Abstract

IL-22 is an epithelial cell survival cytokine that is currently under development for the treatment of acute liver damage. Here, we used a mouse model of renal ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury to investigate whether IL-22 has therapeutic potential for the treatment of AKI. The action of IL-22 is mediated by binding to IL-22R1 and leads to STAT3 activation. Under physiologic conditions, renal expression of IL-22R1 was detected only in the brush border of the renal proximal tubular epithelial cells (RPTECs). Renal I/R elevated serum IL-22 levels slightly but did not induce STAT3 phosphorylation in RPTECs. IL-22–deficient mice had slightly increased I/R-induced injury compared with wild-type mice. In contrast, treatment with IL-22 or overexpression of IL-22 by either gene targeting (IL-22 transgenic mice) or administration of adenovirus expressing IL-22 increased STAT3 phosphorylation in RPTECs, ameliorated I/R-induced renal inflammation and tubular cell injury, and preserved renal functions. Overexpression of IL-22 increased the phosphorylation of STAT3 and Akt, upregulated antiapoptotic genes (e.g., Bcl-2), and downregulated proapoptotic genes (e.g., Bad) in the kidneys of mice subjected to I/R. Notably, phosphorylation of Akt increased and expression of Bad decreased in proximal tubular cells under these conditions. Furthermore, compared with wild-type mice, IL-22 transgenic mice had increased survival rates, whereas IL-22–deficient mice had reduced survival rates after I/R injury. In summary, renal expression of IL-22R1 is restricted to RPTECs, and treatment with IL-22 protects against renal I/R injury by activating STAT3 and AKT, suggesting that IL-22 has therapeutic potential for the treatment of AKI.

IL-22, a member of the IL-10 family, is mainly produced by innate lymphoid cells, Th17 cells, and Th22 cells.1,2 The functions of IL-22 are mediated by binding to IL-10R2 and IL-22R1. IL-10R2 is ubiquitously expressed in many types of cells, whereas IL-22R1 is mainly expressed in epithelial cells from the gastrointestinal tract and skin, as well as liver and kidney, but is absent on immune cells.2,3 Exclusively secreted by leukocytes but targeting foremost cells of epithelial origin, IL-22 plays important roles in promoting antimicrobial immunity and tissue repair by predominantly activating signal transducer and transcription factor 3 (STAT3).4 Accumulating evidence suggests that IL-22 possess antiapoptotic, proproliferative, and proregenerative functions.5 Specifically, treatment with IL-22 associates with tissue protection and/or regeneration in murine models of lung injury, pancreatitis, and liver damage.5 IL-22R1 expression was detected in the kidneys; however, what types of cells in the kidneys express this receptor and whether or not IL-22 also has a protective effect against kidney injury remain unknown.3

AKI is a severe disorder with a rapid (ranging from hours to weeks to less than 3 months) decrease in kidney function, which occurs in 2%–7% of hospitalized patients and 5%–10% of the intensive care unit population.6–8 AKI is often associated with multiorgan disease and sepsis.6–8 For example, high incidence of AKI is frequently observed in alcoholic cirrhosis and alcoholic hepatitis patients, and AKI is an early predictor of mortality for those patients.9,10 Despite recent progress in renal replacement therapy and critical care medicine, AKI is still associated with high morbidity and mortality, particularly in those patients admitted to the intensive care unit.6–8 Thus, it is still urgently needed to study the pathogenesis of AKI and search for novel therapies. AKI can result from many reasons, such as reduced renal perfusion without cellular injury, tubular cell necrosis or apoptosis caused by an ischemic, toxic, or obstructive insult, a tubulointerstitial process with inflammation and edema, or a primary decrease in the filtering capacity of the glomerulus.6–8 Among those injurious stimuli, renal ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury is a common cause of AKI, which causes the damage of the renal tubular epithelia, especially the proximal tubular cells.6–8 Here, we conducted the preclinical study to examine the effects of IL-22 on renal I/R injury in mice, and our findings showed that IL-22 was very effective to prevent renal I/R injury, suggesting that IL-22 had therapeutic potential for the treatment of AKI.

Results

IL-22R1 Is Expressed in Renal Proximal Tubular Epithelial Cell Brush Border

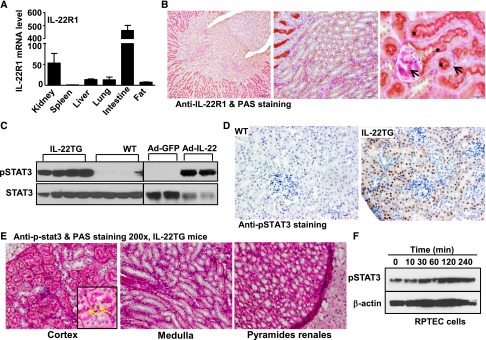

IL-22 exerts its biologic effects through heterodimeric transmembrane receptor complexes composed of IL-10R2 and IL-22R1. IL-10R2 is ubiquitously expressed and recognized by both IL-10 and IL-22. Therefore, IL-22 responsiveness is determined by the expression of IL-22R1.4 Real-time PCR analyses of IL-22R1 gene expression in various tissues indicated that IL-22R1 levels were highest in the intestine followed by the kidney, liver, lung, and fat (Figure 1A). Double staining with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining and anti–IL-22R1 antibody indicated that the IL-22R1 protein was mainly expressed in the brush border of renal proximal tubular epithelial cells (RPTECs) but not in other types of cells in the kidneys (Figure 1B). Increased expression of activated phospho STAT3 (pSTAT3) was detected in renal tissues from mice with IL-22 overexpression (e.g., IL-22 transgenic [IL-22TG] mice or IL-22–expressing adenovirus [Ad-IL-22] –infected mice) determined by Western blot (Figure 1C) and anti-pSTAT3 staining (Figure 1D), which suggested that the expression of IL-22R1 in the kidneys is functional. In agreement with the IL-22R1 expression, activation of pSTAT3 was only detected in the proximal tubular cells (with PAS-positive brush border) from IL-22TG mice (Figure 1E). Finally, treatment with IL-22 protein significantly increased pSTAT3 level in cultured human RPTECs (Figure 1F).

Figure 1.

IL-22R1 is predominantly expressed in the proximal renal tubular epithelial cells. (A) Real-time PCR analyses of IL-22R1 gene expression in various tissues of WT mice. (B) Representative images of PAS staining (arrows pointing to pink) and immunohistochemistry staining (brown) of anti–IL-22R1 in renal tissue of WT mice. The proximal tubule brush was double stained with anti–IL-22R1 (brown) and PAS (pink), and it is shown in orange (asterisk). (C) Western blot analyses of anti-pSTAT3 and STAT3 protein in renal tissues of WT and IL-22TG mice or mice infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-IL-22. (D) Representative images (original magnification, ×200) of immunohistochemistry staining of pSTAT3 in renal tissues of WT and IL-22TG mice. Note that pSTAT3 staining was only detected in the tissues from IL-22TG as indicated by dark brown nucleus staining. (E) Representative images of immunohistochemistry staining of anti-pSTAT3 (arrows pointing to brown) and PAS staining in renal tissues of IL-22TG mice. (F) Human RPTECs were treated with human IL-22 (100 ng/ml) for the indicated time, and pSTAT3 levels were determined by Western blot analyses.

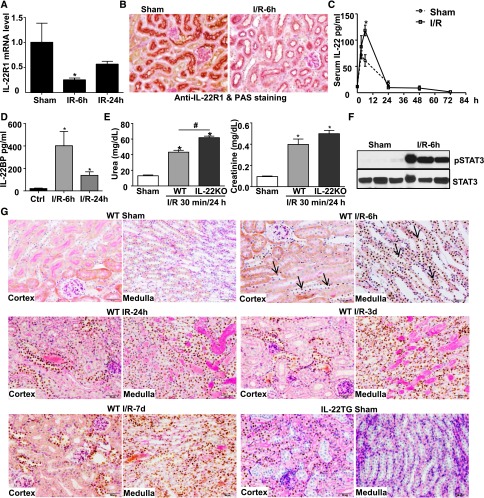

Endogenous IL-22 Plays a Role in Modulating Renal I/R Injury

Compared with sham mice, renal IL-22R1 mRNA (Figure 2A) and protein (Figure 2B) levels were decreased after renal I/R. In normal mice, serum IL-22 was maintained at a low level (∼10 pg/ml), and it was significantly elevated after surgical stress (sham operation group) and renal I/R injury, with the peak levels of ∼60 and ∼120 pg/ml, respectively; then, serum IL-22 reduced to normal levels within 24 hours (Figure 2C). Similarly, IL-22 binding protein (IL-22BP) was also increased after renal I/R (Figure 2D). Furthermore, IL-22 knockout (IL-22KO) mice exhibited a slight increase in serum urea and creatinine after renal I/R compared with wild-type (WT) mice (Figure 2E). The difference in serum urea reached statistical significance between WT and IL-22KO mice after 30 minutes of I/R (Figure 2E) but did not reach statistical significance after 40 minutes of I/R (data not shown). Interestingly, although endogenous IL-22 levels were elevated and pSTAT3 activation was increased in the renal tissues (Figure 2F), pSTAT3 was not detected in the RPTECs of IL-22 target cells after reperfusion for 6 hours to 7 days (Figure 2G), suggesting that the increased endogenous IL-22 was not sufficient to activate STAT3 in the RPTECs. Surprisingly, pSTAT3 activation was detected in other types of renal tubular cells other than RPTECs, such as the tubular cells in medulla, after reperfusion for 6 hours to 7 days (Figure 2G). In contrast, strong pSTAT3 was detected in RPTECs from IL-22TG mice, even without I/R (sham group) (Figure 2G).

Figure 2.

Endogenous IL-22 may play a role in protecting against renal I/R injury. (A–D) WT mice underwent sham operation or were subjected to 40 minutes of renal I/R for the indicated time. (A) IL-22R1 gene expression was analyzed by real-time PCR (n=3 mice). (B) Representative PAS and immunohistochemistry staining of anti–IL-22R1 in the renal tissues from sham or 6-hour I/R-treated mice is shown. (C) Serum IL-22 levels were measured by an ELISA kit. (D) Serum IL-22BP levels were measured by an ELISA kit (n=6 mice). (E) IL-22KO and WT mice were subjected to 30 minutes of renal ischemia and 24 hours of reperfusion. Serum urea and creatinine levels were determined (n=3–4 mice). (F) Western blot analyses of pSTAT3 and STAT3 in renal tissues after I/R for 6 hours. (G) Representative PAS (pink) and immunohistochemistry staining of pSTAT3 (arrows indicate representative positive staining) in the renal tissues from sham or I/R-treated mice is shown. *P<0.05 versus sham or control (Ctrl) group; #P<0.05 as indicated.

IL-22 Treatment or IL-22 Overexpression Preserves Renal Function and Decreases Renal Injury after I/R

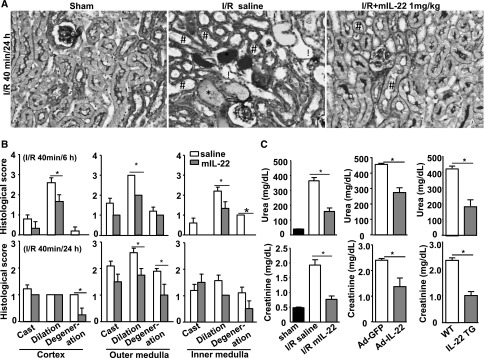

To explore the potential therapeutic role of IL-22 in renal I/R injury, C57BL/6N mice were subjected to sham operation or renal I/R with intraperitoneal injection of saline or recombinant mouse IL-22 protein (mIL-22; 1.0 mg/kg) 30 minutes before surgery, and the peak levels of mIL-22 occurred after ∼15–60 minutes of injection (Supplemental Figure 1). As shown in Figure 3, A and B, the renal damage was less pronounced in the I/R group with mIL-22 administration than the I/R group with saline treatment. At 6 or 24 hours after I/R, mIL-22–treated mice showed less tubulointerstitial injury in the cortex, outer medulla, and inner medulla by all three criteria examined (i.e., tubular cast formation, dilation, and degeneration) (Figure 3B). The increases of serum urea and creatinine levels at 24 hours of reperfusion were significantly suppressed in mIL-22–treated mice as well as Ad-IL-22–administered mice and IL-22TG mice (Figure 3C). Interestingly, when mIL-22 was administered at the beginning of reperfusion, it also exhibited protective effects on renal I/R injury, although the efficacy was much lower compared with the efficacy when mIL-22 was injected before renal I/R (Supplemental Figure 2, A and B).

Figure 3.

Treatment with IL-22 ameliorates renal I/R injury. (A and B) Mice were subjected to sham operation (sham; n=8) or renal ischemia (40 minutes) and reperfusion for 6 or 24 hours. The I/R mice were intraperitoneally injected with saline or recombinant mIL-22 (1.0 mg/kg) 30 minutes before surgery. (A) Representative images (original magnification, ×200) of PAS staining of the kidneys after I/R for 24 hours. Tube cast (*), dilation (#), and degeneration (!) are indicated. (B) Histologic changes were evaluated by assessment of the extent of cast formation, tubular dilation, and tubular degeneration in the cortex, outer medulla, and inner medulla at 6 (n=4 mice for saline, n=3 mice for mIL-22) and 24 hours (n=7 mice for saline, n=4 mice for mIL-22) of reperfusion. (C) Serum urea and creatinine levels were measured at 24 hours of reperfusion from mice treated with mIL-22 (n=7 mice for saline, n=4 mice for mIL-22), mice injected intravenously with Ad-GFP or Ad-IL-22 (n=3 mice each), or mice with IL-22 overexpression (IL-22TG; n=8 mice for WT, n=10 mice for IL-22TG). *P<0.05.

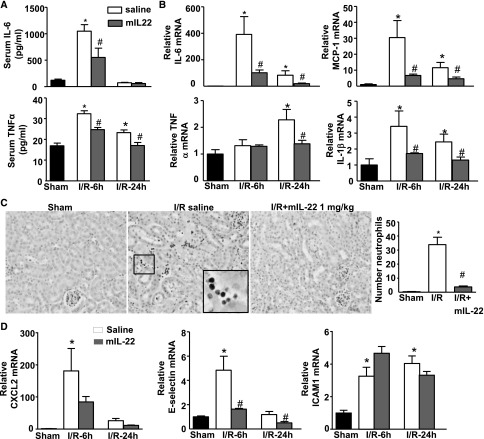

IL-22 Treatment Attenuates Systemic and Renal Inflammation after Renal I/R in Mice

To get insight into the mechanism of IL-22–mediated protection against I/R injury, systemic and renal inflammations were analyzed. I/R induced ∼10- and ∼2-fold increases of serum IL-6 and TNFα at 6 hours after I/R, respectively, and mIL-22 administration significantly attenuated the increases of serum IL-6 and TNFα compared with saline control (Figure 4A). Furthermore, the renal mRNA levels of IL-6, MCP-1, IL-1β, and TNFα were increased at 6 and 24 hours after I/R, and mIL-22 treatment significantly suppressed the expression of these genes (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

IL-22 treatment attenuates systemic and renal inflammation after renal I/R. Mice were treated as described in Figure 3. (A) Serum IL-6 and TNFα were determined 6 and 24 hours post-I/R. (B) Relative mRNA levels of cytokines were determined by real-time PCR in renal tissues after reperfusion for 6 or 24 hours. (C) Representative images of immunohistochemistry staining of anti-MPO show the infiltration of neutrophils into the tubulointerstitium from the I/R saline group. The number of neutrophils per field (×200) were accounted. (D) Relative mRNA levels of neutrophil infiltration-related genes, including CXCL2, E-selectin, and ICAM1, were analyzed by real-time PCR in the kidney after reperfusion for 6 or 24 hours. *P<0.05 versus sham group; #P<0.05 versus corresponding saline group.

Renal I/R injury is characterized by a massive influx of neutrophils early after reperfusion, which play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of postischemic renal failure through the release of cytotoxic proteases and oxygen-derived radicals.11 The influx of Myeloperoxidase+ (MPO+) neutrophils to the ischemic kidneys was increased at 6 hours of reperfusion, and mIL-22 treatment attenuated the MPO+ neutrophil infiltration into the tubulointerstitium (Figure 4C). Next, we examined the effects of several chemokins and adhesion molecules that are required for neutrophil recruitment post-I/R kidney injury. As illustrated in Figure 4D, real-time PCR analyses revealed that the expressions of CXCL2, E-selectin, and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) were upregulated in the kidneys 6 hours after I/R, and treatment with mIL-22 markedly prevented the I/R-mediated upregulation of CXCL2 and E-selectin but did not affect ICAM1 expression (Figure 4D).

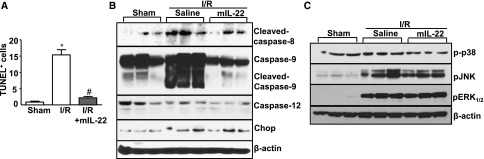

IL-22 Treatment Ameliorates Renal Tubular Epithelial Cell Apoptosis

Apoptosis plays an important role in I/R tubular injury. To determine whether IL-22 treatment affects renal tubular cell apoptosis after I/R, renal tissue sections were examined by performing terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated digoxigenin-deoxyuridine nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining. As illustrated in Figure 5A and Supplemental Figure 3, the number of TUNEL-positive tubular cells was significantly increased in the I/R group with saline treatment but markedly reduced in the I/R group with mIL-22 treatment. Furthermore, I/R upregulated the expression of apoptosis-related caspase proteins levels, including cleaved caspase-8 and -9. This increase was prevented in mIL-22–treated mice. In contrast, expression of endoplasmic reticulum stress-related proteins, including caspase-12 and C/EBP homologous protein (Chop), was unchanged after IL-22 treatment (Figure 5B). In addition, renal I/R strongly activated several intracellular signals, including phospho c-Jun N-terminal kinase and phospho extracellular signal–regulated kinase (pERK); however, IL-22 treatment did not further affect the activation of these signaling pathways at 6 hours of reperfusion (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

IL-22 treatment reduces renal tubule epithelial cell apoptosis. Mice were treated as described in Figure 3. (A) The number of TUNEL-positive tubular cells per field (×400) was counted (n=4–8). *P<0.05 versus sham; #P<0.05 versus I/R. (B) Western blot analyses of caspase-8, -9, and -12 and Chop levels in renal tissues after I/R for 6 hours. (C) Western blot analyses of p-p38, phospho c-Jun N-terminal kinase (pJNK), and pERK1/2 levels in renal tissues after I/R for 6 hours.

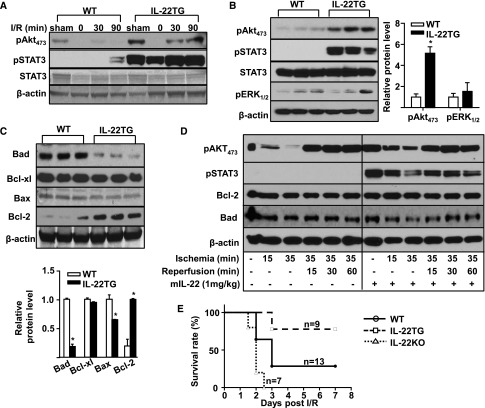

IL-22 Overexpression Activates Cell Survival Signals (Akt and STAT3) in the Kidneys and Increases the Survival Rate after Renal I/R

The above data suggest that IL-22 treatment ameliorates I/R-induced apoptosis in the kidneys. To investigate the mechanisms by which IL-22 attenuates apoptosis in renal I/R injury, we examined the cell survival signals, such as Akt and STAT3. As illustrated in Figure 6A, weak pAkt473 expression was detected in the sham-treated kidneys, and this expression was decreased after I/R in WT mice. Compared with WT mice, expression of pAkt473 was much higher in IL-22TG mice at both sham and I/R groups (Figure 6A). Interestingly, pAkt473 was lower in the 0-hours reperfusion group than the sham group. This result may be because there was no blood flow; also, IL-22 levels were significantly decreased in the ischemic kidney.

Figure 6.

IL-22 activates Akt and inhibits mitochondrial apoptosis. (A) WT and IL-22TG mice were subjected to sham operation or renal I/R for the indicated time, and then, pAkt473, pSTAT3, STAT3, and β-actin levels were detected by Western blot in renal cortex tissues. (B) Western blot analyses of pAkt473, pSTAT3, STAT3, pERK1/2, and β-actin levels in renal cortex tissues of WT and IL-22TG mice. Relative protein levels of pAkt473 and pERK1/2 were determined. (C) Western blot analyses of mitochondrial apoptosis-related proteins, including Bad, Bcl-xl, Bax, and Bcl-2, in renal cortex tissues of WT and IL-22TG mice (β-actin was loading control). n=3 mice. (D) Western blot analyses of pAkt473, pSTAT3, Bcl-2, Bad, and β-actin levels in renal cortex tissues of normal mice or mice treated with or without IL-22. (E) IL-22TG (n=9), IL-22KO (n=7), and WT (n=13) mice were assigned to left renal ischemia (40 minutes) after right nephrectomy. The difference in survival rate among the three groups was statistically significant (P<0.05). *P<0.05 versus WT group.

In contrast to strong pSTAT3 expression 6 hours post-I/R (Figure 5C), pSTAT3 expression was not detected 30 minutes post-I/R and weakly elevated 90 minutes post-I/R in WT mice (Figure 6A). As expected, strong pSTAT3 expression was detected in the kidneys from IL-22TG before or after I/R. Moreover, Western blot analyses of renal cortex tissues revealed that expression of pAkt473 and pSTAT3 (but not pERK1/2) was significantly increased in renal cortex tissues from IL-22TG mice compared with WT mice (Figure 6B). Accordingly, the expression of antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 was increased, whereas the expression of proapoptotic proteins Bad and Bax was downregulated in the renal cortex tissues from IL-22TG mice versus WT mice (Figure 6C). More importantly, in situ immunohistochemistry staining revealed that the expression of pAkt473 was increased, whereas the expression of Bad protein was decreased in the proximal tubular cells of kidneys from IL-22TG compared with WT mice (Supplemental Figure 4A). Similarly, treatment of mice with mIL-22 also increased pAkt473, pSTAT3, and Bcl-2 levels but decreased Bad levels in normal or I/R renal tissues (Figure 6D).

To further confirm the therapeutic efficacy of IL-22 in renal I/R injury, IL-22TG, IL-22KO, and WT mice were assigned to left renal ischemia (40 minutes) after right nephrectomy, and the survival rate was determined. As illustrated in Figure 6E, the survival rates at day 7 after reperfusion in IL-22TG and WT mice were 77.8% and 28.6%, respectively, and all of the IL-22KO mice died within 3 days. The differences in survival rates among the three groups were statistically significant.

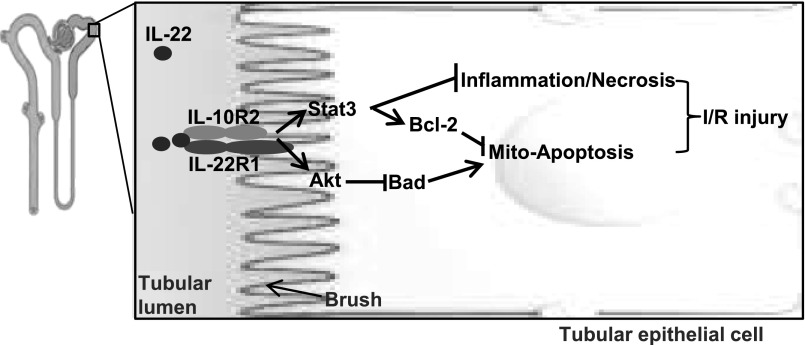

Discussion

Numerous preclinical studies have been conducted in recent years to explore the therapeutic potential of recombinant IL-22 for the treatment of liver, pancreatic, intestinal, and lung disorders that are associated with epithelial injury.5 Recombinant IL-22 is currently under development for the treatment of acute liver failure (Generon Corporation, Shanghai, China). In the current study, we provide in vivo evidence for the first time that administration of recombinant IL-22 or overexpression of IL-22 by injection of Ad-IL-22 or gene targeting ameliorates renal I/R injury and preserves renal functions by activating STAT3 and AKT in the proximal tubular epithelial cells (Figure 7). This finding suggests that IL-22 may also have therapeutic potential for the treatment of AKI, such as renal I/R injury.

Figure 7.

A model illustrating the protective effects of IL-22 on renal I/R injury. IL-22 activates STAT3 and Akt in the proximal tubular cells, which is followed by the upregulation of Bcl-2, downregulation of Bad, and inhibition of inflammation, thereby ameliorating renal I/R injury.

IL-22R1 Is Expressed in the Proximal Tubular Epithelial Cells, Which Are the Most Sensitive to I/R Injury

The pathophysiology of renal I/R injury comprises a complex sequential interplay between tubular and endothelial cell damage, inflammation, and microvascular blood flow. The initial region affected by I/R injury is the proximal tubule, which is the most sensitive to ischemic damage.12 Simultaneously, I/R injury triggers an inflammatory response13 and subsequently attracts neutrophil and macrophage infiltration into the tubulointerstitium, leading to kidney damage and development of fibrosis.14–16 Although renal tubular epithelial cell injury from ischemia has been generally thought to be a result of the necrotic form of cell death, many studies suggest that apoptosis also significantly contributes to ischemic renal dysfunction, and it is likely that the cascades that lead to apoptotic or necrotic modes of cell death are activated almost simultaneously and share some common pathways. It has been well documented that Akt-mediated restriction of mitochondrial apoptotic pathways plays important roles in attenuating tubular cell apoptosis.17,18

Interestingly, IL-22R1 expression was mainly detected in the proximal tubules, which are the most sensitive to I/R injury. IL-22R1 expression was not detected in the other types of epithelial cells other than the RPTECs within kidneys. The mechanisms by which IL-22R1 is only expressed in the RPTECs, but not other types of epithelial cells in the kidneys, are not clear. In agreement with the IL-22R1 expression, STAT3 and AKT activations were also detected in the RPTECs but not other types of epithelial cells in the kidneys after IL-22 overexpression (Figures 1 and 6). These findings suggest that IL-22 specifically targets the RPTECs in the kidneys, thereby ameliorating renal I/R injury.

Endogenous IL-22 Plays a Role in Protecting against Renal I/R Injury

In the current study, we showed that serum IL-22 levels were elevated after renal I/R and that IL-22KO mice had a slight but significant increase in serum urea levels 30 minutes after renal I/R compared with WT mice (Figure 2E). Serum creatinine levels were comparable between WT and IL-22KO mice after renal I/R injury (Figure 2E). Additionally, IL-22KO mice had a significantly lower survival rate compared with WT mice 7 days after renal I/R (Figure 6). Collectively, these findings suggest that endogenous IL-22 plays a role in preserving renal function during early stages of renal I/R but may have a more important role in protecting against renal I/R injury during the late stages. This finding is likely, because IL-22BP levels are elevated during the early stages of renal I/R (Figure 2D), which attenuates IL-22 functions; also, sufficient time is needed for intrinsic renal cells or recruited immune cells to produce IL-22 and the RPTECs to respond to it. Despite the fact that serum IL-22 levels were elevated after I/R, significant pSTAT3 activation was not detected in the RPTECs. This finding indicates that the modulatory potential of the IL-22/STAT3 axis in the kidneys is not saturated by endogenous IL-22, which consequently raises the possibility for the application of this cytokine in the treatment of renal I/R injury. Indeed, administration of recombinant IL-22 or overexpression of IL-22 by injection of Ad-IL-22 or gene targeting markedly activated STAT3 in the RPTECs, significantly ameliorated renal I/R injury, and preserved renal function (Figures 1–3) (see discussion below).

IL-22 Treatment Ameliorates Renal I/R Injury by Activating STAT3 and Akt Signaling Pathways

The beneficial effects of IL-22 in organ injury have been shown previously in several models of liver injury, lung injury, and pancreatitis.5 Particularly, the hepatoprotective effects of IL-22 have been extensively investigated. It has been shown that administration of recombinant IL-22 significantly alleviates murine hepatic injury in response to concanavalin A, alcohol, acetaminophen, I/R, or other insults by ameliorating hepatocyte damage (reviewed in ref. 5). In addition, IL-22 also targets hepatic stellate cells19 and liver progenitor cells,20 thereby inhibiting liver fibrosis and promoting liver regeneration, respectively. Accumulating evidence suggests that STAT3 is a major downstream signal of IL-22 and mediates its hepatoprotective functions by upregulating the expression of antiapoptotic genes (e.g., Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Mcl-1) and mitogenic genes (e.g., Cyclin D1). In addition, IL-22 also activates Akt and ERK1/2 (to a lesser extent), which may also contribute to the antiapoptotic and proliferative functions of IL-22.21,22 In the current study, we showed that activation of STAT3 and Akt but not ERK1/2 was detected in the RPTECs from mice with IL-22 overexpression. This activation was accompanied with increased Bcl-2 levels and decreased Bad levels, which are likely the molecular basis for the protective effects of IL-22 on I/R-induced renal injury.

I/R and IL-22 Activate STAT3 in Different Types of Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells

Signaling through the JAK/STAT pathway is important for the kidney’s response to injury and the progression of certain renal diseases, including diabetic nephropathy, renal fibrosis, HgCl2-induced AKI, and renal I/R injury.23 It has been shown that the JAK2/STAT1/3 signals were activated in the kidneys after I/R and that blockage of JAK2 by AG490 attenuates I/R-induced renal injury. However, the localization of JAK/STAT activation is not known.24 In this study, we showed that activation of pSTAT3 was strongly detected in the kidneys after I/R (Figure 2E). Also, in situ immunohistochemistry staining of pSTAT3 showed that activation of STAT3 was observed in all types of the tubular epithelial cells except the proximal tubular epithelial cells, which was in contrast to the IL-22–mediated specific activation of STAT3 in the proximal tubular epithelial cells (Figure 2F). Activation of STAT3 by ATP depletion or H2O2 promotes the survival of human and mouse RPTECs in vitro.25,26 Thus, IL-22–mediated specific activation of STAT3 in the RPTECs likely prevents RPTEC death, thereby ameliorating I/R-induced renal injury.

In summary, IL-22 treatment ameliorates renal I/R injury, suggesting that IL-22 may have therapeutic potential for the treatment of AKI. Because recombinant IL-22 protein is currently under development for the treatment of acute liver failure, severe forms of liver diseases are often associated with acute tubular necrosis and renal failure caused by intense renal vasoconstriction and subsequent tubular ischemia.9,10 Thus, the protective effect of IL-22 on renal ischemic injury proven here could be the additional benefit of IL-22 treatment in patients with severe liver diseases.

Concise Methods

Materials

Recombinant mouse IL-22 protein was provided by Dr. Xiaoqiang Yan (Generon Corporation).

Animal Models

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The IL-22TG mice were described previously.27 IL-22KO mice on a C57BL/6 background were provided by Dr. Rachel R. Caspi (National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health) with the permission of Dr. Wenjun Ouyang and a signed Material Transfer Agreement from Genentech (San Francisco, CA), and they were further backcrossed to a C57BL/6 background for at least five generations in our facility. Renal I/R was performed in anesthetized (ketamine/xylazine]) male mice (8–12 weeks old) by unilateral clamping of the left renal artery and vein for 40 minutes and then removal of the clamp for reperfusion on a heating pad at 37°C. The vessels of the right kidney were ligated with sutures, and the kidney was subsequently removed. The flank incisions were closed in two layers by silk suture in the body wall and clips in the skin. For the IL-22 treatment group, 30 minutes before I/R, mice received intraperitoneal injection of recombinant mice IL-22 protein (1 mg/kg) or alternatively, saline as control. All animal experiments were approved by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Animal Care and Use Committee.

Histopathology

Paraffin sections (4 µm) from kidneys were dewaxed and stained with PAS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Histologic changes were evaluated by assessment of the extent of cast formation, tubular dilation, and tubular degeneration in the cortex, outer medulla, and inner medulla scored according to the following criteria as described previously28: 0, normal; 1, below 30% of the pertinent area; 2, 30%–70% of the pertinent area; 3, over 70% of the pertinent area. Apoptotic cells in sections of mouse kidneys were detected by an in situ apoptosis detection (TUNEL) kit (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). Neutrophils were detected by stained with anti-MPO (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). The total numbers of apoptotic bodies and neutrophils per field were counted.

Administration of Ad-IL-22 to Mice

Ad-IL-22 and green fluorescence protein (GFP)-expressing adenovirus (Ad-GFP) were provided by Drs. M. Zhang and J. Kolls (Louisiana State University, New Orleans, LA). Adenovirus was prepared as we described previously.20 Mice were injected intravenously with Ad-IL-22 (2×109 pfu) or Ad-GFP (2×109 pfu) 5 days before renal I/R. Ad-IL-22 injection could increase serum IL-22 to ∼3500 pg/ml.

Plasma Assay

Serum creatinine and urea levels at day 1 of reperfusion in mice were determined by using a colorimetric test (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA). Serum IL-22 and IL-22BP levels were determined by ELISA kits (IL-22; R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN; IL-22BP; MyBioSource, Inc., San Diego, CA). Serum IL-6 and TNFα levels were determined by cytometric bead array (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Immunoblotting

Renal tissues were lysed in RIPA buffer using a tissue homogenizer. Protein extracts were separated on 4%–12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Detection was performed using antibodies: pAkt473, pERK1/2, STAT3, pSTAT3, p-p38, phospho c-Jun N-terminal kinase, cleaved caspase-8, caspase-9, caspase-12, CHOP, peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor α, Bad, Bax, Bcl-xl, Bcl-2, and β-actin from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, MA) and IL-22R1 from Abcam, Inc. (Cambridge, MA).

Real-Time PCR

Total cellular RNA was isolated from the kidneys by using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Inc., Valencia, CA); 1 μg total RNA was reverse-transcribed by random priming and incubation with 200 U moloney murine leukemia virus transcriptase at 37°C for 1 hour. The resulting single-stranded cDNA was then subjected to real-time PCR analyses of IL-6, IL-22R1, MCP-1, IL-1β, TNFα, E-selectin, CXCL2, and ICAM1 gene expressions. The sequences of the primers used are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers for real-time PCR

| Gene Name | Forward Primer (5′ … 3′) | Reverse Primer (5′ … 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | ACCAGAGGAAATTTTCAATAGGC | TGATGCACTTGCAGAAAACA |

| IL-22R1 | GTGGGATCCCTGATGGCTGTCCTGCAG | AGCGAATTCTCGCTCAGACTGCAAGCAT |

| MCP-1 | CCAGCCTACTCATTGGGAT | GGGCCTGCTGTTCACAGTT |

| IL-1β | TCGCTCAGGGTCACAAGAAA | CATCAGAGGCAAGGAGGAAAAC |

| TNFα | AGGGTCTGGGCCATAGAACT | CCACCACGCTCTTCTGTCTAC |

| E-selectin | AGCAGAGTTTCACGTTGCAGG | TGGCGCAGATAAGGCTTCA |

| CXCL2 | AAAATCATCCAAAAGATACTGAACAA | CTTTGGTTCTTCCGTTGAGG |

| ICAM1 | CAATTTCTCATGCCGCACAG | AGCTGGAAGATCGAAAGTCCG |

Statistical Analyses

Data are reported as mean±SEM. Unpaired t test was used for analysis of two groups, and one-way ANOVA was used for analysis for three or more groups followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison test as applicable by the use of Prism 5. P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the intramural program of the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the National Institutes of Health (B.G.) and National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 81270370 (to M.-J.X.).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “All of the Twos, 22—Bingo!,” on pages 866–869.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2013060611/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rutz S, Ouyang W: Regulation of interleukin-10 and interleukin-22 expression in T helper cells. Curr Opin Immunol 23: 605–612, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witte E, Witte K, Warszawska K, Sabat R, Wolk K: Interleukin-22: A cytokine produced by T, NK and NKT cell subsets, with importance in the innate immune defense and tissue protection. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 21: 365–379, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kotenko SV, Izotova LS, Mirochnitchenko OV, Esterova E, Dickensheets H, Donnelly RP, Pestka S: Identification of the functional interleukin-22 (IL-22) receptor complex: The IL-10R2 chain (IL-10Rbeta ) is a common chain of both the IL-10 and IL-22 (IL-10-related T cell-derived inducible factor, IL-TIF) receptor complexes. J Biol Chem 276: 2725–2732, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolk K, Witte E, Witte K, Warszawska K, Sabat R: Biology of interleukin-22. Semin Immunopathol 32: 17–31, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mühl H, Scheiermann P, Bachmann M, Härdle L, Heinrichs A, Pfeilschifter J: IL-22 in tissue-protective therapy. Br J Pharmacol 169: 761–771, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonventre JV, Yang L: Cellular pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest 121: 4210–4221, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lameire N, Van Biesen W, Vanholder R: The changing epidemiology of acute renal failure. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 2: 364–377, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM: Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 844–861, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Tsao G, Parikh CR, Viola A: Acute kidney injury in cirrhosis. Hepatology 48: 2064–2077, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akriviadis E, Botla R, Briggs W, Han S, Reynolds T, Shakil O: Pentoxifylline improves short-term survival in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 119: 1637–1648, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson KJ, Weinberg JM: Postischemic renal injury due to oxygen radicals. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2: 625–635, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonventre JV, Weinberg JM: Recent advances in the pathophysiology of ischemic acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 2199–2210, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonventre JV, Zuk A: Ischemic acute renal failure: An inflammatory disease? Kidney Int 66: 480–485, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abuelo JG: Normotensive ischemic acute renal failure. N Engl J Med 357: 797–805, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miura M, Fu X, Zhang QW, Remick DG, Fairchild RL: Neutralization of Gro alpha and macrophage inflammatory protein-2 attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Am J Pathol 159: 2137–2145, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singbartl K, Ley K: Protection from ischemia-reperfusion induced severe acute renal failure by blocking E-selectin. Crit Care Med 28: 2507–2514, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Havasi A, Borkan SC: Apoptosis and acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 80: 29–40, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaushal GP, Basnakian AG, Shah SV: Apoptotic pathways in ischemic acute renal failure. Kidney Int 66: 500–506, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kong X, Feng D, Wang H, Hong F, Bertola A, Wang FS, Gao B: Interleukin-22 induces hepatic stellate cell senescence and restricts liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology 56: 1150–1159, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng D, Kong X, Weng H, Park O, Wang H, Dooley S, Gershwin ME, Gao B: Interleukin-22 promotes proliferation of liver stem/progenitor cells in mice and patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology 143: 188–198, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lejeune D, Dumoutier L, Constantinescu S, Kruijer W, Schuringa JJ, Renauld JC: Interleukin-22 (IL-22) activates the JAK/STAT, ERK, JNK, and p38 MAP kinase pathways in a rat hepatoma cell line. Pathways that are shared with and distinct from IL-10. J Biol Chem 277: 33676–33682, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitra A, Raychaudhuri SK, Raychaudhuri SP: IL-22 induced cell proliferation is regulated by PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling cascade. Cytokine 60: 38–42, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chuang PY, He JC: JAK/STAT signaling in renal diseases. Kidney Int 78: 231–234, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang N, Luo M, Li R, Huang Y, Zhang R, Wu Q, Wang F, Li Y, Yu X: Blockage of JAK/STAT signalling attenuates renal ischaemia-reperfusion injury in rat. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 91–100, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ponnusamy M, Pang M, Annamaraju PK, Zhang Z, Gong R, Chin YE, Zhuang S: Transglutaminase-1 protects renal epithelial cells from hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis through activation of STAT3 and AKT signaling pathways. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F1361–F1370, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J, Ouyang C, Chen X, Fu B, Lu Y, Hong Q: Effect of Jak2 kinase inhibition on Stat1 and Stat3 activation and apoptosis of tubular epithelial cells induced by ATP depletion/recovery. J Nephrol 21: 919–923, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park O, Wang H, Weng H, Feigenbaum L, Li H, Yin S, Ki SH, Yoo SH, Dooley S, Wang FS, Young HA, Gao B: In vivo consequences of liver-specific interleukin-22 expression in mice: Implications for human liver disease progression. Hepatology 54: 252–261, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nomura A, Nishikawa K, Yuzawa Y, Okada H, Okada N, Morgan BP, Piddlesden SJ, Nadai M, Hasegawa T, Matsuo S: Tubulointerstitial injury induced in rats by a monoclonal antibody that inhibits function of a membrane inhibitor of complement. J Clin Invest 96: 2348–2356, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]