Abstract

Bone metastases are a clinically significant problem that arises in approximately 70% of metastatic breast cancer patients. Once established in bone, tumor cells induce changes in the bone microenvironment that lead to bone destruction, pain, and significant morbidity. While much is known about the later stages of bone disease, less is known about the earlier stages or the changes in protein expression in the tumor micro-environment. Due to promising results of combining magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Imaging Mass Spectrometry (MALDI IMS) ion images in the brain, we developed methods for applying these modalities to models of tumor-induced bone disease in order to better understand the changes in protein expression that occur within the tumor-bone microenvironment. Specifically, we integrated three dimensional-volume reconstructions of spatially resolved MALDI IMS with high-resolution anatomical and diffusion weighted MRI data and histology in an intratibial model of breast tumor-induced bone disease. This approach enables us to analyze proteomic profiles from MALDI IMS data with corresponding in vivo imaging and ex vivo histology data. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time these three modalities have been rigorously registered in the bone. The MALDI mass-to-charge ratio peaks indicate differential expression of calcyclin, ubiquitin, and other proteins within the tumor cells, while peaks corresponding to hemoglobin A and calgranulin A provided molecular information that aided in the identification of areas rich in red and white blood cells, respectively. This multimodality approach will allow us to comprehensively understand the bone-tumor microenvironment and thus may allow us to better develop and test approaches for inhibiting bone metastases.

Keywords: MALDI, MRI, metastases, bone, image co-registration

Introduction

Prostate, breast, renal, lung and thyroid cancers frequently metastasize to bone where they can induce changes in the normal remodeling processes, resulting in pain and fractures. Over the past 25 years the vicious cycle model in which tumor cells secrete factors that stimulate bone destruction and the release of growth factors from the bone, which in turn stimulate tumor cell growth and further bone destruction, has become well-accepted [1]. Based on this model, we understand that tumor cells interact with the bone microenvironment to enhance osteolysis [2]. However, quantitative techniques have not been available to rigorously test the hypotheses generated by the vicious cycle. In particular, the lack of techniques to simultaneously assess changes in protein expression in multiple tissues of the tumor microenvironment while also assessing changes in the bone and tumor has restricted our understanding of the tumor microenvironment. Additionally, no single modality can address the complexity of tumor-induced bone disease. As new techniques in biomedical imaging science and proteomics have evolved that allow for higher spatial resolution and the ability to co-register multiple modalities, it is now possible to fuse quantitative in vivo imaging data with ex vivo protein profiling, opening the possibility to explore changes in protein expression within the bone microenvironment.

Over the past two decades, in vivo studies of murine models of cancer-induced bone disease have relied heavily upon histomorphometry and x-ray radiography. However, radiography lacks the ability to report specifically on cellular or molecular events, and histological analyses are limited to end-point ex vivo analyses. The aim of this study was to determine if we could use state-of-the-art imaging techniques to better understand and detect the molecular processes that occur at the tumor-bone interface during the progression of tumor-induced bone disease. In order to do this, we developed a method whereby magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Imaging Mass Spectrometry (MALDI IMS) techniques can be spatially co-registered in a murine tumor-bone model.

In this study, we focus on linking the MALDI IMS data to diffusion weighted MRI, a readout of the self-diffusion (i.e., Brownian motion) of water, which is the microscopic thermally-induced behavior of molecules moving in a random pattern. The rate of water diffusion in tissues is lower than in free solution and is described by an apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), which largely depends on the number, permeability and separation of barriers that a diffusing water molecule encounters. MRI methods have been developed to map the ADC of tissues, and in well-controlled situations the variations in ADC have been shown to correlate inversely with tissue cellularity [3]. Studies in both humans and small animals have indicated that ADC values can distinguish between normal, benign, and malignant tissues, as well as monitor and even predict tumor response to therapy [4]. The ability to link parametric maps of the ADC of tissues with MALDI IMS and histological sections may provide further insights into the mechanisms that result in differential ADC values.

MALDI IMS is unique in its ability to provide a wealth of semi-quantitative information about hundreds of proteins without prior knowledge of the analytes or extensive sample preparation [5–7]. The ability to analyze proteins directly from the tissue section preserves the spatial localization within the tissue that is lost with other proteomic technologies that require tissue homogenization such as 2D gel electrophoresis or shot-gun proteomics. Mass spectrometers are being designed specifically as imaging instruments, which allow for high throughput data acquisition that can be directly correlated with optical and histological images of the tissue section [8]. MALDI imaging technologies are now being applied to a host of clinical samples ranging from cancer [9–13] to infection [14] to Alzheimer’s disease [15] to drug and metabolite analysis [16]. The field has gradually progressed to the analysis of larger samples such as sections of whole animals [17, 18] and to three dimensional reconstruction of small brain structures [19]. We have also begun to correlate these results with other, more traditional modalities such as histology [20] and MRI [21]. Correlation of multiple imaging techniques, including mass spectrometry, facilitates the association of molecular changes with histological and diffusion changes and paints a much more in depth picture of the disease pathology.

Integrating in vivo imaging and ex vivo MALDI IMS was initially accomplished in the rodent brain [21], although co-registration has recently been shown in the mouse kidney of an S. aureus infected animal [22]. The brain provides a number of advantages over other organ sites due to its relatively large size, the presence of internal fiducial markers (white matter, grey matter, etc.) that are readily visible by multiple imaging techniques, its relatively firm composition (compared to other soft tissues), and the presence of a surrounding rigid skull. These characteristics facilitate the registration of multiple imaging modalities. However, in organ sites outside of the brain, many of these key traits are absent, and therefore, the registration of multiple imaging techniques is significantly more difficult, particularly when the registration is performed across multiple spatial scales. In this study, we provide a method to intimately combine MALDI IMS, diffusion MRI, and standard histology stains in a murine model of breast cancer cell growth in bone, reflective of the post-metastatic process. We hypothesized that the combination of these techniques would allow us to more comprehensively understand the interactions between the bone and the tumor microenvironment. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first contribution providing a method to link these three techniques in a metastatic cancer model or within the context of bone.

Methods

Animal Model

For these studies we utilized the previously-established human breast cancer cell line that will grow in bone, MDA-MB-231 [23], and expresses the Green Fluorescent protein [24]. Four week old female athymic nude mice were inoculated with 2×106 GFP-labeled MDA-MB-231 cells in 10 μl of PBS directly into the tibia. As a control, the contra-lateral limb was injected with 10 μl of PBS.

Imaging

Mice were monitored weekly using x-ray analysis, fluorescence imaging (GFP), and MRI. For radiography, anesthetized animals were placed in a prone position on the platform of a Faxitron LX-60 (Faxitron X-Ray LLC, Lincolnshire, IL), and images acquired at 35 KVP for 8 seconds.

For fluorescent imaging of GFP-tagged tumor cells, mice were anesthetized using a 2%/98% isoflurane/oxygen and placed in the MAESTRO™ (CRi, Woburn, MA) imaging unit. The collected images were spectrally unmixed to remove background fluorescence.

Four weeks post-injection, four mice were stabilized as indicated in Figure 1 and imaged by MRI. MRI employed a Varian 7.0 T 16 cm bore MRI/MRS spectrometer equipped with a 25 mm transmit/receive quadrature volume coil. After localization and shimming, two data sets were acquired: 1) high resolution 3D spoiled gradient recalled echo (SPGRE) T1-weighted images for purposes of anatomical landmarks and registration to other modalities; and 2) diffusion weighted spin echo data to construct parametric maps of the ADC for comparison with the proteomic and histological data. The parameters for the 3D SPGRE acquisition were TR\TE\α\nex= 20 ms\2.24 ms\20°\2, with an acquisition matrix of 160×160×8 over a 32 mm × 32 mm × 17.6 mm field of view (FOV). For diffusion MRI, the parameters were: TR\TE\nex = 1000 ms\41.17 ms\1, with an acquisition matrix of 192×192×30 over 32 mm×32 mm×15mm field of view. The diffusion sensitizing gradients were applied along the principal directions with δ\Δ = 5.5 ms\28 ms and gradient strength incremented to yield b-values of 57, 633, and 1106 s2/mm. The diffusion weighted images were used to calculate ADC values for each voxel via Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where S(0) denotes the signal intensity in the absence of diffusion gradients, b reflects the strength and duration of a diffusion-sensitizing gradient, and S(b) is the signal intensity at the nonzero b-value. Immediately after imaging, each animal was sacrificed, perfused with saline and snap frozen with a mixture of hexane and dry ice prior to being embedded in an ice block to minimize any postmortem protein degradation and to allow for rigid sectioning as previously described in Sinha et al [21].

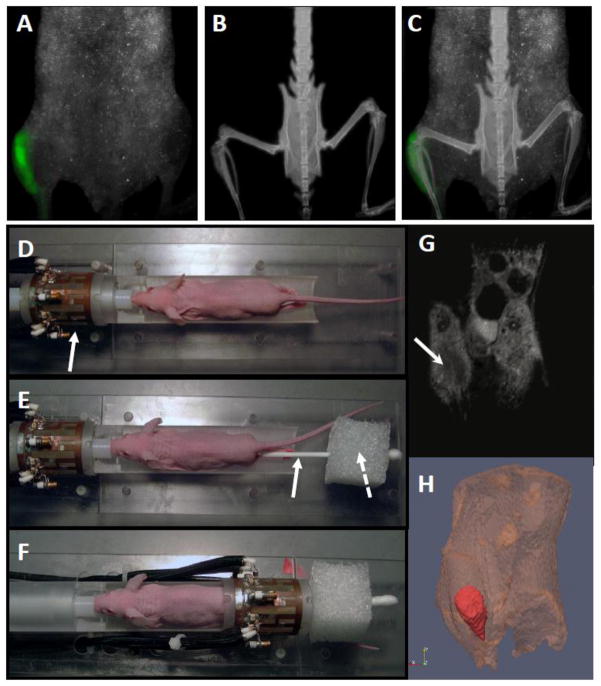

Figure 1. Multimodal imaging of tibial tumor.

Four-week old athymic nude mice were inoculated with MDA-MB-231 cells directly into the tibia and monitored for tumor growth and bone destruction at 3–4 weeks. (A) Tumor cell growth was measured using CRI Maestro for in vivo fluorescence imaging. (B) Tumor-induced bone destruction was monitored using the Faxitron LX-60 X-ray system. (C) Maestro and Faxitron images were aligned by the mouse spinal cord to demonstrate tumor cell fluorescence within the bone. (D) To stablize tumor-bearing limbs for subsequent MRI and tissue proteomic analysis, the anesthetized mouse was placed on a custom built holder within the RF coil (solid arrow). (E) The mouse legs were attached with surgical tape to a long cotton swab (solid arrow) placed through a small (~ 3 cm in each dimension) Styrofoam cube (dashed arrow). (F) The Styrofoam cube holds the cotton swab and mouse legs taut so that when the legs are centered within the coil, they are unlikely to move during the imaging process. (G) ADC images of an MDA-MB-231 cell tumor 3 weeks after injection. The dark region (white arrow) indicates an area of restricted water diffusion (decreased ADC) which correlates with the increased cellularity typical of tumors. (H) 3-dimensional volumetric rendering of tumor from the high resolution 3D MRI data with tumor false-colored in red.

Mass Spectrometry

The frozen tissue was sectioned on a Leica CM3600 cryo-macrotome (Leica Microsystems, Richmond, IL) in the cranial-caudal direction; sections were 15 μm thick. We acquired images of the iceblock-encased specimen every 30 μm using a high-resolution digital camera (Canon EOS 30D SLR, Lake Success, NY) and then reconstructed the images into a continuous volume termed a “blockface” for use in the co-registration process described below.

Tissue sections for MALDI were collected every 300 μm through the tumor region onto indium-tin oxide (ITO) coated glass plates (Delta Technologies, Loveland, CO) using the Instrumedics, Inc. Macro Tape Transfer system (Leica). Each section was collected on a piece of tape and the tape adhered to the surface of an ITO or microscopy slide that had been coated with a thin film of a photoactive polymer. The polymer was crosslinked using a UV light source to bind the section to the surface of the slide. The tape was then removed and discarded. This tape transfer process allowed for high integrity section transfer with minimal sample loss. Serial sections were collected on standard microscope slides for H&E staining using standard protocols. MALDI sections were fixed by sequential submersion in 70%, 90%, and 95% ethanol for 30 seconds each and stored at −80°C until further analysis.

Sinapinic acid matrix (20 mg/mL in 1:1 acetontrile: 0.2% trifluoracetic acid in water) was applied in a regular array with a 200 μm center-to-center spacing using a Portrait 630 acoustic robotic microspotter (Labcyte, Sunnyvale, CA). A total of 30 drops of 170 pL volume were applied to each location in flyby mode in six passes of five drops each. Pictures were taken of each section before and after matrix application using an Epson Scan flatbed scanner (Long Beach, CA) at a resolution of 2400 dpi.

MALDI images were acquired on a Bruker Daltonics AutoFlex II mass spectrometer (Billerica, MA) equipped with a SmartBeam™ (Nd:YAG, 355 nm, 200 Hz) laser. Data were acquired in linear, positive ion mode over the mass range 2–40 kDa using an extraction voltage of 20 kV, an acceleration voltage of 18.65 kV, and delayed extraction parameters optimized for resolution at 12 kDa. Each spectrum was collected as a sum of 200 laser shots acquired in 50 shot increments from 4 different locations within a single matrix spot. Spectra were externally calibrated using a mixture of bovine insulin, equine cytochrome c, equine apomyoglobin, and bovine trypsinogen. Images were set up and viewed using FlexImaging (Bruker) software and exported as Analyze 7.5 (*.img) files for co-registration purposes.

Data Analysis

Raw MALDI imaging datasets consisted of spectra giving the relative intensity of ions recorded at each mass-to-charge ratio over the mass range of data acquisition for each pixel in the imaging field of view (FOV). Baseline correction was performed using the ‘msbackadj’ routine in MATLAB (Natick, Massachusetts, USA). The five largest peaks were used for peak alignment using the ‘msalign’ function. Data were normalized to total ion current.

Individual ion images for visualization were generated by area under the curve calculations for individual spectra, using a selected m/z value +/− 5 Da. The resulting ion images then characterized the relative intensity of the molecule of interest at each location within the FOV. These ion images were ultimately co-registered to the in vivo MR images using the registration technique described below.

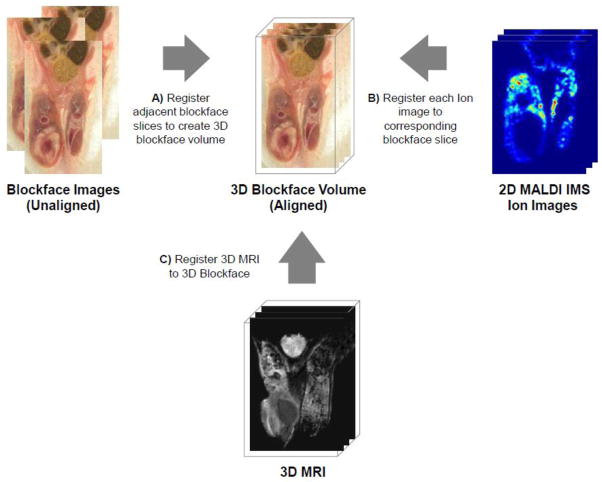

Registration

The co-registration process encompassed a series of transformations that allowed accurate alignment of the in vivo MR images with the ex vivo MALDI datasets. First, the blockface image volume was constructed using an iterative process in which each image of the sliced iceblock was rigidly registered to the previous one working from the medial slice towards the posterior slice, and repeating from the medial slice towards the anterior slice. The blockface volume served as an intermediate digital reference structure to which both the MR and MALDI IMS data could be registered to yield hybrid MR/MALDI IMS datasets with each spatial location sharing measurements from both modalities. Custom MATLAB scripts generated spatially resolved ion images using the pixel coordinates from the mass spectrometry image. Next, the MALDI IMS data ion images were manually co-registered in a rigid fashion to their corresponding blockface image in order to place the data into the coordinate system of the blockface. The final step in generating the hybrid MR/MALDI IMS datasets involved rigidly co-registering the in vivo 3D MRI to the blockface volume. Altogether, the concatenation of these steps provided a complete and continuous transformation of motor coordinates of the MALDI imaging system to the in vivo imaging space of the MR images, generating fused MR/MALDI IMS datasets that could be quantitatively analyzed (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Schematic of the registration process.

(A) Firstly, blockface images are registered to form a 3D image. (B) The 2D MALDI images are registered to the appropriate blockface slices (C) while the 3D MRI is registered to the 3D blockface.

Statistical Classification

Statistical analysis and generation of classification images were carried out using ClinProTools (Bruker). While it has been reported that under controlled conditions, MALDI analysis of tissue sections can be highly reproducible [25, 26], standard statistical methods take any variations into account and allow for determination of proteins that are changed in different histological regions. Using histological sections as a guide, approximately 30 spectra each from regions of tumor, muscle, skin, and bone marrow were selected from the MALDI image data of an animal with a large, necrotic tumor. These spectra were loaded into ClinProTools and subjected to baseline correction, normalization and peak boundaries were manually selected using the average spectra for each class. A Genetic Algorithm classification model was generated using a mutation rate of 0.2, a crossover rate of 0.5, and was allowed to run for 50 generations to determine the optimal set of mass spectral peaks for differentiating the tissue types. A leave-20%-out cross validation was used to determine the effectiveness of the model. In this approach, 20% of the data were randomly selected to be left out and a model generated using the remaining 80% of the data. The 20% that were initially left out were then classified using the model. This process was carried out a total of 10 times with a different randomly selected 20% left out each time. In lieu of an independent validation set, this approach provides an estimation of the accuracy of the model for classification. The optimized model was applied to the entire section image and visualized as a classification image. Finally, a section from a different animal was classified using the Genetic Algorithm model and the classification image generated.

Protein Identification

Proteins were putatively identified by comparison and mass matching to samples previously identified from samples of the same cell and organism [11, 14, 27, 28]. Briefly, previous identifications were carried out through tissue homogenization and liquid chromatography separation of the soluble protein component with fractions collected by time. MALDI spectra were collected from each fraction and those containing the masses of interest were further separated on a 1D PAGE gel. Gel bands corresponding to the protein of interest were cut out and subjected to in-gel tryptic digestion and proteins were identified by peptide mass fingerprinting and MS/MS of the peptides.

Results

MR imaging of bone metastasis allows for accurate registration to the blockface image volume and subsequently the MALDI IMS data

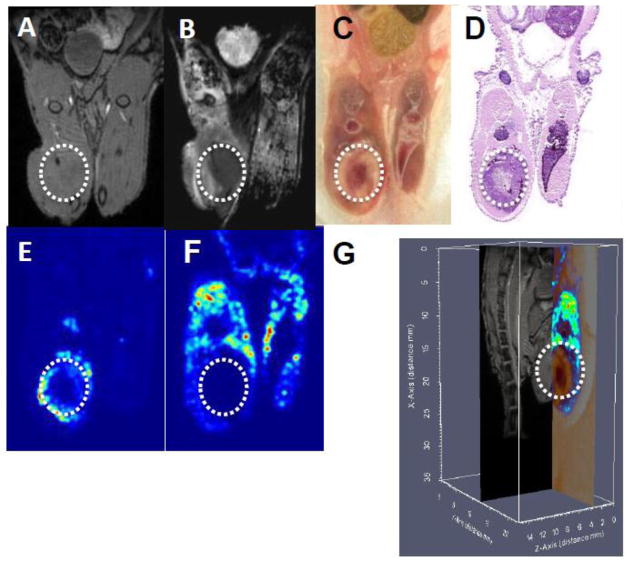

T1-weighted MR images and ADC maps of the tumor in bone provided anatomical and cellularity assessments of the tumor and surrounding tissue in the live animal, respectively (Figure 3A&B). These MR images were then aligned with an image of the blockface and H&E stained section, providing an assessment of relative amounts of nucleic acid and protein at the cellular level in frozen tissue (Figure 3C&D). Due to the rigid nature of section collection using the tape transfer system, mass spectral images could be mapped directly onto the corresponding blockface images for co-registration of these two modalities. A protein with m/z 10090 as determined by MALDI IMS is found within the viable portion (not necrotic) of the tumor (Figure 3E), while the pattern of expression of a protein with m/z 11838 that is specific for murine muscle tissue provides molecular information that corresponds to the anatomical and cellular information provided in previous panels (Figure 3F). The T1-weighted MR image, blockface, and m/z 11838 protein images were co-registered in a three dimensional image that allows simultaneous visualization of anatomical and molecular information (Figure 3G).

Figure 3. Co-registration of anatomical and molecular images.<.

br>Intratibially-injected MDA-MB-231 cells were allowed to grow for four weeks in the murine bone microenvironment (tumors indicated by the white circle). The mouse leg was imaged by MRI to produce T1-weighted (A) and ADC (B) images. The animal was sacrificed and the tissue frozen. (C) Images of the blockface were collected throughout the entire animal. (D) A section of the animal containing tumor was analyzed by H&E staining, and the adjacent section by MALDI IMS. A protein at m/z 10090 corresponds to viable tumor (E) and at m/z 11838 corresponds to skeletal muscle tissue (F). (G) Co-registered blockface (true color), T1-weighted MRI (grayscale), and MALDI IMS measurements for m/z 11838 (false color). The color bar on the left depicts relative protein concentration from low (blue) to high (red). The grayscale color bar represents relative MR signal intensity where white corresponds to maximum values. Axes scales are in millimeters.

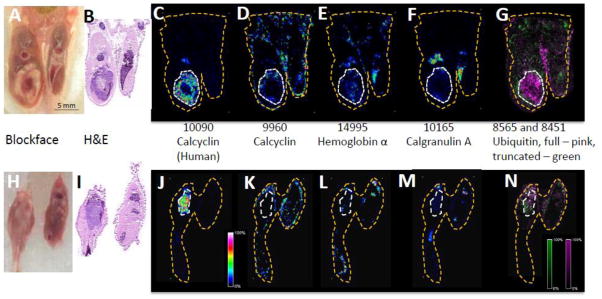

IMS allows for identification of tumor-specific protein profiles

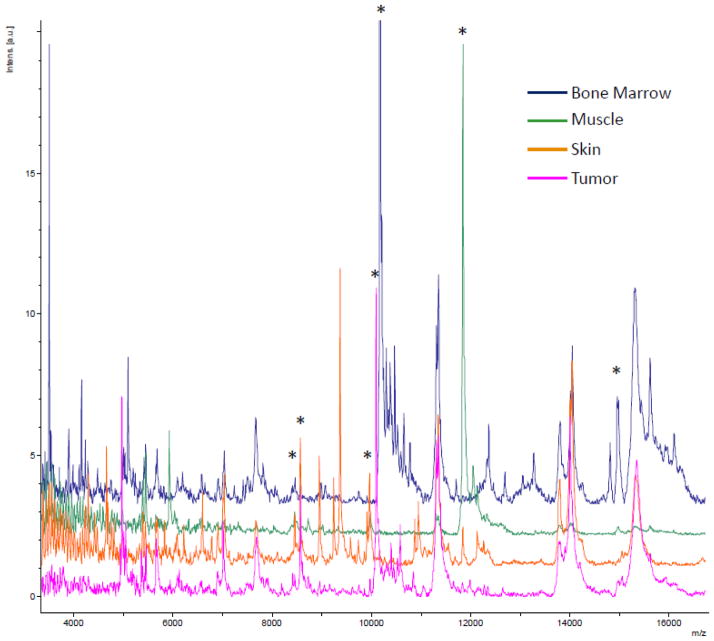

The MALDI IMS images provide spatial information on the molecular composition of specific regions of the tumor, adjacent surrounding tissue, and normal tissue. The average spectra per area are shown in Figure 4. While there are large variations in the intensities of different peaks, it is important to note that these may not reflect the relative abundance of one protein compared to another. There are many factors that can influence the observed relative intensity of a peak including ionization efficiency (basicity) as well as the actual concentration of a given protein. Thus, conclusions of relative abundance can only made for a single protein and not between different proteins. From these data specific peaks were isolated and shown in co-registration images in Figure 5. Reported protein identifications are consistent with those identified from previous work in our lab with similar tissue types. Where appropriate, references for these identifications are provided. The human form of calcyclin (S100A6), m/z 10090, [29] an EF-hand calcium-binding protein that is associated with cellular proliferation, differentiation, and secretion,[30] is detected at high levels in the viable MDA-MB-231 tumor cells but not in the necrotic core of a mouse with a very large tumor (Figure 5C). In a mouse with a much smaller tumor, the expression of human calcyclin corresponds to the entire tumor area (Figure 5J). Human calcyclin can be easily distinguished by MALDI IMS from murine calcyclin, m/z 9960, [28] which localizes in normal mouse tissues, mostly skin, as well as at the edge of the tumor where there is a mixture of mouse and human cells (Figure 5D&K). These two protein forms are indistinguishable by antibody staining. Hemoglobin a, m/z 14995, indicates vascular areas in both the tumor and normal tissue containing erythrocytes (Figure 5E&L). Calgranulin A (S100A8), m/z 10165, [14] another EF-hand calcium binding protein in the S100 family, is expressed in particular in granulocytes [31] and displays a distinct pattern of expression in normal bone marrow and along the tumor margin and adjacent tissue (Figure 5F&M). Additionally, ubiquitin, both full length and truncated forms [27], can be observed within the tumor and surrounding tissue (Figure 5G&N). The truncated form is observed more at the advancing, more proliferative edge of the tumor. The extension of the larger tumor throughout the bone marrow of the injected leg can be inferred from the presence of human calcyclin in areas rich in murine hemoglobin and murine calgranulin in the tissue above the tumor (Figure 5C,E&F). The smaller tumor in the lower panels can be inferred to be composed primarily of human tumor cells with little host infiltration as judged by the relative lack of murine calcyclin, hemoglobin, and calgranulin. The information provided by this technology provides insights into the patterns observed at the cell and tissue level in the blockface and H&E analysis that can then inform the images obtained by MRI in the living animal.

Figure 4. Average spectra from selected areas from IMS data.

A selected m/z range from the average spectra from the regions (bone marrow – blue, muscle – green, skin – orange, and tumor – pink) used in generating the class imaging model. Many peaks are observed to differ between cell types. Peaks that are shown in the mass spectra images are indicated by *. Most of these peaks are also part of the classification model in Figure 6.

Figure 5. MALDI IMS images of human breast tumor cells in the murine bone.

Immunodeficient mice were injected with human MDA-MB-231 cells intratibially and tumors analyzed by MALDI IMS after 4 weeks. The tumor in the mouse represented in panels A-G is 33.34 mm3 (the same mouse as shown in Fig. 1), whereas the tumor in the mouse represented in panels H-N is 22.01 mm3 as determined by the ADC map. (A, H) The blockface images and (B,I) corresponding H&E sections, and (C,J) MALDI IMS images of human calcyclin (m/z 10090), (D,K) murine calcyclin (m/z 9960), (E, L) hemoglobin α (m/z 14995), (F, M) calgranulin A (m/z 10165), and (G, N) full length (pink) and truncated (green) ubiquitin (m/z 8565 and 8451). The white dashed lines were drawn around the tumor areas in panels B and I and transferred to corresponding areas in the other panels. The yellow dashed lines correspond to the total area from which data were collected.

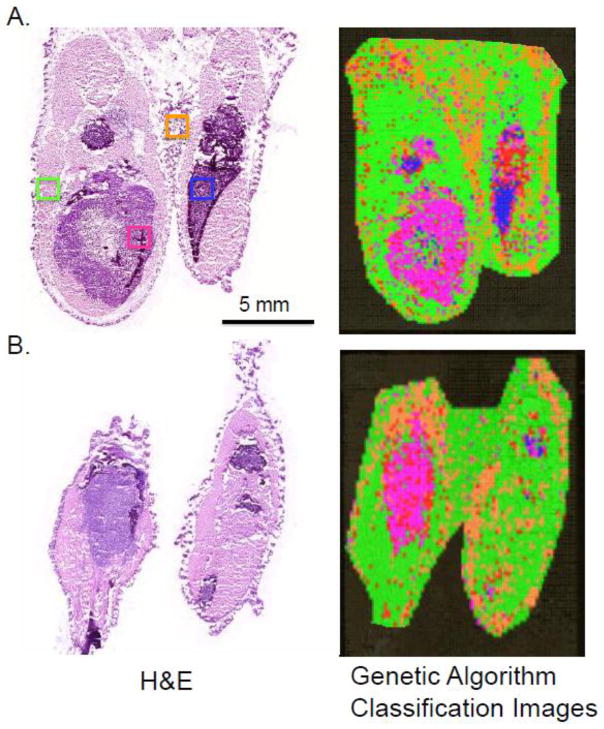

Using a classification algorithm, IMS can be used to detect tumor tissue in bone

Detecting tumor cells in bone while they are still small can be challenging even with H&E stained sections. The application of a classification model to an entire IMS dataset to produce a class image has been used in soft tissue studies to differentiate between tumor cells and normal tissues [32]; however, this has not been applied to tumors residing in bone. Firstly regions of interest based on histological analysis from the H&E section with an obvious tumor were chosen to develop a Genetic Algorithm classification model consisting of 14 protein peaks. Using an internal leave-20%-out cross validation, a spectral classification accuracy of 86% was achieved. This provides a measure of the effectiveness of the model at classifying spectra according to cell type. This model was applied to the entire image data set and visualized as a class image where each color corresponds to the type of tissue as determined by the model. As compared to the serial H&E stained section, a high degree of similarity was obtained, even in the detection of a separate area of tumor in the thigh of the animal (Figure. 6A). Areas corresponding to bone could not be classified as their spectra did not match any of the cell types that were part of the model. Finally, the model was also applied to an entire image data set from another animal and evaluated by comparison to its serial H&E section. As presented in Figure 6B, this algorithm was able to accurately identify whether tissue was muscle, skin, marrow, or tumor.

Figure 6. Predicting tumor using class imaging generated from IMS data.

Small regions of interest corresponding to muscle, skin, marrow, and tumor were selected from one section to generate the model and then applied to the entire section. (A) The section that was used to generate the model with ROIs indicated. Class imaging shows excellent correlation to the H&E stained section. (B) The classification algorithm was applied to a tumor containing section from a second animal and the classification image results also show good correlation with histology. Green – muscle; orange – skin; blue – marrow; pink – tumor; red – unclassified (mostly bone).

Discussion

In this study, we report for the first time the co-registration of molecular (MALDI IMS), cellular (histology), and anatomical (MRI) images of tumors residing in bone, and one of the few studies in a tissue outside of the brain. Applying this technology outside of the brain has been challenging, since the brain tissue is enclosed by the rigid skull that provides a stabilizing structure and fiducial markers, whereas the soft tissue and movement of the hind limbs makes registration between the in vivo and ex vivo images difficult.

We embarked on these studies with the goal of pushing imaging technologies to allow us to better understand the makeup of the bone microenvironment at the protein level in the context of breast tumor metastasis. In order to improve our understanding at the cellular and molecular level, more comprehensive and integrated imaging is required. MR imaging provided in vivo structural images allowing longitudinal study of the pathology of the disease. Importantly, MR images will allow for the registration of other 3D in vivo imaging techniques back to the block face. In this case, we did not add a secondary in vivo image, but PET, CT or other imaging modalities could easily be registered with the MRI data. These structural scans also facilitate the connection between the in vivo study and the ex vivo MALDI IMS imaging through registration to the reconstructed blockface imaging. While these studies were very promising, care must be taken between the MR imaging session and subsequent freezing, sectioning and blockface imaging to keep the region of interest rigid in order to provide an accurate registration between the two images; hence, the need for the rigid apparatus attached to each specimen and presented in Figure 1E.

The mass spectrometry approach is particularly exciting as it will allow us to examine changes in protein profiles within the intact bone micro-environment and solid tumor in response to drug treatment, a goal that has not previously been possible in tumor bearing bones. Molecular signatures of tumor aggressiveness and response to treatment may be used to determine the appropriate treatment for a particular tumor and may also be useful as a potential indicator of therapeutic efficacy. It is also notable that these technologies may identify proteins associated with progression of the tumor growth that could serve as new therapeutic targets.

From the IMS experiments, we were able to putatively identify several proteins that were specific to the tumor region within the mouse hind limb. Identifications are consistent with previous IMS studies with similar tissues [14, 27–29]. Human calcyclin and ubiquitin were found throughout the tumor, while murine hemoglobin was localized to vascular areas of the tumor. The observation of the truncated form of ubiquitin has previously been reported in nephrotoxicity due to gentamycin treatment [27] and in metastatic melanomas with poor survival outcomes [33]. The presence of the truncated form indicates this is a highly aggressive, proliferating tumor where cells are rapidly moving through the cell cycle.

Murine calgranulin was recruited to the periphery of the tumor as part of the innate immune response; it should be noted that the animals used in these studies lack functional T cells and therefore a prolonged inflammatory response would not be achieved as a result of the tumor injection. The detection of proteins that were specific to different cell types within the animal allowed for a classification model to be developed that was successfully applied to another dataset and may, therefore, be applicable to other murine disease models.

Additionally, the use of the classification algorithm may allow us in the future to predict whether a specimen contains tumor or tumor associated stroma. MALDI IMS may allow for early detection of molecular changes associated with tumor progression and growth before they are detectable by histology, which could provide valuable information about the disease pathology. While this will require more experiments to better understand the parameters, in the future this kind of technology could be applied to patient biopsies to determine if tumor is present in samples that may present with ambiguous histology.

While we believe that this technology holds much promise to improve our understanding of the interactions between tumor and bone, the techniques are challenging and the resources are limited to only a few institutions. However, the availability to co-register in vivo and ex vivo imaging may be more broadly applicable as the registration technology becomes more widely accessible. Currently, the registration process is cumbersome and requires very skilled personnel. Our access to high end proteomics and imaging resources has allowed us to begin to investigate protein profile changes between the tumor and the host simultaneously.

Traditionally, our ability to study changes in protein expression has been limited to ex vivo antibody techniques such as immunohistochemistry. These technologies allow only a small and focused understanding. Instead, MALDI IMS will allow us to examine many changes at once, and may allow novel factors to be identified. Furthermore, we believe that this technology has a high translational potential and will also allow us to explore changes within the micro-environment in animal models that we have not been able to study previously, including the determination of molecular (as opposed to histological) tumor margins and the detection of micrometastases. A better understanding of the protein profile within the bone micro-environment and the tumor mass could very well result in the development of new therapeutic strategies for identifying and treating bone metastases.

Highlights.

MALDI IMS can be used to examine protein profiles in tumor-bearing bones.

MRI and MALDI were co-registered to analyze a tumor-induced bone disease model.

Protein profile peaks alone could determine the presence of tumor.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institute of Health for funding via U54CA126505, 5R01GM058008, P01CA040035, and 5P30CA068485, and 5R01CA138599. Funding was also provided via the Department of Defense W81XWH-05-1-0179. J.A.S was supported by a Department of Veterans Affairs Career Development Award. We thank Dr. Tuhin Sinha and Amelie Gilman for their assistance in starting this project. We thank Ms. Jamie Allen, Mr. Steve Munoz, Ms. Alyssa Merkel, Mr. Jarrod True, and Mr. Zhengyu Yang for technical assistance and many informative discussions. Additionally, we thank Mr. Russell Rhoades for grammatical review of this manuscript and Dr. T.J. Martin for his helpful suggestions. Finally, we thank the late Dr. Gregory Mundy for his insightfulness, interest, and early support of this project.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sterling JA, Edwards JR, Martin TJ, Mundy GR. Advances in the biology of bone metastasis: how the skeleton affects tumor behavior. Bone. 2011;48:6–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kakonen SM, Mundy GR. Mechanisms of osteolytic bone metastases in breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:834–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson AW, Xie J, Pizzonia J, Bronen RA, Spencer DD, Gore JC. Effects of cell volume fraction changes on apparent diffusion in human cells. Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;18:689–95. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(00)00147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patterson DM, Padhani AR, Collins DJ. Technology insight: water diffusion MRI--a potential new biomarker of response to cancer therapy. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5:220–33. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaurand P, Schwartz SA, Caprioli RM. Profiling and imaging proteins in tissue sections by MS. Anal Chem. 2004;76:86A–93A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoeckli M, Chaurand P, Hallahan DE, Caprioli RM. Imaging mass spectrometry: A new technology for the analysis of protein expression in mammalian tissues. Nature Med. 2001;7:493–496. doi: 10.1038/86573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaurand P, Norris JL, Cornett DS, Mobley JA, Caprioli RM. New Developments in Profiling and Imaging of Proteins from Tissue Sections by MALDI Mass Spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:2889–2900. doi: 10.1021/pr060346u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schafer R. Ultraflextreme: redefining MALDI mass spectrometry performance. LCGC North Am. 2009:14–15. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwamborn K, Krieg RC, Reska M, Jakse G, Knuechel R, Wellmann A. Identifying prostate carcinoma by MALDI-Imaging. Int J Mol Med. 2007;20:155–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reyzer ML, Caldwell RL, Dugger TC, Forbes JT, Ritter CA, Guix M, Arteaga CL, Caprioli RM. Early Changes in Protein Expression Detected by Mass Spectrometry Predict Tumor Response to Molecular Therapeutics. Cancer Res. 2004;64:9093–9100. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz SA, Weil RJ, Thompson RC, Shyr Y, Moore JH, Toms SA, Johnson MD, Caprioli RM. Proteomic-Based Prognosis of Brain Tumor Patients Using Direct-Tissue Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7674–7681. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caldwell RL, Gonzalez A, Oppenheimer SR, Schwartz HS, Caprioli RM. Molecular assessment of the tumor protein microenvironment using imaging mass spectrometry. Cancer Genomics & Proteomics. 2006;3:279–288. [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Merwe D-E, Oikonomopoulou K, Marshall J, Diamandis Eleftherios P. Mass spectrometry: uncovering the cancer proteome for diagnostics. Adv Cancer Res. 2007;96:23–50. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(06)96002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corbin BD, Seeley EH, Raab A, Feldmann J, Miller MR, Torres VJ, Anderson KL, Dattilo BM, Dunman PM, Gerads R, Caprioli RM, Nacken W, Chazin WJ, Skaar EP. Metal chelation and inhibition of bacterial growth in tissue abscesses. Science. 2008;319:962–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1152449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoeckli M, Knochenmuss R, McCombie G, Mueller D, Rohner T, Staab D, Wiederhold K-H. MALDI MS imaging of amyloid. Methods Enzymol. 2006;412:94–106. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)12007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drexler DM, Garrett TJ, Cantone JL, Diters RW, Mitroka JG, Prieto Conaway MC, Adams SP, Yost RA, Sanders M. Utility of imaging mass spectrometry (IMS) by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) on an ion trap mass spectrometer in the analysis of drugs and metabolites in biological tissues. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2007;55:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khatib-Shahidi S, Andersson M, Herman JL, Gillespie TA, Caprioli RM. Direct Molecular Analysis of Whole-Body Animal Tissue Sections by Imaging MALDI Mass Spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2006;78:6448–6456. doi: 10.1021/ac060788p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoeckli M, Staab D, Schweitzer A. Compound and metabolite distribution measured by MALDI mass spectrometric imaging in whole-body tissue sections. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2007;260:195–202. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andersson M, Groseclose MR, Deutch AY, Caprioli RM. Imaging mass spectrometry of proteins and peptides: 3D volume reconstruction. Nat Methods. 2008;5:101–108. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cornett DS, Mobley JA, Dias EC, Andersson M, Arteaga CL, Sanders ME, Caprioli RM. A novel histology-directed strategy for MALDI-MS tissue profiling that improves throughput and cellular specificity in human breast cancer. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:1975–1983. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600119-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinha TK, Khatib-Shahidi S, Yankeelov TE, Mapara K, Ehtesham M, Cornett DS, Dawant BM, Caprioli RM, Gore JC. Integrating spatially resolved three-dimensional MALDI IMS with in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Nature Met. 2008;5:57–59. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Attia AS, Schroeder KA, Seeley EH, Wilson KJ, Hammer ND, Colvin DC, Manier ML, Nicklay JJ, Rose KL, Gore JC, Caprioli RM, Skaar EP. Monitoring the Inflammatory Response to Infection through the Integration of MALDI IMS and MRI. Cell host & microbe. 2012;11:664–73. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sterling JA, Oyajobi BO, Grubbs B, Padalecki SS, Munoz SA, Gupta A, Story B, Zhao M, Mundy GR. The hedgehog signaling molecule Gli2 induces parathyroid hormone-related peptide expression and osteolysis in metastatic human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7548–53. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson RW, Nguyen MP, Padalecki SS, Grubbs BG, Merkel AR, Oyajobi BO, Matrisian LM, Mundy GR, Sterling JA. TGF-beta promotion of Gli2-induced expression of parathyroid hormone-related protein, an important osteolytic factor in bone metastasis, is independent of canonical Hedgehog signaling. Cancer Res. 2011;71:822–31. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersson M, Groseclose MR, Deutch AY, Caprioli RM. Imaging mass spectrometry of proteins and peptides: 3D volume reconstruction. Nature Methods. 2008;5:101–108. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norris JL, Cornett DS, Mobley JA, Andersson M, Seeley EH, Chaurand P, Caprioli RM. Processing MALDI Mass Spectra to Improve Mass Spectral Direct Tissue Analysis. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2007;260:212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herring KD. Department of Biochemistry. Nasvhille, TN: Vanderbilt University; 2009. Identification of Protein Markers of Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity by MALDI MS: in vivo Discovery of Ubiquitin-t; p. 110. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie L, Xu BJ, Gorska AE, Shyr Y, Schwartz SA, Cheng N, Levy S, Bierie B, Caprioli RM, Moses HL. Genomic and Proteomic Analysis of Mammary Tumors Arising in Transgenic Mice. Journal of Proteome Research. 2005;4:2088–2098. doi: 10.1021/pr050214l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz SA, Weil RJ, Thompson RC, Shyr Y, Moore JH, Toms SA, Johnson MD, Caprioli RM. Proteomic-Based Prognosis of Brain Tumor Patients Using Direct-Tissue Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Cancer Research. 2005;65:7674–7681. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Filipek A, Michowski W, Kuznicki J. Involvement of S100A6 (calcyclin) and its binding partners in intracellular signaling pathways. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2008;48:225–39. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghavami S, Chitayat S, Hashemi M, Eshraghi M, Chazin WJ, Halayko AJ, Kerkhoff C. S100A8/A9: a Janus-faced molecule in cancer therapy and tumorgenesis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;625:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan TM, Seeley EH, Fadare O, Caprioli RM, Clark PE. Imaging the clear cell renal cell carcinoma proteome. J Urol. 2013;189:1097–103. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hardesty WM, Kelley MC, Mi D, Low RL, Caprioli RM. Protein signatures for survival and recurrence in metastatic melanoma. J proteomics. 2011;74:1002–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]