Abstract

CHARGE syndrome is a congenital disorder caused by mutation of the chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 7 (CHD7) gene and is characterized by multiple anomalies including ocular coloboma, heart defects, choanal atresia, retarded growth and development, genital and/or urological abnormalities, ear anomalies, and hearing loss. In the present study, 76% of subjects had some type of endocrine disorder: short stature (72%), hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (60%), hypothyroidism (16%), and combined hypopituitarism (8%). A mutation in CHD7 was found in 80% of subjects. Here, we report the phenotypic spectrum of 25 Japanese patients with CHARGE syndrome, including their endocrinological features.

Keywords: CHARGE syndrome, CHD7, endocrinological features

Introduction

CHARGE syndrome is a disorder with multiple anomalies. The occurrence of the syndrome was estimated to be approximately 1:8,500 births by Issekutz et al. in 2005 (1). The syndrome was first reported in 1979 by Hall and Hinter, and Pagon et al. proposed its main features in 1981 (2). The syndrome was named for the acronym of coloboma of the eyes, heart defects, atresia choanae, retarded growth and development, genital and/or urological abnormalities, and ear anomalies and hearing loss. The criteria for CHARGE syndrome were defined by Blake et al. in 1998 (3) and updated by Verloes in 2005 (4). In 2004, chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 7 (CHD7), located on chromosome 8q12.1, was identified as the main gene responsible for the syndrome (5). Patients with CHARGE syndrome have not only various clinical features but also various anomalies, and Japanese patients with the syndrome have been reported (6,7,8). The present study delineated the phenotypic spectrum of 25 Japanese patients with CHARGE syndrome including their endocrinological features.

Subjects and Methods

The subjects were 25 Japanese patients (13 males and 12 females, aged from 1 to 25 yr) with CHARGE syndrome who were followed regularly at the authors’ institution over the past 20 yr. A clinical geneticist diagnosed them by referring to Blake’s and/or Verloes’ criteria.

CHD7 was analyzed in 21 subjects as described previously (6, 7). Briefly, all the coding exons 2–37 and their splice sites were PCR amplified from leukocyte genomic DNA of the patient, and the PCR products were screened for a mutation by denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) using an automated instrument (WAVE, Transgenomic, Omaha, NE, USA). When abnormal heteroduplex patterns were detected, the corresponding PCR products were subjected to direct sequencing on an ABI PRISM 3100 autosequencer (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA, USA).

Using the patients’ medical records, we studied their phenotypes with a focus on endocrine disorders.

Results

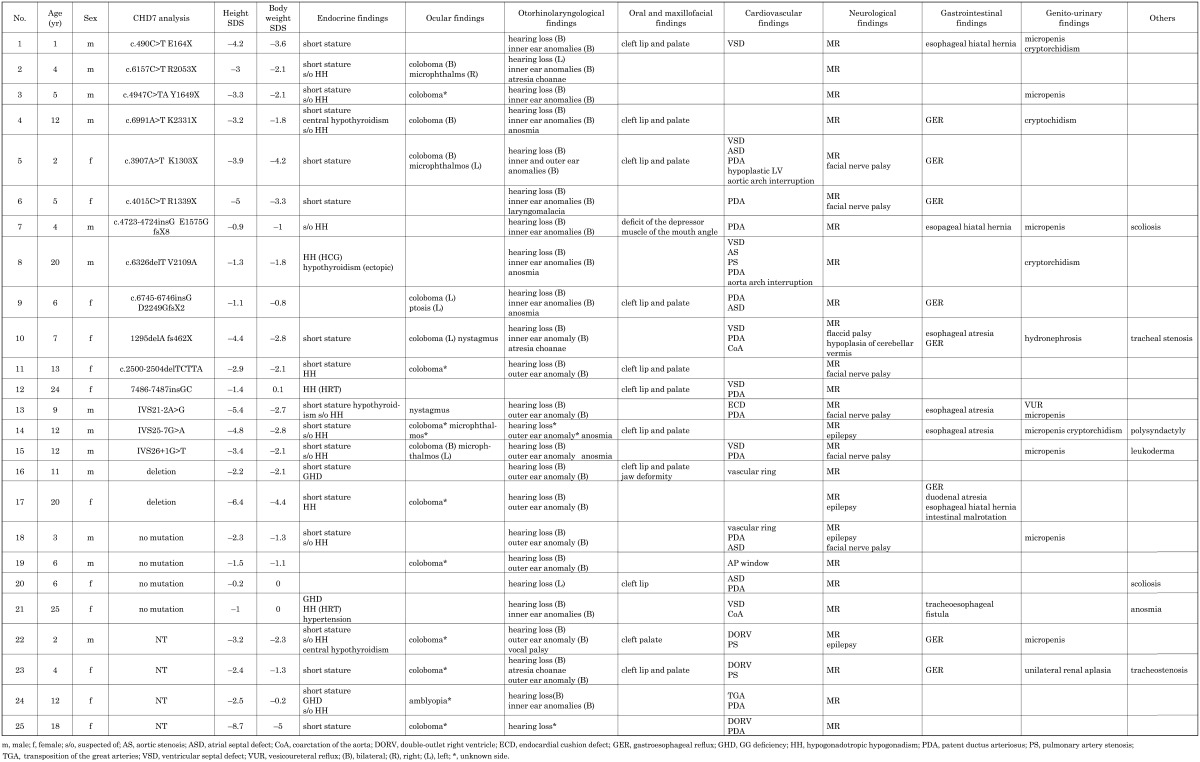

The characteristic clinical features of each patient are shown in Table 1. All patients had mental retardation and hearing loss. The patients also had congenital heart defects (76%), short stature (72%), genital disorders including micropenis and cryptorchidism (77% in males), ocular coloboma (56%), gastrointestinal disorders (52%), ear anomalies (44%), and cleft lip and/or palate (44%). Twenty-two patients (88%) had some type of endocrine disorder, including short stature.

Table 1. Characteristics of the 25 patients with CHARGE syndrome.

Clinical features

Endocrinological findings

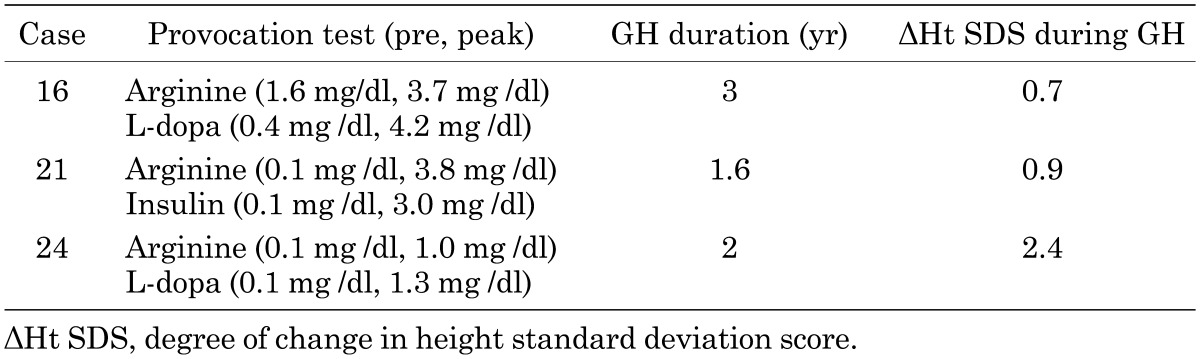

Short stature was the most frequent problem (72%), and the mean height was –3.04 standard deviation (SD) in 12 males (from –5.4 to –0.9 SD) and –3.64 SD in 10 females (from –6.4 to –0.2 SD), excluding 3 patients with growth hormone replacement therapy for GH deficiency (GHD) at the time of this study. In the 3 subjects (cases 16, 21 and 24) with GHD, the mean acquired degree of change in height (ΔHt SDS) was +1.33 SD during growth hormone therapy (0.175 mg/kg/wk), and the mean duration of growth hormone replacement therapy was 2.2 yr (Table 2). They had normal findings for the pituitary on head magnetic resonance imaging.

Table 2. Summary of patients with GHD.

Meanwhile, there were 15 patients (52%) with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (HH), including cases with suspected delayed puberty and 10 boys with genital hypoplasia. Three patients (12%) had received gonadal hormone therapy: hCG 1500 units once a week i.m. in case 8 and Kaufmann treatment in cases 12 and 21. Among the subjects with HH, 6 patients with relatively mild mental retardation (cases 4, 8, 9, 14, 15 and 21) were suspected of anosmia by self-evaluation for strong odors, such as spicy food. Four patients (16%) had hypothyroidism: cases 4 and 22 had central hypothyroidism with a low response in the thyrotropin-releasing hormone loading test, and cases 8 and 13 had primary hypothyroidism and received thyroxine replacement therapy. The growth rate improved in case 4, from –4.2 to –2.8 SD, for 4 yr before puberty after thyroxine replacement. Two cases (8%) with combined pituitary hormone deficiency with GHD and gonadotropin deficiency received growth hormone and gonadal hormone replacement therapy. One patient had hypertension (case 21). Electrolyte abnormalities were not observed in any of the patients.

Others

Ocular findings: Sixteen patients (64%) had ocular defects: coloboma with a various combination of iris, retina and disc defects in 14 patients, microphthalmus in 4 patients, nystagmus in 2 patients, and ptosis of the eyelid and amblyopia in 1 patient each. Although coloboma seems to be found in 75% of patients (7), representing one of the major features of CHARGE syndrome, its frequency was 56% in our subjects.

Otorhinolaryngological findings: All patients had hearing loss, and inner ear anomalies on temporal head computed tomography were found in 12 subjects. External ear anomalies were found in 13 subjects, with a suspicion of anosmia in 6 subjects, atresia choanae in 3 subjects, and laryngomalacia and vocal cord palsy in 1 subject each. All subjects with atresia choanae had a cleft lip and palate.

Oral and maxillofacial findings: Thirteen (52%) patients had oral and maxillofacial complications: cleft lip and/or palate in 11 patients, jaw deformity in 1 patient and deficit of the depressor muscle at the angle of the mouth in 1 patient.

Cardiovascular findings: Nineteen patients (76%) had cardiovascular anomalies: ventricular septal defect in 7 patients, double-outlet right ventricle in 3 patients, endocardial cushion defect in 1 patient, coarctation of the aorta in 2 patients, atrial septal defect in 6 patients, patent ductus arteriosus in 12 patients, pulmonary artery stenosis in 2 patiens, vascular ring in 2 patients, aortic arch interruption in 1 patient, and transposition of the great arteries in 1 patient.

Neurological findings: All patients had various degrees of mental retardation. Nevertheless, we should note the unreliability of the results for the development assessment test used because of the hearing loss and dystopia of the patients. We found VII cranial nerve palsy in 6 patients, epilepsy in 4 patients, hypoplasia of the cerebellar vermis in 2 patients, and flaccid palsy and hydrocephalus in 1 patient each.

Gastrointestinal findings: Gastrointestinal disorders were found in 13 patients (52%): gastroesophageal reflux in 8 patiens including 4 patients received fundoplication), esophageal closure in 4 patients, esophageal hiatal hernia in 3 patients, and duodenal closure, tracheoesophageal fistula and intestinal malrotation in 1 patient each.

Genital and urological findings: Genital and urological features were found in 12 patients (48%): genital hypoplasia including micropenis and cryptorchidism in 8 patients and unilateral renal aplasia, hydronephrosis and vesicoureteral reflux in 1 patient each.

In addition, there were 2 patients with tracheostenosis, 1 patient with congenital scoliosis, 1 patient with leukoderma and 1 patient with polysyndactyly.

Mutation analysis of CHD7

In the 21 patients analyzed, 17 patients (80%) had a mutation in CHD7: a nonsense mutation in 7 patients (41%), frameshift mutation in 5 patients (29%), splice site mutation in 3 patients (17%) and gene deletion in 2 patients (10%). No mutation in CHD7 was found in 4 patients (19%). No novel mutation was found in this study.

Discussion

The endocrinological findings in CHARGE syndrome have been reported in some studies (8,9,10,11). Although HH was commonly reported, the frequency of HH was less than that of the previous study for girls before puberty. Additionally, HH in association with anosmia is a symptom that overlaps with Kallmann syndrome, which classically consists of an impaired sense of smell and gonadotropin deficiency. Bergman et al. also suggested that anosmia seems to be a predictor for the occurrence of HH in CHARGE syndrome because genital hypoplasia is a predictor only in boys and there is no way to make a diagnosis until puberty in girls (12). In our study, 6 patients with HH including suspected cases had smell disorders based on their self-evaluations. However, the frequency was unclear because it is possible that the patients with severe mental retardation did not answer correctly.

As for the other symptoms, we observed GHD, hypothyroidism and combined hypopituitarism with GHD and HH. However, growth hormone secretion was not assessed in the majority of these patients unless they or their family desired for growth therapy, and we could not determine the precise frequency of GHD in our patients.

According to a previous report, there is no significant correlation between phenotype and genotype in CHARGE syndrome. However, Jogmans et al. reported that 85% of boys and 70% of girls with gonadotropin deficiency had a CHD7 mutation (13). In our subjects with a CHD7 mutation, 94.1% had some type of endocrinological problem, and 64.7% had HH. In subjects without CHD7 mutation, 75% had some endocrinological problems, and 50% had HH. In addition, 76.4% with a CHD7 mutation and CHD7 deletion and 62.8% without a CHD7 mutation had short statures. This suggests that the syndrome has a relatively higher frequency of endocrinological disorders with CHD7 mutation and deletion, but all patients must be assessed periodically for endocrinolgical status on routine follow-up.

Conclusions

We reported the phenotype of CHARGE syndrome, including endocrinological findings. Endocrine disorders were also one of the core symptoms in CHARGE syndrome, and it is thus necessary to assess the endocrine status of patients with this syndrome. CHD7 mutations were detected in 80% of the patients who underwent gene analysis.

The phenotypic spectrum of CHARGE syndrome is heterogeneous, and it is sometimes difficult to make a diagnosis because of unfulfilled criteria. It is helpful to make a diagnosis according to CHD7 mutation analysis. The authors believe that accumulation of data for delineation of the phenotypic spectrum of CHARGE syndrome will lead to better clinical management of patients.

References

- 1.Issekutz KA, Graham JM, Jr, Prasad C, Smith IM, Blake KD. An epidemiological analysis of CHARGE syndrome: preliminary results from a Canadian study. Am J Med Genet A 2005;133A:309–17. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pagon RA, Graham JM, Jr, Zonana J, Yong SL. Coloboma, congenital heart disease, and choanal atresia with multiple anomalies: CHARGE association. J Pediatr 1981;99:223–7. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(81)80454-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blake KD, Davenport SLH, Hall BD, Hefner MA, Pagon RA, Williams MS, et al. CHARGE association: an update and review for the primary pediatrician. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1998;37:159–73. doi: 10.1177/000992289803700302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verloes A. Updated diagnostic criteria for CHARGE syndrome: a proposal. Am J Med Genet A 2005;133A:306–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vissers LE, van Ravenswaaij CM, Admiraal R, Hurst JA, de Vries BB, Janssen IM, et al. Mutations in a new member of the chromodomain gene family cause CHARGE syndrome. Nat Genet 2004;36:955–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aramaki M, Udaka T, Kosaki R, Makita Y, Okamoto N, Yoshihashi H, et al. Phenotypic spectrum of CHARGE syndrome with CHD7 mutations. J Pediatr 2006;148:410–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogata T, Fujiwara I, Ogawa E, Sato N, Udaka T, Kosaki K. Kallmann syndrome phenotype in a female patient with CHARGE syndrome and CHD7 mutation. Endocr J 2006;53:741–3. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.K06-099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zenter GE, Layman WS, Scacheri PC. Molecular and phenotypic aspects of CHD7 mutations in CHARGE syndrome. Am J Med Genet PART A 152A:674–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Asakura Y, Toyota Y, Muroya K, Kurosawa K, Fujita K, Aida N, et al. Endocrine and radiological studies in patients with molecularly confirmed CHARGE syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:920–4. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishikawa A, Enomoto K, Furuya N, Muroya K, Asakura Y, Adachi M, et al. Clinical features in 26 patients with CHARGE syndrome. The Journal of the Japan Pediatric Society 2012;116:1357–64 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wheeler PG, Quigley CA, Sadeghi-Nejad A, Weaver DD. Hypogonadism and CHARGE association. Am J Med Genet 2000;94:228–31. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergman JE, Bocca G, Hoefsloot LH, Meiners LC, van Ravenswaaij-Arts CM. Anosmia predicts hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in CHARGE syndrome. J Pediatr 2011;158:474–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jongmans MC, Admiraal RJ, van der Donk KP, Vissers LE, Baas AF, Kapusta L, et al. CHARGE syndrome: the phenotypic spectrum of mutations in the CHD7 gene. J Med Genet 2006;43:306–14. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.036061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]