Abstract

Chlorine gas is a widely used industrial compound that is highly toxic by inhalation and is considered a chemical threat agent. Inhalation of high levels of chlorine results in acute lung injury characterized by pneumonitis, pulmonary edema, and decrements in lung function. Because inflammatory processes can promote damage in the injured lung, anti-inflammatory therapy may be of potential benefit for treating chemical-induced acute lung injury. We previously developed a chlorine inhalation model in which mice develop epithelial injury, neutrophilic inflammation, pulmonary edema, and impaired pulmonary function. This model was used to evaluate nine corticosteroids for the ability to inhibit chlorine-induced neutrophilic inflammation. Two of the most potent corticosteroids in this assay, mometasone and budesonide, were investigated further. Mometasone or budesonide administered intraperitoneally 1 h after chlorine inhalation caused a dose-dependent inhibition of neutrophil influx in lung tissue sections and in the number of neutrophils in lung lavage fluid. Budesonide, but not mometasone, reduced the levels of the neutrophil attractant CXCL1 in lavage fluid 6 h after exposure. Mometasone or budesonide also significantly inhibited pulmonary edema assessed 1 day after chlorine exposure. Chlorine inhalation resulted in airway hyperreactivity to inhaled methacholine, but neither mometasone nor budesonide significantly affected this parameter. The results suggest that mometasone and budesonide may represent potential treatments for chemical-induced lung injury.

Keywords: acute lung injury, pneumonitis, pulmonary edema, corticosteroids

Introduction

Chlorine is a reactive gas used in a variety of industrial processes, including the production of plastics, solvents, paper products, and purified drinking water. Chlorine is considered a chemical threat because of the large amounts that are produced and transported in the U.S., its ease of acquisition, and its acute toxicity (Homeland Security Council, 2004). Chlorine is highly toxic by inhalation, and toxic exposures to humans have occurred from both accidental and intentional releases of chlorine. Chlorine poisoning can occur in household or swimming pool accidents involving cleaning supplies and disinfectants (Deschamps et al., 1994; Agabiti et al., 2001). Toxic exposures have also occurred through accidental chlorine release in industrial settings (Evans, 2005) and as a result of train derailments during transport (Joyner and Durel, 1962; Weill et al., 1969; Jones et al., 1986; Van Sickle et al., 2009). Chlorine has been used as a chemical weapon, first in World War I and most recently in the Iraq war, during which insurgents executed a series of attacks involving chlorine gas. The most serious domestic threat for intentional chlorine release likely involves attack on industrial storage facilities or rail cars during transport, which potentially could lead to large number of casualties (Homeland Security Council, 2004). We are investigating treatments for chlorine-induced lung injury with an ultimate goal of developing medical countermeasures that could be rapidly administered if needed in such a mass casualty scenario.

Both acute and chronic lung conditions have inflammatory components that contribute to disease pathogenesis. Corticosteroids are potent anti-inflammatory agents and have been widely used in the treatment of lung diseases such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and interstitial lung diseases. Because pulmonary inflammation is an integral part of acute lung injury/adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), corticosteroids have been investigated for treatment of this clinical condition. Treatment of patients with sepsis at risk for developing ARDS with early high-dose corticosteroids was not effective in preventing the progression to ARDS or in inhibiting mortality (Peter et al., 2008). Benefits of low-dose corticosteroids initiated during established ARDS have been suggested in some studies (Meduri et al., 1998; Meduri et al., 2007), but these findings have not been universally reproduced (Steinberg et al., 2006; Peter et al., 2008). Assessment of the value of corticosteroids in treating acute lung injury/ARDS has been complicated by variability in treatment regimen (e.g. high/low dose, early/late treatment) (Peter et al., 2008) and possibly also by the grouping together of ARDS patients with differing etiologies (Donahoe, 2011). The underlying risk factors for the large majority of ARDS cases are either indirect injury or pneumonia; only a small minority of cases results from direct pulmonary damage from an inhaled agent. Chemical lung injury may have distinct pathological features and disease progression compared with typical ARDS cases, and consequently may have differential responses to therapy. Victims of chlorine poisoning are typically administered corticosteroids (Van Sickle et al., 2009), although the optimal treatment regimen for this indication has not been investigated. In the present study, we screened a panel of corticosteroids for anti-inflammatory effects following chlorine inhalation in mice and characterized the effects of two of the most potent compounds, mometasone and budesonide, on multiple aspects of chlorine-induced lung injury.

Materials and methods

Materials

Corticosteroids were obtained from the following sources: budesonide, fluticasone, mometasone (Tocris, Ellisville, MO); beclomethasone, flunisolide, hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone, prednisone, triamcinolone (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). ELISA reagents to measure CXCL1 were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Reagents to measure hemoglobin for determination of extravascular lung water were purchased from Arbor Assays (Ann Arbor, MI). Ly-6G antibody (clone 1A8) to detect neutrophils in lung tissue sections was obtained from BD Biosciences Pharmingen (San Diego, CA).

Animals

All experiments involving animals were carried out in accordance with the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of Louisville Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were housed in microisolator cages in a specific pathogen-free rodent facility accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). Eight week-old FVB/N mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Mice were housed for 1–2 weeks and randomly assigned to exposure and treatment groups. Mice were administered buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg s.c.) for analgesia immediately after chlorine exposure and b.i.d. until euthanized. Groups of mice not exposed to chlorine received buprenorphine treatment on the same schedule as chlorine-exposed mice.

Chlorine exposure

Whole body exposure to chlorine gas was performed in a 54 L polyester cabinet housed within a secondary containment chamber (Tian et al., 2008). Gas from a chlorine source (1% chlorine in nitrogen; Airgas Specialty Gases, Riverton, NJ) was diluted with room air to achieve the desired exposure concentrations. The chlorine exposure dose was determined by iodometric analysis of an air sample collected into 1% sulfamic acid as described (Rando and Hammad, 1990), except that chlorine levels (as produced iodine) were measured spectrophotometrically at 405 nm rather than by specific-ion electrode. Real-time monitoring of chamber chlorine concentration profiles was performed using an X-STREAM 2 gas analyzer (Rosemount Analytical, Solon, OH). Chlorine flow was provided to the chamber for a nominal 1-hr exposure time followed by a 10-min period of air flow only to purge the chamber before opening. Target exposure dose was 240 ppm-hr; actual exposures averaged 240±6 ppm-hr (mean±SD).

Administration of corticosteroids

Test compounds were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 6.7 mg/ml and then diluted with Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline to prepare solutions for injection. For dose-response experiments, dilutions were performed to hold the solvent concentration constant in all doses and in the vehicle (2.25% DMSO). Test compounds were administered i.p. b.i.d. starting 1 hr after the end of the chlorine exposure until the animals were euthanized.

Analysis of chlorine-induced lung injury

Analysis of lung histology, immunohistochemistry for the neutrophil marker Ly-6G, lavage fluid cell differential, lavage fluid protein, and lavage fluid CXCL1 were performed as described (Tian et al., 2008; Hoyle et al., 2010b). Extravascular lung water was measured according to published methods (Su et al., 2007). Pulmonary function and airway reactivity to methacholine were measured by forced oscillation using a FlexiVent system (SCIREQ, Montreal, Quebec, Canada). Mice were anesthetized with tribromoethanol (375 mg/kg i.p.), and a tracheal cannula was inserted and connected to a ventilator and pressure transducer. Mice were placed on a warming plate, attached to EKG leads, and mechanically ventilated with a tidal volume of 6 ml/kg at 150 breaths/min. Mice were administered pancuronium bromide (0.8 mg/kg i.p.) to inhibit endogenous breathing effort. Baseline measurements of respiratory system resistance and compliance were collected, as well as lung mechanics parameters calculated from fitting lung impedance data to the constant-phase model (Hantos et al., 1992; Tomioka et al., 2002). Following baseline respiratory measurements, mice were administered increasing doses of aerosolized methacholine (generated from solutions of 1.6, 3.1, 6.3, and 12.5 mg/ml) to measure airway reactivity. Methacholine was aerosolized for 10 sec from an Aeroneb nebulizer that delivered 0.15 ml/min, and respiratory parameters were repeatedly collected for a total of 15 measurements of each parameter. For each methacholine dose, the average of the 15 measurements was calculated.

Data analysis

Data are presented as group means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Effects of treatment on airway reactivity to methacholine were analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Effects of exposure condition/treatment on other parameters were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test. Data were transformed before analysis if necessary to produce normally distributed data. Differences were considered to be statistically significant at the p<0.05 level.

Results

Relative potency of corticosteroids in inhibiting chlorine-induced lung inflammation

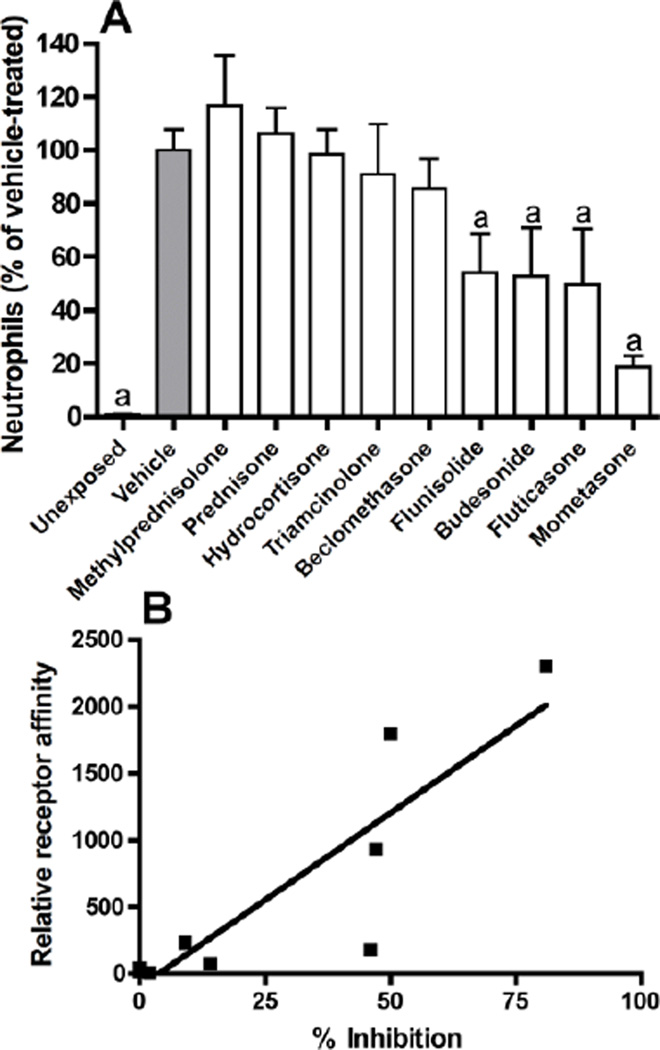

In a previous study, we characterized indices of lung injury and inflammation induced by chlorine inhalation (Tian et al., 2008). In the present study, nine corticosteroids were evaluated in initial experiments to compare their ability to inhibit neutrophils in lavage fluid 48 h after chlorine exposure (Fig. 1A). FVB/N mice were exposed to chlorine gas and treated intraperitoneally with corticosteroids at 3 mg/kg b.i.d. starting 1 h after exposure until analysis by lung lavage 48 h after exposure (total of four doses). Neutrophils were measured as the percentage of vehicle-treated (100%) and were significantly decreased in lung lavage fluid by flunisolide (46%), budesonide (47%), fluticasone (50%), and mometasone (82%). Comparison of the percent inhibition of lavage fluid neutrophils with the relative affinities of the corticosteroid ligands for the glucocorticoid receptor revealed a significant correlation between the two indices (Figure 1B), indicating that the receptor binding affinity was the most important determinant of the potency for inhibition of chlorine-induced neutrophil influx.

Figure 1. Inhibition of chlorine-induced neutrophilic inflammation by corticosteroids.

Mice were exposed to chlorine and treated with the indicated corticosteroids i.p. at 3 mg/kg starting 1 h after exposure and then b.i.d. thereafter until euthanized for lung lavage and enumeration of neutrophils 48 hr after exposure. Panel A shows the percent inhibition of the number of neutrophils in lavage fluid relative to chlorine-exposed, vehicle treated mice (gray bar). a, p<0.01 vs. chlorine-exposed, vehicle-treated. Panel B shows a significant correlation between the percent inhibition for the individual compounds and their relative affinity for the glucocorticoid receptor (Rohdewald et al., 1985; Mager et al., 2003; Winkler et al., 2004); r2=0.77, p<0.01.

Effects of mometasone and budesonide on chlorine-induced inflammation and injury

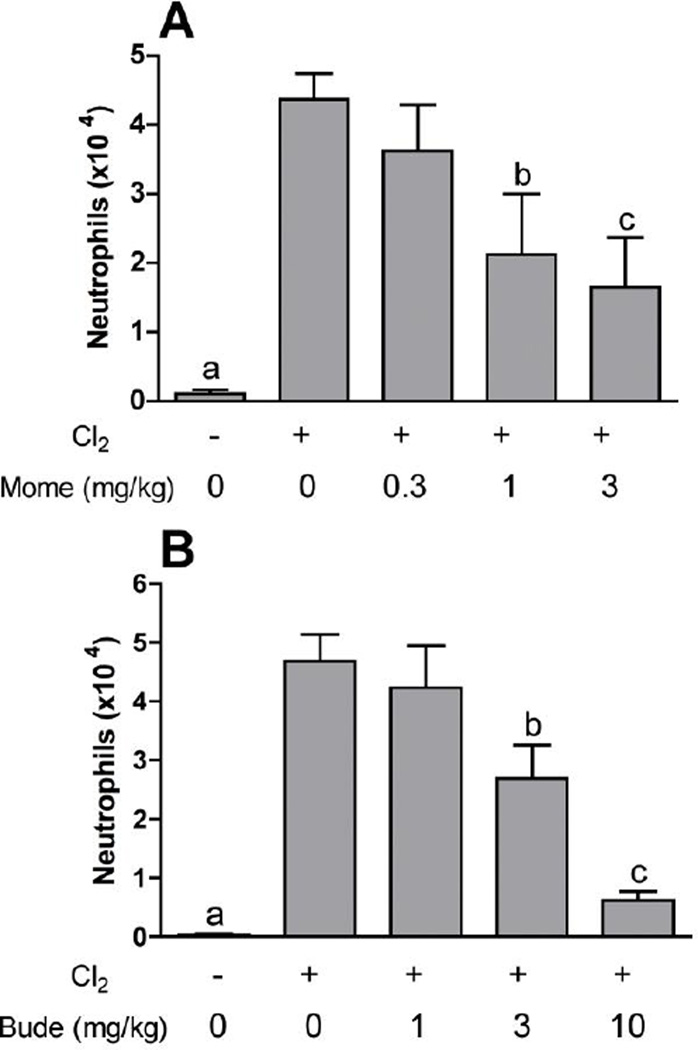

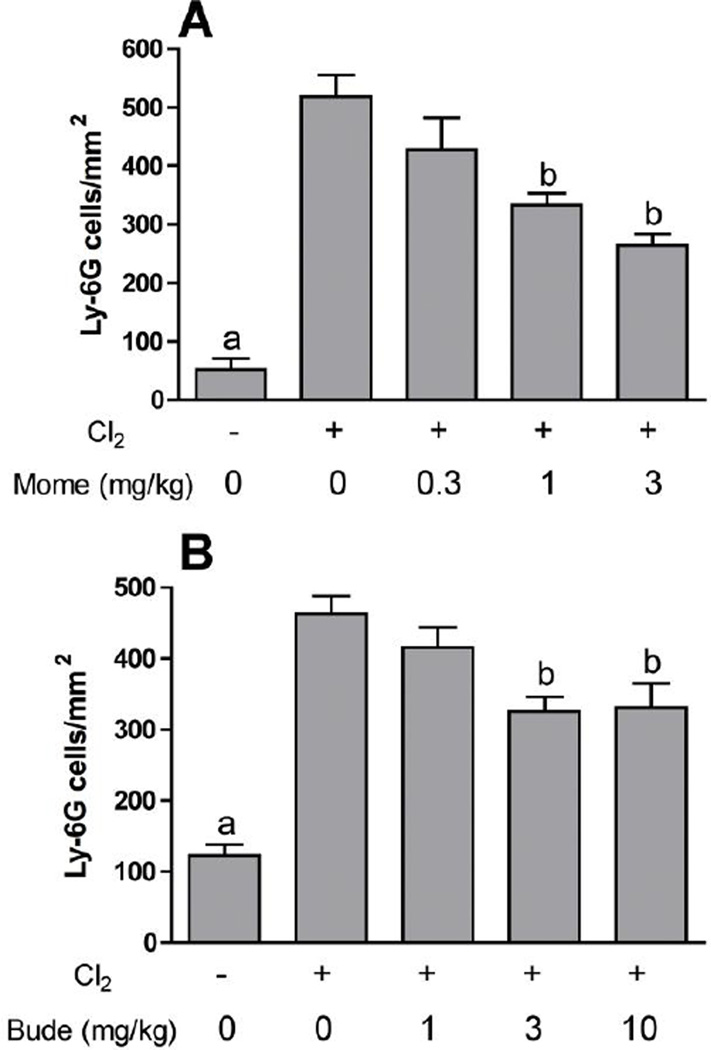

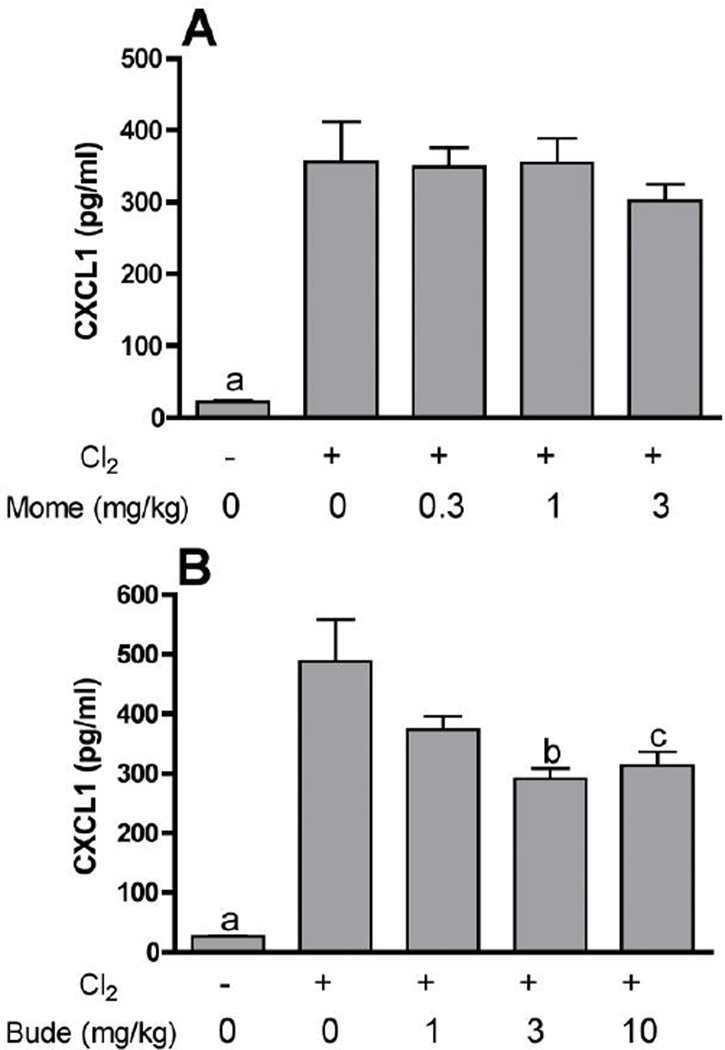

Further experiments were performed with mometasone and budesonide, two of the corticosteroid compounds showing high potency against chlorine-induced neutrophil influx. Lavage fluid neutrophils were inhibited by mometasone and budesonide in a dose-dependent manner in chlorine-exposed animals (Fig. 2). In our previously established animal model we documented the initial influx of neutrophils in lung tissue sections with a peak 6 hr after exposure. This neutrophilic inflammation was correlated with an increased level in lavage fluid of the chemokine CXCL1, which peaked at 6 hr after exposure. Therefore, we examined the effect of corticosteroid treatment on these additional parameters associated with chlorine-induced neutrophilic inflammation. Treatment with mometasone or budesonide inhibited in a dose-dependent manner the number of cells staining with the neutrophil marker Ly-6G in lung tissue sections from chlorine-exposed mice 6 hr after exposure (Fig. 3). Budesonide, but not mometasone, inhibited the amount of CXCL1 measured in lavage fluid 6 hr after chlorine exposure (Fig. 4).

Figure 2. Inhibition of lavage fluid neutrophils by mometasone and budesonide.

Mice were exposed to chlorine and treated with mometasone (A) or budesonide (B) i.p. at the indicated doses starting 1 h after exposure and then b.i.d. thereafter until euthanized for lung lavage and enumeration of neutrophils 48 hr after exposure. The maximum dose of mometasone was limited to 3 mg/kg because of the limited solubility of this compound. a, p<0.01 vs. all other groups; b, p<0.05 vs. chlorine, no corticosteroid; c, p<0.01 vs. chlorine, no corticosteroid.

Figure 3. Inhibition of lung neutrophil influx by mometasone and budesonide.

Mice were exposed to chlorine and treated with mometasone (A) or budesonide (B) i.p. at the indicated doses 1 h after exposure. Mice were euthanized for lung fixation 6 hr after exposure, and sections were stained for the neutrophil marker Ly-6G. a, p<0.001 vs. all other groups; b, p<0.01 vs. chlorine, no corticosteroid.

Figure 4. Effect of mometasone and budesonide on lavage fluid CXCL1.

Mice were exposed to chlorine and treated with mometasone (A) or budesonide (B) i.p. at the indicated doses 1 h after exposure. Mice were euthanized for lung lavage 6 hr after exposure for measurement of CXCL1 by ELISA. a, p<0.001 vs. all other groups; b, p<0.05 vs. chlorine, no budesonide; c, p<0.01 vs. chlorine, no budesonide.

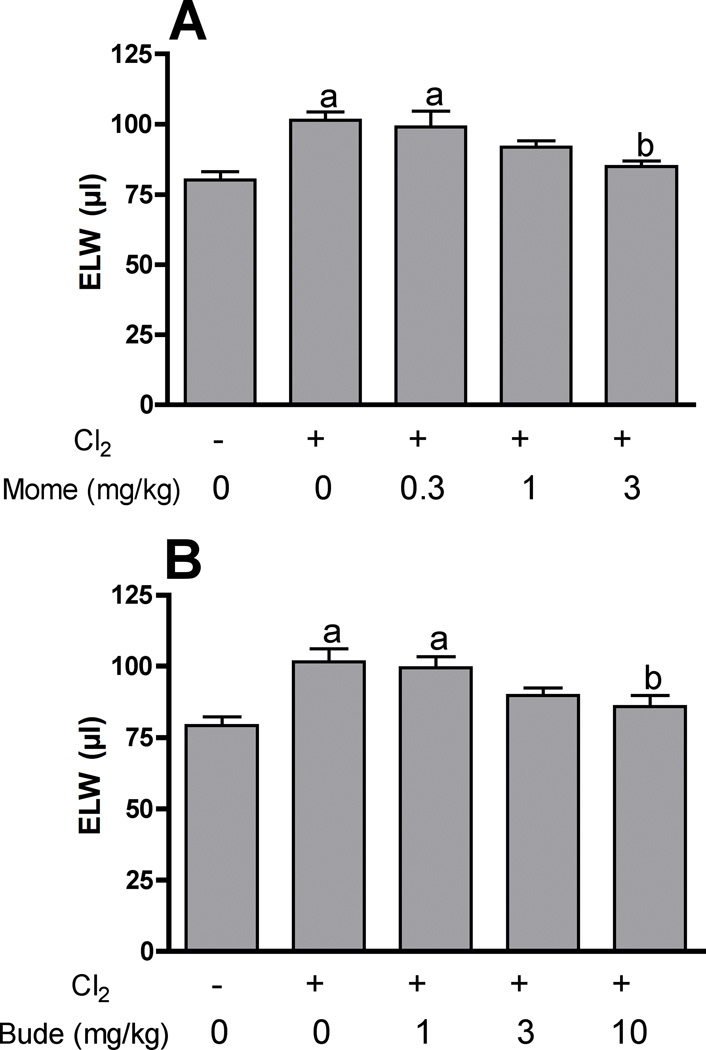

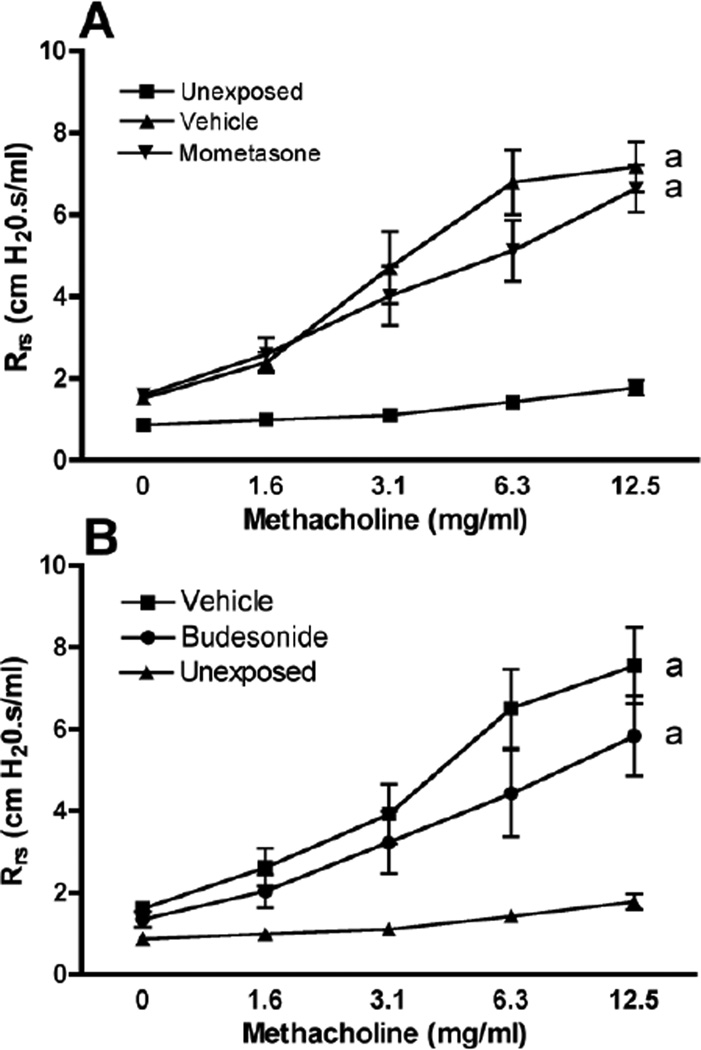

Chlorine inhalation causes acute lung injury characterized by pulmonary edema and airway hyperreactivity (Tian et al., 2008; Hoyle et al., 2010a; Song et al., 2011). In order to assess the effects of mometasone and budesonide on chlorine-induced pulmonary edema, we measured extravascular lung water at 24 hr after chlorine exposure. Mometasone and budesonide significantly reduced extravascular lung water by 77% and 70%, respectively, at the highest dose tested (Fig. 5). Chlorine inhalation also induced airway hyperreactivity to inhaled methacholine (Fig. 6). Neither mometasone nor budesonide significantly affected airway reactivity in chlorine-exposed mice.

Figure 5. Inhibition of chlorine-induced pulmonary edema by mometasone and budesonide.

Mice were exposed to chlorine and treated with mometasone (A) or budesonide (B) i.p. at the indicated doses 1 h and 10 h after exposure. Twenty-four h after exposure lungs were collected to measure extravascular lung water (ELW). a, p<0.01 vs. no chlorine; b, p<0.05 vs. chlorine, no corticosteroid.

Figure 6. Effect of mometasone and budesonide on airway reactivity.

Mice were exposed to chlorine and treated with mometasone (A) or budesonide (B) i.p. at the indicated doses 1 and 10 h after exposure and then the following day 2 h before lung function measurements. Rrs, respiratory system resistance. a, dose-response curves different at p<0.01 vs. unexposed.

Discussion

Chlorine inhalation results in direct damage to the respiratory tract, producing injured epithelial and endothelial cells, vascular leakage, inflammation, hypoxemia, pulmonary edema, and lung function abnormalities (White and Martin, 2010). Lung damage from chlorine inhalation triggers an inflammatory response typical of chemical injury characterized by fluid leak and influx of neutrophils into the lung. Neutrophils can exert beneficial effects to limit infection and promote repair (Balamayooran et al., 2010; Zemans et al., 2011), but they may also contribute to further injury through the release of toxic mediators, particularly under conditions of excessive or uncontrolled inflammatory responses (Folkesson et al., 1995; Abraham et al., 2000; Grommes and Soehnlein, 2011; Tao et al., 2012). We have demonstrated that chlorine inhalation in mice causes a rapid influx of neutrophils into the lung parenchyma within 6 hr after exposure, followed by the clustering of neutrophils around damaged airways by 12–24 h, and increasing numbers of neutrophils in lavage fluid out to 48 hr (Tian et al., 2008). These observations suggest the possibility that inflammatory processes can contribute to both alveolar and airway injury after chlorine inhalation.

Mometasone was the most potent corticosteroid tested in an initial screen for effects on lavage fluid neutrophils in chlorine-exposed mice. The effectiveness in this assay was significantly correlated with glucocorticoid receptor binding affinity, indicating that the latter property was the most important determinant of the potency for inhibition of chlorine-induced neutrophil influx. Flunisolide was the only compound tested that did not fall close to the regression line and exhibited a high degree of anti-inflammatory activity in this model compared to that predicted by its relative receptor affinity (Figure 1B). The reason for this behavior is not clear, as flunisolide has shown expected potency based on receptor affinity using other measures (Rohdewald, 1998; Colice, 2000). Budesonide and fluticasone also inhibited chlorine-induced neutrophil influx when administered at 3 mg/kg in a manner that correlated with receptor binding affinity.

Mometasone and budesonide inhibited multiple aspects of chlorine-induced lung injury, including neutrophil influx into the lung 6 hr after exposure, the number of neutrophils in lung lavage fluid at 48 hr, and pulmonary edema at 24 hr, and these effects were in accordance with the known mechanisms of action of corticosteroids. Corticosteroids produce anti-inflammatory effects by multiple mechanisms, the most important of which is transcriptional repression of proinflammatory genes via interference with the activity of transcription factors such as NF-κB and AP-1 (Smoak and Cidlowski, 2004). Although budesonide inhibited CXCL1, it was surprising that mometasone treatment failed to inhibit the production of this NF-κB-regulated gene that we have shown to be associated with neutrophilic inflammation in the lungs of chlorine-exposed mice (Tian et al., 2008; Hoyle et al., 2010b). Treatment of chlorine-exposed mice with triptolide, another anti-inflammatory agent that interferes with NF-κB-mediated transcription, reduced both CXCL1 production and neutrophilic inflammation, demonstrating a similar mechanism of action to budesonide, but distinct from mometasone (Hoyle et al., 2010b). As there are multiple types of proinflammatory genes required for neutrophil recruitment, the effects of mometasone on chlorine-induced neutrophilic inflammation may occur through inhibition of other cytokines, cell adhesion molecules, or inflammatory mediators. Treatment with mometasone or budesonide inhibited chlorine-induced pulmonary edema, and this may occur through multiple mechanisms. Neutrophils release substances such as lipid mediators and proteases that promote edema, and inhibition of inflammation by corticosteroids can prevent these processes (Friedman et al., 2000; Toward and Broadley, 2002). However, the dose response relationships for inhibition of inflammation and pulmonary edema in the present study were somewhat different, suggesting an alternative mechanism for effects on pulmonary edema. Corticosteroids also have the capacity to stimulate alveolar fluid clearance through promoting the expression and function of ion channels (Barquin et al., 1997; Dagenais et al., 2001; Itani et al., 2002; Guney et al., 2007). Finally, corticosteroids can exert nongenomic effects on the vasculature that may promote resolution of lung injury and pulmonary edema (Horvath et al., 2007).

In a previous study (Hoyle et al., 2010a), we demonstrated that increases in baseline lung resistance and reactivity to inhaled methacholine following chlorine exposure resulted from changes in the peripheral lung, such as pulmonary edema or heterogeneous airway narrowing, rather than changes in the central airways. In addition, it has been reported that neutrophils mediate airway hyperreactivity in a mouse model involving less severe chlorine injury (McGovern et al., 2012). Because corticosteroids inhibited both neutrophilic inflammation and pulmonary edema in our chlorine exposure model, we considered it possible based on these previous reports that corticosteroids would inhibit airway hyperreactivity. Our results, which show that corticosteroids do not inhibit airway hyperreactivity caused by high-level chlorine exposure, suggest that the airway hyperreactivity is driven by mechanisms other than neutrophil influx and pulmonary edema.

The effects of corticosteroids have been examined previously in chlorine lung injury models. Chlorine lung injury was examined in anesthetized, mechanically ventilated pigs (Gunnarsson et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2005). In this model, chlorine was introduced into the airways of unconscious animals through an endotracheal tube, in contrast to the whole-body procedure used herein, which more closely replicates the usual route of exposure for chlorine poisoning. Corticosteroids (beclomethasone, budesonide, or betamethasone) administered to chlorine-exposed pigs improved arterial oxygenation, increased lung compliance, reduced pulmonary hypertension, and inhibited pulmonary edema. Beneficial effects of corticosteroids were dependent on administering the compounds within 30 min of exposure (Wang et al., 2002). Inhaled and systemic corticosteroids appeared to be equally effective in inhibiting lung injury (Wang et al., 2005). The effects of i.p. dexamethasone on lung injury in chlorine-exposed rats have been examined (Demnati et al., 1998). Dexamethasone administered immediately after exposure and then daily thereafter inhibited the chlorine-induced increase in airway resistance 3 days after exposure and airway hyperreactivity 2 days after exposure but did not significantly affect these parameters 1 day after exposure. Dexamethasone also inhibited neutrophils in lung lavage fluid 1 day after exposure. Similar to the pig studies, our results showed reduced pulmonary edema with corticosteroid treatment. In contrast to these former studies, we did not observe an effect of mometasone or budesonide treatment on pulmonary edema evaluated 6 hr after exposure (not shown), which could reflect differences in species, chlorine exposure method, conscious vs. anesthetized animals, or inhaled vs. systemic administration of corticosteroids. We also observed significant effects of corticosteroids administered 1 hr after chlorine exposure, which could be an important extension of the window of efficacy if large numbers of patients require simultaneous treatment. We observed inhibition of the initial neutrophil influx into the lungs at 6 hr and of the number of neutrophils in lavage fluid at 48 hr, which was an overall similar effect to the previous rat study considering the different kinetics of chlorine-induced neutrophil influx between the different models (Demnati et al., 1998; Tian et al., 2008). Corticosteroid treatment failed to inhibit airway hyperreactivity to inhaled methacholine in chlorine-exposed mice, which was similar to what was observed in rats (Demnati et al., 1998). We previously reported that rolipram, a type 4 phosphodiesterase inhibitor, inhibited chlorine-induced airway hyperreactivity (Hoyle, 2010). Corticosteroids may be a useful adjunct to phosphodiesterase inhibitor or β-agonist therapy (Song et al., 2011), as corticosteroids can potentially synergize in multiple ways with agents that raise cyclic AMP levels (Skinner et al., 1989; Dagenais et al., 2001; Barnes, 2002; Wang et al., 2004).

The Homeland Security Council has estimated that an attack on an industrial site or train tanker cars leading to the intentional release of chlorine in an urban area could lead to as many as 17,500 deaths and 100,000 hospitalizations from chlorine exposure (Homeland Security Council 2004). A disaster of this magnitude would overwhelm local health care capacity and drives the need for medical countermeasures that could be rapidly administered in the field by personnel with limited medical training. Both inhaled and systemically delivered corticosteroids have been used clinically to treat chlorine-induced lung injury (Van Sickle et al., 2009). Inhaled countermeasures have disadvantages, as these could be difficult to administer to victims who were unconscious or those with lung injury that limited the penetration of inhaled drugs. Systemic corticosteroids are typically given intravenously, but this method is impractical for initial field use with large numbers of casualties because of the time and expertise required. Our results show proof-of-principle for systemic administration of corticosteroids in treating chlorine-induced lung inflammation and pulmonary edema. Future studies will investigate the feasibility of developing formulations that could be used for intramuscular administration of corticosteroids, either alone or in combination with other potential countermeasures, thereby providing a rapid and simple delivery method.

Highlights.

Chlorine causes lung injury when inhaled and is considered a chemical threat agent.

Corticosteroids may inhibit lung injury through their anti-inflammatory actions.

Corticosteroids inhibited chlorine-induced pneumonitis and pulmonary edema.

Mometasone and budesonide are potential rescue treatments for chlorine lung injury.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health CounterACT Program through the Office of the Director and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Award U01 ES015673 to G.W.H.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abraham E, Carmody A, Shenkar R, Arcaroli J. Neutrophils as early immunologic effectors in hemorrhage- or endotoxemia-induced acute lung injury. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2000;279:L1137–L1145. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.6.L1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agabiti N, Ancona C, Forastiere F, Di Napoli A, Lo Presti E, Corbo GM, D'Orsi F, Perucci CA. Short term respiratory effects of acute exposure to chlorine due to a swimming pool accident. Occup. Environ. Med. 2001;58:399–404. doi: 10.1136/oem.58.6.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balamayooran G, Batra S, Fessler MB, Happel KI, Jeyaseelan S. Mechanisms of neutrophil accumulation in the lungs against bacteria. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2010;43:5–16. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0047TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ. Scientific rationale for inhaled combination therapy with long-acting beta2-agonists and corticosteroids. Eur. Resp. J. 2002;19:182–191. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00283202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barquin N, Ciccolella DE, Ridge KM, Sznajder JI. Dexamethasone upregulates the Na-K-ATPase in rat alveolar epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:L825–L830. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.4.L825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colice GL. Comparing inhaled corticosteroids. Respir. Care. 2000;45:846–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagenais A, Denis C, Vives MF, Girouard S, Masse C, Nguyen T, Yamagata T, Grygorczyk C, Kothary R, Berthiaume Y. Modulation of alpha-ENaC and alpha1-Na+-K+-ATPase by cAMP and dexamethasone in alveolar epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2001;281:L217–L230. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.1.L217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demnati R, Fraser R, Martin JG, Plaa G, Malo JL. Effects of dexamethasone on functional and pathological changes in rat bronchi caused by high acute exposure to chlorine. Toxicol. Sci. 1998;45:242–246. doi: 10.1006/toxs.1998.2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps D, Soler P, Rosenberg N, Baud F, Gervais P. Persistent asthma after inhalation of a mixture of sodium hypochlorite and hydrochloric acid. Chest. 1994;105:1895–1896. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.6.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahoe M. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: A clinical review. Pulm. Circ. 2011;1:192–211. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.83454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RB. Chlorine: state of the art. Lung. 2005;183:151–167. doi: 10.1007/s00408-004-2530-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkesson HG, Matthay MA, Hebert CA, Broaddus VC. Acid aspiration-induced lung injury in rabbits is mediated by interleukin-8-dependent mechanisms. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;96:107–116. doi: 10.1172/JCI118009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman E, Novoa E, Crespo A, Marcano H, Pesce L, Comellas A, Sanchez de Leon R. Effect of hydrocortisone on platelet activating factor induced lung edema in isolated rabbit lungs. Respir. Physiol. 2000;120:61–69. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grommes J, Soehnlein O. Contribution of neutrophils to acute lung injury. Mol. Med. 2011;17:293–307. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guney S, Schuler A, Ott A, Hoschele S, Zugel S, Baloglu E, Bartsch P, Mairbaurl H. Dexamethasone prevents transport inhibition by hypoxia in rat lung and alveolar epithelial cells by stimulating activity and expression of Na+-K+-ATPase and epithelial Na+ channels. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2007;293:L1332–L1338. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00338.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsson M, Walther SM, Seidal T, Lennquist S. Effects of inhalation of corticosteroids immediately after experimental chlorine gas lung injury. J. Trauma. 2000;48:101–107. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200001000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantos Z, Daroczy B, Suki B, Nagy S, Fredberg JJ. Input impedance and peripheral inhomogeneity of dog lungs. J. Appl. Physiol. 1992;72:168–178. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.1.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homeland Security Council. The Homeland Security Council, Planning Scenarios: Executive Summaries. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Horvath G, Vasas S, Wanner A. Inhaled corticosteroids reduce asthma-associated airway hyperperfusion through genomic and nongenomic mechanisms. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007;20:157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle GW. Mitigation of chlorine lung injury by increasing cyclic AMP levels. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2010;7:284–289. doi: 10.1513/pats.201001-002SM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle GW, Chang W, Chen J, Schlueter CF, Rando RJ. Deviations from Haber's law for multiple measures of acute lung injury in chlorine-exposed mice. Toxicol. Sci. 2010a;118:696–703. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle GW, Hoyle CI, Chen J, Chang W, Williams RW, Rando RJ. Identification of triptolide, a natural diterpenoid compound, as an inhibitor of lung inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2010b;298:L830–L836. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00014.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itani OA, Auerbach SD, Husted RF, Volk KA, Ageloff S, Knepper MA, Stokes JB, Thomas CP. Glucocorticoid-stimulated lung epithelial Na(+) transport is associated with regulated ENaC and sgk1 expression. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2002;282:L631–L641. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00085.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RN, Hughes JM, Glindmeyer H, Weill H. Lung function after acute chlorine exposure. Am. Rev. Resp. Dis. 1986;134:1190–1195. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.6.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner RE, Durel EG. Accidental liquid chlorine spill in a rural community. J. Occup. Med. 1962;4:152–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mager DE, Lin SX, Blum RA, Lates CD, Jusko WJ. Dose equivalency evaluation of major corticosteroids: pharmacokinetics and cell trafficking and cortisol dynamics. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2003;43:1216–1227. doi: 10.1177/0091270003258651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern TK, Hirota N, Allard-Coutu A, Martin JG. Neutrophils mediate airway hyperresponsiveness following chlorine induced airway injury in the mouse. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012;185:A2836. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0430OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meduri GU, Golden E, Freire AX, Taylor E, Zaman M, Carson SJ, Gibson M, Umberger R. Methylprednisolone infusion in early severe ARDS: results of a randomized controlled trial. Chest. 2007;131:954–963. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meduri GU, Headley AS, Golden E, Carson SJ, Umberger RA, Kelso T, Tolley EA. Effect of prolonged methylprednisolone therapy in unresolving acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:159–165. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter JV, John P, Graham PL, Moran JL, George IA, Bersten A. Corticosteroids in the prevention and treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in adults: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336:1006–1009. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39537.939039.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rando RJ, Hammad YY. A diffusive sampler for gaseous chlorine utilizing an aqueous sulfamic acid collection medium and specific ion electrode analysis. Appl. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 1990;5:700–706. [Google Scholar]

- Rohdewald P, Mollman HW, Hochhaus G. Affinities of glucocorticoids for glucocorticoid receptors in the human lung. Agents Actions. 1985;17:290–291. doi: 10.1007/BF01982622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohdewald PJ. Comparison of clinical efficacy of inhaled glucocorticoids. Arzneimittelforschung. 1998;48:789–796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner SJ, Lowe C, Ashby CJ, Liggins GC. Effects of corticosteroids, prostaglandin E2, and beta-agonists on adenylate cyclase activity in fetal rat lung fibroblasts and type II epithelial cells. Exp. Lung Res. 1989;15:335–343. doi: 10.3109/01902148909087863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoak KA, Cidlowski JA. Mechanisms of glucocorticoid receptor signaling during inflammation. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2004;125:697–706. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Wei S, Liu G, Yu Z, Estell K, Yadav AK, Schwiebert LM, Matalon S. Postexposure Administration of a {beta}2-Agonist Decreases Chlorine-Induced Airway Hyperreactivity in Mice. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2011;45:88–94. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0226OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg KP, Hudson LD, Goodman RB, Hough CL, Lanken PN, Hyzy R, Thompson BT, Ancukiewicz M. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids for persistent acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Eng. J. Med. 2006;354:1671–1684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X, Lee JW, Matthay ZA, Mednick G, Uchida T, Fang X, Gupta N, Matthay MA. Activation of the alpha7 nAChR reduces acid-induced acute lung injury in mice and rats. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2007;37:186–192. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0240OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao W, Miao QB, Zhu YB, Shu YS. Inhaled neutrophil elastase inhibitor reduces oleic acid-induced acute lung injury in rats. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012;25:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X, Tao H, Brisolara J, Chen J, Rando RJ, Hoyle GW. Acute lung injury induced by chlorine inhalation in C57BL/6 and FVB/N mice. Inhal. Toxicol. 2008;20:783–793. doi: 10.1080/08958370802007841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomioka S, Bates JH, Irvin CG. Airway and tissue mechanics in a murine model of asthma: alveolar capsule vs. forced oscillations. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002;93:263–270. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01129.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toward TJ, Broadley KJ. Airway function, oedema, cell infiltration and nitric oxide generation in conscious ozone-exposed guinea-pigs: effects of dexamethasone and rolipram. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;136:735–745. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Sickle D, Wenck MA, Belflower A, Drociuk D, Ferdinands J, Holguin F, Svendsen E, Bretous L, Jankelevich S, Gibson JJ, Garbe P, Moolenaar RL. Acute health effects after exposure to chlorine gas released after a train derailment. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2009;27:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Winskog C, Edston E, Walther SM. Inhaled and intravenous corticosteroids both attenuate chlorine gas-induced lung injury in pigs. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2005;49:183–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2004.00563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhang L, Walther SM. Inhaled budesonide in experimental chlorine gas lung injury: influence of time interval between injury and treatment. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:352–357. doi: 10.1007/s00134-001-1175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhang L, Walther SM. Administration of aerosolized terbutaline and budesonide reduces chlorine gas-induced acute lung injury. J. Trauma. 2004;56:850–862. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000078689.45384.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weill H, George R, Schwarz M, Ziskind M. Late evaluation of pulmonary function after acute exposure to chlorine gas. Am. Rev. Resp. Dis. 1969;99:374–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White CW, Martin JG. Chlorine gas inhalation: human clinical evidence of toxicity and experience in animal models. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2010;7:257–263. doi: 10.1513/pats.201001-008SM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler J, Hochhaus G, Derendorf H. How the lung handles drugs: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of inhaled corticosteroids. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2004;1:356–363. doi: 10.1513/pats.200403-025MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemans RL, Briones N, Campbell M, McClendon J, Young SK, Suzuki T, Yang IV, De Langhe S, Reynolds SD, Mason RJ, Kahn M, Henson PM, Colgan SP, Downey GP. Neutrophil transmigration triggers repair of the lung epithelium via beta-catenin signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:15990–15995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110144108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]