Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Nursing home residents’ ability to independently function is associated with their quality of life. The impact of amputations on functional status in this population remains unclear. This analysis evaluated the effect of amputations—Transmetatarsal (TMA), Below-knee (BK), and Above-knee (AK)—on residents’ ability to perform self-care activities.

METHODS:

Medicare inpatient claims were linked with nursing home assessment data to identify admissions for amputation. The MDS ADL-Long form score (0-28; higher indicating greater impairment), based on seven activities of daily living, was calculated before and after amputation. Hierarchical modeling determined the effect of the surgery on residents’ post-amputation function. Controlling for comorbidity, cognition, and pre-hospital function allowed for evaluation of activities of daily living (ADL) trajectories over time.

RESULTS:

4965 residents underwent amputation: 490 TMA, 1596 BK and 2879 AK. Mean age was 81 and 54% of the patients were women. Most were White (67%) or African-American (26.5%). Comorbidities prior to amputation included diabetes (DM, 70.7%), coronary heart disease (57.1%), chronic kidney disease (53.6%), and/or congestive heart failure (CHF, 52.1%). Mortality within 30 days of hospital discharge was 9.0% and hospital readmission was 27.7%. Stroke, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), and poor baseline cognitive function were associated with the poorest functional outcome after amputation. Compared with residents who received TMA, those who had BK or AK recovered more slowly and failed to return to baseline function by six months. BK was found to have a superior functional trajectory compared with AK.

CONCLUSIONS:

Elderly nursing home residents undergoing BK or AK amputation failed to return to their functional baseline within six month. Among frail elderly nursing home residents, higher amputation level, stroke, ESRD, poor baseline cognitive scores, and female gender were associated with inferior functional status after amputation. These factors should be strongly assessed to maintain activities of daily living and quality of life in the nursing home population.

Introduction

Although amputation is a common procedure performed in elderly patients, few data exist regarding the effects of amputation on their functional status and the impact of these procedures on Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) in nursing home residents. ADLs — a person’s basic personal care activities such as eating, dressing and mobility—are associated with nursing home residents’ quality of life. ADL impairments are associated with hospital admission,(1) death,(2) and poorer physical health.(3) Data describing ADLs are readily available on the Minimum Data Set (MDS), the assessment portion of the Resident Assessment Instrument, a federally-mandated process for all residents in nursing homes that are certified by Medicaid or Medicare.(4) In addition to ADLs, the MDS includes information on cognition, communication, behavior, diagnoses, nutrition, activity, and medication and other treatments. For analysis, seven activities’ scores were summed to form a scale from 0 to 28, with 0 indicating complete independence in all seven activities and 28 indicating complete dependence

MDS assessments are used to develop detailed care plans for nursing home residents. Self-performance of ADL activities on the MDS have shown good reliability – Spearman-Brown correlations for six ADLs was 0.75 or higher,(5) and dual assessments by trained nurses yielded high Spearman-Brown intraclass correlations (0.92).(6) In addition to care planning, MDS data can be used to calculate ADL summary scales that represent a resident's ADL status.(5) To determine the functional outcomes of nursing home residents after amputation, we evaluated their ADL function before and after amputations that included above-knee (AK), below-knee (BK), and Transmetatarsal (TMA) procedures. The association of comorbidities and cognitive status on the functional trajectories after intervention were also assessed.

Methods

We examined physical function of long-term nursing home residents before and after a hospitalization during which an amputation was performed. We used hierarchical modeling to determine the association between amputation level and post-hospital trajectories of ADL function. The study was approved by the Health Sciences Institutional Review Board at the University of Missouri.

Data and measures

We linked Medicare inpatient claims for 2006-2007 with nursing home MDS assessments to form a cohort of long-stay residents who were hospitalized for an amputation. MDS assessments are used to develop comprehensive care plans, and are federally mandated for all residents of nursing homes that are certified by Medicare or Medicaid.(4) Typically, MDS assessments are performed quarterly, with more detailed assessments occurring at least annually. MDS assessments may also occur when a resident’s status changes substantially or when they receive Medicare-paid skilled nursing care following hospitalization. We included each resident’s last pre-hospital MDS assessment and all post-hospital MDS assessments during the six months after hospital discharge, up to the point of readmission or death.

We used the MDS ADL-Long form score(5) to represent ADL function. The score is a sum of seven variables representing self-care activities on the MDS (bed mobility, self-transfer, locomotion on unit, dressing, eating, toileting and personal hygiene). These activities are scored from 0 to 4, where 0 indicates independence in performing the activity and 4 indicates total dependence on others (see Appendix for a detailed explanation). Activities that did not occur at all during the prior week are given a score of 8; 8s are recoded to 4s to calculate the scale. The sum varies from 0 to 28, with 0 indicating complete independence in all seven activities and 28 indicating complete dependence. A 2-point change in the total score indicates new or substantially increased requirement for physical assistance for one component activity, or the addition of new supervision, cueing, or physical assistance for two ADL items. A 1-point change indicates new supervision or cueing, or new or increased physical assistance for one ADL. Carpenter(7) reported that a 1-point change on the scale represents clinically meaningful change. Using a similar scale based on summing scores for five ADL items, McConnell(8) also considered a 1-point change on a 0-20 point scale as clinically important. We also calculated the Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS) from each resident’s first included MDS assessment.(9) The CPS is a 0-6 scale, with 0 representing intact cognition and 6 representing severe cognitive impairment.

Appendix. Description of scoring for ADL self-performance items

| Score | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | Independent – no help or oversight – OR – help/oversight provided only 1 or 2 times during last 7 days |

| 1 | Supervision – Oversight, encouragement or cueing provided 3 or more times during last 7 days – OR – Supervision (3 or more times) plus physical assistance provided only 1 or 2 times during last 7 days |

| 2 | Limited assistance – Resident highly involved in activity; received physical help in guided maneuvering of limbs or other non-weight bearing assistance 3 or more times – OR – More help provided only 1 or 2 times during last 7 days |

| 3 | Extensive assistance – While resident performed part of activity, over last 7-day period, help of following type(s) provided 3 or more times: –Weight-bearing support –Full staff performance during part (but not all) of last 7 days |

| 4 | Total dependence – Full staff performance of activity during entire 7 days |

From Minimum Data Set (MDS) - Version 2.0, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, September 2000

We used beneficiary summary files and MDS assessments to determine residents’ demographic characteristics. Medicare data, prior MDS assessments, and the Chronic Condition Warehouse data furnished by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services were used to determine comorbid diagnoses present before the amputation. We calculated the Charlson Comorbidity Index(10) based on both prior and hospital diagnoses to represent each resident’s overall comorbid burden. The Charlson Index assigns from 1 to 6 points to 16 comorbid conditions such as heart disease, dementia, and cancer, based on the mortality risk associated with each. The sum ranges from 0, for a person with no comorbidities, to 33 for an individual with the severest form of all included conditions.

Population

We included the first qualifying stay for residents with an inpatient admission during which an amputation was performed. The following ICD-9 procedure codes were used to select TM, BK, and AK amputations, respectively: 84.12, 84.15, and 84.17 (disarticulations of the ankle or knee were too rare to include). Because coding makes it impossible to determine the number of limbs involved, admissions with prior AK procedures were excluded, as were admissions with multiple amputations. We excluded admissions during which a stroke occurred and admissions with a stroke in the previous six months because stroke has a substantial and lasting effect on ADLs.(11) Qualifying stays had at least one MDS assessment within 60 days prior to hospital admission, hospital length of stay of 1-30 days, admission on or after May 1, 2006, and discharge before August 1, 2007. We included residents who were at least 67 years of age as of January 1, 2006 so we would have two years of prior Medicare data to provide information on comorbid conditions; there was no upper cutoff for age. We excluded residents with HMO membership during 2006-2007 (HMOs do not report hospital data); residents less than 67 years old as of January 1, 2006; residents with no record in the 2006-2007 beneficiary summary files; residents with no Medicare Part A coverage for either year; residents with more than 20 hospital stays in 2006-2007; and residents who died in the hospital.

Statistical analysis

We used SAS for Windows, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for all analyses. Characteristics of residents who received the three types of amputations were compared using chi-square analysis. Residents’ demographic characteristics, type of procedure, pre-hospital diagnoses, cognitive performance, Charlson Comorbidity Index(10), and baseline ADL score were included as independent variables in a linear mixed model of ADL performance. The Charlson Index reflected both previous and current diagnoses. Because few residents (2.5%) had a Charlson Index(10) over 10, we truncated it at 10 for modeling. To accommodate variation in the number and timing of individual’s ADL measurements, the ADL intercept and slope were treated as both fixed and random effects.(12) Time since hospital discharge was measured in months. Initially, the model included all two- and three-way interaction terms involving time and procedure type as well as selected covariates (demographic characteristics, prior health care utilization). We retained covariates and interaction terms that remained statistically significant, as well as acute myocardial infarction and chronic kidney disease.

Because truncating residents’ ADL trajectories due to either death or readmission could represent informative dropout, we also tested a shared parameter model,(13) where ADL trajectory and time to dropout were modeled simultaneously. The parameter estimates from the two modeling strategies were very similar, therefore we present results from only the simpler mixed model.

Results

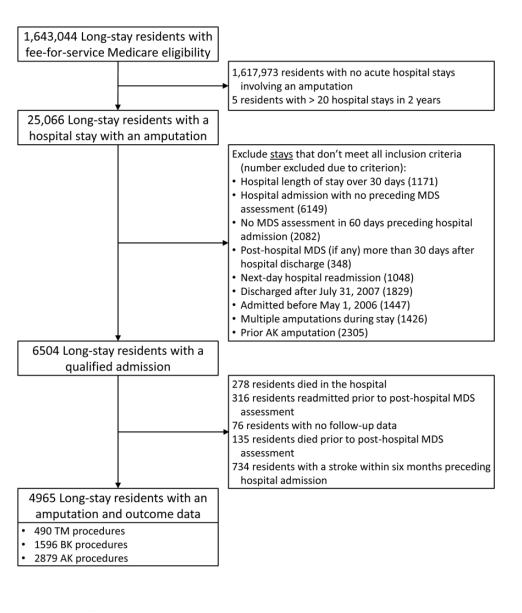

Derivation of the analytic sample is shown in Figure 1. Of the 25,066 long-stay residents who had an amputation during the study period, we excluded 18,562 with no qualifying admission, primarily because there was no pre-hospital MDS, the resident had a prior AK amputation, or the timing of the hospital stay did not allow for sufficient follow-up. We further excluded 1539 residents with a stroke in the prior six months, who died in the hospital, or who lacked sufficient follow-up data. We identified 4965 residents who met inclusion criteria – 490 received a TM procedure, 1596 received a BK procedure, and 2879 received an AK procedure (Table I). Over half were women (54.0%), with women overrepresented in the AK group (58.0%, P < .001). Less than half (45.3%) were 76 to 85 years of age; patients older than 85 were more likely to receive AK procedures than younger patients (P < .001). Most residents had at least moderate ADL impairment (11-20) on their last pre-hospital assessment; only 9.9% scored less than 11 on the 28-point ADL scale. Just over half had no to mild cognitive impairment (CPS 0-2; 53.6%), and 34.7% had moderate impairment (CPS 3-4). Residents who had AK procedures had worse baseline ADL and CPS scores than the other two groups (both P < .001). Chronic comorbidities were common – over half of the residents had diabetes (70.7%), coronary heart disease (57.1%), congestive heart failure (52.1%), and/or chronic kidney failure (53.6%). All of these diagnoses were less prevalent in the AK group (all P < .001).

Figure 1.

Derivation of study cohort from population of long-stay nursing home residents who were Medicare eligible, 2006-2007. MDS=Minimum Data Set, TM=trans metatarsal, BK=below knee, AK=above knee.

Table I.

Characteristics of Long-stay Nursing Home Residents who were Hospitalized for an Amputation [Number (Percent of procedure type)].a

| Procedure type |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | TM (N=490) |

BK (N=1596) |

AK (N=2879) |

Total (N=4965) |

P- valueb |

| Demographics | |||||

| Sex | < .001 | ||||

| Female | 240 (49.0) | 773 (48.4) | 1669 (58.0) | 2682 (54.0) | |

| Male | 250 (51.0) | 823 (51.6) | 1210 (42.0) | 2283 (46.0) | |

| Age | < .001 | ||||

| 67 to 75 | 161 (32.9) | 509 (31.9) | 666 (23.1) | 1336 (26.9) | |

| 76 to 85 | 227 (46.3) | 744 (46.6) | 1276 (44.3) | 2247 (45.3) | |

| 86 and older | 102 (20.8) | 343 (21.5) | 937 (32.6) | 1382 (27.8) | |

| Racec | |||||

| Black | 93 (19.0) | 375 (23.5) | 845 (29.4) | 1313 (26.4) | < .001 |

| Hispanic | 32 (6.5) | 75 (4.7) | 130 (4.5) | 237 (4.8) | |

| White | 357 (72.9) | 1107 (69.4) | 1863 (64.7) | 3327 (67.0) | |

| Unknown | 8 (1.6) | 39 (2.4) | 41 (1.4) | 88 (1.8) | |

| Activities of Daily Living score (pre- hospital) |

< .001 | ||||

| 0-10 | 104 (21.2) | 183 (11.5) | 203 (7.0) | 490 (9.9) | |

| 11-15 | 106 (21.6) | 300 (18.8) | 321 (11.2) | 727 (14.6) | |

| 16-20 | 179 (36.5) | 640 (40.1) | 847 (29.4) | 1666 (33.6) | |

| 21-28 | 101 (20.6) | 473 (29.6) | 1508 (52.4) | 2082 (41.9) | |

| Cognitive Performance Score (pre- hospital) |

< .001 | ||||

| Not/mildly impaired, CPS 0-2 | 365 (74.5) | 1057 (66.2) | 1241 (43.1) | 2663 (53.6) | |

| Moderately impaired, CPS 3-4 | 102 (20.8) | 455 (28.5) | 1167 (40.5) | 1724 (34.7) | |

| Severely impaired, CPS 5-6 | 23 (4.7) | 84 (5.3) | 471 (16.4) | 578 (11.6) | |

| Prior healthcare utilization | |||||

| Hospital stays during previous 6 months |

< .001 | ||||

| 0 | 57 (11.6) | 235 (14.7) | 740 (25.7 | 103 220.8 | |

| 1 | 172 (35.1) | 485 (30.4) | 911 (31.6 | 156 831.6 | |

| 2 or more | 261 (53.3) | 876 (54.9) | 1228 (42.7 | 2365 47.6 | |

| Diagnoses prior to hospital admission |

|||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 46 (9.4) | 162 (10.2) | 226 (7.8) | 434 (8.7) | .029 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 283 (57.8) | 979 (61.3) | 1399 (48.6) | 2661 (53.6) | < .001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 287 (58.6) | 889 (55.7) | 1411 (49.0) | 2587 (52.1) | < .001 |

| Coronary heart disease | 313 (63.9) | 983 (61.6) | 1538 (53.4) | 2834 (57.1) | < .001 |

| Diabetes | 394 (80.4) | 1258 (78.8) | 1857 (64.5) | 3509 (70.7) | < .001 |

| End stage renal disease | 86 (17.6) | 244 (15.3) | 226 (7.8) | 556 (11.2) | < .001 |

| Stroke/Transient Ischemic Attack | 119 (24.3) | 414 (25.9) | 1056 (36.7) | 1589 (32.0) | < .001 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (prior and current diagnoses) |

< .001 | ||||

| 0-3 | 98 (20.0) | 306 (19.2) | 926 (32.2) | 1330 (26.8) | |

| 4-5 | 132 (26.9) | 407 (25.5) | 820 (28.5) | 1359 (27.4) | |

| 6-8 | 186 (38.0) | 676 (42.4) | 846 (29.4) | 1708 (34.4) | |

| 9 or more | 74 (15.1) | 207 (13.0) | 287 (10.0) | 568 (11.4) | |

| Hospital length of stay (days) | < .001 | ||||

| Less than 2 days | 14 (2.9) | 12 (0.8) | 28 (1.0) | 54 (1.1) | |

| 2 to 5 days | 96 (19.6) | 418 (26.2) | 820 (28.5) | 1334 (26.9) | |

| 6 to 10 days | 166 (33.9) | 550 (34.5) | 1070 (37.2) | 1786 (36.0) | |

| Over 10 days | 214 (43.7) | 616 (38.6) | 961 (33.4) | 1791 (36.1) | |

| MDS assessments following hospital discharge |

.013 | ||||

| One | 155 (31.6) | 411 (25.8) | 730 (25.4) | 1296 (26.1) | |

| Two or more | 335 (68.4) | 1185 (74.2) | 2149 (74.6) | 3669 (73.9) | |

Column percents don’t always add up to 100% due to rounding error.

Chi-square analysis comparing the three amputation level groups.

Version 2 of the MDS is limited to these categories for race and ethnicity.

Most residents (79.2%) had been hospitalized during the previous six months, with the AK group having fewer prior hospitalizations. More residents in the TM group had hospital stays of at least 11 days then either the BK (38.6%) or AK (33.4%) groups (P < .001). Mean length of stay was 9.7 days overall, with longest mean stay in the TM group (10.9 days).

The post-hospital ADL trajectories model is shown in Table II. “Factors affecting the amount of ADL change” can be interpreted as changes in the trajectory’s intercept – they either increase or decrease the ADL score by a fixed amount. Because higher scores indicate greater need for assistance with ADLs, positive coefficients indicate worse ADL impairment. For each additional point on the ADL score prior to hospitalization, post-hospital scores were 0.45 points higher (P < .001). Higher CPS scores were similarly associated with higher post-hospital ADL impairment (P < .001). Post-hospital ADL scores were somewhat better for men than women, while greater age and hospital length of stay were associated with higher post-hospital ADL impairment. Stroke, end-stage renal disease and diabetes were associated with worse post-hospital ADL scores, while residents with coronary heart disease did somewhat better following hospitalization. Relative to TM procedures, BK and AK procedures were associated with worse ADL scores (1.33 and 1.83 points, respectively). We retained the acute myocardial infarction variable despite its non-significance (P = .95) because its interaction with time was very close to being statistically significant (P = .055).

Table II.

Hierarchical linear model of ADL trajectories following amputation, adjusted for procedure type, baseline ADL and cognition, demographic characteristics, and comorbid diagnoses.a

| Variable | Parameter estimate (95% Confidence interval) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 10.25 | (9.80 – 10.69) | <.001 |

| Factors affecting the amount of ADL change (intercept) |

|||

| Baseline ADL score (0 to 28) | 0.45 | (0.43 – 0.46) | <.001 |

| Cognitive Performance Score (0 to 6) | 0.52 | (0.46 – 0.58) | <.001 |

| Sex (male=1, female=0) | −0.37 | (−0.56 - −0.18) | <.001 |

| Age (centered at mean of 80.7 years) | 0.06 | (0.05 – 0.07) | <.001 |

| Hospital length of stay (centered at median of 8 days) |

0.09 | (0.07 – 0.10) | <.001 |

| Pre-hospital diagnoses | |||

| Acute myocardial infarction | −0.01 | (−0.35 – 0.33) | .95 |

| Stroke | 0.51 | (0.30 – 0.71) | <.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | −0.18 | (−0.38 – 0.02) | .078 |

| End-stage renal disease | 0.61 | (0.29 – 0.92) | <.001 |

| Coronary heart disease | −0.31 | (−0.51 - −0.11) | .002 |

| Diabetes | 0.22 | (0.01 – 0.44) | .040 |

| Type of procedure | |||

| Below knee | 1.33 | (0.99 – 1.67) | <.001 |

| Above knee | 1.83 | (1.50 – 2.16) | <.001 |

| Factors affecting the rate of ADL change (slope) | |||

| Time (months) | −1.06 | (−1.27 - −0.85) | <.001 |

| Acute myocardial infarctionb | −0.20 | (−0.40 – 0.00) | .055 |

| Prior strokeb | 0.26 | (0.15 – 0.37) | <.001 |

| Coronary heart diseaseb | −0.16 | (−0.26 - −0.05) | .004 |

| BK procedure (compared with TM)b | 0.32 | (0.10 – 0.54) | .005 |

| AK procedure (compared with TM)b | 0.67 | (0.46 – 0.89) | <.001 |

“Factors affecting the amount of ADL change” can be interpreted as changes in the trajectory’s intercept, increasing or decreasing the ADL score by a fixed amount. “Factors affecting the rate of ADL change” can be interpreted as the overall slope of the ADL trajectory (Time), or changes to the slope (interaction terms).

Interaction of this variable with time.

ADL=Activities of Daily Living, BK=below knee, AK=above knee, TM=trans metatarsal

“Factors affecting the rate of ADL change” in Table II are interpreted as the slope of the ADL trajectory, or changes to the slope. The overall slope (Time), -1.06 points per month, represents the average rate of change in ADL score, excluding the effects of diagnoses with interaction terms. Thus, residents’ ADL scores improve approximately one point per month after the hospital stay. Other coefficients add or subtract from this value. For example, acute myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease both are associated with more negative slopes, indicating that they are associated with faster improvement, while stroke more than six months before hospitalization has a positive coefficient and is therefore associated with slower improvement. Relative to TM procedures, BK slows ADL recovery by 0.32 points per month while AK slows ADL recovery by 0.67 points per month.

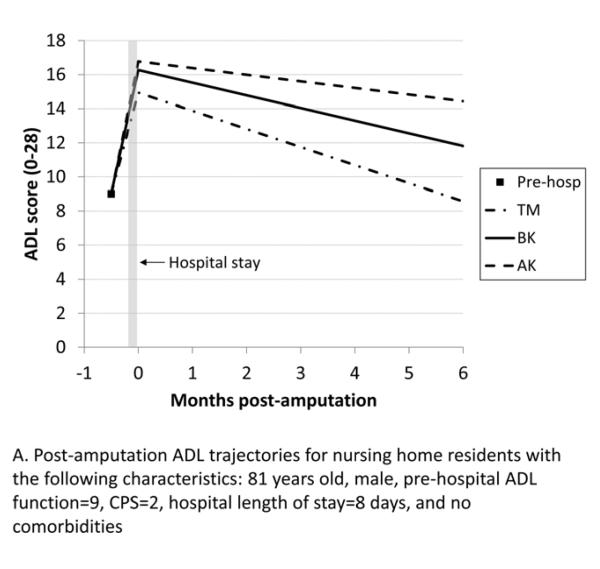

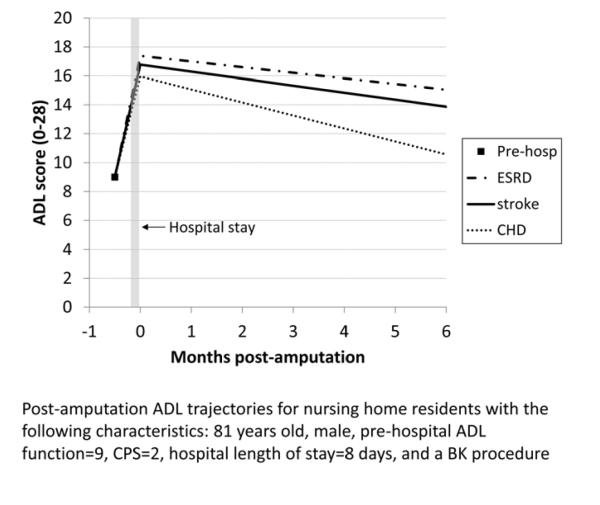

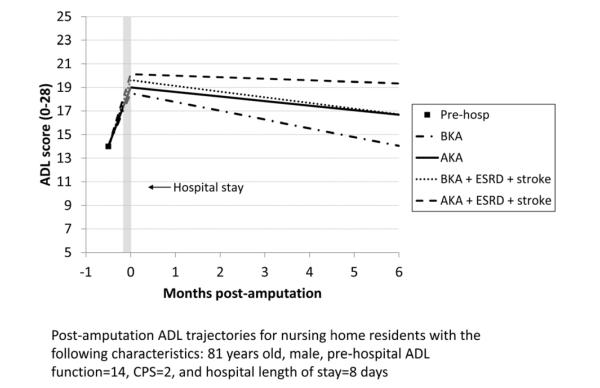

Figure 2 shows the expected ADL trajectories for hypothetical groups of patients based on the model in Table II. Because of the interaction terms in the model, the combined effects of procedure and covariates on residents’ ADL trajectories can only be visualized for specific groups of residents. From a moderately impaired pre-hospital ADL score of 9, all residents show worsened ADL scores following hospitalization, with the AK group having the greatest change. On average, the ADL trajectories for all residents subsequently improve, with only the TM group returning to baseline in six months. The ADL trajectory shows greater improvement for the BK group compared with the AK group, but neither group returns to their pre-hospital ADL level. Figure 3 compares ADL trajectories for a group of residents who had a BK procedure, changing the comorbidities that are present while holding other variables constant. The residents with a history of stroke or ESRD improved more slowly after hospitalization than residents who did not have a history of stroke or ESRD, while residents with coronary heart disease improved somewhat faster. Figure 4 depicts the expected ADL trajectories for a hypothetical group of patients showing the effect of varying amputation level and comorbid diagnoses while holding other characteristics constant. Patients with a history of ESRD and stroke undergoing BKA had similar functional trajectories as patients undergoing an AKA who did not have those comorbidities.

Figure 2.

Post-amputation ADL trajectories for hypothetical groups of nursing home residents with the following characteristics: 81 years old, male, pre-hospital ADL score=9, CPS=2, hospital length of stay=8 days, and no comorbidities. The 3 lines show the effect of varying procedure type while holding other characteristics constant. ADL=Activities of Daily Living, CPS=Cognitive Performance Score, TM=trans metatarsal, BK=below knee, AK=above knee.

Figure 3.

Post-amputation ADL trajectories for hypothetical nursing home residents with the following characteristics: 81 years old, male, pre-hospital ADL score=9, CPS=2, hospital length of stay=8 days, and a BK procedure. The 3 lines show the effect of varying comorbid diagnoses while holding other characteristics constant. ADL=Activities of Daily Living, CPS=Cognitive Performance Score, BK=below knee, ESRD=end stage renal disease, CHD=coronary heart disease.

Figure 4.

Post-amputation ADL trajectories for nursing home residents with the following characteristics: 81 years old, male, pre-hospital ADL score=14, CPS=2, and hospital length of stay=8 days. The 4 lines show the effect of varying amputation level and comorbid diagnoses while holding other characteristics constant. ADL=Activities of Daily Living, CPS=Cognitive Performance Score, BKA=below knee amputation, AKA=above knee amputation, ESRD=end-stage renal disease.

Discussion

We evaluated the functional status of nursing home residents after amputation, using ADL scores to depict functional trajectories. Elderly nursing home residents undergoing BK and AK amputations failed to return to their functional baseline within six months. BK amputation had a better functional trajectory compared to AK amputation suggesting that limb preservation is of benefit, even in this frail cohort. ESRD, stroke, and poor cognitive performance scores were associated with poor functional outcomes after an amputation and may be considered as indications for performing an AKA based on the equivalently poor trajectories for BKAs.

With increased interest in evaluating utilization and outcomes, the ability to assess functional outcomes is of significance in managing elderly patients. Evaluation of non-traditional outcome measures such as expected functional trajectory are useful tools in the decision-making process for elderly patients requiring an amputation, and may allow physicians and patients to make more informed choices for their procedures. Previous studies have evaluated post-hospital ADL trajectories in nursing home residents, including those with hip fracture, CHF, stroke, pneumonia, and sepsis, and have demonstrated that except for residents with hip fracture, residents with acute hospitalizations for several other diagnoses do not return to baseline function within six months of hospital discharge.(11)

Other authors have evaluated functional outcome of patients who underwent amputation. Suckow et al. evaluated 436 patients who subsequently received an above-knee (AK), below-knee (BK), or minor amputation after lower extremity bypass. They reported that patients most likely to remain ambulatory were those living at home preoperatively. They documented the presence of several comorbidities associated with patients less likely to achieve a good functional outcome, including coronary disease, dialysis, and congestive heart failure.(14) This analysis found similar results regarding comorbidities in that pre-hospital diagnoses of end-stage renal disease (ESRD), stroke, and diabetes were significantly associated with inferior functional trajectories after amputation. Nehler et al. evaluated the functional history of patients undergoing major amputation in an academic vascular surgery practice and concluded that the ability to predict ambulation after BKA in the vascular population is poor.(15) Frykberg et al. described that major lower extremity amputation in the patients 80 years of age and above was associated with a considerable mortality and deterioration of functional and residential status.(16) They reported that postoperative functional status remained unchanged in 40% and worsened in 55% of patients. We have demonstrated in nursing home residents that functional status did not return to baseline by six months following amputation. Other authors have stated that when preservation of function is the chief concern, amputation should be performed at the lowest possible level.(17) Suckow et al. reported by life-table analysis at 1 year, that the proportion of surviving patients with a good functional outcome varied by the presence and extent of amputation (proportion surviving with good functional outcome = 88% no amputation, 81% minor amputation, 55% BK amputation, and 45% AK amputation, p = 0.001).(14) This study demonstrated similar findings for nursing home residents in that there was significant benefit to limb preservation. This study has also demonstrated the importance of baseline function and cognitive status as a predictor of functional outcomes in the nursing home population. Poor baseline ADL function and poor baseline cognitive performance scores were significantly associated with poor functional trajectories after amputation. Other authors have described significant predictors of poor functional outcome were impaired ambulatory ability at the time of presentation and the presence of dementia.(18) One theory for this is that hospitalized older adults are often discharged with ADL function that is worse than their pre-hospital function, and hospitalization-associated disability can occur despite successful treatment of the admission-triggering illness.(19) As well, others have suggested that post-amputation rehabilitation is physically and cognitively demanding and those neuropsychological and clinical variables predict a large amount of 6 month outcome variance. Cognitive difficulties may be considered mediators of poor outcome.(20) This analysis demonstrates that baseline cognitive scores and ADL scores were associated with poor functional trajectories after amputation and may be considered in the patients requiring amputation as a tool to evaluate future functional trajectories.

Other factors which were found to be associated with poor functional trajectories after amputation included age and gender.. Authors have evaluated the function occurring before and after hospital admission for medical illness and reported that oldest patients are at high risk of poor functional outcomes as they are less likely to recover ADL function that they lost before admission and more likely to develop new functional deficits during their hospitalization.(21) We also discovered that women had worse ADL function after amputation compared to men. Armstrong et al. evaluated a New York State database for 14,555 nontraumatic amputations and concluded that when controlling for age, prevalence of vascular disease was not significantly different by gender in diabetic and nondiabetic groups at all amputation levels.(22) That being stated, little evaluation has been performed on gender disparity and function after amputation. Functional ability and social dependence were investigated by personal interview of 107 lower limb amputees surviving 1-5 years postoperatively. Above-knee or bilateral amputation and postoperative pain were associated with reduced functional ability and no significant association was found with cause of operation or sex of the amputees.(23). In this analysis female gender and age were significantly associated with inferior trajectories after amputation at any level.

With regard to comorbidities, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), diabetes, and stroke were found to be significantly associated with inferior function after amputation, where acute myocardial infarction was not associated with poor functional trajectories. Previous studies utilizing ADL data have demonstrated among nursing home residents with ESRD, the initiation of dialysis was associated with a substantial and sustained decline in functional status. As well, lower-extremity disease was found to be twice as high among individuals with diabetes.(24) This analysis has demonstrated that ESRD, previous stroke, and diabetes mellitus are associated with poorer functional outcomes than in patients without these diagnoses. Hypothetical models created and presented in this analysis demonstrate that a BKA may not be the procedure of choice when these comorbidities are combined based on their poor functional trajectory.

This analysis has several limitations. We analyzed a large, national cohort of long-stay nursing home residents, which is a highly selected cohort, and results may not generalize to other populations of frail, older adults. Linking nursing home assessments to Medicare data provided more information on diagnoses than is available on the MDS alone. However, the timing of MDS assessments and hospital stays required us to exclude many residents to provide adequate data before and after hospitalization for meaningful analysis. While we restricted our cohort to those hospitalized for amputation procedures, the coding schemes from different hospitals could be variable. Given that we excluded patients who were readmitted before an MDS assessment was performed, it is possible that healthier patients are over-represented in the post-hospital trajectories. However, a shared parameter model with death and readmission produced essentially the same results, suggesting that drop-out was not informative. Finally, it is possible that the differences between patients who received either different levels of amputation may have affected model results.

In conclusion, AKA and BKA amputations among Medicare-eligible nursing home residents were associated with similar initial declines in functional status. While neither functional trajectory returned to baseline at six months after the procedure, BKA had superior trajectories in this population compared to AKA. Functional status after amputation in nursing home residents is multifactorial beyond procedure type, and this analysis has demonstrated worse functional trajectories after intervention were associated with female gender, poor baseline cognitive performance and poor baseline ADL scores. As well, comorbid conditions including ESRD and history of stroke were associated with significantly inferior trajectories and these patients may benefit from an AKA as their trajectories are the worst. The findings of this analysis highlight the importance of considering premorbid conditions, cognitive status, and baseline ADL function prior to amputation in nursing home residents. These data may assist providers and patients about the trajectory and time course of changes in functional status after amputation and physicians the opportunity to make more patient-centered outcomes decisions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01AG028476. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented at Midwestern Vascular, 37th Annual Meeting, September 6-8, 2013, Chicago, IL Corresponding Author: Todd R. Vogel, MD, MPH, Department of Surgery, Division of Vascular Surgery, University of Missouri Hospital & Clinics, One Hospital Drive, Columbia, MO 65212

References

- 1.Gillen P, Spore D, Mor V, Freiberger W. Functional and residential status transitions among nursing home residents. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1996;51(1):M29–36. doi: 10.1093/gerona/51a.1.m29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehr DR, Binder EF, Kruse RL, Zweig SC, Madsen R, Popejoy L, et al. Predicting mortality in nursing home residents with lower respiratory tract infection: The Missouri LRI Study. JAMA. 2001;286(19):2427–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.19.2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manton KG. A longitudinal study of functional change and mortality in the United States. J Gerontol. 1988;43(5):S153–61. doi: 10.1093/geronj/43.5.s153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rantz MJ, Popejoy L, Zwygart-Stauffacher M, Wipke-Tevis D, Grando VT. Minimum Data Set and Resident Assessment Instrument. Can using standardized assessment improve clinical practice and outcomes of care? J Gerontol Nurs. 1999;25(6):35–43. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19990601-08. quiz 54-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris JN, Fries BE, Morris SA. Scaling ADLs within the MDS. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54(11):M546–53. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.11.m546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawes C, Morris JN, Phillips CD, Mor V, Fries BE. Nonemaker S. Reliability estimates for the Minimum Data Set for nursing home resident assessment and care screening (MDS). Gerontologist. 1995;35(2):172–8. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.2.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carpenter GI, Hastie CL, Morris JN, Fries BE, Ankri J. Measuring change in activities of daily living in nursing home residents with moderate to severe cognitive impairment. BMC Geriatr. 2006;6:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McConnell ES, Pieper CF, Sloane RJ, Branch LG. Effects of cognitive performance on change in physical function in long-stay nursing home residents. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(12):M778–84. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.12.m778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, Hawes C, Phillips C, Mor V, et al. MDS Cognitive Performance Scale. J Gerontol. 1994;49(4):M174–82. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.4.m174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kruse RL, Petroski GF, Mehr DR, Banaszak-Holl J, Intrator O. Activity of daily living trajectories surrounding acute hospitalization of long-stay nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(11):1909–18. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singer JD, Willett JB, Oxford University Press . Applied longitudinal data analysis modeling change and event occurrence. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press; New York ; Oxford: 2003. p. 644. online resource (xx. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henderson R, Diggle P, Dobson A. Joint modelling of longitudinal measurements and event time data. Biostatistics. 2000;1(4):465–80. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/1.4.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suckow BD, Goodney PP, Cambria RA, Bertges DJ, Eldrup-Jorgensen J, Indes JE, et al. Predicting functional status following amputation after lower extremity bypass. Ann Vasc Surg. 2012;26(1):67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nehler MR, Coll JR, Hiatt WR, Regensteiner JG, Schnickel GT, Klenke WA, et al. Functional outcome in a contemporary series of major lower extremity amputations. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38(1):7–14. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frykberg RG, Arora S, Pomposelli FB, Jr., LoGerfo F. Functional outcome in the elderly following lower extremity amputation. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1998;37(3):181–5. doi: 10.1016/s1067-2516(98)80107-5. discussion 261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waters RL, Perry J, Antonelli D, Hislop H. Energy cost of walking of amputees: the influence of level of amputation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58(1):42–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor SM, Kalbaugh CA, Blackhurst DW, Cass AL, Trent EA, Langan EM, 3rd, et al. Determinants of functional outcome after revascularization for critical limb ischemia: an analysis of 1000 consecutive vascular interventions. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44(4):747–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.06.015. discussion 55-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston CB. Hospitalization-associated disability: "She was probably able to ambulate, but I'm not sure". JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Neill BF, Evans JJ. Memory and executive function predict mobility rehabilitation outcome after lower-limb amputation. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(13):1083–91. doi: 10.1080/09638280802509579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, Counsell SR, Stewart AL, Kresevic D, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):451–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armstrong DG, Lavery LA, van Houtum WH, Harkless LB. The impact of gender on amputation. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1997;36(1):66–9. doi: 10.1016/s1067-2516(97)80014-2. discussion 81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helm P, Engel T, Holm A, Kristiansen VB, Rosendahl S. Function after lower limb amputation. Acta Orthop Scand. 1986;57(2):154–7. doi: 10.3109/17453678609000891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gregg EW, Sorlie P, Paulose-Ram R, Gu Q, Eberhardt MS, Wolz M, et al. Prevalence of lower-extremity disease in the US adult population >=40 years of age with and without diabetes: 1999-2000 national health and nutrition examination survey. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(7):1591–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.7.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]