Abstract

Background

At 360 000 cases annually, heart failure is the most common main diagnosis in adults in German hospitals. Treating heart failure is expensive. This study tested whether patients in the case management program (CMP) “CorBene—Better Care for Patients With Heart Failure” have a lower mortality rate and lower hospital admission and readmission rates than patients receiving regular management.

Methods

Routine data from a large German statutory health insurance company were analyzed. After propensity score matching, a total of 1202 patients (intervention group versus control group) were studied in relation to the endpoint “hospital admission and readmission rate” and the variables “annual physician contact rate,” “mortality,” and “inpatient treatment costs.”

Results

The intervention group showed a lower rate of hospital admission/readmission (6.2%/18.9% versus 16.6%/36.0%; p<0.0001 / p = 0.041). Mortality rates did not differ significantly (5.0% versus 6.7%; p = 0.217). Analysis of hospital admission data showed no significant differences between the groups in terms of length of hospital stay or costs for heart failure–related treatment per hospital stay. However, the average annual costs for inpatient treatment in the CMP group, at €222.22 per patient, were 67.5% lower than the equivalent costs in the control group (€683.88) (p<0.0001).

Conclusion

Fewer patients in the intervention group were admitted and readmitted to hospital, and lower inpatient treatment costs were identified. The physician contact rate was higher than in the control group.

As a result of the aging population and medical advances resulting in falling mortality for ischemic heart diseases, the incidence of heart failure is likely to continue to increase in the years to come. This will pose a challenge to both funders and service providers (1, 2). The rate of new cases of heart failure is 10 per 1000 individuals aged over 65 years (3). In addition to considerable morbidity, heart failure is also associated with an unfavorable prognosis and thus high disease-related mortality. Overall, 52.3% of all heart failure patients die within five years of their initial diagnosis (3). Heart failure is a major disease in Germany and is the third most common cause of death, accounting for around 49 000 cases in 2008 (4). In 2009 it was also—aside from normal newborns—the most common main diagnosis in German hospitals (363 700 cases) (ICD-10 I50) (5). Furthermore, disease progression is characterized by frequent hospital readmissions: 23% of hospitalized patients are readmitted as inpatients within 30 days of their first hospital stay, and the six-month hospital readmission rate is as high as 44 to 50% (6– 8). The direct costs of heart failure in Germany have risen constantly in recent years and in 2008 reached the record sum of €3.2 billion, which was 1.2% of all Germany’s health care expenditure. Approximately 45% (€1.45 billion) of disease costs are inpatient hospital care costs (9).

This study shows that a case management program for heart failure patients can reduce the number of hospital stays and readmissions. This can also lead to savings in inpatient treatment costs. The study also analyzed the extent to which participation in a case management program affects mortality.

Clinical heterogeneity (e.g. of the primary data on the study groups) is a significant variable in clinical field studies in particular. According to Gartlehner et al. (10), the patient-related heterogeneity of a clinical picture can lead to variation in the results obtained and to statistical heterogeneity. This effect can be greater than the estimated random error (10). The CorBene field data provides information on the medical care of heart failure patients who receive routine treatment in cardiology and primary-care practices. This means that in the future patient-related medical data from routine care will have to be matched with pseudonymized data of individuals with statutory health insurance. This will make it possible to investigate data on routine care continually. Data quality poses a particular challenge in this context, in terms of completeness and plausibility of content.

Patients, methods

Study design

This study analyzed routine data from a large German statutory health insurer for the years 2005 to 2009. Because patients were recruited (with no randomization) from routine care, the study can be considered a field study. This means that the profile of the recruited patients is very similar to that of heart failure patients in a medical practice, which means there is also a certain amount of heterogeneity between the patients recruited in this study. Propensity score matching was used to develop and implement a control group design. We compared the data of heart failure patients receiving statutory routine treatment in Germany (the control group) to the data of case management program patients (the intervention group). Predefined criteria for participation in the clinical case management program were checked by the treating cardiologist before patients were included in the program. The control group was formed retrospectively using routine data from the statutory insurer. This meant that the inclusion criteria for the control group and the intervention group differed slightly; this is, however, typical for health-care research. In addition to patient data and financial data, the evaluation also included information on medical care provided, mortality, and drug treatment. No sociodemographic information or data on comorbidities could be obtained from the routine data supplied by the statutory health insurer. The results of drug analyses are to be published in a separate article.

Study population

The sample for our study consists of heart failure patients of all ages who had continuous insurance coverage with the largest statutory health insurer (of those that took part in the case management program as contract partners) from July 1, 2005 to December 31, 2009. There are two groups of patients:

The CMP (case management program) group (n = 1000): All patients with continuous insurance coverage throughout the observation period who were entered in the case management program by their cardiologist (and were therefore case management program participants) were allocated to the intervention group. Patients’ participation in the case management program was voluntary. The following inclusion criteria were binding:

Clinical symptoms of heart failure according to the NYHA Classification (Box) (11)

Evidence of ventricular dysfunction

Confirmed diagnosis of heart failure (“confirmed diagnosis”) coded as part of standard care (“routine care”) within the German statutory health care system.

Box. New York Heart Association (NYHA) Classification (11).

The NYHA Classification is an established system for classifying heart failure according to four classes. This is based on the patient’s symptoms and ability to undertake physical activity.

-

NYHA Class I

Patients with cardiac disease but resulting in no limitation of physical activity. Ordinary physical activity does not cause undue fatigue, palpitation, dyspnea or anginal pain.

-

NYHA Class II

Patients with cardiac disease resulting in slight limitation of physical activity. They are comfortable at rest. Ordinary physical activity results in fatigue, palpitation, dyspnea or anginal pain.

-

NYHA Class III

Patients with cardiac disease resulting in marked limitation of physical activity. They are comfortable at rest. Less than ordinary activity causes fatigue, palpitation, dyspnea or anginal pain.

-

NYHA Class IV

Patients with cardiac disease resulting in inability to carry on any physical activity without discomfort. Symptoms of heart failure or the anginal syndrome may be present even at rest. If any physical activity is undertaken, discomfort increases.

Patients who did not meet these inclusion criteria could not be included in the case management program. Patients who took part in the case management program for less than six months were excluded due to lack of sufficient data.

The non-CMP group (n = 9626): The control group (non-CMP group) consists of patients with a confirmed diagnosis of heart failure within German routine care. The inclusion criteria for the control group were as follows:

Continuous health insurance coverage throughout the observation period

Not a case management program participant

Confirmed diagnosis of heart failure (ICD-10 150) coded according to the NYHA Classification as part of routine care in Germany in the first two quarters of 2005.

Matching procedure, statistical analysis

Propensity score matching was used to guarantee that the patient groups were comparable (12). In order to minimize selection effects and to eliminate confounding factors, the propensity score was stated using stepwise logistic regression with the independent variables age, sex, and NYHA stage as indicated by the fifth character of the ICD code.

After cases for which no statistical match could be found had been excluded, the final intervention and control groups each contained 601 patients. Survival curves were drawn using the Kaplan–Meier method; differences between patients in the intervention and control groups were analyzed using the log-rank test. The observation period began on July 1, 2005 and lasted a total of 54 months. Statistical tests were performed using the statistics program IBM SSPS Statistics (version 19).

Hypotheses

The central hypothesis of this study is that participation in the case management program reduces the number of hospital stays and the hospital readmission rate among heart failure patients, resulting in cost savings when compared to routine care. Evaluation of admission data included cases in which heart failure was coded as the main diagnosis at the time of discharge from the hospital. The following variables were also investigated: mortality rate, contact with a physician (primary care physician, cardiologist) as part of outpatient care, and disease-related costs of inpatient care borne by health insurers.

Main features of the case management program

The CorBene case management program was developed in 2005 and consists of the following:

Use of drug treatment in line with guidelines on the basis of a predefined positive list (including drug interactions) that serves as a binding guideline for all participating physicians

Early integration of the specialist physician (cardiologist) and guaranteed appointment with a specialist physician within 10 days of initial inclusion in the program

Cardiology monitoring examinations performed at prescribed intervals (no limitation on specialized medical care)

Remote care prescribed, and remote monitoring used.

The aim of the CorBene program is to improve care of heart failure patients and at the same time to guarantee high-quality medical treatment and optimized use of resources. Close cooperation between the various service providers and the mandatory documentation in the form of evaluation questionnaires guarantee an ongoing exchange of information between cardiologist and primary care physician and should also prevent unnecessary duplicate examinations. A treatment plan in compliance with guidelines ensures that case management program participants are treated in line with the findings of the latest scientific and medical research. Following five years’ development, CorBene is now the largest nationwide case management program in Germany (with around 4300 patients and 95 participating statutory health insurers). It is ongoing.

Results

Primary patient data

The established variables for a total of 1202 patients were included in the evaluation. Table 1 shows the primary data for the sample as a whole.

Table 1. Primary data of study groups.

| Parameter | Intervention group (n = 601) | Control group (n = 601) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at reference time, mean (SD) [95% CI] |

71.7 (±8.7) [71.0; 72.4] |

72.2 (±9.0) [71.5; 72.9] |

0.279*1 |

| Male patients, % (n) [95% CI] |

65.4 (393) [61.2; 69.2] |

64.1 (385) [59.8; 67.7] |

0.629*2 |

| NYHA functional status, mean (SD) [95% CI] |

2.16 (±0.6) [2.11; 2.20] |

2.17 (±0.7) [2.11; 2.22] |

0.619*1 |

| Heart failure class, % (n) | 0.761*2 | ||

| NYHA I | 9.5 (57) | 15.3 (92) | |

| NYHA II | 67.7 (407) | 55.2 (332) | |

| NYHA III | 20.3 (122) | 26.6 (160) | |

| NYHA IV | 2.5 (15) | 2.8 (17) | |

*1t-test for independent samples; *2chi-square test; NYHA: New York Heart Association

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; mean: arithmetic mean; SD: standard deviation; n: number of patients

Hospital admission data

Table 2 shows the results of analysis of hospital admission data. While 6.2% of patients in the intervention group received inpatient treatment for the main diagnosis heart failure, the corresponding figure for the control group was 16.6% (p<0.0001). In order to assess a potential effect of the slight difference in NYHA Classification distribution between the control and intervention groups, hospital admission data was also clustered by NYHA stage. Higher heart failure-related hospital admission rates were reported in the control group than in the intervention group for all NYHA stages (Figure 1). Analysis of hospital readmission data (repeat inpatient admission for heart failure following an initial hospital stay) also shows differences between the groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Results obtained from data on hospital admissions.

| Parameter | Intervention group | Control Dgroup | Difference (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital admission rate, % (n) [95% CI] |

6.2 (37) [4.4; 8.2] |

16.6 (100) [13.5; 19.8] |

–10.4 | <0.0001* |

| Hospital readmission rate, % (n) [95% CI] |

18.9 (36) [6.9; 33.3] |

36.0 (7) [27.3; 44.8] |

–17.1 | 0.0411* |

*Fisher’s exact test; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; n: number of patients

Figure 1.

Hospital admission rate by NYHA class

*p = nonsignificant; **p<0.05 (Fisher’s exact test)

Contact with physicians, mortality rate

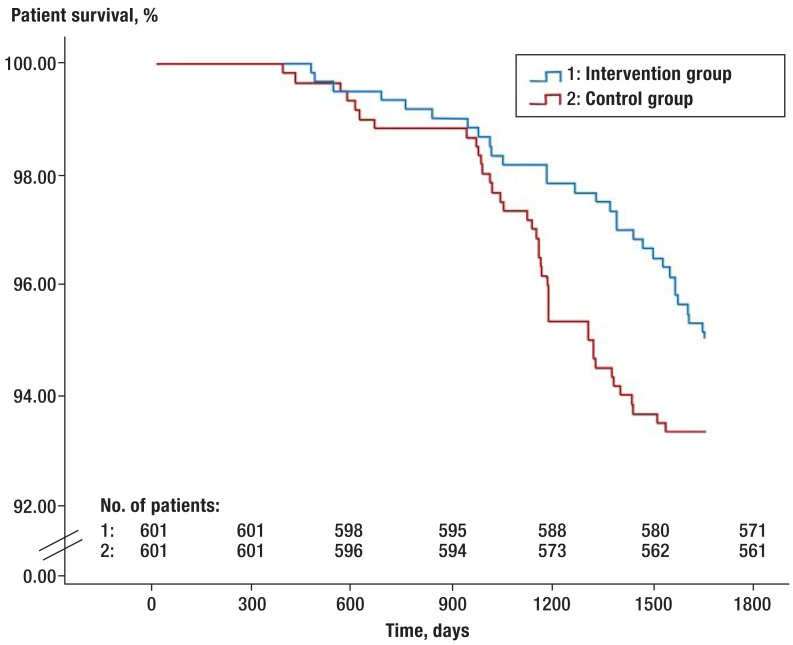

A further criterion in our study was how frequently patients received outpatient medical care for their heart failure from their treating primary care physician or cardiologist. The results show a mean of 2.2 (SD ± 2.2) (95% CI: 2.0 to 2.4) contacts with a physician per year in the intervention group, and 1.8 (SD ± 2.0) (95% CI: 1.6 to 2.0) in the control group (Mann–Whitney U-test, p = 0.001). Figure 2 shows the survival data for the patients in both groups (Kaplan–Meier curve). Total mortality (death from any cause) in the groups of matched pairs was 5.0% in the intervention group (95% CI: 3.4 to 6.7) and 6.7% in the control group (log-rank test, p = 0.217).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of matched pairs

Treatment costs

Analysis of hospital stay duration shows no significant difference between the intervention and control groups (9.74 days [95% CI: 8.3 to 11.3] versus 10.00 days [95% CI: 8.7 to 11.5]) (Mann–Whitney U-test, p = 0.804). The results also show no significant difference in the mean cost per heart failure-related hospital stay, with a mean of €2841.59 (SD ± 766.04) (95% CI: 2627.51 to 3076.12) in the intervention group and €2651.71 (SD ± 1229.61) [95% CI: 2476.87 to 2845.63] in the control group (Mann–Whitney U-test, p = 0.205). However, the annual heart failure-related hospitalization costs per patient were €222.22 (95% CI: 145.10 to 307.77) in the intervention group versus €683.88 (95% CI: 522.33 to 850.70) in the control group (Mann–Whitney U-test, p <0.0001). For every case management program participant, the health insurer therefore achieved a mean annual saving of €461.66 when compared to a patient receiving routine care. Because data on outpatient treatment costs was not available, total costs could not be included in the analyses.

Discussion

As a result of demographic changes, the number of heart failure patients will continue to rise. In the context of the associated increase in scarcity of resources, case management programs are gaining more and more public interest for the treatment of chronic diseases. In this study we investigated the effect of a case management program for heart failure patients on hospital admission and inpatient readmissions, in addition to mortality, the rate of contact with physicians, and the associated disease-related inpatient treatment costs, versus patients receiving routine care. The results show that the hospital admission rate was successfully reduced in chronic heart failure patients whose treatment was based on the named components of the case management program. This achieved both added value for patients and a positive effect on the cost efficiency of treatment. It became clear that participation in a case management program could reduce the rate of hospital admissions by 10.4%. Hospital readmissions were reduced by 17.1% when compared to routine care. These figures are in line with the results of Rich et al., who in their own study reported a 13% reduction in hospital readmissions of heart failure patients (13). According to a systematic review performed by Rich, which included a total of 16 studies on “heart failure disease management programs,” all the included studies demonstrated substantial successes in areas such as reducing hospital admissions (14). While Disher et al. determined that the mean hospital stay duration of case management program participants was 3.9 days, i.e. a mean of 2.1 days shorter than those of nonparticipants (15), the present study was unable to confirm this finding. In view of the lower hospital admission and readmission rates, case management program participation leads to an effective annual cost saving of €461.66 per patient when compared to hospitalization costs for patients receiving routine care. Although Galbreath et al. did not describe a cost advantage for heart failure case management programs in their study (16), the results of our study are in line with those of many comparable studies (17– 20). The conclusion can therefore be drawn that case management programs lead to cost savings and qualitative improvement. Expert discussions should therefore concentrate more on case management programs for major chronic diseases.

Limitations

At the beginning of the observation period it was not known for how long any insured individual had been suffering from heart failure. A further limitation is the limited length of the study’s observation period. This may lead to hospital admissions after the end of observation being overlooked. In addition, patients whose participation in the case management program lasted less than six months had to be excluded from the analysis on the grounds of insufficient data, because they might otherwise have distorted the findings. It must also be pointed out that our study involved nonrandomized propensity score matched analysis of routine data obtained from a German statutory health insurer. Because participation was voluntary, neither physicians nor patients could be allocated to the study groups at random. No sociodemographic data or data on comorbidities could be included in matching because the health insurer was unable to provide the appropriate information. Selection bias within the study cannot be completely ruled out (for instance, case management program participants may also be more aware of their health or more likely to behave cooperatively). As only routine data was available, and therefore no information on cause of death could be consulted, evaluation of mortality rates could only take into account overall mortality. Although routine data analyses are highly relevant (because they portray medical care actually provided in Germany), this type of study is still very rare, although these very findings provide added value for health-care research. A further potential limitation of this study is the questionable extent to which the study population is representative of the German population, as all the patients were insured by the same health insurer. In addition, only patients who had continuous insurance coverage throughout the observation period were included in the study. Regarding the analyzed effect sizes, we estimate that the differences made by the case management program will become even more significant, because some of the analyzed effects take longer to manifest.

Key Messages.

A case management program for heart failure patients was compared with routine care. Propensity score matching was performed on the basis of routine data obtained from a large health insurer.

601 heart failure patients each were recruited to the intervention and control groups.

There were fewer hospital admissions and readmissions in the intervention group than in the control group (6.2% and 18.9% respectively versus 16.6% and 36.0% respectively; p <0.0001, p = 0.04).

The mean annual cost per patient in the case management program group was €222.22, 67.5% less than in the control group (€683.88) (p <0.0001).

There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of mortality or length or cost of heart failure–related hospital stay.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Caroline Devitt, M.A.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The data collection and analysis expenses of the Institute for Health Economics and Health-Care Research (Institut für Medizin-Ökonomie & Medizinische Versorgungsforschung) at the University of Applied Sciences, Cologne, which was entrusted with the scientific support of the CorBene Program, were reimbursed by the participating company health insurers.

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones DM, Larson MG, Leip EP, et al. Lifetime risk for developing congestive heart failure: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2002;106:3068–3072. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000039105.49749.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cleland JGF, Khand A, Clark A. The heart failure epidemic: exactly how big is it? Eur Heart J. 2001;22:623–626. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2009 update: A report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. American Heart Association. 2009;119:e21–e181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Statistisches Bundesamt. Todesursachen in Deutschland 2009. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt; 2010. Gesundheit. Fachserie 12 Reihe 4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Statistisches Bundesamt. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt 2011; Gesundheit Diagnosedaten der Patienten und Patientinnen in Krankenhäusern (einschließlich Sterbe- und Stundenfälle) Fachserie 12 Reihe 6.2.1. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross JS, Chen J, Lin Z, et al. Recent national trends in readmission rates after heart failure hospitalization. Circulation. 2010;3:97–103. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.885210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krumholz HM, Parent EM, Tu N, et al. Readmission after hospitalization for congestive heart failure among medicare beneficiaries. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aghababian RV. Acutely decompensated heart failure: opportunities to improve care and outcomes in the emergency department. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2003;3:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Statistisches Bundesamt. www.gbe-bund.de. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt; 2010. Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes: Krankheitskostenrechnung für die Jahre 2002 bis 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gartlehner G, West SL, Mansfield AJ, et al. Clinical heterogeneity in systematic reviews and health technology assessments: synthesis of guidance documents and the literature. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;28:36–43. doi: 10.1017/S0266462311000687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickstein K, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Failure. 2008;10:933–989. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, Leven CL, Freedland KE, Carney RM. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1190–1195. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rich MW. Heart failure disease management: a critical review. J Card Fail. 1999;5:64–75. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9164(99)90026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Discher CL, Klein D, Pierce L, Levine AB, Levine TB. Heart failure disease management: impact on hospital care, length of stay, and reimbursement. Congestive Heart Failure. 2003;9:77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2003.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galbreath AD, Krasuski RA, Smith B, et al. Long-Term healthcare and cost outcomes of disease management in a large, randomized, community-based population with heart failure. Circulation. 2004;110:3518–3526. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148957.62328.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kornowski R, Zeeli D, Averbuch M, et al. Intensive home-care surveillance prevents hospitalization and improves morbidity rates among elderly patients with severe congestive heart failure. Am Heart J. 1995;129:762–766. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hershberger RE, Ni H, Naumann DJ, et al. Prospective evaluation of an outpatient heart failure managment programm. J Card Fail. 2001;7:64–74. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2001.21677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.West JA, Miller NH, Parker KM, et al. A comprehensive management system for heart failure improves clinical outcomes and reduces medical resource utilization. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:58–63. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00676-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cline CMJ, Istraelsson BYA, Willenheimer RB, Broms K, Erhardt LR. Cost effective management programme for heart failures reduces hospitalisation. Heart. 1998;80:442–446. doi: 10.1136/hrt.80.5.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]