Abstract

A small DNA fragment containing the high-frequency initiation region (IR) ori-β from the hamster dihydrofolate reductase locus functions as an independent replicator in ectopic locations in both hamster and human cells. Conversely, a fragment of the human lamin B2 locus containing the previously mapped IR serves as an independent replicator at ectopic chromosomal sites in hamster cells. At least four defined sequence elements are specifically required for full activity of ectopic ori-β in hamster cells. These include an AT-rich element, a 4-bp sequence located within the mapped IR, a region of intrinsically bent DNA located between these two elements, and a RIP60 protein binding site adjacent to the bent region. The ori-β AT-rich element is critical for initiation activity in human, as well as hamster, cells and can be functionally substituted for by an AT-rich region from the human lamin B2 IR that differs in nucleotide sequence and length. Taken together, the results demonstrate that two mammalian replicators can be activated at ectopic sites in chromosomes of another mammal and lead us to speculate that they may share functionally related elements.

The replicon model, proposed 40 years ago as a simple mechanism to account for the control of initiation of DNA replication in bacteria, has proven a remarkably durable guide for investigations of replication control. In its simplest form, it proposed a cis-acting element, the replicator, and a trans-acting initiator factor that recognizes the replicator and activates replication there (36). Many replication origins in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae conform fairly well to the replicon model. In S. cerevisiae, autonomously replicating sequence (ARS) elements serve as replicators on episomes and in chromosomes (9, 10). The ARS elements are composed of an ARS consensus sequence, which is recognized by the origin recognition complex (ORC), and auxiliary elements that enhance initiation activity by binding to transcription factors and regulating chromatin structure (9, 48, 58, 63). Initiation of leading strand synthesis occurs directly adjacent to the ARS consensus sequence in the replicator ARS1 (12, 13). Replication in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe is also controlled by ORC recognition of replicators, but the replicators are larger than in S. cerevisiae and the sequences recognized consist of AT-rich tracts rather than a short consensus sequence (19, 20, 39, 41, 42, 54, 59, 60).

Biochemical and physical mapping of origins of replication in mammalian chromosomes suggests that replicators may specify start sites of replication. For example, start sites are usually inherited from mother cell to daughter cell and exhibit the same timing of origin firing in successive cell division cycles (reviewed in references 14, 22, 23, 28, 31, 32, 51, 56, and 62). Given the conservation of ORC from yeast to mammals, it is reasonable to hypothesize that ORC recognizes replicators in mammalian chromosomes. Consistent with this idea, ORC resides at several metazoan origins, including Sciara coprophila oriII/9A (11), Drosophila melanogaster ACE3 (7, 8), origins upstream from the human MCM4 (45) and TOP1 genes (38), and at the 3′ end of the human lamin B2 gene (1). However, identification of specific sequence elements in mapped mammalian origins that ORC could recognize has been difficult so far (9, 14, 31, 61).

As an alternative to mapping origins, genetic assays have been devised to test directly for replicator activity of DNA fragments from mammalian chromosomes. In these assays, local replication initiation activity in the DNA fragment is measured after it has been placed at ectopic chromosomal locations in mammalian cells. One strategy involves integration of the putative replicator into a previously defined locus using FLP- or Cre-mediated recombination and analysis of a cloned cell population (see, e.g., references 4 and 50). Another strategy uses nonspecific integration of a putative replicator into multiple ectopic sites in chromosomal DNA followed by analysis of uncloned cell pools or cloned lines (5). Thus, both strategies are fundamentally analogous to the stably integrated reporter gene constructs used successfully in studies of cis-acting sequence elements that control gene expression in eukaryotic chromosomes (reviewed in references 34 and 46).

Using these genetic assays, defined DNA fragments of several kilobase pairs in length containing the human β-globin (4), the human c-myc (50, 49), and hamster dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) ori-β (5) initiation regions (IRs) have been demonstrated to serve as replicators when placed at ectopic chromosomal locations. Initial mutational analyses of these replicators also revealed that multiple defined sequence elements are required for their initiation activity. However, consensus DNA sequences shared among these replicators have not been identified. Given the requirement for defined sequence elements in these mammalian replicators, it is possible that some of these elements may substitute functionally for each other even though they lack a consensus sequence, a possibility that we have explored in this report.

Toward this end, we extend our previous work by first showing that the DHFR ori-β replicator directs robust initiation in ectopic chromosomal locations in both hamster and human cell lines and then identifying several new sequence elements that are specifically required for ori-β replicator activity. In addition, we present evidence that the human lamin B2 origin directs initiation at ectopic locations in hamster chromosomes. Lastly, we demonstrate that an AT-rich element from the human lamin B2 origin is able to substitute for an essential AT-rich element in the hamster ori-β origin, suggesting that some defined functional elements may be conserved among mammalian replicators.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

DR12 cells, a CHOK1 derivative lacking both alleles of the entire DHFR locus (37), were grown in Ham's F-12 medium (Gibco Invitrogen Co., Carlsbad, Calif.) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, Ga.) at 37°C with 4% CO2. HeLa (29) and HCT116 (15, 16) cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco Invitrogen Co.) supplemented with 10% FCS at 37°C with 10% CO2.

Plasmid construction.

The plasmid pMCD, containing DHFR ori-β on a 5.8-kb BamHI-KpnI fragment (GenBank accession no. Y09885) in pUC19, was the kind gift of Nick Heintz (18). The plasmid pDP17, containing approximately 13.5 kb of the human lamin B2 origin (GenBank accession no. M94363) was the kind gift of Mauro Giacca. Plasmid pLam was created by subcloning a 6.5-kb BamHI-SalI fragment from pDP17 into the BamHI-SalI site of pUC19. Mutant pMCDΔAT was described previously (5). Mutant pATrep was created by swapping the 344-bp SphI-EcoRV fragment of pMCD for a 297-bp SphI-PvuII fragment from pSV2neo (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.). Mutant pLamRep was created by swapping the 344-bp SphI-EcoRV fragment of pMCD for a 224-bp fragment of the lamin B2 origin. The 224-bp fragment was generated by PCR amplification of pDP17 using primers that contained either an SphI or an EcoRV recognition sequence on the 5′ end (5′-CAAAGCATGCAGATGCATGCCTAGCGTGTTC and 5′ CTGTGATATCTAGCTACACTAGCCAGTGACCTTTTTCCT). The PCR products were digested with SphI and EcoRV and cloned into the pMCD SphI-EcoRV vector fragment. Deletion mutant pAKO was described previously (5). Substitution mutant pΔ4rep was created by PCR amplification using mutagenic primers (5′-GATTCACTGCATGCTTTCTTTCC and 5′-GGAAAGAAACATGCAGTGAATC) to replace the 4-bp sequence GGCC with CATG. Mutant pBENDx was created by using PCR and mutagenic primers (5′-GAGTCAGCGCATGGGCGCGCAAGACTAGCGCCTAAGTCTCATC and 5′-GCCCATGCGCTGACTCGCGCCTAGTTTCGCGATTATTATTATTAG) to replace the five tracts of A and T which contribute to the bend (18) with G and C (see Fig. 3B). Mutant pRIP DSx was created using PCR and mutagenic primers (5′-CTAGTTTTTTTATCGATCTCGAGGGTTCAAATTAGG and 5′-CCTAATTTGAACCCTCGAGATCGATAAAAAAACTAG) to replace the RIP60 consensus binding sequence (17) with other sequences (see Fig. 4B). The nucleotide position and size of each mutation are provided in Table 1.

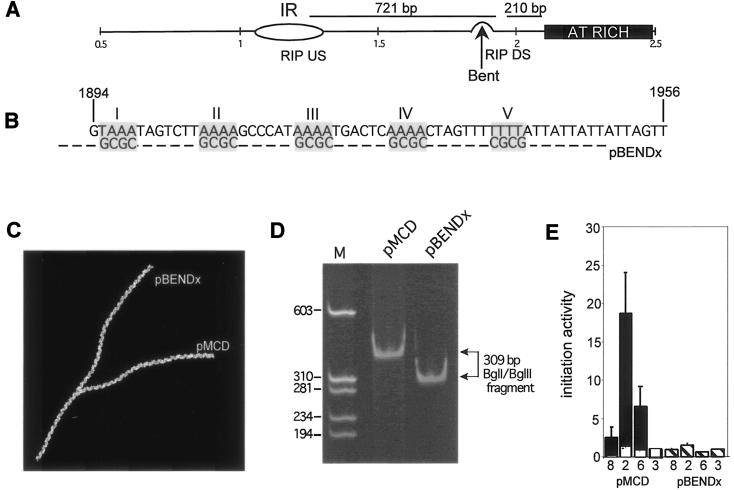

FIG. 3.

Initiation activity at ectopic ori-β requires DNA sequences in an intrinsically bent element. (A) Location of a bent DNA region in the DHFR ori-β IR in relation to the start site of replication (IR) and the AT-rich element. Nucleotide numbers in kilobases (GenBank accession number Y09885) are indicated below the diagram. Upstream and downstream consensus binding sites for the RIP60 protein in vitro are indicated (21). (B) Sequence of the bent DNA region of the DHFR ori-β IR. Roman numerals indicate the five A or T tracts (shaded boxes) that contribute to DNA bending (18). Each of the five tracts was mutated (pBENDx) to alternating G and C residues to preclude bending (lower sequence in shaded box). Nucleotide numbers correspond to GenBank accession number Y09885. (C) Predicted DNA structure of a 309-bp BglI-BglII DNA fragment, containing the bent DNA region near the middle of the fragment, based on computer analysis of the DNA sequence (Model.it software; ICGEBnet). (D) Plasmid constructs containing either the wild-type (pMCD) or mutated (pBENDx) bend region were digested with BglI and BglII to release a 309-bp DNA fragment containing with the wild-type or mutated bent region near the middle of the fragment. The electrophoretic mobility of the 309-bp fragment was analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and visualized with ethidium bromide staining. M indicates marker DNA fragments with the indicated sizes (in base pairs). (E) The abundance of nascent DNA from pools of pBENDx-transfected DR12 cells from three independent transfection experiments was quantitatively measured, and the average initiation activity from the three separate experiments is shown. For comparison, the average initiation activity of the wild-type 5.8-kb DHFR ori-β fragment (black bars) and background activity for the assay system (white bars) are shown. Error bars, SEM.

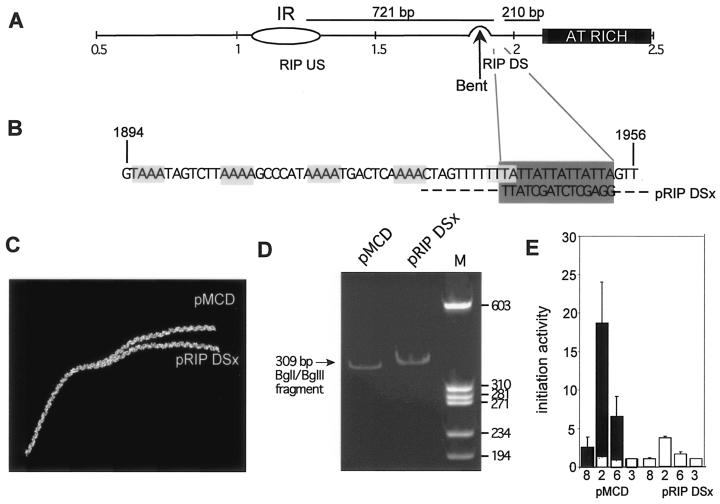

FIG. 4.

Initiation activity at ectopic ori-β is adversely affected by mutation of a RIP60 consensus binding sequence. (A) Location of RIP60 binding sites (21) in the DHFR ori-β IR in relation to the bent DNA region, the start site of replication (IR) and the AT-rich element. Nucleotide numbers in kilobases (GenBank accession number Y09885) are indicated below the diagram. (B) Sequence of the downstream RIP60 site is indicated in the dark gray shaded box. The five A or T tracts that contribute to DNA bending are indicated in the light gray shaded boxes (18). The downstream RIP60 site was mutated (pRIP DSx) without disturbing the overlapping nucleotide sequence in the fifth tract that contributes to the bend. Nucleotide numbers correspond to GenBank accession number Y09985. (C) Predicted DNA structure of a 309-bp BglI-BglII DNA fragment containing the bent DNA region and the RIP60 binding site in pMCD and pRIP DSx based on computer analysis of the DNA sequence (Model.it software; ICGEBnet). (D) Plasmid constructs containing either the wild-type (pMCD) or mutated (pRIP DSx) bend region were digested with BldI and BglII to release a 309-bp DNA fragment containing the wild-type or mutated region near the middle of the fragment. The electrophoretic mobility of the 309-bp fragment was analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and visualized with ethidium bromide staining. Lane M, marker DNA fragments (sizes indicated at right in base pairs). (E) The abundance of nascent DNA from pools of pRIP DSx-transfected DR12 cells from three independent transfection experiments was quantitatively measured, and the average initiation activity from the three experiments is shown. For comparison, the average initiation activity of the wild-type 5.8-kb DHFR ori-β fragment (black bars) and background activity for the assay system (white bars) is shown. Error bars, SEM.

TABLE 1.

Nucleotide positions of deletion and substitution mutations in the DHFR ori-β ectopic fragment

| Mutant | Nucleotide position in ori-βa | Replacement DNAb | Accession no.c | Fragment sized (bp) (type) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pMCDΔAT | 2163 | 344 (deletion) | ||

| pATrep | 2163 | 2208 | U02434 | 297 (replacement) |

| pAKO | 1127 | 4 (deletion) | ||

| pΔ4rep | 1127 | 4 (replacement)e | ||

| pBENDx | 1895 | 20 (replacement)f | ||

| pRIP DSx | 1943 | 9 (replacement)g | ||

| pLamRep | 2163 | 3880 | M94363 | 224 (replacement) |

| pMCDΔTR | 686 | 263 (deletion) | ||

| pMCDΔDNR | 4219 | 235 (deletion) |

The nucleotide position refers to the first nucleotide of either the replacement or deletion mutation in the DHFR ori-β initiation region. The BamHI recognition sequence in the DHFR ori-β fragment pMCD is defined as position 1 (GenBank accession no. Y09885).

The nucleotide position refers to the first nucleotide of the replacement DNA according to the GenBank sequence information for each replacement. The HpaI recognition sequence in the lamin B2 origin fragment is defined as position 1 (GenBank accession no. M94363).

The accession number refers to the source of the sequence information of the replacement DNA where appropriate.

The fragment size of the DNA deletion or replacement.

See Fig. 2B for sequence.

See Fig. 3B for sequence.

See Fig. 4B for sequence.

Transfection.

Four micrograms of pMCD DNA or a mutant derivative, mixed in a 3:1 molar ratio with PvuI-linearized pSV2neo DNA, were electroporated into 5 × 106 DR12, HeLa, or HCT116 cells using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser at 360 V and 650 μF. The transfection conditions were chosen so that the average copy number of ectopic ori-β fragments per cell in the pool of DR12 or human cells would mimic that of the endogenous ori-β in CHOK1 DNA. Similarly, 4 μg of pLam DNA, mixed in a 3:1 molar ratio with PvuI-linearized pSV2neo DNA, were electroporated into 5 × 106 DR12 cells. Cells were plated in 75-cm2 tissue culture flasks. After 24 h, the medium was replaced with Ham's F-12 medium supplemented with 10% FCS and G418 (0.5 mg/ml; Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.) for DR12 cells or Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FCS and G418 (0.5 mg/ml) for HeLa and HCT116 cells. After 4 weeks of growth under selection, exponentially proliferating cells from four 150-cm2 flasks grown to 70% confluency (2 × 107 to 4 × 107 DR12 cells, 0.7 × 108 to 1 × 108 HeLa or HCT116 cells) were harvested, and total DNA was isolated and analyzed as described below. Under these transfection conditions, the average number of copies of exogenous DHFR ori-β or exogenous lamin B2 integrated per cell in pools of cells was determined as described previously (5) and found to be approximately two copies (5; data not shown). The integration pattern of ectopic ori-β was analyzed by Southern blotting after BamHI-KpnI digestion of total genomic DNA from uncloned pools of pMCD-transfected cells. Based on comparison with the hybridization signal from an endogenous locus (GNAI3) (6), between a third and a half of the integrated ori-β sequence detected with two ori-β probes migrated as a band at the position of the 5.8-kb full-length sequence. The rest of the ori-β sequences appeared in a smear distributed over the entire lane (S. Gray and E. Fanning, unpublished data). These preliminary observations are consistent with the notion that pMCD DNA was broken randomly and integrated in chromosomal DNA (5).

DNA isolation and gradient centrifugation.

For each experiment with each construct, total genomic DNA was isolated from uncloned stably transfected cell pools (5). Cells were collected as a loose pellet in a 50-ml conical centrifuge tube, washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and resuspended in 6 ml of 400 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]-60 mM EDTA-150 mM NaCl-1% sodium dodecyl sulfate with two sharp flicks of the wrist. The suspension was poured into a 15-ml polypropylene centrifuge tube and mixed with 1.5 ml of 5 M sodium perchlorate by rotating on a horizontal mechanical rotator for 15 min at room temperature. After incubation at 65°C for 25 min, 5.5 ml of cold chloroform (chilled at −20°C) was added to the tube and mixed for 10 min by rotation at room temperature. The tube was centrifuged at 1,400 × g for 5 min, and the aqueous phase containing nucleic acid (top) was carefully transferred to a fresh 50-ml tube. Two volumes of cold ethanol were added to the aqueous phase and the tube was gently inverted to facilitate mixing. The insoluble DNA floating in the tube was lifted out on a pipette tip and air-dried in a 2-ml microcentrifuge tube. It was redissolved in 1 to 2 ml of sterile TE by mixing overnight on a rotator. No RNase treatment was performed. Each experiment yielded 400 to 700 μg of total nucleic acid from DR12 and 1 to 2 mg from HeLa or HCT116 cells.

For each transfectant, 400 to 500 μg of total nucleic acid in 1 ml of TE (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 1 mM EDTA) was heat denatured at 100°C for 10 min, followed by a 10-min incubation in ice-water. The entire sample was then immediately loaded onto a 5-to-30% linear neutral sucrose gradient and centrifuged at 26,000 rpm (Sorvall AH-629 rotor) for 17 h at 20°C. As size markers, 50 μg of pMUT8-2, digested with KpnI and NdeI to produce fragment sizes of 921 and 2,972 bp, and 50 μg of pKl26, digested with StuI and BglII to produce fragment sizes of 1,636 and 4,338 bp, were loaded on a separate sucrose gradient and centrifuged concurrently with each genomic DNA sample. Fractions of 1 ml were collected, and a 50-μl aliquot of each marker fraction was analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel at 200 mA for 2 h followed by ethidium bromide staining. A single fraction (containing an average of 3.55 μg in 27 experiments) enriched in nascent DNA corresponding to a length of ca. 0.4 to 2.0 kb (hereafter termed the nascent fraction) was dialyzed against TE and used as a template for all PCR amplifications in that experiment.

To monitor the composition of the nucleic acid in the nascent fraction of a typical experiment, a 500-μl sample of the fraction was precipitated with 1/10 volume of 3 M sodium acetate and an equal volume of isopropanol. The precipitate was redissolved in 30 μl of TE. Ten microliters of this material was digested with RNase A (40 μg/ml; BD Biosciences, Palo Alto, Calif.) for 1 h at 37°C. Another 10 μl was digested with 10 U of mung bean nuclease (Promega, Madison, Wis.) at 37°C for 15 min. Both samples and 10 μl of the undigested starting material were then analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Construction of PCR competitive templates.

Except for the lamin B2 competitors, competitors were previously described (5). The competitors for the lamin B2 origin were constructed in the same manner using the following primers (55): ComB48DX, 5′-GTCGACGGATCCCTGCAGGTCAGAGGCAGAACCTAAAATC; ComB48SX, 5′-ACCTGCAGGGATCCGTCGACAGTTTATTCCTGAGGGGAAG; BEComDX, 5′-ACCTGCAGGGATCCGTCGACAGCTCCCTGACCTGTGTAC; and BEComSX, 5′-GTCGACGGATCCCTGCAGGTCACGCCAGGGCCTTGAGG.

PCR-based nascent-strand abundance assay.

The competitive PCR nascent-strand abundance assay was performed as previously described using primer sets 8, 2, 6, and 3 on DHFR ori-β (Fig. 1A) (5, 27, 44, 55) and primer sets LO, BE, and B48 (30) on the human lamin B2 origin and lamin B2 replacement constructs. In our hands, primer pair B48 yielded specific amplification products with lamin B2 templates only in the hamster cell background (not shown); hence, the flanking primer pair LO was used in the human background. The sequences and map positions of the primers are listed in Table 2. Each PCR mixture included the corresponding competitor plasmid DNA, which had been precalibrated against 20 ng of total genomic DNA from asynchronously growing CHOK1, HeLa, or HCT116 cells (5). Amplification reaction mixtures with each primer set contained increasing amounts of the nascent fraction and a constant amount of the corresponding competitor DNA. PCR was carried out in a Perkin-Elmer 4800 thermal cycler. For the ori-β primers, the reaction conditions were 50 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. For the lamin B2 primers, the reaction conditions were 50 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Amplification products were resolved by 7% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, stained with ethidium bromide, and quantified by densitometry (IPLab Gel software; Signal Analytics Corporation, Vienna, Va.).

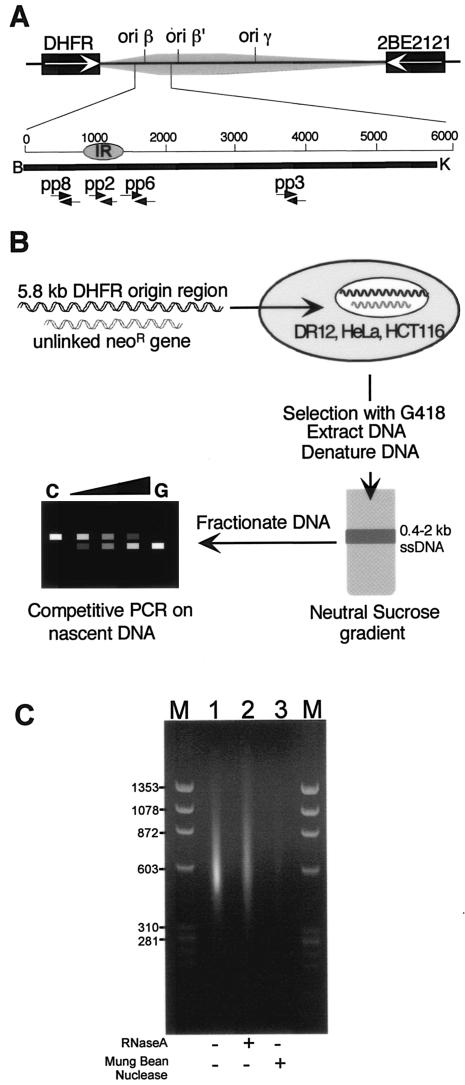

FIG. 1.

Strategy to genetically define elements of the DHFR ori-β replicator in ectopic chromosomal locations. (A) Features of the endogenous DHFR ori-β IR. Preferred start sites of DNA replication (ori-β, ori-β′, and ori-γ), contained within a 55-kb zone of less-frequent initiation events (shaded area) are indicated (see references 24, 40, 52, and 55 and references therein). The 5.8-kb DNA fragment of the DHFR ori-β region, extending from the BamHI (B) (nucleotide position 1 [GenBank accession number Y09885]) to the KpnI (K) recognition site is indicated (heavy black bar). Arrows denote the positions of the primers used in the PCR-based nascent-strand abundance assay (Table 2), which correspond to primer pairs used in previous mapping studies (5, 55). (B) Strategy for quantitating initiation occurring in exogenous DHFR ori-β fragments in ectopic chromosomal locations in hamster and human cells. A 5.8-kb wild-type or mutated DHFR ori-β fragment was coelectroporated with an unlinked neomycin resistance gene into DR12, HeLa, or HCT116 cells. After selection and expansion of stable transformants in the presence of G418, total DNA was isolated from uncloned cell pools, heat denatured, and size fractionated by velocity sedimentation. A fraction containing DNA with a length of 0.4 to 2 kb, enriched in nascent DNA, was used to quantify the abundance of ori-β target sequences in the fraction by competitive PCR. (C) Samples of total nucleic acid from the chosen sucrose gradient fraction were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis either directly (lane 1), or after treatment with RNase A (lane 2) or mung bean nuclease (lane 3). M indicates marker DNA fragments of the indicated sizes (in base pairs).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primer sequences for amplification of target sequences in the DHFR ori-β and human lamin B2 origins

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Position |

|---|---|---|

| 8SX | CTCTCTCATAGTTCTCAGGC | 470-489a |

| 8DX | GTCCTCGGTATTAGTTCTCC | 651-670a |

| 2SX | GTCCCTGCCTCAAAACACAA | 1070-1089a |

| 2DX | CCTTCATGCTGACATTTGTC | 1329-1348a |

| 6SX | AACTGGCTTCCCAAGAAATT | 1517-1536a |

| 6DX | AACCTCTGAACTGTAAGCTG | 1666-1685a |

| 3SX | GGACACTAAGTCTAGGTACTACA | 3882-3904a |

| 3DX | GCTGGGATAAGTTGAAATCC | 4121-4140a |

| B48DX | AGATGCATGCCTAGCGTGTTC | 3880-3900b |

| B48SX | TAGCTACACTAGCCAGTGACCT | 4083-4104b |

| LO-F | GCGTCACAGCACAACCTGC | 3795-3813b |

| LO-R | TCTTTCTTAGACATCCGCTTC | 4041-4061b |

| BEDX | GGCAATAGCTCACCGTTTAC | 2308-2327b |

| BESX | ACTTTCTGAAGGAGGCTCTG | 2481-2500b |

Nucleotide position relative to the BamHI recognition sequence in the DHFR ori-β fragment pMCD, defined as position 1 (GenBank accession no. Y09885). Primer sets 8, 2, 6, and 3 are identical to those used elsewhere (55).

Nucleotide position relative to the HpaI recognition sequence in the lamin B2 origin fragment, defined as position 1 (GenBank accession no. M94363).

For each transfection experiment, PCR was performed at least twice with each primer set to determine the equivalence point for target DNA in the nascent fraction and competitor templates. The ratio of PCR amplification products from nascent-fraction template to those from competitor template was plotted against the volume of input nascent-fraction template. The equation of the slope of this line (R2 values greater than 0.97), along with the known number of molecules per microliter of calibrated competitor, was used to calculate the number of molecules per microliter of target in the nascent fraction for each primer set. Since the size of each amplification product is known and can be used to calculate grams per mole base pairs, the number of molecules per microliter for each amplification product can be converted into a DNA concentration. Thus, the concentration of target molecules for each primer pair in the nascent fraction can be calculated. This concentration can then be expressed relative to the concentration of total nucleic acid in the nascent fraction determined by absorbance at 260 nm, yielding a relative molecular abundance of each target DNA, hereafter termed the abundance. This value varies between experiments and should not be misconstrued as an absolute determination of the amount of target DNA in a certain amount of purified nascent DNA; rather, it is an empirical value intended to facilitate comparison of the amounts of different targets in the same fraction of DNA enriched in nascent strands (see below).

To facilitate comparison between independent transfection experiments with the same ori-β construct, the abundance of target sequences for each primer pair in each experiment was expressed relative to the abundance of the target sequences for the distal primer pair 3 in the same experiment (termed initiation activity). For the lamin B2 origin, the abundance of target sequences for each primer pair in each experiment was expressed relative to the abundance of the target sequences for the distal primer pair BE in the same experiment. Therefore, the nucleic acid concentration of the nascent fraction in each experiment only impacts abundance and not the initiation activity, since it cancels out when the initiation activity is calculated for each experiment. Standard error of the mean (SEM) was chosen to express the reliability of the mean (67).

RESULTS

Specific sequence elements are required for full initiation activity at ectopic ori-β.

We have previously shown that a 5.8-kb DNA fragment containing the DHFR ori-β IR is able to support initiation in ectopic chromosomal locations using a PCR-based nascent-strand abundance assay (Fig. 1) (5). Briefly, a DNA fragment containing the ori-β IR was cotransfected with a neomycin resistance gene into a cell line lacking any endogenous ori-β DNA (Fig. 1B). Total genomic DNA was extracted from stable cell pools, redissolved, denatured, and fractionated on a neutral sucrose gradient to enrich for single-stranded DNA of 0.4 to 2 kb in length (Fig. 1C, lane 1). To examine the amount of residual RNA in the nascent fraction, the material was treated with an amount of RNase A shown to be sufficient to digest at least 5 μg of RNA in 30 min (not shown). As seen in Fig. 1C, a slight reduction in the amount of nucleic acid fragments was observed after RNase digestion (compare lanes 1 and 2), consistent with the notion that most of the material was DNA of the expected length. To assess whether the nascent fraction remained single-stranded through the isolation process, it was treated with single-stranded-DNA-specific mung bean nuclease. Most of the nucleic acid present in the fraction was digested by mung bean nuclease (Fig. 1C, compare lanes 1 and 3). These results strongly suggest that the nucleic acid in the 0.4- to 2-kb fraction was composed of single-stranded DNA and small amounts of residual RNA, consistent with the interpretation that this fraction is enriched in nascent DNA (5, 44). This material was then used in a competitive PCR-based nascent-strand abundance assay to analyze initiation activity of the ectopic DNA fragment.

Targeted deletion analysis of the 5.8-kb ori-β DNA fragment using the strategy described in Fig. 1 revealed that several DNA sequence elements were required for full initiation activity of ectopic ori-β in DR12 hamster cells (summarized in Fig. 2A) (5). However, the deletion analysis did not rule out the possibility that the decreased activity of the ori-β mutants was due to altered spacing of potentially important flanking elements or to a need for a minimal fragment length for initiation activity (see reference 33 and references therein). To assess these possibilities, two of the deleted regions were replaced with stuffer DNA with different sequences but similar or identical length (Fig. 2B). These stuffer replacement mutants were transfected stably into ectopic sites in hamster DR12 cells that lack the entire DHFR locus (37). The initiation activity of the stuffer replacement mutants in uncloned cell pools was then measured using a PCR-based nascent-strand abundance assay and compared to the activity of the ectopic wild-type ori-β fragment (pMCD) and the previously described deletion mutants pMCDΔAT and pAKO (Fig. 2A; Table 3). Each construct was assayed in at least three independent transfection experiments, and the results of a typical experiment for each construct are listed in Table 3.

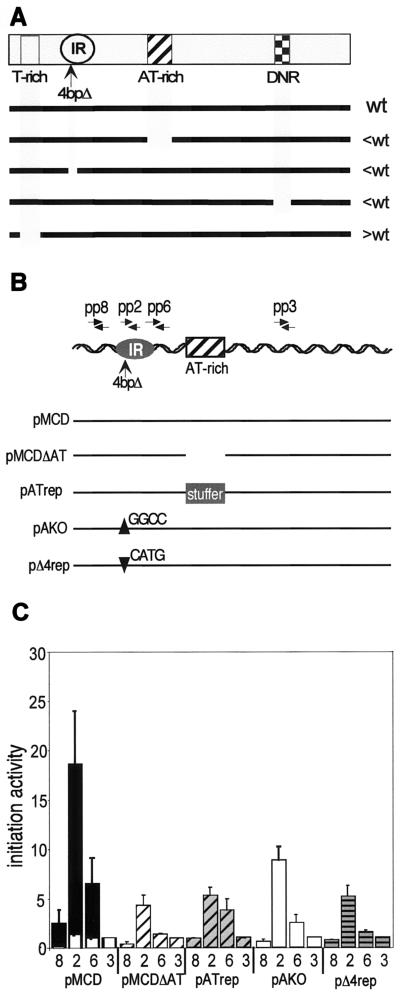

FIG. 2.

Analysis of replication initiation activity in exogenous ori-β DNA fragments containing deletion or substitution mutations. (A) Summary of initiation activity of ectopic ori-β DNA fragments containing targeted deletion mutations indicated by the heavy bars (see Table 1 for details) is expressed as greater than (>) or less than (<) that of the wild-type (wt) 5.8-kb DHFR ori-β fragment (5). The TR construct deleted a 263-bp asymmetric AT-rich element, the AKO construct deleted a 4-bp GGCC nucleotide sequence within the mapped IR, the ΔAT construct deleted an AT-rich element consisting of alternating As and Ts, and the ΔDNR construct deleted an extensive dinucleotide repeat element. (B) Diagram of the deletion and substitution mutations on the 5.8-kb DHFR ori-β IR fragment and the positions of the primers used in the PCR-based nascent-strand abundance assay (see Tables 1 and 2 for details). (C) The abundance of nascent DNA from pools of uncloned mutant-transfected DR12 cells from at least three independent transfection experiments with each construct was quantitatively measured. As a measure of initiation activity, the abundance of each target sequence in nascent genomic DNA was normalized to the abundance of primer pair 3 target sequences in the corresponding experiment, which was set equal to 1 (see Materials and Methods). The average initiation activity of three independent transfection experiments with each construct is shown. For comparison, the average initiation activity of the wild-type 5.8-kb DHFR ori-β fragment (black bars) and background activity for the assay system (white bars) are shown. Error bars, SEM.

TABLE 3.

Abundance of DHFR ori-β target DNA sequences in nascent DNAa

| DNA sourceb | Cell linec | Abundanced of DHFR ori-β target DNA (initiation activitye) with primer pair:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 2 | 6 | 3 | ||

| pMCDf | DR12 | 1.13 × 10−6 (3.7) | 9.10 × 10−6 (29.6) | 2.00 × 10−6 (6.5) | 3.08 × 10−7 (1) |

| pMCDΔATf | DR12 | 1.98 × 10−7 (0.7) | 1.18 × 10−6 (4.3) | 4.45 × 10−7 (1.6) | 2.73 × 10−7 (1) |

| pATrep | DR12 | 1.43 × 10−8 (0.9) | 7.57 × 10−8 (4.5) | 4.29 × 10−8 (2.6) | 1.65 × 10−8 (1) |

| pAKOf | DR12 | 1.54 × 10−7 (0.4) | 3.34 × 10−6 (7.4) | 6.56 × 10−7 (1.5) | 4.52 × 10−7 (1) |

| p4bpRep | DR12 | 1.67 × 10−7 (0.9) | 7.94 × 10−7 (4.1) | 2.14 × 10−7 (1.4) | 1.93 × 10−7 (1) |

| pBENDx | DR12 | 5.45 × 10−7 (0.9) | 1.04 × 10−6 (1.6) | 3.94 × 10−7 (0.6) | 6.32 × 10−7 (1) |

| pRIP DSx | DR12 | 4.95 × 10−8 (0.6) | 2.88 × 10−7 (3.5) | 1.57 × 10−7 (1.9) | 8.26 × 10−8 (1) |

| pLamRep | DR12 | 1.80 × 10−8 (0.4) | 1.14 × 10−5 (268.2) | 1.59 × 10−6 (37.4) | 4.25 × 10−8 (1) |

| pMCD | HCT | 2.43 × 10−8 (0.2) | 4.80 × 10−6 (39.3) | 1.36 × 10−6 (11.2) | 1.22 × 10−7 (1) |

| pMCD | HeLa | 1.36 × 10−8 (1.8) | 2.93 × 10−7 (39.1) | 1.42 × 10−7 (19.0) | 7.49 × 10−9 (1) |

| pMCDΔAT | HeLa | 3.23 × 10−8 (0.8) | 1.47 × 10−7 (3.8) | 2.17 × 10−7 (5.7) | 3.82 × 10−8 (1) |

| pATrep | HeLa | 3.81 × 10−8 (0.3) | 8.82 × 10−7 (5.8) | 2.13 × 10−7 (1.4) | 1.50 × 10−7 (1) |

| pLamRep | HeLa | 2.91 × 10−8 (0.5) | 8.86 × 10−7 (16.1) | 3.73 × 10−7 (6.8) | 5.47 × 10−8 (1) |

Values in the table are from a typical experiment out of at least three separate transfection experiments for each construct.

All DNA was isolated from pools of cells stably transfected with the mutant construct listed.

All DNA constructs were stably transfected into either DR12, HeLa, or HCT116 (HCT) cells.

Abundance was calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

Initiation activity, in parentheses, was calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

Previously published results (5).

The wild-type ori-β fragment directed robust replication initiation, as illustrated by the peak of initiation activity at primer pair 2 (Fig. 2C). As a control, the PCR-based nascent-strand abundance assay was also performed on total sheared genomic DNA, in which all target sequences should be equally represented. Although small variations were observed from one primer pair to another in the control, the consistently low values observed with all four primer sets (Fig. 2C) confirmed that the peak observed at primer pair 2 depended on using the nascent-strand-enriched fraction as the PCR template. The average initiation activity of ectopic pATrep in cell pools from three separate transfection experiments was markedly reduced compared to that of ectopic wild-type ori-β (Fig. 2C) and was similar to that of the deletion mutant pMCDΔAT (Fig. 2C, compare pMCDΔAT and pATrep). This result indicates that the stuffer DNA was unable to functionally substitute for the AT-rich element, suggesting that the sequence in the AT-element is specifically required for ectopic ori-β activity.

Deletion of 4 bp (pAKO) within the mapped IR also reproducibly decreased initiation activity at ectopic ori-β (Fig. 2A) (5). Although the decrease in initiation activity was modest, it is remarkable that such a minor nucleotide change affected ori-β activity at all. Deletion of 4 bp would be equivalent to about half of a helical turn and could disrupt local interactions between proteins bound to sites flanking the deletion or directly disrupt a protein binding site. To test these possibilities, the 4-bp GGCC nucleotide sequence was replaced with CATG (pΔ4rep [Fig. 2B]). This replacement was unable to restore initiation activity to the ectopic ori-β fragment (compare pAKO and pΔ4rep [Fig. 2C]), suggesting that the 4-bp sequence may be specifically involved in origin function rather than serving as a spacer. These results demonstrate that the AT-rich and the 4-bp element contribute in a sequence-specific manner to initiation activity at ectopic ori-β.

To identify other potential functional elements that may contribute to DHFR ori-β activity, mutational analysis of the ori-β IR was extended to other sequence elements studied previously (18). The ori-β IR contains a well-characterized region of intrinsically bent DNA located between the critical AT-rich element and the 4-bp element (Fig. 3A). The functional importance of the bent DNA for ori-β activity was examined by creating a mutation designed to remove the bend (pBENDx, Fig. 3B). The five phased A/T tracts that cause the bend were changed to alternating G and C tracts (Fig. 3B). Analysis of the predicted DNA structure of a 309-bp BglI-BglII DNA fragment indicated that replacing the five A/T tracts should significantly alter the local structure of the DNA, essentially “straightening out” the bent DNA region (Fig. 3C). In order to confirm experimentally that the sequence changes altered the architecture at the bend, wild-type and mutant constructs were digested with BglI and BglII to release a 309-bp fragment containing the bent DNA near the middle of the fragment. If the 309-bp DNA is bent, its electrophoretic mobility should be retarded relative to that of the unbent size marker DNA (64, 43). The GC substitutions should restore the mobility of the fragment to that expected for its length. As expected, the 309-bp DNA fragment containing the wild-type sequence (pMCD) had a retarded electrophoretic mobility, while the mutant 309-bp fragment (pBENDx) migrated at the position expected for its length, confirming that the mutant fragment lacked the bend (Fig. 3D). To determine whether the altered sequence affected ori-β initiation activity, the pBENDx mutant DNA was stably transfected into DR12 cells in three separate experiments and initiation activity in uncloned cell pools was measured by the PCR-based nascent-strand abundance assay. Little initiation activity was observed with the mutant pBENDx (Fig. 3E); its activity was not significantly different from that detected in the negative control (Fig. 3E). This result indicates that either the sequence-determined bend or the specific sequence that was mutated in this element is crucial for ectopic ori-β activity in hamster cells.

The intrinsically bent DNA element in ori-β was reported to undergo enhanced bending and looping in vitro in the presence of the zinc finger DNA-binding protein RIP60 (17, 21, 35). Two potential RIP60 binding sites of opposite polarity are located in ectopic ori-β (Fig. 4A, RIP US and RIP DS), one in the IR and the other directly adjacent to the region of bent DNA. Although it was not tested whether RIP60 binds to ori-β in vivo (17, 21, 35), the importance of the bent DNA element for ori-β activity raised the question of whether the enhanced bending facilitated by RIP60 in vitro might affect initiation activity of ectopic ori-β in vivo. To explore this possibility, we mutated the RIP60 binding site adjacent to the bent element (pRIP DSx) (Fig. 4B). Since the RIP60 binding site mutation did not alter the nucleotides in the adjacent A/T tract of the bent DNA element, the 309-bp BglI-BglII fragment of pRIP DSx should retain the distinctive bend predicted by DNA structure analysis (Fig. 4C). To test this prediction experimentally, the electrophoretic mobility of the 309-bp BglI-BglII DNA fragment of pRIP DSx was examined. The mobility of the mutant fragment was slightly lower than that of the wild-type fragment, indicating that the mutant retained a region of DNA bending (Fig. 4D). The lower mobility of the mutant fragment may indicate that its three-dimensional conformation differs slightly from that in pMCD. The initiation activity of the ectopic pRIP DSx mutant in pools of stably transfected cells was tested using the PCR-based nascent-strand abundance assay. The activity of ectopic pRIP DSx was markedly decreased relative to that of pMCD (Fig. 4E), implying that the sequence of the RIP60 consensus binding site is important for full initiation activity at ectopic ori-β in hamster cells.

Taken together, these results indicate that at least four defined elements contribute in a sequence-specific manner to ectopic ori-β activity in hamster cells, in that these elements cannot be functionally replaced by unrelated DNA sequences.

A 5.8-kb DNA fragment containing the hamster DHFR ori-β IR is sufficient to direct initiation at ectopic sites in human chromosomes.

Several mammalian origins have been reported to be active in cells or extracts of other vertebrate species (4, 25, 47, 65), yet no consensus DNA sequences have been identified that are conserved from one origin to another (4, 9, 31, 61). As a possible resolution for this conundrum, we reasoned that if replicators are indeed comprised of specific elements that contribute to initiation activity, as suggested by the results presented above and elsewhere (49), some of these elements could still be functionally conserved among different replicators in vertebrates.

To test this notion, we wished to determine whether the elements that contribute to hamster DHFR ori-β activity in ectopic chromosomal locations in the hamster cell would also be important for ori-β activity in other mammalian cell lines. As a first step, we asked whether the wild-type ori-β IR was active at ectopic chromosomal sites in human cells. The 5.8-kb DNA fragment containing ori-β (pMCD) was stably transfected into two human cell lines, HeLa and HCT116. The PCR-based nascent-strand abundance assay was used to measure initiation activity of ectopic ori-β in nascent genomic DNA from pools of uncloned cells. A peak of initiation activity was easily detectable in both cell types at the same position observed with the ectopic ori-β in hamster cells (Fig. 5A). Ectopic ori-β was equally active in HeLa and HCT116 cells, and the initiation activity in both human lines was about twice that in DR12 cells (Fig. 5A).

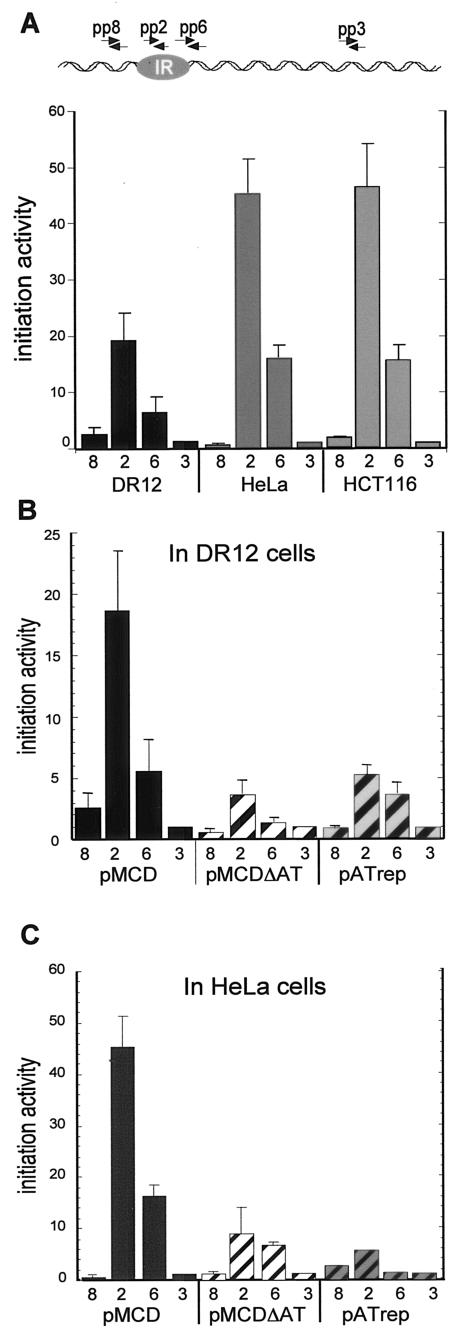

FIG. 5.

Initiation of DNA replication in wild-type and mutant ori-β in ectopic chromosomal locations in hamster and human cells. (A) The abundance of nascent DNA from pools of uncloned pMCD-transfected DR12 (black bars), HeLa (dark gray bars), and HCT116 (light gray bars) cells was quantitatively measured in three independent transfection experiments with each cell line. The positions of PCR primer pairs in the 5.8-kb ori-β fragment are indicated at the top (Table 2). As a measure of initiation activity, the abundance of each target sequence in nascent genomic DNA was normalized to the abundance of primer pair 3 target sequences in the corresponding experiment, which was set equal to 1 (Materials and Methods). The average of the three independent transfection experiments is shown. Error bars, SEM. (B and C) Average initiation activity measured in three separate transfections with pMCDΔAT or pATrep into either DR12 (B) or HeLa cells (C) is shown. Error bars, SEM.

Although wild-type ori-β appeared to fire in human cells, it remained possible that the sequence elements that contribute to its initiation activity may differ in the human and hamster cell backgrounds. To assess whether the AT element was required for ectopic ori-β activity in human cells, the AT deletion (pMCDΔAT) and substitution (pATrep) mutants were stably transfected into HeLa cells and activity of ectopic ori-β was assayed in a nascent DNA fraction from pools of uncloned cells. Initiation activities of both mutants in human cells were decreased (Fig. 5B and C). The relative decrease in activity displayed by the two mutants in human cells was proportional to that observed in hamster cells (Fig. 5B and C). We conclude that the AT-rich element is required for full initiation activity of ectopic ori-β in both human and hamster cells.

A 6.5-kb DNA fragment containing the human lamin B2 IR is sufficient to direct initiation at ectopic chromosomal sites in a hamster cell line.

The finding that a hamster replicator directs initiation at ectopic sites in human cells and that at least one element critical for its activity in hamster cells is also needed for full activity in the human cell milieu led us to question whether a human origin could serve as a replicator in a hamster cell background. The human lamin B2 IR has been mapped by quantitative PCR with a peak of initiation activity occurring near the 3′ end of the lamin B2 coding sequence (30) (Fig. 6A). The start sites of leading-strand synthesis were fine-mapped to a single nucleotide on each strand and were separated by only four nucleotides (2). In addition, the human lamin B2 start site is associated with prereplication complexes that presumably direct initiation (1).

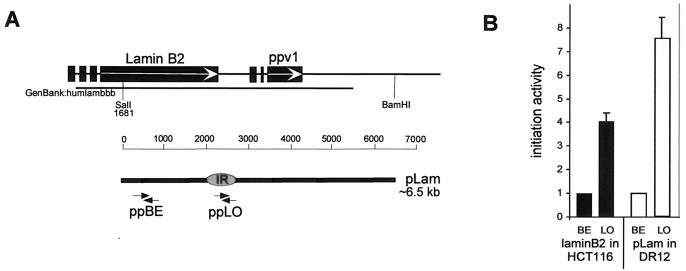

FIG. 6.

A human lamin B2 DNA fragment functions as a replicator in ectopic locations in hamster chromosomes. (A) Features of the endogenous human lamin B2 IR. The start site of DNA replication (shaded oval, IR) is located between the lamin B2 gene and the ppv1 gene, in the 3′ noncoding end of the lamin B2 gene (30). A 6.5-kb DNA fragment (pLam) of the lamin B2 origin region, extending from the SalI (nucleotide position 1681, GenBank accession number M94363, humlambbb) to the BamHI recognition site is indicated (heavy black bar). Arrows denote the positions of the primers used in the PCR-based nascent-strand abundance assay (Table 2). (B) The abundance of nascent DNA from HCT116 cells (black bars) or pools of uncloned pLam-transfected DR12 cells (dotted bars) was quantitatively measured in three independent transfection experiments. As a measure of initiation activity, the abundance of each target sequence in nascent genomic DNA was normalized to the abundance of outlying primer pair BE target sequences in the corresponding experiment, which was set equal to one (see Materials and Methods). The average initiation activity of three independent transfection experiments is shown. Error bars, SEM.

To determine whether a human lamin B2 fragment could serve as a replicator at ectopic sites in hamster cells, we stably transfected a 6.5-kb DNA fragment containing the lamin B2 start site (pLam) into DR12 cells (Fig. 6A). To validate our assay, initiation activity was first measured at the endogenous locus in human cells by using the competitive PCR-based nascent-strand abundance assay. Two primer sets (Table 2)—one corresponding to the previously mapped lamin B2 IR, primer pair LO, and one outlying primer, primer pair BE—were used to facilitate comparison of our results with previous work (30). Lamin B2 initiation activity measured at primer pair LO in the endogenous locus in HCT116 cells was about fourfold higher than that at the outlying primer pair BE (Table 4; Fig. 6B). This ratio is identical to that reported previously for the endogenous locus in human cells, after recalculation of the published data to take amplicon length into account (30). Interestingly, initiation activity at primer pair LO in pLam-transfected hamster DR12 cells was about sevenfold higher than that at the outlying primer pair BE, indicating that the ectopic human lamin B2 IR was selected and activated quite well in the hamster cell background (Table 4; Fig. 6B). Similar results were obtained using primer pair B48 instead of primer pair LO to analyze ectopic pLam in nascent DNA from hamster cells (not shown). These results demonstrate that the 6.5-kb human lamin B2 DNA fragment contains a replicator that is active at ectopic chromosomal sites in hamster cells.

TABLE 4.

Abundance of lamin B2 target DNA sequences in nascent DNAa

| DNA sourceb | Cell linec | Abundanced of lamin B2 target DNA (initiation activitye) with primer pair:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| LO | BE | ||

| Lamin B2 | HCT | 6.8 × 10−8 (4.1) | 1.7 × 10−8 (1) |

| pLam | DR12 | 1.3 × 10−7 (7.2) | 1.8 × 10−8 (1) |

Values in the table are from a typical experiment out of three separate transfection experiments with each construct.

DNA was isolated from untransfected HCT116 cells or from pools of cells stably transfected with the pLam construct.

Plasmid pLam containing the lamin B2 DNA was stably transfected into DR12 cells and compared to endogenous lamin B2 in HCT116 (HCT) cells.

Abundance was calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

Initiation activity, in parentheses, was calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

A DNA fragment from the human lamin B2 replicator substitutes for the AT-rich element in hamster ori-β.

The findings in Fig. 5 and 6 provide an opportunity to address the question of whether the AT-rich element in ori-β represents a functional element shared by the lamin B2 replicator. If it does, the AT element should be interchangeable with a functionally analogous element from the lamin B2 origin. To test this prediction, we replaced the large AT-rich element of hamster ori-β (344 bp) by a large AT-rich DNA fragment (224 bp) from the human lamin B2 IR (Fig. 7A, pLamRep). The 224-bp fragment contains the lamin B2 start sites for leading-strand synthesis on both template strands, is protected from DNase I in a cell cycle-dependent manner, and is associated with prereplication complexes in human cells (1, 2, 3, 26).

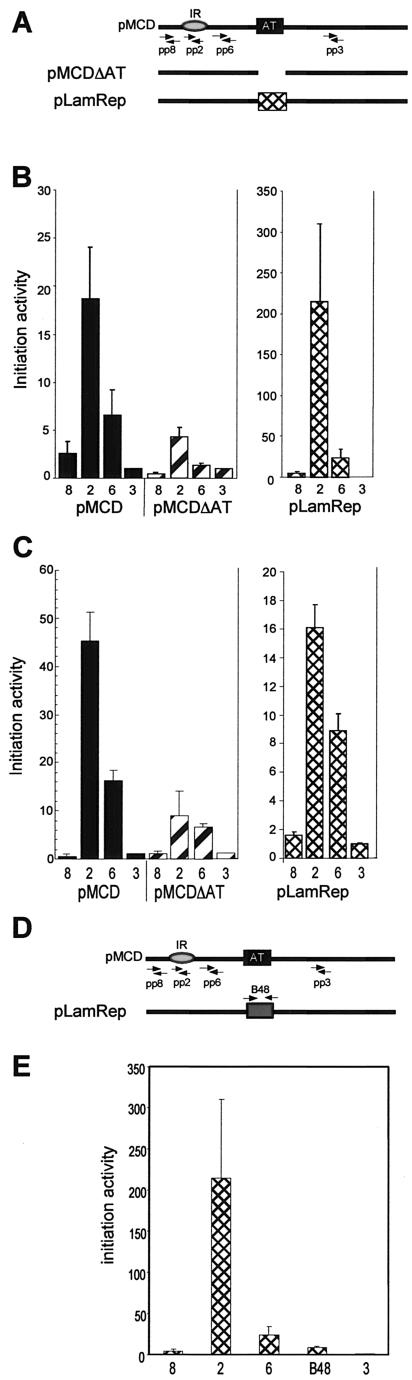

FIG.7.

A DNA sequence element from the human lamin B2 origin substitutes for the DHFR ori-β AT-rich element. (A) Location of the deletion and substitution mutations on the 5.8-kb DHFR ori-β replicator. Arrows denote the positions of the primers used in the PCR-based nascent-strand abundance assay (Table 2). (B and C) The abundance of nascent DNA from pools of pMCD, pMCDΔAT, or pLamRep-transfected DR12 (B) or HeLa cells (C) from three independent transfection experiments with each construct in each line was quantitatively measured, and the average initiation activity from three separate experiments is shown. Error bars, SEM. (D) Location of the B48 primer set (Table 2) used to amplify the lamin B2 replacement fragment in the PCR-based nascent-strand abundance assay. (E) The abundance of nascent DNA from pools of pLamRep-transfected DR12 cells from three independent transfection experiments was quantitatively measured, and the average initiation activity from the three experiments is shown. Error bars, SEM.

The replacement mutant construct pLamRep was stably transfected into DR12 cells, and initiation activity in cell pools was determined in the PCR-based nascent-strand abundance assay. As indicated in Fig. 7B, the AT-rich element from the lamin B2 IR substituted for the ori-β AT-rich element. In fact, initiation activity at the ori-β start site was about 10-fold greater in the pLamRep mutant than in the wild-type ectopic ori-β in hamster cells (Fig. 7B, compare ordinates). The initiation activities of ectopic pLamRep and pMCD were also compared in the human cell background (Fig. 7C). Interestingly, the initiation activity of pLamRep was only about half that of ectopic wild-type ori-β (Fig. 7C), indicating that the lamin B2 element substituted only partially for the AT-rich element in ori-β in the human cell background. Moreover, the peak of initiation activity in pLamRep was somewhat broader than that in pMCD, as shown by the enhanced activity at primer pair 6 (Fig. 7C).

Since the AT-rich lamin B2 fragment used in the pLamRep mutant of ori-β contains the start site mapped at the endogenous lamin B2 locus (2, 30), we wondered whether the lamin B2 start site might be activated in the context of the pLamRep mutant of ori-β. To assess this possibility, nascent DNA from pools of stably transfected DR12 cells was tested in the competitive PCR-based nascent-strand abundance assay using the B48 primer set that was originally used to map the initiation site in the lamin B2 origin (30) (Table 2; Fig. 7D). The initiation activity detected in the lamin B2 sequence of the pLamRep mutant of ori-β was close to background level (Fig. 6E), demonstrating that the lamin B2 IR was not measurably activated in the context of ori-β in hamster cells. Due to the endogenous lamin B2 locus, initiation activity at the lamin B2 element of ectopic pLamRep could not be unambiguously determined in the human cell background.

DISCUSSION

Mammalian chromosomes contain replicator elements that direct initiation locally.

The results presented here and previously (5) demonstrate that a 5.8-kb DNA fragment containing the hamster DHFR ori-β IR serves as a replicator in ectopic chromosomal locations in both hamster and human cells. Using the same strategy, we show here that the human lamin B2 origin in a 6.5-kb fragment is recognized and activated at ectopic chromosomal sites in hamster cells, indicating that this fragment also serves as a replicator. While this manuscript was under review, a 1.2-kb lamin B2 DNA fragment was shown to serve as a replicator at random ectopic sites in human cells (G. Biamonti, personal communication). A related strategy has been used to demonstrate that a 2.4-kb fragment from the human c-myc locus serves as a replicator at a defined ectopic chromosomal site in HeLa cells (reference 49 and references therein) and that an 8-kb fragment of the human β-globin locus serves as a replicator at two ectopic chromosomal sites in monkey cells (4).

It remains unknown what the minimal sequence might be that constitutes replicator activity in mammalian chromosomes, but all four of the mammalian replicators identified so far appear to be larger than most replicators in budding or fission yeast. Like those of yeast, they reside in intergenic regions and contain stretches of AT-rich sequence (53, 57, 66). Of course, all of them also contain the previously mapped IR that led investigators to test them for replicator activity, and one of them, the lamin B2 replicator, is bound to pre-RC proteins in a cell cycle-dependent manner in vivo (1). One suspects that the other mammalian replicators are likely to bind pre-RC proteins as well, and it will be interesting to see whether ORC binding is essential for replicator activity at these IRs.

Multiple sequence elements contribute to replicator activity of ori-β.

The data presented in this report indicate that four distinct elements are required in a sequence-specific fashion for full ori-β activity in hamster cells. These elements include an AT-rich element, a 4-bp sequence located within the mapped IR, a region of AT-rich bent DNA located between these two elements, and an AT-rich RIP60 protein binding site adjacent to the bent region. The dinucleotide repeat element in the 5.8-kb ori-β fragment also appears to contain DNA sequences that are specifically required for replicator activity (5; S. Gray, A. Altman, and E. Fanning, unpublished data). These five elements are dispersed throughout most of the 5.8-kb fragment. In contrast, an asymmetric AT-rich sequence (TR) located near the 5′ end of the 5.8-kb fragment was previously shown to be dispensable for ori-β activity (5). All five essential elements have been assayed by nucleotide substitution, as well as by deletion mutagenesis, in the context of multiple undefined chromosomal integration sites found in pools of uncloned transfected cells. We speculate that possible position effects caused by ori-β integration into certain chromosomal sites would be obscured in this approach. Whether all five elements would also be essential when the mutant ori-β replicators are analyzed in a single defined ectopic chromosomal site is an open question. Nevertheless, mutational analysis of the ectopic β-globin (4) and c-myc replicators (49) placed at unique chromosomal integration sites by site-specific recombination has also revealed several sequence elements that are required for initiation activity. Taken together, these results suggest that mammalian chromosomal replicators may be quite complex and their activity may depend on multiple elements composed of specific DNA sequences that are distributed over a region of several kilobases.

The biochemical mechanisms by which these elements affect replicator activity remain unknown. They may bind ORC, transcription factors, and perhaps other as yet unidentified proteins or affect local chromatin organization or other aspects of chromosome architecture. It will be of great interest to compare the sequence modules needed for activity in the various mammalian replicators and their biochemical functions. Perhaps, like transcriptional control sequences, the collection of modules controlling replication in mammalian chromosomes is larger and more complex than those used in budding yeast (46).

Possible functional conservation of an AT-rich element in two mammalian chromosomal replicators.

AT-rich DNA sequences are frequently found in origins of replication and may be selectively bound by ORC in eukaryotes (references 6 and 61 and references therein). The AT-rich region located downstream from the ori-β start site appears to be crucial for replication initiation (Fig. 2A and C). Deletion of a 344-bp fragment containing a stretch of alternating AT residues reduced activity to near background levels (Fig. 2C [pMCDΔAT]) (5). The fact that an unrelated stuffer DNA fragment was unable to substitute for the AT-rich element argues that the AT-rich element is a specific sequence element required for origin activity (Fig. 2C). Given that the fragment deleted in the pMCDΔAT mutant was 65% AT, whereas the 297-bp nonorigin stuffer DNA was only 40% AT, it was possible that AT richness or a minimal length rather than a specific sequence was required for activity. This seems unlikely, however, since an even shorter (224-bp) element of only 58% AT from the human lamin B2 origin substituted functionally for the activity of the ori-β AT-element in hamster cells (Fig. 7B), as well as partially in human cells (Fig. 7C). Also consistent with a sequence-specific requirement, an AT-rich element in the human c-myc origin could not be functionally replaced even by a nonorigin fragment of exactly the same length and AT richness (49). These results indicate that replicators may be composed of functionally different classes of AT-rich sequences, some of them able to functionally substitute for each other while others cannot, raising the question of what these functions may be. Biochemical studies to examine pre-RC proteins associated with ori-β, the mutants lacking the AT element, and the pLamRep mutant may reveal whether the AT element and the 224-bp lamin B2 element share common biochemical functions.

In summary, the results presented here show that the ectopic DHFR ori-β replicator is active in both hamster and human cells and that a human lamin B2 fragment is active as a replicator at ectopic sites in hamster chromosomes. Mutational analysis of the ori-β replicator strongly suggests that at least four defined sequence modules, including an architectural element, are required for full activity of ectopic ori-β, and that one of these elements can be fully or partially replaced by an element from the lamin B2 origin. Studies to determine whether any of these sequences interact with initiator proteins in vivo may elucidate the roles of these elements in the events leading up to the initiation of DNA synthesis.

Acknowledgments

The financial support of the NIH (grant GM 52948 and training grant CA 09385), the Army Breast Cancer Program (BC980907), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Professors Program (52003905), and Vanderbilt University is gratefully acknowledged.

We thank M. Giacca and N. Heintz for plasmids; S. Gray, M. Giacca, and A. Patten for stimulating discussion; and S. Gray, A. Patten, G. Biamonti, and M. Debatisse for sharing unpublished data with us.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdurashidova, G., B. Danailov, A. Ochem, G. Triolo, V. Djeliova, S. Radulescu, A. Vindigni, S. Riva, and A. Falaschi. 2003. Localization of proteins bound to a replication origin of human DNA along the cell cycle. EMBO J. 22:4294-4303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdurashidova, G., M. Deganuto, R. Klima, S. Riva, G. Biamonti, M. Giacca, and A. Falaschi. 2000. Start sites of bidirectional DNA synthesis at the human lamin B2 origin. Science 287:2023-2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdurashidova, G., S. Riva, G. Biamonti, M. Giacca, and A. Falaschi. 1998. Cell cycle modulation of protein-DNA interactions at a human replication origin. EMBO J. 17:2961-2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aladjem, M. I., L. W. Rodewald, J. L. Kolman, and G. M. Wahl. 1998. Genetic dissection of a mammalian replicator in the human β-globin locus. Science 281:1005-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altman, A. L., and E. Fanning. 2001. The Chinese hamster dihydrofolate reductase replication origin beta is active at multiple ectopic chromosomal locations and requires specific DNA sequence elements for activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:1098-1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anglana, M., F. Apiou, A. Bensimon, and M. Debatisse. 2003. Dynamics of DNA replication in mammalian somatic cells: nucleotide pool modulates origin choice and interorigin spacing. Cell 114:385-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Austin, R. J., T. L. Orr-Weaver, and S. P. Bell. 1999. Drosophila ORC specifically binds to ACE3, an origin of DNA replication control element. Genes Dev. 13:2639-2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beall, E. L., J. R. Manak, S. Zhou, M. Bell, J. L. Lipsick, and M. R. Botchan. 2002. Role for a Drosophila Myb-containing protein complex in site-specific DNA replication. Nature 420:833-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bell, S. P. 2002. The origin recognition complex: from simple origins to complex functions. Genes Dev. 16:659-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell, S. P., and A. Dutta. 2002. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71:333-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bielinsky, A. K., H. Blitzblau, E. L. Beall, M. Ezrokhi, H. S. Smith, M. R. Botchan, and S. A. Gerbi. 2001. Origin recognition complex binding to a metazoan replication origin. Curr. Biol. 11:1427-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bielinsky, A.-K., and S. A. Gerbi. 1998. Discrete start sites for DNA synthesis in the yeast ARS1 origin. Science 279:95-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bielinsky, A.-K., and S. A. Gerbi. 1999. Chromosomal ARS1 has a single leading strand start site. Mol. Cell 3:477-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bogan, J. A., D. A. Natale, and M. L. DePamphilis. 2000. Initiation of eukaryotic DNA replication: conservative or liberal? J. Cell Physiol. 184:139-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brattain, M. G., D. E. Brattain, A. M. Sarrif, L. J. McRae, W. D. Fine, and J. G. Hawkins. 1982. Enhancement of growth of human colon tumor cell lines by feeder layers of murine fibroblasts. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 69:767-771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brattain, M. G., W. D. Fine, F. M., Khaled, J. Thompson, and D. E. Brattain. 1981. Heterogeneity of malignant cells from a human colonic carcinoma. Cancer Res. 41:1751-1756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caddle, M. S., L. Dailey, and N. H. Heintz. 1990. RIP60, a mammalian origin-binding protein, enhances DNA bending near the dihydrofolate reductase origin of replication. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:6236-6243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caddle, M. S., R. H. Lussier, and N. H. Heintz. 1990. Intramolecular DNA triplexes, bent DNA and DNA unwinding elements in the initiation region of an amplified dihydrofolate reductase replicon. J. Mol. Biol. 211:19-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chuang, R. Y., and T. J. Kelly. 1999. The fission yeast homologue of Orc4p binds to replication origin DNA via multiple AT-hooks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:2656-2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clyne, R. K., and T. J. Kelly. 1995. Genetic analysis of an ARS element from the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. EMBO J. 14:6348-6357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dailey, L., M. S. Caddle, N. Heintz, and N. H. Heintz. 1990. Purification of RIP60 and RIP100, mammalian proteins with origin-specific DNA-binding and ATP-dependent helicase activities. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:6225-6235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhar, V., D. Mager, A. Iqbal, and C. L. Schildkraut. 1988. The coordinate replication of the human beta-globin gene domain reflects its transcriptional activity and nuclease hypersensitivity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:4958-4965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dijkwel, P. A., and J. L. Hamlin. 1995. The Chinese hamster dihydrofolate reductase origin consists of multiple potential nascent-strand start sites. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:3023-3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dijkwel, P. A., S. Wang, and J. L. Hamlin. 2002. Initiation sites are distributed at frequent intervals in the Chinese hamster dihydrofolate reductase origin of replication but are used with very different efficiencies. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:3053-3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dimitrova, D. S., and D. M. Gilbert. 1998. Regulation of mammalian replication origin usage in Xenopus egg extract. J. Cell Sci. 111:2989-2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dimitrova, D. S., M. Giacca, F. Demarchi, G. Biamonti, S. Riva, and A. Falaschi. 1996. In vivo protein-DNA interactions at a human DNA replication origin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:1498-1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diviacco, S., P. Norio, L. Zentilin, S. Menzo, M. Clementi, G. Biamonti, S. Riva, A. Falaschi, and M. Giacca. 1992. A novel procedure for quantitative polymerase chain reaction by coamplification of competitive templates. Gene 122:313-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Epner, E., W. C. Forrester, and M. Groudine. 1988. Asynchronous DNA replication within the human beta-globin gene locus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:8081-8085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gey, G. O., W. D. Coffman, and M. T. Kubicek. 1952. Tissue culture studies of the proliferative capacity of cervical carcinoma and normal epithelium. Cancer Res. 12:264-265. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giacca, M., L. Zentilin, P. Norio, S. Diviacco, D. Dimitrova, G. Contreas, G. Biamonti, G. Perini, F. Weighardt, S. Riva, and A. Falaschi. 1994. Fine mapping of a replication origin of human DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:7119-7123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilbert, D. M. 2001. Making sense of eukaryotic origins of DNA replication. Science 294:96-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilbert, D. M. 2002. Replication timing and transcriptional control: beyond cause and effect. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14:377-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heintzel, S. S., P. J. Krysan, C. T. Tran, and M. P. Calos. 1991. Autonomous DNA replication in human cells is affected by the size and the source of the DNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:2263-2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hochheimer, A., and R. Tjian. 2003. Diversified transcription initiation complexes expand promoter selectivity and tissue-specific gene expression. Genes Dev. 17:1309-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Houchens, C. R., W. Montigny, L. Zeltser, L. Dailey, J. M. Gilbert, and N. H. Heintz. 2000. The DHFR ori beta-binding protein RIP60 contains 15 zinc-fingers: DNA binding and looping by the central three fingers and an associated proline-rich region. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:70-581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacob, F., S. Brenner, and F. Cuzin. 1963. On the regulation of DNA replication in bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 28:329-348. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin, Y., T. Yie, and A. Carothers. 1995. Non-random deletions at the dihydrofolate reductase locus of Chinese hamster ovary cells induced by α-particle stimulating radon. Carcinogenesis 16:1981-1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keller, C., E. M. Ladenburger, M. Kremer, and R. Knippers. 2002. The origin recognition complex marks a replication origin in the human TOP1 gene promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 277:31430-31440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim, S.-M., and J. A. Huberman. 1998. Multiple orientation-dependent, synergistically interacting, similar domains in the ribosomal DNA replication origin of the fission yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:7294-7303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobayashi, T., T. Rein, and M. L. DePamphilis. 1998. Identification of primary initiation sites for DNA replication in the hamster dihydrofolate reductase gene initiation zone. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:3266-3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kong, D., and M. L. DePamphilis. 2001. Site-specific DNA binding of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe origin recognition complex is determined by the Orc4 subunit. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:8095-8103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kong, D., and M. L. DePamphilis. 2002. Site-specific ORC binding, pre-replication complex assembly and DNA synthesis at Schizosaccharomyces pombe replication origins. EMBO J. 21:5567-5576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koo, H. S., H. M. Wu, and D. M. Crothers. 1986. DNA bending at adenine/thymine tracts. Nature 320:501-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar, S., M. Giacca, P. Norio, G. Biamonti, S. Riva, and A. Falaschi. 1996. Utilization of the same DNA replication origin by human cells of different derivation. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:3289-3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ladenburger, E. M., C. Keller, and R. Knippers. 2002. Identification of a binding region for human origin recognition complex proteins 1 and 2 that coincides with an origin of DNA replication. Mol. Cell Biol. 22:1036-1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levine, M., and R. Tjian. 2003. Transcription regulation and animal diversity. Nature 424:147-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li, C. J., J. A. Bogan, D. A. Natale, and M. L. DePamphilis. 2000. Selective activation of pre-replication complexes in vitro at specific sites in mammalian nuclei. J. Cell Sci. 113:887-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lipford, J. R., and S. P. Bell. 2001. Nucleosomes positioned by ORC facilitate the initiation of DNA replication. Mol. Cell 7:21-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu, G., M. Malott, and M. Leffak. 2003. Multiple functional elements comprise a mammalian chromosomal replicator. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:1832-1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malott, M., and M. Leffak. 1999. Activity of the c-myc replicator in an ectopic chromosomal location. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:5685-5695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mechali, M. 2001. DNA replication origins: from sequence specificity to epigenetics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2:640-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mesner, L. D., X. Li, P. A. Dijkwel, and J. L. Hamlin. 2003. The dihydrofolate reductase origin of replication does not contain any nonredundant genetic elements required for origin activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:804-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Newlon, C. S., and J. F. Theis. 2002. DNA replication joins the revolution: whole-genome views of DNA replication in budding yeast. Bioessays 24:300-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Okuno, Y., H. Satoh, M. Sekiguchi, and H. Masukata. 1999. Clustered adenine/thymine stretches are essential for function of a fission yeast replication origin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:6699-6707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pelizon, C., S. Diviacco, A. Falaschi, and M. Giacca. 1996. High-resolution mapping of the origin of DNA replication in the hamster dihydrofolate reductase gene domain by competitive PCR. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:5358-5364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Phi-van, L., C. Sellke, A. von Bodenhousen, and W. H. Stratling. 1998. An initiation zone of chromosomal DNA replication at the chicken lysozyme gene locus. J. Biol. Chem. 273:18300-18307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Raghuraman, M. K., E. A. Winzeler, D. Collingwood, S. Hunt, L. Wodicka, A. Conway, D. J. Lockhart, R. W. Davis, B. J. Brewer, and W. L. Fangman. 2001. Replication dynamics of the yeast genome. Science 294:115-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simpson, R. T. 1990. Nucleosome positioning can affect the function of a cis-acting DNA element in vivo. Nature 343:387-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takahashi, T., E. Ohara, H. Nishitani, and H. Masukata. 2003. Multiple ORC binding sites are required for efficient MCM loading and origin firing in fission yeast. EMBO J. 22:964-974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takahashi, T., and H. Masukata. 2001. Interaction of fission yeast ORC with essential adenine/thymine stretches in replication origins. Genes Cells 6:837-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vashee, S., C. Cvetic, W. Lu, P. Simancek, T. J. Kelly, and J. C. Walter. 2003. Sequence-independent DNA binding and replication initiation by the human origin recognition complex. Genes Dev. 17:1894-1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Waltz, S. E., A. A. Triveda, and M. Leffak. 1996. DNA replication initiates non-randomly at multiple sites near the c-myc gene in HeLa cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:1887-1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilmes, G. M., and S. P. Bell. 2002. The B2 element of Saccharomyces cerevisiae ARS1 origin of replication requires specific sequences to facilitate pre-RC formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:101-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu, H. M., and D. M. Crothers. 1984. The locus of sequence-directed and protein-induced DNA bending. Nature 308:509-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu, J. R., G. Yu, and D. M. Gilbert. 1997. Origin-specific initiation of mammalian nuclear DNA replication in a Xenopus cell-free system. Methods 13:313-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wyrick, J. J., J. G. Aparicio, T. Chen, J. D. Barnett, E. G. Jennings, R. A. Young, S. P. Bell, and O. M. Aparicio. 2001. Genome-wide distribution of ORC and MCM proteins in S. cerevisiae: high-resolution mapping of replication origins. Science 294:2357-2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zar, J. H. 1996. Biostatistical analysis, 4th ed. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, N.J.