Abstract

Amphetamine type stimulants (ATS) and ketamine have emerged as major drug problems in China, and chronic extensive exposure to these substances frequently co-occurs with psychiatric symptoms. This study compares the psychiatric symptoms of patients reporting ATS use only, ATS and ketamine use, or ketamine use only who were admitted to an inpatient psychiatry ward in Wuhan, China between 2010 and 2011. Data on 375 study participants collected during their ward admission and extracted from their clinical records included their socio-demographics, scores on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), and urine toxicology screens.

Results

The ketamine-only group had significantly lower total BPRS scores and significantly lower scores on Thinking Disorder, Activity, and Hostility-Suspicion BPRS subscales than the ATS-only and ATS+ketamine groups (p<0.001 for all comparisons). The ketamine-only group also had significantly higher scores on the subscales of Anxiety-Depression and Anergia. The ATS-only group had significantly higher scores on subscales of Thinking Disorder, Activity, and Hostility-Suspicion and significantly lower scores on Anxiety-Depression and Anergia subscales than the ketamine-only and ATS+ketamine groups (p<0.001 for all comparisons). A K-means cluster method identified three distinct clusters of patients based on the similarities of their BPRS subscale profiles, and the identified clusters differed markedly on the proportions of participants reporting different primary drugs of abuse. The study findings suggest that ketamine and ATS users present with different profiles of psychiatric symptoms at admission to inpatient treatment.

Keywords: Amphetamine type stimulants (ATS), ketamine, psychiatric symptoms

Objectives of the study and background

Amphetamine type stimulants (ATS) and ketamine have emerged as major drug problems in China and across Asia (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2012) and are associated with a broad range of psychiatric symptoms and disorders (Morgan and Curran, 2006; Srisurapanont et al., 2003). Repeated and extensive use of ATS may cause psychotic symptoms and is associated with mood disorders (Glasner-Edwards et al., 2008; Kalechstein et al., 2000; Zweben et al., 2004) and anxiety disorders (Conway et al., 2006). Ketamine users have been reported to present with symptoms that resemble both positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia (Javitt and Zukin, 1991; Li et al. 2011; Umbricht et al., 2000), as well as with cognitive impairments and depressive symptoms (Akiyama, 2006; Li et al. 2011. Chronic or heavy use of these substances may be associated with more severe psychiatric symptomatology necessitating inpatient treatment for some users (Akiyama, 2006; McKetin et al., 2006; Morgan and Curran, 2006; Morgan et al., 2010; Rawson and Ling, 2008; Smith et al., 2009; Ziedonis et al., 2003; Zweben et al., 2004).

In response to the increase in illicit ATS and ketamine use, as well as the increase in psychiatric disorders co-occurring with chronic use of these substances, and to address the increased need for hospital treatment associated with illicit ATS and ketamine use, Wuhan Mental Health Center in China developed a specialized inpatient psychiatric ward in July, 2007 exclusively for patients with psychotic disorders due to or concurrent with ATS or ketamine use. Although previous research supports an association between psychiatric symptoms and both ATS and ketamine use, it remains unclear whether specific psychiatric symptom presentations are more likely to co-occur with ATS as compared with ketamine use. In order to address these gaps in the research, the current study compares the psychiatric symptoms of patients reporting ATS use only, ATS and ketamine use, and ketamine use only who were admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit in Wuhan, China between 2010 and 2011.

Materials and methods

The current study used data extracted from medical records of inpatients admitted between January 2010 and December 2011 to a specialized inpatient psychiatric ward in Wuhan, China that exclusively treats patients with psychiatric disorders due to or concurrent with amphetamine type stimulants (ATS) or ketamine use disorders.

Street ATS drugs commonly used in China include crystalline methamphetamine (called “ice”) and a variety of pills (called “maguo”). Street “ice” and “maguo” are most frequently manufactured in clandestine, illegal laboratories, and contain various forms of amphetamine and/or methamphetamine derivatives (often <10% of amphetamine or methamphetamine content) mixed with other chemicals to boost the potency or subjective effects for the users. Street ketamine in China (called “K” or “K fen”) is relatively inexpensive as compared to other drugs including ATS. It is sold as a powder or liquid and can be injected, inhaled, consumed in drinks, or mixed with marijuana or tobacco. The primary sources of street Ketamine in China include diversion or theft of legal pharmaceuticals from medical or veterinary licit trade with some supplies also manufactured in clandestine laboratories (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2010). It is therefore believed that the purity and the quality of street ketamine is high (no research data available) contributing to its increasing popularity among drug users in China.

During the study period, 437 patients were admitted to the ward, some of whom were admitted multiple times, generating a total of 1,072 admissions during the two year study period. Admission criteria included: 1) diagnosis of psychotic disorder due to psychoactive substance use or abuse based on the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Version (ICD-10) (diagnostic code F 1x.5) and 2) primary ATS or ketamine use disorder without history of heroin, cocaine, or cannabis use. ICD-10 diagnoses were determined by trained attending psychiatrists during an initial admission interview.

Patients who reported a history of an alcohol abuse/dependence disorder or had a severe medical disorder were not included in the study sample. Of the 437 patients admitted during the study period, 51 were excluded due to alcohol dependence and 11 due to a severe medical condition (including hyperpyrexia, severe frequent micturition, severe trauma, coma, minimally conscious state, or delirium like conditions that precluded communication with the patient), resulting in the final sample of 375 participants. For patients with more than one hospital admission during this period, data from the first admission were used.

In addition to the clinical interviews and evaluations, all patients provided a urine sample on the second morning of admission as part of hospital procedures. Urine samples were tested for ATS (methamphetamine and amphetamine), ketamine, heroin, methadone, cocaine, cannabis, and benzodiazepines, using enzyme multiplied immunoassay technique (EMIT). The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (Overall and Gorham, 1962 was also administered during admission to evaluate the severity of psychiatric symptoms.

The BPRS is an 18-item scale assessing a broad range of psychiatric symptoms. The BPRS has been translated into Mandarin and validated (Hedlund and Vieweg, 1980; Lee et al., 1990) and is widely used in China. The BPRS is administered via interview by trained clinicians, and scores are determined through ratings of symptom severity on a 7 point Likert scale (1 – not present to 7 – extremely severe). Items are summed to produce a total score reflecting the overall severity of psychiatric symptoms. In addition to providing a total score, five symptom cluster scores are calculated: Anxiety-Depression (Somatic Concerns, Anxiety, Guilt, Depression), Anergia (Emotional Withdrawal, Motor Retardation, Blunted Affect, Disorientation), Thinking Disorder (Conceptual Disorganization, Grandiosity, Hallucinations, Unusual Thought Content), Activity (Tension, Mannerisms and Posturing, Excitement) and Hostility Suspicion (Hostility, Suspiciousness, Uncooperativeness) (Burger et al., 2000.

Demographic data on study participants, urine toxicology results and BPRS scores were extracted from patient records. No personally identifiable information on study participants was obtained. Study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Wuhan Mental Health Center.

Participants were divided into three study groups based on their drug use history: A) ATS-only (n=125), B) ketamine-only (n=38), and C) ATS+ketamine (n=212). Between group differences were analyzed using the χ2-test or Fisher’s Exact Probability Test for categorical variables and either Student’s t-test or ANOVA for continuous variables. We also used a K-means cluster method (Hartigan and Wong, 1979; MacQueen, 1967) to identify clusters of patients with similar symptom profiles on the five subscales of the BPRS. The K-means algorithm implemented in SPSS computationally searches for patterns among selected variables (BPRS subscale means) to uncover natural groupings among the study participants. In a stepwise, iterative manner, the algorithm initially assigns cluster membership using random groupings. The group means are then calculated and the cluster membership is evaluated and reassigned based on the distances between each participant data point and the group mean. This process is repeated until there are no changes in the cluster membership from the previous step/iteration. After identifying psychiatric symptom clusters using the K-means method, we compared study participants in each of the clusters based on primary drug of abuse.

Results

Participants were all Han Chinese and predominantly male (303/375, 81%). The majority of participants (301/375, 80%) reported less than 9 years of formal education, 155/375 (41%) were migrant workers, and 88/375 (24%) were unemployed. For the overall sample, the mean (SD) age was 30.2 (6.46) years. For males, the mean age was 30.8 (6.4) and for females it was 28.1 (6.5) years.

At admission, 86/125 (69%) of patients in the ATS-only group had an ATS positive urine result, 117/212 (55%) of patients in the ATS+ketamine group had an ATS positive and 98/212 (46%) had a ketamine positive urine result, and 17/38 (45%) of patients in the ketamine-only group had a ketamine positive urine result. No patients in the ATS-only group had a positive ketamine result and no patients in the ketamine-only group had a positive ATS urine result when they were admitted. The mean (SD) hospital stay for all study participants was 18.5 (SD= 9.7) days and the review of the medical records indicated that 367 had their discharge status indicating resolution or substantial amelioration of symptoms, 5 as improved, and 2 left before completing treatment.

The ketamine-only group had significantly lower total BPRS scores (40.13±7.68 vs. 46.50±6.24 and 47.28±7.56) and significantly lower scores on Thinking Disorder (1.74±0.57 vs. 3.15±0.7 and 2.74±0.84), Activity (1.61±0.32 vs. 3.06±0.68 and 2.81±0.76), and Hostility-Suspicion (3.02±0.77 vs. 4.81±0.95 and 4.30±1.03), subscales than the ATS-only and ATS+ketamine groups (p<0.001 for all comparisons). The ketamine-only group also had significantly higher scores on the subscales of Anxiety-Depression (2.91±0.49 vs. 1.53±0.35 and 2.30±1.00), and Anergia (1.91±0.61 vs. 1.06±0.11 and 1.46±0.46) than the ATS-only and ATS+ketamine groups (p<0.001 for all comparisons). The ATS-only group had significantly higher scores on subscales of Thinking Disorder, Activity, and Hostility-Suspicion and significantly lower scores on Anxiety-Depression and Anergia than the ketamine-only and ATS+ketamine groups (p<0.001 for all comparisons). The difference on the total BPRS scores was not statistically significant between the ATS-only and ATS+ketamine groups.

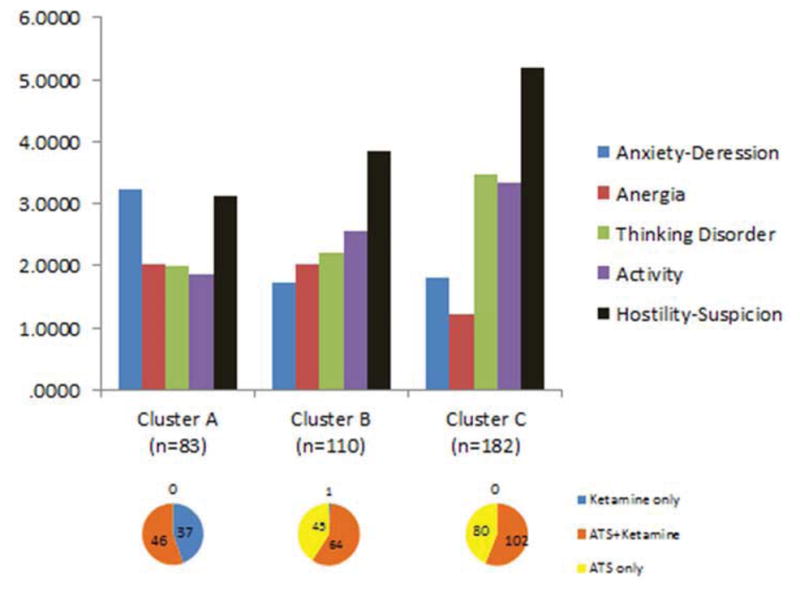

A K-means cluster method identified three distinct clusters of patients based on the similarities of their BPRS subscale profiles (see Figure 1). Cluster A (n=82), was characterized by higher scores on the Depression-Anxiety and Anergia and lower scores on Thinking Disorder, Activity, and Hostility-Suspicion than Clusters B (n=110) and C (n=182). Clusters B and C were characterized by somewhat similar symptom profiles, with Cluster C characterized by higher scores on Thinking Disorder, Activity, and Hostility-Suspicion and lower scores on Anergia than Cluster B.

Figure 1.

Profiles of BPRS subscale scores in each of the three identified clusters with the number of patients from each study group (primary drug category) represented by each of the three clusters.

Crosstabulation of the three identified clusters against the three study groups (based on primary drug of abuse) showed a markedly different distribution of the primary drug of abuse between the Cluster A and Clusters B and C. Cluster A contained virtually all of the ketamine-only patients (37/38 or 97%) and no ATS-only patients. Clusters B and C contained similar proportions of ATS-only and ATS+ ketamine patients, with only one ketamine-only patient in Cluster B.

Discussion

Findings of the current study suggest that patients who primarily use ketamine have a significantly different presentation of psychiatric symptoms than patients who use only ATS or ATS + ketamine. Ketamine-only patients presented with lower severity of symptoms in Thinking Disorder, Activity, and Hostility-Suspicion, than patients who used only ATS or ATS+ketamine. Additionally, ketamine-only patients demonstrated a higher severity of symptoms in Anxiety-Depression and Anergia. Interestingly, the effects of using ATS and ketamine do not seem to be additive. Patients using both ATS and ketamine presented with a moderate severity level of symptoms on all BPRS subscales.

Study findings are consistent with earlier reports and may reflect differences in underlying neural mechanisms specific to ketamine and ATS. Amphetamine and methamphetamine increase dopamine release into the synaptic cleft and also alter the dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin reuptake transporters, leading to prolongation of the effects of dopamine (Fleckenstein et al., 2007; Heal et al., 2013). Acute effects of ATS include promoting wakefulness; decreasing fatigue; inducing overall stimulation and euphoria; and increasing concentration, focus, alertness, and libido (Cruickshank and Dyer, 2009). ATS use, particularly at higher doses or following repeated or chronic use, is also associated with paranoia or thought disorders (Srisurapanont et al., 2003). Current study findings are consistent with these previous reports and show a higher severity of hostility, suspicion, and thinking disorder symptoms among ATS users.

Ketamine, a potent N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist, primarily affects the actions of glutamate and excitatory neurotransmitters, but it also interacts with dopamine receptors and acts as a noradrenergic and serotonergic uptake inhibitor (Orser et al., 1997; Quibell et al., 2011). The effects of ketamine are dose-dependent. At higher doses, ketamine is a “dissociative” anesthetic (producing a dissociation between the thalamocortical and limbic systems of the central nervous system (White et al., 1982). Recent studies suggest that at lower doses ketamine has powerful antidepressant effects (Sanacora et al., 2008), but chronic and extensive ketamine use is associated with elevated depression and anxiety symptoms (Morgan and Curran, 2011). Consistent with these findings in chronic ketamine users, ketamine users in this study had a higher severity of anxiety, depression, and anergia symptoms compared to ATS users.

Despite their potential for therapeutic use, illicit ATS and ketamine use have increased rapidly in China in recent years, and the severe, adverse psychiatric effects of their misuse necessitated the creation of specialized psychiatric wards for patients with these psychiatric presentations. Further research is needed to better inform our understanding of the distinct ways that ketamine and ATS are related to psychiatric symptoms and to better inform clinical practice for patients with psychiatric symptoms co-occurring with ATS and ketamine use.

Study limitations include evaluation of a sample of patients presenting for admission at a single hospital (potentially affecting generalizability of the findings) and the relatively small size of the ketamine-only group compared to the two other groups. The cross-sectional study design precludes evaluation of the causal nature of the relationship between psychiatric symptoms and ketamine or ATS use. Furthermore, the diagnosis and subsequent classification of patients into the study groups was based primarily on self-report and limited collateral information obtained from patients’ family members, and we did not collect detailed information on quantity, frequency, pattern, or duration of drug use by study participants. Despite reliance on self-report data, the findings that no ATS-only patients tested positive at admission for ketamine and no ketamine-only patients tested positive for ATS support the validity of this classification.

Overall, current findings suggest that patients who use only ketamine have less severe thought disorder symptoms and more severe depression and anxiety symptoms than patients who use only ATS or ATS+ketamine. There are important clinical implications of the study. Clinicians should be aware that certain psychiatric symptoms are more likely to occur with use of particular substances in order to deliver effective treatments that address psychiatric symptoms as well as substance use disorders. The study findings are consistent with current practice recommendations that a period of abstinence and observation during abstinence is important prior to initiating pharmacological treatments, because symptoms often remit following cessation of drug use.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akiyama K. Longitudinal clinical course following pharmacological treatment of methamphetamine psychosis which persists after long-term abstinence. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1074:125–134. doi: 10.1196/annals.1369.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger GK, Calsyn RJ, Morse GA, Klinkenberg WD. Prototypical profiles of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2000;75:373–386. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7503_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruickshank CC, Dyer KR. A review of clinical pharmacology of methamphetamine. Addiction. 2009;104:1085–1099. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67:247–257. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleckenstein AE, Volz TJ, Riddle EL, Gibb JW, Hanson GR. New insights into the mechanism of action of amphetamines. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2007;47:681–698. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasner-Edwards S, Mooney LJ, Marinelli-Casey P, Hillhouse M, Ang A, Rawson R. Identifying methamphetamine users at risk for major depressive disorder: findings from the methamphetamine treatment project at three-year follow-up. American Journal on Addictions. 2008;17:99–102. doi: 10.1080/10550490701861110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartigan JA, Wong MA. Algorithm AS 136: A K-means clustering algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series C (Applied Statistics) 1979;28:100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Heal DJ, Smith SL, Gosden J, Nutt DJ. Amphetamine, past and present – a pharmacological and clinical perspective. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2013;27:479–496. doi: 10.1177/0269881113482532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund JL, Vieweg BW. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): a comprehensive review. Journal of Operational Psychiatry. 1980;11:48–62. [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC, Zukin SR. Recent advances in the phencyclidine model of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:1301–1308. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.10.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalechstein AD, Newton TF, Longshore D, Anglin MD, van Gorp WG, Gawin FH. Psychiatric comorbidity of methamphetamine dependence in a forensic sample. Journal of Neuropsychiatry & Clinical Neurosciences. 2000;12:480–484. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.4.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MB, Lee YJ, Yen LL, Lin MH, Lue BH. Reliability and validity of using a Brief Psychiatric Symptom Rating Scale in clinical practice. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 1990;89:1081–1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JH, Vicknasigam B, Cheung YW, Zhou W, Nurhidayat AW, Jarlais DCD, Schottenfeld R. To use or not to use: an update on licit and illicit ketamine use. Journal of Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation. 2011;2:11–20. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S15458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen JB. Some Methods for classification and Analysis of Multivariate Observations, Proceedings of 5-th Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability. Berkeley, University of California Press. 1967;1:281–297. [Google Scholar]

- McKetin R, McLaren J, Lubman DI, Hides L. The prevalence of psychotic symptoms among methamphetamine users. Addiction. 2006;101:1473–1478. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CJ, Curran HV. Acute and chronic effects of ketamine upon human memory: A review. Psychopharmacology. 2006;188:408–424. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0572-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CJ, Curran HV Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs. Ketamine use: a review. Addiction. 2011;107:27–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CJ, Muetzelfeldt L, Curran HV. Consequences of chronic ketamine self-administration upon neurocognitive function and psychological wellbeing: a 1-year longitudinal study. Addiction. 2010;105:121–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- Orser BA, Pennefather PS, MacDonald JF. Multiple mechanisms of ketamine blockade of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:903–917. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199704000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quibell R, Prommer EE, Mihalyo M, Twycross R, Wilcock A. Ketamine. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2011;41:640–649. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson RA, Ling W. Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment. American psychiatric publishing; Washington DC: 2008. Clinical management: methamphetamine. [Google Scholar]

- Sanacora G, Zarate CA, Krystal JH, Manji HK. Targeting the glutamatergic system to develop novel, improved therapeutics for mood disorders. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2008;7:426–437. doi: 10.1038/nrd2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Thirthalli J, Abdallah AB, Murray RM, Cottler LB. Prevalence of psychotic symptoms in substance users: a comparison across substances. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2009;50:245–50. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srisurapanont M, Ali R, Marsden J, Sunga A, Wada K, Monteiro M. Psychotic symptoms in methamphetamine psychotic in-patients. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;6:347–52. doi: 10.1017/S1461145703003675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Patterns and trends of amphetamine-type stimulants and other drugs - Asia and the pacific. 2012 http://wwwunodcorg/documents/scientific/Patterns_and_Trends_of_Amphetaime-Type_Stimulants_and_Other_Drugs_-_Asia_and_the_Pacific_-_2012pdf.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report. 2010 http://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr/WDR_2010/World_Drug_Report_2010_lo-res.pdf.

- Umbricht D, Schmid L, Koller R, Vollenweider FX, Hell D, Javitt DC. Ketamine-induced deficits in auditory and visual context-dependent processing in healthy volunteers: implications for models of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:1139–1147. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.12.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White PF, Way WL, Trevor AJ. Ketamine—its pharmacology and therapeutic uses. Anesthesiology. 1982;56:119–136. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziedonis D, Steinberg ML, Smelson D, Wyatt S. Principals of Addiction Medicine. American Society of Addiction Medicine; Maryland: 2003. Co-occurring addictive and psychotic disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Zweben JE, Cohen JB, Christian D, Galloway GP, Salinardi M, Parent D, Iguchi M. Psychiatric symptoms in methamphetamine users. American Journal on Addictions. 2004;13:181–190. doi: 10.1080/10550490490436055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]