Abstract

We examined pathogenic characteristics in Japanese children with type 1 diabetes presenting before 5 years of age. The subjects were 23 Japanese children, 9 males and 14 females, 1.1–4.8 yr of age at diagnosis. The majority had severe metabolic decompensation accompanied by complete absence of β-cell function at diagnosis. We found a high frequency of preceding viral illness (41.7%) among them. The prevalence of antibodies to GAD and IA-2 at diagnosis in young children were significantly lower than those in older cases diagnosed after 5 yr of age (31.6% vs. 86.3%, 47.1% vs. 82.5%, respectively). These findings suggest that non-autoimmune mechanisms or age-related differences in autoimmunity could be involved in the pathogenesis of diabetes in young children. In regard to diabetes-related HLA-DRB1 and DQB1 alleles, all subjects had high-risk genotypes in both alleles. On the other hand, none of the patients had any of the protective genotypes in either allele. In regard to haplotypes, the frequencies of DRB1*0405-DQB1*0401 and DRB1*0901/ DQB1*0303 were 60.9% and 52.2%, respectively, and both these haplotypes are associated with strong susceptibility to type 1 diabetes. Patients with early-childhood onset may have diabetes-related autoimmunity and genetic backgrounds different from those of patients diagnosed at a later age.

Keywords: type 1 diabetes, young children, autoantibodies, HLA

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes is generally caused by autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing β-cells in the pancreas of genetically susceptible subjects. The most important genes contributing to disease susceptibility are located in the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II locus on the short arm of chromosome 6. Several environmental factors have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of this disease (1,2,3).

Detection of autoantibodies, such as those to insulin (IAA), glutamic acid decarboxylase (GADA) and the protein tyrosine phosphatase-related molecule IA-2 (IA-2A), provides useful markers for diagnosis of type 1 diabetes. Over 80% of patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes have GADA, 70% have IA-2A and approximately 60% have IAA (1). However, a few cases have no evidence of β-cell autoimmunity despite absolute insulin deficiency, a form of the disease classified as idiopathic, non-immune mediated, type 1 diabetes (4, 5).

Numerous genetic studies have demonstrated associations of HLA class II variants with type 1 diabetes. In Caucasian populations, the DRB1*0405/*0401-DQB1*0302 and DRB1*0301-DQB1*0201 genotypes are positively correlated with type 1 diabetes, and the former genotype is significantly more strongly predisposing than the latter (6). In the Japanese population, however, the DRB1*0301-DQB1*0201 genotype is rare in both patients and the general population, whereas the DRB1*405-DQB1*0401 and DRB1*0901-DQB1*0303 genotypes are positively correlated with type 1 diabetes (7, 8). Moreover, Kawabata et al. (8) reported that the DRB1*405-DQB1*0401 genotype is more strongly associated with disease susceptibility than the DRB1*0901-DQB1*0303 genotype because the presence of the former genotype alone confers susceptibility to type 1 diabetes, whereas homozygous presence of the latter is only associated with development of the disease (8). Furthermore, Sugihara et al. (9) reported that the DRB1*0901-DQB1*0303 genotype induces stronger autoimmune destructive responses against β-cells than the DRB1*405-DQB1*0401 genotype in childhood-onset cases.

On the other hand, several studies have shown that the pathogenic characteristics in young children with type 1 diabetes differ from those in older children as well as adults. Several studies have reported decreased prevalences of some of the diabetes-related autoantibodies at diagnosis in young children compared with those in cases with later onset (10,11,12,13). In regard to genetic background, several studies have revealed different frequencies of some diabetes-related HLA alleles and haplotypes in young children compared with those in older children and adults (9, 10, 12, 14, 15).

These findings suggest that pathogenic characteristics in young children with type 1 diabetes could differ from those in older cases. However, little is known about the genetic background or β-cell autoimmunity status of young children with type 1 diabetes in Japan. We studied the pathogenic characteristics at diagnosis of Japanese children with type 1 diabetes presenting prior to 5 yr of age.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

The study subjects were 23 Japanese children, 9 males and 14 females, with type 1 diabetes residing in the Kanto district of Japan. They were diagnosed as having the disease prior to 5 (1.1–4.8) yr of age during the period from 1995 to 2005. They exhibited typical symptoms of diabetes, and 20 out of 23 (87.0%) presented with ketoacidosis (pH<7.3 and HCO3–<15.0 mmol/L) and/or impaired consciousness as the initial manifestation of the disease. The mean plasma glucose and HbA1c values at diagnosis were 556 ± 121 (362–784) mg/dl and 10.8 ± 2.2 (7.5–14.8) %, respectively. The mean serum C-peptide level was 0.25 ± 0.25 (undetectable-0.8) ng/ml at diagnosis. In regard to family history of diabetes, one patient had an affected father with type 1 diabetes, but none of the patients had any first-degree relatives with type 2 diabetes.

Methods

We evaluated the prevalence of GADA and IA-2A in 19 and 17 of the 23 young children, respectively, at the time of diagnosis and determined the HLA class II genes in all the subjects.

GADA and IA-2A were determined by radioimmunoassay (Cosmic Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The cut-off limits for GADA and IA-2A antibody positivity were 1.5 U/ml and 0.4 U/ml, respectively. The frequencies of these two antibodies were compared with the results for 51 children, 21 males and 30 females, with later onset of type 1 diabetes. These children also initially exhibited typical symptoms of hyperglycemia and/or presented with ketoacidosis, but they were more than 5 (7.1–14.8) yr of age at diagnosis.

HLA-DR and DQ genes were analyzed using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-sequencing-based typing (SBT) method [SRL, Inc., Tokyo, Japan] (16). Informed consent for analysis of HLA-DR and DQ genes was obtained from the patients’ parents. This study was approved by the ethical committee of our institution.

The frequencies of viral infections prior to the onset of diabetes was also investigated in all subjects. Preceding viral infection was estimated by the presence of symptoms such as pyrexia and sore throat more than 3 mo prior to the onset of diabetes and/or by elevation of IgM class antibody-titers against viruses in sera.

Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as means ± SD. To detect differences in frequencies between two groups, the chi-square test was applied, and p<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Prevalences of GADA and IA-2A at the time of diagnosis

We examined the prevalences of β-cell antibodies, GADA and IA-2A, at the time of diagnosis in children with type 1 diabetes who were younger than 5 years at diagnosis. The prevalence of GADA was 31.6% (6/19), and that of IA2-A was 47.1% (8/17). On the other hand, among the 51 children with later onset of type 1 diabetes diagnosed after 5 yr of age, the prevalence of GADA was 86.3% (44/51), and that of IA-2A was 82.5% (33/40). Thus, the prevalences of both GADA and IA-2A were significantly decreased in the young children compared with the children with later-onset (p<0.0001 and p=0.0064, respectively).

In respect to the titers of GADA and IA-2A, the mean titer of GADA was 9.62 ± 19.33 U/ml and that of IA-2A was 2.64 ± 4.13U/ml in the young children.

Frequencies of HLA class II alleles

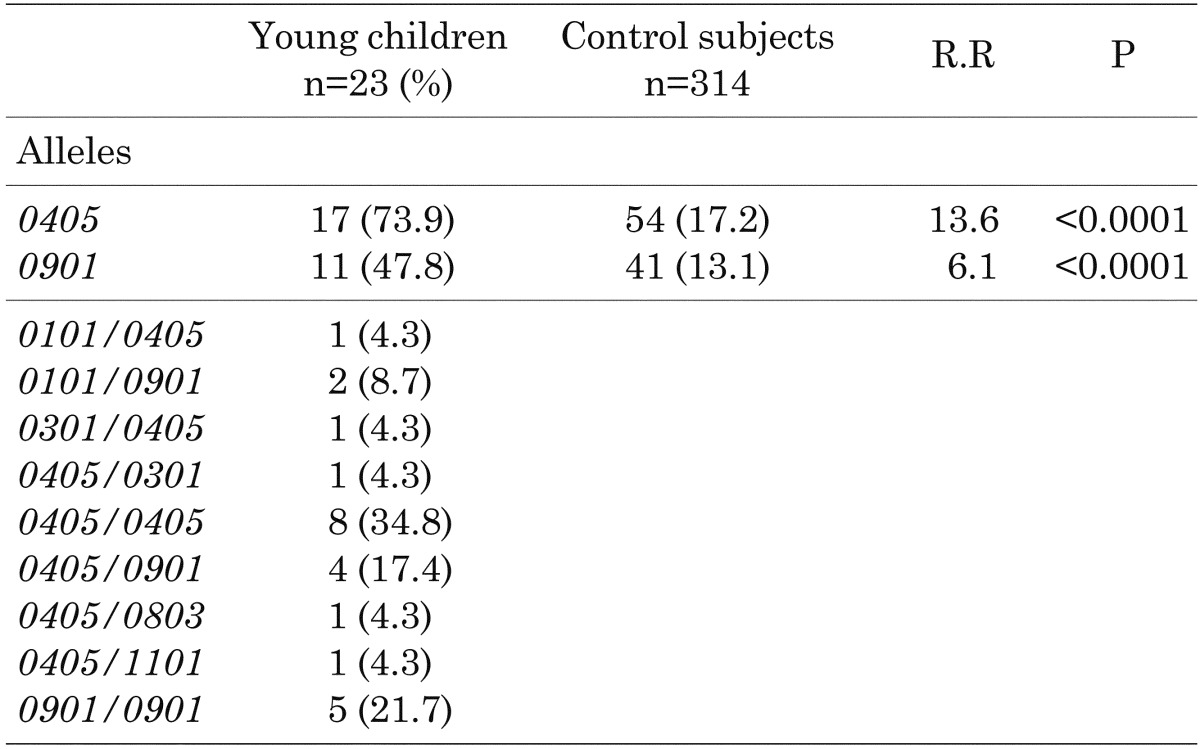

Frequencies of HLA-DRB1 alleles: Table 1 shows the frequencies of HLA-DRB1 alleles in the young children. The allele frequency of DRB1*0405 was 73.9%, and that of DRB1*0901 was 47.8%. The young children had significantly higher frequencies of DRB1*0405 (p<0.0001) and DRB1*0901 (p<0.0001) than the control subjects (8). Moreover, all subjects had one of the high-risk HLA-DRB1 alleles. On the other hand, the allele frequency of DRB1*0405/*0405 was 34.8%, that of DRB1*0405/*0901 was 17.4% and that of DRB1*0901/*0901 was 21.7%. These results demonstrated that homozygous or compound heterozygous presence of the high-risk HLA-DRB1 alleles was frequent in the young children. Furthermore, none of the patients had any protective HLA-DRB1 genotypes.

Table 1. Frequencies of HLA-DRB1 alleles in children with type 1 diabetes who were younger than 5 yr of age at diagnosis.

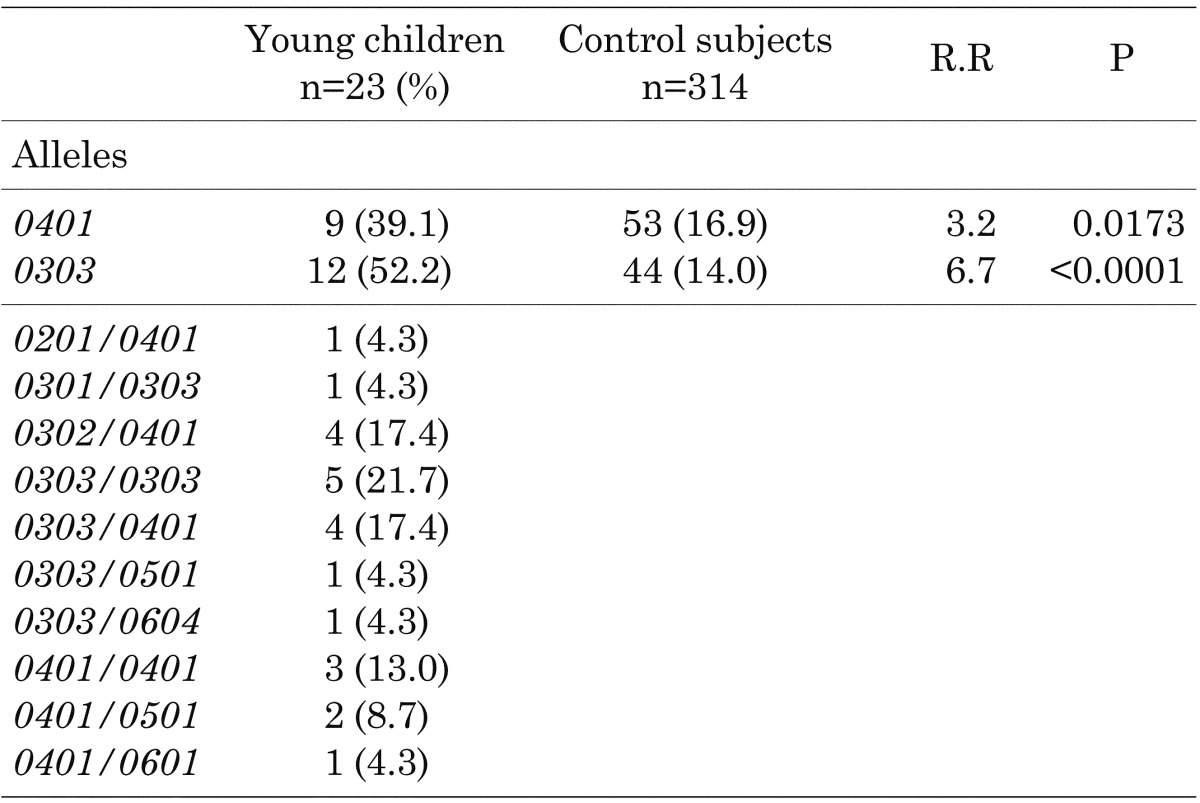

Frequencies of HLA-DQB1 alleles: Table 2 shows the frequencies HLA-DQB1 alleles in the young children. The allele frequency of DQB1*0401 was 39.1%, and that of DQB1*0303 was 52.2%. The young children had significantly higher frequencies of DQB1*0401 (p=0.0173) and DQB1*0303 (p<0.0001) than the control subjects (8). All subjects also had one of the high-risk HLA-DQB1 alleles. On the other hand, the allele frequency of DQB1*0303/*0303 was 21.7%, that of DQB1*0303/*0401 was 17.4% and that of DQB1*0401/*0401 was 13.0%. These results also demonstrated that homozygous or compound heterozygous presence of the high-risk HLA-DQB1 alleles was frequent in the young children. Similar to the results for the HLA-DRB1 alleles, none of the patients had any protective HLA-DQB1 genotypes.

Table 2. Frequencies of HLA-DQB1 alleles in children with type 1 diabetes who were younger than 5 yr of age at diagnosis.

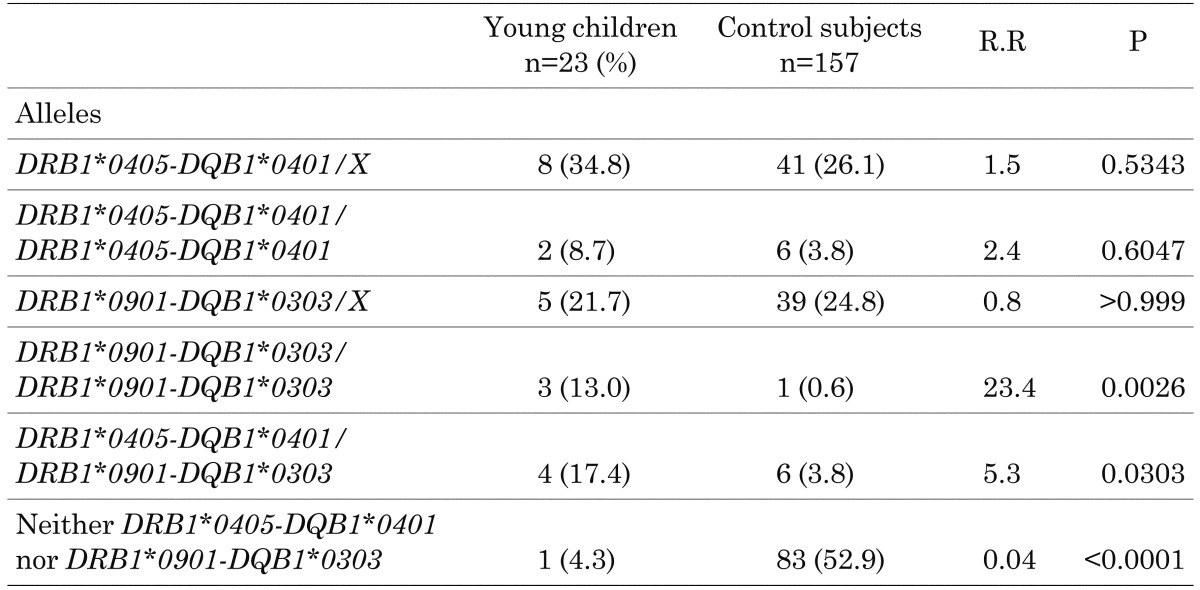

Frequencies of HLA-DRB1 and DQB1 haplotypes

Table 3 shows the frequencies HLA-DRB1 and DQB1 haplotypes in the young children. The frequency of homozygous or heterozygous presence of DRB1*0405-DQB1*0401 was 60.9%, and that of DRB1*0901/DQB1*0303 was 57.2%. The heterozygous frequencies of the presence of DRB1*0405-DQB1*0401 and DRB1*0901/DQB1*0303 were 34.8% and 21.7%, respectively, whereas the homozygous frequencies of these high-risk haplotypes were 8.7% and 13.0%, respectively. The young children had significantly higher frequencies of homozygous presence of DRB1*0901/DQB1*0303 (21.7%, p=0.0026) and genotypic combination of the two high risk alleles (p=0.0303) compared with the control subjects (8). Only one patient (4.3%) had neither of the high-risk haplotypes, which was significantly less frequent than in the control subjects (p<0.0001) (8).

Table 3. Frequencies of HLA-DQB1 and DQB1 haplotypes in children with type 1 diabetes who were younger than 5 yr of age at diagnosis.

Frequencies of viral infections prior to disease onset

We examined the frequencies of viral infections prior to the onset of diabetes. Ten of the 23 patients (43.5%) had symptoms of viral illness before more than 3 mo prior to the onset of diabetes and/or had elevated IgM class antibodies against viruses, i.e., three cases with influenza viruses, two cases with coxsackie B viruses, one case with a mumps virus, one case with a respiratory syncytial virus and four cases with unknown viral origins.

Discussion

The pathogenic characteristics of young children with type 1 diabetes could be different from those of older children as well as adults. Several studies have demonstrated lower prevalences of some diabetes-related autoantibodies in young-onset cases. Hathout et al. (10) reported that the prevalences of islet-cell antibodies (ICA) and GADA were decreased in young children diagnosed before 5 yr of age compared with those of older children. Feeney et al. (11) reported lower frequencies of GADA and IA-2A in young children diagnosed before 5 yr of age than in older children. Komulainen et al. (12) reported that very young children less than 2 yr of age had the lowest titers of IA-2A among pediatric cases with type 1 diabetes. In the present study, we found significantly lower prevalences of both GADA and IA-2A at diagnosis in young children presenting prior to 5 yr of age than in older cases. These findings indicate that the prevalences of GADA and IA-2A are possibly decreased in children diagnosed in early childhood.

Most studies on diabetes-related autoantibodies have shown a higher prevalence of IAA at diagnosis in young children than in adolescents and adults (11,12,13, 17, 18). The early appearance of IAA is usually followed by autoantibodies to other β-cell antigens such as GAD and IA-2 (17, 16). Unfortunately, we were unable to examine IAA because of technical difficulties with antibody measurement. It is probable that our subjects might have had a high frequency of IAA at diagnosis despite the low prevalences of GAD and IA-2A.

The absence of diabetes-related autoantibodies in these young children at the time of diagnosis suggests that mechanisms other than autoimmunity lead to destruction of pancreatic β-cells. One possible mechanism involves viral infections via a direct cytotoxic effect on β-cells. We found that viral infections prior to the onset of diabetes were frequent in young children. Hathout et al. (10) also reported a high frequency of preceding viral illness among children with young-onset diabetes. Several studies have shown that certain viruses are capable of inducing diabetes in experimental animals (1, 2). Another hypothesis involves rapid progression of β-cell autoimmunity in young-onset childhood diabetes. It is possible that immune-mediated β-cell destruction develops rapidly and that β-cell autoantibodies have already disappeared prior to clinical diagnosis. Consequently, we could not find diabetes-related autoantibodies in sera at the time of diagnosis.

Sugihara et al. (9) reported that that DRB1*0901-DQB1*0303 is more common in children with early-onset (0–5 yr of age) diabetes, whereas DRB1*405-DQB1*0401 is more frequently detected in late-onset cases (11–16 yr of age) among Japanese children with type 1 diabetes. Ohtsu et al. also (15) reported a higher frequency of DRB1*0901-DQB1*0303 in young-onset cases than in late-onset and slowly progressive cases. However, we found the prevalences of these two high-risk HLA class II genotypes, which were more frequent than those in the older cases, to be equal. Furthermore, no young children had any protective genotypes for either HLA-DR or -DQ alleles. From these findings, strong HLA-defined disease susceptibility may induce severe destruction of pancreatic β-cells early in life in patients with early-onset type 1 diabetes. Rapid autoimmune and/or non-immune mediated β-cell destruction develop prior to clinical diagnosis of the disease. However, the number of subjects used in the present study was too small to reach a conclusion. Other previous studies have demonstrated data that is different fro our results (9, 15). Father accumulation of data is required in regard to HLA genotypes and haplotypes in young children with type 1 diabetes in the Japanese population. Caucasian studies have demonstrated HLA genotypes associated with disease-susceptibility to be more frequent in young children, whereas the proportion of children carrying a genotype including protective alleles is higher among the older cases (10, 12).

In conclusion, the children diagnosed with type 1 diabetes before 5 yr of age had decreased prevalences of diabetes-related autoantibodies, but had high frequencies of viral infections prior to disease onset. Furthermore, strong disease susceptibility conferred by HLA class II genes was evident in these young children. Early-childhood onset cases may have diabetes-related autoimmunity and genetic backgrounds different from those of patients diagnosed at a later age.

References

- 1.Knip M. Etiopathogenic aspects of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes in childhood and adolescence. In: Chiarelli F, Dahl-Jorgensen K, Keiss W, editors. Pediatr Adolesc Med 10 Basel: Karger; 2005. p.1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akerblom HK, Knip M. Putative environmental factors in type 1 diabetes. Diabet Metab Rev 1998;11: 37–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilkin TJ. The accelerator hypothesis: weight gain as the missing link between Type I and II diabetes. Diabetologia 1996;44: 914–22 doi: 10.1007/s001250100548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes MellitusReport of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 1998;21(Suppl 1): 5–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alberti KGMM, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Provision report of a WHO Consultation. Diabet Med 1998;15: 539–53 doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cucca F, Lampis R, Congia M, Angius E, Nutland S, Bain SC, et al. A correlation between the relative predisposition of MHC class II alleles to type 1 diabetes and the structure of their proteins. Hum Mol Genet 2001;10: 2025–37 doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.19.2025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Awata T, Kuzuya T, Matsuda A, Iwamoto Y, Kanazawa Y. Genetic analysis of HLA class II alleles and susceptibility to type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus in Japanese subjects. Diabetologia 1992;35: 419–24 doi: 10.1007/BF02342437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawabata Y, Ikegami H, Kawaguchi Y, Fujisawa T, Shintani M, Ono M, et al. Asian-specific HLA haplotypes reveal heterogeneity of the contribution of HLA-DR and -DQ haplotypes to susceptibility to type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2002;51: 545–51 doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2.545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugihara S, Sakamaki T, Konda S, Murata A, Wataki K, Kobayashi Y, et al. Association of HLA-DR, DQ genotype with different β-cell functions at IDDM diagnosis in Japanese children. Diabetes 1997;46: 1893–7 doi: 10.2337/diab.46.11.1893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hathout EH, Hartwick N, Fagoaga OR, Colacino AR, Sharkey J, Racine M, et al. Clinical, autoimmune, and HLA characteristics of children diagnosed with type 1 diabetes before 5 years of age. Pediatrics 2003;111: 860–3 doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feeney SJ, Myers MA, Mackay IR, Zimmet PZ, Howard N, Verge C, et al. Evaluation of ICA-512As in combination with other islet cell antoantibodies at the onset of IDDM. Diabetes Care 1997;20: 1403–7 doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.9.1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Komulainen J, Kulmara P, Savola K, Lounamaa R, Ilonen J, Reijonen H, et al. Clinical, autoimmune, and genetic characteristics of very young children with type 1 diabetes. Childhood Diabetes in Finland (DiMe) Study Group. Diabetes Care 1999;22: 1950–5 doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.12.1950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yokota I, Matsuda J, Naito E, Ito M, Shima K, Kuroda Y. Comparison of GAD and ICA512/IA-2 antibodies at and after the onset of IDDM. Diabetes Care 1998;21: 49–52 doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.1.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murao S, Makino H, Kaino Y, Konoue E, Ohashi J, Kida K, et al. Differences in the contribution of HLA-DR and -DQ haplotypes to susceptibility to adult- and childhood-onset type 1 diabetes in Japanese patients. Diabetes 2004;53: 2684–90 doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.10.2684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohtsu S, Takubo N, Kazahari M, Nomoto K, Yokota F, Kikuchi N, et al. Slowly progressing form of type 1 diabetes mellitus in children: genetic analysis compared with other forms of diabetes mellitus in Japan. Pediatr Diabet 2005;6: 221–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-543X.2005.00133.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steven GE, Bodmer M, Bodmer JG. HLA class II region nucleotide sequence. Tissue Antigens 1995;45: 258–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vardi P, Ziegler AG, Matthews JH, Diub S, Keller RJ, Ricker AT, et al. Concentration of insulin autoantibodies at onset of type I diabetes. Inverse log-linear correlation with age. Diabetes Care 1998;11: 736–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ziegler AG, Hummel M, Schenker M, Bonifacio E. Autoantibody appearance and risk for development of childhood diabetes in offspring of parents with type 1 diabetes: The 2-year analysis of the German BABYDIAB Study. Diabetes 1998;48: 460–8 doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.3.460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]