Abstract

Context:

Psoriasis has an impact on psychology of the patients. There is a dearth of studies regarding this field in eastern India.

Aims and Objectives:

The primary objective of this study is to evaluate the psychiatric morbidity in psoriasis and secondary objective is to assess the morbidity in all eight dimensions of psychosocial and physical aspects, i.e. cognitive, social, discomfort, limitations, depression, fear, embarrassment and anger.

Settings and Design:

Institutional based case control study.

Materials and Methods:

Forty-eight patients of psoriasis and equal number of healthy controls were included in the study. Self-reporting questionnaire-24 (SRQ-24) and skindex (A 61-item survey questionnaire) were used to assess the psychiatric morbidity in both groups.

Statistical Analysis Used:

“MedCalc version 10.2.0.0” (by Acacialaan 22, B-8400, Ostend, Belgium) was used as statistical software. Chi-square test was used as a test of significance.

Results:

The SRQ assessed psychiatric morbidity in the study group was 62.5%, compared with 18.5% in the control group. This difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001). Guttate psoriasis had maximum association with psychiatric morbidity (100%), followed by plaque type (63.6%) and palmoplantar type (42.8%). According to the skindex, the most common psychiatric morbidity in psoriasis patients was anger (58.3%), followed by discomfort (52.08%), social problem (52.08%), cognitive impairment (50%), embarrassment (50%), physical limitation (47.91%), fear (47.91%) and depression (43.75%). The skindex observed psychiatric morbidity among the case and control group was statistically significant for all the parameters (P < 0.0001).

Conclusion:

Psoriasis has a high degree of psychiatric morbidity and the extent of this co-morbidity is even greater than hitherto thought of.

Keywords: Psoriasis, psychiatric morbidity, self-reporting questionnaire-24, skindex

Introduction

Psoriasis is one of the most common dermatological disorders in India. The chronicity of the disease has a great impact on the psychology of the patient. It can have a significant negative impact on the physical, emotional and psychosocial well-being of affected patients.[1,2] Patients with psoriasis have a reduction in their quality-of-life similar to worse patients with other chronic diseases, such as an ischemic heart disease and diabetes.[2] Psychological distress, in the form of excessive worrying, has a significant and detrimental effect on treatment outcome in patients with psoriasis.[3] It affects 1.4-2.0% of the population and comprises 2.6% of skin-related visits to primary care physicians or between 0.3% and 0.6% of all visits to family physicians.[1] The field of psycho-dermatology has developed as a result of increased interest and understanding of the relationship between skin disease and various psychological factors.[1] Historically, psychosomatic dermatology can only have existed since the term “psychosomatic” was introduced in 1818 by Heinroth.[4]

Psychosomatic dermatology in the narrower sense encompasses every aspect of intrapersonal and interpersonal problems triggered by skin diseases and the psychosomatic mechanisms of eliciting or coping with dermatoses. Psychosomatic dermatology addresses skin diseases in which psychogenic causes, consequences or concomitant circumstances have an essential and therapeutically important influence.[4]

Based on research, results now available and on practical experience, classification in psychosomatic dermatology can now be differentiated in the following ways: (1) Dermatoses of primarily psychological genesis, (2) dermatoses with a multifactorial basis, whose course is subject to emotional influences (psychosomatic diseases), (3) psychiatric disorders secondary to serious or disfiguring dermatoses (somatopsychic illnesses).

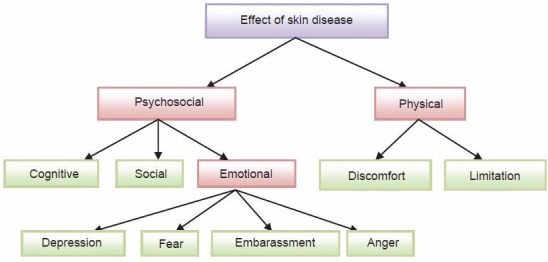

Based on published works on psychosocial aspects of different dermatologic conditions and directed focus sessions with patients, physicians and nurses who care for patients with skin problems, Chren et al. constructed a conceptual framework for the subjective effects of skin disease on patients' quality-of-life [Figure 1]. These effects have two major domains: Psychosocial and physical. Within these domains, they identified five dimensions: Psychosocial effects that are cognitive, social or emotional and physical effects that are related to physical discomfort or limitations in physical functions. Within the emotional dimension, they included the sub-dimensions of depression, fear, embarrassment and anger.[5]

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for the effects of skin disease on patients' quality of life. This hypothesis was based on literature review and directed interviews with the patients with skin disease and clinicians who care for them. The constructs which are addressed by the skindex are highlighted by green boxes

By using the above mentioned dimensions in two domains; Chren et al. developed an instrument to measure the effects of skin disease in a patient's life for assessing psychosocial morbidities in psoriasis patients.

Hence it is clear that there is a deep correlation between the psychology of the patient and the natural course and outcome of the disease. There is a lack of studies conducted in this field in the eastern part of India.

Aims and Objectives

To assess the psychiatric morbidity among treatment seeking patients of psoriasis and to evaluate the morbidity in all eight dimensions of psychosocial and physical aspects, i.e. cognitive, social, discomfort, limitations, depression, fear, embarrassment and anger in a psoriasis patient in a tertiary care center, in an attempt to throw some light on the importance of the same.

Materials and Methods

An institutional based case control study done in a Tertiary Care Hospital of Eastern India from January 2011 to December 2012 with 48 cases of psoriasis and a similar number of age (±2 years) and sex matched control.

Inclusion criteria

Psoriasis is diagnosed by consultant dermatologist.

Age > 18 years.

Both sexes.

Informed consent.

Age and sex matched control.

Must understand and read and write Bengali.

Exclusion criteria

The patient should not have any other comorbid general medical illness.

In patient group psychiatric illness that starts before the onset of psoriasis, i.e., the psychiatric illness is not a result of psoriatic illness.

Patients who are unwilling to participate in the study.

The control group should be free from psoriasis.

Self-reporting questionnaire-24 (SRQ-24) and skindex (A 61-item self-administered survey questionnaire to assess the quality-of-life of patients of dermatological disorder on the aforementioned eight scales) was used as a study tool. Clinical profile was determined. Data were collected in a pre-designed case data sheet and were analyzed with appropriate statistical software. Chi-squared test or Fischer exact test or Monte Carlo approximation was applied as statistical tool.

Results

Over the period of 1 year, about 48 patients of psoriasis and similar number of age (±2 years) and sex matched healthy controls were chosen for the study from the patients attending the dermatology outpatient department in a tertiary care hospital in Kolkata.

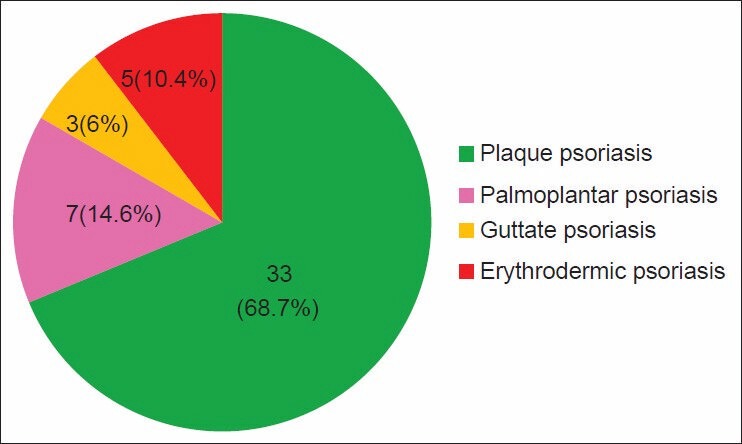

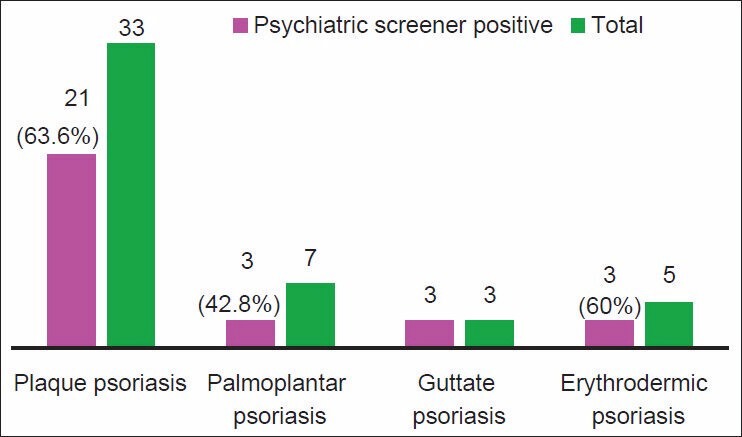

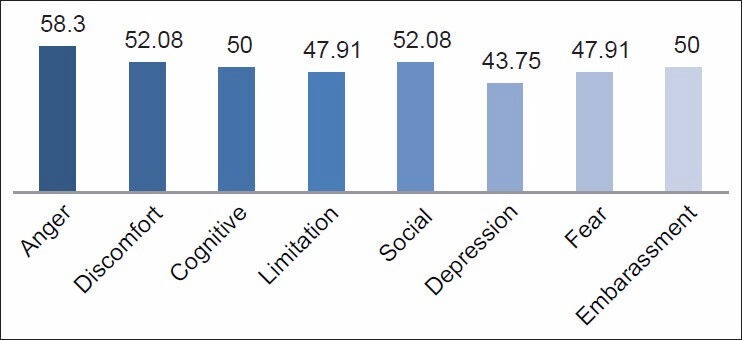

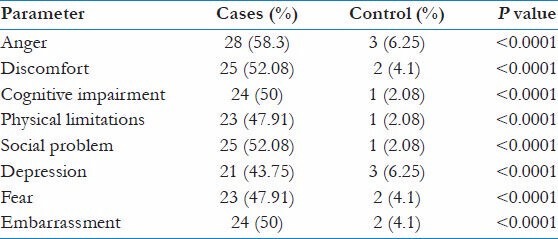

The age of the psoriasis patients ranged from 21 to 67 with a mean of 42.92 (standard deviation [SD] = 12.20). In the control group (n = 44), the age ranged from 24 to 65 with a mean of 39.98 (SD = 11.45). In both groups, 31 cases were male and 17 were female with a male to female ratio of 1.82:1. Most of the patients of the study was suffering from plaque psoriasis (68.7%) followed by palmoplantar psoriasis (14.4%), erythrodermic psoriasis (10.4%) and guttate psoriasis (6%) [Figure 2]. In the study population psychiatric screener was positive in 62.5% of patients while in the control group psychiatric screener was positive in 18.5%. This difference was statistically significant (P < 0.0001). It was seen that, 63.6% of the plaque psoriasis patients had positive psychiatric screener result. Among all types palmoplantar variety and erythrodermic variety had got lowest psychiatric morbidity (42.8%) and guttate had the highest prevalence of psychiatric screener positivity (100%) [Figure 3]. According to the skindex, the commonest psychiatric morbidity in psoriasis patients was anger (58.3%), followed by discomfort (52.08%), social problem (52.08%), cognitive impairment (50%), embarrassment (50%), physical limitation (47.91%), fear (47.91%) and depression (43.75%) [Figure 4]. Whereas in the control group, the psychiatric morbidities observed were anger (6.25%), discomfort (4.1%), cognitive impairment (2.08%), physical limitation was (2.08%), social problem was (2.08%), depression (6.25%), fear was (4.1%) and embarrassment was (4.1%). The above differences in the two groups were found to be statistically significant for all the parameters among the cases and controls [Table 1].

Figure 2.

Prevalence of the types of psoriasis

Figure 3.

Psychiatric screener positively in the psoriasis group

Figure 4.

Mean skindex score in psoriasis cases (%)

Table 1.

Comparison of the cases and controls in the eight dimensions of psychosocial and physical morbidity

Discussion

Psoriasis is a genetically determined chronic inflammatory disease, that is associated with different co-morbidities such as metabolic abnormalities, cardiovascular disease and psychiatric ailments.[6] All ages including pediatric population[7] and sexes are prone to develop psychiatric problems.

The tool used for screening purpose in this study was SRQ. This 24 item questionnaire is comparable to General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) 12 or 28 for assessing psychiatric morbidity.[8] GHQ is most commonly used by different studies, but this scale is unable to detect psychotic phenomena.[9]

For measuring quality-of-life in psoriasis patients, here skindex-61 questionnaire was used. This scale uses eight dimensions for assessing quality -of -life in a patient with dermatologic disorder. The results of the present study reveal that the mean age of psoriasis patients were 42.92 years and the mean age of the control group were 39.89 years. This suggests the groups were well age matched as the difference in mean age and (SD = 12.20 in psoriasis group and 11.45 in the control group was not significant). In both groups, 31 cases were male and 17 were female with a male to female ratio of 1.82:1. The less number of female in both groups can be explained by the socio cultural background of our country. Here, females are less treatment seeker than men and hence they attend less in hospital outdoor clinic.

The SRQ assessed psychiatric morbidity of 62.5%, was found to be higher compared to 24.3% of the GHQ assessed psychiatric morbidity reported for psoriasis out-patients at one center in India (Mattoo et al., 2005).[10] However, our study was comparable with most other studies reporting rates of 58-62% for outpatients of all dermatological disorders including psoriasis (Akay et al.,[11] 2002; Bharath et al.,[12] 1997; Esposito et al.,[13] 2006; Sampogna et al.[14] , 2004).

All the skindex dimensional values are higher in positive screener result persons. And these values are highly statistically significant. This result is very much predictable. As the quality-of-life is worse in patients having psychiatric co-morbidity, the poor skindex outcome in a patient with positive SRQ result is inevitable.

Kumar et al. in a pilot study on psychiatric morbidity of psoriasis described that 90% of psoriasis patients had some depression.[15] Anxiety and depression were two major psychiatric co-morbidities as depicted by Han et al.[16] A comparative study of psychiatric morbidities of psoriasis and pemphigus showed that depression and adjustment disorder were the major psychiatric ailments.[17] In the present study, anger is the most common psychiatric co-morbidities, followed by discomfort, social problem, fear, depression, etc.

Co-morbid psychiatric illness was highly prevalent in psoriasis group compared with the control group according to SRQ-24 screener. This difference was statistically significant too (P < 0.0001). Among different types of psoriasis, guttate was associated with highest psychiatric co-morbidity (100%) followed by plaque, erythrodermic and palmoplantar was associated with lowest co-morbidity. Severity of psoriasis was associated significantly higher psychiatric co-morbidity as well as poorer quality- of-life among psoriasis patients as depicted by the skindex-61. This result was statistically significant. The age, duration of illness, income, sex, presence of relapses and drug treatments or any other clinical or demographical variables except hospitalization were associated to psychiatric co-morbidity.

Conclusion

To conclude, we mention that our study showed, in consonance with previous endeavours that, dermatological conditions, especially psoriasis, have a high degree of psychiatric morbidity and the extent of this co-morbidity is even greater than hitherto thought of. This study have addressed to different factors that can influence the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in this disorders and found some interesting trends, which certainly opened a vista for further study in this regard.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Barankin B, DeKoven J. Psychosocial effect of common skin diseases. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:712–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: Epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(Suppl 2):ii18–23. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.033217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fortune DG, Richards HL, Kirby B, McElhone K, Markham T, Rogers S, et al. Psychological distress impairs clearance of psoriasis in patients treated with photochemotherapy. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:752–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.6.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harth W, Gieler U, Kusnir D, Tausk FA. Clinical Management in Psychodermatology. Berlin HeidlebergSpringer Publications; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Quinn LM, Mostow EN, Zyzanski SJ. Skindex, a quality-of-life measure for patients with skin disease: Reliability, validity, and responsiveness. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107:707–13. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12365600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerdes S, Mrowietz U. Comorbidities and psoriasis. Impact on clinical practice. Hautarzt. 2012;63:202–13. doi: 10.1007/s00105-011-2230-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimball AB, Wu EQ, Guérin A, Yu AP, Tsaneva M, Gupta SR, et al. Risks of developing psychiatric disorders in pediatric patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:651–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.11.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Araya R, Wynn R, Lewis G. Comparison of two self administered psychiatric questionnaires (GHQ-12 and SRQ-20) in primary care in Chile. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1992;27:168–73. doi: 10.1007/BF00789001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chowdhury AN, Bramha A, Sanyal D. The validation of the Bengali version of self reporting questionnaire (SRQ) Indian J Clin Psychol. 2003;30:56–61. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mattoo SK, Handa S, Kaur I, Gupta N, Malhotra R. Psychiatric morbidity in psoriasis: Prevalence and correlates in India. Ger J Psychiatry. 2005;8:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akay A, Pekcanlar A, Bozdag KE, Altintas L, Karaman A. Assessment of depression in subjects with psoriasis vulgaris and lichen planus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:347–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bharath S, Shamasundar C, Raghuram R, Subbakrishna DK. Psychiatric morbidity in leprosy and psoriasis - A comparative study. Indian J Lepr. 1997;69:341–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esposito M, Saraceno R, Giunta A, Maccarone M, Chimenti S. An Italian study on psoriasis and depression. Dermatology. 2006;212:123–7. doi: 10.1159/000090652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sampogna F, Sera F, Abeni D. IDI Multipurpose Psoriasis Research on Vital Experiences (IMPROVE) Investigators. Measures of clinical severity, quality of life, and psychological distress in patients with psoriasis: A cluster analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:602–7. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202X.2003.09101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar S, Kachhawha D, Das Koolwal G, Gehlot S, Awasthi A. Psychiatric morbidity in psoriasis patients: A pilot study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:625. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.84074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han C, Lofland JH, Zhao N, Schenkel B. Increased prevalence of psychiatric disorders and health care-associated costs among patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:843–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar V, Mattoo SK, Handa S. Psychiatric morbidity in pemphigus and psoriasis: A comparative study from India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013;6:151–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]