Abstract

Purpose:

To describe the use of online seminars (webinars) to improve learning experience for medical residents and fostering critical thinking.

Materials and Methods:

Sixty-one online seminars (webinars) for residents were developed from April 2012 to February 2013. Residents attended the lectures in the same room as the presenter or from distant locations. Residents interacted with the presenter using their personal computers, tablets, or smartphones. They were able to ask questions and answer the instructor's multiple choice or open-ended questions. The lecture dynamics consisted of: (1) The presentation of a clinical case by an expert on the clinical topic; (2) the instructor asked open-ended and multiple-choice questions about the problem-resolution process; (3) participants responded questions individually; (4) participants received feedback on their answers; (5) a brief conference was given on the learning objectives and the content, also fostering interactive participation; (6) lectures were complemented with work documents.

Results:

This method allowed for exploration of learning of scientific knowledge and the acquisition of other medical competences (such as patient care, interpersonal and communication skills, and professionalism). The question-and-answer activity and immediate feedback gave attendees the chance to participate actively in the conference, reflect on the topic, correct conceptual errors, and exercise critical thinking. All these factors are necessary for learning.

Conclusions:

This modality, which facilitates interaction, active participation, and immediate feedback, could allow learners to acquire knowledge more effectively.

Keywords: Generational Learning, New Technologies, Residents, Webinars

INTRODUCTION

Studies published on generational learning describe the present generation of people between 25 and 35 years of age (“millennial” or “generation Y”, born between 1980 and 2000) as having the following traits: An orientation to collaborative and team work,1 comfort with technology (particularly Internet),2,3,4 and multitasking preferences (such as watching TV, browsing on the internet, and sending phone text messages simultaneously).5

Adult learning principles highlight the importance of relevant content to predispose learning: Adults will be motivated to study a subject when they are able to see their usefulness in their daily work.6 Likewise, formative feedback,7,8,9 and reflection10,11,12 are currently considered key in learning and acquiring new abilities. Feedback and reflection are also necessary for developing critical thinking.13

Several authors recommend using the new teaching technologies for the new generations of professionals.14,15,16,17,18,19 The combination of clinical cases, explanation of content, and interactivity has been described as an appealing strategy for millennials. This format allows students to use previous knowledge, receive immediate formative feedback, and reflect on their mistakes.

The purpose of this paper is to describe a strategy combining in-person classes with online activities intended to improve learning and develop critical thinking.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

At the residency program of the Ophthalmology Department of Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, 61 online seminars (webinars or web seminars) for residents were delivered from April 2012 to February 2013. Adobe Connect® software was used for the development of webinars. The content was planned according to the residency program curriculum.

Instructors were content experts who prepared bibliographical updates of the subject presented. The content and pedagogical quality of presentation was supervised by an expert in medical education, e-learning, and instructional design (EM). Presentations were reviewed to ensure inclusion of adequately defined learning objectives, number and quality of interactivities, and a correct use of images, videos, and words.

The webinars dynamics consisted of:

The presentation of one or several clinical cases by the subject expert at the beginning of the event. The majority of cases were real, but occasionally fictitious cases were also developed

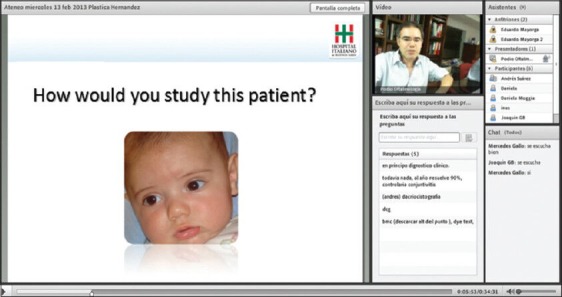

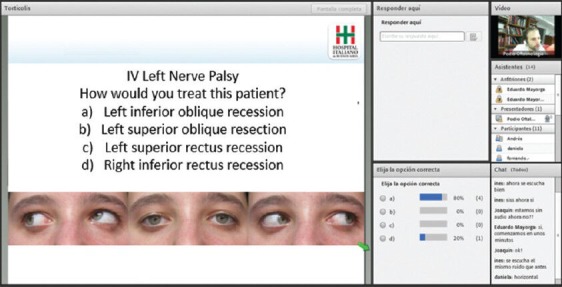

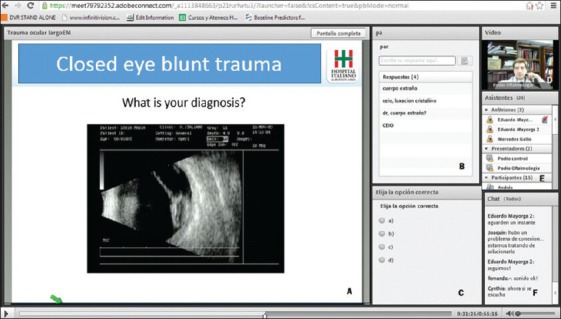

Following the case presentation the instructor asked questions to the residents. Questions were open and/or multiple-choice about decisions for the problem-resolution process [Figures 1 and 2]. The digital platform allowed hiding the answer window, so residents could respond individually without knowing what their partners were answering [Figure 3]

Once all the residents had answered, the speaker allowed the residents to view the answers and discuss them. For multiple-choice questions the instructor showed the distribution of answers based on quality and percentage. Participants received feedback on their answers

Learning objectives were then exposed and the content was developed. Active participation through questions was encouraged at this stage

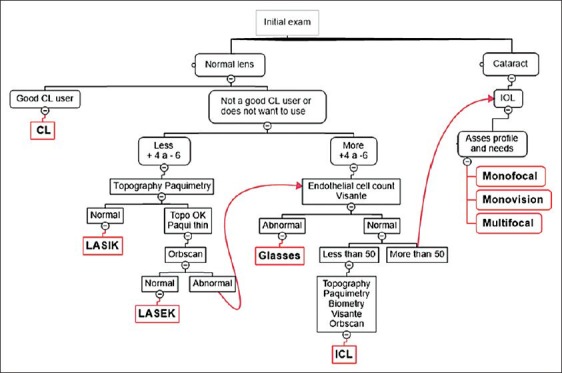

All classes were complemented with work documents (diagnosis and treatment algorithms, links to extended information on the subject, original papers from international journals, etc.) [Figure 4]. Work documents allowed students to review the main points, have some help for the application of the content that was learnt, and enhance knowledge of the topic

Time for questions and answers was allotted at the end of the class

Figure 1.

Example of an open question

Figure 2.

Example of a multiple-choice question

Figure 3.

Webinar display using Adobe Connect platform. (a) Class transmission screen. (b) Open-question panel. (c) Multiple-choice question panel. (d) Camera focusing on presenter. (e) List of attendants. (f) Chat window

Figure 4.

Example of a work document given at a refractive surgery class

Two of the authors (EM and JB) coordinated the transmission of webinars and were responsible for uploading the classes on the internet. Residents logged on individually by using their computers or the department's computers.

RESULTS

This method allowed for the exploration of the acquisition of scientific knowledge and other medical competences (such as patient care, interpersonal and communication abilities, professionalism, and system-based practice) in residents.

The use of clinical cases and updated theoretical and practical content ensured relevance and articulation with the resident's daily practice.

The different kinds of questions and answers (open and multiple-choice) and the immediate feedback gave residents the possibility of participating actively in the conference. They were able to use their knowledge of the subject matter, to reflect and correct conceptual errors, and to exercise critical thinking. Hiding the answers until all had responded encouraged participation of all the residents.

The use of Adobe Connect software was simple for teachers and residents. Connectivity or sound problems were rare, and usually related to local network problems.

DISCUSSION

A “generational cohort” is a term used to include individuals born in the same period of time (generally 15-20 years) who share key life experiences (including demographic trends, historical events, pastimes and entertaining, public heroes, work experiences, etc.).15 Studies classify generations as from the XX century into traditionalists (born 1933-1946), baby boomers (1946-1964), generation X (1964-1980), generation Y (1980-2000), and generation Z (+2000). This classification is used in studies published in the United States and Europe, considering World War II as a reference for separation between the first two generations. Globalization has made the characteristics of the last three generations more uniform among countries.

Currently, the majority of ophthalmology residents are about 25-35 years of age, which includes them in generation Y, also called the millennial generation. While there are individual differences, studies published on generational learning1,2,3,4,5 describe some characteristics of this generation including:

Their orientation to collaborative and team work

Their comfort with and preference for technology (particularly Internet)

Their preference for multitasking (performance of multiple tasks at the same time, such as watching television, browsing on the internet, and sending phone text messages simultaneously).

Several authors recommend the use of specific strategies in teaching new generations of professionals. In a literature review on inter-generational differences performed by a group of almost 100 residency program directors and other emergency faculty, Moreno-Walton et al.,3 present a series of educational recommendations to teach new generations of residents. These recommendations include: Setting clear rules, assessing and providing frequent feedback, defining clear objectives and their importance, helping them develop their sense of responsibility and basic values in medical practice, being consistent in matters of professionalism, and incorporating peer evaluations. Likewise, the use of technological resources is recommended to improve classes. Examples of these resources are:

Case-based conferences that could bring a practical perspective to the material taught

Audience response systems to provide immediate feedback to participants

Simulations

Internet-based resources (such as podcasts and live webinars, etc.).

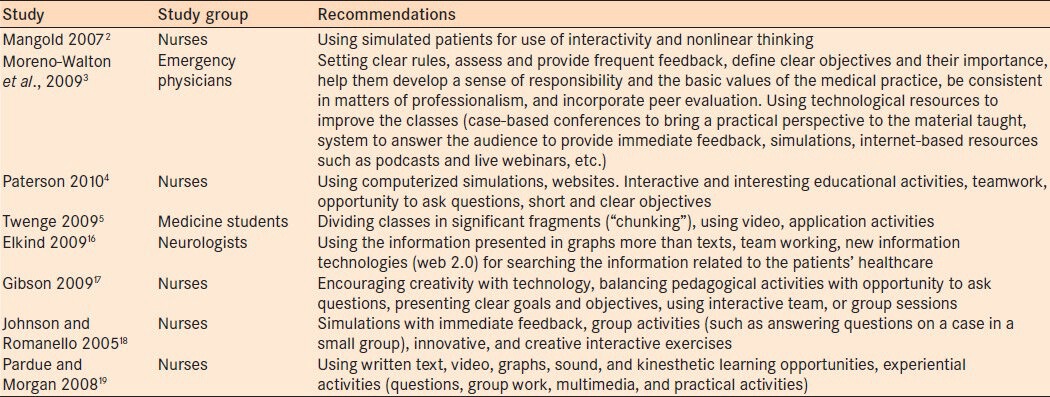

Other authors2,3,4,5,16,17,18,19 provide similar recommendations for teaching different groups of healthcare workers at this stage [Table 1].

Table 1.

Recommendations for teaching the millennial generation of learners

The principles for adult learning shape the way educational strategies must be planned when teaching individuals in this age group. Malcolm Knowles, the father of andragogy (the science of teaching adults) explains6 that adults:

Need to know why they should learn something before embarking to learn it

Are willing to learn things they need to be able to effectively handle daily life situations; and

Their motivation to learning depends on whether they perceive the learning will help them develop tasks or solve problems they face in daily life.

Adults will learn new knowledge, understanding, abilities, values, and attitudes more effectively when they are presented in the context of application of their real life situation. These principles guide the development of the educational process for adults, indicating the use of experience-based learning techniques characterized by:

Possible practical application

Being inquisitive and reasoned

Being participative

Having clearly defined objectives

Situated in the context of daily life and

Including provision of formative feedback.

Several authors have also studied the importance of formative feedback. Anders Ericsson points out the value of feedback in the frequent practice of skills to become an expert, especially in learning health sciences.7,8 In a systematic review of 220 studies that assessed the impact of feedback in the clinical development of physicians, Veloski et al.,9 found that feedback has a positive effect in changing clinical performance.

The value of reflection on each individual's own practice has been suggested by several authors. Reflection is necessary to learn from experience, spot mistakes and correct them, and continually improve in practice.10,11,12 In a systematic review on reflection and reflective practice in education of science professions, Mann et al.,12 report the finding of observational studies suggesting the benefit of reflection on medical practice. The ability to create associations and integrating information could result in deeper learning and better comprehension of the context.

Studying through clinical presentations could stimulate the development of critical thinking in the physician. Critical thinking has been defined as the ability to improve thinking about an individual, content, or problem; by analyzing it smartly; assessing it; and reconstructing it.13 This skill is necessary to resolve complex problems. The critical thinker:

Collects information (through all senses, verbal and/or written expressions, reflection, observation, experience, and reasoning)

Asks vital and clearly stated questions

Obtains and assesses relevant information

Uses abstract ideas that are interpreted and employed with efficacy

Reaches well-reasoned conclusions and solutions

Tests the results against relevant criteria and standards

Uses alternative thinking strategies according to the problem/needs

Assesses all assumptions, implications, and practical consequences; and

Communicates effectively with others to generate solutions to complex problems.20

The study method through clinical presentations fosters students to get involved in advanced strategies of scheme inductive reasoning, which is used by experts in the resolution of cases.

The method of teaching through webinars we describe in this paper met several of the advantages mentioned above:

Clinical cases were used to foster questioning, application of previously acquired knowledge, discovery of missing knowledge, and critical thinking

The subject experts provided residents with immediate feedback, in order to reinforce what they knew and correct mistakes

Clearly defined learning objectives of practical application were included in all presentations

The content was on relevant topics applicable to daily practice

Seminars were coordinated and given by subject experts, with updated bibliography and based on the best evidence available

Webinars allowed exploring and teaching not only clinical knowledge, but also other competences (such professionalism, system-based practice, communication abilities, and practice-based improvement)

They were supervised by an expert in medical education, e-learning, and instructional design (EM); assuring their educational quality

They included internet-based technology as a novel and interesting strategy for the generation of millennials that enjoy new technologies.

The active participation of residents was also favored by this method. In traditional lectures, the teacher asks questions and one or two students respond. When this happens, the teacher cannot know if the rest of the students had the same answer or a different response. Opposite to this, the simultaneous method of multiple-choice and open questions online enabled the determination of the knowledge status of all participants, as the answers were hidden until everybody had responded.

Another difference with traditional lecture was that usually only those who know or are sure of the correct answer are the ones who reply to open questions. This new method gave all the students a chance to respond.

Finally, the questions allowed self-evaluation of residents on subjects, which would stimulate their interest.

The limitation of this paper is that learning by this method was not compared to other methods. Joshi et al.,21 conducted a randomized controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of webinars with participative learning (in which students read the material on their own) to teaching essential newborn care to a group of 59 nurses. They assessed acquisition of knowledge (through an objective structured questionnaire) and abilities (through four structured clinical exams - objective structured clinical examination (OSCE)) by assigning them a pre- and post-intervention score. They found that acquisition of knowledge and abilities was significant and similar in both groups. It would be of educational interest to compare learning through this method with the traditional class method and questioning without the use of this technology.

CONCLUSIONS

We believe this modality; which makes interaction, active participation, and immediate feedback easier; could make acquisition of knowledge more effective. It could also facilitate training in medical competences and development of the critical thinking necessary for correct decision-making. It is an attractive format for the new generations of residents, who appreciate inclusion of new technologies in their instruction. The design should consider the principles applicable to adult learning (with clear objectives and content relevant to practice) to make acquisition of knowledge easier.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilson M, Gerber LE. How generational theory can improve teaching: Strategies for working with the millennials. Curr Teach Learn. 2008;1:29–44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mangold K. Educating a new generation. Teaching baby boomer faculty about millennial students. Nurse Educ. 2007;32:21–3. doi: 10.1097/00006223-200701000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moreno-Walton L, Brunett P, Akhtar S, DeBlieux PM. Teaching across the generation gap: A consensus from the Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors 2009 academic assembly. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:S19–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paterson T. Generational considerations in providing critical care education. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2010;33:67–74. doi: 10.1097/CNQ.0b013e3181c8dfa8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Twenge JM. Generational changes and their impact in the classroom: Teaching Generation Me. Med Educ. 2009;43:398–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knowles M, Holton EF, III, Swanson RA. 7th ed. Burlington (MA): Elsevier; 2011. The Adult Learner. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ericsson KA, Krampe RT, Tesch-Römer C. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol Rev. 1993;100:363–406. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ericsson KA. Acad Med. 6th Ed. Vol. 79. Butterworth-Heinemann; 2004. Deliberate practice and the acquisition and maintenance of expert performance in medicine and related domains; pp. S70–81. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veloski J, Boex JR, Grasberger MJ, Evans A, Wolfson DB. Systematic review of the literature on assessment, feedback and physicians’ clinical performance: BEME Guide No 7. Med Teach. 2006;28:117–28. doi: 10.1080/01421590600622665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schön DA. The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. [place unknown] Basic Books. 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schön DA. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 1990. Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mann K, Gordon J, MacLeod A. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: A systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2009;14:595–621. doi: 10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Facione PA. The California Academic Press; 1990. Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for educational assessment and instruction. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coates J. River Falls (WI): LERN Books; 2007. Generational Learning Styles. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weston M. Coaching generations in the workplace. Nurs Adm Q. 2001;25:11–21. doi: 10.1097/00006216-200101000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elkind MS. Teaching the next generation of neurologists. Neurology. 2009;72:657–63. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000342516.08077.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibson SE. Intergenerational communication in the classroom: Recommendations for successful teacher-student relationships. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2009;30:37–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson SA, Romanello ML. Generational diversity: Teaching and learning approaches. Nurse Educ. 2005;30:212–6. doi: 10.1097/00006223-200509000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pardue KT, Morgan P. Millennials considered: A new generation, new approaches and implications for nursing education. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2008;29:74–9. doi: 10.1097/00024776-200803000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harasym PH, Tasi TC, Hemmati P. Current trends in developing medical students’ critical thinking abilities. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2008;24:341–55. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(08)70131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joshi P, Thukral A, Joshi M, Deorari AK, Vatsa M. Comparing the effectiveness of webinars and participatory learning on essential newborn care (ENBC) in the class room in terms of acquisition of knowledge and skills of student nurses: A randomized controlled trial. Indian J Pediatr. 2013;80:168–70. doi: 10.1007/s12098-012-0742-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]