A new era of academic medicine is upon us. The current funding climate for research has many medical schools throughout the United States initiating new strategies to conserve costs while still trying to maintain excellence in their tripartite mission of research, education, and clinical care. New measures have been instituted at many schools in which faculty salaries must be balanced by sources of income, including effort on extramural grants, clinical relative value units, educational relative value units, and administrative effort, among others. With its clinical and research skills, one group of individuals, the physician-scientist, is particularly well equipped to face these new challenges. In his book, The Vanishing Physician-Scientist? (1), Andrew Schafer broadly defines a physician-scientist as a physician (with an MD degree or an MD combined with other advanced degrees) who spends most of his/her professional effort engaging in research that seeks knowledge about human health and disease. Because the nature of biomedical research has changed over the decades, so too has the nature and breadth of research conducted by physician-scientists (ranging from basic laboratory studies to translational studies involving human tissues, humans, or human populations). Physician-scientists can engage in all aspects of the medical school tripartite mission, and are seemingly highly marketable. Physician-scientists are also natural candidates for leadership positions (eg, department chairs, center directors, and deans), because they are among the few individuals who can bridge crucial clinical and research issues at the administrative level. But their marketability may very well be their vulnerability in the current academic climate. Recent statistics reported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and others identify worrisome trends in pre- and postdoctoral training that cast some doubt on the future of physician-scientists in academics.

“Physician scientists can engage in all aspects of the medical school tripartite mission, and are seemingly highly marketable…… But, their marketability may very well be their vulnerability in the current academic climate.”

Dual-degree MD-PhD programs (including those funded by the NIH, known as Medical Scientist Training Programs [MSTPs]) have been a proven training ground for physician-scientists since the mid-1960s. A recent study by Brass et al (2) examined the career choices of MD-PhD graduates from 24 U.S. medical schools. The study noted a recent significant change in the career choices of MD-PhD graduates: namely, the percentage of graduates choosing traditional, more research-intensive specialties (medicine, pediatrics, neurology, and pathology) has gradually fallen from over 70% to just over 50% in the timeframe 1965 through 1978 to 1999 through 2007, whereas those choosing imaging- and procedure-oriented specialties (dermatology, radiation oncology, surgery, and ophthalmology) rose during the same timeframe from under 10% to over 20%. The worrisome significance of this trend becomes apparent when the percentage of MD-PhD graduates in private practice is considered; in the traditional specialties, the percentage in private practice is about 13%, whereas in procedure-oriented specialties, that number rises to a striking 34% (2). An issue not specifically interrogated in this study was whether this attrition into private practice is a consequence of the specialty choices themselves or a result of failure to integrate research training opportunities in those specialties.

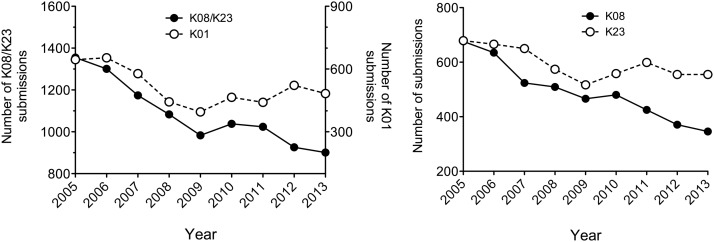

Protected research time during specialty training (residency and fellowship) proves especially crucial for long-term retention in academics. The NIH K award program is a largely salary-based award program to support an intense research training phase between fellowship and an independent faculty position, a period during which junior researchers build their research credentials to compete for academic jobs. Two K award mechanisms (K08 and K23) are designed exclusively for physician-scientists, with the K08 awarded to investigators performing basic and translational research and the K23 awarded to investigators performing clinical research. As shown in Figure 1, the total number of K08/K23 submissions to the NIH has been steadily declining since 2005, whereas submission of K01 grants (those that go to PhD-only scientists) have shown stabilization or a slight increase in recent years. Perhaps more concerning for the future of basic science research is that the decline in physician-scientist K award submissions is largely accounted for by a decline in the K08 mechanism, a finding that reflects a shift away from basic bench and translational research to more clinically oriented research. This declining trend in K08 submissions is observed at the individual institute level, including the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, through which most endocrine physician-scientists are funded. Indeed, this diminishing group of basic/translational physician-scientists is the very one we count upon to submit original research to Molecular Endocrinology. What remains unanswered is whether the recent academic climate, which emphasizes that compensation be balanced by revenue, has been contributing to the overall K08/K23 grant submission trends. But it is hard to imagine that it has not contributed. According to the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases, the number of combined K08 and K23 awardees who turned to private practice just 5 years after their awards ended rose to over 20% in 2011 from just under 10% in 2007.

Figure 1.

K award submissions to the National Institutes of Health by year. Data are from the National Institutes of Health Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (http://report.nih.gov/success_rates/index.aspx), accessed March 16, 2014.

The trends described here suggest collectively that physicians are declining to pursue research, especially basic science research, in their immediate postgraduate and early faculty phases. However, there does appear to be a solution in our midst. A working group of the Advisory Committee to the NIH Director found that only about 5% of full-time MD faculty at academic U.S. medical centers held NIH funding in 2011 and 2012, whereas over 28% of MD-PhD dual-degree faculty held NIH funding (3). This striking difference emphasizes the value of focusing efforts on dual-degree training programs (or PhD training in the post-MD period) to bolster the physician-scientist workforce. Nevertheless, MD-PhD training programs are not immune to the financial restraints medical schools are facing today. Recently, the Concord Monitor reported that Dartmouth University elected to suspend recruitment into its MD-PhD program pending a reassessment of its “strategic goals of sustainability and excellence” (4). This and similar recent decisions raised fears in the training community that the long-term educational mission of medical schools is falling prey to short-term financial considerations (note that after the outcry from the local academic community, the decision by Dartmouth University has since been partially reversed). Therefore, it is imperative that we as an academic community recommit our efforts to ensuring the training of the next generation of physician-scientists. Several concrete measures can be taken:

1) Increase dual-degree training investment by the NIH. Whereas MD-PhD programs supported by institutional funds have reported success in training students, data consistently show that MSTP-funded programs (likely because of their rigorous accountability, defined programmatic curricula, and full tuition/stipend support) have better retention rates and overall student success, as measured by a variety of outcomes (5, 6). Because most MD-PhD programs recruit students regionally, broadening of the MSTP to regions of the country with less representation (eg, the South, Southwest, and Midwestern regions) will help to extend dual-degree opportunities and enhance diversity in the physician-scientist workforce.

2) Increase dual-degree training investment by medical schools. Data from the Association of American Medical Colleges show that applications to MD-PhD programs nationally have increased about 2% annually (on average) over the last 6 years (7). Therefore, an interest to pursue the physician-scientist pathway at the predoctoral level remains robust. Investment in dual-degree training by medical schools could take many forms. For example, schools should consider the option of creating new MD-PhD training positions by redeployment of some resources used to support PhD- and MD-only training positions. Establishing programs that offer PhD degrees in the post-MD training period (residency and fellowship) would encourage rigor and structure into research training while additionally diversifying the student body in graduate programs. Additionally, some institutions (such as Washington University in St. Louis and Indiana University) have been successful at leveraging philanthropic support to generate large endowments that support dual-degree MD-PhD training. Clearly, all of these are the types of commitments that will require reevaluation of training priorities at the highest levels of medical school administration.

3) Increase the number and breadth of postgraduate training programs that integrate research and clinical training. Several highly committed institutions have initiated so-called physician-scientist training programs, which provide one-on-one mentorship and protected time for MD trainees to engage in research during residency and fellowship training. Although many of these programs are based in internal medicine residencies/fellowships, in recent years, there has been growth into other specialties (such as the Morris Green Physician Scientist Development Program for pediatricians at Indiana University and the Clinical Neuroscientist Training Program for neurologists at Yale University). Given the changing specialty choices of MD-PhD graduates described earlier, the establishment of physician-scientist training programs in procedure- and imaging-oriented specialties will be especially important.

4) Support the mentors of future physician-scientists. The decline in K08 submissions and the increase in percentage of former K awardees entering private practice are alarming trends. What's the problem here? A mantra we hear often in academics is mentorship, mentorship, mentorship. Indeed, the best mentors for physician-scientists are physician-scientists themselves. The importance of mentorship was recognized by the NIH, which developed a unique award mechanism called the K24. The K24, a salary-based award, was conceived to allow productive, clinically oriented physician-scientists to have protected time to mentor the next-generation of clinical investigators. Yet no such award exists to support basic science-oriented physician-scientist mentors. Although it is unclear whether the K24 mentorship award has helped mitigate the decline in K23 submissions, it is not far-fetched to assume that it has. Broadening the K24 program to include basic science-oriented physicians could be one step in the right direction, but medical schools also need to invest in these individuals, whether through competitive internal mentorship support programs or through incentives based on training accomplishments.

The measures cited above should be considered only a framework for further curricular and funding reprioritizations that need to be initiated by the NIH and medical school administrations. The NIH has recognized the challenges facing physician-scientists and, to this end, has established a Working Group on Physician-Scientist Workforce (8) to provide a comprehensive assessment of the state of the workforce and the impact of current NIH funding policies. But impactful change can happen only when medical schools recognize that there is an emerging problem. Fortunately, many schools have made that recognition, and they should serve not only as examples for everyone else but also as the most vocal advocates for change.

Raghavendra G. Mirmira, MD, PhD

Editor, Molecular Endocrinology

Acknowledgments

I thank Dr M. Harrington and Dr C. Evans-Molina for providing feedback on this editorial.

Research in R.G.M.'s lab is funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK060581 and R01 DK083583), the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, the American Diabetes Association, the George and Francis Ball Foundation, and the Ball Brothers Foundation. R.G.M. is director of a National Institutes of Health-funded Medical Scientist Training Program award (GM 077229).

Disclosure Summary: The author reports no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

- MSTP

- Medical Scientist Training Program.

References

- 1. Schafer AI. The Vanishing Physician-Scientist? Gordon S, Nelson S, eds. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brass LF, Akabas MH, Burnley LD, Engman DM, Wiley CA, Andersen OS. Are MD-PhD programs meeting their goals? An analysis of career choices made by graduates of 24 MD-PhD programs. Acad Med. 2010;85:692–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Advisory Committee to the Director: Working Group on Biomedical Research Workforce. National Institutes of Health website. http://report.nih.gov/investigators_and_trainees/ACD_BWF/. Updated June 14, 2012 Accessed March 16, 2014

- 4. Fleisher C. Geisel to suspend dual degrees. Concord Monitor website. February 13, 2014. http://www.concordmonitor.com/news/work/business/10688607–95/geisel-to-suspend-dual-degrees Accessed March 19, 2014

- 5. Jeffe DB, Andriole DA, Wathington HD, Tai RH. Educational outcomes for students enrolled in MD-PhD programs at medical school matriculation, 1995–2000: a national cohort study. Acad Med. 2014;89:84–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jeffe DB, Andriole DA. A national cohort study of MD-PhD graduates of medical schools with and without funding from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences' Medical Scientist Training Program. Acad Med. 2011;86:953–961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. MD-PhD applicants, acceptees, matriculants, and graduates of U.S. medical schools by sex, 2001–2012. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://www.aamc.org/data/facts/enrollmentgraduate/ Accessed March 16, 2014

- 8. Advisory Committee to the Director: Working Group on Physician-Scientist Workforce. National Institutes of Health website. Available from: http://acd.od.nih.gov/psw.htm. Updated June 3, 2013 Accessed March 19, 2014