Abstract

Background

Nausea, retching and vomiting are very commonly experienced by women in early pregnancy. There are considerable physical and psychological effects on women who experience these symptoms. This is an update of a review of interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy previously published in 2003.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and safety of all interventions for nausea, vomiting and retching in early pregnancy, up to 20 weeks’ gestation.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (28 May 2010).

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials of any intervention for nausea, vomiting and retching in early pregnancy. We excluded trials of interventions for hyperemesis gravidarum which are covered by another review. We also excluded quasi-randomised trials and trials using a crossover design.

Data collection and analysis

Four review authors, in pairs, reviewed the eligibility of trials and independently evaluated the risk of bias and extracted the data for included trials.

Main results

Twenty-seven trials, with 4041 women, met the inclusion criteria. These trials covered many interventions, including acupressure, acustimulation, acupuncture, ginger, vitamin B6 and several antiemetic drugs. We identified no studies of dietary or other lifestyle interventions. Evidence regarding the effectiveness of P6 acupressure, auricular (ear) acupressure and acustimulation of the P6 point was limited. Acupuncture (P6 or traditional) showed no significant benefit to women in pregnancy. The use of ginger products may be helpful to women, but the evidence of effectiveness was limited and not consistent. There was only limited evidence from trials to support the use of pharmacological agents including vitamin B6, and anti-emetic drugs to relieve mild or moderate nausea and vomiting. There was little information on maternal and fetal adverse outcomes and on psychological, social or economic outcomes. We were unable to pool findings from studies for most outcomes due to heterogeneity in study participants, interventions, comparison groups, and outcomes measured or reported. The methodological quality of the included studies was mixed.

Authors’ conclusions

Given the high prevalence of nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy, health professionals need to provide clear guidance to women, based on systematically reviewed evidence. There is a lack of high-quality evidence to support that advice. The difficulties in interpreting the results of the studies included in this review highlight the need for specific, consistent and clearly justified outcomes and approaches to measurement in research studies.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Acupuncture Therapy [methods], Antiemetics [therapeutic use], Ginger [chemistry], Morning Sickness [etiology; therapy], Nausea [etiology; *therapy], Phytotherapy [methods], Pregnancy Complications [*therapy], Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Treatment Outcome, Vitamin B 6 [therapeutic use], Vitamin B Complex [therapeutic use], Vomiting [etiology; *therapy]

MeSH check words: Female, Humans, Pregnancy

BACKGROUND

Nausea and vomiting are commonly experienced by women in early pregnancy. Prevalence rates of between 50% and 80% are reported for nausea, and rates of 50% for vomiting and retching (Miller 2002; Woolhouse 2006). Retching (or dry heaving, without expulsion of the stomach’s contents) has been described as a distinct symptom that is increasingly measured separately to vomiting and nausea (Lacasse 2008; O’Brien 1996; Zhou 2001).

The misnomer ‘morning sickness’, which is colloquially used to describe nausea, vomiting and retching of pregnancy, belies the fact that symptoms can occur at any time of the day. Pregnant women experience nausea, vomiting and retching mostly in the first trimester, between six and 12 weeks, but this can continue to 20 weeks and persists after this time for up to 20% of women (Jewell 2003; Miller 2002).

Hyperemesis gravidarum, which is characterised by severe and persistent vomiting, is less common, affecting between 0.30% and 3% of pregnant women (Eliakim 2000; Jewell 2003; Miller 2002). Hyperemesis gravidarum is defined in different ways, though a widely used definition describes it as “intractable vomiting associated with weight loss of more than 5% of prepregnancy weight, dehydration and electrolyte imbalances which may lead to hospitalization” (Miller 2002). Ketosis is also commonly included as a consequence of hyperemesis gravidarum (Kousen 1993; Quinlan 2003). Including inpatient hospitalisation in the definition of hyperemesis gravidarum is problematic (Swallow 2002) as some instances may be alleviated or controlled by outpatient interventions (Bsat 2003). Within the operational definitions of hyperemesis gravidarum, there is generally a focus on the effects of the vomiting (dehydration, ketosis, weight loss). The lack of a standard definition has implications for the measurement of outcomes in controlled studies.

It is important to exclude pathological causes of nausea and vomiting before concluding that this is specific to pregnancy. Pregnant women being treated for nausea, vomiting and retching of pregnancy should have the other pathological causes of nausea and vomiting (such as peptic ulcers, cholecystitis, gastroenteritis, appendicitis, hepatitis, genito-urinary (e.g. pyelonephritis), metabolic and neurological disorders) considered and excluded before a diagnosis of nausea, vomiting and retching of pregnancy is given (Davis 2004; Koch 2002; Quinlan 2003).

Thought to be associated with rising levels of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) or estrogens, the causes of nausea, vomiting and retching of pregnancy remain unknown (Goodwin 2002). Vestibular, gastrointestinal, olfactory and behavioural factors may influence the woman’s response to the hormonal changes (Goodwin 2002). Social, psychological and cultural influencing factors have also been studied (Buckwalter 2002; O’Brien 1999). The number of previous pregnancies and the number of fetuses both seem to affect the risk of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (Einarson 2007; Louik 2006). Conditions with higher levels of hCG (multiple pregnancies and molar pregnancies (hydatidiform mole)) have been associated with more prevalent and more severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Based on observational studies, nausea, vomiting and retching in the first trimester were thought to be associated with a decreased risk of miscarriage, preterm delivery, low birthweight, stillbirth and fetal and perinatal mortality (Czeizel 2004; Weigel 1989) although a later study challenged these claims (Louik 2006).

There are considerable physical and psychological effects on women who experience these symptoms, with altered family, social or occupational functioning (Attard 2002; Chou 2003; Chou 2008; O’Brien 1992; O’Brien 1997; Swallow 2004). Nausea and vomiting affect women’s daily activities and their relationships (Atanackovic 2001; Attard 2002; Magee 2002b). The distress and functional limitations caused by nausea without vomiting are increasingly acknowledged (Davis 2004). Women have reported that they would like their symptoms and ensuing distress acknowledged to a greater degree by health professionals (Locock 2008). Studies have also highlighted the economic burden on women and society, mainly due to lost productivity and healthcare costs (Attard 2002; Piwko 2007).

Women are commonly offered advice about the (usually) self-limiting nature of the condition and advised to avoid foods, smells, activities or situations that they find nauseating and to eat small frequent meals of dry, bland foodstuffs (Davis 2004; Ornstein 1995). Many remedies are suggested for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy, including pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical interventions.

Pharmaceutical treatments include anticholinergics, antihistamines, dopamine antagonists, vitamins (B6 and B12), H3 antagonists or combinations of these substances (Koren 2002a; Kousen 1993; Magee 2002a; Quinlan 2003). The teratogenic effects (ability to disturb the growth or development of the embryo or fetus) of pharmaceutical medications (such as thalidomide) used in the past to control these symptoms have led to caution about prescribing and taking medications in the first trimester. This has led to the under-use of drugs that have been found to be safe and effective, for example, Bendecitin/Diclectin (doxylamine and pyridoxine) (Koren 2002a; Ornstein 1995). This drug was withdrawn from the US market because of the legal costs associated with its defence, despite its record of safety and a lack of legal rulings against it (Brent 2002; Koren 2002a; Ornstein 1995).

Because of concern about pharmaceuticals in early pregnancy and the general rise in the use of complementary and alternative therapies, non-pharmaceutical treatments are increasingly used to treat nausea and vomiting in pregnancy, because they may be perceived as ‘natural’ and therefore safe or lower risk than medications. These include herbal remedies (ginger, chamomile, peppermint, raspberry leaf), acupressure, acustimulation bands and acupuncture, relaxation, autogenic feedback training, homeopathic remedies (nux vomica, pulsatilla), massage, hypnotherapy, dietary interventions, activity interventions, emotional support, psychological interventions and behavioural interventions/modifications (Aikins Murphy 1998; Davis 2004; Jewell 2003; Niebyl 2002; Wilkinson 2000).

Studies report that healthcare professionals frequently recommend non-pharmaceutical treatments (Bayles 2007; Westfall 2004) and women frequently use them (Ernst 2002b; Tiran 2002). Alongside this growth in their use, there are concerns about the efficacy and safety of non-pharmaceutical treatments (Ernst 2002a; Ernst 2002b; Tiran 2002; Tiran 2003), as they are less rigorously regulated than pharmaceutical remedies. In addition, women and professionals are more likely to underestimate their possible risks (Tiran 2002; Tiran 2003).

OBJECTIVES

To assess the effectiveness and safety of all interventions for nausea, vomiting and retching in early pregnancy, up to 20 weeks’ gestation.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomised controlled trials of any intervention for nausea, vomiting and retching in early pregnancy. However, we excluded trials of interventions for hyperemesis gravidarum, which are being covered by another Cochrane review, the protocol for which is currently being prepared. We have not included quasi-randomised trials and trials using a crossover design. We have included studies reported in abstracts only, provided that there was sufficient information in the abstract, or available from the author, to allow us to assess eligibility and risk of bias.

Types of participants

Women experiencing nausea, vomiting and/or retching in pregnancy (but not hyperemesis gravidarum), where recruitment to a trial took place up to 20 weeks’ gestation.

Types of interventions

We included all interventions for nausea, vomiting and/or retching.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Symptomatic relief

Reduction or cessation in nausea, vomiting and/or retching. We examined outcomes measured by all commonly used instruments, including the following.

Pregnancy-Unique Quantification of Emesis and Nausea (PUQE), comprising three subscales covering nausea, vomiting and retching during the past 12 hours, measured using a five-point Likert scale; possible range three to 15, representing no symptoms to maximal symptoms; the cut-off point for severe symptoms is 13. This scale was developed by clinician-researchers at the Canadian Motherisk Program (Koren 2002a) studying nausea and vomiting in pregnancy and validated using the Rhodes Index (see next paragraph) and independent variables (Koren 2002b; Koren 2005; Lacasse 2008).

The Rhodes Index of Nausea, Vomiting and Retching (three subscales: nausea, vomiting and retching, eight items, measures levels and distress caused by these; possible score range is eight to 40 representing no symptoms to maximal symptoms; the cut-off point for severe symptoms is 33. Originally created by Rhodes (Rhodes 1984) to measure the nausea and vomiting symptoms associated with chemotherapy, this index has been validated in studies of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (O’Brien 1996; Zhou 2001).

McGill Nausea Questionnaire: measures nausea only. This questionnaire includes a qualitative measure (sets of verbal, affective and other descriptors of nausea); a nausea rating index (nine sets of words ranked in order of increasing severity); an overall nausea index; and a visual analogue scale (no nausea to extreme nausea, 10 cm scale). Developed by Melzack for cancer chemotherapy and validated for use in studies of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (Lacroix 2000; Melzack 1985).

Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy Instrument: includes three questions, one each about nausea, vomiting and retching in the past week; possible range is zero to15; the cut-off point for severe symptoms is 8. Reliability and validity have been adequately described (Swallow 2002; Swallow 2005).

Visual analogue scales (graded 0 to 10) to record severity of nausea (Can Gurkan 2008; Pongrojpaw 2007; Vutyavanich 1995).

The primary outcome of reduction in symptoms, encompasses non-worsening of symptoms (including up to those of hyperemesis gravidarum).

Adverse maternal and fetal/neonatal outcomes

Adverse fetal/neonatal outcomes

Fetal or neonatal death. This includes spontaneous abortion, stillbirth (death of a fetus of at least 500 g weight or before 20 weeks’ gestation); neonatal death (death of a baby born alive, within 28 days of birth).

Congenital abnormalities (an abnormality of prenatal origin, including structural, genetic and/or chromosomal abnormalities and biochemical defects, but not including minor malformations that do not require medical treatment) (South Australian Health Commission 1999; Zhou 1999).

Low birthweight (less than 2.5 kg).

Early preterm birth (before 34 weeks’ gestation).

Adverse maternal outcomes

Pregnancy complications (antepartum haemorrhage, hypertension, pre-eclampsia (hypertension ≥ 140/90 mm Hg (millimetres of mercury), proteinuria ≥ 0.3 g/L from the 20th week of pregnancy).

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life

Quality of life outcomes encompass emotional, psychological, physical well-being; women’s assessment of the pregnancy experience; women’s ability to cope with the pregnancy. Measured using the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) and other generic Quality of Life (QoL) and other well-being (mental health) and coping measures (Attard 2002; Chou 2003; Lacasse 2008; Swallow 2004; Swallow 2005) and a validated pregnancy-specific Quality of Life instrument (Magee 2002b).

Economic costs

Direct financial costs to women (purchase of treatments).

Productivity costs (time off work).

Healthcare system costs (provision of services, consultation time, staff time) (Attard 2002; Koren 2005; Piwko 2007).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co-ordinator (28 May 2010).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co-ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co-ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Because of the non-pharmaceutical interventions which are recommended for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy, we also liaised with the Cochrane Complementary Medicine Field to identify any other trials.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third review author.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third review author. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2008) and checked them for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2009). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used to generate the allocation sequence in order to assess whether the process was truly random. We assessed the methods as:

adequate (e.g. random-number table; computer random number generator);

inadequate (odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence and determined whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

inadequate (open random allocation; unsealed or non-opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear.

(3) Blinding (checking for possible performance bias)

We have described for each included study all the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We have also provided information relating to whether the intended blinding was effective if this was available. We have noted where there had been partial blinding (e.g. where it was not feasible to blind participants, but where outcome assessment was carried out without knowledge of group assignment).

We assessed the methods as:

adequate, inadequate or unclear for participants;

adequate, inadequate or unclear for personnel;

adequate inadequate or unclear for outcome assessors.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We have described for each included study the completeness of outcome data for each main outcome, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We have stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition/exclusion where reported, and any re-inclusions in analyses which we undertook.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (e.g. where there was little or no missing data and where reasons for missing data were balanced across groups);

inadequate (e.g. where missing data were likely to be related to outcomes or not balanced across groups or where high levels of missing data were likely to introduce serious bias or make the interpretation of results difficult);

unclear (e.g. where there was insufficient reporting of attrition or exclusions to permit a judgement to be made).

(5) Selective reporting bias

We have described for each included study how the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias was examined by us and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (where it was clear that all of the study’s prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review were reported);

inadequate (where not all the study’s prespecified outcomes were reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used; study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear.

(6) Other sources of bias

We have described for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias. Potential examples would include where there was a risk of bias related to the specific study design, where a trial stopped early due to some data-dependent process, or where there was extreme baseline imbalance.

We assessed whether each study was free of other issues that could put it at risk of bias and assessed each as:

adequate;

inadequate;

unclear.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We have made explicit judgements about risk of bias for important outcomes both within and across studies. With reference to (1) to (6) above we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it was likely to impact on the findings. We have explored the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses, see Sensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we have presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we have used the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We have used the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

We have not included any crossover trials. We did not identify any cluster-randomised trials on this topic. If we had identified such trials, and they were otherwise eligible for inclusion, we would have included and analysed them with individually randomised trials using the methods set out in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2009).

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we have noted levels of attrition. We have explored the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

We have analysed data on all participants with available data in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. If in the original reports participants were not analysed in the group to which they were randomised, and there is sufficient information in the trial report, we have attempted to restore them to the correct group.

For all outcomes we have carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention-to-treat basis, i.e. we have attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial is the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We visually examined the forest plots for each analysis to look for obvious heterogeneity and used the I2 and T2 statistics to quantify heterogeneity among the trials. If we identified moderate or substantial heterogeneity (I2 greater than 50% and T2 greater than zero) we used a random-effects model in meta-analyses and have indicated the values of I2 and T2 and the P value for the Chi2 test for heterogeneity. For outcomes where there are high levels of heterogeneity we would advise caution in the interpretation of results.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where we suspected reporting bias (see ‘Selective reporting bias’ above), we attempted to contact study authors asking them to provide missing outcome data. Where this was not possible, and we thought that the missing data might introduce serious bias, we explored the impact of including such studies in the overall assessment of results by sensitivity analysis.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2008). We used fixed-effect meta-analysis for combining data where trials examined the same intervention, and we judged the trials’ populations and methods were sufficiently similar. Where we suspected clinical or methodological heterogeneity among studies sufficient to suggest that treatment effects might differ between trials, we used random-effects meta-analysis.

If we identified substantial heterogeneity in a fixed-effect meta-analysis, we repeated the analysis using a random-effects method.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned separate subgroup analyses by type of intervention, where comparability of trials and data allowed.

We planned to use the following primary outcomes in subgroup analysis.

Symptomatic relief (reduction or cessation of nausea, vomiting and/or retching);

adverse fetal and neonatal outcomes;

adverse maternal outcomes.

For fixed- and random-effects meta-analyses we planned to assess differences between subgroups by inspection of the subgroups’ confidence intervals; non-overlapping confidence intervals indicating a statistically significant difference in treatment effect between the subgroups. In this version of the review data were not available to carry out planned subgroup analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses where appropriate, for example where there was risk of bias associated with the quality of some of the included trials, or to explore the effects of fixed-effect or random-effects analyses for outcomes with statistical heterogeneity. However, as studies examined a variety of interventions we were able to pool only very limited data from a small number of studies. In updates of the review, if more data become available we will carry out planned sensitivity analyses.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

The search strategy identified 66 reports representing 55 studies (some of the studies resulted in more than one publication). Of these 55 studies, 27 met the inclusion criteria for the review, we excluded 22, four are awaiting further assessment, and two studies have not been completed yet.

Included studies

The included studies examined a range of interventions. Acupressure is a noninvasive variation of acupuncture which involves the application of constant pressure to specific points or areas. P6 (or Neigun point) acupressure is proposed to treat symptoms of nausea and vomiting (O’Brien 1996). The P6 point is located on the medial aspect of the forearm, at a specific point near the wrist. The effectiveness of acupressure to the P6 acupressure point was examined in five studies; in four of these the use of acupressure wrist bands was compared with placebo (Belluomini 1994; Norheim 2001; O’Brien 1996; Werntoft 2001), and in one with vitamin B6 (Jamigorn 2007) (in this study women in both groups also received a placebo intervention). One study examined the use of acustimulation to the P6 acupressure point (Rosen 2003). Another study compared auricular (on the ear) acupressure to placebo (Puangsricharern 2008). Two trials compared acupuncture with sham acupuncture (Knight 2001; Smith 2002); in one of these (Smith 2002) separate groups received traditional and P6 acupuncture.

The use of ginger (prepared as syrup or capsules) to relieve nausea was examined in nine studies; in four of these ginger was compared with a placebo preparation (Keating 2002; Ozgoli 2009; Vutyavanich 2001; Willetts 2003), in one with an anti-emetic (dimenhydrinate) (Pongrojpaw 2007), and in four studies the comparison group received vitamin B6 (Chittumma 2007; Ensiyeh 2009; Smith 2004; Sripramote 2003).

In two studies the intervention group received vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), which was compared with placebo preparations (Sahakian 1991; Vutyavanich 1995).

One study examined the use of moxibustion compared with traditional Chinese herbs (Fan 1995).

Six studies examined the use of antiemetic drugs: five compared placebo tablets with active treatment (fluphenazine (Price 1964), hydroxyzine hydrochloride (Erez 1971), Bendectin (Bentyl, Decapryn and pyridoxine) (Geiger 1959) or Debendox (a mixture of dicyclomine, doxylamine and pyridoxine) (McGuiness 1971), or thiethylperazine (Newlinds 1964)); one study (Bsat 2003) looked at the effectiveness of three different anti-emetics (metoclopramide with vitamin B6, prochlorperazine and promethazine).

All of the studies recruited women with symptoms of nausea (with or without vomiting) although we specifically excluded studies focusing on women with hyperemesis gravidarum. The severity of symptoms was not always made clear, and it is possible that some of the included studies may have recruited some women with more severe symptoms. One study included separate data for those women with the most severe nausea and vomiting (Rosen 2003), though not in a form that allowed us to analyse these separately as part of subgroup analysis.

The stage of pregnancy at which women were recruited to studies varied, although predominantly women were recruited during the first trimester (less than 12 weeks’ gestation). In one study (Fan 1995) women with gestational ages of more than eight weeks were included, but the upper limit was not specified; one study recruited women up to 20 weeks (McGuiness 1971), one up to 24 weeks (O’Brien 1996) and one up to 36 weeks (Price 1964). Although most of the women in these trials were in the first trimester and therefore, we did not wish to exclude the studies; separate figures were not provided on those women with nausea later in pregnancy, and so we were not able to exclude these women from the analyses. All of the studies collected outcome data on persistence of nausea symptoms or relief from nausea. Nevertheless, pooling data from studies was complicated by the variability in the way outcome data were collected and reported. The Rhodes Index of Nausea, Vomiting and Retching was used in nine studies (Belluomini 1994; Chittumma 2007; Jamigorn 2007; O’Brien 1996; Puangsricharern 2008; Rosen 2003; Smith 2002; Smith 2004; Willetts 2003). Not all studies collected or reported data on all dimensions (duration, frequency, distress) of the three subscales (nausea, vomiting, retching) included in the index. Eight studies collected ordinal data (Bsat 2003; Erez 1971; Fan 1995; Geiger 1959; Knight 2001; McGuiness 1971; Newlinds 1964; Price 1964). In these studies women were asked, for example, to rate symptoms on a five-point Likert-type scale or to describe the relief from symptoms on a three-point scale; we have converted some of the data from studies using such scales into binary data for incorporating them into the review. In 11 studies a visual analogue scale (VAS) was used (Keating 2002; Knight 2001 (for overall effectiveness rating); Ensiyeh 2009; Norheim 2001; Ozgoli 2009; Pongrojpaw 2007; Sahakian 1991; Sripramote 2003; Vutyavanich 1995; Vutyavanich 2001; Werntoft 2001). The wording on each VAS differed slightly, though in most cases women were asked to rate their symptoms on a 10 cm (or 100 mm) line, with 0 representing no symptom(s) (for example, no nausea) and 10 representing the worst symptom(s) (for example, the worst possible nausea). No authors provided details of validity or reliability testing of the VAS used.

Several studies reported the number of vomiting episodes recorded by women each day (Bsat 2003; Ensiyeh 2009; Keating 2002; Ozgoli 2009; Pongrojpaw 2007; Sahakian 1991; Sripramote 2003; Vutyavanich 1995; Vutyavanich 2001; Werntoft 2001), in addition to those above that used the Rhodes Index, which also measures frequency of vomiting. One study measured the use of rescue medication (Jamigorn 2007), and two others the use of over-the-counter and prescribed medication (Puangsricharern 2008; Rosen 2003).

In this review we chose to describe outcomes relating to women’s experience of nausea and vomiting at approximately three days after the start of treatment, as many of the studies provided data at this time point. We judged that this was a clinically meaningful point as most medication and other interventions would be expected to have achieved some effect within this timeframe. Where this information was not available, we chose the closest time point to three days that was reported. In the Characteristics of included studies tables, we have set out the time points when outcome data on symptoms were collected and reported in relation to the commencement of treatment. This information is important, as for many women symptoms are likely to resolve over time with or without treatment, particularly as the pregnancy progresses beyond the first trimester. In studies where outcome data were collected weekly over three or four weeks (e.g. Smith 2002; Smith 2004) we considered that differences between groups would be more difficult to detect at later follow-up points, and for these studies we have used symptom data from the earlier assessments (e.g. after seven days) in the data and analyses tables.

As well as symptomatic relief, our primary outcomes also included maternal and fetal/neonatal adverse effects. Five studies reported adverse fetal outcomes (Ensiyeh 2009; Erez 1971; Smith 2002; Vutyavanich 2001; Willetts 2003). Adverse maternal outcomes (such as preterm labour or spontaneous abortion) were reported for five studies (Ensiyeh 2009; Smith 2002; Smith 2004; Vutyavanich 2001; Willetts 2003). Worsening of symptoms was reported in two studies (Bsat 2003; Rosen 2003). Three studies reported on maternal weight loss/gain, which we had not prespecified as a maternal outcome (Jamigorn 2007; Keating 2002; Rosen 2003); this could be viewed as being related to symptom control, but is presented with the secondary outcomes in the results section. In addition, seven studies described the side effects of treatment such as headache, heartburn or sleepiness (Chittumma 2007; Erez 1971; Knight 2001; McGuiness 1971; Pongrojpaw 2007; Sripramote 2003; Willetts 2003).

Our secondary outcomes included quality of life of women during pregnancy, and economic costs (directly to women, productivity costs, and costs to the healthcare system). Two studies (Smith 2002; Smith 2004) measured Quality of LIfe using the MOS 36 Short Form Health Survey (SF36). One study (Knight 2001) used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. No studies measured economic costs.

See the Characteristics of included studies tables for more information on participants, interventions and outcomes measured.

Studies awaiting further assessment and ongoing studies

Four studies are awaiting further assessment; in all four cases studies were reported in brief abstracts, and our initial attempts to contact authors, or to identify subsequent publications have not been successful (Adamczak 2007; Biswas 2006; Hsu 2003; Mamo 1995). If we identify further reports from these studies we will reassess eligibility.

Two studies are ongoing. One multicentre trial (Nguyen 2008) examining the use of Diclectin (Debendox) for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy is planned to end in late 2009. We hope to include results from this study, if available, in updates of this review. Another study (Wibowo 2009) is comparing the effectiveness of different doses of vitamin B6 (“high” and “low” doses, which are undefined in the trial record).

Excluded studies

After assessment of study eligibility we excluded 22 studies identified by the search strategy. The main reason we excluded studies was because they were not randomised trials, or they used a crossover design. Six studies used quasi-randomised designs, for example allocation according to day of the week, or alternate allocation (Baum 1963; Can Gurkan 2008; Diggory 1962; Dundee 1988; Fitzgerald 1955; Winters 1961); such studies are at high risk of bias, and were therefore not included in the review. In three studies it was not clear to us that there was any sort of random allocation to groups (Conklin 1958; Lask 1953; Steele 2001). Seven studies used a crossover design (Bayreuther 1994; Cartwright 1951; De Aloysio 1992; Evans 1993; Hyde 1989; King 1955; Wheatley 1977); such designs are not usually appropriate during pregnancy when symptoms may not be stable over time. We excluded three studies as they focused on women with hyperemesis gravidarum, a group that we had decided to exclude from the review (Heazell 2006; Higgins 2009; Kadan 2009). Two of these studies are ongoing (Higgins 2009; Kadan 2009). We excluded one study because it was reported in a trial registry, and we found no evidence that the study had taken place; we carried out a search of databases to look for any publications from the study without success (Luz 1987). One study did not focus on the relief of nausea, but rather on hypocorticalism in pregnancy (Ferruti 1982); and finally, one trial record describes a study which looked at pre-emptive treatment (before any symptoms appear) with a combination of pyridoxine hydrochloride and doxylamine succinate (Diclectin) in a subsequent pregnancy for women who had experienced severe symptoms of nausea/vomiting of pregnancy (or hyperemesis gravidarum) in a previous pregnancy (Koren 2006).

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

Sequence generation

In eight of the included studies the method used to generate the randomisation sequence was not described or was not clear (Erez 1971; Fan 1995; Geiger 1959; McGuiness 1971; Ozgoli 2009; Pongrojpaw 2007; Price 1964; Werntoft 2001). In the study by Belluomini 1994 the trial was described as having a balanced block design, but it was not clear how the sequence order was generated or what the block size was. All the remaining studies were assessed as having adequate methods to generate the randomisation sequence: four studies used external randomisation services (Jamigorn 2007; Smith 2002; Smith 2004; Willetts 2003), five studies used computer-generated sequences (Bsat 2003; Keating 2002; Knight 2001; O’Brien 1996; Rosen 2003) (although the small block size in the Knight 2001 study (four) may have meant the sequence could be anticipated); and the remaining seven studies reported the use of tables of random numbers (Chittumma 2007; Ensiyeh 2009; Puangsricharern 2008; Sahakian 1991; Sripramote 2003; Vutyavanich 1995; Vutyavanich 2001).

Allocation concealment

In 12 studies the methods used to conceal the study group allocation were not described or were not clear (Belluomini 1994; Bsat 2003; Ensiyeh 2009; Erez 1971; Fan 1995; Newlinds 1964; Norheim 2001; Ozgoli 2009; Pongrojpaw 2007; Puangsricharern 2008; Sahakian 1991; Werntoft 2001). In the remaining studies we judged that the methods were adequate; four studies used an external randomisation service (Jamigorn 2007; Smith 2002; Smith 2004; Willetts 2003); five used sealed opaque sequentially numbered envelopes (Chittumma 2007; Knight 2001; Rosen 2003; Sripramote 2003; Vutyavanich 2001); one (O’Brien 1996) used numbered sealed envelopes, without stating if they were opaque or not; and in five placebo controlled trials, coded drug boxes or containers were used (Geiger 1959; Keating 2002; McGuiness 1971; Price 1964; Vutyavanich 1995).

Blinding

Most of the studies included in the review were placebo controlled. In three studies the routes of treatment administration (oral, injection etc) were different and double/multiple placebo control was not attempted (Bsat 2003; Chittumma 2007; Fan 1995). In two studies, where there were more than two active intervention arms, the type of treatment was blinded but the control condition (no intervention) was not (O’Brien 1996; Werntoft 2001). In all studies, all symptomatic outcomes were self-assessed by women, whether recorded by women themselves or a researcher.

The success of blinding was not reported in most trials. Where the treatment involved acupressure, acustimulation, or acupuncture, blinding may not have been convincing to women or clinical staff. In one acupuncture trial (Knight 2001), the author reported that there was no attempt to blind clinical staff, but women were described as being blind to group allocation. In five studies (Chittumma 2007; Knight 2001; Norheim 2001; Smith 2002; Smith 2004), the authors examined whether blinding was actually effective. It was reported in these studies that blinding may not always have been effective. We will return to this issue in the discussion.

Incomplete outcome data

The amount of missing outcome data in most of these studies was generally low, with attrition levels below 10%; in these studies most women were available to follow up, although there were missing data for some outcomes. There were higher rates of attrition in the studies by Pongrojpaw 2007 (11%), Willetts 2003 (17.5%), Rosen 2003 (18.6%), Knight 2001 (20%) and Newlinds 1964 (20%). In four studies attrition was greater than 20% (Sahakian 1991 (20.2%, attrition per group not stated); Smith 2002 (24% by week four of a four-week study), Smith 2004 (29.3% by day 21) and Belluomini 1994 (33%). The reasons for attrition varied and eight studies stated that women were lost to follow up for reasons that may have related to study outcomes (e.g. because they developed more severe symptoms, did not comply with taking study medication, or had adverse events) which may have put these studies at particularly high risk of bias (Belluomini 1994; Bsat 2003; Jamigorn 2007; Keating 2002; Knight 2001; Newlinds 1964; O’Brien 1996; Rosen 2003). In one study (Erez 1971), there was no attrition at three weeks, but for the later follow-up data on pregnancy outcome, there was high attrition (24%), as these women had given birth elsewhere. The reasons for this were not given, so it is possible that women were referred for high-risk deliveries or other adverse events; again, there may be a high risk of bias in this study. In one study (McGuiness 1971), the number of women randomised was not clear, making it impossible for us to assess attrition. In another study (Werntoft 2001), the approximate number of questionnaires (n = 80) given out was stated, and the study stopped when 20 per group returned them, but it is not known how many per group had been given out, and therefore, attrition cannot be accurately measured. Intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was reported for two studies (Jamigorn 2007 (drop-outs counted as treatment failures); Knight 2001), and Vutyavanich 2001 included the three placebo drop-out participants in the results, assuming relief equal to best improvement in the placebo group.

Selective reporting

Although most of the studies provided some data on nausea, or relief from nausea, information on other outcomes was sparse. Not all subscales were reported for instruments such as the Rhodes Index (Belluomini 1994). Data from only selected time points were presented in some studies (Belluomini 1994; Keating 2002). In one study, results were presented using the number of assessments of outcomes (280 assessments for 35 participants in the control group and 256 assessments for 32 participants in treatment group), rather than the number of participants (Ozgoli 2009). Statements in the text about results were not always backed up with numerical results (e.g. Belluomini 1994 (re results from days eight to 10);Bsat 2003 (re drug use and compliance)).

As stated above (Included studies), few studies described side effects from treatment or adverse events for mothers or babies.

In six studies we had difficulty interpreting outcome data as they were presented only, or largely, in graphical form (Bsat 2003; Jamigorn 2007; Norheim 2001; O’Brien 1996; Rosen 2003; Willetts 2003).

Some studies (Pongrojpaw 2007; Sahakian 1991; Smith 2002) provided a large amount of outcome data, for example, mean scores on several dimensions of scales recorded over several days. Interpreting such data is not simple, and increases the risk of spurious statistically significant findings.

Other potential sources of bias

Three studies reported drug company involvement (provision of drugs and placebo, funding, or other sources of support) (Keating 2002; McGuiness 1971; Willetts 2003). One study stopped early; in this trial it was stated that approximately 80 women were randomised, but the study was ended when 20 women in each of three groups had returned their data collection forms (Werntoft 2001). In the Price 1964 trial, some baseline imbalance between study groups in terms of gestational age at recruitment was reported, and in the Puangsricharern 2008 study there were differences in baseline demographic characteristics, with the control group participants having higher education and income levels than the treatment group. In one study (Geiger 1959), two women were included in both the treatment and control groups, as they received medication on two separate occasions when they visited the clinic during the study period. In several studies (for example, Jamigorn 2007 and Rosen 2003), women were free to take other medication which may have had a bearing on outcomes; without information on what other medication women were using, it is difficult to interpret these data. In the Bsat 2003 study, women in one of the intervention groups received vitamin B6 as well as the main intervention (an anti-emetic). Therefore, it is possible that the vitamin supplement had some independent or interaction effect on outcomes.

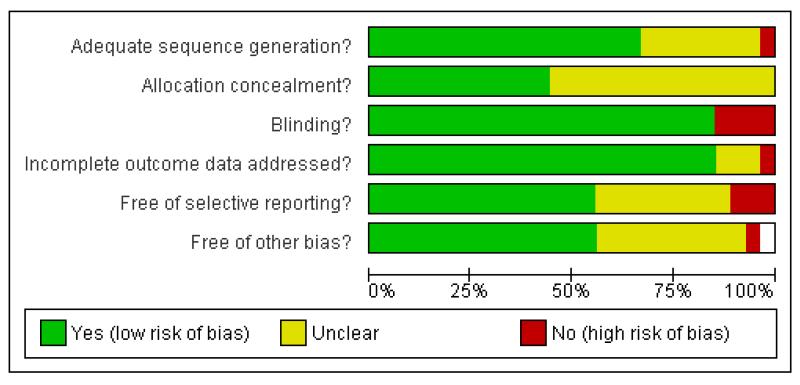

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the summary and graph of methodological quality, respectively. These highlight that, across studies, there is a lack of clarity on many ‘risk of bias’ criteria, particularly in relation to sequence generation and allocation concealment, selective reporting and other possible sources of bias.

Figure 1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Figure 2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Effects of interventions

Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy: 27 studies with 4041 women

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes for this review were as follows.

Symptomatic relief (specifically a reduction or cessation in nausea, retching and/or vomiting).

- Adverse maternal and fetal/neonatal outcomes.

- Adverse maternal outcomes included pregnancy complications (antepartum haemorrhage, hypertension, preeclampsia) .

- Adverse fetal/neonatal outcomes included fetal or neonatal death, congenital abnormalities, low birthweight or early preterm birth.

Symptomatic relief

P6 Acupressure versus placebo (four studies with 408 women)

Four studies compared P6 acupressure to placebo, and we have included data from three of these in the data tables. None of these studies showed evidence of a statistically significant effect for acupressure. Results from one study (Norheim 2001) favoured P6 acupressure for improving (i.e. reducing) the intensity of symptoms, but the difference between groups was not statistically significant (risk ratio (RR) 0.78, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.44 to 1.39). After three days of treatment there was no strong evidence that, compared with placebo, the treatment improved nausea in the Werntoft 2001 trial (mean difference (MD) 0.10, 95% CI −1.49 to 1.69). Using scores averaged over one to three days, results from the Belluomini 1994 study did not show that acupressure improved scores on the nausea and vomiting subscales or on the total Rhodes Index score (for nausea MD 0.39, 95% CI −0.80 to 1.58, for vomiting MD 0.26, 95% CI −1.06 to 1.58, for total Rhodes score MD 1.17, 95% CI −1.52 to 3.86).

One further study (O’Brien 1996) compared P6 acupressure and placebo, but data from this study were not in a form that allowed us to enter them into RevMan tables. The authors reported no statistically significant differences between treatment and placebo groups for symptom relief.

P6 Acupressure versus vitamin B6 (one study with 66 women)

Jamigorn 2007 compared P6 acupressure with vitamin B6 and results showed no statistically significant difference between the two interventions for improvement of nausea on day three (data obtained from authors) (MD 0.20, 95% CI −2.24 to 2.64). The authors also report on the use of rescue medication (which may be a proxy measure for lack of symptom relief); results favoured P6 acupressure (MD −2.2, 95% CI −3.98 to −0.42). Jamigorn 2007 also compared P6 acupressure and vitamin B6 in terms of satisfaction with the intervention (which could be considered as a proxy for its effectiveness); results suggest that women were more satisfied with acupressure but evidence of a difference between groups did not reach statistical significance (MD 0.40, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.84).

Auricular acupressure versus placebo (one study with 91 women)

One study compared auricular acupressure (administered by participants by pressing on magnetic balls taped to an acupressure point on the ear) with placebo (no treatment) (Puangsricharern 2008). The authors report that they were using mean total Rhodes Index score and total number of vomiting episodes from days four to six to measure treatment effect. They subsequently concluded that there were no significant differences between groups (though average Rhodes scores across these days were not directly reported). The treatment started on day three (for the acupressure group) and the results for the total Rhodes score at day six (three days after treatment started) appear to favour the treatment group, although scores were lower in this group at baseline so results are difficult to interpret (MD −3.60, 95% CI −6.62 to −0.58 Analysis 3.1). There were no differences between groups for the number of anti-emetic drugs used (MD - 0.10, 95% CI −0.37 to 0.17).

Acustimulation versus placebo (one study with 230 women)

Rosen 2003 compared low-level nerve stimulation therapy over the volar aspect of the wrist at the P6 point with placebo. In this study, nausea symptoms were recorded over three weeks, with weekly assessments of changes from baseline. The author reported the “time-averaged” change in the Rhodes Index total experience scale over the entire three-week study period, and suggested that there was more improvement over time in the active treatment group (change score 6.48 (95% CI 5.31 to 7.66) versus 4.65 (95% CI 3.67 to 5.63) in the placebo group (data not shown in analysis tables). In this study, both groups experienced improved scores over the evaluation period, and data (presented in graphical form in the study report) were not simple to interpret. Results for women in the Rosen 2003 study with mild to moderate symptoms were described in an abstract by De Veciana 2001, and in another brief abstract results were reported for those women with severe symptoms (Miller 2001). However, neither abstract provided usable data for subgroup analysis.

Acupuncture versus placebo (two studies with 648 women)

One trial compared traditional acupuncture, P6 acupuncture, sham acupuncture and no treatment (Smith 2002). The data tables show three comparisons: between both traditional and P6 acupuncture and sham acupuncture, and between traditional and P6 acupuncture. None of the results show significant differences (Analysis 5.1 to Analysis 7.3) for relief from nausea, dry retching and vomiting. Knight 2001 also compared acupuncture to placebo but the data were not in a form that allowed us to enter them in RevMan 2008 tables; the authors used median scores because of the skewness of the data. They report no statistically significant differences between the control and intervention groups for symptom relief.

Moxibustion versus Chinese drugs (one study with 302 women)

Fan 1995 reported that in a study comparing moxibustion with Chinese drugs, symptoms for all women in both groups either “improved” or were “cured”.

Ginger versus placebo (four studies with 283 women)

Ginger was compared with placebo in four studies (Keating 2002; Ozgoli 2009; Vutyavanich 2001; Willetts 2003), although one study did not provide data on symptomatic relief in a way which we could use (Willetts 2003). In a small study (n = 26) (Keating 2002), results favoured ginger over placebo for improving nausea by day nine (RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.82). Results also favoured ginger for stopping vomiting at day six (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.98). In the study by Vutyavanich 2001 (n = 70), results suggested that improvement in nausea symptoms was greater in the placebo group over four days of treatment (MD 1.20, 95% CI 0.22 to 2.18), but when ITT analysis was carried out (to include three missing patients in the placebo group counted as treatment failures), the evidence of a difference between groups was no longer statistically significant (MD 0.60 95% CI −0.51 to 1.71).

Ozgoli 2009 also compared ginger with placebo and presented the results on nausea intensity using the total number of nausea-intensity assessments per group (assessments were carried out twice daily over four days for each participant, resulting in a total of 280 assessments for treatment group and 256 assessments for control group). Apart from those results which are not easily interpreted, and have not been included in our analysis, improvements in nausea intensity are reported in percentages per group (from which numbers have been calculated and analysed in this review). Data on overall improvements appear to have been gathered during interview (by an unblinded researcher) on day five, rather than by comparing scores over time, but this is unclear. These results show a statistical difference between groups, favouring the treatment group (RR 1.48, 95% CI 1.07 to 2.04) on “nausea intensity improvement”. The authors also report a reduction in the incidence of vomiting following treatment of 50% in the intervention group compared with 9% in the control group, although the original data on post-treatment vomiting are not reported, and are not included in our analysis tables.

Ginger versus vitamin B6 (four studies with 624 women)

Four trials compared ginger and vitamin B6 (Chittumma 2007; Ensiyeh 2009; Smith 2004; Sripramote 2003).

In the two trials comparing ginger to vitamin B6 that had comparable outcomes reported (Chittumma 2007; Sripramote 2003), no statistically significant difference was found between groups (SMD −0.00, 95% CI −0.25 to 0.25, I2 = 0%) for symptom scores on day three. Results from the Chittumma 2007 study favoured ginger compared with vitamin B6 using the Rhodes Index to measure symptom relief, while in the Sripramote 2003 trial results favoured vitamin B6, using a 10 cm VAS to measure level of nausea; but neither of these results was statistically significant. Post-treatment number of vomiting episodes on day three was similar in the two intervention groups in the Sripramote 2003 trial (MD 0.00, 95% CI −0.60 to 0.60). Ensiyeh 2009 and Smith 2004 present results on improvement in symptoms and pooled results show no statistically significant difference between groups for the number of women reporting no relief (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.52 (random-effects)) although there was moderate heterogeneity for this outcome and results should be interpreted with caution (heterogeneity: T2 = 0.11, I2 = 52%. P = 0.15).

Ginger versus Dimenhydrinate (one study with 170 women)

One study (Pongrojpaw 2007) compared ginger and dimenhydrinate, but the results for symptomatic relief were not easily interpreted and therefore, data have not been added to data tables in RevMan 2008.

Vitamin B6 versus placebo (two studies with 416 women)

In two studies comparing vitamin B6 with placebo (Sahakian 1991; Vutyavanich 1995), results favoured vitamin B6 for reduction in nausea after three days (MD 0.92, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.44). Comparing the number of patients vomiting post-treatment, there was no strong evidence that vitamin B6 reduced vomiting (average RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.66). As there was high heterogeneity for this outcome we used a random-effects model and results should be interpreted with caution (heterogeneity: I2 = 77%, T2 = 0.25, P = 0.04).

Anti-emetic medication versus placebo (six studies with 803 women)

There were six studies of anti-emetic medications. A range of anti-emetics (Hydroxyzine, Debendox (Bendectin) Thiethylperazine and Fluphenazine-Pyridoxine) were compared with placebos, and in one study, three anti-emetic medications were compared. One study (Erez 1971) compared Hydroxyzine to placebo, with the results favouring Hydroxyzine for relief of nausea (RR 0.23 95% CI 0.15 to 0.36).

Bsat 2003 compared three drug regimens: Pyridoxine-metoclopromide, Prochlorperazine and Promethazine. Results were reported in graphs and we have not entered estimated figures into data tables. Approximately 65%, 38% and 40% of women in each group, respectively, responded that they felt better on the third day of treatment. The authors conclude that their results favour Pyridoxine-metoclopromide over the other two regimens.

Two studies (Geiger 1959 and McGuiness 1971) compared Debendox (Bendectin) with placebo, and results for nausea relief favoured the intervention group. However there was high heterogeneity when results from these two studies were combined, and the time point at which outcome data were collected was not clear in the McGuiness 1971 study, and so in the analyses we have provided subtotals only. In the McGuiness 1971 study, while fewer women in the Debendox group had no relief in symptoms, the difference between groups was not statistically significant (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.17). In the Geiger 1959 study, only three of 52 women receiving Debendox reported no improvement in symptoms compared with 20/57 for controls.

Thiethylperazine was compared with placebo in one study and women in the placebo group were less likely to experience symptom relief (RR 0.49 95% CI 0.31 to 0.78) (Newlinds 1964). Finally, fluphenazine-pyridoxine seemed to improve symptoms compared with placebo in one trial, but results did not reach statistical significance (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.01) (Price 1964); this is an antipsychotic drug (from the piperazine class of phenothiazines).

Adverse maternal and fetal/neonatal outcomes

Adverse maternal and fetal outcomes were reported for some studies across several comparisons.

Acupressure versus vitamin B6

Weight gain was reported by Jamigorn 2007 and results favoured the acupressure group (MD 0.70, 95% CI 0.24 to 1.16), with higher weight gain in this group.

Acupressure versus placebo

Norheim 2001 reported that 63% of participants in the acupressure group and 90% in the placebo group reported problems (including pain, numbness, soreness and hand-swelling) using the wristband. Three women (two in the treatment group, one in the placebo group) said they felt more sick during the study period.

Acustimulation versus placebo

Rosen 2003 reported on weight gain, dehydration and ketonuria. There was significantly more weight gain and less dehydration in the treatment group (MD 1.70, 95% CI 0.23 to 3.17; RR 0.24, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.83 respectively) but there was no significant difference for ketonuria at the end of the trial period (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.15 to 1.55). The authors report that there was no significant difference between groups on entry to the trial for ketonuria, though those most likely to withdraw from the study had ketonuria at entry (but at non-significant level).

GInger versus placebo

Vutyavanich 2001 reported on the rates of spontaneous abortion, with no significant difference between groups (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.04 to 3.33). Similarly, for delivery by caesarean section, there was no difference between groups (RR 1.64, 95% CI 0.51 to 5.29). The authors reported that there were no congenital abnormalities in either group. As with the other studies reporting such fetal outcomes, this study did not have sufficient power to show differences between groups; we will return to this in the discussion.

Willetts 2003 compared fetal adverse outcomes (such as stillbirth, neonatal death, preterm delivery, congenital abnormalities) with expected numbers based on data at one hospital in Sydney. The results were not clearly presented by randomisation group, but were shown for the overall number who completed the main study, with descriptive text about the number in the ginger group. The authors concluded that those exposed to ginger did not appear to be at greater risk of fetal abnormalities.

Also in a study of ginger versus placebo, Keating 2002 reported weight change measured at the four week follow-up visit, but data were not presented in a usable form; the authors commented that most women in both groups maintained or gained weight.

Ginger versus vitamin B6

Smith 2004 reported on outcomes including spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, heartburn, congenital abnormality, antepartum haemorrhage/abruption or placenta praevia, pregnancy-induced hypertension, pre-eclampsia and preterm birth. There were no neonatal deaths in either group and no significant differences between the groups (Analysis 9.4 to Analysis 9.10). Similarly in Ensiyeh 2009, no significant differences were found in the maternal and fetal outcomes reported (spontaneous abortions, caesarean delivery, congenital anomaly of the baby (Analysis 9.4, Analysis 9.6, Analysis 9.15). The authors report that “all were discharged in good condition”, though elsewhere they say that data collection and follow up took 12 weeks; women were recruited to the trial at 17 weeks’ gestation or less, implying a longer follow-up time. Chittumma 2007 reported on arrhythmia and headache, with no evidence of a difference in effect between groups (Analysis 9.12; Analysis 9.11). Two studies (Chittumma 2007; Sripramote 2003) report results for heartburn, with no significant effect (RR 2.35, 95% CI 0.93 to 5.93, heterogeneity: I2 = 3%, P = 0.31). Chittumma 2007 reported on drowsiness, with neither ginger nor vitamin B6 favoured (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.56). Sripramote 2003 reported on sedation, with no strong evidence for either intervention (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.39).

Ginger versus dimenhydrinate

Pongrojpaw 2007 reported on the side effects of drowsiness and heartburn. More people in the dimenhydrinate group experienced drowsiness, while more in the ginger group experienced heartburn, but evidence of differences between groups was not statistically significant (drowsiness: RR 0.08, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.18; heartburn: RR 1.44, 95% CI 0.65 to 3.20).

Antiemetic drugs

In the trials of anti-emetic drugs, fetal outcome was recorded only by Erez 1971. In that study, of the 79 cases available for follow up in the hydroxyzine group, there were four spontaneous abortions (three in the first trimester and one in the second trimester) and one perinatal death. In the 36 cases available for follow up from the placebo group, there were two first trimester spontaneous abortions (spontaneous abortions: RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.17 to 4.75; perinatal mortality: RR 1.39, 95% CI 0.06 to 33.26). In the text, the authors report that slight drowsiness was reported by 7% (n = 7) of the treatment group, but no other adverse effects were reported, and there were no hospitalisations in either group.

Bsat 2003 reported a non-significant difference in hospitalisation across the three groups receiving pyridoxine-metoclopramide, prochlorperazine and promethazine. They comment that subsequent pregnancy courses were similar and only one neonatal anomaly was seen (a cardiac defect in the prochlorperazine group). McGuiness 1971 stated that side effects were reported by 12 patients in the Debendox group (including drowsiness for three patients, feeling weak for two, tiredness for two) compared to six adverse effects reported in the placebo group (including tiredness, sleepiness, depression and constipation). Newlinds 1964 reported that side effects occurred in 12 of the 93 patients who received thiethylperazine and 10 of the 87 in the placebo group. These adverse effects included drowsiness (four treatment, three placebo), aggravation of nausea (two treatment, three placebo), “cerebral stimulation”, described as mild in the text, and included restlessness (two in treatment group, none in placebo). Price 1964 reported that there were no side effects in the fluphenazine-pyridoxine group and one patient in the placebo group reported drowsiness. Geiger 1959 reported that one patient in the Bendectin group reported listlessness; no other adverse effects were reported.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes for this review were:

quality of life (emotional, psychological and physical well-being, women’s assessment of the pregnancy experience, women’s coping with the pregnancy);

economic costs (direct financial costs to women, productivity costs and/or health system costs).

Only three studies reported quality of life (and related) results (Knight 2001; Smith 2002; Smith 2004).

Knight 2001 used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and reported median scores for the intervention and control groups, but the data were not in a form that allowed us to enter them in RevMan 2008 tables. The authors report that for both anxiety and depression scores, there was no evidence for a group effect or a group-time effect, but there was for a time effect (in favour of acupuncture). However, both scores dropped over the course of the study for both groups. The median rating of global effectiveness was the same for both groups.

Smith 2002 and Smith 2004 used the MOS 36 Short Form Health Survey. Smith 2002 reported the change in mean scores on the SF36 Form (Quality of Life) for the four groups receiving traditional acupuncture, P6 acupuncture, sham acupuncture and no treatment, respectively. They report eight sets of results for three time points and highlight in the text that there was a group effect on the social function and mental health SF36 domains, favouring traditional acupuncture in both cases. Smith 2004 also reported changes in mean scores across eight domains of the SF-36, with a significant difference, favouring ginger, found only in two domains: social function and physical role function.

No study reported economic data of any sort.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

Nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy are common. Symptoms are generally self-limiting, are not usually life threatening and, provided women do not have very severe vomiting, do not often lead to serious complications. Nevertheless, early pregnancy nausea and vomiting may be extremely distressing to women, and may disrupt their physical and social functioning. In this context, and in view of concerns about the possible teratogenic effects of pharmacological agents, non-pharmacological approaches to symptom control have become increasingly popular and have been recommended in clinical practice guidelines (NICE 2008).

In this review we found little strong or consistent evidence that non-pharmacological therapies are effective in reducing symptoms. Evidence regarding the effectiveness of P6 acupressure (including acustimulation at this point) was limited. There was some evidence of the effectiveness of auricular acupressure, though further larger studies are required to confirm this. Acupuncture (P6 or traditional) showed no significant benefit to women with nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. The use of preparations containing ginger may be helpful to women, but in this review the evidence of effectiveness was limited, and not consistent.

We also found only limited evidence from trials to support the use of pharmacological agents including vitamin B6, antihistamines, and other anti-emetic drugs to relieve mild or moderate nausea and vomiting (a related Cochrane review is examining their use in women with more severe symptoms). There were no studies of dietary or other lifestyle interventions identified.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We attempted to be as inclusive as possible in the search strategy and have included studies reported in languages other than English. Nevertheless, the literature included in the review was predominantly reported in European and North American journals and this may have introduced some bias and limited the applicability of results.

Interpreting the findings of the studies included in the review was not simple. Some of the studies were more than 50 years old and during the time period covered by this research, the attitudes of women and clinical staff towards symptoms and towards symptom relief may have changed. Most of the studies examining nonpharmacological approaches have been published more recently, yet there is very little conclusive evidence on the efficacy of complementary or alternative therapies.

The main focus of the review was on the effectiveness of interventions to relieve symptoms. However, our prespecified outcomes also included the impact of interventions on the well-being of mothers and babies. Although there may be a perception that complementary and alternative approaches are not ‘invasive’, their safety has not been adequately evaluated. Few studies reported pregnancy outcomes, adverse effects from treatments, or adverse events. It may not be safe to assume that because negative outcomes were not reported that they did not occur. In those studies (mainly those focusing on pharmacological interventions) that did report data on side effects and adverse events, none had the statistical power to provide convincing evidence regarding relatively rare adverse outcomes.

The studies reviewed here contained very little information on the psychological, social or economic impact of nausea on pregnant women. The scales used tended to focus on the experience of symptoms; but very little data were presented on other aspects of quality of life such as the impact of nausea on family and social functioning, or on relationships. Many women experience symptoms whilst attempting to care for young children or whilst attending work; none of the studies reported on outcomes relating to the impact of interventions on the ability to perform work, on sickness absence from work, or on the economic impact of symptoms.

Some of the interventions examined in the review, such as ginger or acupressure wrist bands, may be transferable to clinical contexts other than those in which they were tested as they may be relatively low cost (although studies did not provide information on this) and acceptable to women and staff. Other interventions may require special equipment not generally available in antenatal care settings (e.g. acustimulation or acupuncture) and staff may need particular skills and training; even if these interventions had been proven effective, they may not be easily transferable between care settings.

Quality of the evidence

We were unable to pool findings from studies for most review outcomes due to heterogeneity in study participants (e.g. stage of pregnancy and severity of symptoms), interventions (and co-interventions), comparison groups, and outcomes measured or reported. For this reason, most of the results were derived from single studies with findings that have not been replicated elsewhere. Where results from more than one study were pooled, inconsistencies in findings between studies was reflected in high levels of statistical heterogeneity for some outcomes; we have indicated in the results section those outcomes affected by high heterogeneity and advise caution in interpreting those results.

The methodological quality of the included studies was mixed. Some studies had high rates of attrition, poor allocation concealment and other methodological problems which put them at high risk of bias. Lack of effective blinding may also have introduced bias; although many of the included studies were described as being double blind or keeping women blind to group allocation, we had concerns about the effectiveness of blinding. Sham acupressure, acupuncture or acustimulation may not be convincing to women. Some of the trials which investigated the effectiveness of blinding provided some evidence that women may have had some idea of group allocation (Chittumma 2007; Knight 2001; Norheim 2001; Smith 2002; Smith 2004). The lack of blinding or unconvincing blinding may be particularly relevant where the main outcome is women’s subjective, self-reported symptoms. We had intended to carry out sensitivity analysis whereby we would exclude from the analyses those studies at high risk of bias to see what impact this would have on findings; however, we did not do this because we were unable to pool data for most interventions and outcomes, and results were derived from single trials.

Lack of clear information on how studies were conducted and in reporting results means that some findings may be difficult to interpret. Few of the studies provided clear information on whether or not women were using other over-the-counter remedies or prescribed medications to control symptoms. This information would have been very helpful in understanding results. One study reported the use of “rescue” medication (Jamigorn 2007). In other studies the treatment effect may have been underestimated if women in control groups were more likely than those in intervention groups to use other treatments.

The effectiveness of vitamin B6 was difficult to interpret. In some studies, vitamin B6 was the active intervention, in others it was the control condition, and in at least one study it was given in addition to one of the interventions (Bsat 2003); in this study it was not clear whether the results obtained for the anti-emetic plus B6 group were attributable to the anti-emetic alone, vitamin B6 alone or both acting together.

The way in which outcomes were measured and reported in studies varied considerably. Some studies used the validated instruments described under Primary outcomes. Other studies used ordinal data such as three- or five-point scales. In these cases, in order to include data in the analysis tables, we converted the data into binary form by choosing cut-off points. We attempted to be consistent in choice of cut off, opting for no relief versus improvement in symptoms, but we acknowledge that the choice may have impacted the results. There was also variation in the way continuous data were collected, with some studies using visual analogue scales or validated scales. Eight studies in the review used the Rhodes Index. This was originally created to measure the nausea and vomiting symptoms of chemotherapy (Rhodes 1984), and has been validated for use in studying these symptoms in pregnancy (Zhou 2001). However, the use of Rhodes Index of Nausea, Vomiting and Retching, for example, was not consistent in studies; some trials used shortened forms or did not collect or report data on all subscales. Further, as we mentioned earlier, in some trials data were collected repeatedly and a great deal of (not always consistent) data were presented. In this review we have tried to present findings for a time point approximately three days after the start of treatment, but this was not always possible. The lack of consistency in the way outcome data were measured and reported should be kept in mind when interpreting results.

The use of pregnancy-specific nausea and vomiting measurement instruments in future studies may facilitate better outcome measurement. As described in Primary outcomes, the Pregnancy Unique Quantification of Emesis (and nausea) (PUQE) has been has been developed by clinician-researchers at the Canadian Motherisk Program. This is a three-item (plus a global question) instrument. The clinician-researchers had been using the Rhodes Index and stated that they found it to be detailed but cumbersome and time-consuming (Koren 2002b). They also noted the strong correlations between the severity of a physical symptom and the stress caused by that symptom. Also nausea was measured twice (duration and number of bouts (frequency) of nausea). They also felt that, based on their experience, frequency of nausea was more difficult for women to define. The PUQE has been validated against four independent criteria (Koren 2005) and with an established Quality of LIfe instrument (Lacasse 2008) and it has been used in studies that were not included in this review (for example Koren 2006). Other pregnancy-specific instruments have been developed (Magee 2002b; Swallow 2002) but these have not been used in published randomised controlled trials identified within this review).

Potential biases in the review process

We acknowledge that there was the potential for bias at all stages in the reviewing process. We attempted to minimise bias in a number of ways; for example, two review authors independently carried out data extraction and assessed risk of bias. However, we acknowledge that such assessments involve subjective judgments, and another review team may not have agreed with all of our decisions. A further possible source of bias (discussed above) was the choice of time points for symptom assessment and the cut off points chosen to convert ordinal into binary data for entry into RevMan 2008. Again, we attempted to minimise bias by discussing such issues and attempting to be consistent across studies and outcomes.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Current clinical practice guidelines suggest that acupressure and ginger may be useful in the relief of symptoms of nausea and vomiting (NICE 2008). Our results suggest that the evidence underpinning such recommendations is inconsistent and relatively weak.