Abstract

Antimetabolite chemotherapy remains an essential cancer treatment modality, but often produces only marginal benefit due to the lack of tumor specificity, the development of drug resistance, and the refractoriness of slowly-proliferating cells in solid tumors. Here, we report a novel strategy to circumvent the proliferation-dependence of traditional antimetabolite-based therapies. Triplex-forming oligonucleotides (TFOs) were used to target site-specific DNA damage to the human c-MYC oncogene, thereby inducing replication-independent, unscheduled DNA repair synthesis (UDS) preferentially in the TFO-targeted region. The TFO-directed UDS facilitated incorporation of the antimetabolite, gemcitabine (GEM), into the damaged oncogene, thereby potentiating the anti-tumor activity of GEM. Mice bearing COLO 320DM human colon cancer xenografts (containing amplified c-MYC) were treated with a TFO targeted to c-MYC in combination with GEM. Tumor growth inhibition produced by the combination was significantly greater than with either TFO or GEM alone. Specific TFO binding to the genomic c-MYC gene was demonstrated, and TFO-induced DNA damage was confirmed by NBS1 accumulation, supporting a mechanism of enhanced efficacy of GEM via TFO-targeted DNA damage-induced UDS. Thus, coupling antimetabolite chemotherapeutics with a strategy that facilitates selective targeting of cells containing amplification of cancer-relevant genes can improve their activity against solid tumors, while possibly minimizing host toxicity.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the United States, and it has been estimated that nearly 1.6 million new cases would be diagnosed in 2011 [1]. The drugs of first choice for some cancers depend on the hormone receptor status of the tumor cells or on the expression of a specific drug target. However, in the absence of such specific cellular determinants, cytotoxic chemotherapy is often required. Among the cytotoxic agents in clinical use are DNA interactive/modifying agents, tubulin active agents, and antimetabolites. The cytotoxic activity of DNA antimetabolites is generally restricted to proliferating cells. A notable exception, Gemcitabine (GEM), a cytosine analog, is toxic to non-cycling as well as proliferating cells although one of its primary modes of anticancer action involves its incorporation into the DNA of the cancer cell [2,3]. Given the clinical relevance of GEM for treatment of several solid tumors, we were interested in whether increasing its incorporation into DNA of cancer cells would improve its effectiveness. We now report our studies on a novel strategy that may improve the outcome of GEM-based anticancer regimens and also may overcome the cell-cycle-dependent nature of many anticancer agents.

Genetic abnormalities in solid tumors include amplification of oncogenes (e.g., MYC in numerous cancer types, ERB-B2 in breast and ovarian cancer, AKT2 in ovarian cancer, MYCL1 in small cell lung cancer and medulloblastoma, MYCN in neuroblastoma) [4] and elevated levels of oncoproteins are often detected in primary tumors and may correlate with poor prognosis. These oncogenes have the potential to provide excellent targets for the treatment of cancer, as has been demonstrated by the effectiveness of a monoclonal antibody against the HER2/neu protein in patients with metastatic breast cancer [5–7].

Triplex technology offers an exciting approach to specifically target oncogenes for therapeutic intervention. TFOs bind duplex DNA with sequence specificity, forming triple-helical DNA structures. The binding specificity occurs via Hoogsteen hydrogen bonding in the major groove with the purine-rich strand of the underlying target duplex [8,9]. We have shown that triplex formation can be used to direct site-specific DNA damage to stimulate UDS as indicated by specific incorporation of nucleotides into triplex-target sites in plasmids [10]. Nucleotide incorporation in the region of the triplex structure is thought to be due to induction of nucleotide excision repair (NER) synthesis [11–13]. Triplex target sites occur in the human c-MYC gene, and we and others have shown that triplex formation at these sites can inhibit transcription in vitro [8,14] and in cells [10,15–17]. In addition, triplex formation in the c-MYC gene can result in anti-proliferative activity in leukemia cells [18], ovarian and cervical carcinomas [19] and breast cancer cells [10,16]. We have demonstrated that triplexes can induce site-specific mutations in cells and in mice, thus directly inactivating the target gene of interest [20,21].

The pyrimidine antimetabolite, gemcitabine, 2′2′-difluoro-2′-deoxycytidine (GEM), is phosphorylated intracellularly to generate the active metabolites, GEM diphosphate and GEM triphosphate [22]. The diphosphate, as an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase, reduces normal deoxynucleotide pools, allowing for more rapid phosphorylation of GEM and its decreased metabolic clearance [23]. The triphosphate, once incorporated into DNA, is a potent inhibitor of DNA synthesis and induces apoptosis [3,24]. GEM has significant activity against a broad spectrum of tumors when used as a single agent and can show synergistic antitumor activity in combination with DNA-damaging agents [25–28].

Previously, we demonstrated that TFOs can increase the incorporation of GEM into triplex target sites on plasmid DNA in human cell extracts and can also increase the cytotoxic effect of GEM on human cancer cells [10]. We hypothesized that TFOs specifically targeting oncogenes that are amplified in a particular tumor could improve the efficacy of antimetabolites such as GEM against solid tumors in animals. In support of this notion, clinical trials with combinations of antimetabolite nucleoside analogs and DNA-damaging agents have shown promise in low growth-fraction tumors [29–32].

Herein, we demonstrate, using a mouse model of a human colon cancer that has amplification of the c-MYC oncogene, that when a TFO specifically targeting the P2 promoter region of c-MYC is combined with GEM, superior antitumor activity is achieved over that produced by either agent alone. Thus, we demonstrate, for the first time, that the anti-tumor activity of GEM can be potentiated when combined with a TFO targeting an amplified oncogene in animals. In addition, using human tumor cells, we demonstrate that the TFO directly binds to its target in genomic DNA and stimulates GEM incorporation at the TFO-targeted site in cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotides and gemcitabine

The specific triplex-forming oligonucleotide Myc2T (3’ TGGGTGGGTGGTTTGTTTTTGGG 5’) binds the promoter 2 region of the human c-MYC gene [10,17,18]. The non-specific control oligonucleotide, TFOc (3’ GGTGTGTGGTGTGGGTGGG 5’), was designed with a scrambled sequence (Figure 1). Oligonucleotides were synthesized and purified by TriLink BioTechnologies (San Diego, CA). To inhibit degradation in vivo, oligonucleotides were synthesized with a 3’-propanolamine modification unless specified otherwise [33]. 5’-Psoralen-modified oligonucleotides were synthesized using 2-[4’-(hydroxymethyl)-4,5’,8-trimethylpsoralen]-hexyl-1-O-(2-cyanoethyl)-(N,N-diisopropyl)-phosphoramidite (Midland Certified Reagent Company, Midland, TX). pMyc2T-bio and pTFOc-bio were synthesized with a 3’-biotin. Gemcitabine (GEM) was purchased from Eli Lilly (Indianapolis, IN), and was dissolved in sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) prior to use. [3H]GEM was purchased from Moravek Biochemicals and Radiochemicals (Brea, CA).

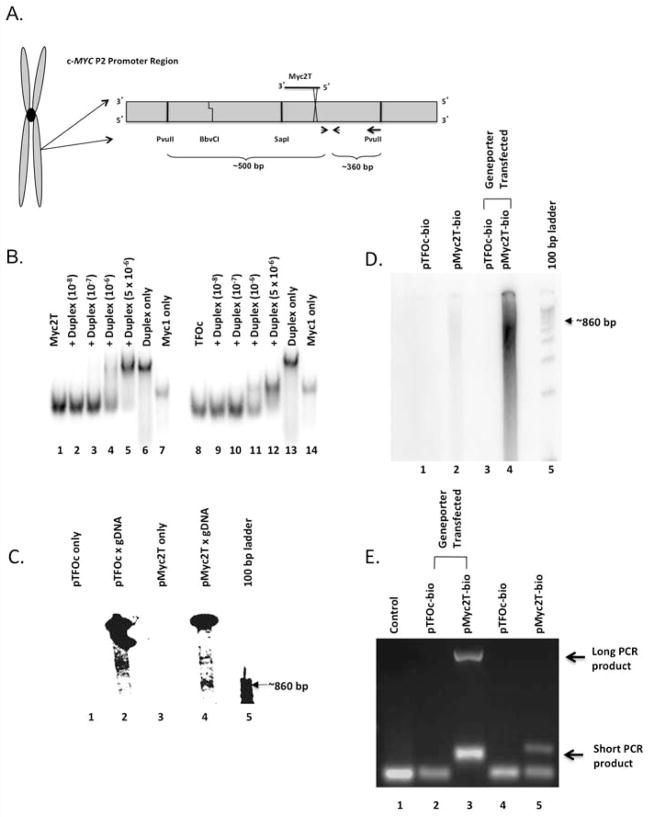

Figure 1.

Specific binding of Myc2T to genomic DNA in vitro and in vivo. (A) Schematic of the Myc2T binding domain. The “X” indicates the psoralen-crosslinking site, and arrows represent PCR primers. (B) Binding assays were performed using radiolabeled TFO Myc2T (lanes 1–7) or control oligonucleotide TFOc (lanes 8–14). (C) pMyc2T (lanes 3 and 4), and control pTFOc (lanes 1 and 2) were incubated with COLO 320DM genomic DNA (gDNA) followed by UVA irradiation (lanes 2 and 4). (D) pTFOc-bio (lanes 1 and 3) and pMyc2T-bio (lanes 2 and 4) were administered passively (lanes 1 and 2) or with a transfection reagent (lanes 3 and 4) into COLO 320DM cells. DNA was analyzed on a native polyacrylamide gel. (E) DNA from Figure 1D was PCR amplified, and the products were visualized on an agarose gel.

Cell culture

COLO 320DM human colon cancer cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) on January 12, 2010 using catalog number CCL-220 (Manassas, VA). The cell line was authenticated using short tandem repeat analysis performed by ATCC. All experiments were conducted within 6 months of resuscitation of the cell line. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 2.5 mg/ml glucose.

Mice

Female athymic NCr-nu/nu mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute at Frederick (Frederick, MD). Mice were allowed to acclimate for one week following arrival before any experimental procedures were performed. Mice were given food and water ad libitum. Experimental procedures involving mice were approved by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and The University of Texas at Austin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

TFO binding assays

EMSA assays were performed as previously described [10]. Genomic DNA was isolated from 1.5×106 COLO 320DM cells and digested with PvuII and RsaI to release an ~862 bp fragment containing the c-MYC TFO binding site. 3’-end radiolabeled oligonucleotides (~10−6 M) containing 5’-psoralen modifications were incubated with 20 μg genomic DNA in triplex binding buffer (10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.6) and irradiated with 1.8 J/cm2 of UVA (365 nm). Samples were subjected to native PAGE at 200 V on a 3.5% TBE gel and analyzed using the Storage Phospor mode (390 BP/Red) on a Typhoon 9410 Variable Mode Imager (GE Healthcare).

To determine TFO binding in a cellular context, biotinylated oligonucleotides were transfected (5x10−5 M) into 1.5x106 COLO 320DM cells using Geneporter Transfection Reagent (Genlantis, San Diego, CA), and irradiated with 3.6 J/m2 UVA. Oligonucleotides covalently linked to genomic DNA were pulled-down using streptavidin-coated Dynabeads (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). The DNA was dissociated from Dynabeads, purified, radiolabeled, and subjected to native PAGE on an 8% gel at 225 V for 1.5 hours. The pull-down DNA was PCR amplified and analyzed on a 2% agarose gel. To verify the specificity of Myc2T binding, purified genomic DNA was digested with PvuII and RsaI, and pulled-down as described above, radiolabeled and digested with BbvCI. A 300-bp shift was measured following PAGE.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays

Oligonucleotides were transfected into COLO 320DM cells (1.5x106) using Geneporter transfection reagent. The “Enzymatic Chromatin IP Protocol” from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA) was used. The crosslinked DNA was pulled down with anti-NBS1 antibody (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO). The DNA was purified and PCR reactions were performed with primer sets 2 bp or 4 kb from the TFO-target site. Overall percent Myc2T from each corresponding input sample at the 2 bp primer set was compared to cells treated with TFOc among 3 different experiments and normalized to the 4 kb primer set. P values were calculated using a one-sample Student’s t-test against the TFOc mean value of 1.

In vivo GEM incorporation assays

COLO 320DM cells (1.5x106) were transfected using Geneporter transfection reagent with either Myc2T or TFOc at 1x10−5 M, and [3H]GEM at 1x10−7 M. After 20 hours of incubation at 37°C, DNA was isolated from the cells, digested with PvuII and separated on a 2% agarose gel. Two sections were gel purified from each lane: a region ~200–700 bp containing the TFO-targeted region; and a non-targeted region of ~5–30 kb. The amount of radioactivity in each sample was measured, and the 200–700 bp regions were normalized to background levels using the 5–30 kb regions.

Tumor xenograft studies in mice

Donor mice were inoculated subcutaneously (s.c.) with ~5x106 cultured COLO 320DM cells. Once the tumor mass reached ~1.5 cm3, donor mice were sacrificed, and tumors were removed for implantation into recipient mice for use in the studies. Tumor fragments (~30 mm3) were implanted s.c. near the left flank of recipient mice, and therapy was initiated 15 days later; treatments were given on a rotating dosing schedule, alternating between 3 times a week and 2 times a week until the end of the experiment. Mice were injected i.p. with PBS or GEM (18 mg/kg, 30 mg/kg, or 50 mg/kg) and i.t. with water or oligonucleotide (Myc2T or TFOc, 25 μL at 4x10−5 M). Tumor growth delay/regression was the evaluation end point; thus, tumor measurements were recorded on the initial day of treatment and at various times thereafter. The number of mice per group ranged from 3–7.

Statistical analysis of tumor growth

The significance of differences in tumor growth rates was tested between groups using (fixed-intercept, random-slope) mixture models. All measurements of each mouse within each particular group were linearized using a logarithmic scale. P values were determined using a 2-parameter (intercept and 1 regression line) against a 3-parameter (intercept and 2 regression lines) test. All statistical tests conducted were 2 sided with unequal variance.

RESULTS

TFOs bind specifically to their target sequences in vitro and in vivo

The specific TFO used in this study, Myc2T, has previously been shown to bind its target site in the promoter 2 region of the c-MYC gene [10,18,34]. To confirm binding in this study, radiolabeled Myc2T was incubated with increasing concentrations of target duplex DNA containing the c-MYC promoter target sequence, and analyzed by EMSAs. As shown in Figure 1B, Myc2T bound the target duplex resulting in a product that migrated more slowly on the gel than that of the duplex alone (indicative of triplex formation) when the duplex concentration reached 5x10−6 M. The scrambled control oligonucleotide, TFOc, did not appear to bind to the target duplex, but may have self-aggregated due to the high concentration, resulting in a product that migrated more slowly on the gel than that of the oligonucleotide alone, but faster than that of the duplex alone (Figure 1B).

To verify that the TFO bound its target site in the context of genomic DNA, TFO binding assays were performed on genomic DNA isolated from human COLO 320DM cells. Isolated genomic DNA was digested with restriction enzymes to isolate an ~860 bp fragment containing the Myc2T target site. Figure 1A shows a map of the TFO binding region including both the restriction enzyme sites and primer amplification areas of the human c-MYC gene. Psoralen-modified TFO (pMyc2T) and psoralen-modified control oligonucleotide (pTFOc) were radiolabeled and covalently crosslinked with the genomic DNA using ultraviolet A (UVA) irradiation. Incubation of genomic DNA with pTFOc followed by UVA irradiation yielded only non-specific bands corresponding to lengths slightly larger than 1 kb (Figure 1C). In contrast, incubation and crosslinking of pMyc2T to the genomic DNA produced a band ~800–900 bp (lane 4), the size expected with specific binding of pMyc2T to the target site.

To demonstrate binding of TFOs in vivo, TFOc and Myc2T modified with psoralen (on the 5’-end) and biotin (on the 3’-end) were used. The oligonucleotides were incubated with COLO 320DM cells with or without transfection reagent. Cells were then irradiated with UVA to crosslink the psoralen-modified oligonucleotides to the genomic DNA. The isolated DNA was then digested with PvuII and RsaI and isolated using streptavidin Dynabeads and radiolabeled. As shown in Figure 1D, lanes 2 (pMyc2T-bio) and 4 (pMyc2T-bio with Geneporter) had a band corresponding to the PvuII restriction enzyme cut sites at 800–900 bps. No discrete bands were detected in the lanes containing pTFOc-bio, suggesting that the control oligonucleotide did not bind to the c-MYC target site. As expected, the presence of a transfection reagent greatly enhanced binding of pMyc2T-bio to the genomic DNA, presumably due to increased uptake of the oligonucleotide into the cell. The binding of pMyc2T-bio was significantly higher than pTFOc across 3 separate experiments (Supplemental Table 1), suggesting specific binding in genomic DNA. When the DNA was digested with BbvCI restriction enzyme, there was an expected ~300 bp shift in the EMSA, illustrating the specificity of TFO binding (Supplemental Figure 1). Additionally, PCR amplification was performed on DNA following the pull-down reaction. PCR products were observed in the lanes containing pMyc2T-bio pull-down (Figure 1E). More DNA was present in the Geneporter sample as witnessed by the appearance of a larger amount of PCR product in lane 3 (Figure 1E). With the evidence presented here, we have demonstrated that the TFO binds genomic DNA in a sequence-specific fashion in cells, thereby illustrating the potential of triplex technology in in vivo applications.

Myc2T induces DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) and stimulates GEM incorporation in vivo

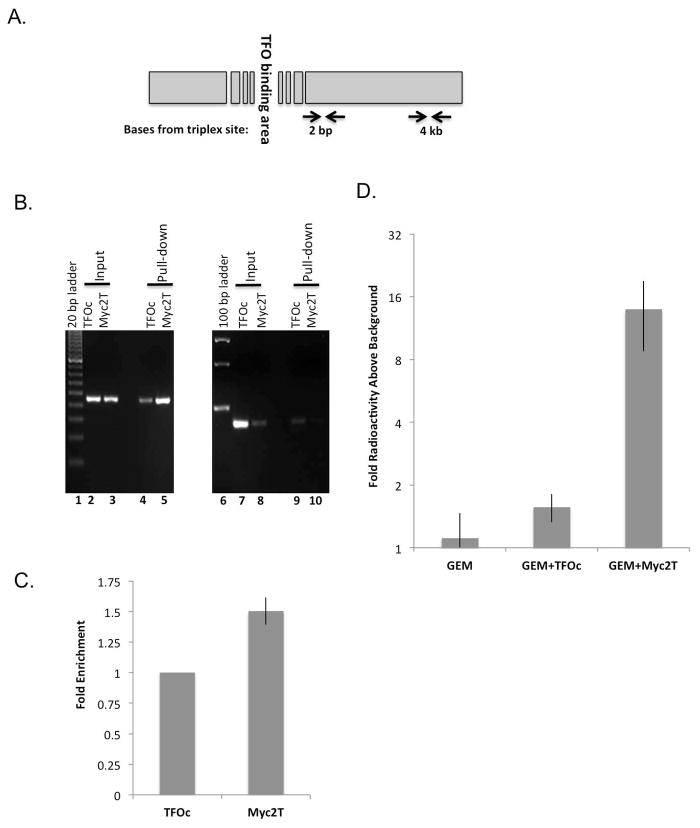

TFOs have been shown to induce mutagenesis, perhaps through the formation of DNA strand breaks during their processing [10,21,35]. NBS1, as part of the MRN complex, detects strand breaks and signals for their repair, and thus it can be used as a marker of DNA strand breaks in vivo [36]. Using a ChIP assay in extracts from TFO-transfected COLO 320DM cells, we demonstrate that the c-MYC targeting TFO induced site-specific DNA strand breaks, as evidenced by enrichment of NBS1 (by 1.5-fold, P<0.05, Figure 2C) bound to DNA adjacent (2 bp) to the triplex-target site in comparison to that in control TFOc-treated cells (Figures 2A and B). In contrast, when PCR primers were used to amplify a non-targeted region ~4 kb from the TFO-target site, there was no apparent difference in NBS1 binding in TFOc vs. Myc2T treated cells (Figure 2B, lanes 9 and 10).

Figure 2.

TFOs induce DNA damage and GEM incorporation at the TFO target site. (A) Schematic of the TFO-targeted region with two different primer sets, 2 bp and 4 kb from the triplex-forming site. (B) A representative agarose gel of a ChIP assay performed with extracts of TFO-treated COLO 320DM cells using primer binding sites 2 bp (lanes 2–5) and 4 kb (lanes 7–10) from the triplex-forming site. (C) Fold enrichment of NBS1 binding in the 2 bp primer set region adjacent to the Myc2T binding site of Myc2T-treated cells compared to TFOc-treated cells, normalized to that in the 4 kb primer set (*P<0.05 as calculated by one sample Student’s t-test against 1). (D) COLO 320DM cells were incubated with [3H]GEM and either Myc2T or control TFOc. The bar graph illustrates the fold increase of [3H]GEM of the TFO-targeted 200–700 bp fragment compared to a background sample of ~5 kb. (*P<0.05, Student’s t-test, unequal variance, for all samples against GEM + Myc2T, error bars indicate standard deviation).

To determine whether TFO-induced DNA damage would enhance GEM incorporation in genomic DNA, COLO 320DM cells were incubated with [3H]GEM and either control oligonucleotide (TFOc) or specific TFO (Myc2T). As shown in Figure 2D, [3H]GEM incorporation into the TFO targeted area was ~10-fold higher following treatment with GEM+Myc2T than with GEM+TFOc or GEM alone. Taken together, these data indicate that Myc2T treatment induced site-specific DNA breakage, with subsequent UDS resulting in forced incorporation of GEM into the TFO-targeted regions in genomic DNA.

TFOs potentiate the activity of GEM against a human colon tumor xenograft in mice

In preliminary studies designed to determine the efficacy of the TFO plus GEM combination therapy, mice bearing s.c. implanted COLO 320DM human colon carcinoma xenografts were treated with PBS (Control), Myc2T (25 μL/injection at 4x10−5 M) only, GEM (50 mg/kg) only, or GEM (50 mg/kg) plus Myc2T. While Myc2T used as a single agent did not produce a delay in tumor growth, the combination of GEM and Myc2T was more effective than GEM (50 mg/kg) when used alone (Supplemental Figure 2). In a second preliminary study (Supplemental Figure 3), we tested the impact of combining Myc2T with a lower dose of GEM (18 mg/kg). At this lower dose, GEM produced a slight delay in tumor growth, but the addition of Myc2T produced little if any effect. However, the combination of GEM at 50 mg/kg plus Myc2T again proved more effective in inhibiting tumor growth than either agent alone. Note: Mice were implanted with tumor fragments on day 0 and treatment was initiated 8 and 13 days later for the studies shown in Supplemental Figures 2 and 3, respectively.

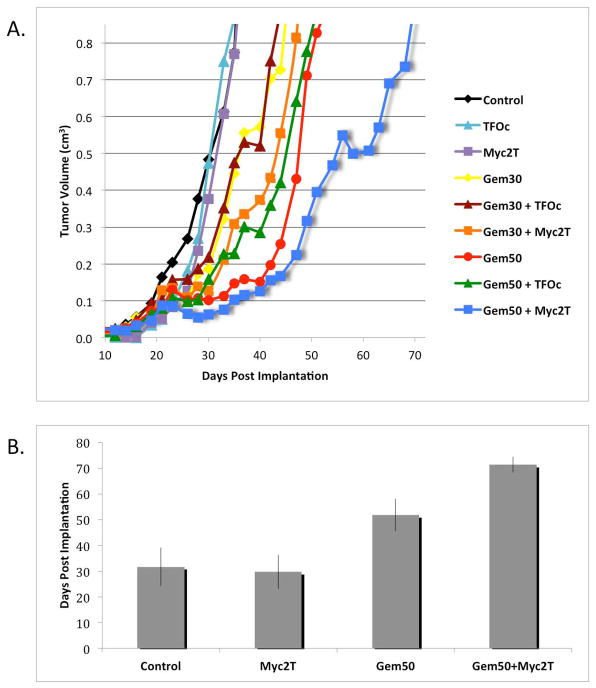

To confirm our preliminary results, athymic nude mice were implanted s.c. with fragments of the COLO 320DM human colon carcinoma and treatment was initiated 15 days post-tumor implantation. As shown in Figure 3A, neither Myc2T nor TFOc had an effect on tumor growth when administered as single agents. GEM at both 30 and 50 mg/kg inhibited tumor growth, with the higher dose producing greater inhibition. When the specific TFO for c-MYC (Myc2T) was used in combination with either dose of GEM, inhibition of tumor growth was greater than with that dose of GEM alone. Administering Myc2T with GEM (30 mg/kg) delayed tumor growth slightly compared to GEM (30 mg/kg) alone, but was less effective than GEM (50 mg/kg) alone. GEM (30 mg/kg) plus control oligonucleotide, TFOc, showed no greater inhibition of tumor growth than GEM (30 mg/kg) alone. However, when GEM (50 mg/kg) was administered in combination with Myc2T, tumor growth was inhibited significantly compared to GEM (50 mg/kg) alone (P<0.05). GEM (50 mg/kg) plus Myc2T similarly resulted in greater inhibition than GEM (50 mg/kg) plus TFOc. These results suggest that the specific TFO can be used to enhance the anti-tumor effects for two different doses of GEM.

Figure 3.

TFO enhanced antitumor activity of GEM against human colon carcinoma xenografts in mice. (A) Average tumor volume versus days post-surgical implantation. Mice were treated with PBS, Myc2T, TFOc, gemcitabine at 30 mg/kg of body weight (Gem30), at 50 mg/kg (Gem50), or combinations of oligonucleotides and gemcitabine. The mean tumor volume for each treatment group is plotted versus time. Gem50+Myc2T significantly inhibited tumor growth compared to Gem50 (P<0.05) and Gem50+TFOc (P<0.07). Each group consisted of at least 3 mice. (B) The average time for tumors to reach a volume of 0.85 cm3 is shown. Error bars indicate standard deviations from 3 independent experiments. The amount of time required for Gem50+Myc2T treated tumors to reach a volume of 0.85 cm3 was significantly longer than that of all other groups when analyzed by using the Student’s t-test, unequal variance, 2-sided (P<0.05).

Combining data from the two preliminary studies and the study depicted in Figure 3A, mean tumor volumes were calculated for the Control, Myc2T, GEM (50 mg/kg), and GEM (50 mg/kg) plus Myc2T treated animals. As depicted in Figure 3B, on average it took both the control and Myc2T only groups 30 days for the tumor volume to surpass 0.85 cm3 (the study end-point value). Treatment with GEM (50 mg/kg) alone delayed tumor growth with the mean tumor volume surpassing 0.85 cm3 at ~50 days. However, it took >70 days on average for the tumors in mice treated with the combination of GEM (50 mg/kg) plus Myc2T to reach the tumor volume endpoint. The differences in times for tumors to reach 0.85 cm3 in the GEM (50 mg/kg) plus Myc2T treated animals compared to that in the 3 other treatment groups were significant (P<0.05, Student’s t-test, 2-sided unequal variance).

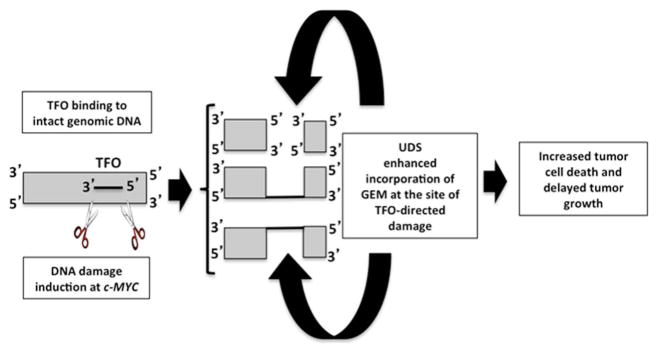

Taken together, our data demonstrate that TFOs can bind genomic DNA specifically, and induce TFO-targeted DNA damage, which facilitates the enhanced incorporation of a nucleoside antimetabolite into the damaged site, to ultimately potentiate the antimetabolite’s antitumor activity in a mouse model of human cancer (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Proposed mechanism for TFO-induced potentiation of GEM antitumor efficacy. The TFO binds its target sequence resulting in DNA strand breaks that stimulate repair synthesis, thereby facilitating incorporation of GEM into the TFO-targeted site, leading to enhanced GEM incorporation at the targeted oncogene and increased cell death.

DISCUSSION

Many cancer chemotherapeutic agents are most active against rapidly dividing cells. Importantly, these agents are also toxic to rapidly dividing normal cells, and thereby produce serious side effects for the patient. Clearly, a need exists to improve the specificity of these toxic agents for the cancer cells. On the other hand, the requirement for DNA synthesis for the susceptibility of tumors to many of these agents limits their effectiveness in treating solid tumors that contain a significant proportion of non-cycling or slowly-cycling cells. Thus, an additional need is to increase the fraction of susceptible cells in solid tumors to these agents. TFOs hold the promise to accomplish these needs.

In the current study, we have demonstrated specific TFO binding to the promoter region of the c-MYC gene in genomic DNA in vitro and also provide direct evidence of TFO binding specifically to its target site in the genome in vivo. Using a ChIP assay to detect binding of NBS1, a marker for DNA damage [36], we also show that TFO binding to its genomic target induces DNA strand breaks. Using extracts prepared from TFO-treated tumor cells, we found an increased amount of NBS1 adjacent to the TFO binding site (2 bp away), compared to a distant, non-targeted site 4 kb away. The induction of strand breaks likely stimulates repair processes and potentially directs cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Indeed, the cytotoxic/cytostatic properties of TFOs have been demonstrated using cell viability assays and/or tumor cell proliferation assays [10] likely via this mechanism.

We previously demonstrated increased GEM incorporation into plasmid DNA damaged by TFOs using human cell-free extracts [10]. Here, we were interested in demonstrating “proof of principle” of whether TFO-induced DNA damage would similarly stimulate incorporation of the nucleoside in vivo and in an animal model. For these studies we used a relevant human tumor cell line, COLO 320DM, which contains multiple copies of the c-MYC oncogene [37,38]. This cell line was established from surgical specimens of an invasive carcinoma of the colon that was resected from a 55-year-old Caucasian female [39] and has been used since 1985 by others searching for improved treatments for colon cancer in humans.

Following treatment of COLO 320DM cells with the c-MYC-specific TFO and [3H]GEM, we found substantially increased incorporation of the cytotoxic nucleoside analog into the TFO-targeted region. It follows from these data that TFO-induced DNA damage to oncogenes could be used in combination with DNA antimetabolites to potentiate their cytotoxicity; our previous cell culture studies demonstrated that combinations of c-MYC-targeting TFOs and GEM reduced human breast cancer cell survival and anchorage-independent growth more effectively than either agent when used alone [10]. Of primary significance, we have now substantially advanced this work, demonstrating the utility of the concept of TFO-targeting an oncogene to improve antitumor efficacy of an antimetabolite in a human colon cancer model in mice.

Addition of the c-MYC-specific TFO to the GEM treatment regimen clearly increased the effectiveness of GEM (administered at or near its MTD) without imposing additional toxicity for the mouse. However, since we were interested primarily in establishing “proof of principle” for the concept of combining an antimetabolite with a TFO, we did not go to extensive lengths to optimize the dosing schedule. Also, although formal toxicology evaluation was not performed, we did not observe any overt toxicity or body weight loss with these dose regimens and we did not attempt to increase the TFO level to a maximum tolerated dose. It is likely that even greater improvement in antitumor efficacy could be realized by optimizing dosing and scheduling.

Our rationale was to provide in vitro and cell-based mechanistic data as a justification for using animals in an efficacy study, assuming that the molecular mechanism(s) for the improved efficacy in the tumor setting would be essentially the same as demonstrated in cultured cells. None-the-less, physiological factors warranting further investigation may also play important roles in the enhanced antitumor efficacy of the TFO + GEM combination.

We have performed Western blot analysis of c-Myc and p21 (expression regulated by c-Myc [40]) proteins after 4, 24, and 48 hours incubation with the c-MYC targeting TFO, GEM, or the combination. No notable changes in either the c-Myc or p21 protein levels were observed (data not shown). This result is not inconsistent with our hypothesized mechanism underlying the potentiation of the antitumor activity of GEM by the c-MYC targeting TFO; that TFO-induced DNA damage facilitates increased incorporation of GEM during repair synthesis.

The results of our experiments showing dramatically increased incorporation of GEM into the TFO target site in cells incubated with the c-MYC-specific TFO indicate that increased incorporation of GEM into the DNA during repair induced by TFO binding increased the cytotoxicity of GEM for the tumor cell. This scenario is analogous to increased cytotoxicity brought about by exposure of the tumor cells to higher concentrations of GEM. In this case, the mechanism(s) of cytotoxicity induced by GEM when used in combination with the Myc2T TFO would remain the same as when GEM is used alone. We expect that this mechanism also operates in the xenograft model and is responsible for the potentiation of the antitumor activity of GEM by the Myc2T TFO. We suggest that the mechanism proposed in Figure 4 operates in cancer cells both in cell-based systems and in animals treated with the combination regimen of GEM and TFOs: 1) the TFO binds to its target sequence in genomic DNA in cells; 2) the unusual triplex structure is recognized as damage thereby attracting machinery that removes the triplex, resulting in DNA strand breaks; 3) repair synthesis facilitates incorporation of GEM into the repair patch; and 4) GEM incorporation leads to cell death. In this way, the TFO potentiates the antitumor activity of GEM.

Utilization of triplex technology should allow for more specific targeting of tumor cells that have amplification of a cancer-relevant gene than possible with non-targeted DNA damaging agents, and should substantially decrease host toxicity by sparing normal cells, while maximizing antitumor activity. We expect that this unique approach will not be limited to GEM, but can also be successfully applied to any cell-cycle dependent DNA antimetabolite. Moreover, the use of a specific oncogene-targeting TFO in combination with antimetabolite therapy should improve efficacy against any slow growing solid tumor, which has an amplified oncogene containing a triplex binding site. Notably, Wu et al. (2007) [41] developed a computer algorithm and searched the human genome for high-affinity TFO target sequences (TTS), finding that ~98% of known human genes have at least one such site in the promoter and/or transcribed regions of the gene and that ~86% of known human genes have at least one TTS that is unique to that gene. Thus, the potential of combining gene-specific TFOs with DNA-targeting drugs is enormous. We expect that TFO-directed DNA damage in conjunction with antimetabolite therapy will translate to more effective treatment strategies for solid tumors in humans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Aklank Jain for providing advice on the ChIP assays, and the other members of our laboratory for helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA097175 and CA093729 to K.M. Vasquez) and from the University Cancer Fund at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (to K.M. Vasquez).

Footnotes

The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2010. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rockwell S, Grindey GB. Effect of 2',2'-difluorodeoxycytidine on the viability and radiosensitivity of EMT6 cells in vitro. Oncol Res. 1992;4(4–5):151–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang P, Plunkett W. Fludarabine- and gemcitabine-induced apoptosis: incorporation of analogs into DNA is a critical event. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1995;36(3):181–188. doi: 10.1007/BF00685844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Futreal PA, Coin L, Marshall M, et al. A census of human cancer genes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(3):177–183. doi: 10.1038/nrc1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baselga J, Tripathy D, Mendelsohn J, et al. Phase II study of weekly intravenous trastuzumab (Herceptin) in patients with HER2/neu-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 1999;26(4 Suppl 12):78–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldenberg MM. Trastuzumab, a recombinant DNA-derived humanized monoclonal antibody, a novel agent for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Clin Ther. 1999;21(2):309–318. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(00)88288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shak S. Overview of the trastuzumab (Herceptin) anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody clinical program in HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. Herceptin Multinational Investigator Study Group. Semin Oncol. 1999;26(4 Suppl 12):71–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooney M, Czernuszewicz G, Postel EH, Flint SJ, Hogan ME. Site-specific oligonucleotide binding represses transcription of the human c-myc gene in vitro. Science. 1988;241(4864):456–459. doi: 10.1126/science.3293213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beal PA, Dervan PB. Second structural motif for recognition of DNA by oligonucleotide-directed triple-helix formation. Science. 1991;251(4999):1360–1363. doi: 10.1126/science.2003222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen LA, Finch RA, Booker AJ, Vasquez KM. Targeting oncogenes to improve breast cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2006;66(8):4089–4094. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Datta HJ, Chan PP, Vasquez KM, Gupta RC, Glazer PM. Triplex-induced recombination in human cell-free extracts. Dependence on XPA and HsRad51. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(21):18018–18023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogers FA, Vasquez KM, Egholm M, Glazer PM. Site-directed recombination via bifunctional PNA-DNA conjugates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(26):16695–16700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262556899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang G, Seidman MM, Glazer PM. Mutagenesis in mammalian cells induced by triple helix formation and transcription-coupled repair. Science. 1996;271:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim HG, Miller DM. Inhibition of in vitro transcription by a triplex-forming oligonucleotide targeted to human c-myc P2 promoter. Biochemistry. 1995;34(25):8165–8171. doi: 10.1021/bi00025a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Postel EH, Flint SJ, Kessler DJ, Hogan ME. Evidence that a triplex-forming oligodeoxyribonucleotide binds to the c-myc promoter in HeLa cells, thereby reducing c-myc mRNA levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(18):8227–8231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.18.8227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas TJ, Faaland CA, Gallo MA, Thomas T. Suppression of c-myc oncogene expression by a polyamine-complexed triplex forming oligonucleotide in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23(17):3594–3599. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.17.3594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim H-G, Reddoch JF, Mayfield C, et al. Inhibition of transcription of the human c-myc protooncogene by intermolecular triplex. Biochemistry. 1998;37(8):2299–2304. doi: 10.1021/bi9718191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Catapano CV, McGuffie EM, Pacheco D, Carbone GMR. Inhibition of gene expression and cell proliferation by triple helix-forming oligonucleotides directed to the c-myc gene. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5126–5138. doi: 10.1021/bi992185w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helm CW, Shrestha K, Thomas S, Shingleton HM, Miller DM. A unique c-myc-targeted triplex-forming oligonucleotide inhibits the growth of ovarian and cervical carcinomas in vitro. Gynecologic Oncology. 1993;49(3):339–343. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1993.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vasquez KM, Wang G, Havre PA, Glazer PM. Chromosomal mutations induced by triplex-forming oligonucleotides in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(4):1176–1181. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.4.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vasquez KM, Narayanan L, Glazer PM. Specific mutations induced by triplex-forming oligonucleotides in mice. Science. 2000;290(5491):530–533. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5491.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hertel LW, Kroin JS, Misner JW, Tustin JM. Synthesis of 2-deoxy-2,2-difluoro-D-ribose and 2-deoxy-2,2-difluoro-D-ribofuranosyl nucleotides. J Org Chem. 1988;53:2406–2409. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plunkett W, Huang P, Searcy CE, Gandhi V. Gemcitabine: preclinical pharmacology and mechanisms of action. Semin Oncol. 1996;23(5 Suppl 10):3–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crowther PJ, Cooper IA, Woodcock DM. Biology of cell killing by 1-beta-D-arabinofuranosylcytosine and its relevance to molecular mechanisms of cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 1985;45(9):4291–4300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merriman RL, Hertel LW, Schultz RM, et al. Comparison of the antitumor activity of gemcitabine and ara-C in a panel of human breast, colon, lung and pancreatic xenograft models. Invest New Drugs. 1996;14(3):243–247. doi: 10.1007/BF00194526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raguse JD, Gath HJ, Bier J, Riess H, Oettle H. Gemcitabine in the treatment of advanced head and neck cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2005;17(6):425–429. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rocha Lima CM, Urbanic JJ, Lal A, Kneuper-Hall R, Brunson CY, Green MR. Beyond pancreatic cancer: irinotecan and gemcitabine in solid tumors and hematologic malignancies. Semin Oncol. 2001;28(3 Suppl 10):34–43. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2001.22534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Moorsel CJ, Pinedo HM, Veerman G, et al. Mechanisms of synergism between cisplatin and gemcitabine in ovarian and non-small-cell lung cancer cell lines. Br J Cancer. 1999;80(7):981–990. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robertson LE, Kantarjian H, O'Brien S, et al. Cisplatin, fludarabine, and ara-C (PFA): A regimen for advanced fludarabine-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1993;12:308. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robertson LE, O'Brien S, Kantarjian H, et al. Fludarabine plus doxorubicin in previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 1995;9(6):943–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keating MJ, O'Brien S, McLaughlin P, Kantarjian H, Cabanillas F. Fludarabine in combinations in the management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and low grade lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 1996;7:34. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLaughlin P, Hagemeister FB, Romaguera JE, et al. Fludarabine, mitoxantrone, and dexamethasone: an effective new regimen for indolent lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(4):1262–1268. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.4.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zendegui JG, Vasquez KM, Tinsley JH, Kessler DJ, Hogan ME. In vivo stability and kinetics of absorption and disposition of 3' phosphopropyl amine oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Research. 1992;20(2):307–314. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.2.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim HK, Kim JM, Kim SK, Rodger A, Norden B. Interactions of intercalative and minor groove binding ligands with triplex poly(dA).[poly(dT)]2 and with duplex poly(dA). poly(dT) and poly[d(A-T)]2 studied by CD, LD, and normal absorption. Biochemistry. 1996;35(4):1187–1194. doi: 10.1021/bi951913m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mukherjee A, Vasquez KM. Triplex technology in studies of DNA damage, DNA repair, and mutagenesis. Biochimie. 2011;93(8):1197–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berkovich E, Monnat RJ, Jr, Kastan MB. Roles of ATM and NBS1 in chromatin structure modulation and DNA double-strand break repair. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(6):683–690. doi: 10.1038/ncb1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harlow SP, Stewart CC. Quantitation of c-myc gene amplification by a competitive PCR assay system. PCR Methods Appl. 1993;3(3):163–168. doi: 10.1101/gr.3.3.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alitalo K, Schwab M, Lin CC, Varmus HE, Bishop JM. Homogeneously staining chromosomal regions contain amplified copies of an abundantly expressed cellular oncogene (c-myc) in malignant neuroendocrine cells from a human colon carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80(6):1707–1711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.6.1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quinn LA, Moore GE, Morgan RT, Woods LK. Cell lines from human colon carcinoma with unusual cell products, double minutes, and homogeneously staining regions. Cancer Res. 1979;39(12):4914–4924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gartel AL, Ye X, Goufman E, et al. Myc represses the p21(WAF1/CIP1) promoter and interacts with Sp1/Sp3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(8):4510–4515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081074898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu Q, Gaddis SS, MacLeod MC, et al. High-affinity triplex-forming oligonucleotide target sequences in mammalian genomes. Mol Carcinog. 2007;46(1):15–23. doi: 10.1002/mc.20261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.