Abstract

Implanted materials including drug delivery devices and chemical sensors undergo what is termed the foreign body reaction (FBR). Depending on the device and its intended application, the FBR can have differing consequences. An extensive scientific research effort has been devoted to elucidating the cellular and molecular mechanisms that drive the FBR. Important, yet relatively unexplored, research includes the localized tissue biochemistry and the chemical signaling events that occur throughout the FBR. This review provides an overview of the mechanisms of the FBR, describes how the FBR affects different implanted devices, and illustrates the role that microdialysis sampling can play in further elucidating the chemical communication processes that drive FBR outcomes.

1.0 Introduction

Microdialysis sampling has been used to address many diverse basic and clinical research problems (Müller, 2013; Robinson et al., 1991; Westerink and Cremers, 2007). The extensive efforts of Dr. Urban Ungerstedt to promote creative thought in the uses of the microdialysis sampling technique to allow for studies he termed “tissue biochemistry” have resulted in many diverse sampling applications in living systems (Lunte et al., 1991; Ungerstedt, 1991). The diversity of solutes that have been collected from the extracellular fluid space (ECS) using microdialysis sampling include classical neurotransmitters (Robinson et al., 1991), energy metabolites including glucose and lactate (Benveniste et al., 1987; Lonnroth et al., 1987), pharmaceutical compounds (de Lange et al., 1994; Elmquist and Sawchuk, 1997; Hammarlund-Udenaes, 2000), trace metals (Su et al., 2008), neuropeptides (Kendrick, 1990; Wotjak et al., 2008), and signaling proteins including cytokines (Ao and Stenken, 2006; Clough, 2005).

Over the past decade, our research group has been interested in using microdialysis sampling as a method to monitor different chemical events that occur during a process known as the foreign body reaction (FBR) (Figure 1). We have been specifically interested in this topic from an analytical chemistry standpoint since the FBR seriously affects the data reliability from implanted sensors, particularly glucose sensors implanted into the subcutaneous space (Wilson and Gifford, 2005). The FBR is a complex, multi-step process, including wound healing, that occurs to resolve injury in response to any implanted object. The FBR is a dynamic continuum of biochemical and cellular changes (Anderson et al., 2008); therefore, monitoring the spatiotemporal evolution of cell types present at the foreign body site and their localized chemical communication through the ECS environment surrounding the implanted material is necessary to elucidate mechanisms that may alter FBR outcomes. Since microdialysis sampling has previously been used to monitor different chemical events, this sampling technique is ideal for elucidating FBR molecular mechanisms.

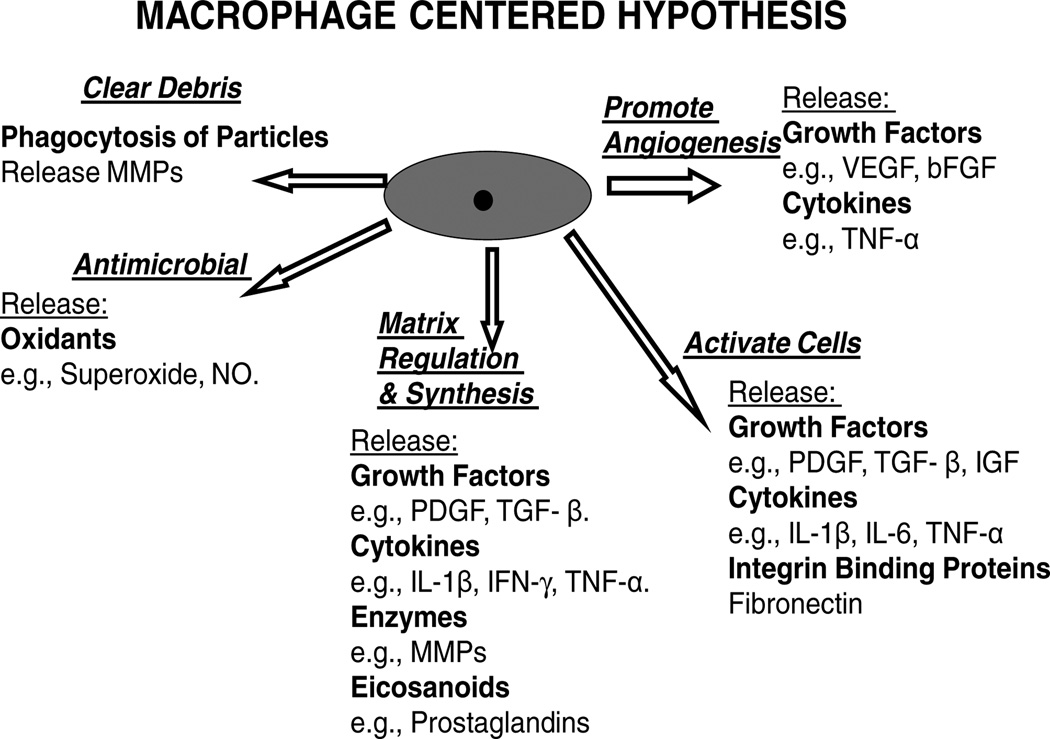

Figure 1.

Macrophage chemical products released during the healing phase of the foreign body response.

2.0 Foreign Body Reaction (FBR)

As early as the 1970s, the FBR was hypothesized to be a chronic inflammatory response (Coleman et al., 1974). During the FBR, implanted objects or biomaterials are recognized in the body as unwanted, foreign objects that must be destroyed or walled-off from healthy tissue (Castner and Ratner, 2002). In addition to attempting to rid the perceived invading biomaterial, the cascade of events in wound healing and the FBR processes aim to restore function to the site by preventing infection and repairing tissue.

Characteristic stages recognized for the FBR in response to a biomaterial are protein adsorption, cell recruitment (including monocyte/macrophage adhesion, foreign body giant cell formation, and inflammatory/wound healing cell presence), extracellular matrix formation, and fibrosis. The molecular and cellular interactions, including elaborate, successive immune pathways, are distinct for each phase of the FBR, thereby making the unique molecular mechanisms of each stage attractive and ideal for pharmaceutical and clinical research involving microdialysis sampling. Upon implantation of the biomaterial, a layer of plasma proteins forms, adheres to the implant, and dictates the recruitment and adhesion of inflammatory cells, which subsequently direct the wound healing process (Junge et al., 2012). This is followed by an intricate progression of successive, yet overlapping phases, including inflammation, reepithelialisation/angiogenesis, and extracellular matrix remodeling (Cardoso et al., 2011; Gurtner et al., 2008; Heydari Nasrabadi, 2011; Janis et al., 2010; Nilani P., 2011; Rodero and Khosrotehrani, 2010).

Contrary to physiological wound healing and scar formation, the FBR resulting from the implant of a biomaterial persists for the in vivo lifetime of the implanted device due to cellular interactions at the biomaterial/tissue interface (Anderson et al., 2008; Junge et al., 2012). The degree of the cellular activity, and thus the FBR, at this interface directly corresponds to the extent of fibrosis induced. Fibrosis occurs when the rate of collagen formation exceeds the rate at which it is degraded (Wynn, 2008). Typical tissue reconstruction is replaced by a fibrotic encapsulation of the foreign body in an effort to segregate the object from the surrounding tissue as illustrated for a microdialysis probe in Figure 2. A collagenous bag forms around the implanted biomaterial through the role of growth factors and other cellular mediators secreted by macrophages, foreign body giant cells, neutrophils, and fibroblasts, .

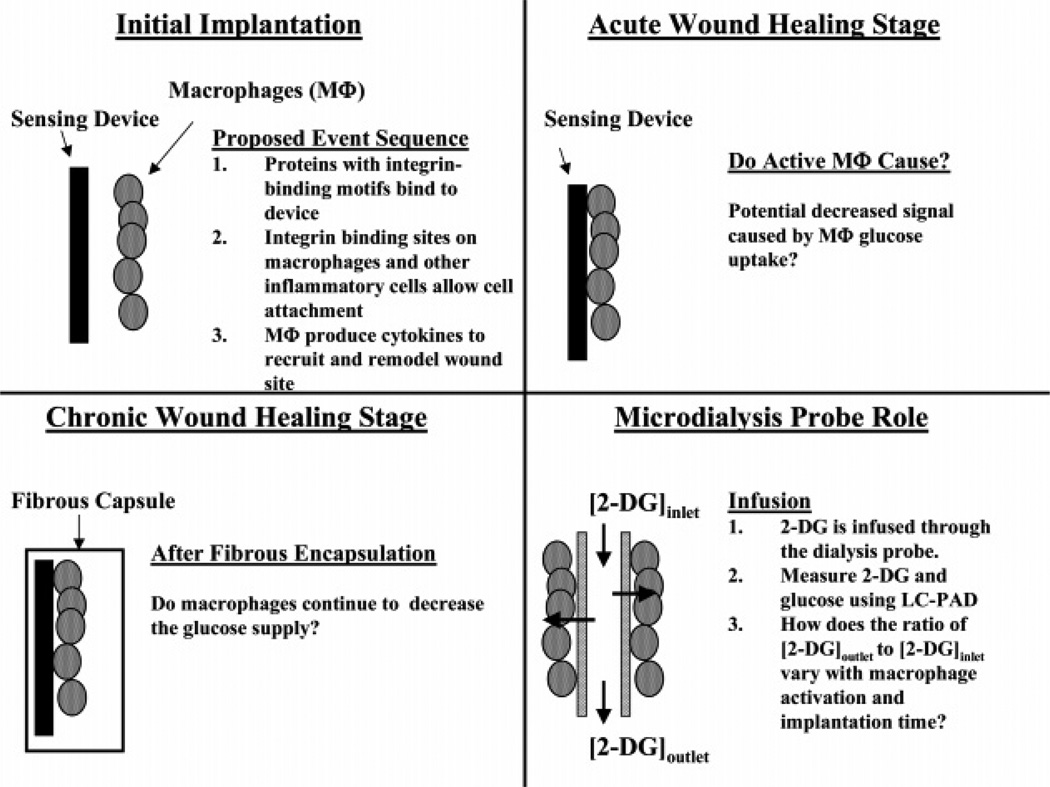

Figure 2.

Stages of wound healing. The microdialysis probe can be used with internal standards to test different aspects of the tissue biochemistry. Reprinted with permission from Analytical Chemistry 78(22): 7778–7784. Copyright 2006 American Chemical Society.

While biomaterials research has fervently studied the biochemical, cellular, and immunological dynamics that drive the FBR in response to different implanted materials, a significant portion of the research is concerned with biomaterial properties. The extent of the elicited FBR is influenced by the biomaterials’ chemical (i.e. hydrophilic, hydrophobic, or charged surfaces), physical, and morphological (i.e. porosity and roughness) properties. For example, the surface chemistry of a biomaterial modulates the secretion of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) from adherent macrophages (Jones et al., 2008). Research has shown that biomaterial surface properties significantly contribute to the extent of the FBR during the first two to four weeks after implantation (Anderson et al., 2008). Therefore, a biomaterial’s in vivo biocompatibility and functional longevity are determined chiefly by the consequential FBR. The different stages and resulting chemical production resulting from the FBR are outlined in more detail in the subsequent subsections.

2.1 Protein Adsorption

Blood-derived proteins adsorb onto all polymeric biomaterials after implantation. Many of these proteins, e.g., fibrinogen and fibronectin, contain specific amino acid motifs, e.g., RGD, that bind to important cell-surface receptors called integrins. Different cells (e.g., macrophages) bind to surfaces via their integrin receptors, which serve as cell surface cues. Integrin binding of inflammatory cells to the implanted material initiates a signaling cascade that directs the FBR (Bellis, 2011; Garcia, 2005; Perlin et al., 2008; von der Mark et al., 2010). This signaling cascade leads to transmission of inflammatory and recruiting chemical signals, recruitment of different inflammatory cells, and extracellular matrix restructuring via metalloproteinases enzymes.

2.2 Macrophages and other Immune-derived Cells

While the functions of different cell types involved in the various stages of the FBR have been investigated, the macrophage is a predominant cell that has attracted the most attention due to its role in significantly directing the FBR (Anderson and Miller, 1984; Anderson et al., 2008). The role of macrophages in the collective FBR tableau begins at the moment of perceived injury, including the implantation of a biomaterial. After any biomaterial is implanted, an immune response is coordinatedto diminish the injury and return the system to homeostasis (Vaday et al., 2001). During the FBR, the release of numerous chemicals such as oxidants, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and signaling agents (leukotrienes and cytokines) into the extracellular matrix from macrophages is responsible for various functions including destruction (or attempted destruction) of the alleged foreign object, degradation of the extracellular matrix to allow cellular migration, and cell-to-cell chemical communication. In wound healing, for example, inflammation alone is a biphasic process, involving both vascular and cellular responses, particularly the recruitment and infiltration of macrophages (Yi et al., 2012). The formulation of granulation tissue in reepithelialisation is not possible without macrophages, nor is dermal regeneration feasible without apoptosis of macrophages and their contemporary myofibroblasts and endothelial cells (Rodero and Khosrotehrani, 2010).

2.3 Cytokines

Cytokines are signaling proteins vital to driving the end result of the foreign body reaction by directing the inflammatory and wound healing responses (Anderson et al., 2008). Inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) induce MMP transcription, and MMPs begin clearing the ECM from inflammatory debris. The macrophage army will phagocytose debris, bacteria, and apoptotic neutrophils and will attempt to phagocytose the biomaterial foreign invader. Once it is understood that the foreign body enemy cannot be engulfed and destroyed, the macrophages enter a phase known as “frustrated phagocytosis” (Underhill and Goodridge, 2012). The secretion of cytokines and growth factors by activated macrophages and fibroblasts continue throughout wound healing and the FBR process. Cytokines, in turn, continue to recruit and activate leukocytes, neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages that steer the final wound healing and FBR processes.

Cytokines are potent, synergistic, transient, and highly localized soluble messenger proteins (~ 6 to 80 kDa) produced by inflammatory cells (e.g., lymphocytes, neutrophils, macrophages, and T-cells) that control nearly every aspect of immune responses (Gouwy et al., 2005). A single cytokine does not act alone; the network interactions of cytokines with one another may be accumulative, synergistic, or antagonistic, and the effects of one cytokine may induce the effect of another cytokine, thereby making the physiological effects of cytokines dependent on the relative concentrations of multiple cytokines. For this reason, it is often more important to determine the concentration and cytokine profile after an immune challenge rather than the concentration of a single cytokine. The combination of the cytokine and chemokine signal and their relative concentrations directs the cellular traffic to the implant site and is therefore critically important in orchestrating the FBR (Higgins et al., 2009; Rhodes et al., 1997).

Bead-based immunoassays for multiplexed cytokine measurement in low microliter volumes (typically 5 to 50 µL) are commercially available and have been extensively reviewed (Vignali, 2000). In addition to bead-based immunoassays, qRT-PCR (quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction) or gene arrays have been used to measure cytokine mRNA expression. Differences between all three types of assays have been reported in the literature (Ekerfelt et al., 2002).

2.4 Matrix metalloproteinases.(MMPs)

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a group of zinc-dependent proteases that cleave different extracellular matrix (ECM) components, allowing for cellular movement through the matrix and promotion of matrix remodeling. More than twenty MMPs have been identified and these enzymes are vastly important to clinical medicine (Stamenkovic, 2003) and biomaterials (Henninger et al., 2007; Jones et al., 2008; Khan et al., 2010; Luttikhuizen et al., 2006b; Tian and Kyriakides, 2009). MMPs break down the ECM, thereby releasing a variety of growth factors and soluble cytokines, which can then serve to recruit cells to rebuild the ECM after injury. Analytical methods for detection of clinically relevant MMPs ex vivo have been reviewed (Clark, 2001) and include bioassays or activity assays using labeled substrates, immunoassays and/or immunohistochemical staining, and zymography.

2.5 Arachidonic Acid Mediators – Leukotrienes and Prostaglandins

Macrophage activation leads to an increase in arachidonic acid metabolism and an increased production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and leukotriene B4 (LTB4), which are collectively called eicosanoids. The synergistic interactions between leukotrienes and cytokines (signaling proteins) and their influence on inflammatory cells have recently been described (Austen, 2008; Kim and Luster, 2007; Peters-Golden and Henderson, 2007). In sub-nanomolar (nM) concentrations, LTB4 is known to cause chemotaxis and chemokinesis in neutrophils. Measurement of eicosanoids in biological systems is challenging due to their hydrophobicity, low concentrations, and stability.

2.6 Reactive Oxygen Species

When activated, macrophages emit numerous chemicals including nitric oxide, superoxide, and hydrogen peroxide. In the context of implanted materials, these aggressive oxidants can degrade materials. Additionally, reactive oxygen species are of interest as they are indicators of inflammation and have been recently imaged using in vivo fluorescence-based imaging instruments (Liu et al., 2011; Selvam et al., 2011).

2.7 Foreign Body Reaction Assessment

Assessment of the progress or severity of the FBR is multi-faceted, and different chemical and cellular measurements have been described (Hunt et al., 1997). Cellular assessments have focused on discerning the population of leukocytes surrounding an implanted biomaterial that would normally be put into a stainless-steel cage (Marchant, 1989; Rodriguez et al., 2008). Additionally, these cell assessments have included further delineating different subpopulations among the immune cells at the implant site (Rhodes et al., 1997). Cytokine protein analysis of tissue in the presence of biomaterials has a significant history in biomaterials evaluation (Miller et al., 1989; Schutte et al., 2009). However, many cytokine measurements are performed by measuring mRNA, using PCR techniques rather than absolute protein measurements. What is clear, however, is that in vivo FBR assessments have moved from cellular analysis (e.g., types and numbers of cells adhered to the material such as macrophages, lymphocytes, or foreign body giant cells) to molecular detection of signaling proteins such as the cytokines and matrix remodeling proteins (Caplan and Shah, 2009; Luttikhuizen et al., 2006a).

3.0 Device and Implant Function Hindered by FBR Outcomes

Implantable chemical sensors and drug delivery devices have promising utility for continuous disease monitoring and therapy, particularly with respect to diabetes management (Desiss, 2006; Gilligan et al., 2004; Iyer et al., 2006). Obstacles and interactions marshaled by inherent processes and outcomes of the FBR, however, limit the purposed utility. Overcoming and manipulating the impediments are incumbent upon research striving to increase longevity, function, and, ultimately, the value of implanted sensors and devices.

3.1 Drug Delivery Devices

Implants aimed to deliver drugs and sensors implanted for glucose management in persons with diabetes can have their functions severely hindered by the fibrotic encapsulation that is a hallmark of the FBR. For drug delivery devices, the fibrotic capsule affects the diffusion of drug substances to vascularized tissue, thereby reducing delivery efficiency (Ratner, 2002). Ensuring angiogenesis around implanted drug or cell delivery is thus important to achieve appropriate dosing levels (Patel and Mikos, 2004). With an increasing interest and outlook for more delivery devices to release drugs to the systemic circulation and tissue engineering constructs that release different bioactive proteins or other solutes (Chertok et al., 2013), understanding how the FBR inhibits or interacts with these devices is a critical research area in the field of biomaterials (Voskerician et al., 2003).

3.2 Glucose Sensors

The field of drug delivery research is certainly much larger than that of implanted glucose sensors. However, since the FBR may hinder drug release from an implanted device, the consequences for an implanted glucose sensor can lead to dire situations. In particular, an inaccurate glucose measurement could lead a person to dose with insulin when it is not necessary; therefore, implanted glucose sensors must be highly accurate so that persons with diabetes can have the necessary confidence to make a clinical decision such as dosing with insulin.

The concept for diabetes management via an implanted glucose sensor is in its fifth decade (Clark and Lyons, 1962), and original papers describing oxidase-based glucose sensors are more than 45 years old. While a significant effort has been expended to make different types of glucose sensors using various forms of transducers, complications caused by the FBR have plagued the success of glucose sensors for persons with diabetes becoming a universal reality. Although different processes can degrade an implanted sensing device in vivo (Wisniewski et al., 2000a), the FBR has been the most critical factor necessary to overcome.

One of the major challenges for achieving long-term, reliable glucose sensors for diabetes management has been to overcome the FBR and its effects on sensor output and function (Brauker, 2009; Cunningham and Stenken, 2010; Fraser, 1997; Ward, 2008). Fibrous capsule formation reduces solute supply and capillary density and recruits macrophages, thus leading to performance variation and/or cessation of the implanted device (Mou et al., 2011; Novak et al., 2010; Wisniewski et al., 2000b). The fibrotic capsule often leads to the failure of many medical devices, such as glucose sensors, because chemical communications and the transport of analytes are restricted (Dang et al., 2011; Gough and Armour, 1995; Reach and Wilson, 1992; Rebrin et al., 1992). The dynamic continuum of the FBR also affects localized glucose concentrations surrounding an implanted sensor, which can lead to erratic signal during the various stages of the FBR. To reduce the extensive fibrosis that impairs the long-term use of implanted glucose sensors, there is much interest in redirecting the immune response toward an antifibrotic response (Jones, 2008).

3.3 Strategies to overcome the FBR

The main strategies to overcome the FBR with glucose sensors include incorporating an active drug release strategy into the sensor materials to affect different aspects of the FBR, i.e., tissue inflammation and angiogenesis promotion. The most common agent used for this purpose is dexamethasone, while other chemical agents such as nitric oxide and VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) have also been employed. Materials-based approaches have focused on texturing or the use of porous materials surrounding the glucose sensor.

Dexamethasone, a glucocorticoid, is a highly potent anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressant drug. Dexamethasone and other glucocorticoids depress the immune response by decreasing cytokine and prostaglandin release, resulting in fewer inflammatory cells at the drug site. Furthermore, this drug reduces capillary permeability and suppresses fibroblast proliferation. Moreover, dexamethasone inhibits angiogenesis via inhibition of VEGF. Given dexamethasone’s powerful biological effects, the incorporation of the drug into materials that allow its localized active release is better than systemic delivery. Dexamethasone release and its use in combination with an implanted sensor have been reported by several different groups (Bhardwaj et al., 2010; Croce et al., 2013; Hickey et al., 2002; Klueh et al., 2007; Morais et al., 2010; Patil et al., 2004; Ward et al., 2010b)

Fibrosis and encapsulation are events within the FBR that prevent an adequate blood supply to the implant site. For glucose sensors, this process is believed to cause a significant mass transport lag and potential utilization of glucose before it can reach the sensor implant site. VEGF has been used in combination with glucose sensors using direct injection (Ward et al., 2003), osmotic pumps (Ward et al., 2004), controlled release (Norton et al., 2007; Patil et al., 2007), and gene transfer (Klueh et al., 2004). In two of these studies, both dexamethasone and VEGF were co-released from materials surrounding a sensor (Norton et al., 2007; Patil et al., 2007). In each of these cases, a significant increase in vessel density surrounding the implanted sensor was observed.

More recently, nitric oxide (NO) has been proposed as an active release agent for improving the reactions of the FBR (Shin and Schoenfisch, 2006). For implanted glucose sensors, a significant reduction in inflammation and run-in times have been reported (Gifford et al., 2005). This work is continuing with improvements to the delivery technology being reported (Hetrick et al., 2007; Nichols et al., 2011).

These different chemical agents (dexamethasone, VEGF, and NO) have been used for a significant amount of time with little understanding of how the localized tissue biochemistry is influenced by the release of these agents. The ability to shift the direction of the FBR response will require understanding the FBR origins and the temporal resolution of key signaling molecules. Microdialysis sampling has a unique role to play with respect to monitoring the localized biochemistry while also locally delivering prophylactic agents to influence the tissue space surrounding the microdialysis probe.

4.0 Macrophage Polarization and Biomaterials

Macrophages exist in a continuum of phenotypic populations. It is this plasticity that makes them particularly pertinent when studying the FBR. The plasticity of macrophages and their polarization states comprise a rapidly expanding research area (Mantovani et al., 2004a; Martinez et al., 2009; Mosser and Edwards, 2008). Macrophages are currently classified as M1 (i.e. “classical”) and M2 (i.e. “alternatively”) activation states, although it is well-recognized that macrophage states comprise a continuum (Mosser and Edwards, 2008). The M2 state is further divided into classifications designated as M2a, M2b, and M2c sub-phenotypes. While M1 macrophages are aggressive in their pursuit to digest foreign objects and therefore prompt an inflammatory response, M2 macrophages, specifically the M2c phenotype, are thought to induce an anti-inflammatory, pro-healing, pro-tissue remodeling response.

Specific cytokines have been identified as moderating agents that direct macrophage polarization, and their production is used to characterize the presence of particular macrophage states. For example, M1 macrophages are induced by interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor-necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), characterized by high levels of interleukin-12 (IL-12) and interleukin-23 (IL-23) and low levels of IL-10, and produce inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6, whereas M2 macrophages are induced by IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 and are characterized by high levels of these cytokines and low levels of IL-12 and IL-23 (Brown et al., 2012; Mantovani et al., 2005; Schmidt and Kao, 2007; Sica and Mantovani, 2012). The induction of M2 sub-phenotypes is of particular interest to modulating the FBR, especially the M2c phenotype. This phenotype is thought to be induced by IL-10 and (Tissue Growth Factor-β) TGF-β and to express Interleukin-4 Receptor α (IL-4Rα) (Martinez et al., 2008; Villalta et al., 2011). Many reviews have comprehensively summarized and extensively described this orchestration of macrophages and cytokines during the FBR and macrophage polarization (Ao and Stenken, 2006; Brancato and Albina, 2011; Broughton et al., 2006; Kou and Babensee, 2011; Mantovani et al., 2004b; Martinez et al., 2008; Mosser and Edwards, 2008; Rodero and Khosrotehrani, 2010). Despite this extensive research focus, incorporating macrophage polarization steps to an implanted biomaterial is an active research area.

Directing macrophages at the biomaterial/tissue interface to a phenotype that promotes wound healing and tissue integration while reducing excessive inflammation or fibrosis is considered a pivotal advance for biomaterials (Brown et al., 2012). If macrophage polarization can be achieved in vivo at the biomaterials/tissue interface, then it would serve as a likely remedy to overcoming the detrimental effects of the FBR and would increase the longevity of the implant.

5.0 Microdialysis Sampling in studying FBR and Macrophage Polarization

The literature suggests that eicosanoids, cytokines, and MMPs are the most important extracellular chemical modulators orchestrating the foreign body response. In vivo, these bioactive agents work in concert, and the cellular combination that secretes them cannot be replicated in an in vitro setting. The different bioactive agent combinations and concentrations direct and modulate the cellular traffic to the biomaterial implant site. There is a variety of "stop" and "go" signals within the entire extracellular matrix that serve as checks and balances for dictating the FBR outcome.

Many recent reviews in the wound healing and surgical research literature indicate that cytokines and growth factors are implicated in controlling the outcome of a wound (Eming et al., 2009; Werner and Grose, 2003) and are important for biomaterials research. However, these recent reviews clearly point out the inadequate knowledge of the specific cytokines and growth factors involved during the various phases of in vivo wound healing. Direct and real-time measurements at the material implant site are an important step toward determining the generated molecular signals. Combining this molecular information with emerging knowledge of the immunological aspects of biomaterials interaction in host tissue will facilitate translational approaches that may involve integrating different cytokines, drugs, growth factors, or other agents (e.g., viruses or stem cells) into the biomaterial. Microdialysis sampling is suitable for these types of studies since the probe can be used to collect solutes from the extracellular fluid (ECF) as well as locally deliver different solutes. The FBR also has different stages through which different cell populations migrate in and out of the implant space. Analysis of the dialysates provides temporal snapshots that indicate the chemical signaling events occurring during the FBR. Alterations in these chemical signaling events may be indicative of the conditions necessary to modulate the FBR, thereby maintaining device functionality and increase implant longevity.

Membranes incorporated into microdialysis sampling devices have different materials chemistry when compared to polymers used for glucose sensors. However, the sizes of these devices are nearly equivalent in terms of their length and external diameter. Because microdialysis sampling is diffusion-based, various chemicals can be added to the perfusion fluid and delivered to the ECF to influence localized tissue biochemistry while collecting solutes from the ECF.

In an effort to direct and study the immune response, our laboratory surgically implants microdialysis probes into the dorsal, subcutaneous space of rats, allowing simultaneous delivery of agents that redirect the immune response and the collection of dialysate samples that are analyzed for cytokines and other cell-signaling proteins. The changes in concentration of these proteins, supplemented with immunohistochemistry (IHC) and histological analysis, are good indications of the macrophages present and active. By infusing different agents, including cytokines, through the microdialysis probe, we hypothesize that in vivo direction of macrophage polarization states can be altered. Polarizing macrophages to their M2c state would alter the immune response responsible for tissue remodeling and thereby diminish the fibrotic response.

5.1 Protein Adsorption onto Microdialysis Membranes

For individuals not experienced with the use of microdialysis sampling, a common belief is that solute collection through implanted microdialysis probes will be significantly hindered due to protein adsorption onto the dialysis probe. Microdialysis membranes are cut from kidney dialysis membranes for which there are proteomics-based approaches reported for quantifying protein adsorption to hemodialysis membranes (Cornelius and Brash, 1993). Even with large kidney dialyzer units with > 100 cm2 of surface area, the total amount of protein that is often desorbed from the polymer is less than 50 µg/mL (Bonomini et al., 2006; Urbani et al., 2012). More recently, a proteomics investigation to determine the adsorbed proteins for microdialysis membranes used in a microdialysis context has been described (Dahlin et al., 2012; Dahlin et al., 2010). These different studies show what has been described in the literature: proteins exhibit differential adsorption that is related to the surface chemical properties of the membrane (or material) (Norde et al., 2012), the physicochemical properties of the protein, and the surface roughness of the polymer.

Despite the perpetuation of the “myth” that protein fouling reduces the effectiveness of microdialysis sampling, the technique has been used in nearly every single tissue and fluid in mammalian systems, as well as in complex in vitro systems such as effluent from pulp and paper production (Torto et al., 1999). While the membranes used for microdialysis sampling do appear to adsorb different materials, this adsorption does not appear to preclude its use for sampling of small, low molecular weight molecules.

For protein collection, the potential for non-specific adsorption and the potential loss of analyte due to such adsorption processes are real concerns and have been shown to occur with cytokine proteins. Not including a blocking protein, such as albumin, in the perfusion fluid significantly reduces the ability to collect different cytokine proteins that are often present in low pg/mL concentrations (Trickler and Miller, 2003).

5.2 Collection of Leukotrienes/Prostaglandins

Leukotrienes and prostaglandins (eicosanoids) are metabolic products of the arachidonic acid pathway and have been widely implicated in different disease states (Peters-Golden et al., 2005). These important signaling molecules are perhaps not as well studied as cytokines due to hydrophobicity, ng to pg levels of bioactivity, and half-lives of seconds to mere minutes in biological systems (Folco and Murphy, 2006; Maddipati and Zhou, 2011). The metabolites of the arachonidic acid pathway are quite extensive, and there are only a few immunoassays available for select targets within this pathway (Kumlin, 1996). For decades, gas chromatography with mass spectrometry was used for quantifying these analytes with appropriate derivitization schemes (Maskrey and O'Donnell, 2008; Tsikas, 1998). More recently, liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC/MS) methods have been described (Ecker, 2012; Masoodi et al., 2010; Murphy et al., 2005).

The use of microdialysis sampling for the collection of the bioactive arachidonic acid metabolites has not been as extensive as for other analyte classes (Callaghan et al., 1994; Church et al., 2002; Hedenberg-Magnusson et al., 2001, 2002). While there are a few reports describing the use of microdialysis sampling for collecting different eicosanoids, a problem that frequently arises is the lack of quantitation of particular analytes that are expected. Usually this is because their concentrations are too low. This may be due to many factors including the fractional recovery, hydrophobic interactions, or non-specific adsorption of the low concentration lipids with the microdialysis membrane. These non-specific adsorption interactions have been addressed by inclusion of binding agents such as cyclodextrins (Kjellstrom et al., 1998; Sun and Stenken, 2003). However, depending on the type of analysis being used, cyclodextrins may interfere or not allow necessary binding as with antibody-based assays.

5.3 Collection of Reactive Oxygen Species

Microdialysis sampling has been used for the collection of reactive oxygen species and related metabolic products of oxidative stress. Oxidative stress is a term used to encompass the myriad of products that can be produced when oxygen metabolism gets out of balance. This includes oxidation of proteins, lipids, and even nucleic acids. This work is highly challenging as artifacts can arise (Cadet et al., 2011; Collins et al., 2004). Additionally, artifacts for radical trapping procedures using benzoic acid derivatives, as well as standard trapping agents such as 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO), have been described for microdialysis sampling (Dugan et al., 1995; Ste-Marie et al., 1996).

Given the concerns regarding radical trapping with agents such as hydroxybenzoic acids, which can undergo metabolism or other oxidative chemical transitions, the use of spin trapping agents that can be confirmed for appropriate radical trapped identity has promise in microdialysis sampling (Chen et al., 2004). Using appropriate hardware technology to significantly reduce the volume necessary, dialysates can be monitored for trapped agents using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) techniques.

5.4 Collection of Cytokines

Microdialysis sampling was originally conceived to allow collection of low molecular weight solutes. For decades, the mantra was that microdialysis sampling provides protein-free samples allowing for direct quantitation of the collected dialysate. As it was discovered that more than just low molecular weight solutes signal through the extracellular fluid space, the microdialysis technique was then applied to larger molecular weight solutes (Clough, 2005). Thus, it is actually somewhat ironic that microdialysis sampling approaches are used to collect soluble bioactive signaling proteins from the ECF. Collection of these proteins poses many challenges and technical modifications that are necessary to be successful.

5.4.1 Membrane and Perfusion Fluid Needs

While there are many different bioactive proteins, cytokines comprise the largest class with biomedical interest. Cytokines have molecular weight ranges between approximately 6 to 80 kDa. Microdialysis sampling membranes come in many different molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) ranges, including 5 to 6 kDa for cuprophan and up to 100 kDa for some types of polyethersulfone (PES) membranes. The membrane MWCO is defined using kidney dialysis parameters rather than what the membrane can achieve as a MWCO with it incorporated into a microdialysis sampling device. The actual recovered molecular weights through dialysis membranes have been described and show that extraction efficiency is significantly compromised and reduced as the solute molecular weight begins to approach approximately 25% or greater of the membrane MWCO (Schutte et al., 2004; Snyder et al., 2001). This causes significant challenges with cytokines since many can be in the range of the MWCO. For these reasons, some researchers have chosen to use large MWCO of the plasmapheresis type in the 3,000 kDa MWCO range (Clough et al., 2007; Winter et al., 2002).

A significant technical challenge when using larger MWCO membranes with greater than 50 kDa MWCO is that many of these membrane materials are used purposely to achieve ultrafiltration. A new trend in hemodialysis is to move toward larger pore membranes to achieve higher water flux (Boure and Vanholder, 2004). For microdialysis sampling, this exacerbates the known ultrafiltration problem that commonly occurs with larger MWCO and thus larger pore membranes. To overcome ultrafiltration problems, which cause significant fluid to be lost across the microdialysis membrane thus making it appear to “sweat” if one is performing an in vitro experiment, the use of different osmotic balancing agents such as dextrans are commonly employed. These agents were originally proposed for use when higher molecular weight cutoff polyethersulfone (PES) membranes were incorporated to collect larger proteins from skeletal muscle (Rosdahl et al., 1997).

It is now common to include high molecular weight dextrans into the perfusion fluid as a means to balance the pressure differential. However, we have recently shown that inclusion of the dextran in the perfusion fluid, specifically Dextran-70, which has been demonstrated to be lost across the 100 kDa MWCO membrane (Schutte et al., 2004), causes significant inflammation [Keeler, submitted to this journal]. It is recommended that Dextran-500 be used as an alternative to Dextran-70 since it does not easily diffuse through the membrane pores.

The hollow fiber membranes used for microdialysis sampling are the same membranes typically used for kidney dialyzer units. The difference between the low and high MWCO membranes is pore size and water flux. A significant issue among nephrologists is the removal of different bioactive proteins that are not wanted in blood in high concentrations. In particular, it is interesting to note that in the hemodialysis community, there is a significant interest in removing cytokines either by filtration through a hollow fiber membrane with minimal loss onto the membrane material or by actual adsorption of the cytokines onto the membrane materials. Cytokine adsorption onto various hemodialysis membranes has been described in the literature (Atan et al., 2012; Bouman et al., 1998; Hirayama et al., 2011; Matsuda et al., 2001). The use of appropriate blocking agents such as albumin appears to greatly reduce the loss of cytokines to microdialysis membranes (Trickler and Miller, 2003). However, there does appear to be differential binding preferences since we have found differences in recovery of the cytokine CCL2 (Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1, MCP-1) when fetal bovine serum was used instead of albumin in the perfusion fluid (Wang and Stenken, 2009b) as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Control and Enhanced RRs of human MCP-1 in different measurement systems (Luminex and ELISA) by using 0.1 µM heparin.

| Luminex DATA(n=3) | ELISA DATA(n=3) | |

|---|---|---|

| Control RR | ||

| 9.0±1.6% | 19.9±0.8%* | |

| 0.5 µL/min Enhanced RR |

||

| 19.5±2.7% | 39.9±0.3%* | |

| 0.5 µL/min Control RR |

||

| 6.0±2.5% | 10.5±0.6% | |

| 1.0 µL/min Enhanced RR |

||

| 13.1±3.0% | 18.0±0.4% | |

| 1.0 µL/min |

The Luminex and ELISA data are statistically different at the p < 0.05 level using a Student’s t-test. The Luminex assay buffers contain bovine serum albumin (BSA). The ELISA contains fetal bovine serum (FBS).

Reprinted from: Affinity-based microdialysis sampling using heparin for in vitro collection of human cytokines, Anal Chim Acta. 651(1):105–11, 2009 with permission from Elsevier

5.4.2 Cytokine Collection, Measurement, and Validation

Cytokines are a collective group of proteins that act within the immune system. There are more than 100 identified cytokines; however, new cytokines continue to be discovered. As a group, these proteins are quite different with respect to their physicochemical properties in solution and their biological activity. For example, many of the chemokines (chemoattractant cytokines) are known to bind to tissue glycosaminoglycans (Shute, 2012). This complicates the collection of such proteins via microdialysis sampling due to their binding to the tissue components.

Microdialysis sampling has been used for successful collection of cytokines from many different tissues and species (Ao and Stenken, 2006). Human microdialysis sampling of cytokines is far more advanced in terms of scope than rodent due to the use of longer membrane lengths and lower perfusion fluid flow rates, which lead to higher recovery of cytokines as compared to smaller animal probes used at higher flow rates. Additionally, the importance of elucidating cytokine networks in clinical medicine is a contributing factor to the advancement of using microdialysis sampling for these proteins.

Our research interest in cytokine sampling came from the perspective of elucidating the foreign body reaction to implanted microdialysis probes used as glucose sensor mimics. Based on previous work that we had performed using cyclodextrins as trapping agents in the dialysis perfusion fluid, we aimed to improve cytokine collection through microdialysis probes by including antibody-immobilized beads in the perfusion fluid (Ao et al., 2004). We next demonstrated that cytokines could be collected in vivo by placing probes into the peritoneal cavity of mice dosed with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a bacterial endotoxin that causes cytokines to be released from macrophages (Ao et al., 2005; Sweet and Hume, 1996).

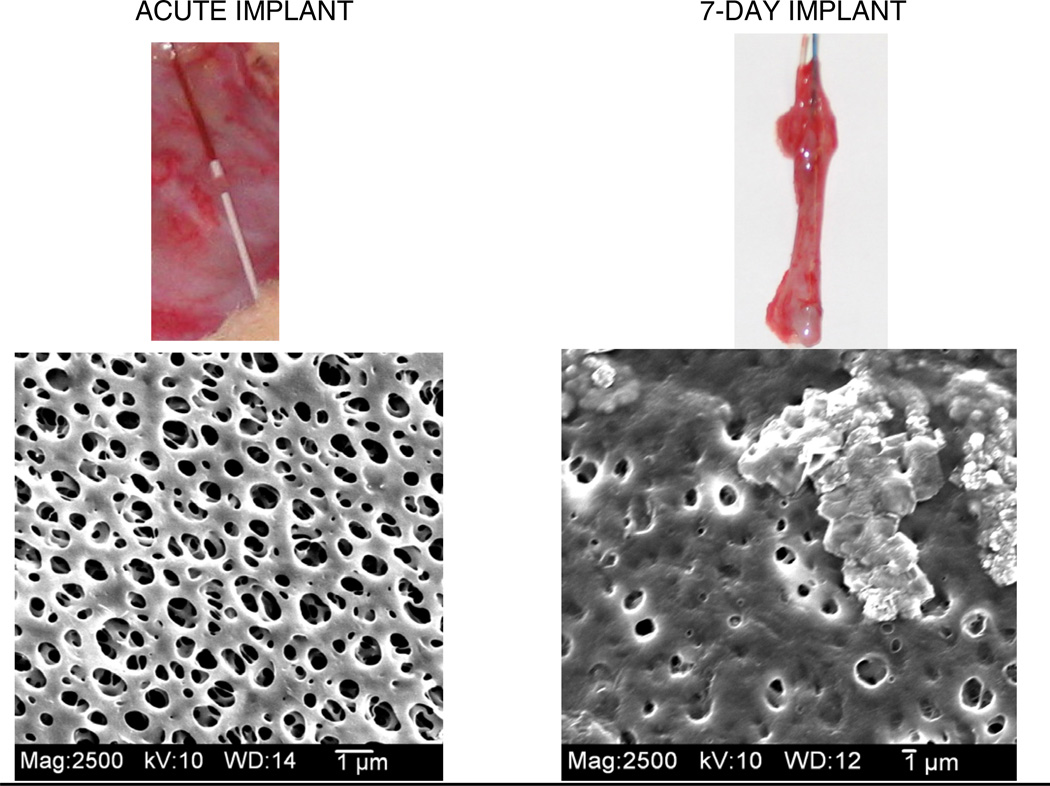

To elucidate cytokine responses surrounding an implanted material, it was first necessary to determine if cytokines could be collected. This was followed by evaluation of the effects of the long-term implant and subsequent FBR on cytokine concentrations in the dialysates or possible prevention of cytokine mass transport to the probe (Wang et al., 2007). To perform this study, microdialysis probes were implanted acutely for 3 and 7 days into the subcutaneous space of male Sprague-Dawley rats. Cytokines were elicited using an LPS injection, and interleukin-6 (IL-6) was quantified from dialysates using an ELISA. IL-6 concentrations measured from the acute implant (Day 0) were more than eight-fold higher than the concentrations measured for Days 3 and 7, thus indicating changes in tissue properties surrounding the implanted probe. Probes and surrounding tissue were explanted on Day 7, where an apparent fibrotic encapsulation of the probes was observed. The reduction in ability to collect IL-6 on Days 3 and 7 (compared to Day 0) were likely due to the granulation tissue formation and angiogenesis of the wound healing process (Day 3) followed by later stages of the FBR (Day 7), including fibrotic encapsulation (Figure 3). Thus, with respect to IL-6 generated from a tissue site away from the implanted dialysis probe, the transport of IL-6 to the implanted microdialysis probe was significantly hindered. This could pose potential problems for other situations with long-term implanted microdialysis probes.

Figure 3.

Example of explanted probes and the SEM images of the membrane for an acute implant (left) and 5-day) implanted microdialysis probes in Sprague-Dawley rats.

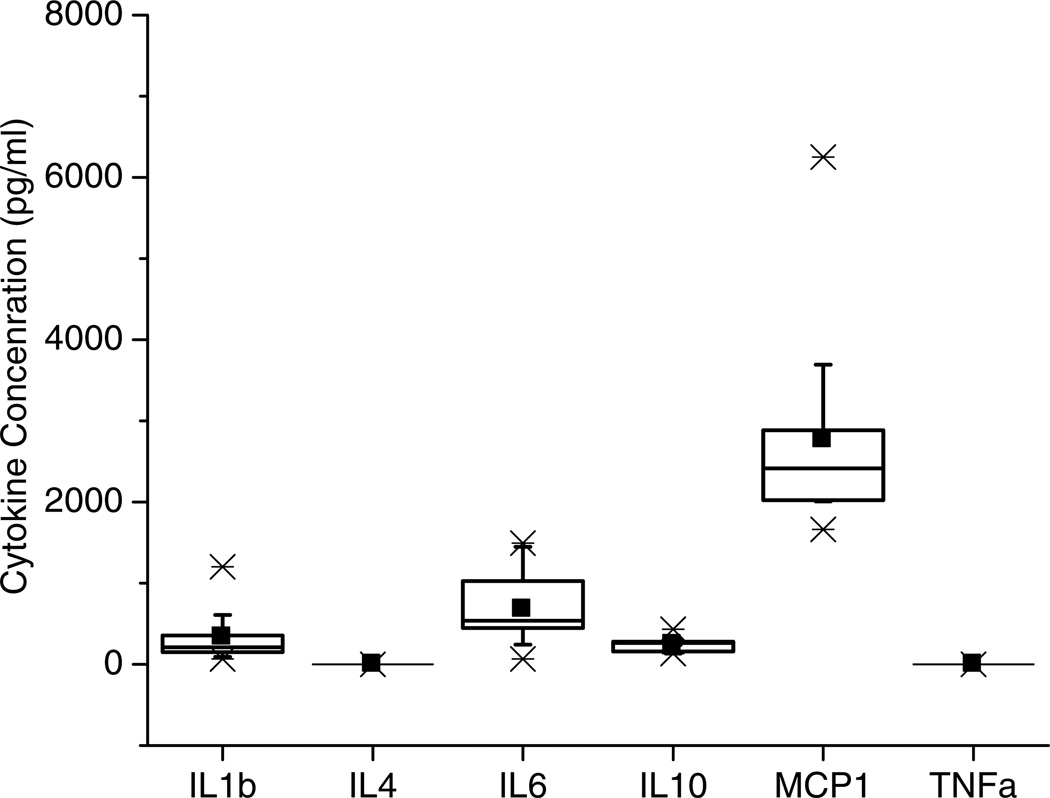

An interesting finding in this work was the ability to collect basal levels of IL-6 that were collected from the implanted dialysis probes prior to LPS treatment. These low pg/mL basal levels (300–500 pg/mL) of IL-6 suggested a low level of inflammation surrounding the microdialysis probe as a result of the implantation. This work also suggested the possibility for longer-term collection of cytokines during the FBR. However, prior to implanting microdialysis probes and collecting cytokines, it was necessary to determine the approximate cytokine concentrations that would be expected during different stages of the FBR. For this reason, we implanted plastic tubes that allowed for the collection of extracellular fluid when explanted (Wang et al., 2008). In this study, the differences in concentrations among the targeted cytokines (CCL2 (MCP-1), IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α) were of particular interest. Among these cytokines, only IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, and CCL2 (MCP-1) were quantified (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cytokine levels represented as box plots after implanting a hollow polymer tube into rat subcutaneous tissue. Reprinted from Multiplexed cytokine detection of interstitial fluid collected from polymeric hollow tube implants—A feasibility study, Cytokine43(1):15–19, 2008 with permission from Elsevier.

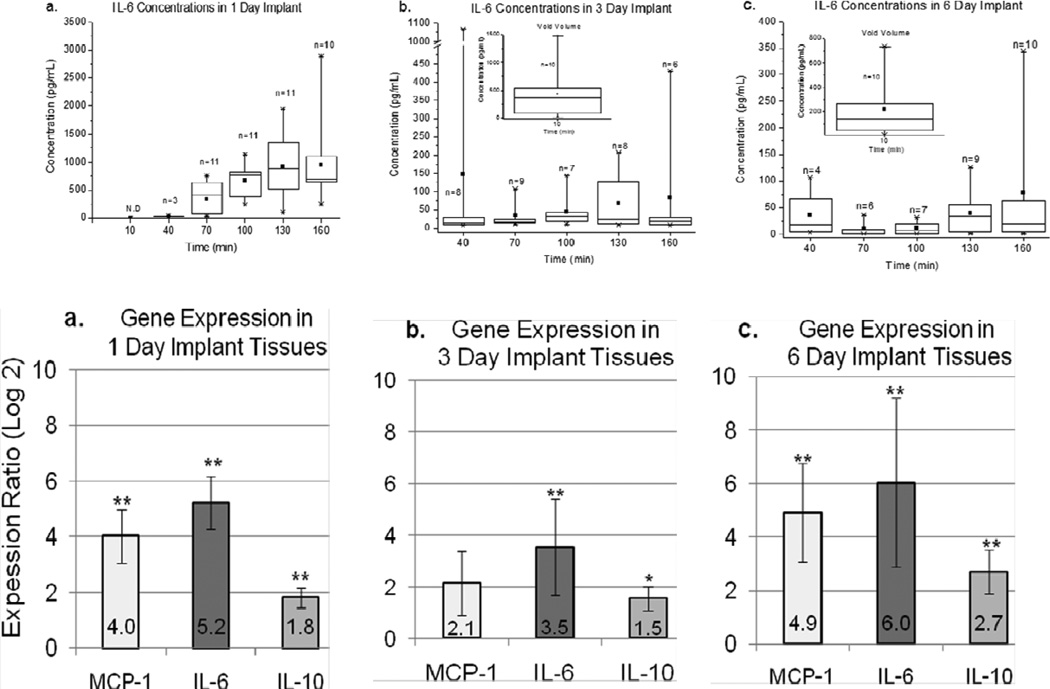

Long-term in vivo sampling of cytokines collected by implanted microdialysis probes is particularly important when considering the impacts of the FBR. In a study by von Grote et al. (von Grote et al., 2011), results of cytokine measurements using a fluorescence bead-based immunoassay and qRT-PCR were compared. Immunoassays were used to quantify CCL2, IL-6, and IL-10 in dialysates collected on Day 1, 3, and 6 post-implantation of the microdialysis probe into the subcutaneous space of male Sprague-Dawley rats, and tissue harvested on corresponding days was used to determine the gene expression for the cytokines, as well as histological (H & E and Masson’s Trichrome) analysis. Cytokine concentrations and gene expression activity for all measured cytokines increased throughout the course of Day 1, followed by a decrease on Day 3 and a rebound on Day 6. The rebound in cytokine levels for IL-6 and CCL2 on Day 6 may have indicated the cytokine profile of a gradual transition from wound healing to later stages of the FBR (Figure 5). This was also observed from histological evaluation as well as the qRT-PCR data. Immune cell recruitment and collagen accumulation surrounding the microdialysis probes explanted on Days 1, 3, and 6 were thought to be consistent with the temporal progression of cellular activity leading to later stages of the FBR. Spatial and cellular events that promote the FBR were observed for Days 1 and 6, although the dense aggregation near the microdialysis probe/tissue interface was significantly greater on Day 6 than that for Day 1.

Figure 5.

Comparison of IL-6 concentrations collected in dialysates (top) versus qRT-PCR data (bottom) from tissue surrounding a microdialysis sampling probe after different implantation days. Adapted from: von Grote, et al. (2011) Mol Biosyst 7, 150–161 with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry.

5.5 Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs)

During the FBR to implanted biomaterials, adherent macrophages secrete matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), proteolytic enzymes involved in the degradation of the extracellular maxtrix (ECM) and collagen turnover throughout the wound healing process. Additionally, tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMPs) are also secreted by macrophages. The concomitant release of MMPs and TIMPs juxtaposes the opposing, yet necessarily concurrent, FBR processes of ECM remodeling and fibrosis in response to the implantation of a biomaterial. The role of MMPs in the FBR is not limited to ECM hydrolysis. MMPs are also responsible for triggering cytokine release from the ECM. Upon ECM degredation, inactive, or “pro-“, forms become active. TGF-β, for example, and members of the tumor necrosis family and their receptors are proteolytically activated by MMP-9, thereby increasing angiogenesis at the implant site (Yu and Stamenkovic, 2000). MMP-1, -2, -3, -8, -9, -12, -13, and -18, as well as TIMP-1 and -2, have all been investigated for their roles in the FBR, particularly the involvement of MMP-1, -2, -8, -9, and -13 in the reversal of fibrosis (Jones et al., 2008; Wynn and Barron, 2010). MMP-2 and MMP-9 are of specific interest due to their duality of facilitating either pro- or anti-inflammatory responses (Junge et al., 2012). This duality, however, may be needed to mediate, if not reverse, fibrosis. Analysis of MMP/TIMP concentrations and ratios in response to biomaterials and pharmacological inhibition has shown that despite being secreted from macrophages, MMPs are also factors in macrophage adhesion and fusion into foreign body giant cells, processes which are, in turn, responsible for subsequent secretion of MMPs and TIMPs (Jones et al., 2008). Understanding the mechanisms of continuous inflammation and ECM degradation by MMPs activated by macrophages is, therefore, crucial for gaining insight into modulation of fibrotic encapsulation and increasing the longevity of implanted biomaterials.

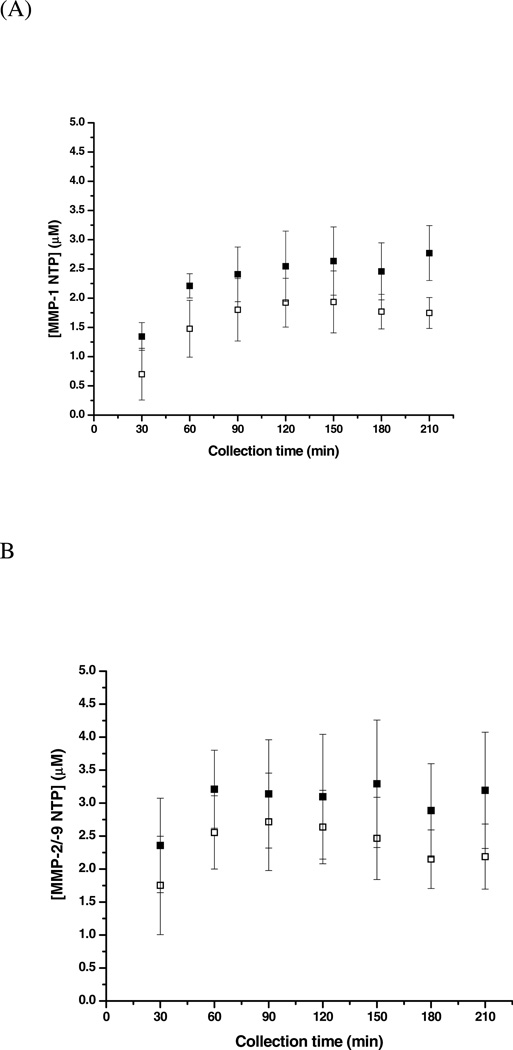

In addition to developing bioanalytical chemistry methods to collect and quantify cytokines and direct and analyze macrophage polarization, our laboratory has also generated a method to determine the localized proteolytic activity of MMPs near the microdialysis probe site shown in Figure 6 (Wang et al., 2009). In this study, MMP-1 and MMP-9 (with and without the addition of a broad spectrum MMP inhibitor) were infused subcutaneously. Lower molecular weight cutoff membranes (20 kDa) were selected for the MMP studies as compared to those used for macrophage and cytokine studies (100 kDa), thus preventing the diffusion of MMPs into the perfusion fluid and the continued cleavage of substrates in the dialysates post collection. An LC/MS/MS method was developed to quantify product formation in the collected dialysates. The MMP-1 N-terminal product (NTP) and MMP-2/MMP-9 NTP were quantified for dialysates collected on Day 0, Day 3, and Day 7 post-implantation of the microdialysis probe and substrate infusion. Results from the substrate infused experiment showed that the concentrations of MMP-1 NTP and MMP-2/-9 NTP decreased from Day 0 to Day 3 to Day 7. The temporal decrease in the concentrations of the products was not a dramatic for the experiment where the inhibitor was infused with the substrate; however, there was an overall decrease in product formation (28–31% for MMP-1 NTP and 22–28% for MMP-2/-9 NTP) when inhibitor was added versus when only substrate was infused. Analysis of this data suggests that quantifying enzymatic product formation via microdialysis sampling combined with LC/MS/MS detection provides valuable information about in vivo changes in MMP enzymatic activity and reactions outside the microdialysis probe. Additionally, tissue surrounding the implanted microdialysis probes was harvested and analyzed using zymography to confirm the presence of MMPs around the microdialysis probe. The detection of MMPs in tissue encapsulating the foreign body microdialysis probe and temporal quantification of MMP cleavage products in corresponding microdialysis samples can be used to gain information about the FBR process, specifically the fibrotic encapsulation of a sampling device or sensor, and to modulate the fibrotic response in an effort to increase device longevity.

Figure 6.

MMP-1 NTP and MMP-2/-9 NTP formation in the control dialysate versus inhibition dialysate on day 0 of implantation. Reprinted with permission from Analytical Chemistry 81(24):9961–9971. Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society.

5.6 Modulator or Drug Infusion to Alter the FBR

A microdialysis sampling probe has the potential to be used as a localized drug delivery device as well as a collection device. Using the microdialysis probe as a localized delivery device is significant since bioactive chemicals can be readily included in the perfusion fluid. This essentially allows the microdialysis probe to be a drug delivery device with rapid turnaround with respect to identifying modulators or prophylactic agents that will serve to be antifibrotic. In particular, judiciously selecting agents that direct macrophages to an M2, specifically an M2c, polarization state will significantly improve solving the fibrosis issue that has long been an intractable problem within biomaterials science. During a microdialysis experiment aimed to elucidate tissue biochemistry, control dialysates can be collected on an animal before infusing a drug, or multiple microdialysis probes can be implanted into the same animal. In the case of subcutaneous work, two microdialysis probes can be implanted in the same animal, one serving as the control and the other used to deliver bioactive chemicals. If bioactive agents are not desired to pass through the probe, other compounds that serve to monitor different aspects of the tissue biochemistry, such as 2-deoxyglucose, can be included in the perfusion fluid (Mou et al., 2010).

In a study by Mou et al., our laboratory presented modulation of the FBR by using microdialysis sampling as a dual drug delivery/sample collection technique (Mou et al., 2011). A treatment of CCL2 or dexamethasone 21-phosphate (dex-phos) was infused with internal standards (2-deoxyglucose, antipyrine, and vitamin B12) to assess the FBR (via histological Masson’s Trichrome staining) and the effect of the induced FBR on the extraction efficiencies of the implanted microdialysis probes. Control and treatment probes were implanted on each male Sprague-Dawley rat, where treatments were infused on the day of implantation and samples were collected. Sampling continued through Days 7 and 12 post-implantation (control and treatment) and Days 10 and 14 post-implantation (control and treatment) for CCL2 and dex-phos infusion experiments, respectively. Since CCL2 activates the immune response and directs monocytes to the foreign body, the resulting large fibrotic encapsulation of the explanted microdialysis probe and surrounding tissue (twice the thickness as the corresponding control probe) was anticipated and was the reason for probes failing two days before corresponding control probes. Histological analysis of explanted probes and surrounding tissue showed an extensive cellular layer at the tissue/microdialysis probe interface with a rich collagen layer embedded with blood vessels for CCL2 microdialysis probes compared to an adjacent cell layer, thin collagen layer, and outer layer of blood vessels for the corresponding control probe. Dexphos is converted to dexamethasone by esterases in vivo, which is used as an anti-inflammatory agent to reduce the FBR (Derendorf et al., 1986; Morais et al., 2010; Ward et al., 2010a). Therefore, it was also not surprising that more fragile capsules surrounded explanted microdialysis probes and surrounding tissue for the dex-phos infusion as compared to the corresponding control; the dex-phos and control tissue thickness was similar, but the capsules surrounding the dex-phos microdialysis probes appeared to be less fibrotic. In fact, it was reported that the dex-phos treated tissue was more difficult to section due to fragility, resulting in poor histological images. Analysis of dialysates by HPLC-ESI/MS/MS allowed for quantification of dexamethasone and internal standards. Results indicated that dex-phos was converted to dexamethasone in the experiment. Internal standards were chosen to determine if localized metabolism (2-deoxyglucose), localized blood flow (antipyrine and vitamin B12), and/or membrane biofouling affected the microdialysis probe calibration. Only minor differences in the internal standard concentrations were observed between control, CCL2, and des-phos treatments, thus indicating that while the calibration of the probe was not consistently affected by the fibrotic encapsulation, the FBR did dramatically affect the longevity of the implanted device.

6.0 Summary and Conclusions

In this review, we have highlighted our recent studies using the rat model to investigate the use of microdialysis sampling to modulate the FBR. Using the dual delivery/sample collection microdialysis technique, our laboratory has employed various strategies to advance the delivery and recovery of cytokines and other signaling molecules to better evaluate the FBR (Ao et al., 2004; Ao and Stenken, 2006; Duo and Stenken, 2011a; Duo and Stenken, 2011b; Mou et al., 2010; Wang and Stenken, 2009a). Modulation of the FBR is not only significant in biomaterials science, but moderating the effects of the FBR specifically upon implantation of a microdialysis sampling device will also be crucial to furthering drug development for a variety of fields in pharmaceutical and clinical research. Elucidation of how fibrosis can be mediated and how the signaling events and inflammatory cells are modulated is necessary to be able to translate this basic research into the clinic.

In addition to the dialysate samples, it is also important to include appropriate end-point histological, immunohistochemical (IHC), and gene expression analysis via quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Quantitative results from the tissue samples integrated with the implanted microdialysis probe can then be correlated to the results for the corresponding time-resolved dialysates.

Finally, a significant technical challenge that remains is the unavailability of robust microdialysis probes that can survive in an animal. In the past, we have been able to collect for 10 to 14 days; however, current microdialysis probes (CMA-20s) are only reliable for about 5 to 7 days in rats. The FBR is a process that can occur over a period of a month; therefore, more robust devices are necessary to allow for molecular signaling measurements from the wound site for more than a week.

Acknowledgement

Microdialysis sampling studies of the FBR have been supported by the NIH (EB 001441, EB 014404).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson JM, Miller KM. Biomaterial biocompatibility and the macrophage. Biomaterials. 1984;5:5–10. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(84)90060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JM, Rodriguez A, Chang DT. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Semin. Immunol. 2008;20:86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ao X, Rotundo RF, Loegering DJ, Stenken JA. In vivo microdialysis sampling of cytokines produced in mice given bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J Microbiol Methods. 2005;62:327–336. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ao X, Sellati TJ, Stenken JA. Enhanced microdialysis relative recovery of inflammatory cytokines using antibody-coated microspheres analyzed by flow cytometry. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:3777–3784. doi: 10.1021/ac035536s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ao X, Stenken JA. Microdialysis sampling of cytokines. Methods. 2006;38:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atan R, Crosbie D, Bellomo R. Techniques of Extracorporeal Cytokine Removal: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Blood Purif. 2012;33:88–100. doi: 10.1159/000333845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austen KF. The cysteinyl leukotrienes: Where do they come from? What are they? Where are they going? Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:113–115. doi: 10.1038/ni0208-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellis SL. Advantages of RGD peptides for directing cell association with biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2011;32:4205–4210. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste H, Drejer J, Schousboe A, Diemer NH. Regional cerebral glucose phosphorylation and blood flow after insertion of a microdialysis fiber through the dorsal hippocampus in the rat. J. Neurochem. 1987;49:729–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj U, Sura R, Papadimitrakopoulos F, Burgess DJ. PLGA/PVA hydrogel composites for long-term inflammation control following s.c.implantation. Int. J. Pharm. 2010;384:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomini M, Pavone B, Sirolli V, Del BF, Di CM, Del BP, Amoroso L, Di IC, Sacchetta P, Federici G, Urbani A. Proteomics Characterization of Protein Adsorption onto Hemodialysis Membranes. J. Proteome Res. 2006;5:2666–2674. doi: 10.1021/pr060150u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouman CSC, Van ORW, Stoutenbeek C. Cytokine filtration and adsorption during pre- and postdilution hemofiltration in four different membranes. Blood Purif. 1998;16:261–268. doi: 10.1159/000014343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boure T, Vanholder R. Which dialyzer membrane to choose? Nephrol., Dial., Transplant. 2004;19:293–296. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brancato SK, Albina JE. Wound macrophages as key regulators of repair: origin, phenotype, and function. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauker J. Continuous Glucose Sensing: Future Technology Developments. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2009;11:S25–S36. doi: 10.1089/dia.2008.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton Gn, Janis JE, Attinger CE. The basic science of wound healing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:12S–34S. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000225430.42531.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BN, Ratner BD, Goodman SB, Amar S, Badylak SF. Macrophage polarization: an opportunity for improved outcomes in biomaterials and regenerative medicine. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3792–3802. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet J, Douki T, Ravanat J-L. Measurement of oxidatively generated base damage in cellular DNA. Mutat. Res. Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2011;711:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan DH, Yergey JA, Rousseau P, Masson P. Respiratory tract eicosanoid measurement using microdialysis sampling and GC/MS detection. Pulm. Pharmacol. 1994;7:35–41. doi: 10.1006/pulp.1994.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan MR, Shah MM. Translating biomaterial properties to intracellular signaling. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2009;54:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s12013-009-9048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso CR, Favoreto S, Jr, Oliveira LL, Vancim JO, Barban GB, Ferraz DB, Silva JS. Oleic acid modulation of the immune response in wound healing: A new approach for skin repair. Immunobiology. 2011;216:409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castner DG, Ratner BD. Biomedical surface science: Foundations to frontiers. Surf. Sci. 2002;500:28–60. [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Warden JT, Stenken JA. Microdialysis Sampling Combined with Electron Spin Resonance for Superoxide Radical Detection in Microliter Samples. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:4734–4740. doi: 10.1021/ac035543g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chertok B, Webber MJ, Succi MD, Langer R. Drug Delivery Interfaces in the 21st Century: From Science Fiction Ideas to Viable Technologies. Mol. Pharmaceutics. 2013 doi: 10.1021/mp4003283. Ahead of Print, 10.1021/mp4003283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church MK, Griffiths TJ, Jeffery S, Ravell LC, Cowburn AS, Sampson AP, Clough GF. Are cysteinyl leukotrienes involved in allergic responses in human skin? Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2002;32:1013–1019. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2002.01436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark IM. Matrix Metalloproteinase Protocols, Methods in Molecular Biology. Towata, NJ: Humana Press; 2001. p. 545. [Google Scholar]

- Clark LC, Jr, Lyons C. Electrode systems for continuous monitoring in cardiovascular surgery. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1962;102:29–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb13623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough GF. Microdialysis of large molecules. AAPS J. 2005;7:E686–E692. doi: 10.1208/aapsj070369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough GF, Jackson CL, Lee JJ, Jamal SC, Church MK. What can microdialysis tell us about the temporal and spatial generation of cytokines in allergen-induced responses in human skin in vivo? J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2799–2806. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman DL, King RN, Andrade JD. The foreign body reaction: a chronic inflammatory response. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1974;8:199–211. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820080503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AR, Cadet J, Moeller L, Poulsen HE, Vina J. Are we sure we know how to measure 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine in DNA from human cells? Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2004;423:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius RM, Brash JL. Identification of proteins adsorbed to hemodialyzer membranes from heparinized plasma. J. Biomater. Sci., Polym. Ed. 1993;4:291–304. doi: 10.1163/156856293x00573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce RA, Jr, Vaddiraju S, Kondo J, Wang Y, Zuo L, Zhu K, Islam SK, Burgess DJ, Papadimitrakopoulos F, Jain FC. A miniaturized transcutaneous system for continuous glucose monitoring. Biomed. Microdevices. 2013;15:151–160. doi: 10.1007/s10544-012-9708-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham DD, Stenken JA. In Vivo Glucose Sensing. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlin AP, Hjort K, Hillered L, Sjodin MO, Bergquist J, Wetterhall M. Multiplexed quantification of proteins adsorbed to surface-modified and non-modified microdialysis membranes. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012;402:2057–2067. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5614-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlin AP, Wetterhall M, Caldwell KD, Larsson A, Bergquist J, Hillered L, Hjort K. Methodological Aspects on Microdialysis Protein Sampling and Quantification in Biological Fluids: An In Vitro Study on Human Ventricular CSF. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:4376–4385. doi: 10.1021/ac1007706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang TT, Bratlie KM, Bogatyrev SR, Chen XY, Langer R, Anderson DG. Spatiotemporal effects of a controlled-release anti-inflammatory drug on the cellular dynamics of host response. Biomaterials. 2011;32:4464–4470. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.02.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange ECM, Danhof M, de Boer AG, Breimer DD. Critical factors of intracerebral microdialysis as a technique to determine the pharmacokinetics of drugs in rat brain. Brain Res. 1994;666:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derendorf H, Rohdewald P, Hochhaus G, Möllmann H. HPLC determination of glucocorticoid alcohols, their phosphates and hydrocortisone in aqueous solutions and biological fluids. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1986;4:197–206. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(86)80042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desiss D, Hartmann R, Schmidt J, Kordonouri O. Results of a Randomised Controlled Cross-over Trial on the Effect of Continous Subcutaneous Glucose Monitoring (CGMS) on Glycaemic Control in Children and Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes. 2006;114:63–67. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-923887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugan LL, Lin T-S, He YY, Hsu CY, Choi DW. Detection of free radicals by microdialysis/spin trapping EPR following focal cerebral ischemia-reperfusion and a cautionary note on the stability of 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) Free Radical Res. 1995;23:27–32. doi: 10.3109/10715769509064016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duo J, Stenken JA. Heparin-immobilized microspheres for the capture of cytokines. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011a;399:773–782. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-4170-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duo J, Stenken JA. In vitro and in vivo affinity microdialysis sampling of cytokines using heparin-immobilized microspheres. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2011b;399:783–793. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-4333-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecker J. Profiling eicosanoids and phospholipids using LC-MS/MS: Principles and recent applications. J. Sep. Sci. 2012;35:1227–1235. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201200056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekerfelt C, Ernerudh J, Jenmalm MC. Detection of spontaneous and antigeninduced human interleukin-4 responses in vitro: comparison of ELISPOT, a novel ELISA and real-time RT-PCR. J. Immunol. Methods. 2002;260:55–67. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(01)00520-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmquist WF, Sawchuk RJ. Application of microdialysis in pharmacokinetic studies. Pharm. Res. 1997;14:267–288. doi: 10.1023/a:1012081501464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eming SA, Hammerschmidt M, Krieg T, Roers A. Interrelation of immunity and tissue repair or regeneration. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2009;20:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folco G, Murphy RC. Eicosanoid transcellular biosynthesis: from cell-cell interactions to in vivo tissue responses. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006;58:375–388. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser DM. Biosensors in the Body, Continuous in vivo Monitoring. Chichester UK: John Wiley and Sons; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia AJ. Get a grip: integrins in cell-biomaterial interactions. Biomaterials. 2005;26:7525–7529. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford R, Batchelor MM, Lee Y, Gokulrangan G, Meyerhoff ME, Wilson GS. Mediation of in vivo glucose sensor inflammatory response via nitric oxide release. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A. 2005;75A:755–766. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan BC, Shults M, Rhodes RK, Jacobs PG, Brauker JH, Pintar TJ, Updike SJ. Feasibility of continuous long-term glucose monitoring from a subcutaneous glucose sensor in humans. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2004;6:378–386. doi: 10.1089/152091504774198089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough DA, Armour JC. Development of the implantable glucose sensor. What are the prospects and why is it taking so long? Diabetes. 1995;44:1005–1009. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.9.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouwy M, Struyf S, Proost P, Van Damme J. Synergy in cytokine and chemokine networks amplifies the inflammatory response. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:561–580. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, Longaker MT. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453:314–321. doi: 10.1038/nature07039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarlund-Udenaes M. The use of microdialysis in CNS drug delivery studies. Pharmacokinetic perspectives and results with analgesics and antiepileptics. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2000;45:283–294. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedenberg-Magnusson B, Ernberg M, Alstergren P, Kopp S. Pain mediation by prostaglandin E2 and leukotriene B4 in the human masseter muscle. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2001;59:348–355. doi: 10.1080/000163501317153185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedenberg-Magnusson B, Ernberg M, Alstergren P, Kopp S. Effect on prostaglandin E2 and leukotriene B4 levels by local administration of glucocorticoid in human masseter muscle myalgia. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2002;60:29–36. doi: 10.1080/000163502753471970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henninger N, Woderer S, Kloetzer HM, Staib A, Gillen R, Li L, Yu X, Gretz N, Kraenzlin B, Pill J. Tissue response to subcutaneous implantation of glucoseoxidase- based glucose sensors in rats. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;23:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetrick EM, Prichard HL, Klitzman B, Schoenfisch MH. Reduced foreign body response at nitric oxide-releasing subcutaneous implants. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4571–4580. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heydari Nasrabadi M, Tajabadi Ebrahimi M, Dehghan Banadaki Sh, Torabi Kajousangi M, Zahedi F. Study of cutaneous wound healing in rats treated with Lactobacillus plantarum on days 1, 3, 7, 14, and 21. African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2011;5:2395–2401. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey T, Kreutzer D, Burgess DJ, Moussy F. In vivo evaluation of a dexamethasone/PLGA microsphere system designed to suppress the inflammatory tissue response to implantable medical devices. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2002;61:180–187. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DM, Basaraba RJ, Hohnbaum AC, Lee EJ, Grainger DW, Gonzalez- Juarrero M. Localized immunosuppressive environment in the foreign body response to implanted biomaterials. Am. J. Pathol. 2009;175:161–170. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama Y, Oda S, Wakabayashi K, Sadahiro T, Nakamura M, Watanabe E, Tateishi Y. Comparison of Interleukin-6 Removal Properties among Hemofilters Consisting of Varying Membrane Materials and Surface Areas: An in vitro Study. Blood Purif. 2011;31:18–25. doi: 10.1159/000321142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt JA, McLaughlin PJ, Flanagan BF. Techniques to investigate cellular and molecular interactions in the host response to implanted biomaterials. Biomaterials. 1997;18:1449–1459. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer SS, Barr WH, Karnes HT. Profiling in vitro drug release from subcutaneous implants: a review of current status and potential implications on drug product development. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2006;27:157–170. doi: 10.1002/bdd.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janis JE, Kwon RK, Lalonde DH. A practical guide to wound healing. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2010;125:230e–244e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181d9a0d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JA, McNally AK, Chang DT, Qin LA, Meyerson H, Colton E, Kwon IL, Matsuda T, Anderson JM. Matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in the foreign body reaction on biomaterials. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;84:158–166. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KS. Effects of biomaterial-induced inflammation on fibrosis and rejection. Semin. Immunol. 2008;20:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junge K, Binnebosel M, von Trotha KT, Rosch R, Klinge U, Neumann UP, Lynen Jansen P. Mesh biocompatibility: effects of cellular inflammation and tissue remodelling. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2012;397:255–270. doi: 10.1007/s00423-011-0780-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick KM. Microdialysis measurement of in vivo neuropeptide release. J. Neurosci. Methods. 1990;34:35–46. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(90)90040-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan OF, Jean-Francois J, Sefton MV. MMP levels in the response to degradable implants in the presence of a hydroxamate-based matrix metalloproteinase sequestering biomaterial in vivo. J. Biomed. Mater. Res, Part A FIELD Full Journal Title: Journal of Biomedical Materials Research, Part A. 2010;93A:1368–1379. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ND, Luster AD. Regulation of immune cells by eicosanoid receptors. TheScientificWorld FIELD Full Journal Title:TheScientificWorld. 2007;7:1307–1328. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjellstrom S, Emneus J, Laurell T, Heintz L, Marko-Varga G. Online coupling of microdialysis sampling with liquid chromatography for the determination of peptide and non-peptide leukotrienes. J. Chromatogr. A. 1998;823:489–496. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(98)00361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klueh U, Dorsky DI, Kreutzer DL. Enhancement of implantable glucose sensor function in vivo using gene transfer-induced neovascularization. Biomaterials. 2004;26:1155–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klueh U, Kaur M, Montrose DC, Kreutzer DL. Inflammation and glucose sensors: use of dexamethasone to extend glucose sensor function and life span in vivo. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2007;1:496–504. doi: 10.1177/193229680700100407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kou PM, Babensee JE. Macrophage and dendritic cell phenotypic diversity in the context of biomaterials. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2011;96:239–260. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumlin M. Analytical methods for the measurement of leukotrienes and other eicosanoids in biological samples from asthmatic subjects. J Chromatogr A. 1996;725:29–40. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(95)01125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WF, Ma M, Bratlie KM, Dang TT, Langer R, Anderson DG. Realtime in vivo detection of biomaterial-induced reactive oxygen species. Biomaterials FIELD Full Journal Title:Biomaterials. 2011;32:1796–1801. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonnroth P, Jansson PA, Smith U. A microdialysis method allowing characterization of intercellular water space in humans. Am J Physiol FIELD Full Journal Title:The American journal of physiology. 1987;253:E228–E231. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1987.253.2.E228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunte CE, Scott DO, Kissinger PT. Sampling living systems using microdialysis probes. Anal. Chem. 1991;63:773A–774A. 776A–778A, 780A. [Google Scholar]

- Luttikhuizen DT, Harmsen MC, Van Luyn MJ. Cellular and molecular dynamics in the foreign body reaction. Tissue Eng. 2006a;12:1955–1970. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttikhuizen DT, Van Amerongen MJ, De Feijter PC, Petersen AH, Harmsen MC, Van Luyn MJA. The correlation between difference in foreign body reaction between implant locations and cytokine and MMP expression. Biomaterials. 2006b;27:5763–5770. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddipati KR, Zhou S-L. Stability and analysis of eicosanoids and docosanoids in tissue culture media. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediators. 2011;94:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Sica A, Locati M. Macrophage polarization comes of age. Immunity. 2005;23:344–346. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004a;25:677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004b;25:677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant RE. The cage implant system for determining in vivo biocompatibility of medical device materials. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1989;13:217–227. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(89)90258-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]