Abstract

Background & aims

Diets with low omega (ω)-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) to eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) plus docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) ratios have been shown to decrease aortic cholesterol accumulation and have been suggested to promote weight loss. The involvement of the liver and gonadal adipose tissue (GAT) in mediating these effects is not well understood. LDL receptor null mice were used to assess the effect of an atherogenic diet with different ω-6:EPA+DHA ratios on weight gain, hepatic and GAT lipid accumulation, and their relationship to atherosclerosis.

Methods

Four groups of mice were fed a high saturated fat and cholesterol diet (HSF ω-6) alone, or with ω-6 PUFA to EPA+DHA ratios up to 1:1 for 32 weeks. Liver and GAT were collected for lipid and gene expression analysis.

Results

The fatty acid profile of liver and GAT reflected the diets. All diets resulted in similar weight gains. Compared to HSF ω-6 diet, the 1:1 ratio diet resulted in lower hepatic total cholesterol (TC) content. Aortic TC was positively correlated with hepatic and GAT TC and triglyceride. These differences were accompanied by significantly lower expression of CD36, ATP-transporter cassette A1, scavenger receptor B class 1, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR), acetyl-CoA carboxylase alpha, acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 5, and stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase 1 (SCD1) in GAT, and HMGCR, SCD1 and cytochrome P450 7A1 in liver.

Conclusions

Dietary ω-6:EPA+DHA ratios did not affect body weight, but lower ω-6:EPA+DHA ratio diets decreased liver lipid accumulation, which possibly contributed to the lower aortic cholesterol accumulation.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Liver, Gonadal adipose tissue, Fatty acids, Lipid metabolism, Omega-3 fatty acids

1. Introduction

Very long-chain omega (ω)-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) have a multifactorial role in cardiovascular disease risk reduction.1 Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, C20:5 ω-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, C22:6 ω-3) are the major dietary very long chain ω-3 PUFA, which can reduce circulating triglyceride concentrations, which is an independent risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.2 Western-type diet induced steatosis and expanded visceral adipose tissue may contribute to atherosclerotic lesion development.3 EPA and DHA can reduce cholesterol accumulation in the aortic wall as well as lipid content in the liver and visceral adipose tissue,4,5 which may be related to its anti-atherosclerotic properties.

Liver is an essential organ for very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) formation, and visceral adipose tissue is the major organ for triglyceride storage in humans. Gonadal adipose tissue (GAT) is the major visceral adipose tissue depot in mice. This adipose tissue consists of ~50% adipocytes and ~50% stromal vascular cells, the latter being made up of endothelial progenitor cells, preadipocytes, mesenchymal stem cells, T regulatory cells and macrophages.6 Western-type diets increase adipose tissue mass, which is characterized by increased adipocyte triglyceride accumulation and immune cells recruitment. Enlarged adipocytes release free fatty acids into the bloodstream. Free fatty acids released from GAT are taken up by liver and other tissues for oxidation or the synthesis of complex lipids, primarily triglyceride and phospholipids. Triglyceride is either stored in hepatocytes or assembled into VLDL and secreted into the bloodstream. If hepatic triglyceride synthesis exceeds its oxidation and secretion, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) develops.7

The hepatic production of VLDL is highly dependent on the hepatic triglyceride and cholesterol pool.8 High levels of hepatic VLDL production lead to an increase in plasma LDL concentrations and promote cholesteryl ester (CE) accumulation in the arterial wall.9 Our previous work in the LDL receptor null (LDLr−/−) mice demonstrated that an atherogenic diet with a 1:1 ratio of ω-6 PUFA to EPA plus DHA resulted in lower serum non-high density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol (non-HDL-C) concentrations, lower elicited peritoneal macrophage CE accumulation and less aortic lesion formation compared to the atherogenic diet with ω-6 alone.5 Un-determined was the potential relationship between the arterial wall cholesterol accumulation and lipid accumulation in the liver and GAT. We hypothesize that the atherogenic diet with lower ratios of ω-6 PUFA to EPA plus DHA would result in lower lipid content in the liver and GAT, which may in turn influence aortic lesion formation in male LDLr−/− mice. In light of the reports that increased consumption of very long chain ω-3 fatty acids is associated with lower body weights in animal models,10 a secondary aim was to assess the effect of the dietary interventions on body weight gain.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and diets

Forty 8-week old, male LDLr−/− mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) initially weighing 20.2 ± 2.6 g were placed in individual cages with stainless-steel wire bottoms in a windowless room maintained at 22–24 °C, 45% relative humidity and a daily 10/14 light/dark cycle with the light period from 06:00 to 16:00. After 1-week of acclimation, mice were weighed and randomly assigned to one of four groups. Four groups of mice (n = 10/group) were fed either a high saturated fat and cholesterol (HSF) diet without EPA and DHA (HSF ω-6), or with ω-6:EPA+DHA at ratios of 20:1 (HSF R = 20:1), 4:1 (HSF R = 4:1), and 1:1 (HSF R = 1:1) for 32 weeks as described previously.5 Food intake and body weights were monitored weekly. Water and diets were provided ad libitum. The HSF ω-6 diet has previously been shown to induce atherosclerotic lesion formation in the LDLr−/− mouse.11 The ratio of ω-6:EPA+DHA in the diets was manipulated by adding different amounts of fish oil (Omega Protein Inc., Houston, TX) and safflower oil. The fatty acid composition of the diets was confirmed using gas chromatography (GC).5 At week 32, after a 16–18 h fast, the mice were anesthetized with CO2 and sacrificed by exsanguinations. Serum was separated from blood by centrifugation at 1100 × g at 4 °C for 25 min. The protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging, Tufts University, and was in accordance with guidelines provided by the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. A portion of this work, addressing a different experimental question, has been reported previously.5

2.2. Serum lipid profile and atherosclerotic lesion quantitation

Serum triglyceride, TC and HDL-C concentrations were measured using an Olympus AU400 analyzer with enzymatic reagents (Olympus America, Melville, NY) as previously described.5 Non-HDL-C was calculated as the difference between TC and HDLC. Aortic TC was quantified as previously described.5 A portion of these data, addressing a different experimental question, have been published.5

2.3. Fatty acid profile and lipid content in liver and GAT

Lipids were extracted overnight using chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v).12 A portion of the extract was used to determine fatty acid profiles using GC technology as previously described13 and a portion was used to measure TC, free cholesterol (FC) and triglyceride concentrations using Wako assay kits (Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA). The delipidated tissue pellet was digested in 1 N NaOH, and total protein was measured using a BCA kit (Pierce Ins., Rockford, IL).

2.4. RNA extraction and real-time PCR

RNA was extracted from hepatic and GAT using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNA was synthesized from RNA using SuperScript™ Π reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Primers for acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 5 (ACSL5), stearoyl-Coenzyme A desaturase 1 (SCD1), cytochrome P450, family 7, subfamily a, polypeptide 1 (CYP7α1), fatty acid binding protein 5 (FABP5), SRA1, sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1 (SREBF1), fatty acid synthase (FASN), 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-Coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR), acetyl-Coenzyme A carboxylase alpha (ACACA), scavenger receptor A1 (SRA1), scavenger receptor B1 (SR-B1), ATP-transporter cassette A1 (ABCA1), CD36, and β-actin (Table 1) were designed using Primer Express version 2.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). β-Actin was used as an endogenous control. Primer amplification efficiency and specificity were verified for each set of primers. cDNA levels of the genes of interest were measured using power SYBR green master mix on real-time PCR 7300 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as previously described.5 mRNA fold change was calculated using the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method.14

Table 1.

Mouse oligonucleotide sequences of primers.

| Gene name | Accession no. | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|---|

| SRA1 | AF203781 | TCTACAGCAAAGCAACAGGAGG | TCCACGTGCGCTTGTTCTT |

| SR-B1 | NM_016741 | TGGAACGGACTCAGCAAGATC | AATTCCAGCGAGGATTCGG |

| CD36 | NM_007643 | ATTAATGGCACAGACGCAGC | CCGAACACAGCGTAGATAGACC |

| ABCA1 | NM_013454 | CCTGCTAAAATACCGGCAAGG | GTAACCCGTTCCCAACTGGTTT |

| ACACA | NM_133360 | TGGTTTGGCCTTTCACATGAG | GCTGGAGAAGCCACAGTGAAAT |

| HMGCR | NM_008255 | CATCATCCTGACGATAACGCG | AGGCCAGCAATACCCAGAATG |

| FASN | NM_007988 | AGTTGCCCGAGTCAGAGAACCT | CATAGAGCCCAGCCTTCCATCT |

| SREBF1 | NM_011480 | TTGAGGATAGCCAGGTCAAAGC | GGATTGCAGGTCAGACACAGAA |

| ACSL5 | NM_027976 | AAGACGATCATCCTCATGGACC | CCTATATTCTCCGCATCATGCA |

| SCD1 | NM_009127 | AAGCTCTACACCTGCCTCTTCG | GCCTTGTAAGTTCTGTGGCTCC |

| CYP7α1 | NM_007824 | CGAAGGCATTTGGACACAGA | TCCGTGGTATTTCCATCACTTG |

| FABP5 | NM_010634 | AACTGAGACGGTCTGCACCTTC | CACTCCACGATCATCTTCCCAT |

| β-Actin | NM_007393 | CTTTTCCAGCCTTCCTTCTTGG | CAGCACTGTGTTGGCATAGAGG |

ACSL5, acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 5; SCD1, stearoyl-Coenzyme A desaturase 1; CYP7a1, cytochrome P450, family 7, subfamily a, polypeptide 1; FABP5, fatty acid binding protein 5; SRA1, scavenger receptor type A1; SREBF1, sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor; FASN, fatty acid synthase; HMGCR, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-Coenzyme A reductase; ACACA, acetyl-Coenzyme A carboxylase alpha; SR-B1, scavenger receptor class B, member 1; ABCA1, ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A, member 1.

2.5. Statistical analysis

SPSS software (version 18.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for all statistical analyses. Bivariate relationships were determined using Pearson’s correlations. One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was performed for multiple comparisons. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. Data are presented in text, figures, and tables as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

3. Results

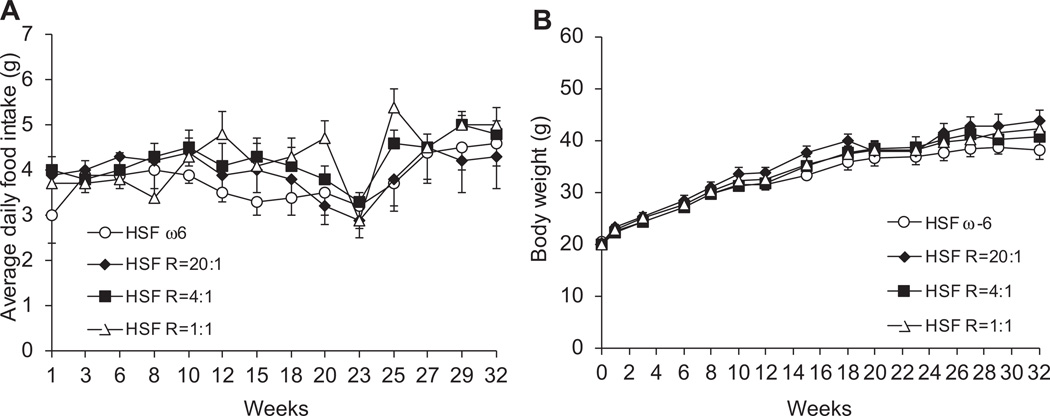

3.1. Body weight and food intake remained similar

No significant differences were observed in food intake or body weight among four groups of mice throughout the 32-week feeding period (Fig. 1). These data suggest that lower ω-6:EPA+DHA ratio diets did not alter the rate of weight gain.

Fig. 1.

Average daily food intake (A) and body weight (B). Data are presented as means ± SEM. One way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was performed for multiple comparisons. There was no difference in food intake and body weight throughout the feeding period.

3.2. Fatty acid profile in liver and GAT reflected that of diets

The hepatic profile of total SFA, MUFA, and PUFA was similar among four groups (Supplementary table 1). The profile of total MUFA was similar in GAT among four groups (Supplementary table 2). With the decreasing ratios of ω-6:EPA+DHA in the diets the mol% of ω-6 PUFA was decreased, while the mol% of ω-3 PUFA was increased. These changes resulted in a progressive decrease in the ω-6:EPA+DHA ratio in both liver and GAT.

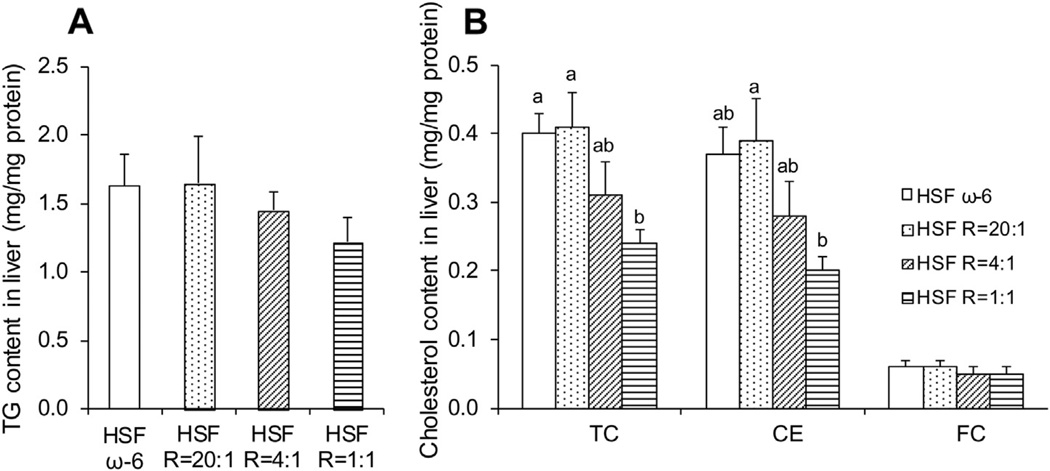

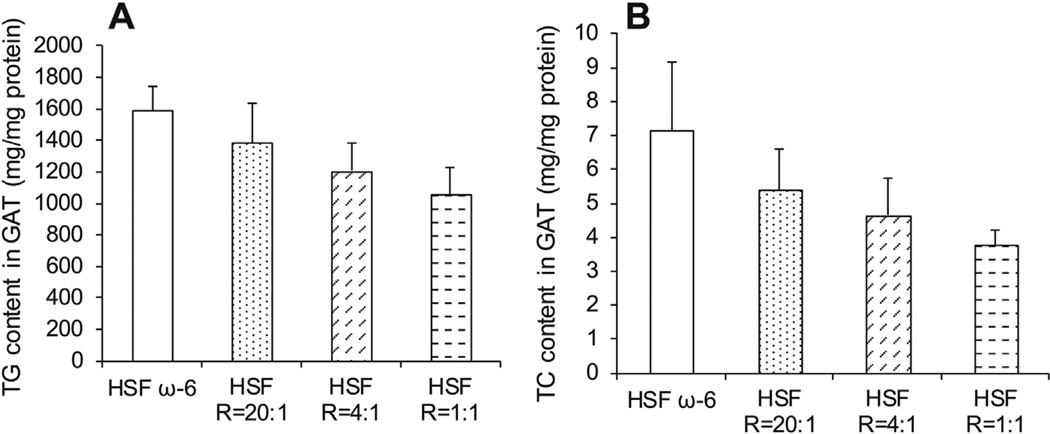

3.3. Lower ω-6:EPA+DHA ratio diets resulted in lower cholesterol content in liver

The HSF R = 1:1 compared to HSF ω-6 diet significantly lowered hepatic TC and CE content (mg/mg protein) (Fig. 2). As ratios of ω- 6:EPA+DHA in the diet decreased, the hepatic triglyceride content and GAT cholesterol and triglyceride content were progressively lowered, but the differences did not attain statistical significance (Figs. 2 and 3). These findings are consistent with the prior observation in these animals that as ratios of ω-6:EPA+DHA in the diet decreased, the TC content of the aortas declined.5

Fig. 2.

Hepatic triglyceride (TG) (A) and cholesterol (B) content. Data are presented as means ± SEM. One way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was performed for multiple comparisons. Bars without a common superscript differ, p < 0.05.

Fig. 3.

GAT triglyceride (TG) (A) and TC (B) content. Data are presented as means ± SEM. One way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was performed for multiple comparisons.

3.4. Aortic TC content positively correlated with lipid concentrations in blood, liver and GAT

Aortic TC content was positively correlated with serum TC and non-HDL-C concentrations, and hepatic TC, hepatic triglyceride, GAT TC, and GAT triglyceride content (all at p < 0.05) (Table 2). These data suggest that lower lipid accumulation in the liver and GAT resulting from the lower ω-6:EPA+DHA ratio diets may have contributed to less aortic lesion formation.

Table 2.

Correlation between aortic TC content and lipid content in serum, liver and GAT.

| Aortic TC content (ug/mg of protein) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson correlation |

p-Value (2-tailed) |

||

| Serum lipid | TC | 0.410 | 0.020 |

| concentrations (mg/dL) | Non-HDL-C | 0.419 | 0.017 |

| Liver lipid content | TC | 0.610 | 0.000 |

| (mg/mg protein) | TG | 0.484 | 0.007 |

| GAT lipid content | TC | 0.509 | 0.009 |

| (mg/mg protein) | TG | 0.668 | 0.000 |

Bivariate relationships were determined using the Pearson’s correlations. TC, total cholesterol; Non-HDL-C, non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; GAT, gonadal adipose tissue.

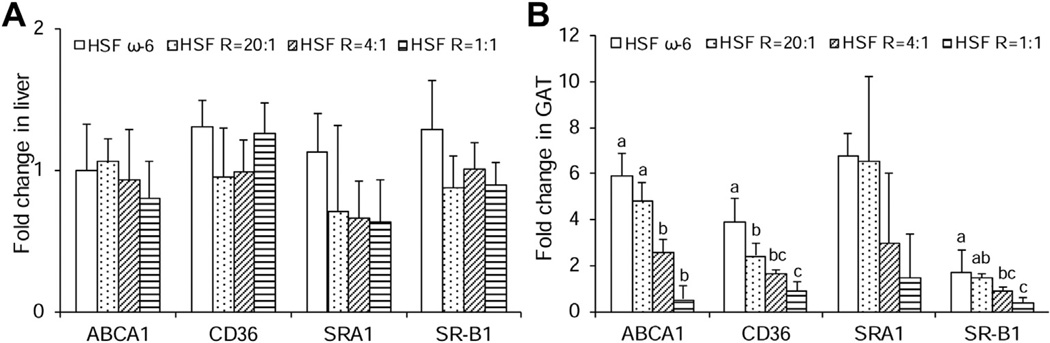

3.5. HSF R = 1:1 diet resulted in lowered gene expression of scavenger receptors in GAT

There were no significant differences in hepatic gene expression of ABCA1, SRA1, SR-B1, and CD36 among the four diet groups (Fig. 4A). However, diets with lower ratios of ω-6:EPA+DHA progressively decreased the expression of all scavenger receptors in GAT (Fig. 4B). As compared to the HSF ω-6 diet, the HSF R = 1:1 diet lowered the gene expression of ABCA1, SR-B1, CD36 and SRA1 by 11.3, 4.3, 4.5 and 4.6-fold, respectively, although the difference for SRA1 did not reach the significance. These data suggest that lower ω-6:EPA+DHA ratio diets significantly reduces the gene expression of scavenger receptors in GAT, which may, at least in part, contribute to the tissue lipid composition changes, and have little effect in liver.

Fig. 4.

mRNA levels of scavenger receptors in liver (A) and GAT (B) isolated from LDLr−/− mice at the end of the 32-week feeding period. Data are presented as means ± SEM. One way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was performed for multiple comparisons. Bars without a common superscript differ, p < 0.05.

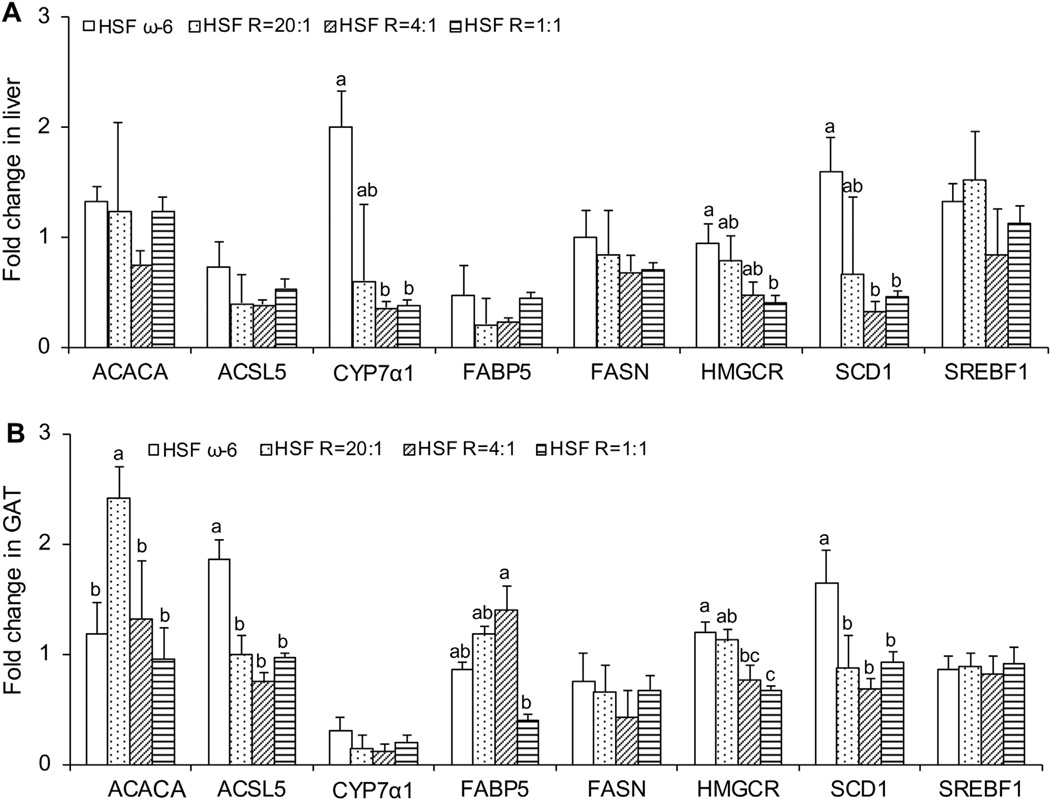

3.6. HSF R = 1:1 diet lowered expression of lipid metabolism genes in liver and GAT

Compared to the HSF ω-6 diet, the HSF R = 1:1 diet resulted in significantly lowered gene expression of CYP7α1, SCD1, and HMGCR in the liver (Fig. 5A). In GAT, this diet resulted in significantly lowered gene expression of ACSL5, HMGCR and SCD1 (Fig. 5B). The effect of the lower ω-6:EPA+DHA ratio diets on the expression of lipogenic genes in the liver and GAT is consistent with the composition effects observed.

Fig. 5.

mRNA levels of lipid metabolism genes in liver (A) and GAT (B) isolated from LDLr−/− mice at the end of the 32-week feeding period. Data are presented as means ± SEM. One way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was performed for multiple comparisons. Bars without a common superscript differ, p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

We have previously reported that feeding diets high in saturated fat and cholesterol supplemented with very long chain ω-3 fatty acids, having lower ratios of ω-6:EPA+DHA, to LDLr−/− mice resulted in a less atherogenic serum lipid profile, macrophage deposition in the aortic wall and atherosclerotic lesion development compared to the mice fed unsupplemented diets.5 Addressed in this report is the potential relationship between the atherosclerotic lesion development and liver and GAT lipid metabolism. We found that the atherogenic diet with lower ratios of ω- 6:EPA+DHA resulted in less lipid accumulation in the liver and a trend toward lower lipid levels in GAT, similar to that observed in the aorta. Consistent with these data, mice fed diets with the lowest ω-6:EPA+DHA ratio also had lower expression of ACACA, ACSL5, FABP5, HMGCR, SCD1, and scavenger receptors.

The experimental diets were designed to have equivalent compositions with respect to total fat, and the proportions of SFA, MUFA, and PUFA. The variable component was the ratio of ω-6 PUFA to EPA+DHA. The amount of EPA+DHA in the HSF R = 20:1, HSF R = 4:1 and HSF R = 1:1 diets provided 0.1%, 0.5% and 1% energy, respectively. Current recommendations for individuals with hypertriglyceridemia are to consume 2–4 g of EPA+DHA per day.15 For a person consuming 2200 kcal, they are equivalent to approximately 0.8–1.6% energy from EPA and DHA, consistent with the diet having the lowest ω-6: EPA+DHA ratio used in the current study.

A growing body of evidence suggests elevated hepatic triglyceride content, resembling NAFLD in humans, is associated with increased the risk of developing atherosclerosis.16 From the clinical perspective, using nutrients to decrease hepatic lipid content can partially inhibit atherosclerotic lesion development. Our findings are consistent with prior data from human and animal studies to suggest that fish oil supplement can minimize the development of NAFLD and liver fat accumulation,17 which correlate with lower aortic cholesterol accumulation.

Increased triglyceride accumulation in visceral adipose tissue may promote atherogenesis by triggering a systemic inflammatory response. Enlarged adipocytes increase blood free fatty acid concentrations which are available for uptake by other tissues, including the liver, resulting in increased VLDL production and promoting atherogenesis.18 Fish oil supplements have been reported to decrease fat accumulation, particularly visceral fat, in a number of animal models but not weight gain.4 This observation was confirmed in the current study as we found no evidence that relatively high intakes of EPA and DHA altered body weight gain.

In order to understand the mechanism that may be responsible for the relationship between atherosclerotic lesion development and lipid metabolism in liver and GAT, we assessed mRNA expression of scavenger receptors and critical genes involved in lipid metabolism. We demonstrated, for the first time to our knowledge, that the atherogenic diet with lower ratios of ω-6:EPA+DHA decreased the expression of CD36 in GAT. CD36 is highly expressed in adipose tissues, myocardial and skeletal muscle, and macrophages, and it facilitates modified LDL and fatty acid uptake by those tissues.19 CD36 has different functions in different types of cells. Macrophages treated with EPA or DHA have been reported to decrease CD36 expression and also the uptake of modified LDL,19 which would impede foam cell formation. CD36 can also induce adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis.20 Given all this, the finding that CD36 expression in GAT is reduced by lowering ω-6:EPA+DHA ratio may provide useful information to help understand the mechanism mediating the effect of EPA+DHA on atherosclerotic lesion formation.

Two important membrane proteins involved in cholesterol efflux in adipocytes are ABCA1 and SR-B1.21 SR-B1 mediates the selective efflux of cellular cholesterol to HDL. ABCA1 promotes free cholesterol and phospholipid efflux from cells to HDL. Most of the body’s cholesterol is stored in adipose tissues. ABCA1 and SR-B1 play an important role in cholesterol homeostasis in adipose tissues and HDL biogenesis and modulation.21,22 We demonstrate that the atherogenic diet with lower ratios of ω-6:EPA+DHA decreased the expression of ABCA1 and SR-B1 in GAT, which might partially contribute to the slightly lower serum HDL-C concentrations reported in our previous publication.5

HMGCR and CYP7α1 are key enzymes involved in cholesterol and bile acid synthesis, respectively. Consistent with other studies,23,24 the diets with lower ratios of ω-6:EPA+DHA significantly decreased the hepatic HMGCR expression in liver. To date, few studies have investigated the effect of very long chain ω-3 PUFA on HMGCR expression in adipose tissue. The current study demonstrated that as compared to the HSF ω-6, diets with lower ω- 6:EPA+DHA ratios significantly downregulated the expression of HMGCR in GAT, which was associated with the lower TC content. Increased use of cholesterol for bile acid synthesis has been shown to lower atherosclerotic lesion formation. CYP7α1 is a key enzyme for bile acid synthesis. The most important regulator for CYP7α1 expression is cellular cholesterol levels. Increased cellular cholesterol accumulation can result in the higher expression of CYP7α1.25 In the current study, as the dietary ratios of ω-6:EPA+DHA decreased, hepatic cholesterol content was gradually lowered, which may partially contribute to the lower expression of CYP7α1 in liver.

FABP5, ACACA, ASCL5 and SCD1 are important lipogenic genes. Both FABP4 and FABP5 are primarily expressed in adipocytes and/or macrophages.26 Decreased expression of those FABP4 and FABP5 in adipose tissue has been correlated to less lipid accumulation, reduced inflammatory response, and enhanced insulin sensitivity.27 In our current study, the triglyceride content of GAT was inversely associated with FABP5 expression. This might be a compensatory mechanism to prevent lipid accumulation in GAT. ACACA is a key enzyme that uses acetyl-CoA to synthesize malonyl-CoA, a building block for fatty acid synthesis and an inhibitor for fatty acid oxidation.28 Fish oil has been shown to decrease the expression of ACACA in hepatic and adipose tissue in research animals.29 ACSL5 can convert long chain fatty acids to fatty acyl-CoA. To date, few studies have investigated the role of very long chain ω-3 PUFA in the expression of ACSL5 in hepatic and adipose tissues. Our data demonstrate that dietary EPA and DHA significantly decrease the expression of ASCL5 in GAT. SCD1 is one of four isomers in SCD family, which can convert palmitate and stearate into the palmitoleate and oleate, respectively.30 Saturated fatty acids and deficiency of ω-3 fatty acids increase SCD1 expression in liver and other tissues.30 In the current study, as compared to the HSF ω- 6 diet, lower ratio diets significantly reduced the SCD1 expression in liver and GAT. Taken together, diets with lower ω-6:EPA+DHA ratios decreased lipogenic gene expression, which may partially contribute to the lower lipid accumulation in the liver and GAT.

Clinical practice shows that liver and visceral adipose tissue may play an important role in modulating atherosclerotic lesion development. Our current report is of particular interest in clinical nutrition as it demonstrates that with the background of an atherogenic diet, the lower ω-6:EPA+DHA ratio diets decreased lipid accumulation in liver and GAT, which may partially contribute to the anti-atherosclerotic response. The lower ω-6:EPA+DHA ratio diets did not have any impact on body weight.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Amy Wu for helping the lipid extraction from liver and GAT, Ming Sun and Jia Zhang for helping with the data organization and part of the statistical analysis.

Funding sources

The study was supported by the Texas Tech Startup Funding to Shu Wang and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grant T32 HL69772-01A1 (Shu Wang).

Abbreviations

- GAT

gonadal adipose tissue

- HSF

high saturated fat and cholesterol

- R

ratio of ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids to eicosapentaenoic acid plus docosahexaenoic acid.

Footnotes

Statement of authorship

S.W., D.W., and A.H.L. planned study. S.W., N.R.M., X.Y., and D.W. performed the analytical work. D.R., P.G., and C.L.S. provided scientific expertise. S.W. and P.B. performed data analysis. S.W. and A.H.L. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflict of interest in relation to this study.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2013.04.009.

References

- 1.De Caterina R. n-3 fatty acids in cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jun 23;364(25):2439–2450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1008153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wierzbicki AS, Clarke RE, Viljoen A, Mikhailidis DP. Triglycerides: a case for treatment? Curr Opin Cardiol. 2012 Jul;27(4):398–404. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e328353adc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatia LS, Curzen NP, Calder PC, Byrne CD. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a new and important cardiovascular risk factor? Eur Heart J. 2012 May;33(10):1190–1200. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buckley JD, Howe PR. Long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids may be beneficial for reducing obesity-a review. Nutrients. 2010 Dec;2(12):1212–1230. doi: 10.3390/nu2121212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang S, Wu D, Matthan NR, Lamon-Fava S, Lecker JL, Lichtenstein AH. Reduction in dietary omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids: eicosapentaenoic acid plus docosahexaenoic acid ratio minimizes atherosclerotic lesion formation and inflammatory response in the LDL receptor null mouse. Atherosclerosis. 2009 May;204(1):147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Z, Nakayama T. Inflammation, a link between obesity and cardiovascular disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:535918. doi: 10.1155/2010/535918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wierzbicki AS, Oben J. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and lipids. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2012 Aug;23(4):345–352. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283541cfc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adiels M, Olofsson SO, Taskinen MR, Boren J. Overproduction of very low-density lipoproteins is the hallmark of the dyslipidemia in the metabolic syndrome. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008 Jul;28(7):1225–1236. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.160192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonora E, Targher G. Increased risk of cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease in NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 Jul;9(7):372–381. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hao Q, Lillefosse HH, Fjaere E, Myrmel LS, Midtbo LK, Jarlsby RH, et al. High-glycemic index carbohydrates abrogate the antiobesity effect of fish oil in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012 May 15;302(9):E1097–E1112. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00524.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Napoli C, Williams-Ignarro S, De Nigris F, Lerman LO, Rossi L, Guarino C, et al. Long-term combined beneficial effects of physical training and metabolic treatment on atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Jun 8;101(23):8797–8802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402734101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957 May;226(1):497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lichtenstein AH, Matthan NR, Jalbert SM, Resteghini NA, Schaefer EJ, Ausman LM. Novel soybean oils with different fatty acid profiles alter cardiovascular disease risk factors in moderately hyperlipidemic subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006 Sep;84(3):497–504. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001 Dec;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kris-Etherton PM, Hill AM. N-3 fatty acids: food or supplements? J Am Diet Assoc. 2008 Jul;108(7):1125–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pacana T, Fuchs M. The cardiovascular link to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a critical analysis. Clin Liver Dis. 2012 Aug;16(3):599–613. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parker HM, Johnson NA, Burdon CA, Cohn JS, O’Connor HT, George J. Omega-3 supplementation and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2012 Apr;56(4):944–951. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meshkani R, Adeli K. Hepatic insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Clin Biochem. 2009 Sep;42(13, 14):1331–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLaren JE, Michael DR, Guschina IA, Harwood JL, Ramji DP. Eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid regulate modified LDL uptake and macropinocytosis in human macrophages. Lipids. 2011 Nov;46(11):1053–1061. doi: 10.1007/s11745-011-3598-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christiaens V, Van Hul M, Lijnen HR, Scroyen I. CD36 promotes adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012 Jul;1820(7):949–956. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baranova I, Vishnyakova T, Bocharov A, Chen Z, Remaley AT, Stonik J, et al. Lipopolysaccharide down regulates both scavenger receptor B1 and ATP binding cassette transporter A1 in RAW cells. Infect Immun. 2002 Jun;70(6):2995–3003. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.6.2995-3003.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, McGillicuddy FC, Hinkle CC, O’Neill S, Glick JM, Rothblat GH, et al. Adipocyte modulation of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Circulation. 2010 Mar 23;121(11):1347–1355. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.897330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du C, Sato A, Watanabe S, Wu CZ, Ikemoto A, Ando K, et al. Cholesterol synthesis in mice is suppressed but lipofuscin formation is not affected by long-term feeding of n-3 fatty acid-enriched oils compared with lard and n-6 fatty acid-enriched oils. Biol Pharm Bull. 2003 Jun;26(6):766–770. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arai T, Kim HJ, Chiba H, Matsumoto A. Anti-obesity effect of fish oil and fish oil-fenofibrate combination in female KK mice. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2009 Oct;16(5):674–683. doi: 10.5551/jat.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luoma PV. Cytochrome P450 and gene activation—from pharmacology to cholesterol elimination and regression of atherosclerosis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008 Sep;64(9):841–850. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0515-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lan H, Cheng CC, Kowalski TJ, Pang L, Shan L, Chuang CC, et al. Small-molecule inhibitors of FABP4/5 ameliorate dyslipidemia but not insulin resistance in mice with diet-induced obesity. J Lipid Res. 2011 Apr;52(4):646–656. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M012757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furuhashi M, Fucho R, Gorgun CZ, Tuncman G, Cao H, Hotamisligil GS. Adipocyte/macrophage fatty acid-binding proteins contribute to metabolic deterioration through actions in both macrophages and adipocytes in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008 Jul;118(7):2640–2650. doi: 10.1172/JCI34750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wakil SJ, Abu-Elheiga LA. Fatty acid metabolism: target for metabolic syndrome. J Lipid Res. 2009 Apr;50(Suppl.):S138–S143. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800079-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hiller B, Herdmann A, Nuernberg K. Dietary n-3 fatty acids significantly suppress lipogenesis in bovine muscle and adipose tissue: a functional genomics approach. Lipids. 2011 Jul;46(7):557–567. doi: 10.1007/s11745-011-3571-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sampath H, Ntambi JM. The role of stearoyl-CoA desaturase in obesity, insulin resistance, and inflammation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011 Dec;1243:47–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.