicated thereafter. A CR was defined as normalization of the blood and marrow with 5% or fewer marrow blasts, independence of transfusions, a granulocyte count of 109/L or greater, and a platelet count of 100 × 109/L or greater.17,18 A PR was defined the same as CR but with at least 50% decrease in marrow blasts and to a level of 6% or more. A CRp was defined the same as CR but without platelet count recovery to 100 × 109/L or greater. A CRi or marrow CR was defined the same as CR but without granulocyte or platelet count recovery. Hematologic improvement (HI) was defined according to the International Working Group criteria.18

Prognostic Factor Analysis

The following factors were used in univariate and multivariable analyses to assess the effect on 30-day mortality, 60-day mortality and 1- year survival: age (70-74 vs. 75-79 vs. ≥ 80 years), ECOG (0-1 vs. 2), peripheral white blood cell counts (< 10 vs. ≥ 10 × 109 /L), platelet counts (< 50 vs. ≥ 50 × 109 /L), creatinine (≤ ULN vs. > ULN), bone marrow blasts (<50% vs. ≥ 50%), AML type (de novo vs. other), previous treatment (newly vs. first relapsed), treatment arm (Arm A vs. Arm B vs. Arm C), cytogenetic risk by Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) classification (unfavorable vs. intermediate/unknown or missing), and chromosomal abnormalities (complex (3 or more abnormalities) vs. noncomplex (1 or 2 abnormalities) vs. others). Logistic models were used for 30-day mortality and 60-day mortality and Cox proportional hazard model was used for 1- year survival. A two-sided p value of less than 0.1 was used to select the significant factors to be included in the multivariate analyses. A two-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Study Group

The study enrolled 107 patients from 12 medical centers. The first patient was enrolled on Dec 27, 2007 and last patient was enrolled on April 21, 2009. The median length of follow-up is 143 weeks (interquartile range, 19 weeks). Two patients did not receive treatment: one patient died and another one was found to be ineligible prior to receiving the first dose of study drug. After evaluation of the first 60 patients, randomly assigned in equal numbers of 20 patients to each treatment arm, favorable preliminary results were observed in Arms A and C leading to the selective expansion of these two arms, including an additional 20 patients in Arm A and 25 patients in Arm C, for a total number of 105 patients. Because time to response varies from 2 to 9 cycles, it is not possible to expand all promising dosing schedules by random assignment. Arm A was expanded first and Arm C was expanded after the expanded Arm A reached 20 patients.

Patient characteristics are detailed in Table 1. Median age was 77 years (range 70 to 91 years); 31 patients (30%) were 80 years or older. ECOG performance status was 2 in 17 patients (16%). Fifty patients (48%) had AML following myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) or myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN), or secondary to therapy for other primary cancers. Eighty-six patients (82%) had untreated newly diagnosed AML; 19 (18%) received sapacitabine for first relapse. Prior treatment for AML included ara-C (n=13), anthracycline or anthracenedione (n=11), and hypomethylating agents (n=8). Among patients with newly diagnosed AML, unfavorable cytogenetics were present in 35 patients (41%).19 Fifty-nine patients (56%) required transfusion of packed red blood cells, platelets or both prior to study entry.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Group (n=105)

| No of Patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Arm A (n=20) | Arm A – Expanded (n=20) | Arm B (n=20) | Arm C (n=20) | Arm C – Expanded (n=25) | Total (n=105) |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 70 – 79 | 11 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 21 | 74 |

| 80 or older | 9 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 31 |

| Male sex | 11 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 61 |

| Performance Status 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 17 |

| Untreated | 16 | 19 | 17 | 15 | 19 | 86 |

| De novo | 9 | 11 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 38 |

| Preceded by MDS/MPN | 6/0 | 6/1 | 11/2 | 6/2 | 9/1 | 38/6 |

| Treatment-related | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 3 |

| Other | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| First Relapsed | 4 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 19 |

| De novo | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 14 |

| Preceded by MDS/MPN | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Treatment-related | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Other | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| CR duration | ||||||

| < 6 months | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| ≥ 6 months | 3 | - | 2 | 4 | 4 | 13 |

| Unknown | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Cytogenetics risk | ||||||

| Favorable | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Intermediate | 13 | 9 | 6 | 10 | 13 | 51 |

| Unfavorable | 6 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 41 |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 4 |

| Missing/inevaluable | - | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 8 |

| Bone marrow blasts ≥ 50% | 8 | 7 | 7 | 11 | 8 | 41 |

MDS = Myelodysplastic syndromes; MPN = Myeloproliferative neoplasia

Arm A - 200 mg orally twice daily for 7 days; Arm B - 300 mg orally twice daily for 7 days; and Arm C - 400 mg orally twice daily for 3 days weekly for 2 weeks

Patient characteristics were similar among the 60 randomized patients but more patients with AML preceded by MDS/MPD were on Arm B and more patients with unfavorable cytogenetics were on Arm B and Arm C.

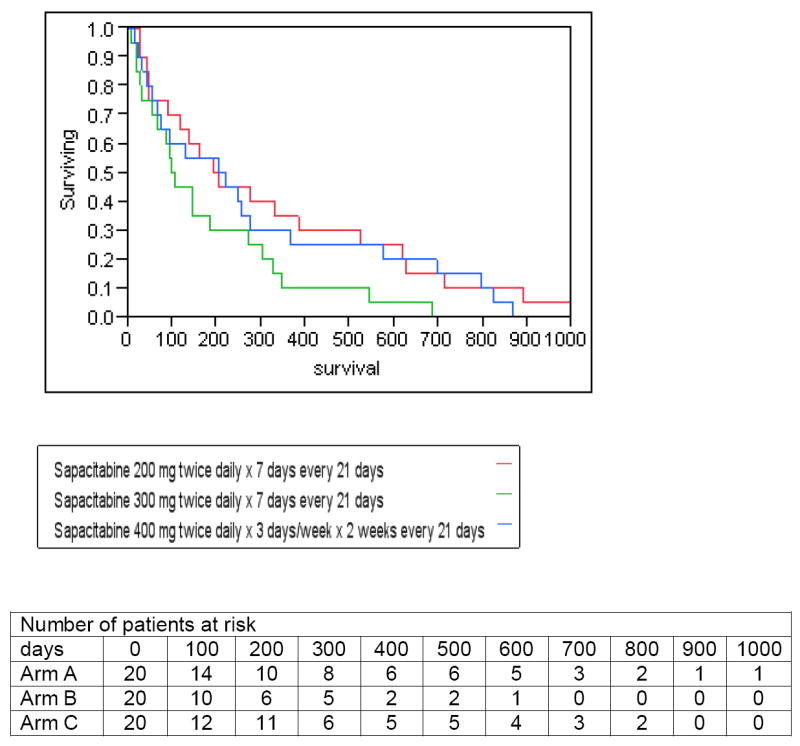

Survival

As of the data cutoff date of July 2011, 101 patients have died. Among the original cohort of 60 patients who underwent randomization, the 1-year survival rates were 35% in Arm A (95% CI, 16 to 59%), 10% in Arm B (95% CI, 2 to 33%) and 30% in Arm C (95% CI, 13 to 54%). Median survival was 197 (95% CI, 26 to 892 days), 105 (95% CI, 6 to 685 days), and 213 days (95% CI, 13 to 821 days), respectively (Figure 1). The 1-year survival rate in the expanded Arm A was 10% (95% CI, 2 to 33%) with median survival of 151 days (95% CI, 17 to 708 days) and in the expanded Arm C was 24% (95% CI, 10 to 46%) with median survival of 159 days (95% CI, 17 to 673 days).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram showing (A) patients enrolled and (B) subsequent random assignment to treatment and treatment received. Two patients did not receive treatment and were not included in the safety and efficacy analysis (C). Both patients were from the 200 mg cohort. One patient withdrew consent and the other was found to be ineligible.

Among 105 patients, 36 patients responded with CR (n=12), CRp (n=1), CRi (n=3), PR (n=3), and HI (n=17). Twenty-eight responders were previously untreated: CR (n=9), CRp (n=1), CRi (n=3), PR (n=2), and HI (n=13). Eight responders were in first relapse: CR (n=3), PR (n=1) and HI (n=4). The median survival of CR patients (n=12) was 525 days (95% CI, 192 to 798 days). The median survival of patients achieving other types of responses (n=24) was 277 days (95% CI, 228 to 542 days).

In the subgroup of 28 patients with de novo AML who underwent randomization, the 1-year survival rates were 17% on Arm A (n=12), 0% on Arm B (n=5) and 36% on Arm C (n=11). In the subgroup of 29 patients with AML following MDS and/or MPD who underwent randomization, the 1-year survival rates were 57% on Arm A (n=7), 8% on Arm B (n=13) and 22% on Arm C (n=9). Among 23 patients who survived 1 year or more, 7 patients achieved CRs, 2 achieved PRs, 7 major HIs and 4 had stable diseases defined as staying on study longer than 16 weeks without clinically significant progression. The patient who was on study the longest i.e., receiving a total of 30 cycles, achieved a PR. These subgroup analyses should be considered exploratory and hypothesis generating.

Responses

After the first 60 patients were randomized and treated, 20 in each of the 3 treatment arms, the response rates were 45% in Arm A, 30% in Arm B, and 45% in Arm C. There were 8 CRs (13%), 1 CRp, 2 CRis, 1 PR, and 12 HIs (20%). The median duration of CR or CRp was 197 days (95% CI, 28 to 468 days) and the median duration of other responses was 70 days (95% CI, 14 to 77 days). Five CRs occurred on the dosing schedule of 400 mg orally twice daily for 3 days weekly for 2 weeks (25%) and 2 CRs on the dosing schedule of 200 mg twice daily for 7 days (10%). Following review of the data, a decision was made to expand the experience in Arm A with 20 additional patients, and in Arm C, with 25 additional patients. The respective response rates were 30% on both expanded cohorts (Table 2).

Table 2.

Outcome of Patients by Treatment Arm and Overall

| Efficacy Parameter | Arm A (n=20) |

Arm A – Expanded (n=20) |

Arm B (n=20) |

Arm C (n=20) |

Arm C – Expanded (n=25) |

Total (n=105) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 1-year survival (%) | 35 | 10 | 10 | 30 | 24 | 22 |

| 95% confidence interval | 16-59 | 2-33 | 2-33 | 13-54 | 10-46 | 15-31 |

|

| ||||||

| Median survival in days (range) | 197 (26 -892) | 151 (17 -708) | 102 (6 -685) | 213 (13 -821) | 159 (17 -673) | 158 (6 – 892) |

| 95% confidence interval | 48 -385 | 39 -225 | 32 -186 | 56 -277 | 76-236 | 96 -215 |

|

| ||||||

| No. Response (%) | 9 (45) | 6 (30) | 6 (30) | 9 (45) | 6 (24) | 36 (34) |

| 95% confidence interval | 24-68 | 13-54 | 13-54 | 24-68 | 10-46 | 25-44 |

|

| ||||||

| CR | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 12 |

|

| ||||||

| CRp | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

|

| ||||||

| CRi | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | 3 |

|

| ||||||

| PR | - | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 3 |

|

| ||||||

| HI | 6 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 17 |

Arm A - 200 mg twice daily for 7 days; Arm B - 300 mg twice daily for 7 days; and Arm C - 400 mg orally twice daily for 3 days weekly for 2 weeks

Transfusion and hospitalization

Among 60 randomized patients, the mean number of packed red blood cells transfused per patient after enrolling on the study was similar on Arm A (17 units/patient) and Arm C (16 units/patient) but was higher on Arm B (21 units/patient). More platelet transfusions were required on Arm B (44 units/patient) as compared to that required on Arm A (24 units/patient) and Arm C (27 units/patient). The percentage of days spent in hospital while on study was similar on Arm A (8%) and Arm C (8%) but was higher on Arm B (19%).

Among 45 patients in the expanded Arm A and Arm C (non-randomized), the mean number of packed red blood cells transfused per patient was 10 units and 14 units/patient; the mean number of platelets transfused was 9 unites and 14 unites/patient; and the percentage of days spent in hospital while on study was 15% and 10% respectively.

Prognostic Factors for Early Mortality and 1-year Survival

A multivariable analysis of prognostic factors associated with 30-day mortality identified thrombocytopenia < 50 × 109/L as an adverse factor. No prognostic factors were found to be associated with 60-day mortality. The independent adverse factors for 1-year survival were: thrombocytopenia < 50 × 109/L, creatinine > ULN, and unfavorable cytogenetic risk by SWOG. The p-values, hazard ratios and odds ratios are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis of Prognostic Factors Associated with 30-day Mortality, 60-day Mortality and 1-year Survival (n=105)

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Factors for 30-day mortality | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

| ECOG = 2 | 5.5 (1.6, 18.7) | 0.007 | 4.0 (0.9, 17.3) | 0.068 |

| Platelet count < 50 × 109/L | 8.6 (1.8, 40.7) | 0.0067 | 7.5 (1.5, 39.0) | 0.0156 |

| Creatinine > upper limit of normal | 4.9 (1.5, 16.7) | 0.0103 | 4.1 (1.0, 17.2) | 0.057 |

| Bone marrow blasts ≥ 50% | 3.5 (1.1, 11.3) | 0.0375 | 2.9 (0.7, 12.5) | 0.164 |

| Diagnosis of de novo AML | 2.9 (0.9, 10.0) | 0.0882 | 1.9 (0.4, 8.7) | 0.385 |

| Adverse Factors for 60-day mortality | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

| ECOG = 2 | 3.2 (1.1, 9.5) | 0.0333 | 2.5 (0.8, 8.2) | 0.128 |

| Platelet count < 50 × 109/L | 3.0 (1.2, 7.5) | 0.0206 | 2.6 (1.0, 7.0) | 0.054 |

| Creatinine > upper limit of normal | 3.8 (1.3, 11.1) | 0.0129 | 3.1 (1.0, 9.7) | 0.050 |

| Bone marrow blasts ≥ 50% | 2.7 (1.1, 6.5) | 0.0330 | 2.6 (1.0, 6.8) | 0.052 |

| 1-Year Survival | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | P-value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

| ECOG = 2 | 1.7 (0.9, 2.9) | 0.0891 | 1.7 (0.9, 3.1) | 0.084 |

| Peripheral white blood cell count ≥ 10 × 109 /L | 1.5 (1.0, 2.3) | 0.0767 | 1.3 (0.8, 2.1) | 0.264 |

| Platelet count < 50 × 109/L | 2.6 (1.7, 4.0) | <0.0001 | 2.4 (1.5, 3.9) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine > upper limit of normal | 2.0 (1.2, 3.5) | 0.009 | 1.6 (0.9, 2.8) | 0.098 |

| Unfavorable by SWOG cytogenetic risk | 1.8 (1.1, 2.7) | 0.0122 | 1.6 (1.0, 2.5) | 0.044 |

Toxicity

Overall, 14 patients died during the first 30 days on study (13%) and 27 patients (26%) died within 60 days of study entry. The 30-day and 60-day mortality (10%, 25%) were the same between Arm A and Arm C but higher on Arm B (20%, 30%). Four deaths were considered by study site investigator to be probably or possibly related to sapacitabine: pneumonia (n=1), sepsis (n=1), cerebral hemorrhage (n=1) and neutropenic colitis (n=1).

The median numbers of cycles per treatment arm and the number of patients with sapacitabine dose reductions in subsequent cycles are shown in Table 4. Adverse events, listed as the maximum grade in all cycles, regardless of causality, by the three treatment arms are detailed in Table 5. The most common grade 3-4 adverse events were anemia (n=35), neutropenia (n=35), thrombocytopenia (n=58), febrile neutropenia (n=47) and pneumonia (n=22). The most common serious adverse events were myelosuppression-related complications with febrile neutropenia and pneumonia being the most common ones. The most common non-hematological adverse events were gastrointestinal. Most of the gastrointestinal symptoms were grade 1 or 2 (90%). Gastrointestinal symptoms were manageable and only 2% resulted in dose reduction. More patients experienced grade 3-4 anemia and pneumonia on Arm B. The toxicities in the previously untreated patients were similar to those in the first relapsed patients (Table 6). There were 10 cases of death from sepsis: 6 on Arm A (15%), 3 on Arm B (15%) and 1 on Arm C (2%). There were two cases of neutropenic colitis and one resulted in death. One occurred on the dose schedule of 200 mg twice daily for 7 days and the other on the dose schedule of 300 mg twice daily for 7 days.

Table 4.

Safety of Sapacitabine Schedules and Treatment Delivery

| Safety Parameter | Arm A (n=20) |

Arm A – Expanded (n=20) |

Arm B (n=20) |

Arm C (n=20) |

Arm C – Expanded (n=25) |

Total (n=105) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| No(%) with 30-day mortality | 2 (10) | 3 (15) | 4 (20) | 2 (10) | 3 (12) | 14 (13) |

| 95% confidence interval | 2-33 | 4-39 | 7-44 | 2-33 | 3-32 | 8-22 |

|

| ||||||

| No(%) with 60-day mortality | 5 (25) | 5 (25) | 6 (30) | 5 (25) | 6 (24) | 27 (26) |

| 95% confidence interval | 10-49 | 10-49 | 13-54 | 10-49 | 10-46 | 18-35 |

|

| ||||||

| Number of cycles; median (range) | 3 (1 - > 23) | 3 (1 - > 22) | 3 (1 - 9) | 3 (1 - 23) | 2 (1 - > 17) | 3 (1 - > 23) |

|

| ||||||

| No. patients treated with ≥ 4 cycles | 8 | 4 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 33 |

|

| ||||||

| No. (%) patients with dose reductions | 3 (15) | 3 (15) | 9 (45) | 8 (40) | 13 (52) | 36 (34) |

| 95% confidence interval | 4-39 | 4-39 | 24-68 | 20-64 | 32-72 | 25-44 |

Arm A - 200 mg orally twice daily for 7 days; Arm B - 300 mg orally twice daily for 7 days; and Arm C - 400 mg orally twice daily for 3 days weekly for 2 weeks

Table 5.

Adverse Events Occurring in > 15% Patients on Assigned Dosing Schedule, Listed as the Maximum Grade of All Cycles, Regardless of Causality

| No. Patients | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arm A (n = 40)* | Arm B (n = 20) | Arm C (n = 45)* | Fisher’s Exact Test | |||||||

| Preferred Term | Gr 1-2 | Gr 3-4 | Gr 5 | Gr 1-2 | Gr 3-4 | Gr 5 | Gr 1-2 | Gr 3-4 | Gr 5 | P-value |

| Anemia | 4 | 8 | - | - | 12 | 4 | 15 | - | 0.08 | |

| Febrile neutropenia | - | 16 | - | - | 9 | - | - | 22 | - | 0.01 |

| Neutropenia | - | 14 | - | - | 10 | - | 2 | 11 | - | 0.41 |

| Thrombocytopenia | - | 24 | - | - | 12 | - | - | 22 | - | 0.02 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2 | 2 | - | 2 | 2 | - | 2 | 4 | - | 0.96 |

| Abdominal pain | 6 | 4 | - | 3 | - | - | 1 | 2 | - | 0.05 |

| Constipation | 10 | 1 | - | 8 | 1 | - | 11 | - | - | 0.87 |

| Diarrhea | 23 | 2 | - | 11 | 2 | 17 | 3 | - | 0.07 | |

| Nausea | 16 | 1 | - | 6 | - | - | 23 | 2 | - | 0.001 |

| Stomatitis | 4 | - | - | 2 | - | - | 7 | - | - | 0.23 |

| Vomiting | 12 | - | - | 5 | - | - | 11 | 1 | - | 0.14 |

| Fatigue | 19 | 3 | - | 10 | 1 | - | 13 | 4 | - | 0.11 |

| Peripheral edema | 5 | 1 | - | 8 | - | - | 15 | 2 | - | 0.03 |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 1 | 1 | - | 2 | 3 | - | - | - | - | 0.12 |

| Fever | 6 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 9 | - | - | 0.02 |

| Bacteremia | 2 | 5 | - | 1 | - | 2 | - | 5 | - | 0.03 |

| Cellulitis | 3 | 3 | - | - | 3 | - | 3 | 5 | - | 0.38 |

| Pneumonia | 1 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 3 | 0.70 |

| Sepsis | - | 3 | 6 | - | - | 3 | - | 1 | 1 | 0.08 |

| Anorexia | 9 | 1 | - | 5 | - | - | 8 | - | - | 0.49 |

| Weight decreased | 3 | - | - | 4 | - | - | 3 | 1 | - | 0.99 |

| Hypokalemia | 3 | 2 | - | - | 1 | - | 4 | 3 | - | 0.21 |

| Arthralgia | 7 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 5 | 1 | - | 0.02 |

| Back pain | 4 | 2 | - | 1 | - | - | 6 | - | - | 0.08 |

| Musculoskeletal chest pain | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 6 | 2 | - | 0.006 |

| Pain in the extremity | 7 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 8 | - | - | 0.03 |

| Dizziness | 7 | - | - | 3 | - | - | 10 | - | - | 0.126 |

| Headache | 7 | - | - | - | - | - | 6 | 3 | - | 0.002 |

| Insomnia | 4 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 7 | - | - | 0.08 |

| Cough | 9 | - | - | 3 | - | - | 6 | - | - | 0.19 |

| Dyspnea | 15 | 2 | - | 2 | - | - | 10 | 2 | - | 0.001 |

| Epistaxis | 6 | - | - | 3 | 1 | - | 5 | - | - | 0.68 |

| Ecchymosis | 4 | 1 | - | 3 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - | 0.77 |

| Petechiae | 4 | 1 | - | 3 | - | - | 7 | - | - | 0.40 |

| Alopecia | 7 | - | - | 2 | - | - | 10 | - | - | 0.04 |

| Rash | 5 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - | 7 | 1 | - | 0.16 |

| Hypotension | 4 | 2 | - | - | - | - | 3 | 4 | - | 0.04 |

Arm A - 200 mg orally twice daily for 7 days; Arm B - 300 mg twice daily for 7 days; and Arm C - 400 mg twice daily for 3 days weekly for 2 weeks

Including additional patients in the expanded Arm A and expanded Arm C

Table 6.

Adverse Events Occurring in > 15% Patients (Previously untreated versus First Relapsed AML) on Assigned Dosing Schedule, Listed as the Maximum Grade of All Cycles, Regardless of Causality

| No. Patients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previously Untreated (n = 86)* | First Relapsed (n=19)* | Fisher’s Exact Test | |||||

| Preferred Term | Gr 1-2 | Gr 3-4 | Gr 5 | Gr 1-2 | Gr 3-4 | Gr 5 | P-value |

| Anemia | 6 | 29 | - | 2 | 6 | 0.85 | |

| Febrile neutropenia | - | 39 | - | - | 8 | - | 1 |

| Neutropenia | 2 | 29 | - | - | 6 | - | 1 |

| Thrombocytopenia | - | 48 | - | - | 10 | - | 0.80 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 5 | 5 | - | 1 | 3 | - | 0.31 |

| Abdominal pain | 11 | 5 | - | 1 | 1 | - | 0.87 |

| Constipation | 28 | 2 | - | 1 | - | - | 0.031 |

| Diarrhea | 41 | 5 | - | 10 | 2 | 0.57 | |

| Nausea | 35 | 3 | - | 10 | - | - | 0.7 |

| Vomiting | 22 | 1 | - | 6 | - | - | 0.66 |

| Fatigue | 33 | 6 | - | 9 | 2 | - | 0.58 |

| Peripheral edema | 23 | 3 | - | 5 | - | - | 1 |

| Fever | 11 | 1 | - | 5 | - | - | 0.32 |

| Candidiasis or oral candidiasis | 8 | - | - | 5 | 1 | - | 0.01 |

| Cellulitis | 4 | 7 | - | 2 | 4 | - | 0.07 |

| Pneumonia | 2 | 19 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0.78 |

| Anorexia | 19 | 1 | - | 3 | - | - | 0.80 |

| Hypokalemia | 6 | 3 | - | 1 | 3 | - | 0.11 |

| Hypophosphatemia | - | 3 | - | 1 | 3 | - | 0.02 |

| Arthralgia | 9 | 1 | - | 3 | - | - | 0.55 |

| Back pain | 7 | 2 | - | 4 | - | - | 0.23 |

| Muscle spasm | 2 | - | - | 3 | - | - | 0.04 |

| Musculoskeletal chest pain | 3 | 3 | - | 4 | - | - | 0.03 |

| Pain in the extremity | 14 | - | - | 2 | - | - | 0.73 |

| Dizziness | 15 | - | - | 5 | - | - | 0.35 |

| Headache | 12 | 2 | - | 1 | 1 | - | 0.39 |

| Cough | 16 | - | - | 2 | - | - | 0.52 |

| Dyspnea | 22 | 2 | - | 5 | 2 | - | 0.24 |

| Epistaxis | 12 | 1 | - | 2 | - | - | 1 |

| Petechiae | 10 | - | - | 4 | - | - | 0.28 |

| Alopecia | 15 | - | - | 4 | - | - | 0.74 |

| Rash | 12 | 1 | - | 2 | - | - | 1 |

| Hypotension | 6 | 4 | - | 1 | 2 | - | 0.52 |

Including randomized patients and additional patients in the expanded Arm A and expanded Arm C

DISCUSSION

This randomized phase II study aimed to define a schedule with better efficacy and safety profile for sapacitabine, to be used in future phase III randomized studies. Sapacitabine showed encouraging efficacy against AML with reasonable toxicity. Among 105 patients 70 years or older with newly diagnosed or first relapsed AML, the 1-year survival rate was 22% (95% CI, 15 to 31%), the 30-day all cause mortality was 13%, and 60-day all cause mortality 26%. One-year survival was 27% for 45 patients treated with sapacitabine 400 mg orally twice daily for 3 days weekly for 2 weeks (4800 mg per course) and 22% for 40 patients treated with 200 mg twice daily for 7 days (2800 mg per course) of each 28-day cycle. Among 86 patients with newly diagnosed AML, 9 patients lived for 2 years or longer; 7 were treated with the 400 mg dose schedule (21%) and 2 were treated with the 200 mg dose schedule (6%). Toxicities were mostly myelosuppression-associated, and related to the pretreatment compromised marrow in AML, and the known myelosuppression effect of sapacitabine. The major non-hematological toxicities were gastrointestinal mostly mild to moderate. According to the “selection” design hypothesis, the 200 mg and 400 mg dose schedules had the better 1-year survival rates, 35% and 30%, respectively. However, the 1-year survival rate in the expanded cohort of the 200 mg dose schedule was lower (10%). The 1-year survival rate in the expanded cohort of the 400 mg (24%) was consistent with that observed in the randomized cohort (30%). Overall, the 400 mg dose schedule appears to have a better efficacy profile of consistent 1-year survival rates and more CRs. However, all patients who achieved CRs on the 400 mg cohort were dose reduced for myelosuppression. This suggests that a lower dose should be used if sapacitabine is to be combined with another myelosuppresive agent. The strength of this study is the random assignment of 3 dose schedules, which provides a certain degree of balance in patient and disease characteristics. The limitation of the study is its small sample size which does not allow formal statistical comparison among the 3 dose schedules. Because of the overall small sample size and the heterogeneity of the patient population, a larger randomized study is required to confirm the findings from this study.

The outcome in elderly patients with AML is poor. In clinical practice, a substantial proportion of older patients are not treated with intensive treatment by choice or because it is considered unsuitable. Unsuitable can mean that the patient is medically unfit and such treatment might curtail survival, or the patient is medically fit but unlikely to benefit due to adverse disease features (e.g, cytogenetics or secondary disease).20

Targeted therapies against AML signaling pathways, such as FLT3 inhibitors have yielded favorable results but are limited to patients with the appropriate target.21 Targeted therapies may be given alone, or in combination with intensive chemotherapy in younger patients or with low intensity therapy in older patients. Hypomethylating agents have also shown encouraging results with low treatment associated mortality and reasonable survival rates, despite the low rate of objective CRs.9,10 This suggests that improving survival in elderly AML may be possible by controlling the disease with low-intensity therapy with favorable safety profiles rather than by achieving higher CR rates with intensive, toxic therapy. A randomized study evaluating decitabine versus low dose cytarabine in older patients with AML showed an improvement in median survival with decitabine despite a CR rate of only 18%.22 Additional studies are ongoing with other adenosine nucleoside analogs, including clofarabine. A Medical Research Council (MRC) trial, using a “pick the winner” design, is evaluating low-dose clofarabine vs. low-dose cytarabine in elderly patients with AML. If one or more such low-intensity therapies are confirmed to be active and safe, combined modality therapies may improve outcome in this poor prognosis group. Combination regimens involving clofarabine and low-dose ara-C alternating with hypomethylating agents are ongoing.23 A pilot study evaluating sapacitabine administered by the 3-day schedule at 300 mg orally twice daily for 3 days each week for 2 weeks in alternating cycles with decitabine has generated favorable safety and efficacy results.24 The oral nature of sapacitabine allows multiple cycles to be given at home as compared to the need for multiple office visits for anti-leukemic drugs that require intravenous administration. This is important for elderly patients if the treatment goal is to prolong survival with good quality of life. A randomized phase 3 study evaluating sapacitabine administered by the 3-day schedule in alternating cycles with decitabine versus decitabine alone is ongoing to establish the safety and efficacy of sapacitabine in the treatment of elderly AML.

Research in Context

Systemic review - We convened an international panel of AML experts to review the current treatment options for older patients with AML. All agreed that current treatments were not adequate and new safe and effective therapies were urgently needed. Sapacitabine is an oral nucleoside analogue with a novel mechanism of action and has induced CR, CRp, and CRi in AML and MDS in a Phase 1 study. Because of its favorable safety profile and the oral route of administration, sapacitabine can be administered in the outpatient setting for prolonged periods of time with the potential to improve the survival of elderly patients suffering from this life-threatening disease.

Interpretation - Sapacitabine is active in elderly patients with AML and could be orally administered in the outpatient setting for prolonged period of time. Improving survival in elderly AML is possible by controlling the disease with low-intensity therapy with favorable safety profiles rather than by achieving higher CR rates with intensive, toxic therapy. Sapacitabine in combination with low-intensity therapy is being evaluated in a large randomized Phase 3 study with the primary efficacy endpoint of overall survival. This Phase 3 study (n=485) compares sapacitabine administered in alternating cycles with decitabine against decitabine.

Figure 2.

Survival of patients by Sapacitabine treatment arm

Acknowledgments

Supported by research funding from Cyclacel Limited, Dundee, UK

Footnotes

Grant support: CA100632 from the National Cancer Institute, Department of Health and Human Services.

Contributors:

Concept and Design: Hagop Kantarjian, Judy Chiao and William Plunkett

Provision of study material or patients: Hagop Kantarjian, Stefan Faderl, Guillermo Garcia-Manero, Selina Luger, Parameswaran Venugopal, Lori Maness, Meir Wetzler, Steven Coutre, Wendy Stock, David Claxton, Stuart L. Goldberg, Martha Arellano, Stephen A. Strickland, Karen Seiter, Gary Schiller, and Elias Jabbour.

Data analysis and interpretation: Hagop Kantarjian, Selina Luger, Parameswaran Venugopal, Lori Maness, Meir Wetzler, Steven Coutre, Wendy Stock, David Claxton, Stuart L. Goldberg, Martha Arellano, Stephen A. Strickland, Karen Seiter, Gary Schiller and Judy Chiao.

Manuscript writing: H Kantarjian

Final approval of manuscript: Hagop Kantarjian, Stefan Faderl, Guillermo Garcia-Manero, Selina Luger, Parameswaran Venugopal, Lori Maness, Meir Wetzler, Steven Coutre, Wendy Stock, David Claxton, Stuart L. Goldberg, Martha Arellano, Stephen A. Strickland, Karen Seiter, Gary Schiller, Elias Jabbour, Judy Chiao and William Plunkett

Conflict of Interest:

HK, GS and MW received research grants from Cyclacel. JH is an employee of Cyclacel. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ravandi F, Burnett AK, Agura ED, Kantarjian HM. Progress in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2007;110:1900–1910. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kantarjian H, O’Brien S, Cortes J, et al. Results of intensive chemotherapy in 998 patients age 65 years or older with acute myeloid leukemia or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome: predictive prognostic models for outcome. Cancer. 2006;106:1090–1098. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kantarjian H, Ravandi F, O’Brien S, et al. Intensive chemotherapy does not benefit most older patients (age 70 years or older) with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2010;116:4422–4429. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kantarjian H, O’Brien S. Questions regarding frontline therapy of acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2010;116(21):4896–4901. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kantarjian HM. Therapy for elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a problem in search of solutions. Cancer. 2007;109:1007–1010. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McHayleh W, Foon K, Redner R, et al. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin as firstline treatment in patients aged 70 years or older with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2010;116(12):3001–5. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kantarjian HM, Erba HP, Claxton D, et al. Phase II study of clofarabine monotherapy in previously untreated older patients with acute myeloid leukemia and unfavorable prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:549–555. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.3130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burnett AK, Russell NH, Kell J, et al. European development of clofarabine as treatment for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia considered unsuitable for intensive chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2389–2395. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas XG, Dmoszynska A, Wierzbowska A, et al. Results from a randomized phase III trial of decitabine versus supportive care or low - dose cytarabine for the treatment of older patients with newly diagnosed AML. ASCO. 2011 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.9429. Abstract 6504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, Hellstrom-Liindberg E, et al. Azacytidine prolongs overall survival compared with conventional care regimens in elderly patients with low bone marrow blast count acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:562–569. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.8329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuda J, Nakajima Y, Azuma A, et al. Nucleosides and nucleotides: 100. 2’-C-cyano-2’-deoxy-1-β-arabinofuranosylcytosine (CNDAC): Design of a potential mechanism-based DNA-strand-breaking anti-neoplastic nucleoside. J Med Chem. 1991;34:2917–2919. doi: 10.1021/jm00113a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanaoka K, Suzuki M, Kobayashi T, et al. Antitumor activity and novel DNA self-strand-breaking mechanisms of CNDAC (1-(2’-C-cyano-2’- deoxy-1-β-D-arabino-pentofuranosyl) cytosine and its N4-palmitoyl derivative (CS-682) Int J Cancer. 1999;82:226–236. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990719)82:2<226::aid-ijc13>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azuma A, Huang P, Matsuda A, et al. 2’-C-cyano-2’-deoxy-1-β-D-arabinopentofuranosyl cytosine: A novel anticancer nucleoside analog that causes both DNA strand breaks and G2 arrest. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:725–731. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.4.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Liu X, Matsuda A, Plunkett W. Repair of 2’-C-cyano-2’-deoxy-1- β-D-arabino-pentofuranosyl-cytosine-induced DNA single-strand breaks by transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3881–3889. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu X, Wang Y, Benaissa S, et al. Homologous recombination as a resistance mechanism to replication-induced double-strand breaks caused by the anti-leukemia agent, CNDAC. Blood. 2010;116(10):1737–1746. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-220376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kantarjian H, Garcia-Manero G, O’Brien S, et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of oral sapacitabine in patients with acute leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):285–291. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheson BD, Cassileth PA, Head DR, et al. Report of the National Cancer Institute-sponsored workshop on definitions of diagnosis and response in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:813–819. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.5.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheson BD, Greenberg PL, Bennett JM, et al. Clinical application and proposal for modification of the International Working Group (IWG) response criteria in myelodysplasia. Blood. 2006;108:419–425. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slovak ML, et al. Karyotypic analysis predicts outcome of preremission and postresmission therapy in adult myeloid leukemia: a Southwest Oncology Group/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study. Blood. 2000;96(13):4075–4083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burnett A, Wetzler M, Löwenberg B. Therapeutic Advances in acute myeloid leukemia. J of Clin Oncol. 2011;29(2):487–494. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cortes J, Foran J, Ghirdaladze D, DeVetten MP, Zodelava M, Holman P, Levis MJ, et al. AC220, a Potent, Selective, Second Generation FLT3 Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (RTK) Inhibitor, in a First-in-Human (FIH) Phase 1 AML Study. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts); Nov, 2009. p. 636. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas XG, Dmoszynska A, Wierzbowska A, et al. Results from a randomized phase III trial of decitabine versus supportive care or low - dose cytarabine for the treatment of older patients with newly diagnosed AML. ASCO Annual Meeting; 2011. Abstract 6054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faderl S, Ravandi F, Huang X, et al. A randomized study of clofarabine versus clofarabine plus low-dose cytarabine as front-line therapy for patients aged 60 years and older with acute myeloid leukemia and highrisk myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2008;112:1638–1645. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-124602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravandi F, Faderl S, Cortes J, et al. Phase 1/ 2 study of sapacitabine and decitabine administered sequentially in elderly patients with newly diagnosed AML. ASCO Annual Meeting; 2011. Abstract #81934. [Google Scholar]