Abstract

Avondale, a disadvantaged neighborhood in Cincinnati, lags behind on a number of indicators of child well-being. Childhood obesity has become increasingly prevalent, as one third of Avondale’s kindergarteners are obese or overweight. The study objective was to determine perceptions of the quantity of and obstacles to childhood physical activity in the Avondale community. Caregivers of children from two elementary schools were surveyed to assess their child’s physical activity and barriers to being active. Three hundred forty surveys were returned out of 1,047 for a response rate of 32%. On school days, 41% of caregivers reported that their children spent more than 2 hours watching television, playing video games, or spending time on the computer. While over half of respondents reported that their children get more than 2 hours of physical activity on school days, 14% of children were reported to be physically active less than 1 hour per day. Caregivers identified violence, cost of extracurricular activities, and lack of organized activities as barriers to their child’s physical activity. The overwhelming majority of caregivers expressed interest in a program to make local playgrounds safer. In conclusion, children in Avondale are not participating in enough physical activity and are exposed to more screen time than is recommended by the AAP. Safety concerns were identified as a critical barrier to address in future advocacy efforts in this community. This project represents an important step toward increasing the physical activity of children in Avondale and engaging the local community.

Keywords: Physical activity, community engagement, 5-2-1-0, advocacy

Introduction

Physical activity is a critical part of healthy development in children.1–3 Previous studies have identified key factors that influence the activity level of children,4–6 but only a minority of reports have assessed children from low-income, inner city neighborhoods.7, 8 While substantial investments have been made in advocacy projects aimed at improving child health in underprivileged neighborhoods, these projects have not demonstrated meaningful improvements in measurable outcomes such as body mass index (BMI) and objective measures of child physical activity.9–12

Avondale, a disadvantaged neighborhood in Cincinnati, lags far behind the remainder of the city and Hamilton County on a number of indicators of child well-being.13 More than 40 percent of children growing up in the Avondale community of Cincinnati, Ohio live at or below the poverty level.14 A recent study of children in Ohio demonstrates that low-income children are significantly more likely to be obese compared to other children.15 Indeed, childhood obesity has become increasingly prevalent in Avondale, as one third of Avondale’s kindergarteners are obese or overweight.15 Once known for its crime and violence statistics, community leaders have been working for almost a decade to rejuvenate the Avondale area which has led to marked decline in crime and murder rates.16–18

Previous studies indicate advocacy projects focused on childhood obesity have potential for successful outcomes if they are tailored to the specific needs of a community and can be implemented on a foundation of parental engagement.15, 19, 20 The importance of community and parental engagement and identification of barriers prohibiting such behaviors as physical activity should not be underestimated.21 The purpose of this study was to determine community perceptions of the quantity of and obstacles to childhood physical activity while collecting specific ideas for advocacy.

Methods

Context

The analyses presented are based upon data collected through an advocacy project called Avondale Moves! (www.avondalemoves.org). Avondale Moves! is an organization dedicated to increasing safe, active play in Avondale’s youth and was founded by a pediatrics resident at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC). Avondale Moves! strongly endorses the 5-2-1-0 program from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).22, 23 The program involves eating 5 fruits or vegetables, watching less than 2 hours of TV, exercising for 1 hour or more, and drinking 0 sugary drinks every day.23 Avondale Moves! is funded by a Resident Community Access to Child Health (CATCH) grant through the AAP. This study was approved by the CCHMC institutional review board and the Cincinnati Public Schools research approval committee.

Participants

Surveys were sent to the parents and guardians of children attending Rockdale Elementary (560 distributed surveys) and South Avondale Elementary (487 distributed surveys) schools. These two public schools are the only elementary schools located in Avondale and serve grades K-8 (at the time of the study). The surveys were distributed to every classroom and collected in the third week of October, 2012. An incentive was given to the classrooms at each school with the highest rate of completed surveys. Participants for community meetings were recruited through flyers and e-mails sent to parents and guardians of children who attended Rockdale Elementary and South Avondale Elementary. Meetings were held after the survey distribution and did not inform the content of the instrument. The meetings were conducted with the goal of sharing the results of the survey with parents, guardians, and community members. G. Kottyan was the facilitator and delivered a 30-minute presentation followed by a period of dialog that included questions and suggestions. Forty-two adults in total attended two meetings, which were held within a one-week period. Additional presentations were held for Avondale Community Council and Citizens on Patrol organizations. Food and water was provided at each community meeting.

Survey

Caregivers of children from Rockdale and South Avondale Elementary schools were asked to complete an 11-item survey. The majority of the items on the survey were multiple-choice questions. The instrument was designed to collect data regarding the physical activity (organized sports and outside play) and inactivity (television watching and video game playing) of the specified population. Furthermore, the survey included questions aimed at identifying barriers to physical activity and a fill-in question with the intent of gathering information on the specific needs of the community to increase physical activity. The survey was developed de novo for this project and reviewed internally by 10 medical center child health professionals including clinicians and researchers at CCHMC. The reproducibility of the survey was assessed, in part, through comparing the results from the two independent elementary schools.

Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA). Survey results were entered twice by creating two identical blank data entry spreadsheets at two separate times using a standard method.24 Means and proportions were calculated and graphed.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Of the 560 surveys distributed, 190 surveys were returned from South Avondale Elementary School (response rate = 34%). The households represented in these surveys had 2.3 ± 1. (mean ± standard deviation) children age 8.0 ± 3 years. From Rockdale Elementary school, 150 of the 487 distributed surveys were returned (response rate = 30%). The Average number of children in the households was 2.1 ± 1 and the average age of the children was 6.4 ± 3.

Subjective Reports of Child Activity

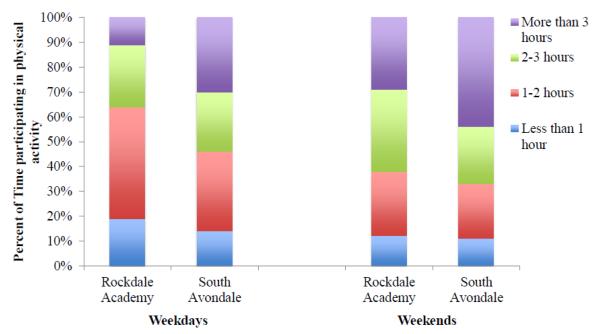

Forty-six percent of all caregivers surveyed reported that their children get more than 2 hours of physical activity on school days (36% and 54% for Rockdale Elementary and South Avondale Elementary caregivers, respectively) (Figure 1A). Conversely, 16% of respondents stated that their child gets less than the recommended 1 hour of physical activity on school days (19% versus 14% of Rockdale Elementary and South Avondale Elementary caregivers respectively) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Subjective Reports of Physical Activity.

Parents and guardians answered the survey questions “How many hours per day does your child play outside or participate in organized physical activity (sports, dance, cheerleading etc.) on school days (A) or the weekend (B)?”. Respondents were given four choices as shown in each stacked bar graph.

On the weekends, the amount of reported physical activity was significantly greater than weekdays (p-value<0.001) with 64% of respondents stating that their child gets more than 2 hours of physical activity on weekends (62% versus 67% of Rockdale Elementary and South Avondale Elementary caregivers respectively). However, 12% of respondents stated that their child gets less than the AAP recommended 1 hour of physical activity on weekend days (12% versus 11% of Rockdale Elementary and South Avondale Elementary caregivers respectively) (Figure 1B).

Subjective Reports of Child Inactivity

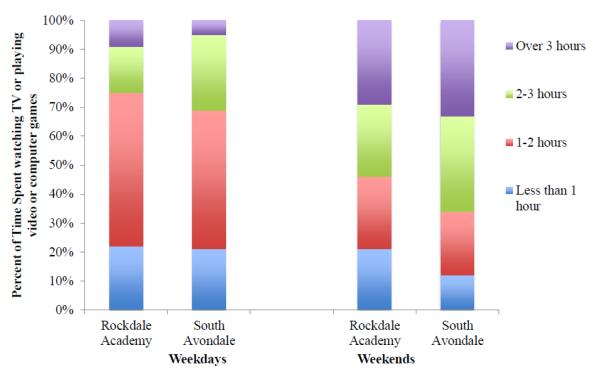

Forty-one percent of caregivers reported that their children spent more than the recommended maximum 2 hours watching television (TV), playing video games, or spending time on the computer on school days (25% versus 54% of Rockdale Elementary and South Avondale Elementary caregivers respectively) (Figure 2A). The most common response at both schools was that children were getting 1-2 hours of screen time on most school days (52% versus 48% of Rockdale Elementary and South Avondale Elementary caregivers respectively) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Subjective Reports of Physical Inactivity.

Parents and guardians answered the survey questions “How many hours per day does your child watch TV or play video/computer games on school days (A) or the weekend (B)?”. Respondents were given four choices as shown in a stacked bar graph.

Caregivers reported a significantly increased screen time (p-value<0.001) on non-school days with 50% of respondents saying that children spend more than the AAP-recommended 2 hours in front of a screen on weekends (31% versus 66% of Rockdale Elementary and South Avondale Elementary caregivers respectively) (Figure 2B).

Obstacles and barriers to physical activity

The three most commonly selected responses to the question “What are the biggest obstacles in getting enough physical exercise for your child?” were that the neighborhood is not safe enough for kids to play outside (50% of respondents) followed by not enough organized sports and activities (45% of respondents) and the financial cost of participation in physical activities (38% of respondents).

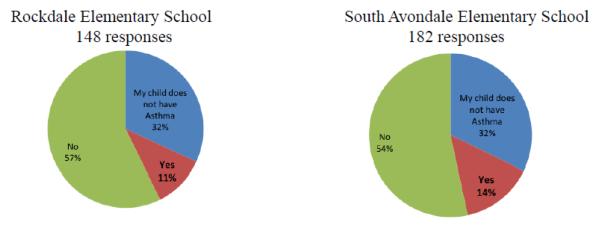

In addition, 12.3% of parents and guardians of children in Avondale elementary schools who were surveyed reported that asthma prevents their child from exercising or playing outside (14% versus 11% of Rockdale Elementary and South Avondale Elementary caregivers respectively) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Perceptions of Obstacles and barriers to Physical Inactivity.

Parents and guardians of children in Rockdale Elementary School and South Avondale Elementary School answered the survey question “Does Asthma prevent your child from exercising or playing outside?”. Respondents were given three choices as shown in each pie chart.

We included one free-response question on the survey with the purpose of collecting ideas that originate in the community for advocacy projects. The most common suggestions were to 1) reduce violence (n=31), 2) make more activities available and affordable (n=54), and 3) make the existing play areas safer (n=73).

Underscoring the importance of safe play spaces for their children, 65% of parents and guardians expressed an interest in a program that would make local playgrounds safer (62% versus 72% of Rockdale Elementary and South Avondale Elementary caregivers respectively).

Community Meetings: Reactions and Common Concerns

We returned to both elementary schools to share the results of the survey and collect more ideas from the community of parents and guardians. We found that many parents cared deeply about the physical health of their children and caregivers shared sentiments that their children had fewer opportunities and more barriers to physical activity than children in more affluent communities. The results of the survey resonated with the community groups and they added specific details and concerns to those that we found in the survey results. For example, the local recreation center is underfunded and has extremely limited hours compared to other recreation centers around Cincinnati. Furthermore, there was a general consensus that there are very few organized activities for older children and teens, especially girls.

Community Engagement

Proceeding from the community meetings, we shared the results with community leaders and representatives of several other Avondale groups. The Citizens on Patrol of Avondale is a neighborhood watch group consisting of community members who patrol the neighborhood and report crime to the Cincinnati Police Department. Citizens on Patrol group members were encouraged and supportive of the results of this survey and volunteered to partner with Avondale Moves! to create safe play-days at local playgrounds. These days will be advertised to encourage caregivers to bring their children to a park surrounded by community members and a paid off-duty police officer. Each event will include opportunities for free play on playground equipment and impromptu sports games using equipment provided by Avondale Moves!. These safe play days have been modeled after a very successful program in Kennedy Heights, another Cincinnati community in which violence is a barrier to children playing at the local playground. The Avondale Community Council is an elected group of leaders who promote the community and provide leadership. During a presentation to this council, we were encouraged to connect with the Avondale Youth Council and a well-established, city wide advocacy organization called Center for Closing the Health Gap. Through these connections, we have built a core group of parents, community leaders, and CCHMC representatives who are dedicated to increasing safe, active play in the children of the Avondale community.

Discussion

In this study, we highlighted caregiver subjective reports regarding the amount of physical activity and inactivity of children at two elementary schools in the community of Avondale, Ohio. Many organizations including the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention have recognized daily active play as an important part of childhood, yet most national studies have repeatedly found that children are not getting enough physical activity.3, 15, 25–27 Our study indicates that a number of children within Avondale are not getting enough physical activity and exposed to excessive screen time. Specifically, nearly 1 in 5 caregivers reported that their child does not receive the recommended one-hour of physical activity each day and over half of caregivers reported their child gets more than the recommended amount of screen time. Our findings of physical activity and screen time are consistent with those found in previous studies.25, 26, 28 For example a statewide survey of parents from neighboring Kentucky found that 56% of caregivers reported their children get more than the recommended 2 hour maximum of screen time and 34% reported that their children do not get the recommended amount of physical activity.28 These independent studies support the need for future advocacy projects aimed at improving child health through increasing physical activity and decreasing screen time. Furthermore, our study indicates that caregivers perceive safety as the largest barrier to active play by their children, which is a finding of similar studies in other inner city neighborhoods.5, 25, 29–31 Caregivers of Avondale were less concerned about the risk of their children sustaining injuries on a playground and more concerned with the risk of their children becoming victims of acts of random violence. The desire for children to be safe is vitally important to caregivers and focusing on removing this barrier could potentially increase the success of future interventions.25, 31 Through community engagement, we have established a plan to provide opportunities for supervised safe play days at a local playground. To date, 23 local community members have volunteered to coordinate and attend our upcoming safe play days. These types of safe play days have already demonstrated encouragingly successfully results in early pilot studies in similar neighborhoods.20

Parents and guardians in this study cited the economic cost of physical activity as a barrier. It is not surprising that financial concerns can prevent children from participating in aerobic activities, as this barrier has been identified by national studies and studies of similar neighborhoods.29, 32,33 For example, when parents are making inexpensive child care arrangements, they are often happy to find a safe place for their children. Understandably, parents with limited options may not prioritize active play when they are balancing safety and financial concerns. Finances also limit families’ options when they are looking for outdoor play areas.32 For families living below the poverty line, any distance greater than one-mile and any gym or community center membership fee represent substantial barriers to activity.33 The options that these families have are limited especially in an economy that has led to the closure and consolidation of community recreation centers in the city of Cincinnati. Avondale residents primarily have access to the Hirsch Recreation Center, located in Avondale. While it is inexpensive to join and provides valuable services to the community including after-school programming, it is relatively small compared to recreation centers in comparably sized communities and the hours are extremely limited (closed on weekends).

This study is not without limitations. Less than one half of the caregivers returned the surveys for analysis in this study, which may have led to a respondent bias in that caregivers who responded are likely more engaged and invested in the items highlighted in the survey. The distribution and collection of the surveys depended on the children at each elementary school. Each child was handed the survey with the expectation that the survey would be given to their caregiver and brought back to school completed. Some caregivers may have never received the survey or some children may have forgotten to hand in completed surveys. . Furthermore, the results of the survey may be affected by recall bias as it highlights the subjective reports of caregivers and might not be representative of the actual time their children spend in active and inactive activities. Physical activity may have been overestimated and inactivity underestimated especially given the time of year when the surveys were collected. Although the validity of the particular survey questions used in this study has not been assessed, the questions were similar to surveys used nationally.27 Despite these limitations, we are highly encouraged by the consistency of responses between the two schools. The small differences that we identified (e.g. the distribution of students who spend 1-2, 2-3 and 3 or more hours a day in physical activity, Figure 2) probably reflect the difference in the mean age of the children from the two schools. The results of this study also provide a strong rationale for follow-up studies using quantitative measures of physical activity and for specific, community-driven family-centered interventions.

Avondale is an energetic community primed to make substantial investments in their children’s health. Community organizations have focused their attention on advocacy initiatives that benefit all residents of Avondale including children; future efforts will hopefully address gaps and barriers that may hinder continued progress. Our goal will be to facilitate and encourage the important work of these community partners and to implement initiatives in a way that is community-driven and well received.

Conclusions

Caregivers of children from two elementary schools in Avondale reported over one-half of children were spending more than the recommended 2 hour maximum of screen time. Respondents also reported nearly 1 in 5 children did not get the AAP-recommended one-hour of physical activity each day. Safety was the most commonly cited barrier to child activity in Avondale, Ohio. Survey results were shared with the residents of Avondale and have inspired endeavors to partner with community organizations and facilitate an environment for safe and active play for children. The next step in this neighborhood is a community-supported Safe Play Days program, which will give chaperoned opportunities for community children to play in local playgrounds.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: American Academy of Pediatrics Resident CATCH Grant NIH NCRR/NCATS KL2 TR000078

Abbreviations

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- CCHMC

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

- CATCH grant

Community Access to Child Health grant

- TV

Television

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Boreham C, Riddoch C. The physical activity, fitness and health of children. Journal of sports sciences. 2001;19(12):915–929. doi: 10.1080/026404101317108426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Service UPH, editor. Physical activity and health: a report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Services USDoHaH, editor. Physical activity guidelines for Americans: be active, healthy, and happy! Dept. of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicaise V, Kahan D, Sallis JF. Correlates of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity among preschoolers during unstructured outdoor play periods. Preventive medicine. 2011;53(4-5):309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, Taylor WC, Hill JO, Geraci JC. Correlates of physical activity in a national sample of girls and boys in grades 4 through 12. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 1999;18(4):410–415. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.4.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barr-Anderson DJ, Young DR, Sallis JF, Neumark-Sztainer DR, Gittelsohn J, Webber L, et al. Structured physical activity and psychosocial correlates in middle-school girls. Preventive medicine. 2007;44(5):404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Long MW, Sobol AM, Cradock AL, Subramanian SV, Blendon RJ, Gortmaker SL. School-day and overall physical activity among youth. American journal of preventive medicine. 2013;45(2):150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lafleur M, Gonzalez E, Schwarte L, Banthia R, Kuo T, Verderber J, et al. Increasing physical activity in under-resourced communities through school-based, joint-use agreements, Los Angeles County, 2010-2012. Preventing chronic disease. 2013;10:E89. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown H, Hume C, Pearson N, Salmon J. A systematic review of intervention effects on potential mediators of children’s physical activity. BMC public health. 2013;13:165. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone EJ, McKenzie TL, Welk GJ, Booth ML. Effects of physical activity interventions in youth. Review and synthesis. American journal of preventive medicine. 1998;15(4):298–315. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Sluijs EM, McMinn AM, Griffin SJ. Effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity in children and adolescents: systematic review of controlled trials. Bmj. 2007;335(7622):703. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39320.843947.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salmon J, Booth ML, Phongsavan P, Murphy N, Timperio A. Promoting physical activity participation among children and adolescents. Epidemiologic reviews. 2007;29:144–159. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Center CPR, editor. Taking Action to Prevent Infant Death in Hamilton County. Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bureau USC, editor. 2010 Census. U.S. Census Bureau; 2010. http://www.census.gov/2010census/data/ [Google Scholar]

- 15.(CDC) CfDCaP; National CfHSN, editor. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data, 2005-2008. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Hyattsville, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madensen T. Avondale Crime Reduction Project: Ohio Service for Crime Opportunity Reduction: Division of Criminal Justice. University of Cincinnati; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arora P. Burnet Avenue, Avondale Neighborhood Cincinnati, Ohio Revitalization Strategy. University of Cincinnati; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engel RS, Corsaro N, Tillyer MS. Evaluation of the Cincinnati Initiative to Reduce Violence (CIRV) University of Cincinnati; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golan M. Parents as agents of change in childhood obesity–from research to practice. International journal of pediatric obesity : IJPO : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2006;1(2):66–76. doi: 10.1080/17477160600644272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farley TA, Meriwether RA, Baker ET, Watkins LT, Johnson CC, Webber LS. Safe play spaces to promote physical activity in inner-city children: results from a pilot study of an environmental intervention. American journal of public health. 2007;97(9):1625–1631. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.092692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gittelman MA, Pomerantz WJ. The Use of Focus Groups to Mobilize a High-Risk Community in an Effort to Prevent Injuries. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community. 2011;39:209–222. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2011.576964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis MM, Gance-Cleveland B, Hassink S, Johnson R, Paradis G, Resnicow K. Recommendations for prevention of childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):S229–253. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barlow SE, Expert C. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):S164–192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elliott AC, Hynan LS, Reisch JS, Smith JP. Preparing data for analysis using microsoft Excel. Journal of investigative medicine : the official publication of the American Federation for Clinical Research. 2006;54(6):334–341. doi: 10.2310/6650.2006.05038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sallis JF, Nader PR, Broyles SL, Berry CC, Elder JP, McKenzie TL, et al. Correlates of physical activity at home in Mexican-American and Anglo-American preschool children. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 1993;12(5):390–398. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.5.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salmon J, Veitch J, Abbott G, Chinapaw M, Brug JJ, Tevelde SJ, et al. Are associations between the perceived home and neighbourhood environment and children’s physical activity and sedentary behaviour moderated by urban/rural location? Health & place. 2013;24C:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prevention CfDCa, editor. Physical Activity Levels of High School Students-United States, 2010. M: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report; 2011. pp. 773–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kentucky FfaH., editor. Results from the 2012 Kentucky Parent Survey: Statewide Summary. Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky; Louisville, KY: 20012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prevention CfDCa, editor. Neighborhood safety and prevalence of physical inactivity–selected states, 1996. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999. pp. 143–146. [PubMed]

- 30.Baranowski T, Thompson WO, DuRant RH, Baranowski J, Puhl J. Observations on physical activity in physical locations: age, gender, ethnicity, and month effects. Research quarterly for exercise and sport. 1993;64(2):127–133. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1993.10608789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sallis JF, McKenzie TL, Elder JP, Broyles SL, Nader PR. Factors parents use in selecting play spaces for young children. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 1997;151(4):414–417. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170410088012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Irwin JD, He M, Bouck LM, Tucker P, Pollett GL. Preschoolers’ physical activity behaviours: parents’ perspectives. Canadian journal of public health = Revue canadienne de sante publique. 2005;96(4):299–303. doi: 10.1007/BF03405170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krans EE, Chang JC. A will without a way: barriers and facilitators to exercise during pregnancy of low-income, African American women. Women & health. 2011;51(8):777–794. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2011.633598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]