Abstract

Objective

To determine the prevalence of obesity-related behaviors and attitudes in children’s movies.

Design and Methods

We performed a mixed-methods study of the top-grossing G- and PG-rated movies, 2006–2010 (4 per year). For each 10-minute movie segment the following were assessed: 1) prevalence of key nutrition and physical activity behaviors corresponding to the American Academy of Pediatrics obesity prevention recommendations for families; 2) prevalence of weight stigma; 3) assessment as healthy, unhealthy, or neutral; 3) free-text interpretations of stigma.

Results

Agreement between coders was greater than 85% (Cohen’s kappa=0.7), good for binary responses. Segments with food depicted: exaggerated portion size (26%); unhealthy snacks (51%); sugar-sweetened beverages (19%). Screen time was also prevalent (40% of movies showed television; 35% computer; 20% video games). Unhealthy segments outnumbered healthy segments 2:1. Most (70%) of the movies included weight-related stigmatizing content (e.g. “That fat butt! Flabby arms! And this ridiculous belly!”).

Conclusions

These popular children’s movies had significant “obesogenic” content, and most contained weight-based stigma. They present a mixed message to children: promoting unhealthy behaviors while stigmatizing the behaviors’ possible effects. Further research is needed to determine the effects of such messages on children.

Keywords: Childhood obesity, children, stigma, weight-related teasing, movies

Introduction

Childhood obesity is an ever increasing national concern, and rates of obesity in children have more than tripled in the past 30 years. Pediatric overweight prevalence is at 32%,1 and it remains an important public health problem with significant co-morbidities and predictors of adult chronic disease.2 There are likely many reasons why the obesity rate has increased, including changes in availability, cost, and preferences for food and less time spent in physical activity. However, media use likely plays a role as well.

It has been clearly demonstrated that children who watch more television have an increased risk of being overweight,3 a relationship that may extend to other forms of screen time such as movies, computers, and handheld electronic devices. Most studies have attributed the relationship between screen time and obesity to the sedentary nature of watching television or movies. However, studies have also shown increased caloric intake and consumption of food with poor nutritional value associated with television,4–6 suggesting that the mechanism linking media exposure and obesity may go beyond the physical aspects of screen time. Furthermore, the socioeconomic status (SES)-body mass index (BMI) relationship may be moderated by exposure to media,7 whose audience tends to be disproportionately lower-SES, African American, and Hispanic. One possible mechanism may be product placement. One study found that product placement in over 200 movies from 1995–2005 was disproportionate for obesogenic items.8 Another found that 98% of food products advertised to children on television are high in calories, sodium, or fat. 9 There is less literature on content than advertising, although a few studies have found high rates of unhealthy foods in children’s television programming.10–12

The fact that DVDs are available for inexpensive purchase or rental, and movies can be streamed onto multiple different devices, contributes to children’s easy access to many movies and ability to view them repeatedly. On an average day in the United States, 42% of 3–4 year olds watched videos or DVDs for 87 minutes.13 Exposure to movies and other screen media is greater among minorities, particularly black children. Whereas on average, white children ages 8–18 years watch movies in the theater and DVDs at home for 62 minutes a day, black children average 108 minutes, and Hispanic children 73 minutes.14, 15

The content of movies affects children’s health beliefs and behaviors. Movie and other media exposure among young people has been associated with a range of negative outcomes, including alcohol use,16 violence,17 and sexual behavior.18 Watching movies featuring tobacco use is associated with teenage smoking.19 Adolescents who had the highest exposure to smoking in movies were nearly three times as likely to initiate smoking as those with the lowest exposure, and exposure to movie smoking is the primary independent risk factor for initiating smoking.20 Given the successes of having some movie studios implement guidelines to limit smoking depiction in movies,21 such research is even more important.

In a study on injury-prevention practices in children’s movies, the authors recommended that, when counseling families, pediatricians consider the potential impact of behaviors depicted in films.22 In an editorial in Pediatrics, Strasburger called pediatricians “clueless” on media effects and called for examining the effects of media exposure on risk behaviors among children and adolescents.23 In this study we follow these calls, examining messages in children's movies about obesity, overweight, and stigma. The primary objective of this study was to assess the presence of key obesity-related messages, behaviors, and attitudes in recent, top grossing G- and PG-rated movies.

Methods and procedures

Sample

We performed a mixed-methods study for 20 movies: the four top-grossing G or PG movies released each year from 2006 to 2010 inclusive. We chose the five most recent years for which data were available at the time of the study in order to remain current since cultural attitudes could change quickly, and we chose four movies per year in order to balance breadth of content with cost of coding. Top-grossing movies were determined using Box Office Mojo®, (http://www.boxofficemojo.com) a website that tracks US box-office revenue and has been used in other studies on portrayals of health behaviors,24 as well as marketing science.25 Because of varying time spans between theater release and home video release and because box-office success has been shown to relate to all downstream contracts (such as DVDs, network, satellite, and internet sales),26 we used box-office revenue to determine which movies we would include. The movies were: 2006: Night at the Museum, Cars, Happy Feet, Ice Age: The Meltdown; 2007: Shrek the Third, National Treasure, Alvin and the Chipmunks, Ratatouille; 2008: WALL-E, Kung Fu Panda, Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa, Horton Hears a Who!; 2009: Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, Up, Alvin and the Chipmunks: The Squeakuel, Monsters vs. Aliens; 2010: Toy Story 3, Alice in Wonderland, Despicable Me, Shrek Forever After.

Variables Coded

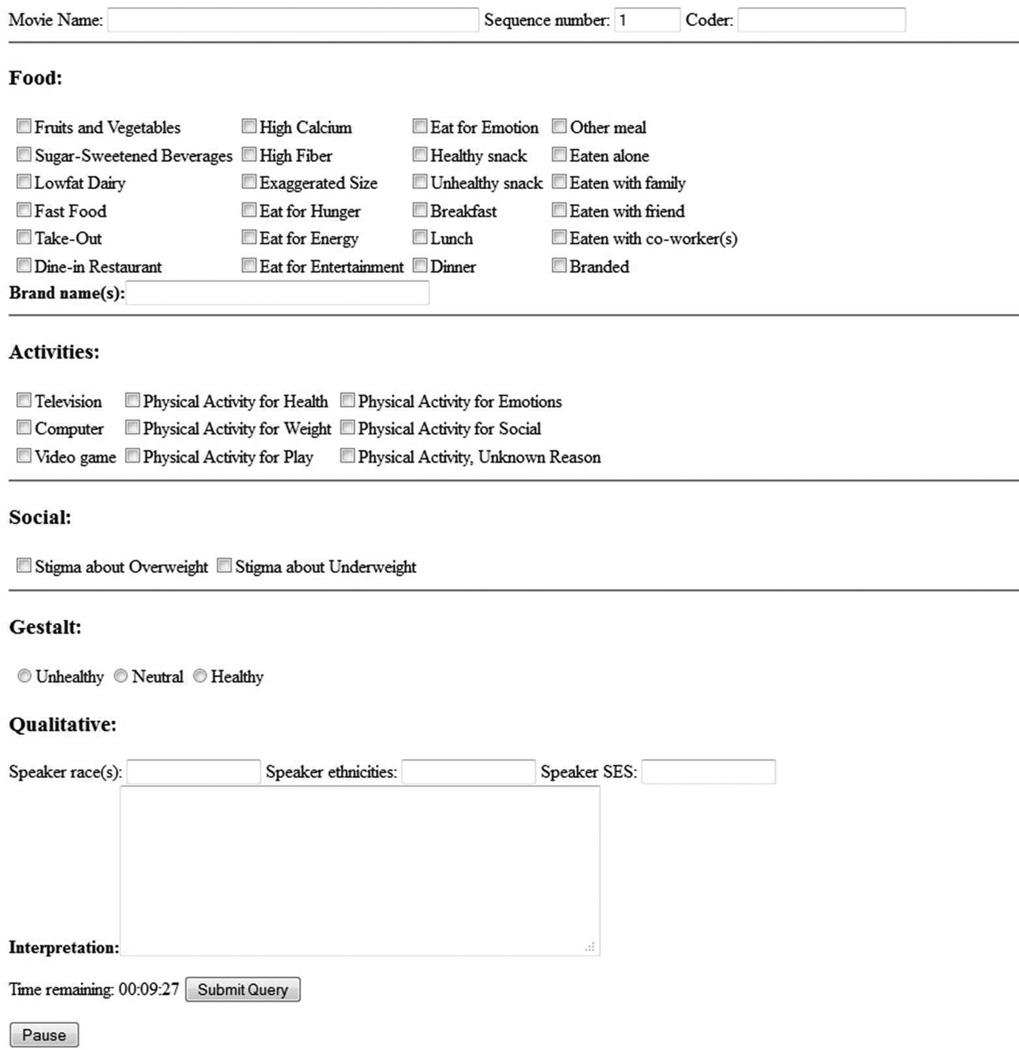

We developed a list of healthy behaviors based on the AAP’s “Prevention and Treatment of Childhood Overweight and Obesity: What Families Can Do.”27 These suggest eating fruits and vegetables; getting physical activity; limiting screen-time, fast foods, and sugar sweetened drinks; and eating together as a family. To develop a coding scheme applying those recommendations, all authors viewed one children’s movie from outside the study time period to devise a methodology and coding sheet and then confirmed the viability of the coding using two additional movies outside the time period. This resulted in a coding scheme with 35 observable behaviors related to food and physical activity, including both behaviors based on the AAP recommendations and additional items, such as stigma related to weight (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Screen image of the data-capture form.

Unit of Analysis

Each film was broken into 10-minute coding segments, and each segment was evaluated for each of the behaviors similar to other previously used health behavior coding schemes.22 We chose to use a defined time for segments, rather than “scenes,” because we determined during development of the coding sheet that scene was often difficult to ascertain reliably, and we confirmed this with a film-studies scholar at our university (personal communication). The electronic tracking of 10-minute segments provided a more reliable method of ensuring all coders were examining the same discrete portions of the movie.

Coding Tool

We created an online coding tool to systematize the coding process (Figure 1). The tool, written in Perl and Java and hosted on a secure server, allowed each coder to view a movie with a coding device—a laptop computer or internet tablet—and, in real time, document the presence or absence of each of the observable behaviors as the coding tool tracked 10-minute coding segments. The tool also prompted coders to evaluate each segment overall in terms of whether it was generally “healthy,” “unhealthy,” or “neutral,” in accordance with AAP guidelines, and provided space to record quotes or other open-ended comments for later qualitative analysis. Coders electronically checked the boxes for any of the behaviors that appeared during the 10-minute period and recorded any relevant qualitative information. Data were automatically stored in a secured PostgreSQL database server and exported as necessary to Stata for analysis.

Analysis

We focused on nine behaviors from the coded items that are supported by the literature and that our study team (including experts in health policy, pediatrics, childhood obesity, and sociology) believed form key elements of obesogenic lifestyles: unhealthy snacks, physical activity (we did not include involuntary activity, such as a character running to escape an enemy), screen time (television, computer, and video games), fast food, exaggerated portion size (assessed as an emphasis on the size of the food’s portion) , and sugar-sweetened beverages. Additionally, we examined stigma toward both underweight and overweight. Although stigma is a subjective measure, we coded based on interactions between characters (such as a stigmatizing statement) and presentation in the film (such as placing obese characters in stereotypical roles). This is consistent with commonly-accepted definitions of stigma.28

Two raters coded each movie using the same electronically-timed 10-minute segments. Stata 12.0 (College Station, TX) was used to calculate Cohen’s kappa test of agreement between coders. The twenty movies contained a total of 193 10-minute segments. Agreement for each construct by segment ranged from 75% to 99%, except for exaggerated size, which had agreement of only 54%. Cohen’s kappa for all constructs at the movie level was 0.7 for 85% agreement (p<0.0001). We considered a segment to demonstrate a particular construct if either rater noted it.

Results

Unhealthy eating behaviors were prevalent in the movies in our sample (Table 1). Most movies portrayed sugar-sweetened beverages (55%), exaggerated portion sizes (60%), and unhealthy snacks (75%). Fast food (15%) and branded foods (25%) were less prevalent. When examining only those segments that contained eating-related behaviors (n=102), 51% portrayed unhealthy snacks, 26% exaggerated size, and 19% sugar-sweetened beverages (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Number and percent of segments (n=193) and movies (n=20) depicting the listed behavior.

| Segments | % Segments | Movies | % Movies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=193 | N=20 | |||

| Eating | ||||

| Sugar-sweetened Beverages | 19 | 9.8 | 11 | 55 |

| Fast Food | 4 | 2.1 | 3 | 15 |

| Branded Food | 13 | 6.7 | 5 | 25 |

| Exaggerated Size | 26 | 13.5 | 12 | 60 |

| Unhealthy Snacks | 52 | 26.9 | 15 | 75 |

| Physical Activity | ||||

| TV | 24 | 12.4 | 8 | 40 |

| Computer | 16 | 8.3 | 7 | 35 |

| Video Game | 11 | 5.7 | 4 | 20 |

| Physical Activity (Any voluntary reason) | 98 | 50.8 | 19 | 95 |

| Stigma | ||||

| Stigma Overweight | 45 | 23.3 | 14 | 70 |

| Stigma Underweight | 5 | 2.6 | 4 | 20 |

| Stigma Combined | 48 | 24.9 | 16 | 80 |

TABLE 2.

Percent of segments (n=193) depicting the listed behavior, within each behavior category.

| Segments | % Segments | |

|---|---|---|

| Any Eating Behavior | ||

| Sugar-sweetened Beverages | 19 | 18.6 |

| Fast Food | 4 | 3.9 |

| Branded Food | 13 | 12.8 |

| Exaggerated Size | 26 | 25.5 |

| Unhealthy Snacks | 52 | 51.0 |

| Any Activity-Related Behavior | ||

| TV | 24 | 21.4 |

| Computer | 16 | 14.3 |

| Video Game | 11 | 9.8 |

| Physical Activity (Any voluntary reason) | 98 | 87.5 |

| Stigma | n=48 | 24.9 |

| Stigma Overweight | 45 | 93.8 |

| Stigma Underweight | 5 | 10.4 |

Physical activity was common throughout the movies, portrayed in 95% of movies and 51% of segments (Table 1). Sedentary activity was also commonly portrayed by characters in movies, including TV (40%), computer (35%), and video games (20%). Among segments that show any activity- or sedentary-related behaviors (n=112), 21% portrayed television watching, 14% showed computer use, and 10% showed video games (Table 2).

Stigma about body size was also extremely prevalent: 70% of the movies (n=14) included at least one instance of stigma against overweight people, while 20% (n=4) demonstrated stigma about underweight. Overall, one-quarter (24.9%) of the 10-minute segments included weight-related stigma, indicating common use of stigmatizing comments or images. When stigma was present (n=48), it was almost always related to overweight (94%) rather than underweight (Table 2).

When looking at the overall “gestalt” of whether each segment was “unhealthy” or “healthy”, more segments were considered unhealthy (33.2%) than healthy (17.6%). However, every movie included at least one neutral scene, 95% included at least one unhealthy scene, and 90% included at least one healthy scene.

Table 3 presents examples of qualitative observations regarding the stigmatizing comments and behaviors made by coders during the films. For example, in Alvin and the Chipmunks: The Squeakquelone coder wrote: “Ryan Edwards, a popular athlete at the high school the chipmunks attend, remarks to one of the chipmunks: ‘It’s the fatty ratty. That rat has serious junk in the trunk.’ In the next scene, the same chipmunk is concerned about being too overweight.”

TABLE 3.

Examples of free-text comments by coders.

| Movie | Comment while coding |

|---|---|

| WALL-E | Humans are so obese they are incapable of walking and spend all day lounging on hover chairs and drinking giant beverages. |

| Kung Fu Panda | Master Shifu, a Kung Fu master talking to Po, a large panda, about how to be successful in martial arts: “One must first master the highest level of Kung Fu and that is clearly impossible if that one is someone like you… That fat butt! Flabby arms! And this ridiculous belly!” |

| Shrek the Third | When Puss in Boots and Donkey magically trade places and Puss in Boots ends up in Donkey's body, he immediately dislikes what he sees and exclaims, “You should think about going on a diet!” |

| Harry Potter and the Half Blood Prince | At a group dinner celebrating the students' successes, the least impressive guest is the one who most quickly shovels ice cream into his mouth. |

| Ratatouille | Alfred Linguine, who works in a fancy French restaurant, addresses a food critic, Anton Ego: “You're too thin for someone who likes food.” Anton Ego: “I don't like food, I love it. If I don't love it, I don't swallow.” |

| Horton Hears a Who | Horton, an elephant, prepares to cross a rickety bridge and tells himself to “Think light!” |

| Alvin and the Chipmunks: The Squeakuel | Ryan Edwards, a popular athlete at the high school the chipmunks attend, remarks to one of the chipmunks: “It's the fatty ratty. That rat has serious junk in the trunk.” In the next scene, the same chipmunk is concerned about being too overweight. |

| Happy Feet | Mumble, a penguin trying hard to impress a new group of fellow penguin friends, shouts “See you fatty!” at a leopard seal. The friends laugh with great amusement. |

| Ice Age 2 | Ellie, a woolly mammoth raised with possums, explains her childhood, “You know, deep down, I knew I was different. I was a little bigger than the other possum kids. Okay, a lot bigger. Oh! Now I understand why the possum boys didn't find me appealing.” |

| Alice in Wonderland | The Queen of Hearts, looking for Tweedle-Dee and Tweedle-Dum, “Where are my fat boys?… I love my fat boys.” |

Discussion

Obesogenic content was present in the majority of popular children’s movies, and commonly recurred throughout the movies. Indeed, scenes where the overall content was unhealthy outnumbered scenes that primarily had healthy messages by a nearly 2:1 ratio. This prevalence of “obesogenic” behaviors in the content has the potential to influence children in harmful ways.

Our results are in line with the limited previous research on obesity-related messages in television. Although most television research has focused on advertising,29 some work has shown that unhealthy food messages are prevalent in children’s television shows.10–12 Although children with greater exposure to television have more stigmatizing beliefs about obesity,30 there is limited research examining the amount of stigmatizing content of television shows.

Perhaps more surprising and concerning than the obesogenic content of the movies was the prevalence of stigmatizing content towards overweight/obese characters or the possibility of becoming overweight. Over 90% of all weight stigmatizing messages was obesity-focused, as opposed to stigmatizing for being too thin. Many schools and parents discourage bullying and teach that judging and teasing people who are different is wrong, yet movies often contain messages tacitly encouraging these behaviors toward overweight and obese people. Since children who are bullied and teased are more likely to have unhealthy weight control behaviors31 and caloric consumption actually increases among people exposed to weight stigma,32 encouraging stigma about weight may perpetuate a dangerous cycle in which stigmatized children cope with the stigma using unhealthy eating behaviors, thus increasing their risk of overweight and perpetuating the cycle. Previous work has shown that greater media exposure among children is associated with greater obesity-related stigmatizing attitudes.30 Other work has investigated a particular type of media content and stigma (such as cartoons33) or investigating stigma in mostly adult obesity-themed movies,34 yet our demonstration of the prevalence of stigmatizing messages alongside obesogenic messages among top-grossing children’s movies is an important and new part of understanding this puzzle. Further research is necessary to determine if this mixed message may be driven, in part, through stigmatizing messages in popular culture.

These child- and family-targeted movies seem to present a complicated picture. They depict unhealthy choices (e.g., nutrient-poor, calorie-dense food, prevalent sedentary activity) as the norm, while simultaneously mocking the effects that such behaviors likely yield. Unlike films featuring smoking and violence, which tend to glamorize the behavior in question, the presentation of obesity is condemning while the presentation of unhealthy food and exercise choices is often positive. This creates a double-edged sword: few healthy eating behaviors are modeled, yet once someone actually becomes overweight, he or she becomes the subject of ridicule. This picture is even further complicated by the frequent portrayal of physical activity. While screen time is also high in movies, just over half of the segments do show a character engaged in some type of physical activity, for any voluntary reason (i.e. being chased does not count). This healthy demonstration of physical activity stands in conflict with the frequent depiction of both sedentary behaviors and unhealthy eating patterns. This discordant presentation may confuse the messages children actually receive about food, exercise, and weight, and further research is needed to determine how children interpret this complex presentation.

The obesity-related messages presented in movies almost certainly impact children’s behaviors. We know that viewed content can influence behavior at other times; that is the essence of advertising and product placement in television programs and movies. Given what has been observed between movie content and related behavior with tobacco use,19 violence,17 and sexual activity,18 messaging within movies could influence healthy nutrition and activity in children. Because content may influence behavior of children well after the movie ends, it may also explain part of the relationship between screen time and obesity. Consistent with previous research demonstrating that cereal with popular TV and movie characters on the box was rated as tasting better than the same cereal without those images,35 children's movies might particularly influence their preferences and behaviors, both consciously and unconsciously.

One limitation of this research was that we coded only 20 movies. Since these were the 20 films representing the four top-grossing films each year for the last five years, they likely reflect what many children are watching today, but by no means encompass all movies children view, particularly once the films are out of theaters and viewed via DVD or streaming video. Future research could include a larger number of movies, potentially expanding the number of years covered and examining whether the themes discovered here change over time. Another significant limitation is the use of an unvalidated coding measure. However, we used an approach similar to other published work,22 and our coding showed good agreement and face validity. No existing validated measure allowed us to match content to AAP recommendations or other obesogenic criteria. Although studies of tobacco use in media have used counts and timed exposure, assessing obesogenic behaviors,36 which are more variable, is less amenable to such specific timing. A related limitation is that only two coders rated each movie. Having more coders would have helped with some subjective categories, such as exaggerated portion size, which can be difficult to determine. Future research in this area would likely benefit from having more coders or, at least, a third “tie-breaker” coder for the subjective measures or any time the original coders disagreed. With the exception of exaggerated size, though, the two coders’ agreement exceeded 75% for each construct.

Another potential limitation is the inclusion of both animated and live-action movies. Many of the animated films feature animal protagonists, complicating the presentation of what constitutes “healthy” eating behaviors. Though the animals are typically thoroughly anthropomorphized, it is hard to know how much a hippopotamus, for example, really should eat. The animals also complicate our understanding of stigmatizing comments, since it is usually animals who are naturally larger (pandas, hippos, mammoths, etc.) who are mocked for their size. Young movie viewers may make a distinction between human and animal characters when learning from these films, although animals' body shape and size are often used to signal human characteristics such as sloth or obesity in children's books.37 The relatively small number of movies coded of each type precludes our analyzing whether live action movies differed from animated in terms of their obesogenic content. Future research should also examine how context affects young viewers’ understanding of healthy eating and activity patterns. In certain circumstances, eating large quantities may be warranted, such as after vigorous exercise or if the character had been food deprived or…if the character is an elephant! Our current study did not assess these contextual issues, which would be interesting for future research.

This research also did not assess how these messages are received by children, so we cannot speak to the effect of such obesogenic content on children’s eating or activity patterns or thoughts about or reactions to stigma. Future research should investigate children’s interpretations and the relationship between children’s eating and activity and their watching of movies with high obesogenic and stigmatizing content.

The Disney Corporation has recently promised to ban junk food ads from their television network. If further research suggests that the effect of children’s movies’ obesogenic content is a negative one on children’s eating or activity behaviors, policy responses such as corporate responsibility (as has occurred to some extent for smoking in movies38), content regulation, or media literacy interventions may be warranted. The prevalence of stigma in these movies underscores the importance of adopting the Rudd Center’s Guidelines for the Portrayal of Obese Persons in the Media,39 which encourage “respecting diversity and avoiding stereotypes,” using appropriate “language and terminology,” having “balanced and accurate coverage of obesity,” and using “appropriate pictures and images of obese persons.”

In this first ever study of the obesity-related eating and activity patterns portrayed in major motion pictures intended for a family audience, unhealthy segments outnumbered healthy ones nearly 2:1 when compared to recommended AAP recommendations for families. Also, 75% of the films contained stigmatizing content about weight status. Rates of exposure to stigmatizing as well as obesogenic content in these G- and PG- rated films even exceeded the prevalence of smoking in movies, and furthermore, on-screen smoking averages only 1–2 minutes per film, likely far less than the behaviors reviewed here.21 While, unlike smoking, we do not know the effect of such obesogenic or stigma-related content on children or their families, these striking results in the face of an obesity epidemic call for further research into how children interpret these movies and whether there are unhealthy ramifications. Additional research should also evaluate whether any effects differ by race/ethnicity. Differences could occur due to the race/ethnicity of characters displaying obesogenic or stigmatizing behavior, as in research on smoking in movies,40 and/or because exposure to movies is greater among minorities, particularly black children.14, 15 Future directions of this work would need to confirm these findings with a larger group of movies and to determine if there are health consequences to these portrayals. If there are consequences to such eating, sedentary, and stigmatizing behaviors in movies, it is possible that media literacy could help children recognize the mixed messages movies send and be aware of modeling their own behaviors after their favorite characters.

What is already known about this subject

Movie watching influences youth health behaviors like smoking and alcohol consumption.

Despite the high rate of childhood obesity, no studies have examined dietary or activity practices or stigma about obesity in children’s movies.

What this study adds

Recent top-grossing G and PG movies feature obesogenic dietary and activity practices.

Significant obesity-related stigma exists in children’s movies.

Children’s movies, then, offer a discordant presentation about food, exercise, and weigh status, glamorizing eating and activity behaviors yet condemning obesity itself.

Acknowledgements

MS originally had the idea to conduct the study, and MS and EP wrote the grant that funded part of the study. All authors participated in the design of the study. AP designed the coding tool and data collection apparatus. ET, AS, DO, EP, and AP participated in data collection. AS, AP, and EP analyzed data. All authors were involved in writing the paper and had final approval of the submitted version. We would like to acknowledge the Scientific Collaboration of Overweight and Obesity Prevention and Treatment, Stephanie Hasty, and Megan Campbell for their help throughout this project. This project was supported by the Children’s Promise Research grant. Dr. Skinner is supported by an NIH BIRCWH award (K12-HD01441). Drs. E. Perrin, Skinner, and Odulana were supported by a CTSA Grant to UNC (UL1RR025747).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no competing interests relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307:483–490. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dietz WH. Health consequences of obesity in youth: childhood predictors of adult disease. Pediatrics. 1998;101:518–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gortmaker SL, Must A, Sobol AM, Peterson K, Colditz GA, Dietz WH. Television viewing as a cause of increasing obesity among children in the United States, 1986–1990. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150:356–362. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290022003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coon KA, Tucker KL. Television and children's consumption patterns. A review of the literature. Minerva Pediatr. 2002;54:423–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyland EJ, Harrold JA, Dovey TM, et al. Food Choice and Overconsumption: Effect of a Premium Sports Celebrity Endorser. The Journal of pediatrics. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sisson SB, Broyles ST, Robledo C, Boeckman L, Leyva M, et al. Television viewing and variations in energy intake in adults and children in the USA. Public health nutrition. 2012;15:609–617. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011002916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morgenstern M, Sargent JD, Hanewinkel R, et al. Relation between socioeconomic status and body mass index: evidence of an indirect path via television use. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:731–738. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sutherland LA, MacKenzie T, Purvis LA, Dalton M, et al. Prevalence of food and beverage brands in movies, 1996–2005. Pediatrics. 2010;125:468–474. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powell LM, Szczypka G, Chaloupka FJ, Braunschweig CL. Nutritional content of television food advertisements seen by children and adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics. 2007;120:576–583. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radnitz C, Byrne S, Goldman R, Sparks M, Gantshar M, Tung K, et al. Food cues in children's television programs. Appetite. 2009;52:230–233. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson LM, Anderson J, et al. Barney and breakfast: messages about food and eating in preschool television shows and how they may impact the development of eating behaviours in children. Early Child Development and Care. 2009;180:1323–1336. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byrd-Bredbenner C, Finckenor M, Grasso D, et al. Health Related Content in Prime-Time Television Programming. Journal of Health Communication. 2003;8:329–341. doi: 10.1080/10810730305721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vandewater EA, Rideout VJ, Wartella EA, Huang X, Lee JH, Shim MS. Digital childhood: electronic media and technology use among infants, toddlers, and preschoolers. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1006–e1015. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rideout V, Foehr U, Roberts D, et al. Generation M2: Media in the Lives of 18- to 18-Year- Olds. Menlo Park, California: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Common Sense Media. Zero to Eight: Children's Media Use in America. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanewinkel R, Sargent JD, Poelen EA, et al. Alcohol consumption in movies and adolescent binge drinking in 6 European countries. Pediatrics. 2012;129:709–720. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson CA, Berkowitz L, Donnerstein E, et al. The influence of media violence on youth. Psychological science in the public interest. 2003;4:81–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-1006.2003.pspi_1433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown JD, L'Engle KL, Pardun CJ, Guo G, Kenneavy K, Jackson C, et al. Sexy media matter: exposure to sexual content in music, movies, television, and magazines predicts black and white adolescents' sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1018–1027. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Titus-Ernstoff L, Dalton MA, Adachi-Mejia AM, Longacre MR, Beach ML. Longitudinal study of viewing smoking in movies and initiation of smoking by children. Pediatrics. 2008;121:15–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sargent JD, Beach ML, Adachi-Mejia AM, et al. Exposure to movie smoking: its relation to smoking initiation among US adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1183–1191. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heatherton TF, Sargent JD. Does Watching Smoking in Movies Promote Teenage Smoking? Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18:63–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01610.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tongren JE, Sites A, Zwicker K, Pelletier A, et al. Injury-Prevention Practices as Depicted in G- and PG-Rated Movies, 2003–2007. Pediatrics. 2010;125:290–294. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strasburger VC. Go ahead punk, make my day: it's time for pediatricians to take action against media violence. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1398–e1399. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stern S, Morr L. Portrayals of teen smoking, drinking, and drug use in recent popular movies. J Health Commun. 2013;18:179–191. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.688251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chintagunta PK, Gopinath S, Venkataraman S. The effects of online user reviews on movie box office performance: Accounting for sequential rollout and aggregation across local markets. Marketing Science. 2010;29:944–957. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young SM, Gong JJ, Van der Stede WA, Sandino T, Du F. The business of selling movies. Strategic finance. 2008;89:35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Academy of Pediatrics. [Accessed June 21 2013];Prevention and Treatment of Childhood Overweight and Obesity: What Families Can Do. 2013 http://www2.aap.org/obesity/families.html.

- 28. [Accessed November 29, 2012];Weight Bias and Stigma. 2012 http://www.yaleruddcenter.org/what_we_do.aspx?id=10.

- 29.Kennedy C. Examining television as an influence on children's health behaviors. Journal of pediatric nursing. 2000;15:272–281. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2000.8676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Latner JD, Rosewall JK, Simmonds MB. Childhood obesity stigma: association with television, videogame, and magazine exposure. Body Image. 2007;4:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wal JSV. The relationship between body mass index and unhealthy weight control behaviors among adolescents: The role of family and peer social support. Economics & Human Biology. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schvey NA, Puhl RM, Brownell KD. The impact of weight stigma on caloric consumption. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:1957–1962. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein H, Shiffman KS. Thin is "in" and stout is out" what animated cartoons tell viewers about body weight. Eat Weight Disord. 2005;10:107–116. doi: 10.1007/BF03327532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Himes SM, Thompson JK. Fat stigmatization in television shows and movies: a content analysis. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:712–718. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lapierre MA, Vaala SE, Linebarger DL. Influence of licensed spokescharacters and health cues on children's ratings of cereal taste. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:229–234. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dalton MA, Tickle JJ, Sargent JD, Beach ML, Ahrens MB, Heatherton TF. The incidence and context of tobacco use in popular movies from 1988 to 1997. Preventive medicine. 2002;34:516–523. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin JL. What do animals do all day? The division of labor, class bodies, and totemic thinking in the popular imagination. Poetics. 2000;27:195–231. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sargent JD. Smoking in movies: impact on adolescent smoking. Adolesc Med Clin. 2005;16:345–370. doi: 10.1016/j.admecli.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. [Accessed March 17, 2012];Guidelines for the Portrayal of Obese Persons in the Media. 2012 http://www.yaleruddcenter.org/resources/upload/docs/what/bias/media/MediaGuidelines_PortrayalObese.pdf.

- 40.Tanski SE, Stoolmiller M, Gerrard M, Sargent JD. Moderation of the association between media exposure and youth smoking onset: Race/ethnicity, and parent smoking. Prevention Science. 2012;13:55–63. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0244-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]