Abstract

Introduction: Nowadays, finding new therapeutic compounds from natural products for treatment and prevention of a variety of diseases including cardiovascular disorders is getting a great deal of attention. This approach would result in finding new drugs which are more effective and have fewer side effects than the conventional medicines. The present study was designed to investigate the anti-inflammatory effect of the methanolic extract of Marrubiumvulgare, a popular traditional medicinal herb, on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction (MI) in rat model.

Methods: Male Wistar rats were assigned to 6 groups of control, sham, isoproterenol, and treatment with 10, 20, and 40 mg/kg/12h of the extract given orally concurrent with MI induction. A subcutaneous injection of isoproterenol (100 mg/kg/day) for two consecutive days was used to induce MI. Then, histopathological changes and inflammatory markers were evaluated.

Results: Isoproterenol injection increased inflammatory response, as shown by a significant increase in peripheral neutrophil count, myocardial myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity and serum levels of creatinine kinase-MB (CK-MB) and TNF-α (p<0.001). In the groups treated with 10, 20 and 40 mg/kg of M.vulgare extract serum CK-MB was subsided by 55.4%, 52.2% and 69%, respectively. Also treatment with the extract (40 mg/kg) significantly reduced (p<0.001) MPO activity in MI group. The levels of TNF-α was also considerably declined in the serums of MI group (p<0.001). In addition, peripheral neutrophil count, was significantly lowered by all doses of the extract (p<0.001). Interstitial fibrosis significantly was attenuated in treated groups compared with control MI group.

Conclusion: The results of study demonstrate that the M. vulgare extract has strong protective effects against isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction and it seems possible that this protection is due to its anti-inflammatory effects.

Keywords: Marrubium vulgare, Myocardial infarction Isoproterenol, Anti-inflammatory, Myeloperoxidase, TNF-α

Introduction

Myocardial infarction is an acute condition of necrosis of the myocardium that occurs because of imbalance between coronary blood supply and myocardial demand.1 Myocardial infarction (MI) is associated with inflammatory response and considered part of a spectrum referred to as acute coronary syndrome.2 Acute MI is an important ischemic heart disease and a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.2 Myocardial infarction may lead to impairment of systolic or diastolic function and to increased predisposition to arrhythmias and other long-term complications.3 Thus, it needs to be prevented or treated immediately after occurrence. Polymorph nuclear leukocytes (PMNs) especially neutrophils, are associated with the acute inflammatory response to tissue injury and have the capacity to produce oxygen-derived free radicals.4 The destructive effect of free radicals has been postulated.5 In addition, Epidemiological studies have shown that the total white blood cell count is an independent risk factor for ischemic heart disease.6

The complexity, chemical diversity, and biological properties of natural products have played an important role in the discovery and development of new compounds.7 Since ancient times, natural products have been used for the relief and cure of diseases by humans. This caused new efficient therapies on plants scientific research.8 In recent years, natural products are of great interest to be used as a novel cure to treat cardiovascular diseases.9 Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of natural products are supposed to be effective in treating cardiovascular diseases.9

Marrubium vulgare, from family Lamiaceae, is a popular traditionally used herb in many countries as an antidiabetic and antihypertensive agent.10,11 M. vulgare is known for its remarkable diterpene content. Marrubiin and marrubenol are two important diterpenes from M. vulgare, which have shown variety of activities. Marrubiin is reported to own analgesic, antidiabetic, antiplatelet, anticoagulant, antispasmodic, anti-hypertensive, and antiedematogenic properties.12-15 Marrubenol has shown a relaxant activity on rat-isolated aorta through blocking the L-type calcium channels.16

Methanolic extract of M. vulgare has shown remarkable in vitro antioxidant activity and anti-free-radical property because of presence of flavonoids, diterpenes, and phenols.17

Anti-inflammatory property of M. vulgare is demonstrated by studies with aerial parts. The compounds including (+) (E)-caffeoyl-l-malic acid, acteoside, forsythoside B, arenarioside, and ballotetroside are identified as the principally bioactive constituents related to the anti-inflammatory activity. In addition, glycosidic phenylpropanoid esters from the aerial parts were shown to inhibit the cyclooxigenase enzyme (COX) and three of them, acteoside, forsythoside B and arenarioside, displayed higher inhibitory potencies on Cox-2 than on Cox-1.18

The rat model of isoproterenol-induced MI offers a standardized non-invasive technique for studying the effects of various potential cardioprotective therapies.1,19 Isoproterenol is a synthetic non-selective β-adrenoceptor agonist that its subcutaneous injection induces heart failure and suppressed cardiac functions because of myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis. Also due to the myocardial injury after isoproterenol injection the inflammatory response increases.1,19

So far, however, there has been no discussion about the possible positive effects of M. vulgare on cardiac injuries like MI. Basically, this is the first study investigating the protective role of M. vulgare on the cardiac injury by evaluating inflammatory markers in the rat model. The purpose of this paper is to find out cardioprotective effect of M. vulgare methanolic extract on isoproterenol-induced MI in rat model. Anti-inflammatory properties such as neutrophil infiltration into blood and heart tissue, inflammatory markers and histopathological changes were examined and their modulation with different doses of M. vulgare extract was evaluated. Result of this study may introduce a new efficient herbal cure in prevention and improvement of acute myocardial infarction.

Materials and methods

Plant material

The aerial parts of Marrubium vulgare were collected in 2012 during flowering stage on June from Kiasar in Mazandaran province, Iran. The botanical identification was made by Dr. M. Mazandarani (Department of Biology, Azad Islamic University, Gorgan, Iran). Voucher specimens were deposited at the herbarium of the Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Extract preparation and TLC analysis

Dried aerial parts (200g) were grounded and extracted with methanol (2L×4) by maceration at room temperature and the solvent was removed at 400C using a rotary evaporator. A greenish residue weighing 17.8 % (w/w) was obtained and kept in air tight bottle in a refrigerator until use. To identify the chemical constituents, the obtained methanolic extract was subjected to preliminary phytochemical screening. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on silica gel GF254 with benzene-acetone (17:3). Detecting the spots with spraying H2SO4 10% in EtOH revealed the presence of Marrubiin at Rf=0.63 as a major compound in the extract.20

Animals

Male albino wistar rats (260-280g) were used in this study. Rats were housed at constant temperature (20±1.8˚C) and relative humidity (50±10%) in standard polypropylene cages, six per cage, under a 12 h light/dark cycle, and were allowed food and water freely. This study was performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz-Iran (National Institutes of Health publication No 85-23, revised 1985).

Induction of acute myocardial infarction

Isoproterenol (Sigma, USA) was dissolved in normal saline and injected subcutaneously to rats (100 mg/kg) for two consecutive days at an interval of 24 h to induce acute myocardial infarction. Animals were sacrificed 48 h after the first dose of isoproterenol.

Experimental protocol

The animals were randomly assigned into 6 groups, each consisted of 6 rats. Rats in group 1 (normal control) received a subcutaneous injection of normal saline (0.5 ml) and were left untreated for the whole period of the experiment. In group 2 (sham), rats received a subcutaneous injection of normal saline and M.vulgare extract was given orally (40mg/kg) 30 min before and 8 h after each isoproterenol injection.21 Rats in group 3 (isoproterenol group) received a subcutaneous injection of isoproterenol (100 mg/kg) for two consecutive days at an interval of 24 h; normal saline (0.5 ml) was given orally 30 min before and 8 h after each isoproterenol injection. Rats in groups 3 to 6 received a subcutaneous injection of isoproterenol (100 mg/kg) for two consecutive days at an interval of 24 h. M.vulgare extract was given orally (10, 20 and 40 mg/kg respectively) 30 min before and 8 h after each isoproterenol injection.

Sample collecting

The animals were euthanized by an overdose of the anesthetic and the hearts were removed, and blood specimens were gathered from hepatic vein. Heart tissues and serums separated from blood samples were used for biochemical analysis.

Histopathological examination

After hemodynamic measurements, the heart tissues were excised and fixed in 10% buffered formalin. The tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm and stained with Gomori Trichrome for distinguishing muscle and interstitial connective tissue to evaluate myocardial fibrosis. Myocardial fibrosis was evaluated in each section of the heart tissue using a morphometric point-counting procedure.22 Two persons graded the histopathological changes as 1, 2, 3 and 4 for low, moderate, high, and intensive pathological changes, respectively.

Creatinine Kinase - MB (CK-MB) assay

Quantitative determination of CK-MB in the rat’s serum was performed by commercially available kit (SPINREACT, Gerona, Spain) according to manufacturer’s instruction.

Neutrophil counting in blood

Prior to euthanization, venous blood samples were collected to determine the number of neutrophils in blood. Fresh blood sample was smeared on the clean lam and the percent of neutrophils were counted at 100X zooming in optical microscope after Gimsa coloring.

Myeloperoxidase assay

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) was measured in the heart tissue for quantifying the activity of neutrophils in myocardium, as previously described by Mullane et al.23 The tissue samples were homogenized (IKA Hemogenizer, Staufen, Germany) in a solution containing 0.5% hexadecyltrimethyl-ammonium bromide (HTAB) dissolved in 50 ml potassium phosphate buffer (pH=6). The samples were then centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. The samples were freeze-thawed three times and sonicated for 20 seconds. An aliquot of the supernatant (0.1 ml) or standard MPO (Sigma, Germany) was then allowed to react with 2.9 ml solution of 50 ml potassium phosphate buffer at pH 6 containing 0.167 mg of O-dianisidine hydrochloride and 0.0005% H2O2. After 5 min, the reaction was stopped with 0.1 ml of 1.2 M hydrochloric acid. The rate of change in absorbance was measured using a spectrophotometer (Cecil 9000, Cambridge, UK) at 460 nm. A standard curve (1500-25000 mU/g) was drawn using standard myeloperoxidase (Sigma, Germany) (y = 0.005x + 0.040; R2 = 0.998).

Measurements of serum TNF-α level by ELISA

The serum level of TNF-α was determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Rat TNF-αkit, IBL, Hamburg, Germany) according to the manufacturers' instruction.

Statistics

Data were presented as mean±SEM. One-way-ANOVA was used to make comparisons between the groups. When the ANOVA analysis indicated significant differences, a Student–Newman–Keulspost hoc test was performed to compare the mean values between the treatment groups and the control. Any differences between groups were considered significant at p<0.05.

Results

Phytochemical screening of M. vulgare extract

Preliminary phytochemical screening of M. vulgare extract indicated the presence of flavonoids and phenolic compounds. Besides, preliminary TLC analysis of the extract revealed the marrubiin with Rf value of 0.82 as the major compound present in the M. vulgare extract.

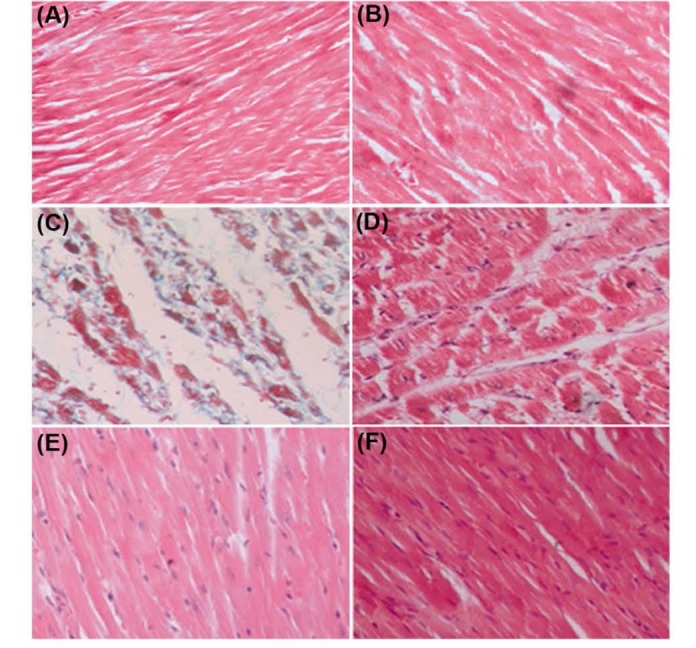

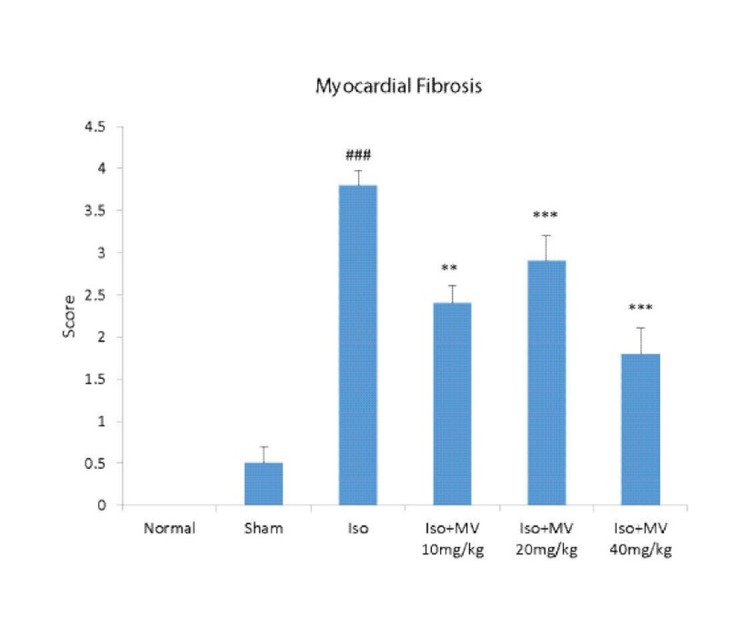

The effects of M. vulgare extract on the cardiomyocyte fibrosis

Fig. 1 shows the heart tissues after Gomori Trichrome staining. The myocardial fibers were arranged regularly with clear striations in the normal control group. No apparent degeneration or fibrosis was observed in normal control group. The histological sections of the isoproterenol treated hearts showed a severe grade of fibrosis recognized as blue-dyed parts after Gomori Trichrome staining (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 ). All three doses of M. vulgare extract dose-dependently prevented inflammatory responses and myocardial fibrosis. It was observed that treatment with methanolic extract of M. vulgare with doses of 10, 20, and 40 mg/kg reduced the isoproterenol-induced fibrosis in dose-dependent manner by 36% (p<0.01), 52 %, and 63% (p<0.001), respectively as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1 .

Photomicrographs of sections of rat cardiac apexes. A) Normal control. B) Sham (MV 40 mg/kg). C) Isoproterenol (Iso). D) Iso and MV (10 mg/kg/day). E) Iso and MV (20 mg/kg/day). F) Iso and MV (40 mg/kg/day). Heart tissue of a rat subcutaneously injected with Iso shows intensive cardiomyocyte fibrosis (blue) and increased edematous intramuscular space. Treatment with M. vulgare (MV) extract significantly prevented the fibrosis. Gomori Trichrome (40 M).

Fig. 2 .

Grading of histopathological fibrosis in the rat’s cardiac apex tissues. Grades 1, 2, 3 and 4 show low, moderate, high and intensive pathological changes, respectively. Iso: isoproterenol; MV: M. vulgare extract. Values are mean±SEM (n=4). ###p<0.001 vs. normal control, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001 as compared with isoproterenol treated group using one way ANOVA with Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test.

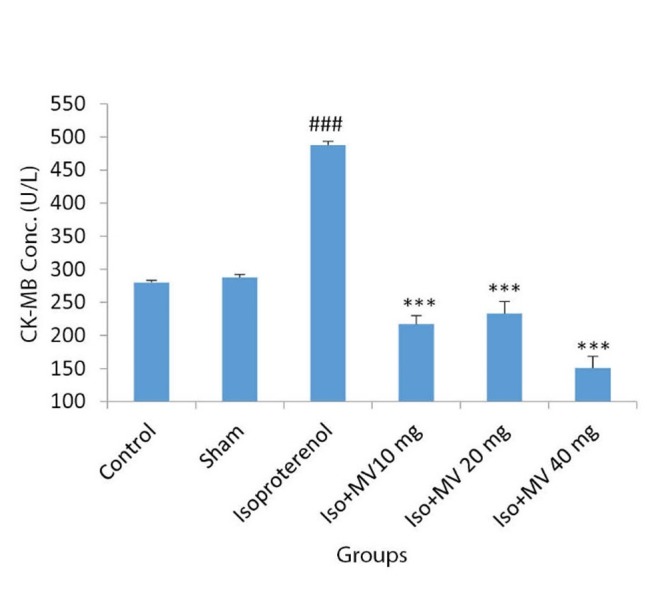

The effects of M. vulgare on the Creatine Kinase-MB isoenzyme (CK-MB) level

Serum CK-MB concentration was significantly increased from 280±3.26 in normal control to 487.5±5.7 U/L in isoproterenol treated rats (MI group) (p<0.001). M. vulgare extract alone at dose of 40 mg/kg (sham group) had no effect on the serum CK-MB level. CK-MB concentration was decreased in groups treated with 10, 20 and 40 mg/kg of M. vulgare extract by 55.4%, 52.2% and 69%, respectively, when compared with MI group (p <0.001) (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

The effects of oral administration of methanolic extract of M, vulgare on serum Creatine Kinase-MB isoenzyme (CK-MB) concentration. Iso: Isoproterenol; MV: M. vulgare extract; Values are mean±SEM (n=6). ### p<0.001 from respective control value; *** p<0.001 as compared with isoproterenol (Iso) injected group using one way ANOVA with Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test.

The effects of M. vulgare extract on the peripheral neutrophil count

The percentage of peripheral neutrophil, was significantly (p<0.001) elevated from 13±2.6% in normal control to 33.4±4.8% by isoproterenol (MI group). All doses of M. vulgare extract significantly reduced (p<0.001) the percentage of peripheral neutrophil to a normal value (Table 1).

Table 1. The effects of oral administration of the methanolic extract of M. vulgare on peripheral neutrophil count in rats.

| Groups | Control | Iso | Iso+MV 10mg/kg | Iso+MV 20mg/kg | Iso+MV 40mg/kg |

| Neutrophil count (%) | 13±2.66 | 33.4±4.8### | 15.7±3.2*** | 25.9±1.6*** | 17.7±2.65*** |

Data are expressed as mean±SEM (n=6). Iso: isoproterenol; MV: M. vulgare extract; ###p<0.05; from respective control value; ***p<0.001 as compared with isoproterenol treated group using one way ANOVA with Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test

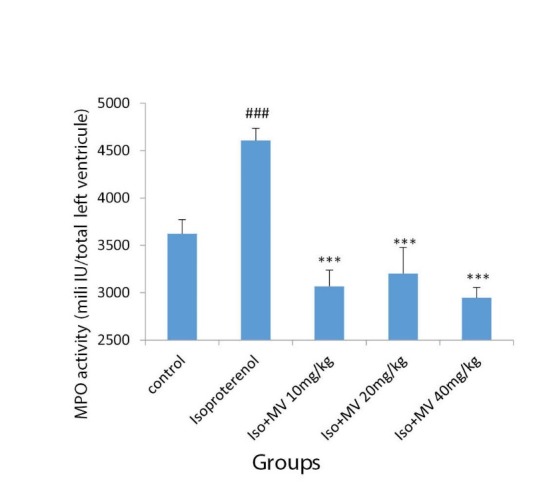

The effects of M.vulgare extract on the myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity

Isoproterenol injection to the rats caused a significant increase in neutrophil infiltration into the heart tissue, as measured by an increase in MPO activity in the myocardium (p<0.001 vs. control) (Fig. 4). The treatment of the rats with oral administration of M. vulgare extract at the doses of 10, 20, and 40 mg/kg/, reduced the enzyme activity in the heart tissue from 4605.2±130.98 mU/g wet tissue in isoproterenol group (MI) to 3067.55±171.46, 3201.78±277.2, and 2946.93±303 mU/g (p<0.001), respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The effects of oral administration of methanolic extract of M. vulgare on the myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in the heart tissue. Iso: Isoproterenol; MV: M. vulgare extract. Data are expressed as mean±SEM (n=6). ###p<0.001 from respective control value; ***p<0.001 as compared with isoproterenol treated group using one way ANOVA with Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test.

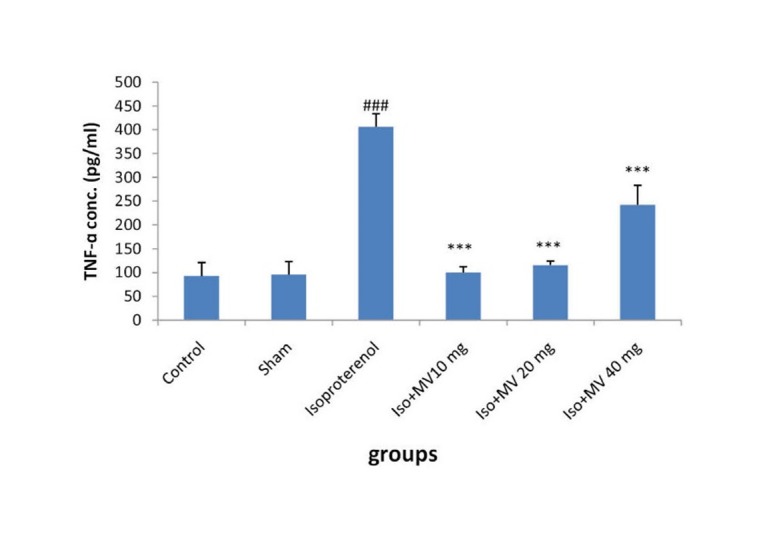

The effects of M.vulgare extract on the serum TNF-α level

It was found that the level of TNF-α in serum was profoundly increased in the isoproterenol group in comparison to the control by a mean of 442% (p<0.001) (Fig. 5 ). M. vulgare alone (40 mg/kg) in the sham group had no effect on the level of TNF-α in serum. The increased level of TNF-α by isoproterenol was markedly decreased by treatment with all doses of M. vulgare (p<0.001). The maximal effect was seen by 10 mg/kg of M. vulgare, where the concentration of TNF-α was significantly reduced from 406.15±27.8 pg/ml in the serums of MI group to 100±12.2 pg/ml (p<0.001) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The effects of oral administration of methanolic extract of M. vulgare on serum TNF-α concentration. Iso: Isoproterenol; MV: M. vulgareextract; Values are mean±SEM (n=6). ### p<0.001 from respective control value; *** p<0.001 as compared with isoproterenol injected group using one way ANOVA with Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test.

Discussion

Little is known about cardioprotective roles of M. vulgare in cardiovascular diseases. In the present study, we investigated the therapeutic effects of the methanolic extract of the aerial parts of the plant in rats with acute myocardial infarction induced by isoproterenol. Results showed cardioprotective effects of M. vulgare against isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction, as evidenced by maintaining the heart tissue architecture, improving the antioxidant defense, reducing the myocardial injury markers and suppressing the proinflammatory responses.

By administrating for a period of more than 24 h, high-dose β-agonists resulted myocardial edematous and histological changes that include myocyte necrosis, heart tissue fibrosis, myofibrilar degeneration, and leukocyte infiltration.24 The dose of isoproterenol that we used was enough to yield a considerable myocardial edematous and cardiotoxicity. Oral administration of the extract in doses of 10, 20 and 40 mg/kg for two days dose-dependently prevented myocardial injury and edematous in the isoproterenol treated rats.

Cardiomyocyte fibrosis was recognized from increased amount of interstitial connective tissue dyed blue in the Gomori Trichrome staining. Treatment with M. vulgare extract at all doses dose-dependently prevented the cardiomyocytes fibrosis, indicating the protective effect of M. vulgare on the heart tissue architecture.

Isoproterenol causes an increase in the activity of diagnostic marker enzyme and creatine kinase-MB in serum. The increased activity of this enzyme might be due to isoproterenol-induced myocardial necrosis.25 Treatment with M. vulgare extract (10, 20 and 40 mg/kg body weight) decreased the activity of serum creatine kinase-MB in isoproterenol-induced rats. But, at the dose of 40 mg/kg the extract elicited the highest significant effect on serum creatine kinase- MB activity. The CK-MB leakage is the result of the myocytes damage caused by lipid peroxidation following isoproterenol administration.25 M. vulgare extract protects myocardium by its antioxidant properties and so prevents the leakage of creatine kinase-MB.

Our preliminary phytochemical screening in this study revealed the presence of marrubiin as a major constituent in the methanolic extract of M. vulgare aerial parts. Marrubiin is a diterepene and plant diterpenes are antioxidant and scavenge oxygen free radicals. Moreover, a remarkable amount of total flavonoid and phenolic content were found in the extract. The naturally occurring flavonoids and phenolics are believed to have the ideal chemical structure for scavenging free radicals.26-28 Therefore, strong antioxidant activity of M. vulgare could be attributed to its high total phenolics and flavonoids, suggesting their role in preventing the isoproterenol-induced damages in this study.

MPO, a leukocyte enzyme, produced during myeloid differentiation in bone marrow, is stored in the primary granules of neutrophils and monocytes and is not released until leukocyte activation and degranulation.29 MPO forms free radicals and diffusible oxidants with antimicrobial activity and also leads to the promotion of lipid peroxidation and neutrophil infiltration into the site of inflammation.30 It has been suggested there is a direct relation between blood MPO level and the risk of coronary artery disease.30 Reduced MPO activity of heart tissue in the rats treated with M. vulgare extract reflects lowered neutrophil infiltration into the myocardium.

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), a proinflammatory cytokine, is revealed to be high in several myocardial injuries including myocardial infarction.31 TNF-α is associated with myocardial dysfunction by several mechanisms including altering calcium hemostasis, nitric oxide metabolism and altering gene expression by signaling through ceramide/sphingosine second messengers which leads to the production of other inflammatory cytokines, PMN proliferation and infiltration into the site of inflammation.31

In this study, animals injected with isoproterenol showed a significant increase in serum TNF-α and myocardial MPO levels demonstrative of necrosis induced inflammation of the heart tissue and neutrophil infiltration into the blood and heart tissue (as site of inflammation). Treatment with all doses of M. vulgare extract (10, 20 and 40 mg/kg), significantly decreased the level of these two inflammatory markers which shows the inhibitory effect of the extract on the neutrophil infiltration and release of the inflammatory cytokines.

The peripheral neutrophil count was carried out to assess the neutrophil infiltration into the blood. A significant elevation was seen following isoproterenol administration in the peripheral neutrophil count which reflects the inflammatory response and neutrophil infiltration promoted by isoproterenol. Polymorph nuclear leukocytes (PMNs) especially neutrophils are associated with the acute inflammatory response to tissue injury and have the capacity to produce oxygen-derived free radicals.32 The cardiotoxic effect of free radicals is well documented.33,34 In addition, PMN-derived free radicals are demonstrated to be cytotoxic against endothelial cells.34 Epidemiological studies have demonstrated the total white blood cell count to be an independent risk factor for ischemic heart disease. Furthermore, the leukocyte count may be positively correlated to the extent of coronary artery disease and risk of coronary recurrence after myocardial infarction.35 The cardioprotective potential of PMN inhibition in intact animals subjected to myocardial infarction has been widely used to indirectly assess the role of PMNs.36 Oral administration of M. vulgare extract reduced the number of blood neutrophils, indicating the inflammatory response suppression activity of the extract.

The significant decrease of the peripheral blood neutrophil count might be considered as a result of MPO and TNF-α inhibitory role of M. vulgare.

According to our previous study in which the administration of the methanolic extract of M. vulgare on the electrocardiography and hemodynamic changes was investigated, it was found that the extract substantially restored the changes and normalized the ECG pattern.37 For example, the extract at the applied doses (10, 20 and 40 mg/kg) prevented the ST-segment elevation and R-amplitude suppression. Moreover, hemodynamic parameters such as left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP) which was markedly increased after isoproterenol injection was lowered in the treatment groups.37 Furthermore, the decreased values of the left ventricular contractility (LVdP/dtmax) and relaxation (LVdP/dtmin) were significantly restored by all the doses of M. vulgare extract (p<0.001).37

The result of quantitative evaluation of marrubiin (unpublished data) in which marrubiin in the extract was calculated as 156 mg/g of M. vulgare extract, corroborated the qualitative method which proved the presence of marrubiin.

In addition to marrubiin, some compounds isolated from the aerial parts of M. vulgare such as glycosidic phenylpropanoid esters have been shown to inhibit the cyclooxygenase enzyme (COX) and have anti-inflammatory potential. Hence, the anti-inflammatory activity of M. vulgare extract seen in our study could be attributed to the presence of such compounds.12,18

It is well-documented that natural diterpenes are able to change the transcription of different genes and change the production or activity of important molecules.38 For example, some diterpenes are being used for their anticancer potential.38 Therefore, it could be proposed that diterpenes in the M. vulgare extract, like marrubiin, have the potential to change the production of some molecules involved in the process of inflammation such as TNF-α and MPO; however, further studies are needed to support this hypothesis.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrated that the methanolic extract of M. vulgare inhibited the inflammatory response following isoproterenol injection by decreasing proinflammatory markers. Also it maintained the structure and architecture of cardiac cells by decreasing the cardiac tissue damage and strengthening the myocardial membrane as evidenced by histopathological findings of myocardium. Regarding the results of our previous work, after further studies, if the beneficial effects of M. vulgare extract could be reproduced in human beings, our findings may introduce a novel therapy for prevention and treatment of myocardial infarction.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by a grant from the Research Vice Chancellor of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Ethical issues

This study was performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz-Iran (National Institutes of Health publication No 85-23, revised 1985).

Competing interests

The authors of the present work certify that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Benjamin IJ, Jalil JE, Tan LB, Cho K, Weber KT, Clark WA. Isoproterenol-induced myocardial fibrosis in relation to myocyte necrosis. Cir Res. 1989;65:657. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frangogiannis NG, CW CWS, Entman ML. The inflammatory response in myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53:31–47. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00434-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gharacholou SM, Lopes RD, Alexander KP, Mehta RH, Stebbins AL, Pieper KS. Age and outcomes in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention: Findings from the APEX-AMI trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:559–67. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumann H, Gauldie J. The acute phase response. Immunol Today. 1994;15:74–80. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss SJ. Tissue destruction by neutrophils. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:365–776. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198902093200606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lucchesi BR, Werns SW, Fantone JC. The role of the neutrophil and free radicals in ischemic myocardial injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1989;21:1241–51. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(89)90670-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harvey AL. Natural products in drug developmen. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:894–901. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler MS. Natural products to drugs: natural product-derivedcompounds in clinical trials. Nat Prod Rep. 2008;25:475–516. doi: 10.1039/b514294f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Upaganlawar A, Gandhi H, Balaraman R. Isoproterenol induced myocardial infarction: Protective role of natural products. Journal of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2011;6:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrade-Cetto A, Heinrich M. Mexican plants with hypoglycaemic effect used in the treatment of diabetes. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;99:325–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elberry AA, HarrazFM HarrazFM, Ghareib SA, Gabr SA, Nagy AA, Abdel-Sattar E. Methanolic extract of Marrubium vulgare ameliorates hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Int J Diabetes Mellit. 2011:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mnonopi N, Levendal RA, Davies-Coleman MT, Frost CL. The cardioprotective effects of marrubiin, a diterpenoid found in Leonotis leonurus extracts. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;138:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stulzer HK, Tagliari MP, Zampirolo JA, Cechinel-Filho V, Schlemper V. Antioedematogenic effect of marrubiin obtained from marrubium vulgare. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;108:379–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Jesus RAP, Cechinel-Filho V, Oliveira AE, Schlemper V. Analysis of the antinociceptive properties of marrubiin isolated from marrubium vulgare. Phytomedicine. 2000;7:111–5. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(00)80082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlemper V, Ribas A, Nicolau M, Cechinel Filho V. Antispasmodic effects of hydroalcoholic extract of Marrubium vulgare on isolated tissues. Phytomedicine. 1996;3:211–6. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(96)80038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El Bardai S, Hamaide M-C, Lyoussi B, Quetin-Leclercq Jl, Morel N, Wibo M. Marrubenol interacts with the phenylalkylamine binding site of the L-type calcium channel. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;492:269–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matkowski A, Piotrowska M. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging activities of some medicinal plants from the Lamiaceae. Fitoterapia. 2006;77:346–53. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sahpaz S, Garbacki N, Tits M, Bailleul Fo. Isolation and pharmacological activity of phenylpropanoid esters from Marrubium vulgare. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;79:389–392. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rona G. Catecholamine cardiotoxicity. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1985;17:291–306. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(85)80130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Popa DP, Salei LA. Diterpenoids of the genus Marrubium (horehound) Rastitel’nye Resursy. 1973;9:384–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garjani A, Andalib S, Biabani S, Soraya H, Doustar Y, Garjani A. et al. Combined atorvastatin and coenzyme Q10 improve the left ventricular function in isoproterenol-induced heart failure in rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;666:135–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stanely-Mainzen-Prince P. A biochemical, electrocardiographic, electrophoretic, histopathological and in vitro study on the protective effects of (−)epicatechin in isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarcted rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;671:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mullane KM, Kraemer R, SmithB SmithB. Myeloperoxidase activity as a quantitative assessment of neutrophil infiltration into ischemic myocardium. J Pharmacol Methods. 1985;14:157–67. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(85)90029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piper RD, Li FY, Myers ML, Sibbald WJ. Effects of isoproterenol on myocardial structure and function in septic rats. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1999;86:993. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.3.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel V, Upaganlawar A, Zalawadia R, Balarman R. Cardioprotective effect of melatonin against isoproterenol induced myocardial infarction in rats: A biochemical, electrocardiographic and histoarchitectural evaluation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;644:160–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi CW, Kim SC, Hwang SS, Choi BK, Ahn HJ, Lee MY. et al. Antioxidant activity and free radical scavenging capacity between Korean medicinal plants and flavonoids by assay-guided comparison. Plant Sci. 2002;163:1161–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pukalskas A, Venskutonis PR, Salido S, Waard Pd, van Beek TA. Isolation, identification and activity of natural antioxidants from horehound (Marrubium vulgare L) cultivated in Lithuania. Food Chem. 2012;130:695–700. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skerget M, Kotnik P, Hadolin M, Hras AR, Simonic M, Knez Z. Phenols, proanthocyanidins, flavones and flavonols in some plant materials and their antioxidant activities. Food Chem. 2005;89:191–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malech HL, Nauseef WM. Primary inherited defects in neutrophil function: ethiology and treatment. Semin Hematol. 1997;34:279–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang R, Brennan ML, Fu X, Aviles RJ, pearce GL, Penn MS. et al. Association between Myeloperoxidase levels and risk of coronary artery disease. JAMA. 2001;286:2136–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.17.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramani R, Mathier M, Wang P, Gibson G, Tögel S, Dawson J. et al. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor receptor-1-mediated pathways has beneficial effects in a murine model of postischemic remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:1369–77. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00641.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baumann H, Gauldie J. The acute phase response. Immunol Today. 1994;15:74–80. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burton KP. Evidence of direct toxic effects of free radicals on the myocardium. Free Radic Biol Med. 1988;4:15–24. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(88)90006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss SJ. Tissue destruction by neutrophils. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:365–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198902093200606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Badwey JA, Karnovsky ML. Active oxygen species and the functions of phagocytic leukocytes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1980;49:695–726. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.003403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lucchesi BR, Werns SW, Fantone JC. The role of the neutrophil and free radicals in ischemic myocardial injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1989;21:1241–51. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(89)90670-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yousefi K, Soraya H, Fathiazad F, Khorrami A, Hamedeyazdan S, Maleki-Dizaji N. et al. Cardioprotective effect of Marrubium vulgare Lon isoproterenol induced acute myocardial infarction in rats. Indian J Exp Biol. 2013;51:653–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tu WC, Wang SY, Chein SC, Lin FM, Chen LR, Chiu CY. et al. Diterpenes from Cryptomeria japonica inhibit androgen receptor transcriptional activity in prostate cancer cells. Planta Med. 2007;73:1407–1409. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-990233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]