Abstract

Objective

Non-adherence to medication is common among coronary heart disease patients. Non-adherence to medication may be either intentional or unintentional. In this analysis we provide estimates of intentional and unintentional non-adherence in the year following an acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

Method

In this descriptive prospective observational study of patients with confirmed ACS medication adherence measures were derived from responses to the Medication Adherence Report Scale at approximately 2 weeks (n = 223), 6 months (n = 139) and 12 months (n = 136) following discharge from acute treatment for ACS.

Results

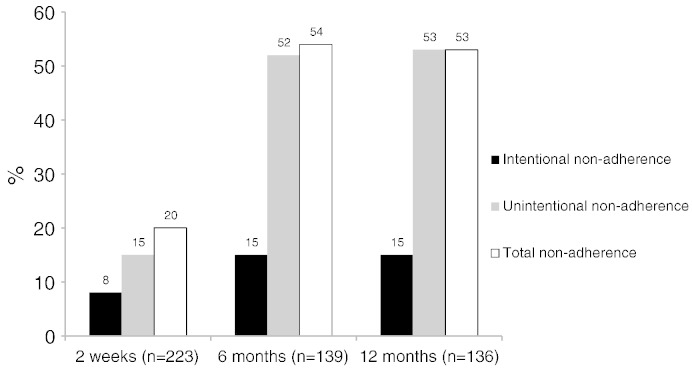

Total medication non-adherence was 20%, 54% and 53% at each of these time points respectively. The corresponding figures for intentional non-adherence were 8%, 15% and 15% and 15%, 52% and 53% for unintentional non-adherence. There were significant increases in the levels of medication non-adherence between the immediate discharge period (2 weeks) and 6 months that appeared to stabilize between 6 and 12 months after acute treatment for ACS.

Conclusion

Unintentional non-adherence to medications may be the primary form of non-adherence in the year following ACS. Interventions delivered early in the post-discharge period may prevent the relatively high levels of non-adherence that appear to become established by 6 months following an ACS.

Keywords: Adherence, Acute coronary syndrome, Psychological, Intention

Introduction

Medication adherence refers to the extent to which taking medication corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider [1]. Non-adherence is a particular problem in patients diagnosed with conditions related to cardiovascular disease (CVD), as long-term pharmacotherapy is a central part of the medical management of CVD [2]. A recent meta-analysis of 44 cohort studies consisting of almost 2 million participants found that 60% had good adherence (≥ 80%) to CVD medications [3]. This study was also able to estimate that approximately 9% of all CVD acute events may be attributable to poor adherence and therefore confirms the findings from earlier reviews indicating that non-adherence is a significant barrier to reducing the public health impact of CVD [4,5].

Medication adherence has received intensive study from both behavioural and clinical scientists for several decades now [6] and both theories of medication taking [7–9] and measurement strategies have developed in this time [10,11], however this has not led to the identification of standardised and reliable intervention techniques that can improve medication adherence [12]. One possible explanation for the limited efficacy of interventions is the imprecise characterisation of non-adherence in terms of the stability of the problem and the extent to which this behaviour is intentional as opposed to unintentional [13]. Intentional non-adherence refers to non-adherence that is deliberate and largely associated with patient motivation whereas unintentional non-adherence is non-adherence that is largely driven by a lack of capacity or resources to take medications [14]. However it is important to acknowledge that the reasons underlying intentional and unintentional non-adherence are not entirely independent in that certain types of unintentional non-adherence e.g. forgetting, are logically more likely when motivation for medication is low.

Studies of non-adherence to medication following acute CVD events such as acute coronary syndrome (ACS) have often neglected the immediate discharge period following acute treatment. The failure of much of this literature to disaggregate the temporal stability and nature of non-adherence is problematic, as these represent distinct behavioural phenomena that may have different determinants [13,15] and therefore require different intervention strategies [16]. It is important therefore to know what is the extent of these types of non-adherence in the immediate and post-discharge period. This paper therefore aims to add important descriptive information on medication adherence by answering 2 questions:

-

1.

What is the extent of intentional and unintentional non-adherence to medication in the year following ACS?

-

2.

Does the overall rate of medication non-adherence change significantly in the year following an ACS?

Methods

Participants were 223 patients with ACS admitted to St. George's Hospital in South London between June 2007 and October 2008 taking part in a larger study of biological factors and emotional adjustment (N = 298), the Tracking Recovery after Acute Coronary Events (TRACE) study which is reported in detail elsewhere [17,18]. The TRACE study was approved by the Wandsworth Research Ethics Committee, and written consent was obtained from all participants.

Medication adherence was measured using a 5 item scale, the Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS-5) [19], which is a widely used measure that has established reliability and validity [8,9,20]. Respondents indicate how often they engage in the five non-adherent behaviours on a 1–5 frequency scale (always, often, sometimes, rarely, never). Cronbach's α for this scale averaged at 0.64 in the present study. As item 1 (I forget to take my medicines) referred to unintentional non-adherence and items 2–5 refer to intentional non-adherence, two separate measures could be derived from this scale. Categorical non-adherence was defined as reporting any non-adherence on the MARS. Dichotomizing self-reported adherence in this way was for descriptive purposes and this approach is often taken in this literature due to the skewed, non-normal distributions of medication adherence data [9] and the potential for under-reporting for non-adherence [1].

Patients were interviewed in their homes an average of 21.6 days following admission. Clinical details were obtained from medical notes about cardiovascular history, clinical factors during admission and management. A range of psychological measures and standard socio-demographic measures including age, gender, marital status, education and ethnicity were recorded. Follow-up measures of medication adherence using the MARS were collected by postal questionnaire at approximately 6 and 12 months following initial discharge.

In order to compare those providing medication adherence data at 12 months with those that were recruited into the larger study at baseline independent samples t-tests were used to test for significant differences in means for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for non-independence for categorical variables. As the continuous medication non-adherence data from the MARS was significantly negatively skewed at the three time points Wilcoxon Signed Rank Tests were used to test whether there was a significant difference in medication non-adherence over time.

Results

The characteristics of the sample at 12 months are summarized in Table 1. Non-responders were more likely to be from ethnic minority groups and to have higher levels of social deprivation. There were no other significant differences observed between those recruited in the larger study [17,18] and those who provided medication adherence data at 12 months. Fig. 1 presents the breakdown of medication non-adherence for all participants included at each time point by total, intentional and unintentional non-adherence at 2 weeks, 6 months and 12 months post-discharge. The Wilcoxon Signed Rank Tests revealed that there was a significant increase in total medication non-adherence (measured continuously) between 2 weeks and 6 months (Z = − 5.163, P < 0.01) and between 2 weeks and 12 months (Z = − 10.34, P < 0.01). There was no significant difference between medication adherence (measured continuously) at 6 and 12 months (Z = − 0.29, P = 0.77).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample at 12 month follow-up

| 12 month sample n = 136 |

Non-responders at 12 months n = 162 |

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | n (%) | Mean (SD) | n (%) | ||

| Demographic factors | |||||

| Age | 61.19 (11.12) | 59.28 (11.91) | .16 | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Men | 116 (85) | 134 (83) | |||

| Women | 20 (15) | 28 (17) | .55 | ||

| Marital status (married) | 94 (69) | 109 (67) | .74 | ||

| Educational attainment | |||||

| Basic | 72 (53) | 86 (53) | |||

| Secondary | 43 (32) | 50 (31) | |||

| Degree | 20 (15) | 26 (16) | .95 | ||

| Ethnicity (white) | 120 (88) | 127 (78) | .03 | ||

| Social deprivation | |||||

| Low | 101 (75) | 87 (54) | |||

| Medium | 22 (16) | 48 (30) | |||

| High | 11 (8) | 25 (16) | < .01 | ||

| Clinical factors | |||||

| ACS type | |||||

| STEMI | 118 (87) | 142 (88) | |||

| NSTEMI/UA | 18 (13) | 20 (12) | .82 | ||

| Grace score | 94.79 (25.61) | 91.22 (29.36) | .27 | ||

| Previous MI | 20 (15) | 19 (12) | .46 | ||

Fig. 1.

Percentage of patients reporting medication non-adherence by type in the year following acute coronary syndrome.

Discussion

These results show that unintentional non-adherence may be the primary form of non-adherence in the year following an ACS, as this type of non-adherence was reported over 3 and a half times more frequently at 6 and 12 months. Other studies of older adults with multiple co-morbidities [15] and patients with hypertension [13] have also identified similar patterns of non-adherence to medication. The study also revealed that overall non-adherence was higher than estimates from more objective measurement [3] and that non-adherence significantly increases between the immediate discharge period and at 6 months before stabilizing.

These findings suggest that behaviour change techniques that focus on establishing a medication taking routine or habit [16] early in the discharge period might help reduce the relatively high levels of non-adherence that appear to become established by 6 months. Recent evidence in the context of a hypertension medication regimen has shown that medication ‘habit strength’ was the strongest predictor of a range of self-report and electronic monitoring of medication adherence [20]. It is possible therefore that strengthening medication taking habits may offer a counterbalance against higher level cognitive processes or fluctuations in emotional distress that could interfere with adherence [16], however further empirical investigation is required to reliably test this hypothesis.

There are a number of caveats that should be considered in relation to this study. First, the self-report measure of non-adherence has a number of obvious limitations and in particular the likelihood of reporting biases [2] e.g. social desirability or recall biases. Indeed it is possible that social desirability bias was more likely at the first two week measurement point due to the nature of the in home face-to-face interview. It is generally agreed however that all available adherence measures have their strengths and limitations, therefore there is no consensus on what constitutes a gold standard [1], nor is it clear how non-adherence intentionality can be assessed without self-report. Second, this is a relatively small sample of ACS patients from a single centre in a publically funded national health service, therefore there are limitations in terms of external validity. Finally there was evidence of attrition bias in the sample with those from ethnic minority groups and those living in greater social deprivation more likely to be non-responders at 12 months.

Nevertheless this is the first study to look at levels of intentional and unintentional non-adherence in ACS patients and these results provide new information on the extent and stability of intentional and non-intentional non-adherence in the year following acute treatment. In particular the current findings would suggest that the future design of interventions to improve adherence to medication should pay particular attention to unintentional aspects of non-adherence and the selection of particular behaviour change techniques [21] that address this specific issue may lead to the design of more effective interventions than currently exist [12].

Conflict of interest

There are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

Acknowledgments

The original TRACE study was supported by the British Heart Foundation (RG/05/006) and was partly funded by a grant (PBBE1-117004) from the Swiss National Foundation to Dr Nadine Messerli-Bürgy. The British Heart Foundation and the Swiss National Foundation had no role in the design, analysis or interpretation of this study. The first author (GJM) has received funds in 2013 from Lilly Diabetes to give a presentation to health care professionals on medication adherence.

References

- 1.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Drug therapy — adherence to medication. New Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kronish IM, Ye SQ. Adherence to cardiovascular medications: lessons learned and future directions. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;55:590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chowdhury R, Khan H, Heydon E, Shroufi A, Fahimi S, Moore C. Adherence to cardiovascular therapy: a meta-analysis of prevalence and clinical consequences. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2940–2948. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naderi SH, Bestwick JP, Wald DS. Adherence to drugs that prevent cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis on 376,162 patients. Am J Med. 2012;125:882–887. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiMatteo MR, Giordani PJ, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes — a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2002;40:794–811. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients' adherence to medical recommendations — a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004;42:200–209. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114908.90348.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.French DP, Wade AN, Farmer AJ. Predicting self-care behaviours of patients with type 2 diabetes: the importance of beliefs about behaviour, not just beliefs about illness. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74:327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiMatteo MR, Haskard-Zolnierek KB, Martin LR. Improving patient adherence: a three-factor model to guide practice. Health Psychol Rev. 2012;6:74–91. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horne R, Chapman SC, Parham R, Freemantle N, Forbes A, Cooper V. Understanding patients' adherence-related beliefs about medicines prescribed for long-term conditions: a meta-analytic review of the necessity–concerns framework. Plos One. 2013;8:e80633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voils CI, Maciejewski ML, Hoyle RH, Reeve BB, Gallagher P, Bryson CL. Initial validation of a self-report measure of the extent of and reasons for medication nonadherence. Med Care. 2012;50:1013–1019. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318269e121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garber MC, Nau DP, Erickson SR, Aikens JE, Lawrence JB. The concordance of self-report with other measures of medication adherence — a summary of the literature. Med Care. 2004;42:649–652. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000129496.05898.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowry KP, Dudley TK, Oddone EZ, Bosworth HB. Intentional and unintentional nonadherence to anti hypertensive medication. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:1198–1203. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clifford S, Barber N, Horne R. Understanding different beliefs held by adherers, unintentional nonadherers, and intentional nonadherers: application of the necessity–concerns frarnework. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuz B, Marx C, Wurm S, Warner LM, Ziegelmann JP, Schwarzer R. Medication beliefs predict medication adherence in older adults with multiple illnesses. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Carroll RE, Chambers JA, Dennis M, Sudlow C, Johnston M. Improving adherence to medication in stroke survivors: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:358–368. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9515-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steptoe A, Molloy GJ, Messerly-Burgy N, Wikman A, Randall G, Perkins-Porras L. Emotional triggering and low socio-economic status as determinants of depression following acute coronary syndrome. Psychol Med. 2011;14:1857–1866. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steptoe A, Molloy GJ, Messerli-Burgy N, Wikman A, Randall G, Perkins-Porras L. Fear of dying and inflammation following acute coronary syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2405–2411. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horne R, Weinman J. Patients' beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555–567. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips LA, Leventhal H, Leventhal EA. Assessing theoretical predictors of long-term medication adherence: patients' treatment-related beliefs, experiential feedback and habit development. Psychol Health. 2013;28:1135–1151. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2013.793798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:81–95. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]