Abstract

Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) is a paracrine factor involved in organogenesis, tissue repair, and wound healing. We report here that HGF promotes osteogenic differentiation through the transcription of key osteogenic markers, including osteocalcin, osterix, and osteoprotegerin in human mesenchymal stem cells and is a necessary component for the establishment of osteoblast mineralization. Blocking endogenous HGF using PHA665752, a c-Met inhibitor (the HGF receptor), or an HGF-neutralizing antibody attenuates mineralization, and PHA665752 markedly reduced alkaline phosphatase activity. Moreover, we report that HGF promotion of osteogenic differentiation involves the rapid phosphorylation of p38 and differential regulation of its isoforms, p38α and p38β. Western blot analysis revealed a significantly increased level of p38α and p38β protein, and reverse transcription quantitative PCR revealed that HGF increased the transcriptional level of both p38α and p38β. Using small interfering RNA to reduce the transcription of p38α and p38β, we saw differential roles for p38α and p38β on the HGF-induced expression of key osteogenic markers. In summary, our data demonstrate the importance of p38 signaling in HGF regulation of osteogenic differentiation.

Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), also known as scatter factor, is a pleiotropic factor that regulates cell proliferation, motility, morphogenesis, and angiogenesis. HGF has also been shown to participate in organogenesis, tissue repair, neuronal induction, and bone remodeling (1). HGF acts as a paracrine factor throughout the body by binding to its tyrosine kinase receptor, c-Met, and activating a signal transduction cascade. HGF has robust effects on human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs); blocking HGF bioactivity reduces hMSC migration (2) and blocking the HGF receptor (c-MET) diminishes both proliferation and differentiation (3). hMSCs are precursors for the generation of different mesenchymal cell lineages, including osteoblasts, adipocytes, myoblasts, chondroblasts, and fibroblasts (3). MSCs have been used to repair bone defects in animal models (4–8) and MSCs overexpressing bone morphogenetic protein-2 were shown to restore bone defects in aged rats (9). Along these lines, HGF likely primes hMSCs toward the osteoblastic pathway. Therefore, HGF as a driver of hMSC osteogenic differentiation has the potential to promote bone repair and maintain bone homeostasis, but information on the mechanism(s) of HGF-induced hMSC-mediated bone repair/regeneration is lacking.

HGF activates an array of signaling cascades in hMSCs, including rapid phosphorylation of ERK, AKT/PI3K (10, 11), and as we report here, p38. p38 MAPK consists of 4 identified isoforms, p38α, p38β, p38δ, and p38γ, and the rapid induction of p38α and p38β isoforms has been reported to be important for skeletogenesis and bone homeostasis (12). Moreover, the loss of p38 signaling through the knockout of p38 phosphatases, MKK3 and MKK6, and the loss and/or reduction of p38α and -β lead to a decrease in bone maturation and maintenance (12). p38 has been shown to directly phosphorylate RUNX2 (leading to possible protein stabilization) and is involved in promoting RUNX2 and osterix (OSX) gene expression (13, 14), key transcription factors for osteoblast differentiation. p38 has also been reported to be involved in bone morphogenetic protein-4 gene expression, which is important for bone formation and osteoblast differentiation (15, 16). Taken together, the data presented here highlight the important role that p38 plays on bone formation and maintenance and osteoblast differentiation.

The current study was done to determine the role of HGF/c-MET, through the activation of p38, during hMSC osteogenic differentiation and whether blocking p38α or p38β inhibited HGF-induced expression of key osteoblast markers. The results of this study, showing that HGF promotes osteogenic maturation of hMSCs through the p38 pathway, provide important insight into the role of HGF during osteogenic differentiation and led to a better understanding of the possible mechanism of HGF/p38 signaling in the therapeutic potential of hMSCs.

Materials and Methods

Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell (MSCs) isolation and cell culture

hMSCs were isolated and cultured as previously described (17), from postmortem thoracolumbar (T1–L5) vertebral bodies of donors of various ages (4–30 years of age) immediately after death from traumatic injury. hMSCs from a 4- and 7-year-old male were used in these studies. Guidelines were followed as outlined by the Committee on the Use of Human Subjects in Research at the University of Miami. Cells were grown in Expansion media, DMEM-low glucose media, containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone Laboratories; catalog no. 30039), 20 mM ascorbic acid (Fluka/Sigma; catalog no. 49752), an essential fatty acid solution (18), and antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin) (Gibco: catalog no. 15140) at 37°C on 10 ng/mL fibronectin (Sigma; catalog no. F2518)-coated flasks (Nunclon) in 21% O2, 5% CO2, and 92% N2. Media was changed every 3 days, and cells were subcultured upon reaching 80% confluence. In expansion conditions cells were plated at 1000 cells/cm2.

Osteogenic differentiation

During differentiation, cells were grown in Osteogenic media, αMEM-low glucose media, containing 10% FBS (Hyclone; lot no. 30039), 20 mM ascorbic acid (Fluka/Sigma; catalog no. 49752), an essential fatty acid solution (18), antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin) (Gibco; catalog no. 15140), and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate at 37°C on 10 ng/mL fibronectin (Sigma; catalog no. F2518)-coated flasks (Nunclon) in 21% O2, 5% CO2, and 92% N2. Cells for osteogenic differentiation were plated at 10 000 cells/cm2, and day 0 began when cells were 100% confluent with subsequent media changes every 3–4 days.

HGF treatment

Human MSCs were cultured in T75 flasks in standard growth medium (10% FBS). At 50% confluence, cells were treated with 10, 20, 40, or 100 ng/mL HGF (Peprotech) dissolved in 0.01% BSA in PBS. The ideal concentration of HGF was determined to be 40 ng/mL and was used for the subsequent experiments. For long-term experiments (ie, mineralization) HGF was added during media changes, which occurred every 3–4 days. For short-term experiments a single treatment of HGF was used.

Cell proliferation assay

Cells were plated at 1000 cells/cm2, and on the following day (day 0) they were treated with or without HGF neutralizing antibody MAB294 at either 100 ng/mL or 300 ng/mL. After 30 minutes, cells were treated with or without HGF (40 ng/mL). Cells were allowed to proliferate for 5 days. On day 5, cells were counted using a hemocytometer.

Western blot

Whole-cell lysates were prepared with Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer. Protein concentration was determined using BCA system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Western immunoblotting was performed as described previously (19). Briefly, 5 μg of total protein was resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore Corp). The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in PBS buffer containing 0.1% Tween 20 for 1 hour, and then incubated at 4°C overnight with primary antibodies against phospho-p38, p38, p38α, p38β (each at 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), phospho-p38α (Millipore,) and α-tubulin (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). After overnight incubation unbound primary antibodies were removed by rinsing the membranes 3 × for 10 minutes with Tris-buffered saline. Membranes were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2000) for 1 hour at room temperature and then rinsed 3 × for 10 minutes with Tris-buffered saline. ECL-plus Western Blot system (Amersham Bioscience) was used to image the protein bands. Band intensities were compared using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MA) and densitometric analysis was obtained by normalizing to loading control (α-tubulin) and where appropriate to total p38 or total cMet.

RNA interference with p38 and p38 isoforms

Transient transfection of small interfering RNA (siRNA) in hMSCs was performed using TransIT-TKO transfection reagent with either p38α siRNA, p38β siRNA, or nonsilencing control siRNA (a non homologous, scrambled sequence equivalent) (Cell Signaling Technology). In brief, hMSCs were harvested by trypsinization and plated at 3000 cells/cm2 in 6-well plates. Within 24 hours, 250 μL of Opti-Mem I-reduced Serum Media, 10 μl of TransIT-TKO transfection reagent, and 100 nM control siRNA or p38 siRNA were combined and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes. Following incubation TKO/siRNA complex was added drop-wise to wells containing cells. hMSCs were transfected for 4 days; at that time protein was collected to determine knockdown level of p38α and p38β. At the beginning of day 4 the cells were treated with HGF (40 ng/mL). RNA from cells treated with p38α siRNA, p38β siRNA, and control siRNA was collected after 2 days of subsequent HGF treatment.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from hMSCs with RNAqueous-4PCR Kit following manufacturer's procedures (Ambion). The amount and quality of total RNA were determined using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer. cDNA was created by reverse transcribing 2 μg of total RNA with SuperScript II (Invitrogen) following manufacturer's instructions. For RT-qPCR, 100 ng of cDNA was added to 12.5 μL of SYBRGreen, 0.375 μL ROX, 3.125 μL H2O, and 2 μL primer pairs. PCR was amplified using a Stratagene 3500 set at 40 cycles of 94°C for 1 minute, 55 to 60°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 2 minutes. The ΔΔCT method, using RPL13a as the internal control, was used to analyze the results.

ELISA

The level of endogenous HGF was determined from cell culture supernates. Briefly, cellular media were collected, centrifruged at 1000 × g for 15 minutes to remove any cellular debris, and supernatant was then collected and stored frozen (−80°C) until the ELISA was performed. ELISA was performed according to manufacturer's protocol (R&D Systems). Each sample was run in duplicate, with 3 separate experiments.

Alkaline phosphatase activity

hMSCs were seeded in 12-well plates (100 000 cells per well). The next day media were replaced with osteogenic media, and cells were treated with c-MET inhibitor PHA665752 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at concentrations of 0 (C), 0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, or 1 μM for 3 days. Alkaline phosphatase activity was evaluated at the end of culture day 3. hMSC alkaline phosphatase activity was measured in triplicate as previously described (17). Briefly, cells were rinsed with PBS, fixed with ice-cold 2% paraformaldehyde/0.2% gluteraldehyde for 1 hour at 4°C, and then stained for 30 minutes at 37°C with stain solution (8 mg naphthol AS-TR phosphate [Sigma] in 0.3 mL N-N′-dimethylformamide [Sigma] and 24 mg of fast blue BB [Sigma] in 30 mL 100 mM Tris-HCL, pH 9.6, and 10 mg of MgCl2 (Sigma) in final mixed stain solution with pH 9.0). Cells were rinsed extensively with water, and images were taken by inverted microscope with camera.

Mineralization assay

hMSCs were seeded in 12-well plates (100 000 cells per well). The next day media were replaced with osteogenic media and cells were treated with c-MET inhibitor PHA665752 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at concentrations of 0 (C), 0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, or 1 μM at each media change for 17 days. The same protocol was used with HGF neutralizing antibody, at concentrations of 5, 10, 100, 200, and 300 ng/mL (MAB294; R&D systems) for a total of 10 days. Cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde /0.2% gluteraldehyde for 1 hour, and then stained with 40 mM alizarin red-S as previously described (17). Stain was quantified (562 nM) after solubilizing in 10% cetylpyridinium chloride (10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0) (20).

Statistical analysis

Experiments were performed in triplicate. Group data are represented as mean ± SD. Quantitative data were analyzed using Student's t test; a value of P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

HGF increases the expression of key osteogenic markers

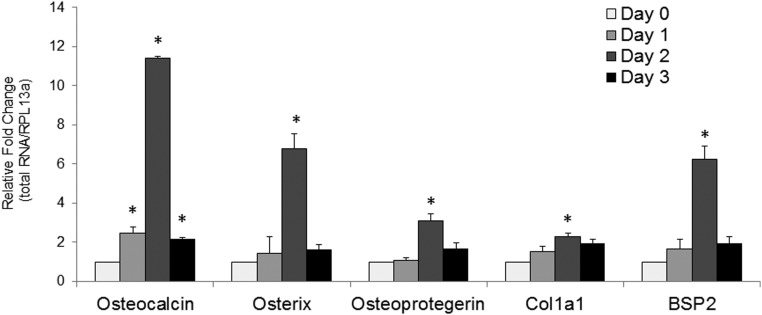

To determine the role of HGF on hMSC osteogenic differentiation/maturation, we used RT-qPCR to evaluate the effect of HGF treatment on the gene expression of key osteogenic markers, osteocalcin (OCN), OSX, osteoprotegerin (OPG), bone sialoprotein 2 (BSP2), and collagen 1a1 (COL1a1) (Figure 1). One day after a single treatment with HGF (40 ng/mL) revealed significantly (P < .05) increased expression of OCN. By day 2 (48 hours after treatment) all 5 genes examined displayed a significant increase in gene expression. At day 3 (72 hours after HGF treatment) the gene expression level of OCN remained significantly greater than the basal (control) levels, whereas OSX, OPG, COL1a1, and BSP2 returned to basal levels. Using the ΔΔCT method our results show that after 2 days of HGF treatment OCN displayed the largest increase in expression with an 11-fold increase over basal levels, whereas OSX displayed a roughly 6-fold increase in gene expression compared with basal levels. OPG displayed a roughly 3-fold increase in gene expression 2 days after HGF treatment.

Figure 1.

HGF increases the level of key osteogenic markers. RT-qPCR of OCN, Osterix, OPG, Collagen1a1, and Bone Sialoprotein2 (BSP2) at 1, 2, and 3 days after a single treatment of HGF (40 ng/mL). Relative values were calculated by ΔΔCT method, with each gene normalized to housekeeping gene RPL13α and its control (day 0). Error bars represent SD of triplicate experiments, with *, P < .05 vs control (Student's t test). Control has no error bar because the values obtained for each experiment were set at 1 for subsequent fold change calculation.

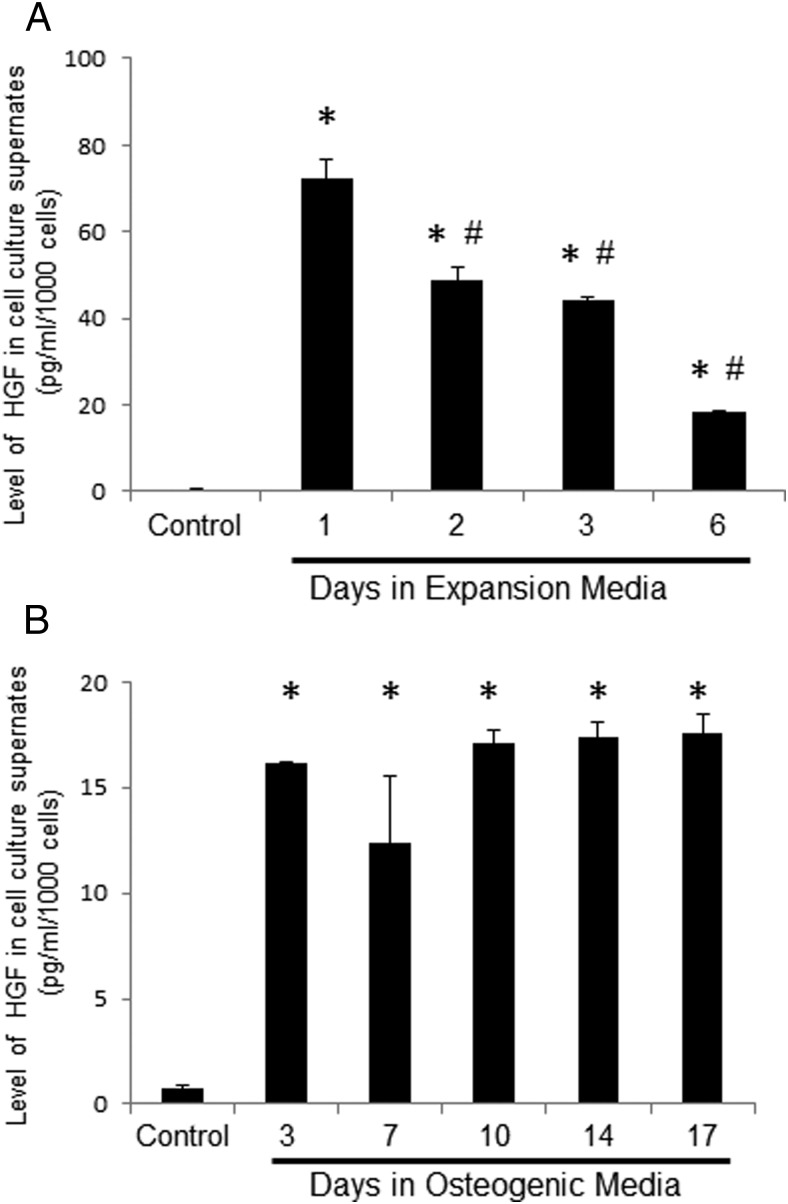

To determine the level of endogenous HGF during expansion of hMSCs and subsequent differentiation, we used ELISA. HGF rapidly increased in the culture media within 24 hours of media changes in expansion conditions (Figure 2A). In expansion conditions cells were plated at 1000 cells/cm2 (ie, cells were only 30%–40% confluent at the start of the experiment). The level of HGF quickly decreases after 2 days in expansion media with significant decreases from days 1–6 (P < .05). In contrast, the level of HGF remained in a steady state during differentiation (Figure 2B). In differentiation conditions, cells were plated at 10 000 cells/cm2, and experiments began when cells were 100% confluent. The level of HGF quickly accumulated after 3 days in differentiation media, and the rate of HGF production/utilization was maintained in a steady state through day 17.

Figure 2.

Endogenous level of HGF in expansion and differentiation conditions. Endogenous levels of HGF in cell media were determined by ELISA at 550 nM. A, Media were collected from expansion conditions on day 0 (control), 1, 2, 3, and 6. B, Media were collected from differentiation conditions on day 0 (control), 3, 7, 10, 14, and 17. The average absorbance was normalized to total cell number. *, P < .05 vs control using Student's t test; #, P < .05 vs day 1 using Student's t test.

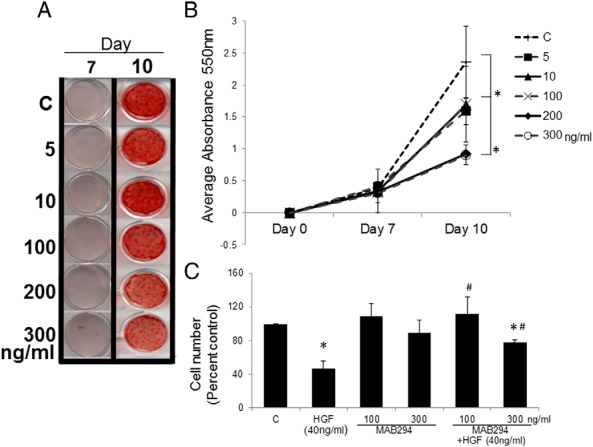

Blocking endogenous HGF signaling disrupts mineralization

To further characterize the role of HGF on osteogenic maturation, we blocked the HGF signaling pathway by 2 independent methods. In the first, HGF-neutralizing antibody significantly reduced mineralization in a dose-dependent manner. As expected in these cells, there was very little mineralization at day 7, and no significant differences were seen with or without HGF-neutralizing antibody at day 7 (Figure 3, A and B). However, at day 10, a significant dose response was detected in mineralization using HGF-neutralizing antibody. Although 5 and 10 ng/mL showed no significant change in mineralization compared with control, 100, 200, and 300 ng/mL of HGF-neutralizing antibody caused significant decreases in mineralization (P < .05) (Figure 3, A and B). To show that HGF-neutralizing antibody is blocking HGF activity we performed a cell proliferation assay. At day 5, cell proliferation was significantly (P < .05) lower in HGF-treated cells, as measured by total cell number. HGF-neutralizing antibody alone had no significant effect on cell proliferation compared with control. Most importantly, HGF-neutralizing antibody blocked the HGF-induced decrease in cell proliferation. Cells treated with 100 ng/mL of HGF-neutralizing antibody plus HGF (40 ng/mL) did not significantly differ from control cells but did proliferate significantly more than HGF-treated cells (P < .05). A higher dose of neutralizing antibody (300 ng/mL) in combination with HGF (40 ng/mL) also displayed a significantly higher cell proliferation than HGF-treated cells (P < .05) but also was significantly lower in cell proliferation than control (P < .05).

Figure 3.

HGF neutralizing antibody reduces mineralization. hMSCs were treated with 0 (C), 5, 10, 100, 200, or 300 ng/mL of HGF neutralizing antibody (R&D; MAB294) during media changes every 3–4 days and then stained using Alizarin Red-S on days 7 and 10 (panel A). Mineralization was then quantified and absorbance measured at 550 nm (panel B). Cell proliferation assay of HGF neutralizing antibody (100 and 300 ng/mL) with or without HGF (40 ng/mL) at day 5 (panel C). Error bars represent SD. *, P < .05 vs control by Student's t test; #, P < .05 vs HGF-treated using Student's t test. C, control.

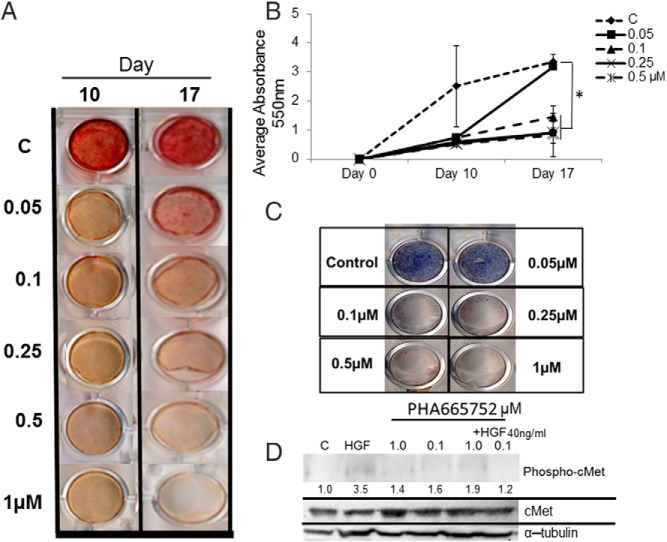

To show that the effect of HGF on mineralization was through its receptor, c-MET, we treated hMSCs with PHA665752, a c-MET inhibitor, and then quantified calcium accumulation during mineralization. We observed a significant (P < .05), concentration-dependent (0.1–1 μM) decrease in mineralization across days 10 and 17 compared with control (Figure 4, A and B). PHA665752 at a lower dose, 0.05 μM, was able to significantly reduce mineralization at day 10 but did not maintain the attenuated mineralization through day 17.

Figure 4.

cMET inhibitor, PHA665752, blocks mineralization. hMSCs were treated with 0 (C), 0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, or 1 μM cMET inhibitor (PHA665752) during media changes every 3–4 days and then stained using Alizarin Red-S on days 10 and 17 (panel A). Mineralization was then quantified and absorbance measured at 550 nM (panel B). Alkaline phophosphatase activity was determined at day 3 (panel C). Western blot analysis showed a reduction of phosphorylated cMet and total cMet (α-tubulin as a loading control), with densitometry quantification shown (panel D). Error bars represent SD. *, P < .05 vs control using Student's t test. C, control.

Blocking cMET activation with PHA665752 also caused a significant, dose-dependent decrease in alkaline phosphatase activity. Three days after PHA665752 treatment (0.1, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 μM) hMSCs displayed reduced alkaline phosphatase activity (Figure 4 C). PHA665752 at a lower dose, 0.05 μM, did not attenuate alkaline phosphatase activity 3 days after treatment. Western blot analysis showed that at doses of 0.1 and 1.0 μM, PHA665752 did block HGF-induced activation of cMET (ie, phospho-cMET) (Figure 4D). Densitometric analysis showed that HGF alone produced an increase of 3.5 (350% increase) compared with control. Doses of 0.1 and 1.0 μM of PHA665752 produced cMet activation of 1.9 and 1.2 (PHA665752 +HGF), roughly 50% and 70% decreases in activation compared with HGF treated, respectively.

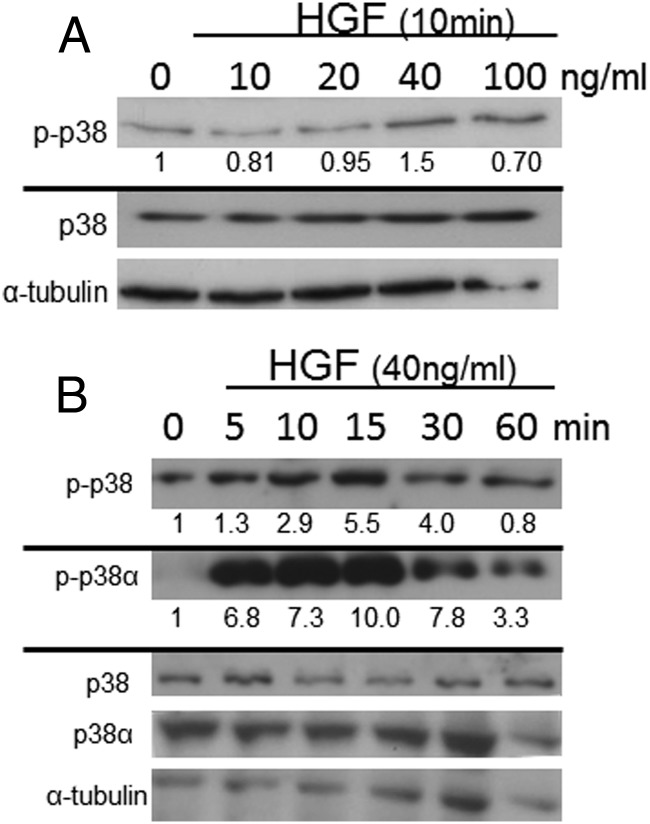

HGF rapidly phosphorylates p38 in a dose- and time-dependent manner

In view of the reports cited above that p38 is involved in skeletogenesis, we performed a dose response and time course of HGF treatment to determine whether HGF affects p38 signal transduction in hMSCs. HGF (40 ng/mL) treatment of hMSCs showed a significant increase in phosphorylation of total p38 and continued with 100 ng/mL after 10 minutes of treatment (Figure 5A). HGF concentrations of 10 and 20 ng/mL did not significantly increase p38 phosphorylation within 10 minutes of treatment. A time course with 40 ng/mL HGF led to significant phosphorylation of p38α within 5 minutes and phosphorylation of total p38 within 10 minutes (Figure 5B). Phosphorylation of both p38α and total p38 peaked at 10–15 minutes and subsequently decreased at 30 and 60 minutes. Phosphorylation of p38β was not determined at this time due to the lack of a specific phospho-p38β antibody.

Figure 5.

HGF activation of p38 is dose and time dependent. Dose response (panel A) of HGF treatment (10 minutes) of hMSCs. Time course (panel B) of HGF treatment (40 ng/mL) of hMSCs. Western blot analyses were performed on phosphorylated-p38α (p-p38α), total p38α (p38α), phosphorylated-p38 (p-p38), and total p38 (p38), with α-tubulin as a loading control (n = 3 independent experiments in triplicate, with a representative blot and densitometric quantification shown).

HFG increases the level of p38α and p38β

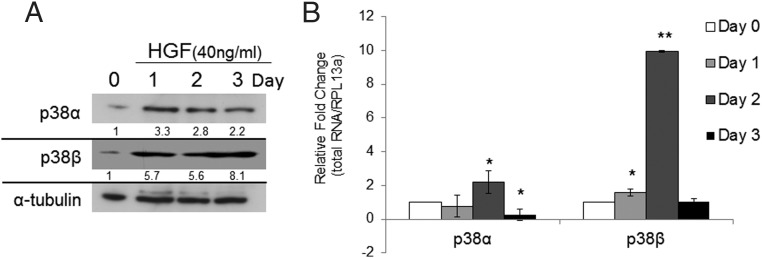

To determine whether HGF treatment on p38 signal transduction is isoform specific, we performed Western blot and RT-qPCR analyses on p38α and p38β isoforms. A single treatment of HGF (40 ng/mL) led to a transient increase in p38α and p38β in hMSCs. Western blot analysis showed an increase in both p38α and p38β on day 1. Both p38α and p38β maintained protein expression through days 2 and 3, with p38β displaying the highest increase in protein expression compared with control (Figure 6A). RT-qPCR analysis of p38 gene expression after a single HGF treatment revealed differential expression of p38α and p38β (Figure 6B). HGF (40 ng/mL) did not significantly affect gene expression levels of p38α after 1 day of treatment. However, 2 days of HGF treatment did show a significant increase in the gene expression of p38α (P < .05), followed by a significant decrease (P < 0,05) in the gene expression of p38α at day 3. HGF significantly altered the level of p38β. On day 1 expression level of p38β gene was significantly increased by HGF treatment (P < .05). The most robust response (P < .0001) to HGF treatment was seen at day 2, with a 10-fold increase in expression compared with basal levels of p38β expression. The gene expression level of p38β returned to basal levels by day 3.

Figure 6.

HGF increases the level of p38 protein (panel A) and mRNA expression (panel B). Western blot analysis (panel A) of p38α and p38β after a single treatment with HGF (40 ng/mL) on days 0, 1, 2, and 3. (n = 3 independent experiments in triplicate with a representative blot and densitometric quantification shown). B, RT-qPCR of p38 isoforms after HGF treatment (40 ng/mL) on days 0, 1, 2, and 3. Relative values were calculated by ΔΔCT method, with each gene normalized to housekeeping gene RPL13α and its control (day 0). Error bars represent SD of triplicate experiments; *, P < .05 vs control; and **, P < .0001 vs control using Student's t test. Control has no error bar because the values obtained for each experiment were set at 1 for subsequent fold change calculation.

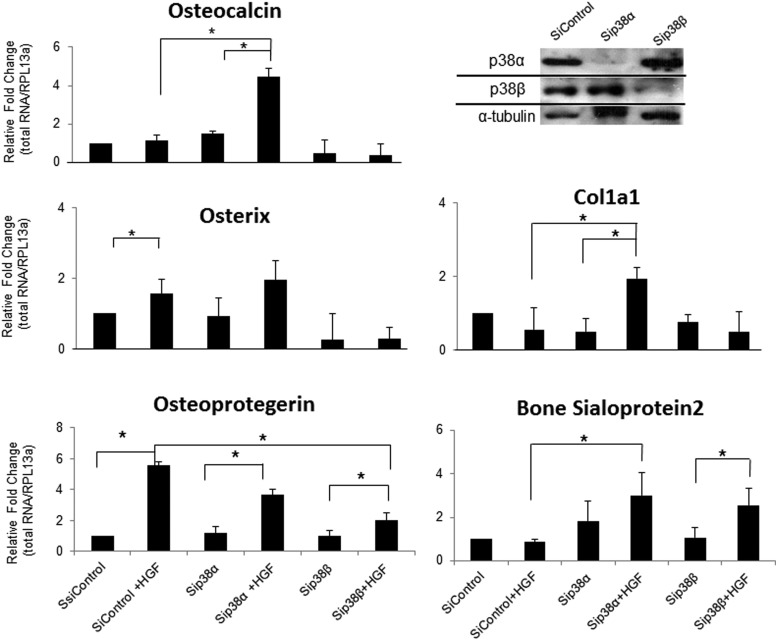

p38α and p38β differentially regulate HGF-induced expression of key osteogenic markers

siRNA was used to determine the role(s) of p38α and p38β in HGF induction of osteogenic markers. Two days of HGF treatment in siControl-treated cells significantly (P < .05) increased the transcription level of OPG and OSX compared with siControl, with a 5.5- and 1.5-fold (respectively) increase. A significant increase was not seen for OCN (P = .06), COL1a1, or BSP2 when comparing siControl vs siControl +HGF, although a significant increase was seen in Figure 1. Compared with the results seen in Figure 1, Figure 7 displays the results after a total of 6 days in culture. The change in HGF levels between day 2 and day 6 may be contributing to the lack of effect of HGF on siControl. When HGF is added to the MSCs on day 2, the level of HGF is still elevated and/or the rate of turnover is lower than on day 6. It is possible that the 40 ng/mL plus the elevated level of endogenous HGF is what is needed to drive the gene transcription of OCN and other osteogenic markers. Also it is possible that on day 6 the rate of turnover is too high for the 40 ng/mL of HGF to have an effect on siControl-treated cells.

Figure 7.

p38β and p38α mediate HGF-induced osteogenic gene expression. RT-qPCR was performed on RNA from hMSCs exposed to 4 days of siRNA control, siRNA p38α, or siRNA p38β. On day 4 the cells were then treated or not with HGF (40 ng/mL) for an additional 2 days (6 days total). Relative values were calculated by ΔΔCT method, with each gene normalized to housekeeping gene RPL13α and its control (day 0) (left panels and 2 lower right panels). Western blot analysis of the knockdown of p38α and p38β 4 days after siRNA treatment (upper right panel). Error bars represent SD of 3 independent experiments; *, P < .05 vs control using Student's t test. siControl has no error bar because the values obtained for each experiment were set at 1 for subsequent fold change calculation.

The results of HGF treatment in cells treated with either p38α siRNA or p38β siRNA show significant changes in gene expression. RT-qPCR data reveal a significant (P < .05) increase in the expression of OCN, OPG, and COL1a1 when HGF-treated cells were exposed to p38α siRNA. However, although the data show a trend, HGF did not significantly increase the expression of OSX or BSP2 in p38α siRNA-exposed cells. Most importantly, HGF did not induce the expression of OCN, OSX, or COL1a1 in cells in which the level of p38β was decreased. Cells treated with p38β siRNA failed to respond to HGF induction of gene expression, displaying a similar level of transcriptional activity as cells treated with p38β siRNA without HGF. OPG and BSP2 did show a significant increase in gene expression in p38β siRNA HGF-treated cells compared with p38β siRNA cells not receiving HGF. However, the increase in OPG was truncated compared with siControl and p38α siRNA treated with HGF; they displayed a roughly 5.5- and 3.7-fold, respectively, increase.

Discussion

The data presented herein is the first account describing the interaction of HGF, p38α, and p38β on osteogenic maturation. The HGF/p38 signal transduction pathway provides a novel mode of regulation/support for bone maintenance and bone renewal.

HGF plays a vital role in bone maintenance and bone renewal through the activation of key osteogenic markers and promoting osteoblast proliferation (1, 21). In parallel, our data show that HGF induces the expression of OCN, OPG, COL1a1, BSP2, and OSX in a transient manner. Although gene expression of these key osteogenic markers begins to rise in hMSC after 1 day of HGF treatment, we observed the most robust effect at day 2, with the levels then returning to baseline by day 3. Similar to our data, HGF (30 ng/mL) has also been reported to induce osteopontin gene expression within 24 hours (21). Using a rabbit model of osteonecrosis, Wen et al (22) reported an improvement in tissue repair when transplanted MSCs were transfected with HGF. In their model, HGF levels immediately increased following transplantation and did not decline until 2 weeks after transplantation. Recent work by Tomson et al (23) showed an increase in OSX and OCN gene expression after 7 and 12 days of treatment with HGF. In those studies experimental media were changed every 48 hours, suggesting a cumulative effect of HGF treatment after continued treatment (23). Along these lines, we have previously reported that HGF inhibits cell proliferation and, combined with 1α,25-dihydroxy vitamin D, promotes osteogenic differentiation (3, 18, 31). Thus it appears that both acute and chronic treatment with HGF promotes osteogenesis.

Using chemical inhibition of the HGF pathway we saw a marked reduction in mineralization and alkaline phosphatase activity. hMSCs produce HGF, and endogenous HGF can have autocrine and paracrine activity on the cells (3). Blocking the endogenous HGF activity, through the inhibition of c-MET activity or with an antibody neutralizing endogenous HGF, was sufficient to attenuate osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs. These results suggest that basal HGF activity is promoting bone maintenance/osteoblast differentiation. Although we did not see an increase in mineralization or alkaline phosphatase (data not shown) using 40 ng/mL of HGF, it is likely due to a ceiling effect with the endogenous HGF (Figure 2B) activity combined with the differentiation media rapidly pushing the cells toward maturation/mineralization and increasing alkaline phosphatase activity, thus making it difficult to see an increase in our system.

The role of p38 in bone development and bone maintenance is becoming widely recognized. p38α-knockout mice have reduced bone mass, and mice lacking p38α in osteoblasts display an age-dependent decrease in bone mass and bone mineral density (12, 24). Similarly, p38β-knockout mice also exhibit a diminished bone mass (12). Greenblatt et al (12) hypothesized that p38α and p38β have different functions in bone development and maintenance: p38α regulating early osteoblast differentiation and p38β regulating late osteoblast maturation. Our data show that p38β appears to have a major role in the HGF induction of genes associated with mature osteoblasts (eg, OCN). For example, HGF induction of OCN and Col1a1 are dependent on p38β. OCN, secreted solely by osteoblast, is necessary for alkaline phosphatase activity and mineralization. Additionally, HGF was not able to induce OXS gene expression in p38α- or p38β siRNA-treated cells. Therefore, OSX, a key mediator of early osteoblast differentiation, appears to require both p38α and p38β for full HGF induction. The HGF-induced expression of OPG was truncated, but not removed, with either p38α- or p38β siRNA. In contrast, BSP2 showed significant increase in gene expression in p38β siRNA-treated cells but not in p38α siRNA-treated cells. Hence, our data support the role of HGF and p38 in early and late stages of osteoblast differentiation.

Although p38α is the most abundant p38 isoform (as seen in our hMSCs, data not shown), the role of p38β is important for bone mass. As indicated above, p38β-knockout mice display a reduction in bone mass (12). Interestingly, p38α is the major isoform found in osteoclasts and is essential for osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption (25). Our data suggest that p38β is necessary for the induction of gene expression of osteogenic markers, but it is unclear whether this is due to the loss of p38β-mediated gene expression or whether p38α is acting as a direct inhibitor of genes involved in osteogenic differentiation. Moreover, the rapid activation of p38 by HGF also contributes to osteogenic differentiation. Here we show that HGF rapidly activates p38 via phosphorylation within 10 minutes of treatment. This effect is dose dependent, with at least 40 ng/mL of HGF needed to see a significant increase in p38 phosphorylation. HGF treatment also leads to increases in p38α and p38β protein levels and in their gene expression. It is likely that HGF is influencing the expression of p38 through the rapid phosphorylation of p38, and thereby maintaining the protein levels, ie, activated p38 is less likely to be degraded. Additionally, the increase in gene expression can lead to increased protein levels by days 2 and 3. HGF's dual induction and maintenance of p38 activity appear to have numerous effects on hMSCs, including the induction of key osteogenic proteins.

The p38 MAPK pathway is likely promoting osteoblast differentiation and maturation by acting as a mediator of both the activation of key osteogenic proteins and transcriptional activity of key osteogenic genes. Phosphorylation of p38 leads to downstream effects including the activation and expression of RUNX2 and OSX (26–29). Moreover, p38 plays a key role in OSX-induced expression of COL1a1 (30). Finally, p38 has been reported to be essential in mineralization and alkaline phosphatase activity during osteogenesis in MC3T3-E1 cells (31, 32), in which p38 promotes the transcription of osteogenic genes through posttranscriptional modification.

The role of p38 in HGF-mediated osteogenic differentiation and bone repair has promising therapeutic potential in that promotion of p38β over p38α might lead to a stronger HGF effect in osteogenic maturation and bone repair. The combination of p38β activity and HGF treatment in hMSCs may have important clinical applications for the treatment of bone diseases and the promotion of bone health.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Vazquez and B. Nubia Rodriguez for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by Merit Review awards from the Department of Veterans Affairs (to B.A.R., G.A.H.) and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award 7F32AR062990 (to K.M.C.). Dr Howard is the recipient of a Senior Research Career Scientist award from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- BSP2

- bone sialoprotein 2

- COL1a1

- collagen 1a1

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- HGF

- hepatocyte growth factor

- hMSCs

- human mesenchymal stem cells

- OCN

- osteocalcin

- OPG

- osteoprotegerin

- OSX

- osterix

- RT-qPCR

- reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA.

References

- 1. Grano M, Galimi F, Zambonin G, Colucci S, Cottone E, Zallone AZ, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor is a coupling factor for osteoclasts and osteoblasts in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(15):7644–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vogel S, Trapp T, Borger V, Peters C, Lakbir D, Dilloo D, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor-mediated attraction of mesenchymal stem cells for apoptotic neuronal and cardiomyocytic cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 67(2):295–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. D'Ippolito G, Schiller PC, Perez-stable C, Balkan W, Roos BA, Howard GA. Cooperative actions of hepatocyte growth factor and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in osteoblastic differentiation of human vertebral bone marrow stromal cells. Bone. 2002;31(2):269–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ichioka N, Inaba M, Kushida T, Esumi T, Takahara K, Inaba K, et al. Prevention of senile osteoporosis in SAMP6 mice by intrabone marrow injection of allogeneic bone marrow cells. Stem Cells. 2002;20(6):542–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kumar S, Mahendra G, Nagy TR, Ponnazhagan S. Osteogenic differentiation of recombinant adeno-associated virus 2-transduced murine mesenchymal stem cells and development of an immunocompetent mouse model for ex vivo osteoporosis gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15(12):1197–1206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bruder SP, Jaiswal N, Ricalton NS, Mosca JD, Kraus KH, Kadiyala S. Mesenchymal stem cells in osteobiology and applied bone regeneration. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;(355 Suppl):S247–S256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bruder SP, Ricalton NS, Boynton RE, Connolly TJ, Jaiswal N, Zaia J, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell surface antigen SB-10 corresponds to activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule and is involved in osteogenic differentiation. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13(4):655–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Livingston TL, Gordon S, Archambault M, Kadiyala S, McIntosh K, Smith A, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells combined with biphasic calcium phosphate ceramics promote bone regeneration. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2003;14(3):211–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tsuda H, Wada T, Yamashita T, Hamada H. Enhanced osteoinduction by mesenchymal stem cells transfected with a fiber-mutant adenoviral BMP2 gene. J Gene Med. 2005;7(10):1322–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang Y, Weil BR, Herrmann JL, Abarbanell AM, Tan J, Markel TA, et al. MEK, p38, and PI-3K mediate cross talk between EGFR and TNFR in enhancing hepatocyte growth factor production from human mesenchymal stem cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297(5):C1284–C1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Forte G, Minieri M, Cossa P, Antenucci D, Sala M, Gnocchi V, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor effects on mesenchymal stem cells: proliferation, migration, and differentiation. Stem Cells. 2006;24(1):23–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Greenblatt MB, Shim JH, Zou W, Sitara D, Schweitzer M, Hu D, et al. The p38 MAPK pathway is essential for skeletogenesis and bone homeostasis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(7):2457–2473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee CH, Huang YL, Liao JF, Chiou WF. Ugonin K promotes osteoblastic differentiation and mineralization by activation of p38 MAPK- and ERK-mediated expression of Runx2 and osterix. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;668(3):383–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen G, Deng C, Li YP. TGF-β and BMP signaling in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8(2):272–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tan TW, Huang YL, Chang JT, Lin JJ, Fong YC, Kuo CC, et al. CCN3 increases BMP-4 expression and bone mineralization in osteoblasts. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227(6):2531–2541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hu Y, Chan E, Wang SX, Li B. Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for osteoblast differentiation. Endocrinology. 2003;144(5):2068–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. D'Ippolito G, Schiller PC, Ricordi C, Roos BA, Howard GA. Age-related osteogenic potential of mesenchymal stromal stem cells from human vertebral bone marrow. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14(7):1115–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Curtis KM, Gomez LA, Rios C, Garbayo E, Raval AP, Perez-Pinzon MA, et al. EF1α and RPL13a represent normalization genes suitable for RT-qPCR analysis of bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells. BMC Mol Biol. 2010;11(1):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen K, Perez-Stable C, D'Ippolito G, Schiller PC, Roos BA, Howard GA. Human bone marrow-derived stem cell proliferation is inhibited by hepatocyte growth factor via increasing the cell cycle inhibitors p53, p21 and p27. Bone. 2011;49(6):1194–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stanford CM, Jacobson PA, Eanes ED, Lembke LA, Midura RJ. Rapidly forming apatitic mineral in an osteoblastic cell line (UMR 106-01 BSP). J Biol Chem. 1995;270(16):9420–9428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen K, Aenlle KK, Curtis KM, Roos BA, Howard GA. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D together stimulate human bone marrow-derived stem cells toward the osteogenic phenotype by HGF-induced up-regulation of VDR. Bone. 2012;51(1):69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wen Q, Jin D, Zhou CY, Zhou MQ, Luo W, Ma L. HGF-transgenic MSCs can improve the effects of tissue self-repair in a rabbit model of traumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tomson PL, Lumley PJ, Alexander MY, Smith AJ, Cooper PR. Hepatocyte growth factor is sequestered in dentine matrix and promotes regeneration-associated events in dental pulp cells. Cytokine. 2013;61(2):622–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thouverey C, Caverzasio J. The p38α MAPK positively regulates osteoblast function and postnatal bone acquisition. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69(18):3115–3125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Böhm C, Hayer S, Kilian A, Zaiss MM, Finger S, Hess A, et al. The α-isoform of p38 MAPK specifically regulates arthritic bone loss. J Immunol. 2009;183(9):5938–5947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ortuño MJ, Ruiz-Gaspà S, Rodríguez-Carballo E, Susperregui AR, Bartrons R, Rosa JL, et al. p38 regulates expression of osteoblast-specific genes by phosphorylation of osterix. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(42):31985–31994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ulsamer A, Ortuño MJ, Ruiz S, Susperregui AR, Osses N, Rosa JL, et al. BMP-2 induces Osterix expression through up-regulation of Dlx5 and its phosphorylation by p38. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(7):3816–3826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee KS, Hong SH, Bae SC. Both the Smad and p38 MAPK pathways play a crucial role in Runx2 expression following induction by transforming growth factor-beta and bone morphogenetic protein. Oncogene. 2002;21(47):7156–7163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hou X, Shen Y, Zhang C, Zhang L, Qin Y, Yu Y, et al. A specific oligodeoxynucleotide promotes the differentiation of osteoblasts via ERK and p38 MAPK pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(7):7902–7914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ortuño MJ, Susperregui AR, Artigas N, Rosa JL, Ventura F. Osterix induces Col1a1 gene expression through binding to Sp1 sites in the bone enhancer and proximal promoter regions. Bone. 2013;52(2):548–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guicheux J, Lemonnier J, Ghayor C, Suzuki A, Palmer G, Caverzasio J. Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Jun-NH2-terminal kinase by BMP-2 and their implication in the stimulation of osteoblastic cell differentiation. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(11):2060–2068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Don MJ, Lin LC, Chiou WF. Neobavaisoflavone stimulates osteogenesis via p38-mediated up-regulation of transcription factors and osteoid genes expression in MC3T3–E1 cells. Phytomedicine. 2012;19(6):551–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]