Abstract

The glomerular basement membrane (GBM) is a specialized extracellular matrix (ECM) compartment within the glomerulus that contains tissue-restricted isoforms of collagen IV and laminin. It is integral to the capillary wall and therefore, functionally linked to glomerular filtration. Although the composition of the GBM has been investigated with global and candidate-based approaches, the relative contributions of glomerular cell types to the production of ECM are not well understood. To characterize specific cellular contributions to the GBM, we used mass spectrometry–based proteomics to analyze ECM isolated from podocytes and glomerular endothelial cells in vitro. These analyses identified cell type–specific differences in ECM composition, indicating distinct contributions to glomerular ECM assembly. Coculture of podocytes and endothelial cells resulted in an altered composition and organization of ECM compared with monoculture ECMs, and electron microscopy revealed basement membrane–like ECM deposition between cocultured cells, suggesting the involvement of cell–cell cross-talk in the production of glomerular ECM. Notably, compared with monoculture ECM proteomes, the coculture ECM proteome better resembled a tissue-derived glomerular ECM dataset, indicating its relevance to GBM in vivo. Protein network analyses revealed a common core of 35 highly connected structural ECM proteins that may be important for glomerular ECM assembly. Overall, these findings show the complexity of the glomerular ECM and suggest that both ECM composition and organization are context-dependent.

The glomerular basement membrane (GBM) is integral to the glomerular capillary wall, and it directly contributes to barrier function.1,2 The ultrastructural appearance of the GBM shows that it is unusually thick (300–350 nm) as a result of two basement membranes fusing during glomerular development.3 This specialized extracellular matrix (ECM) supports two distinct cell types: glomerular endothelial cells (GEnCs) on the inner capillary wall and podocytes, which form a mesh-like covering of the outer surface. However, there is limited understanding about the relative contribution of each cell type to the regulation of ECM synthesis and organization in the GBM.

Some unique ECM isoforms, essential for normal barrier function, characterize the mature glomerulus. For example, collagen IV networks are predominantly comprised of α1 and α2 chains; however, at the capillary loop stage of glomerular development, there is an isoform switch to the expression of the collagen IV α3α4α5 network in the GBM.4,5 This network is thought to provide the tensile strength necessary to withstand filtration forces.5,6 Similar changes in laminin isoforms have been reported, switching from a combination of laminin 111 and 511 to a predominance of laminin 521 in the mature GBM.7 The importance of glomerular ECM composition for normal barrier function is highlighted by human genetic mutations, which result in the absence of the collagen IV α3α4α5 network in Alport syndrome8 and the absence of laminin 521 in Pierson syndrome.9 However, there is a much wider spectrum of inherited and acquired glomerular disease with associated abnormalities in the GBM, which is not explained by defects in collagen IV or laminin.10,11 Therefore, building understanding of ECM composition in an unbiased manner could help to identify additional genetic defects and appreciate mechanisms of ECM regulation in the glomerulus.

These questions can be initially addressed with studies in vitro, because cell-based investigations allow the dissection of molecular pathways in a manner not feasible in animal studies. Conditionally immortalized human glomerular cells have been derived to facilitate these investigations12,13; however, their ability to synthesize and organize ECM has not been fully investigated. In vivo, these cells are highly specialized, and ex vivo, they may lose critical paracrine and environmental cues required to maintain a differentiated state.14 To test this hypothesis and inform mechanisms of ECM regulation in the glomerulus, global investigation of cell-derived ECM represents a powerful, unbiased analytical approach.

Using an ECM enrichment strategy coupled to mass spectrometry (MS)–based proteomics, we recently described a glomerular ECM proteome derived from isolated human glomeruli.15 To extend this global analysis, we analyzed cell-derived ECM from GEnCs and podocytes to determine their relative contribution to ECM production and regulation in the glomerulus.

Results

Human Glomerular Cells Synthesize and Organize ECM In Vitro

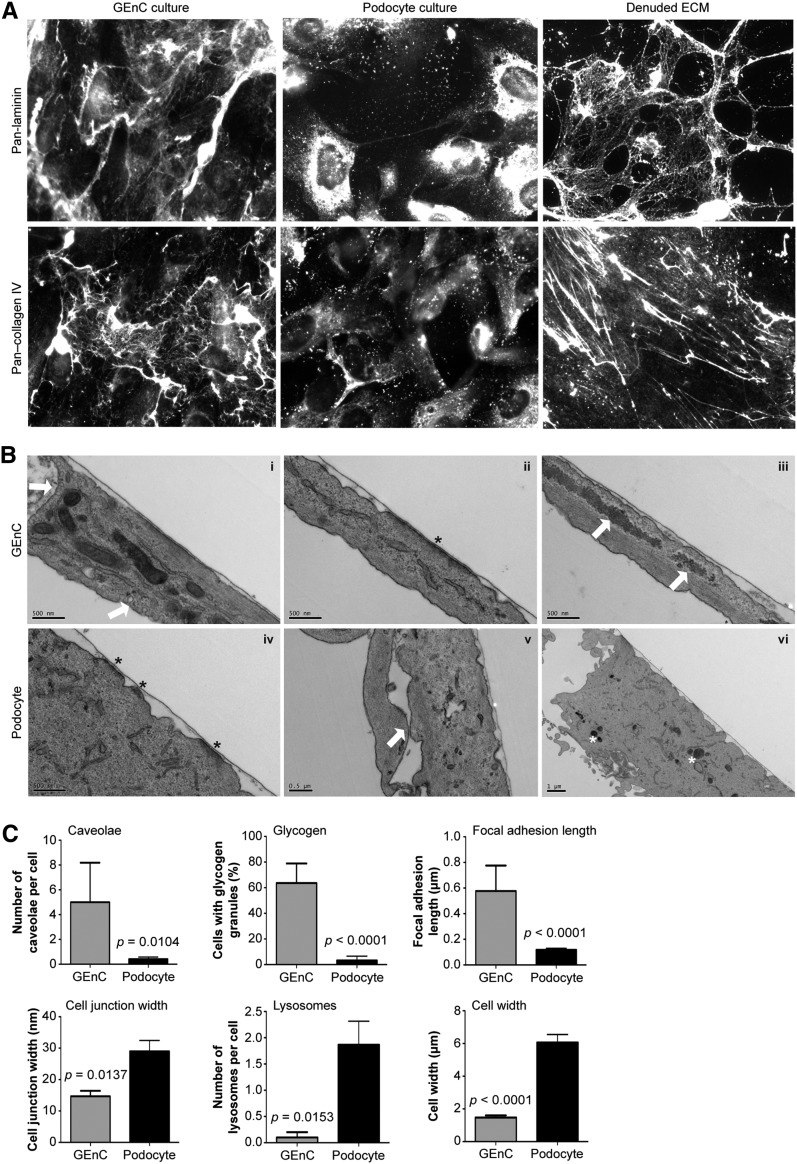

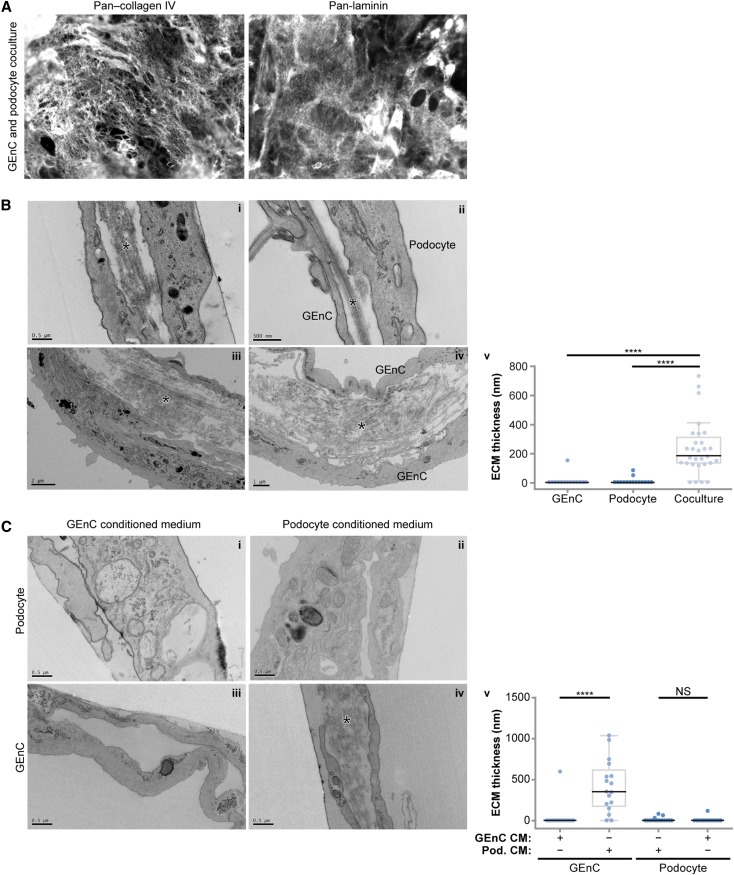

To investigate ECM production by glomerular cells on either side of the GBM, we prepared monocultures of human GEnCs and podocytes in vitro. Both cell types synthesized and deposited ECM (Figure 1A), and this process did not seem disrupted by the removal of cells before ECM extraction (Figure 1A, right panels). Ultrastructural analysis of both glomerular cell types revealed a thin basal layer of ECM (Figure 1B). In addition, GEnCs and podocytes exhibited distinct morphology (Figure 1, B and C). GEnCs had more caveolae, which were visible as small (50- to 100-nm diameter) invaginations of the plasma membrane (Figure 1B, i) and are known to be particularly abundant in endothelial cells.16 GEnCs also had longer focal adhesions, observed as electron-dense sites of cell contact with the ECM (Figure 1B, ii) as well as more glycogen granules (Figure 1B, iii). In contrast, podocytes had wider cell–cell junctions (29±3.4 nm) (Figure 1B, v), more lysosomes (Figure 1B, vi), and greater cell width (6.1±0.49 μm) (Figure 1, B and C).

Figure 1.

Glomerular cells synthesize and organize ECM in vitro. (A) Immunocytochemistry of human GEnC and podocytes showed expression of laminin and collagen IV in vitro. These ECM proteins remained detectable after removal of either cell type (denuded ECM; right panel). (B) Ultrastructural analysis of GEnCs and podocytes revealed morphologic differences. GEnCs had more caveolae (arrows; i) and glycogen deposits (arrows; iii), whereas podocytes had smaller focal adhesions (asterisks; compare ii with iv), wider cell junctions (arrow; v), more lysosomes (asterisks; vi), and greater cell width. Both cell types deposited a thin basal layer of ECM adjacent to focal adhesions. (C) Quantification of morphologic differences between GEnCs (n=11) and podocytes (n=31). Graphs display mean±SEM and results of statistical analysis using unpaired t tests.

Glomerular Cells In Vitro Exhibit Differential ECM Protein Synthesis

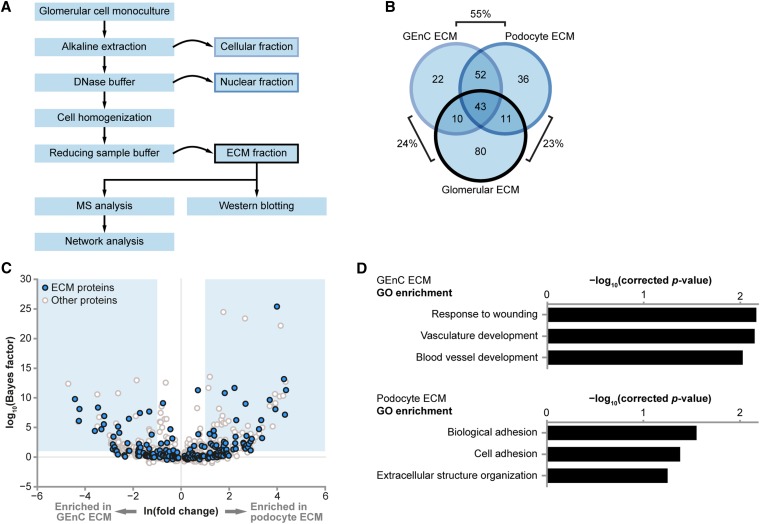

To collect ECM proteins for proteomic analysis, a fractionation workflow was adapted from previous studies (Figure 2A).17,18 Cell-derived ECMs were extracted from both GEnC and podocyte monocultures and analyzed by MS. We identified 127 extracellular proteins in GEnC samples (Supplemental Table 1) and 142 extracellular proteins in podocyte samples (Supplemental Table 2). There was considerable (55%) overlap between proteins detected in GEnC and podocyte ECMs, suggesting a common core of ECM proteins, but cell type–specific proteins were also identified (Figure 2B). Furthermore, 44% of proteins in the recently described in vivo glomerular ECM proteome15 were identified in cell-derived ECMs (Figure 2B). Statistical analysis of all identified proteins in the cell-derived ECM samples revealed differential ECM protein synthesis between GEnCs and podocytes (Figure 2C, Supplemental Table 3). Although gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis highlighted significantly enriched GO terms associated with ECM proteins for both GEnC and podocyte samples (Supplemental Table 4), there was also evidence of cell type–specific differences between the ECMs. Specifically, there was significant enrichment of vascular development processes in GEnC ECM, whereas cell adhesion processes were enriched in podocyte ECM (Figure 2D, Supplemental Table 4). These data indicate a functional distinction between GEnC and podocyte ECMs. Moreover, the expected association of GEnC with endothelial cellular functions suggests that this analysis has the capability to identify proteins with tissue-specific functions.

Figure 2.

GEnCs and podocytes in vitro have differential ECM composition. (A) A proteomic workflow for the isolation of ECM from glomerular cells in vitro. (B) Cell-derived ECM fractions were prepared from human GEnCs (n=3) and human podocytes (n=3) and analyzed by MS. The Venn diagram compares identified ECM proteins with a glomerular ECM dataset, which was derived from isolated human glomeruli. Percentage overlaps of set pairs are indicated. (C) QSpec statistical analysis of all GEnC and podocyte proteins identified by MS shows the differential relative abundance of ECM proteins between datasets. Blue boxes indicate zones of significant differential relative abundance (false discovery rate<5%). (D) GO enrichment analysis of GEnC and podocyte datasets revealed enrichment of distinct biologic process terms. The top three biologic processes for each cell type are shown.

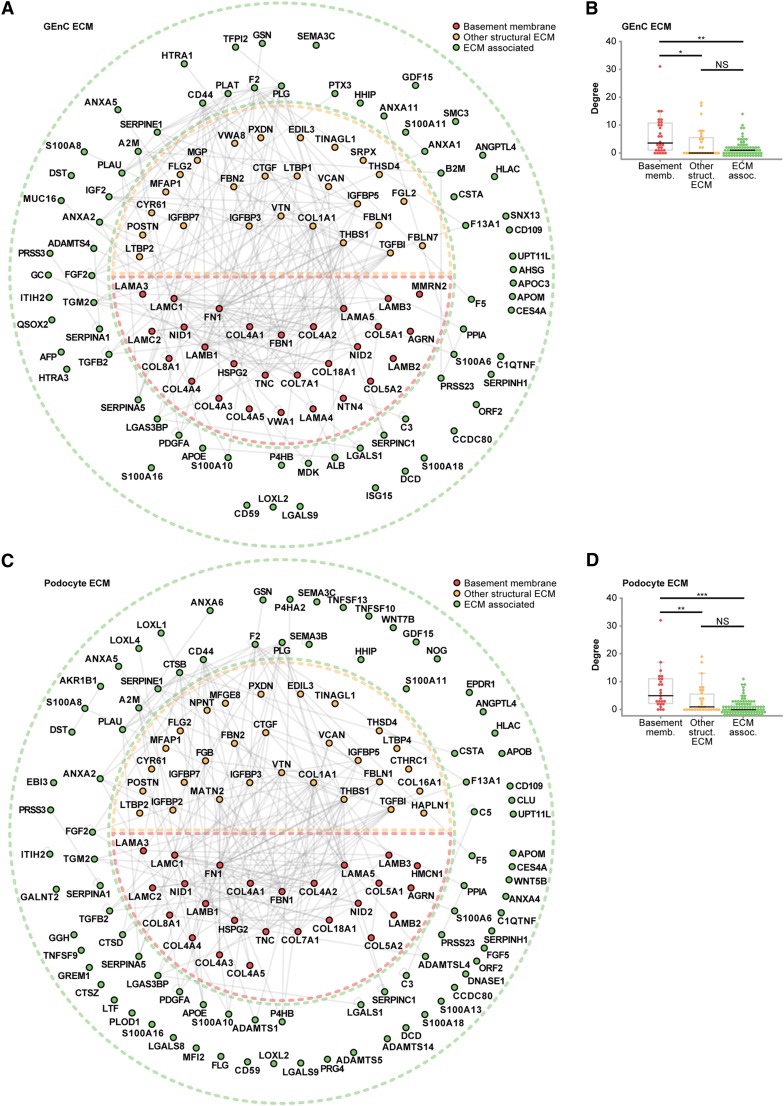

In contrast to the compositional differences highlighted by the GO analysis, previously identified glomerular ECM components were detected to a similar extent in ECMs from both cell types (Figure 2B), suggesting that the ECMs are qualitatively closely related. To examine putative interactions between the identified ECM proteins, interaction networks were generated from a curated protein interaction database (Supplemental Material). ECM protein interaction networks had similar topologies, with highly connected subnetworks of basement membrane and other structural ECM proteins (Figure 3, Supplemental Figures 1 and 2). Highly connected proteins tend to be involved in important biologic functions. Interestingly, basement membrane proteins had a higher number of protein–protein interactions than ECM-associated proteins, suggesting that these molecules play key roles in glomerular ECM organization (Figure 3, B and D). These findings are very similar to the tissue-derived glomerular ECM interactome, which identified a core of highly connected structural components.15 Overall, these data suggest that qualitative differences between GEnC and podocyte ECMs do not affect the core organization of the ECM.

Figure 3.

GEnC and podocytes have distinct ECM interaction networks. (A and C) Protein interaction networks constructed from (A) GEnC or (C) podocyte ECM proteins identified by MS. ECM proteins were classified as basement membrane, other structural ECM, or ECM-associated proteins, and they were colored and arranged accordingly. Nodes are labeled with gene names, and relative node positions are preserved in both interaction networks. (B and D) Distributions of degree (number of protein–protein interactions per protein) for basement membrane, other structural ECM, or ECM-associated proteins for the (B) GEnC or (D) podocyte ECM interaction networks. Data points are shown as circles; outliers are shown as diamonds. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; NS, P≥0.05.

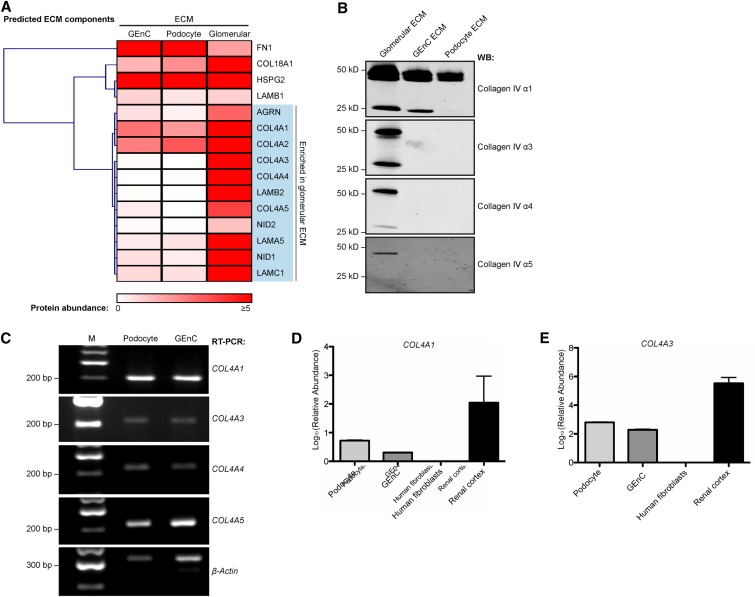

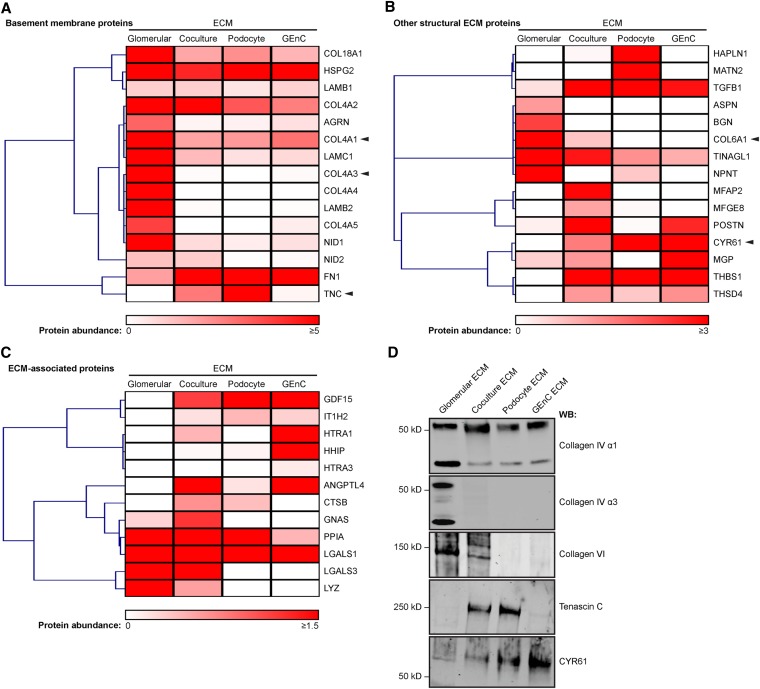

Glomerular Cell–Derived ECM Resembles a Developmental Phenotype

To assess quantitative differences between the compositions of the ECMs, predicted GBM components were analyzed by unsupervised hierarchical clustering. A striking enrichment of collagen IV chains was identified in glomerular ECM compared with cell-derived ECMs (Figure 4A). We found chains of both isoforms in glomerular ECM,15 with a predominance of α1 and α2 chains, which may reflect the mesangial ECM contribution.19 In cell-derived ECMs, we identified α1 and α2 chains by MS, but there was minimal detection of α3, α4, or α5 chains (Figure 4A, Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). These data were confirmed by Western blotting of ECM samples (Figure 4B). Taken together, these findings suggest that ECM derived from glomerular cells in culture resembles a developmental ECM,20 and this concept is further supported by the low relative abundance of laminin β2, a predominant isoform in the mature glomerulus (Figure 4A). Although RT-PCR analysis revealed that both glomerular cell types expressed mRNA for COL4A1, COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5 (Figure 4C), quantitative PCR showed that the relative abundance of mRNA was significantly less than the amount isolated from human renal cortex (Figure 4, D and E). It is conceivable that glomerular cells have the capacity to synthesize both the collagen IV α1α2α1 chains and the mature α3α4α5 chains but require the appropriate environmental context.

Figure 4.

Glomerular ECM in vitro resembles a developmental phenotype. (A) Hierarchical clustering analysis of the abundance of basement membrane proteins identified in GEnC, podocytes, and glomerular ECMs identified a cluster of proteins with increased relative abundance in glomerular ECM. The heat map displays relative protein abundance (normalized spectral count), and the associated dendrogram displays clustering on the basis of uncentered Pearson correlation. Proteins are labeled with gene names for clarity. (B) The low abundance of collagen IV α3, α4, and α5 in GEnC and podocyte ECMs was confirmed by Western blotting (WB) using chain-specific antibodies to detect monomers (approximately 25 kD) and dimers (approximately 50 kD). (C) RT-PCR of RNA pellets from GEnCs and podocytes confirmed expression of COL4A1, COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5 transcripts. M, molecular mass marker. (D and E) Quantitative PCR also confirmed the expression of COL4A1 and COL4A3 in podocytes and GEnCs. The relative mRNA abundance was calculated (Supplemental Material) and compared with mRNA extracted from human fibroblasts and human renal cortex. With the lowest mRNA expression, human fibroblasts were used for normalization, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as the endogenous mRNA control. These data represent n=3 replicates.

Glomerular Cell Coculture Results in Altered ECM Organization

We hypothesized that the developmental phenotype could be caused by a lack of functional interaction between cell types. To investigate the role of cell–cell cross-talk in ECM protein synthesis, GEnCs and podocytes were grown in coculture. Cells were viable in coculture, and over 14 days, the proportion of each cell type did not alter significantly (Supplemental Figure 3). Compared with monoculture, we did not observe differences in podocyte or GEnC cell–cell junctions in coculture (Supplemental Figure 4). However, we found that cells synthesized ECM (Figure 5A, Supplemental Figure 4), and ultrastructural analysis revealed a basal layer of ECM (Figure 5B, i), which was previously seen in monoculture (Figure 1B). In addition, ECM was deposited between cells in coculture (Figure 5B, ii–iv), and this organization resembled a basement membrane, with parallel bundles of ECM proteins. Our phenotypic characterization of cells in monoculture (Figure 1, B and C) enabled the identification of ECM between adjacent GEnCs and podocytes as well as adjacent cells of the same type. Quantification of ECM thickness showed significantly more ECM between cells in coculture compared with monoculture (Figure 5B, v). Furthermore, the thickness of the ECM between cocultured cells was in a range comparable with the thickness of the GBM in vivo.21,22 To investigate whether GEnC–podocyte contact or a soluble mediator was required for this basement membrane-like assembly of ECM, we cultured monocultures in conditioned medium from either the same or the other cell type (Figure 5C). Interestingly, ECM was deposited in significant amounts between GEnC monocultures in podocyte-conditioned medium (Figure 5C, iv), and this increase was significant compared with control-conditioned medium (Figure 5C, v). These data suggest that a secreted molecule released by podocytes contributes to the organization of ECM between glomerular cells.

Figure 5.

Glomerular cell coculture is associated with altered ECM organization. (A) GEnCs and podocytes were combined in cell suspension and seeded as cocultures. The ECM proteins collagen IV and laminin were detected by immunocytochemistry. (B) Ultrastructural analysis of cocultured GEnCs and podocytes revealed a striking difference in ECM organization compared with monocultured cells. Cocultured cells deposited basal ECM (i), and unlike monoculture, they deposited ECM between cells, which is indicated by asterisks (i–iv). Based on characterization of monoculture cells, it was not restricted to podocytes adjacent to GEnC (ii) but also evident with adjacent cells of the same type (iv). ECM deposition between cells was quantified by measuring ECM thickness (v). (C) Podocytes cultured in GEnC or controled conditioned medium and GEnCs cultured in control conditioned medium did not exhibit ECM deposition or organization between cells (i–iii); GEnC cultured in podocyte conditioned medium deposited and organized ECM between cells (asterisk; iv). ECM deposition between cells was quantified by measuring ECM thickness (v). Data points are shown as circles (n=15–29). CM, conditioned medium. ****P<0.001; NS, P≥0.05.

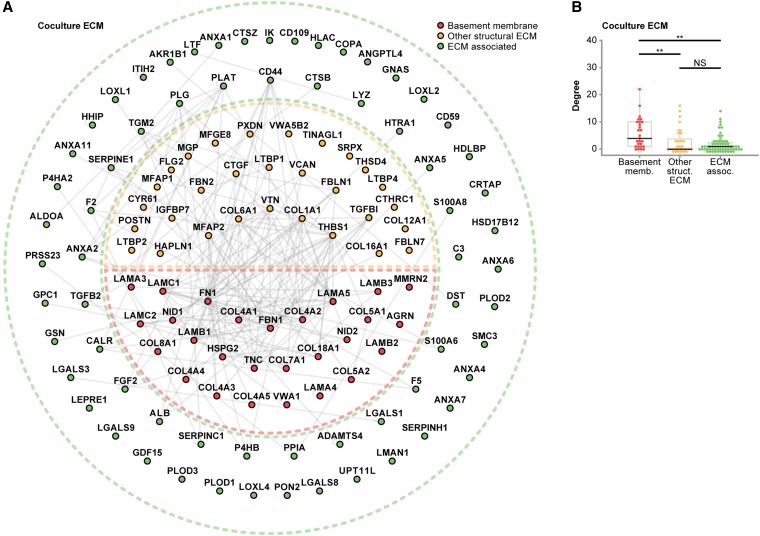

Glomerular Cell Cross-Talk Alters ECM Composition

To capture basal ECM in addition to the ECM deposited between cells, coculture ECM was extracted using a modified glomerular fractionation workflow. Samples were analyzed by MS, which identified 123 extracellular proteins (Supplemental Table 5). Once again, network analysis identified a highly connected subnetwork of basement membrane proteins (Figure 6, Supplemental Figure 4), indicating that the interconnected network topology of core structural components of the glomerular ECM was maintained in coculture. Indeed, basement membrane proteins were similarly identified in coculture and monoculture ECMs (Figure 7A), but more differences were observed in other structural ECM proteins (Figure 7B) and ECM-associated proteins (Figure 7C). We did not observe an increase in the abundance of mature collagen IV chains α3, α4, and α5 in ECM isolated from coculture (Figure 7A), a finding confirmed by Western blotting (Figure 7D). However, collagen VI, which was abundant in tissue-derived glomerular ECM15 and absent in monoculture ECM, was enriched in coculture ECM (Figure 7, B and D). In contrast, tenascin C, which was abundant in podocyte ECM, was less abundant in coculture and absent in glomerular ECM (Figure 7, A and D), and CYR61, an inducer of angiogenesis,23 was most abundant in GEnC ECM but less abundant in coculture and glomerular ECMs (Figure 7, B and D). In summary, glomerular cell coculture results in altered ECM organization and composition compared with monoculture, regulating the synthesis and incorporation of ECM molecules in both a positive (collagen VI) and negative (tenascin C and CYR61) manner.

Figure 6.

Coculture alters ECM composition. (A) Protein interaction network constructed from coculture ECM proteins identified by MS. ECM proteins were classified as basement membrane, other structural ECM, or ECM-associated proteins, and they were colored and arranged accordingly. Nodes are labeled with gene names. (B) Distributions of degree (number of protein–protein interactions per protein) for basement membrane, other structural ECM, or ECM-associated proteins for the coculture ECM interaction network. Data points are shown as circles; outliers are shown as diamonds. **P<0.01; NS, P≥0.05.

Figure 7.

The composition of coculture ECM resembles glomerular ECM in vivo. (A–C) Hierarchical clustering analysis of the abundance of (A) basement membrane proteins, (B) other structural ECM proteins, and (C) ECM-associated proteins identified in glomerular, coculture, podocyte, and GEnC ECMs. Heat maps display relative protein abundance (normalized spectral count), and associated dendrograms display clustering on the basis of uncentered Pearson correlation. Proteins are labeled with gene names for clarity. Arrowheads indicate candidates selected for Western blotting (WB) analysis. (D) WB confirmed the expression of selected structural ECM components identified by MS.

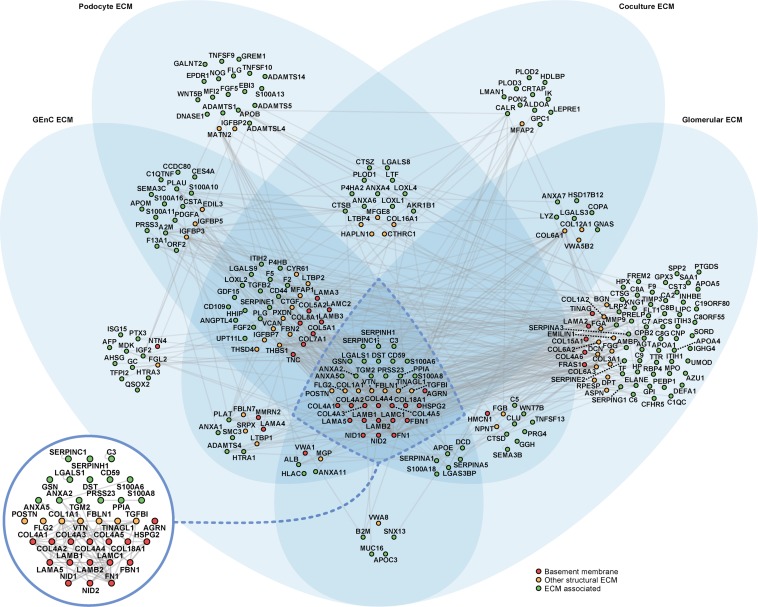

Building the Glomerular ECM Interactome

To investigate the molecular architecture of glomerular ECM in vivo and in vitro, a protein interaction network was generated to compare the monoculture and coculture ECM proteomes and the tissue-derived glomerular ECM proteome.15 In total, 232 proteins were mapped to the interactome, which involved 511 reported protein–protein interactions (Figure 8). By clustering proteins according to their detection in different ECMs, we identified a core subnetwork of 35 proteins detected in cell- and tissue-derived ECM datasets. Intriguingly, these 35 proteins, which represented 15% of proteins in the network, were involved in 259 protein–protein interactions, which represented 51% of interactions in the network, showing a substantial clustering of network connectivity in the core subnetwork (Figure 8). Furthermore, the majority of proteins with the most protein–protein interactions in each ECM network was identified in all four ECM datasets, highlighting that nearly all of the most connected proteins were present in the core subnetwork (Supplemental Figure 5). These findings suggest that these core proteins play key roles in mediating the majority of structural and functional interactions in glomerular ECM in vitro and in vivo. Interestingly, the core ECM components included 50% of the basement membrane proteins (compared with 9% of the ECM-associated proteins) in the interactome, supporting the central role of these structural components in ECM organization. All other basement membrane proteins (apart from von Willebrand factor A domain-containing 1) were detected either in cell-derived ECM or tissue-derived glomerular ECM but not both, suggesting distinct structural ECM subnetworks in vitro and in vivo, which may reflect environmental context-dependent synthesis of glomerular ECM.

Figure 8.

Glomerular ECM networks share a common core of proteins. All three in vitro ECM MS datasets and the in vivo glomerular ECM MS dataset were combined and mapped onto a database of human protein–protein interactions to create an interaction network model. The network comprised 232 glomerular ECM proteins (nodes; circles) and 511 protein–protein interactions (edges; gray lines). Proteins were clustered according to their identification in one or more ECMs; the Venn diagram sets indicate the ECMs in which each protein was identified. A core subnetwork of 35 proteins, which was detected in all four glomerular ECM preparations (central intersection set; inset), was involved in 51% (259) of protein–protein interactions in the network. ECM proteins were categorized as basement membrane, other structural ECM, or ECM-associated proteins, and they were colored accordingly. Nodes are labeled with gene names for clarity.

Discussion

To investigate the relative cellular contribution to glomerular ECM synthesis, we focused on the cells on either side of the GBM and characterized the ECM proteomes of GEnCs and podocytes in vitro. We found that (1) both GEnCs and podocytes synthesized and organized ECM in culture, the composition of which overlapped considerably with the tissue-derived glomerular ECM proteome; (2) the cell-derived ECMs contained distinct components, with the enrichment of proteins involved in vascular development in GEnC ECM and cell adhesion in podocyte ECM; (3) cell-derived ECM resembles a developmental phenotype; (4) glomerular cell cross-talk affects the composition of glomerular ECM; and (5) a core subnetwork of structural ECM proteins seems central to glomerular ECM assembly.

In addition to considerable overlap of ECM components, MS analysis of cell-derived ECMs revealed the enrichment of proteins involved in distinct cellular roles: vascular development in GEnC ECM and cell adhesion in podocyte ECM. This enrichment of cell type-appropriate biologic processes shows that the analysis of ECM isolated in vitro is a suitable approach for the investigation of the relative contribution of different cell types to glomerular ECM assembly.

There is growing evidence that cellular cross-talk within the glomerulus is critical for function.24,25 GEnC and podocyte coculture was used to determine whether cross-talk altered the composition and organization of cell-derived ECM. Ultrastructural analysis revealed the production of ECM between adjacent cells, which had a striking resemblance to a basement membrane. In addition, we observed ECM between GEnCs in monoculture when these cells were cultured in medium conditioned by podocytes. Both observations provide evidence that the assembly and organization of ECM require cross-talk between glomerular cells and suggest that soluble mediators (e.g., growth factors or ECM components) released by podocytes contribute to this effect.

The use of a coculture approach in vitro and hierarchical clustering analysis of MS data identified patterns of protein enrichment in common between the proteomes of the coculture ECM and the tissue-derived glomerular ECM.15 Many of these similarities did not extend to monoculture-derived ECMs, suggesting that cross-talk between GEnCs and podocytes provides cues necessary to generate ECM that better resembles glomerular ECM in vivo. For example, components, such as collagen VI and TINAGL1, were enriched in coculture and glomerular ECM, whereas the expression of other components was reduced compared with monoculture ECM. Interestingly, proteins associated with vascular development, such as CYR6123 and HRTA1,26 were downregulated in coculture ECM compared with GEnC ECM. This finding suggests that paracrine factors may influence cell differentiation and fate. Tenascin C, which was highly expressed in podocyte ECM, was downregulated in coculture ECM and absent in glomerular ECM. This ECM ligand has roles in neurite guidance,27 vascular morphogenesis, and response to wounding.28 The biologic relevance of these molecules for glomerular function has yet to be established; however, our in vitro data suggest that these molecules could have temporally restricted expression in the glomerular ECM.

Among the basement membrane proteins detected, collagen IV chains α3, α4, and α5 and laminin β2 were present in low abundance in cell culture, indicating that cell-derived ECM resembles a developmental ECM phenotype. The expression of these ECM molecules was not substantially altered between monoculture and coculture, which contrasted strongly with the enrichment of these proteins to tissue-derived glomerular ECM.15 Therefore, cell cross-talk between GEnCs and podocytes was not sufficient to recapitulate expression of the mature isoforms of these ECM molecules. We speculate that the developmental ECM phenotype could be caused by the absence of environmental cues, such as flow, tension, or specific cell–cell cross-talk, in our existing cell culture system. Additional investigation and incorporation of these environmental stimuli could lead to improved cell culture systems.

This unbiased global investigation shows the complexity of the glomerular ECM proteome. Using a combination of strategies in vitro, we were able to provide insight into the relative contribution of glomerular cells to ECM production and show that it may be regulated by cell–cell cross-talk. Network analyses revealed distinct and overlapping subnetworks of ECM proteins and a core set of components that may play key roles in the structure and function of glomerular ECM. These networks can now be extended to investigate ECM composition, organization, and regulation in the context of glomerular development and disease.

Concise Methods

Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies used were against β-catenin (610154; BD Biosciences), cleaved caspase-3 (9664; Cell Signaling Technology), PECAM1 (89C2; Cell Signaling), TINAGL1 (ab69036; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), tenascin C (ab108930; Abcam), and collagen IV chains (provided by B. Hudson, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN). Polyclonal antibodies used were against pan-collagen VI (ab6588; Abcam), CYR61 (ab24448; Abcam), and ZO1 (5406; Cell Signaling Technology). Secondary antibodies against rabbit IgG conjugated to tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate and mouse or rat IgG conjugated to FITC (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) were used for immunofluorescence; secondary antibodies conjugated to AlexaFluor 680 (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) or IRDye 800 (Rockland Immunochemicals, Glibertsville, PA) were used for Western blotting.

Glomerular Cell Culture

Conditionally immortalized human podocytes12 and GEnCs13 were grown in monoculture or coculture on uncoated tissue culture plates. Podocytes between passages 10 and 16 were cultured for 14 days at 37°C in RPMI-1640 medium with glutamine (R-8758; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FCS (Life Technologies) and 5% (vol/vol) insulin, transferrin, and selenium (1 ml/100 ml; I-1184; Sigma-Aldrich). GEnCs were grown in endothelial basal medium-2 (CC-3156; Lonza, Slough, UK) containing 5% (vol/vol) FCS and EGM-2 BulletKit growth factors (CC-4147; Lonza), excluding vascular endothelial growth factor, for 5 days at 37°C. For coculture, proliferating cells in suspension were combined, seeded, and cultured in GEnC medium for 14 days at 37°C. For experiments with conditioned medium, feeder podocytes and GEnCs were grown in GEnC medium (as above) for 12 days. Test podocytes and GEnCs were grown in parallel at 37°C for 12 days. Every 48 hours, medium from test cells was removed and replaced with 50% (vol/vol) fresh medium and 50% (vol/vol) conditioned medium from feeder cells. Before addition to test cells, conditioned medium was centrifuged at 1600 rpm for 4 minutes to remove cells and cell debris. Generation of green fluorescent protein–expressing podocytes is described in Supplemental Material.

Nonglomerular Cell Culture

Culture methods for human embryonic kidney 293T cells and human foreskin fibroblasts are described in Supplemental Material.

Isolation of Cell-Derived ECM from Monocultures

ECM was isolated as previously described.17,18 In brief, 15-cm plates (Corning BV Life Sciences, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) were seeded with glomerular cells, and culture medium was exchanged alternately daily for fresh medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid to stabilize ECM fibrils. Differentiated cells were washed with cold PBS, and ECM was denuded of cells by lysis with 20 mM NH4OH and 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 in PBS, which was followed by digestion with 10 μg/ml DNase I (Roche) in PBS containing 1 mM calcium and 0.5 mM magnesium. Denuded ECM was scraped into reducing sample buffer and heat denatured at 70°C for 20 minutes. Three biologic replicates were analyzed for podocyte and GEnC monocultures.

Isolation of Cell-Derived ECM from Cocultures

To recover ECM deposited between cocultured cells, the method of ECM enrichment from tissue (described above) was adapted. Differentiated cells were washed with cold PBS. Cells and ECM were scraped into extraction buffer and incubated for 30 minutes, which was followed by centrifugation at 14,000×g for 10 minutes. The resulting pellet was resuspended in alkaline detergent buffer for 5 minutes before centrifuging at 14,000×g for 10 minutes. The pellet was incubated in DNase buffer for 30 minutes and then centrifuged at 14,000×g for 10 minutes before resuspension in reducing sample buffer. Samples were heat denatured at 70°C for 20 minutes. Three coculture biologic replicates were analyzed.

Collagenase Treatment

To release collagen NC1 epitopes for Western blotting, glomerular isolates were initially treated with 500 μg/ml collagenase in PBS (CLSPA grade; Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ) overnight at 37°C. For cell-derived ECM, cells were washed two times in PBS and scraped into cold PBS, which was followed by incubation with collagenase (50 μg/ml) in PBS for 2 hours at 37°C. ECM samples treated with collagenase were not used for MS analysis but prepared in parallel for collagen IV analysis by Western blotting under nonreducing conditions.

Western Blotting and Proteomic Analyses

Western blotting, MS, and proteomic data analyses were performed as described previously,17,29 with modifications as described in Supplemental Material. The MS proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) through the PRoteomics IDEntifications partner repository30 with the dataset identifier PXD000643.

Cellular Immunofluorescence

Cells on coverslips were washed with PBS and then fixed with 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde. Cells were permeabilized with 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 and blocked with 3% (wt/vol) BSA in PBS before incubation with primary antibodies. Coverslips were mounted, and images were collected using a CoolSnap HQ camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) and separate 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole/FITC/Cy3 filters (U-MWU2, 41001, and 41007a, respectively; Chroma, Olching, Germany) to minimize bleedthrough between the different channels. For analysis of cell–cell junctions and three-dimensional ECM models, images were acquired on a Delta Vision (Applied Precision) restoration microscope using a 60× objective and the Sedat filter set (89000; Chroma). The images were collected using a Coolsnap HQ (Photometrics) camera with a Z optical spacing of 0.2 μm. For cell–cell junction images, raw images were deconvolved using the Softworx software, and maximum intensity projections of these deconvolved images are shown in Results. For three-dimensional models of ECM organization, raw image Z stacks were processed using Fiji/ImageJ software. Briefly, acquired Z stacks were segmented, and features were traced using TrakEM2.31 The resulting model was visualized using the three-dimensional viewer plug-in (ImageJ_3D_Viewer.jar).

RT-PCR and Quantitative PCR

Isolation of RNA and RT-PCR analysis are detailed in Supplemental Material.

Transmission Electron Microscopy and ECM Quantification

Samples were fixed for at least 1 hour in a mix of 2% formaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). The samples were postfixed with reduced osmium of 1% OsO4 and 1.5% K4Fe(CN)6 for 1 hour; then, they were postfixed with 1% tannic acid in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 1 hour and finally, 1% uranyl acetate in water overnight. The specimens were dehydrated with alcohols, infiltrated with low viscosity resin (TAAB Laborabories Equipment Ltd, Berkshire, UK), and polymerized for 12 hours at 60°C. Specimens were then detached from the aclar coverslips and glued together with the resin for an additional 24 hours of polymerization. Ultrathin 70-nm sections were cut with a Leica Ultracut S ultramicrotome and placed on formvar/carbon-coated slot grids. The grids were observed in a Tecnai 12 Biotwin transmission electron microscope at 80 kV. Electron microscopy data from three separate experiments were screened for ECM deposition between cells using Fiji/ImageJ software (version 1.46r; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). ECM thicknesses between cells were quantified in three regions per observation and reported as mean values.

Statistical Analyses

All measurements are shown as mean±SEM. Box plots indicate 25th and 75th percentiles (lower and upper bounds, respectively), 1.5× interquartile range (whiskers), and median (black line). Numbers of protein–protein interactions and ECM thicknesses were compared using Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA tests with post hoc Bonferroni correction. GO enrichment analyses were compared using modified Fisher’s exact tests with Benjamini–Hochberg correction. P values<0.05 were deemed significant.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

Mass spectrometry was performed in the Biological Mass Spectrometry Core Facility, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester, and we thank David Knight and Stacey Warwood for advice and technical support. We thank Julian Selley for bioinformatic support. Microscopy was performed in the Bioimaging and Electron Microscopy Core Facilities, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester. The collagen IV chain-specific antibodies were provided by the Billy Hudson research group, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt Medical Center. Human tissue samples were provided the Manchester Biomedical Research Centre Biobank and Manchester Institute of Nephrology and Transplantation Biobanks at the Manchester Royal Infirmary.

R.Z. is supported by Veterans Affairs Merit Awards 1I01BX002196-01, DK075594, DK069221, and DK083187, and an American Heart Association Established Investigator Award. This work was supported by Wellcome Trust Grant 092015 (to M.J.H.), Wellcome Trust Intermediate Fellowship Award 090006 (to R.L.), and a research grant to R.L. from Kids Kidney Research. The mass spectrometer and microscopes used in this study were purchased with grants from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, and the University of Manchester Strategic Fund.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2013070795/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kanwar YS, Linker A, Farquhar MG: Increased permeability of the glomerular basement membrane to ferritin after removal of glycosaminoglycans (heparan sulfate) by enzyme digestion. J Cell Biol 86: 688–693, 1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deen WM: What determines glomerular capillary permeability? J Clin Invest 114: 1412–1414, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrahamson DR, Hudson BG, Stroganova L, Borza DB, St John PL: Cellular origins of type IV collagen networks in developing glomeruli. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1471–1479, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harvey SJ, Zheng K, Sado Y, Naito I, Ninomiya Y, Jacobs RM, Hudson BG, Thorner PS: Role of distinct type IV collagen networks in glomerular development and function. Kidney Int 54: 1857–1866, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalluri R, Shield CF, Todd P, Hudson BG, Neilson EG: Isoform switching of type IV collagen is developmentally arrested in X-linked Alport syndrome leading to increased susceptibility of renal basement membranes to endoproteolysis. J Clin Invest 99: 2470–2478, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gunwar S, Ballester F, Noelken ME, Sado Y, Ninomiya Y, Hudson BG: Glomerular basement membrane. Identification of a novel disulfide-cross-linked network of alpha3, alpha4, and alpha5 chains of type IV collagen and its implications for the pathogenesis of Alport syndrome. J Biol Chem 273: 8767–8775, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noakes PG, Miner JH, Gautam M, Cunningham JM, Sanes JR, Merlie JP: The renal glomerulus of mice lacking s-laminin/laminin beta 2: Nephrosis despite molecular compensation by laminin beta 1. Nat Genet 10: 400–406, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barker DF, Hostikka SL, Zhou J, Chow LT, Oliphant AR, Gerken SC, Gregory MC, Skolnick MH, Atkin CL, Tryggvason K: Identification of mutations in the COL4A5 collagen gene in Alport syndrome. Science 248: 1224–1227, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zenker M, Aigner T, Wendler O, Tralau T, Müntefering H, Fenski R, Pitz S, Schumacher V, Royer-Pokora B, Wühl E, Cochat P, Bouvier R, Kraus C, Mark K, Madlon H, Dötsch J, Rascher W, Maruniak-Chudek I, Lennert T, Neumann LM, Reis A: Human laminin beta2 deficiency causes congenital nephrosis with mesangial sclerosis and distinct eye abnormalities. Hum Mol Genet 13: 2625–2632, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kopp JB: Glomerular homeostasis requires a match between podocyte mass and metabolic load. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1273–1275, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kashtan CE, Segal Y: Genetic disorders of glomerular basement membranes. Nephron Clin Pract 118: c9–c18, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saleem MA, O’Hare MJ, Reiser J, Coward RJ, Inward CD, Farren T, Xing CY, Ni L, Mathieson PW, Mundel P: A conditionally immortalized human podocyte cell line demonstrating nephrin and podocin expression. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 630–638, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satchell SC, Tasman CH, Singh A, Ni L, Geelen J, von Ruhland CJ, O’Hare MJ, Saleem MA, van den Heuvel LP, Mathieson PW: Conditionally immortalized human glomerular endothelial cells expressing fenestrations in response to VEGF. Kidney Int 69: 1633–1640, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chittiprol S, Chen P, Petrovic-Djergovic D, Eichler T, Ransom RF: Marker expression, behaviors, and responses vary in different lines of conditionally immortalized cultured podocytes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 301: F660–F671, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lennon R, Byron A, Humphries JD, Randles MJ, Carisey A, Murphy S, Knight D, Brenchley PE, Zent R, Humphries MJ: Global analysis reveals the complexity of the human glomerular extracellular matrix. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 939–951, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank PG, Woodman SE, Park DS, Lisanti MP: Caveolin, caveolae, and endothelial cell function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23: 1161–1168, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rashid ST, Humphries JD, Byron A, Dhar A, Askari JA, Selley JN, Knight D, Goldin RD, Thursz M, Humphries MJ: Proteomic analysis of extracellular matrix from the hepatic stellate cell line LX-2 identifies CYR61 and Wnt-5a as novel constituents of fibrotic liver. J Proteome Res 11: 4052–4064, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soteriou D, Iskender B, Byron A, Humphries JD, Borg-Bartolo S, Haddock MC, Baxter MA, Knight D, Humphries MJ, Kimber SJ: Comparative proteomic analysis of supportive and unsupportive extracellular matrix substrates for human embryonic stem cell maintenance. J Biol Chem 288: 18716–18731, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heidet L, Cai Y, Guicharnaud L, Antignac C, Gubler MC: Glomerular expression of type IV collagen chains in normal and X-linked Alport syndrome kidneys. Am J Pathol 156: 1901–1910, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miner JH: Building the glomerulus: A matricentric view. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 857–861, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanwar YS, Farquhar MG: Presence of heparan sulfate in the glomerular basement membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76: 1303–1307, 1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogawa S, Ota Z, Shikata K, Hironaka K, Hayashi Y, Ota K, Kushiro M, Miyatake N, Kishimoto N, Makino H: High-resolution ultrastructural comparison of renal glomerular and tubular basement membranes. Am J Nephrol 19: 686–693, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Babic AM, Kireeva ML, Kolesnikova TV, Lau LF: CYR61, a product of a growth factor-inducible immediate early gene, promotes angiogenesis and tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95: 6355–6360, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eremina V, Sood M, Haigh J, Nagy A, Lajoie G, Ferrara N, Gerber HP, Kikkawa Y, Miner JH, Quaggin SE: Glomerular-specific alterations of VEGF-A expression lead to distinct congenital and acquired renal diseases. J Clin Invest 111: 707–716, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan S, Lakhe-Reddy S, McCarty JH, Sorenson CM, Sheibani N, Reichardt LF, Kim JH, Wang B, Sedor JR, Schelling JR: Mesangial cell integrin αvβ8 provides glomerular endothelial cell cytoprotection by sequestering TGF-β and regulating PECAM-1. Am J Pathol 178: 609–620, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang L, Lim SL, Du H, Zhang M, Kozak I, Hannum G, Wang X, Ouyang H, Hughes G, Zhao L, Zhu X, Lee C, Su Z, Zhou X, Shaw R, Geum D, Wei X, Zhu J, Ideker T, Oka C, Wang N, Yang Z, Shaw PX, Zhang K: High temperature requirement factor A1 (HTRA1) gene regulates angiogenesis through transforming growth factor-β family member growth differentiation factor 6. J Biol Chem 287: 1520–1526, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meiners S, Mercado ML, Nur-e-Kamal MS, Geller HM: Tenascin-C contains domains that independently regulate neurite outgrowth and neurite guidance. J Neurosci 19: 8443–8453, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Obberghen-Schilling E, Tucker RP, Saupe F, Gasser I, Cseh B, Orend G: Fibronectin and tenascin-C: Accomplices in vascular morphogenesis during development and tumor growth. Int J Dev Biol 55: 511–525, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Humphries JD, Byron A, Bass MD, Craig SE, Pinney JW, Knight D, Humphries MJ: Proteomic analysis of integrin-associated complexes identifies RCC2 as a dual regulator of Rac1 and Arf6. Sci Signal 2: ra51, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vizcaíno JA, Côté RG, Csordas A, Dianes JA, Fabregat A, Foster JM, Griss J, Alpi E, Birim M, Contell J, O’Kelly G, Schoenegger A, Ovelleiro D, Pérez-Riverol Y, Reisinger F, Ríos D, Wang R, Hermjakob H: The PRoteomics IDEntifications (PRIDE) database and associated tools: Status in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res 41[Database Issue]: D1063–D1069, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cardona A, Saalfeld S, Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Preibisch S, Longair M, Tomancak P, Hartenstein V, Douglas RJ: TrakEM2 software for neural circuit reconstruction. PLoS One 7: e38011, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]