Abstract

Study Design

A secondary analysis comparing diabetic patients with nondiabetic patients enrolled in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT).

Objective

To compare surgical outcomes and complications between diabetic and nondiabetic spine patients.

Summary of Background Data

Patients with diabetes are predisposed to comorbidities that may confound the diagnosis and treatment of patients with spinal disorders.

Methods

Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 199 patients with diabetes were compared with those of the nondiabetic population in a total of 2405 patients enrolled in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial for the diagnoses of intervertebral disc herniation (IDH), spinal stenosis (SpS), and degenerative spondylolisthesis (DS). Primary outcome measures include the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) Health Status questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Index.

Results

Patients with diabetes were significantly older and had a higher body mass index than nondiabetic patients. Comorbidities, including hypertension, stroke, cardiovascular disease, and joint disease, were significantly more frequent in diabetic patients than in nondiabetic patients. Patients with diabetes and IDH did not make significant gains in pain and function with surgical intervention relative to diabetic patients who underwent nonoperative treatment. Diabetic patients with SpS and DS experienced significantly greater improvements in pain and function with surgical intervention when compared with nonoperative treatment. Among those who had surgery, nondiabetic patients with SpS achieved marginally significantly greater gains in function than their diabetic counterparts (SF-36 physical function, P = 0.062). Among patients who had surgery for DS, diabetic patients did not have as much improvement in pain or function as did the nondiabetic population (SF-36 bodily pain, P = 0.003; physical function, P = 0.002). Postoperative complications were more prevalent in patients with diabetes than in nondiabetic patients with SpS (P = 0.002). There was an increase in postoperative (P = 0.028) and intraoperative (P = 0.029) blood replacement in DS patients with diabetes.

Conclusion

Diabetic patients with SpS and DS benefited from surgery, though older SpS patients with diabetes have more postoperative complications. IDH patients with diabetes did not benefit from surgical intervention.

Keywords: complications, degenerative spondylolisthesis, diabetes mellitus, disability, intervertebral disc herniation, pain, spinal stenosis

Diabetes mellitus is a debilitating chronic illness that affects 16 million Americans.1 Although the disease itself is not necessarily disabling, many of its sequelae, including diabetic neuropathy and microvascular disease, can cause chronic lower extremity pain and lead to significant limitation in overall function.1-6 The coexistence of diabetic and lumbar spine disease may cause even greater limitation among the diabetic population when compared with nondiabetic population, prompting more aggressive treatment.

The literature contains conflicting reports regarding the benefits of surgical decompression and fusion among diabetic patients with lumbar spinal stenosis (SpS) and degenerative disc disease.7-11 In addition, it has been suggested that patients with diabetes may be predisposed to complications, such as infection, prolonged hospitalization, longer operative time, and higher nonunion rate, after spinal surgery.11-15 After surgical intervention, patients with diabetes may also have poor health status and decreased life expectancy compared with nondiabetic patients.16-18

This study compares the baseline characteristics of patients with diabetes to the nondiabetic patients in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT). The study also evaluates the impact of the diabetic condition on the clinical outcomes of operative and nonoperative treatment.19-23

MATERIALS AND METHODS

SPORT enrolled patients from 2000 to 2005 at 13 sites in 11 US states. Subjects were enrolled in both observational and randomized cohorts for all diagnoses. Patients chose whether or not they were willing to be randomized. If they were, they were enrolled in the randomized cohort. If they were not, they were enrolled in the observational cohort. Once in the randomized cohort, they were randomized to surgery or nonoperative treatment. Once in the observational cohort, they elected to have surgery or nonoperative treatment. The primary outcome measures were the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) Health Status questionnaire subscores for bodily pain (BP) and physical function (PF),24,25 as well as low back pain-associated disability as measured by the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI).26 Baseline characteristics analyzed in this study included age, sex, race, income, work status, disability status, medical comorbidities, mean body mass index (BMI), smoking, and health status, as measured by SF-36. Further details about the SPORT study have been previously published.19-23,27

There are a total of 2505 patients enrolled in the observational and randomized cohorts of the SPORT trial, 2406 of whom provided information regarding diabetic status. The cohorts were combined after analyzing each separately and testing for differences in effect sizes between RCT and OBS cohorts. Since no differences were seen, the cohorts were combined for as-treated analyses. This was done in several previous SPORT secondary analysis articles,28-30 and a detailed statistical rationale for this strategy has been published.31

Baseline characteristics for all patients for whom follow-up and diabetes status were available were compiled and comparisons made between diabetic patients and nondiabetic patients (Table 1). All 2505 enrolled patients completed a baseline survey. If a patient completed a baseline survey, they might have missing values for those questions they refused to answer. Therefore, the number of patients varied with each baseline characteristic. These numbers, along with the total number of patients included in the analysis, are included in Table 1. No patients were missing age. Only patients who had both baseline and at least one follow-up were included in the analyses. Only two patients were missing BMI; they both were in the intervertebral disc herniation (IDH), nondiabetic group. Further, the diabetic and nondiabetic groups were stratified by diagnosis (IDH, SpS, and degenerative spondylolisthesis [DS]).

Table 1. Patient Baseline Demographic Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Health Status Measures.

| All Analyzed Patients (IDH + SpS + DS) |

IDH | SpS | DS | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Not Diabetic, n = 2207 |

Diabetic, n = 199 |

P † | Not Diabetic, n = 1145 |

Diabetic, n = 40 |

P † | Not Diabetic, n = 538 |

Diabetic, n = 89 |

P † | Not Diabetic, n = 524 |

Diabetic, n = 70 |

P † |

| Age, yr; mean (SD) | 52.8 (16.3) | 63.9 (11.9) | <0.001 | 41.5 (11.3) | 50.4 (11.8) | <0.001 | 64.3 (12) | 67.2 (9.3) | 0.028 | 65.9 (10.4) | 67.3 (9.1) | 0.28 |

| Female, n (%) | 1061 (48) | 99 (50) | 0.70 | 488 (43) | 17 (42) | 0.88 | 211 (39) | 37 (42) | 0.76 | 362 (69) | 45 (64) | 0.50 |

| Ethnicity, not Hispanic, n (%)‡ |

2117 (96) | 193 (97) | 0.59 | 1094 (96) | 37 (92) | 0.60 | 512 (95) | 87 (98) | 0.41 | 511 (98) | 69 (99) | 0.90 |

| Race, white, n (%)‡ | 1900 (86) | 153 (77) | <0.001 | 995 (87) | 31 (78) | 0.14 | 459 (85) | 69 (78) | 0.087 | 446 (85) | 53 (76) | 0.066 |

| Education, at least some college; n (%) |

1548 (70) | 121 (61) | 0.008 | 852 (74) | 26 (65) | 0.25 | 343 (64) | 54 (61) | 0.66 | 353 (67) | 41 (59) | 0.18 |

| Income, <$50,000; n (%) |

740 (34) | 51 (26) | 0.028 | 513 (45) | 19 (48) | 0.86 | 107 (20) | 15 (17) | 0.60 | 120 (23) | 17 (24) | 0.91 |

| Marital Status, married; n (%) |

1525 (69) | 140 (70) | 0.77 | 799 (70) | 31 (78) | 0.38 | 381 (71) | 62 (70) | 0.92 | 345 (66) | 47 (67) | 0.93 |

| Work status, n (%) | <0.001 | 0.23 | 0.009 | 0.043 | ||||||||

| Full- or part-time | 1051 (48) | 52 (26) | 697 (61) | 19 (48) | 179 (33) | 18 (20) | 175 (33) | 15 (21) | ||||

| Disabled | 234 (11) | 31 (16) | 151 (13) | 7 (18) | 43 (8) | 14 (16) | 40 (8) | 10 (14) | ||||

| Other | 921 (42) | 116 (58) | 296 (26) | 14 (35) | 316 (59) | 57 (64) | 309 (59) | 45 (64) | ||||

| Compensation, n (%)§ | 275 (12) | 18 (9) | 0.19 | 202 (18) | 4 (10) | 0.30 | 37 (7) | 10 (11) | 0.22 | 36 (7) | 4 (6) | 0.91 |

| Body mass index; mean (SD)¶ |

28.3 (5.6) | 32.9 (6.3) | <0.001 | 27.8 (5.4) | 32.2 (7.3) | <0.001 | 29 (5.3) | 32.9 (6.3) | <0.001 | 28.7 (6) | 33.2 (5.9) | <0.001 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 375 (17) | 20 (10) | 0.015 | 275 (24) | 7 (18) | 0.45 | 53 (10) | 9 (10) | 0.91 | 47 (9) | 4 (6) | 0.49 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Hypertension | 598 (27) | 128 (64) | <0.001 | 143 (12) | 20 (50) | <0.001 | 233 (43) | 55 (62) | 0.002 | 222 (42) | 53 (76) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 25 (1) | 11 (6) | <0.001 | 3 (0) | 2 (5) | <0.001 | 11 (2) | 2 (2) | 0.78 | 11 (2) | 7 (10) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 25 (1) | 199 (100) | <0.001 | 8 (1) | 40 (100) | <0.001 | 7 (1) | 89 (100) | <0.001 | 10 (2) | 70 (100) | <0.001 |

| Osteoporosis | 132 (6) | 15 (8) | 0.47 | 16 (1) | 2 (5) | 0.24 | 52 (10) | 8 (9) | 0.99 | 64 (12) | 5 (7) | 0.30 |

| Cancer | 101 (5) | 17 (9) | 0.021 | 21 (2) | 3 (8) | 0.054 | 40 (7) | 8 (9) | 0.77 | 40 (8) | 6 (9) | 0.97 |

| Depression | 279 (13) | 30 (15) | 0.38 | 137 (12) | 4 (10) | 0.90 | 61 (11) | 9 (10) | 0.87 | 81 (15) | 17 (24) | 0.09 |

| Anxiety | 125 (6) | 12 (6) | 0.96 | 76 (7) | 0 (0) | 0.18 | 23 (4) | 7 (8) | 0.23 | 26 (5) | 5 (7) | 0.63 |

| Drug dependency | 10 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.71 | 6 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.50 | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.66 | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.56 |

| Heart problem | 289 (13) | 59 (30) | <0.001 | 57 (5) | 4 (10) | 0.29 | 136 (25) | 29 (33) | 0.19 | 96 (18) | 26 (37) | <0.001 |

| Lung problem | 117 (5) | 20 (10) | 0.009 | 44 (4) | 0 (0) | 0.40 | 39 (7) | 9 (10) | 0.47 | 34 (6) | 11 (16) | 0.012 |

| Stomach problem | 364 (16) | 50 (25) | 0.003 | 135 (12) | 7 (18) | 0.40 | 115 (21) | 24 (27) | 0.30 | 114 (22) | 19 (27) | 0.39 |

| Bowel or intestinal problem |

185 (8) | 24 (12) | 0.10 | 75 (7) | 5 (12) | 0.25 | 71 (13) | 15 (17) | 0.45 | 39 (7) | 4 (6) | 0.78 |

| Liver problem | 28 (1) | 3 (2) | 0.97 | 13 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.92 | 9 (2) | 1 (1) | 0.94 | 6 (1) | 2 (3) | 0.54 |

| Kidney problem | 69 (3) | 15 (8) | 0.002 | 26 (2) | 2 (5) | 0.56 | 26 (5) | 3 (3) | 0.74 | 17 (3) | 10 (14) | <0.001 |

| Blood vessel problem | 79 (4) | 13 (7) | 0.059 | 15 (1) | 1 (2) | 0.96 | 31 (6) | 7 (8) | 0.60 | 33 (6) | 5 (7) | 0.99 |

| Nervous system problem |

46 (2) | 7 (4) | 0.29 | 18 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.89 | 10 (2) | 3 (3) | 0.60 | 18 (3) | 4 (6) | 0.54 |

| Joint problem | 801 (36) | 110 (55) | <0.001 | 212 (19) | 9 (22) | 0.67 | 292 (54) | 54 (61) | 0.31 | 297 (57) | 47 (67) | 0.12 |

| Other** | 696 (32) | 83 (42) | 0.004 | 486 (42) | 40 (100) | <0.001 | 186 (35) | 34 (38) | 0.59 | 200 (38) | 34 (49) | 0.12 |

| SF-36 scores, mean (SD)†† |

||||||||||||

| Bodily pain | 30.2 (20) | 32.4 (20.3) | 0.13 | 27.1 (20.1) | 29.6 (20.2) | 0.43 | 33.3 (20) | 35.2 (18.3) | 0.40 | 33.7 (18.6) | 30.4 (22.4) | 0.17 |

| Physical functioning | 36.8 (24.5) | 29.3 (20.5) | <0.001 | 37.9 (25.5) | 33.9 (25.2) | 0.33 | 35.7 (24) | 30.3 (17.9) | 0.043 | 35.6 (22.4) | 25.3 (20.1) | <0.001 |

| Vitality | 41 (21.1) | 37.8 (22.2) | 0.038 | 38.5 (20.1) | 36.1 (21.2) | 0.46 | 42.9 (21.8) | 41.2 (21.7) | 0.49 | 44.6 (21.8) | 34.4 (23.2) | <0.001 |

| Physical component summary |

30.3 (8.5) | 27.1 (8.2) | <0.001 | 30.6 (8.4) | 28.8 (9.1) | 0.18 | 30.1 (8.8) | 27.2 (7.4) | 0.003 | 30 (8.2) | 26 (8.7) | <0.001 |

| Mental component summary |

47.4 (11.8) | 48.7 (12.3) | 0.13 | 45.1 (11.6) | 45.6 (11) | 0.79 | 49.2 (11.9) | 51.1 (11.6) | 0.17 | 50.4 (11.2) | 47.5 (13.4) | 0.043 |

| Oswestry Disability Index; mean (SD)‡‡ |

45.6 (20.2) | 46.2 (19.2) | 0.66 | 49.4 (21.3) | 50.7 (21.9) | 0.70 | 41.9 (18.8) | 44.6 (16.6) | 0.19 | 41 (17.4) | 45.6 (20.5) | 0.041 |

| Sciatica Frequency Index (0–24); mean (SD)§§ |

14.9 (5.6) | 14.5 (5.9) | 0.28 | 15.9 (5.4) | 15.6 (5.3) | 0.79 | 14 (5.7) | 13.1 (6) | 0.18 | 13.8 (5.5) | 15.5 (5.7) | 0.013 |

| Sciatica Bothersome Index (0–24); mean (SD)§§ |

15.1 (5.5) | 14.6 (5.9) | 0.25 | 15.6 (5.3) | 14.8 (5.2) | 0.35 | 14.5 (5.7) | 13.5 (6) | 0.16 | 14.5 (5.5) | 15.8 (6) | 0.076 |

| Back Pain Bothersomeness (0–6); mean (SD)¶¶ |

4 (1.8) | 4.3 (1.8) | 0.035 | 3.9 (1.9) | 3.9 (2) | 0.89 | 4.1 (1.8) | 4.1 (1.8) | 0.73 | 4.2 (1.8) | 4.8 (1.7) | 0.014 |

| Very dissatisfied with symptoms, n (%) |

1656 (75) | 132 (66) | 0.009 | 920 (80) | 28 (70) | 0.16 | 374 (70) | 54 (61) | 0.12 | 362 (69) | 50 (71) | 0.79 |

| Patient self-assessed health trend, n (%) |

0.014 | 0.57 | 0.80 | 0.69 | ||||||||

| Getting better | 249 (11) | 14 (7) | 173 (15) | 6 (15) | 41 (8) | 5 (6) | 35 (7) | 3 (4) | ||||

| Staying about the same |

864 (39) | 66 (33) | 518 (45) | 15 (38) | 174 (32) | 29 (33) | 172 (33) | 22 (31) | ||||

| Getting worse | 1092 (49) | 119 (60) | 453 (40) | 19 (48) | 323 (60) | 55 (62) | 316 (60) | 45 (64) | ||||

| Treatment preference at baseline, n (%) |

0.21 | 0.80 | 0.37 | 0.99 | ||||||||

| Preference for nonsurgery |

772 (35) | 80 (40) | 378 (33) | 15 (38) | 190 (35) | 38 (43) | 204 (39) | 27 (39) | ||||

| Not sure | 415 (19) | 40 (20) | 190 (17) | 7 (18) | 104 (19) | 17 (19) | 121 (23) | 16 (23) | ||||

| Preference for surgery | 1015 (46) | 79 (40) | 574 (50) | 18 (45) | 243 (45) | 34 (38) | 198 (38) | 27 (39) | ||||

Patients who report being told by their doctor that they have diabetes and also report that they are currently receiving treatment for diabetes.

P values are from χ2 test for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables.

Race or ethnic group was self-assessed. Whites and blacks could be either Hispanic or non-Hispanic.

This category includes patients who were receiving or had applications pending for workers compensation, social security compensation, or other compensation.

The body mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Other indicates problems related to stroke, diabetes, osteoporosis, cancer, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol, drug depen dence, heart, lung, liver, kidney, blood vessel, nervous system, hypertension, migraine, anxiety, stomach or bowel for IDH cohort and stroke, cancer, lung, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol, drug dependency, liver, kidney, blood vessel, nervous system, migraine, anxiety for SPS or DS cohort.

The SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score indicating less-severe symptoms.

The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less-severe symptoms.

The Sciatica Bothersomeness index range from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less-severe symptoms.

¶¶The Low Back Pain Bothersomeness Scale ranges from 0 to 6, with lower scores indicating less-severe symptoms

DS indicates degenerative spondylolisthesis; IDH, intervertebral disk herniation; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; SpS, spinal stenosis.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Baseline characteristics between patients with diabetes and patients without diabetes were compared by using a χ2 test for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. Outcome analyses were performed, as they were in the primary SPORT articles for the individual diagnoses.19-21,27 Outcomes were analyzed by using longitudinal mixed-effects models, with a random individual effect to account for the correlation among repeated observations within individuals over time. Adjusting covariates found to predict missing data, treatment received, and outcome were included in the model (further details described previously).19-21,23,27 In addition, outcome, center, age, and sex were included in all longitudinal outcome models. All analyses were as-treated, and treatment is considered a time-varying covariate. Therefore, patients were categorized at each time-point as to whether or not they received surgical treatment; follow-up times were measured from the beginning of treatment, and baseline covariates were updated at the time of surgery. All observations before surgery were considered in the nonoperative estimate, with follow-up time measured from enrollment; all observations after surgery contributed to the surgical estimate, with follow-up time measured from the time of surgery. Rates of repeated surgery at 1, 2, 3, and 4 years were estimated via Kaplan-Meier curves. P values were calculated with the use of the log-rank test. Secondary and binary outcomes were analyzed by using generalized estimating equations, assuming a compound symmetry working correlation structure. Comparisons in outcomes between patients with diabetes and patients without diabetes are made at each time-point with multiple degree-of-freedom Wald tests. Across the 4-year follow-up, overall comparisons of area under the curve were made by using a Wald test. Throughout the text, we have distinguished between these by using the terms “at XX time” versus “across 4 years.” Analyses were performed with the SAS PROC MIXED and PROC GENMOD procedures (SAS version 9.2, Windows ZP Pro, Cary, NC). Statistical significance is defined as P < 0.05 based on a two-sided hypothesis, with no adjustment made for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Information about follow-up outcomes and diabetic status was available for 2406 patients who were included in the analysis (Table 1). Please note that we here discuss only those differences that pertain to diabetes; those significant differences that remain have been reported and discussed in previous SPORT articles.

One hundred ninety-nine patients reported being treated for diabetes having been told that they had diabetes by their physician. The mean age of the patients with diabetes (63.9 years) was significantly greater than that of the nondiabetic patients (52.8 years) (P < 0.001). A significantly higher percentage of patients with diabetes were nonwhites (23% vs. 14%, P < 0.001). Patients with diabetes had a significantly higher mean BMI than nondiabetic patients (32.9 vs. 28.3, P < 0.001). Several medical conditions were significantly more common among diabetic patients, including hypertension (64% vs. 27%, P < 0.001), stroke (6% vs. 1%, P < 0.001), cardiac conditions (30% vs. 13%, P < 0.001), and “joint” problems (55% vs. 36%, P < 0.001). There was also a significantly higher incidence of lung cancer and stomach problems among patients with diabetes. Vascular problems were more prevalent in patients with diabetes.

Significantly, more nondiabetic patients were working (48%) than were the patients with diabetes (26%), and more patients with diabetes were disabled (16%) than nondiabetic patients (11%). Among the SF-36 subscales, there were significant differences between the groups at baseline with respect to the physical component summary (PCS) score (27.1 among patients with diabetes vs. 30.3 for nondiabetic patients, P < 0.001) and for the PF score (29.3 for patients with diabetes vs. 36.8 for nondiabetic patients, P < 0.001). The impact of low back pain on a patient’s daily function, as measured by the ODI, was not different for the two groups (P = 0.66).

INTERVERTEBRAL DISC HERNIATION

In the 1185 patients with IDH, only 40 IDH patients (3.4%) were diabetic (Table 1). These patients were significantly older than the nondiabetic population (mean age, 50.4 years vs. 41.5 years). Patients with diabetes had a significantly higher BMI (P < 0.001) and a significantly higher incidence of hypertension and stroke (P < 0.001 for both). Fewer IDH patients with diabetes than nondiabetic patients were working, but this was not statistically significant (48% vs. 61%, P = 0.23). There were no significant differences in SF-36 or ODI scores between the patients with diabetes and patients without diabetes.

Operative treatments, complications, and events were reviewed for the IDH subgroup (Table 2). After surgery, there was one nerve-root injury among patients without diabetes and none among those with diabetes (P = 0.006). There was no difference in infection or wound dehiscence. There were no differences in operation time, blood loss or replacement, the length of stay, postoperative mortality, or additional surgeries for IDH patients.

TABLE 2. Operative Treatments, Complications, and Events.

| IDH | SpS | DS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Diabetic, n = 768* | Diabetic, n = 24* | P | Not Diabetic, n = 351* | Diabetic, n = 53* | P | Not Diabetic, n = 345* | Diabetic, n = 40* | p | |

| Specific procedures, n (%)† | 0.73 | 0.33 | |||||||

| Decompression only | NA | NA | NA | 301 (88) | 47 (90) | 21 (6) | 1 (2) | ||

| Noninstrumented fusion | NA | NA | NA | 19 (6) | 3 (6) | 74 (22) | 6 (15) | ||

| Instrumented fusion | NA | NA | NA | 23 (7) | 2 (4) | 243 (72) | 33 (82) | ||

| Multi-level fusion | NA | NA | NA | 14 (4) | 2 (4) | 0.76 | 79 (23) | 10 (25) | 0.92 |

| Discectomy/decompression level, n (%)‡ | |||||||||

| L2–L3 | 14 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.91 | 124 (36) | 21 (40) | 0.65 | 35 (10) | 9 (23) | 0.039 |

| L3–4 | 27 (4) | 0 (0) | 0.71 | 239 (69) | 37 (71) | 0.93 | 168 (50) | 19 (49) | 0.97 |

| L4–L5 | 297 (39) | 14 (58) | 0.093 | 315 (92) | 51 (98) | 0.17 | 331 (97) | 39 (100) | 0.53 |

| L5–S1 | 438 (58) | 11 (46) | 0.34 | 135 (39) | 17 (33) | 0.45 | 104 (31) | 9 (23) | 0.43 |

| Levels decompressed, n (%) | 0.97 | 0.42 | |||||||

| None | NA | NA | NA | 7 (2) | 1 (2) | 3 (1) | 1 (2) | ||

| 1 | NA | NA | NA | 80 (23) | 12 (23) | 141 (41) | 16 (40) | ||

| 2 | NA | NA | NA | 110 (31) | 15 (28) | 126 (37) | 11 (28) | ||

| 3 + | NA | NA | NA | 154 (44) | 25 (47) | 75 (22) | 12 (30) | ||

| Operation time, min; mean (SD) | 76.4 (37.4) | 88 (37.9) | 0.14 | 127.3 (64.5) | 140.3 (73.2) | 0.19 | 205.7 (83.6) | 216.8 (83.4) | 0.43 |

| Blood loss, mL; mean (SD) | 63.8 (102.9) | 90.1 (72.1) | 0.22 | 299.5 (396.4) | 373.6 (436.9) | 0.21 | 571.6 (461.8) | 688.4 (527.1) | 0.14 |

| Blood Replacement, n (%) | |||||||||

| Intraoperative replacement | 6 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.45 | 32 (9) | 7 (13) | 0.52 | 111 (32) | 20 (51) | 0.029 |

| Postoperative transfusion | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 15 (4) | 5 (9) | 0.21 | 66 (19) | 14 (36) | 0.028 | |

| Length of hospital stay, d; mean (SD) | 0.97 (1) | 1.1 (0.8) | 0.55 | 3.1 (2.2) | 3.8 (3.6) | 0.051 | 5.7 (20.1) | 5.1 (2.2) | 0.83 |

| Intraoperative complications, n (%)§ | |||||||||

| Dural tear/spinal fluid leak | 23 (3) | 1 (4) | 0.78 | 32 (9) | 5 (9) | 0.85 | 38 (11) | 2 (5) | 0.36 |

| Vascular injury | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0.19 | ||

| Nerve root injury | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.07 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Other | 3 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.17 | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.86 | 6 (2) | 3 (8) | 0.084 |

| None | 741 (96) | 23 (96) | 0.70 | 314 (90) | 48 (91) | 0.91 | 302 (88) | 35 (88) | 0.81 |

| Postoperative complications/events, n (%)¶ | |||||||||

| Never-root injury | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.006 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.19 | |

| Wound dehiscence | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.19 | ||

| Wound hematoma | 4 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.27 | 2 (1) | 2 (4) | 0.15 | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0.19 |

| Wound infection | 17 (2) | 1 (4) | 0.95 | 6 (2) | 3 (6) | 0.20 | 11 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.53 |

| Other | 26 (3) | 1 (4) | 0.71 | 15 (4) | 7 (13) | 0.021 | 32 (9) | 4 (10) | 0.91 |

| None | 719 (94) | 22 (92) | 0.95 | 310 (90) | 39 (74) | 0.002 | 242 (71) | 22 (56) | 0.092 |

| Postoperative mortality, n (%) | |||||||||

| Death within 6 wk of surgery | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0.31 | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0.21 | |

| Death within 3 mo of surgery | 1 (0.1)†† | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0.31 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (2.3) | 0.53 | |

| Additional surgeries, n (%)‡‡ | |||||||||

| 1-yr rate | 43 (6) | 3 (12) | 0.13 | 20 (6) | 2 (4) | 0.51 | 23 (7) | 3 (7) | 0.83 |

| 2-yr rate | 58 (7) | 4 (17) | 0.08 | 30 (8) | 2 (4) | 0.22 | 42 (12) | 7 (17) | 0.36 |

| 3-yr rate | 65 (8) | 4 (17) | 0.13 | 42 (12) | 4 (7) | 0.31 | 47 (13) | 8 (20) | 0.30 |

| 4-yr rate | 76 (10) | 4 (17) | 0.23 | 47 (13) | 6 (11) | 0.60 | 49 (14) | 10 (24) | 0.09 |

| Recurrent disc herniation, n (%) | 45 (6) | 4 (17) | NA | N/A | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Recurrent stenosis/progressive listhesis, n (%) | NA | NA | NA | 19 (6) | 4 (8) | 16 (5) | 3 (8) | ||

| Pseudarthrosis/fusion exploration, | NA | NA | NA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.9) | 1 | ||

| Complication or other, n (%) | 21 (3) | 0 | 17 (4.9) | 1 | 22 (6.5) | 3 (7.7) | |||

| New condition, n (%) | 9 (1) | 0 | 7 (2) | 1 | 8 (2.4) | 1 | |||

Surgical information was available for 768 IDH patients without diabetes and 24 IDH patients with diabetes, 351 SpS patients without diabetes and 53 SpS patients with diabetes, and 345 DS patients without diabetes and 40 DS patients with diabetes.

Specific procedure data was available for 343 SpS patients without diabetes and 52 SpS patients with diabetes, and 338 DS patients without diabetes and 40 DS patients with diabetes.

In IDH patients, discectomy level is recorded, and in DS and SpS patients, decompression level is recorded.

No cases were reported of aspiration into the respiratory tract or operation at wrong level.

Complications or events occurring up to 8 wk after surgery are listed. There were no reported cases of bone-graft complication, cerebrospinal fluid leak, paralysis, cauda equina injury, and pseudarthrosis.

Patient died after heart surgery at another hospital, the death was judged unrelated to spine surgery.

Rates of repeated surgery at 1, 2, 3, and 4 yr are Kaplan-Meier estimates. P values were calculated with the use of the log-rank test. Numbers and percentages are based on the first additional surgery if more than one additional surgery.

DS indicates degenerative spondylolisthesis; IDH, intervertebral disk herniation; SpS, spinal stenosis.

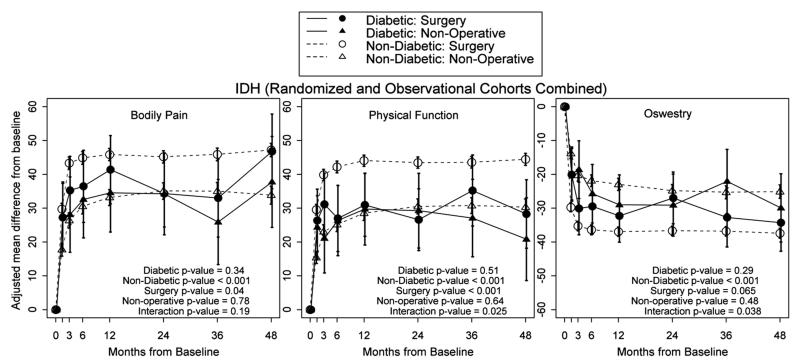

In the IDH cohort, the nondiabetic group had significantly greater improvement (P < 0.001) with surgery when compared with nonoperative treatment in BP, PF, and ODI at 4 years (Figure 1). For all patients who had surgery, nondiabetic patients had significantly greater improvement than patients with diabetes in BP (P < 0.04) and PF (P < 0.001). Patients with diabetes did not have significant improvement with surgery versus nonoperative treatment for BP, PF, or ODI. Outcomes for nonoperative treatment were not different between patients with diabetes and patients without diabetes for BP (P = 0.78), PF (P = 0.64), or ODI (P = 0.48).

Figure 1.

At 4 years, among those who had surgery, there was a significantly higher proportion of nondiabetic patients who were working compared with the diabetic group (P = 0.019) (Table 3).

TABLE 3. Subgroup Results from Adjusted* As-Treated Outcome Analysis by Diabetes for the Randomized and Observational Cohorts Combined Patients with Lumbar Intervertebral Disk Herniation.

| Outcome | 1-Yr | 2-Yr | 3-Yr | 4-Yr | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDH (RCT & OBS) | Diabetes | Surgical | Nonoperative | Treatment Effect,† OR (95% CI) |

Surgical | Nonoperative | Treatment Effect,† OR (95% CI) |

Surgical | Nonoperative | Treatment Effect,† OR (95% CI) |

Surgical | Nonoperative | Treatment Effect,† OR (95% CI) |

| Primary outcomes | |||||||||||||

| SF-36 bodily pain (0–100), mean (SE) |

Not diabetic | 45.9 (0.9) | 33.1 (1.2) | 12.7 (9.9 to 15.5) | 45.2 (0.9) | 35.1 (1.2) | 10.1 (7.2 to 13) | 45.9 (1) | 35 (1.3) | 10.9 (7.8 to 13.9) | 47.2 (1) | 33.9 (1.4) | 13.3 (10.2 to 16.5) |

| Diabetic‡ | 41.4 (5.1) | 34.5 (5.9) | 6.8 (−7.7 to 21.3) | 34.3 (5.1) | 34.2 (6.2) | 0.1 (−14.6 to 14.8) | 33 (5.9) | 25.9 (6.4) | 7.1 (−9.2 to 23.4) | 46.8 (5.6) | 37.7 (6.9) | 9.1 (−7.6 to 25.7 | |

| P § | 0.39 | 0.82 | 0.43 | 0.035 | 0.89 | 0.19 | 0.031 | 0.16 | 0.66 | 0.95 | 0.58 | 0.62 | |

| SF-36 physical function (0–100), mean (SE) |

Not diabetic | 44 (0.8) | 28.5 (1.1) | 15.5 (13 to 18.1) | 43.5 (0.8) | 30.5 (1.1) | 13 (10.4 to 15.6) | 43.5 (0.9) | 30.8 (1.2) | 12.8 (10.1 to 15.5) | 44.4 (0.9) | 30.3 (1.2) | 14.1 (11.3 to 17) |

| Diabetic | 31 (4.7) | 29.7 (5.4) | 1.2 (−11.9 to 14.4) | 26.6 (4.7) | 29.2 (5.6) | −2.7 (−16 to 10.7) | 35.2 (5.4) | 27.1 (5.9) | 8.1 (−6.6 to 22.8) | 28.3 (5.2) | 20.8 (6.2) | 7.4 (−7.6 to 22.5) | |

| P | 0.007 | 0.83 | 0.036 | <0.001 | 0.83 | 0.024 | 0.13 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.002 | 0.13 | 0.39 | |

| Mental component summary (0–100), mean SE) |

Not diabetic | 7.6 (0.4) | 4.4 (0.5) | 3.2 (2.1 to 4.3) | 6.4 (0.4) | 4.4 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.8 to 3.1) | 6.3 (0.4) | 4.1 (0.5) | 2.2 (1 to 3.4) | 6 (0.4) | 4.5 (0.5) | 1.5 (0.2 to 2.8) |

| Diabetic | 6.8 (2.1) | 2 (2.4) | 4.8 (−1 to 10.6) | 6.1 (2.1) | 6.4 (2.5) | −0.3 (−6.2 to 5.7) | 3.9 (2.4) | 5.1 (2.6) | −1.3 (−7.8 to 5.3) | 6.2 (2.3) | 2.2 (2.9) | 4 (−3 to 10.9) | |

| P | 0.70 | 0.32 | 0.60 | 0.89 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.31 | 0.70 | 0.31 | 0.94 | 0.42 | 0.49 | |

| Oswestry Disability Index (0–100), mean (SE) |

Not diabetic | −37 (0.7) | −23 (0.9) | −14 (−16.1 to −11.9) | −36.7 (0.7) | −24.8 (0.9) | −11.9 (−14 to −9.7) | −36.8 (0.7) | −25.3 (1) | −11.5 (−13.8 to −9.3) | −37.4 (0.8) | −25.1 (1) | −12.3 (−14.7 to −10) |

| Diabetic | −32.3 (4) | −29 (4.5) | −3.3 (−14 to 7.5) | −27 (3.9) | −29.1 (4.7) | 2.1 (−8.8 to 13) | −32.8 (4.5) | −22.1 (4.9) | −10.6 (−22.6 to 1.3) | −34.3 (4.3) | −29.9 (5.1) | −4.4 (−16.6 to 7.8) | |

| P | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.054 | 0.015 | 0.37 | 0.013 | 0.37 | 0.52 | 0.89 | 0.48 | 0.36 | 0.21 | |

| Very/somewhat satisfied with symptoms (%) |

Not diabetic | 71.5 | 46.3 | 25.3 (19.2 to 31.3) | 72.4 | 52.7 | 19.7 (13.5 to 25.8) | 71.6 | 52.8 | 18.8 (12.3 to 25.4) | 73.5 | 50 | 23.4 (16.6 to 30.3) |

| Diabetic | 70.2 | 59.8 | 10.4 (−19.7 to 40.5) | 65.8 | 30.8 | 35 (5,65) | 64.1 | 50.7 | 13.4 (−22.5 to 49.3) | 85.1 | 61.6 | 23.5 (−8.5 to 55.5) | |

| P | 0.89 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.53 | 0.18 | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.89 | 0.76 | 0.32 | 0.41 | 0.79 | |

| Very/somewhat satisfied with care (%) |

Not diabetic | 92.4 | 83.7 | 8.8 (4.4 to 13.1) | 90.7 | 80.1 | 10.6 (5.8 to 15.4) | 88.6 | 75.1 | 13.5 (8 to 19) | 90.5 | 77.9 | 12.6 (7 to 18.3) |

| Diabetic | 80.5 | 76 | 4.5 (−21.5 to 30.5) | 85.3 | 66 | 19.3 (−8.8 to 47.4) | 93.7 | 81.6 | 12.1 (−11.9 to 36.1) | 80.4 | 82.8 | −2.3 (−30.6 to 26) | |

| P | 0.048 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.50 | 0.58 | 0.82 | 0.22 | 0.71 | 0.29 | |

| Self-rated progress, major improvement (%) |

Not diabetic | 80.2 | 56.3 | 23.9 (18.1 to 29.8) | 75.7 | 60.8 | 14.8 (8.8 to 20.9) | 73.5 | 57 | 16.4 (9.9 to 22.9) | 76.6 | 54.5 | 22 (15.2 to 28.8) |

| Diabetic | 77.4 | 70.4 | 7 (−20.6 to 34.6) | 63.2 | 65.8 | −2.6 (−33.5 to 28.3) | 62.7 | 64.3 | −1.6 (−36.2 to 33.1) | 67.6 | 65.8 | 1.9 (−32.9 to 36.6) | |

| P | 0.76 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.72 | 0.29 | 0.36 | 0.60 | 0.31 | 0.45 | 0.44 | 0.29 | |

| Work status, working (%) | Not diabetic | 79.3 | 77.4 | 1.9 (−2.9 to 6.6) | 78.7 | 78.9 | −0.2 (−5 to 4.5) | 76.4 | 74.4 | 2.1 (−3.3 to 7.4) | 77.5 | 73.2 | 4.3 (−1.4 to 9.9) |

| Diabetic | 62.1 | 69.2 | −7.1 (−34.6 to 20.3) | 57.4 | 54.3 | 3 (−27.3 to 33.4) | 72.3 | 63.8 | 8.5 (−21.4 to 38.4) | 57.8 | 70.2 | −12.5 (−44.2 to 19.3) | |

| P | 0.044 | 0.30 | 0.38 | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.81 | 0.64 | 0.30 | 0.64 | 0.019 | 0.72 | 0.094 | |

Adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, baseline score (for SF-36, ODI), and center.

Treatment effect is the difference between the surgical and nonoperative mean change from baseline. Analysis is done by using a mixed model with a random subject intercept term. Treatment is a time-varying covariate where a patients’ experience before surgery is attributed to the nonoperative arm, and time is measured from enrollment; his/her postsurgery outcomes are attributed to the surgical arm, and time is measured from the time of surgery.

Patients who report being told by their doctors that they have diabetes and also report that they are currently receiving treatment for diabetes.

P values at each time-point are from multiple degree-of-freedom Wald tests.

SPINAL STENOSIS

Of 627 patients with SpS (Table 1), 89 patients (14.2%) had diabetes. Patients with diabetes were significantly older than those without diabetes (mean age, 67 years vs. 64 years, P = 0.028). BMI was higher in patients with diabetes (P < 0.001). The patients with diabetes had a significantly higher incidence of hypertension (P = 0.002) (Table 1).

Initial ODI scores were not significantly different between the two groups, although physical functioning and physical component scores were significantly lower in patients with diabetes than in those without diabetes at baseline (P = 0.043 for PF and P = 0.003 for PCS). There was no difference in workers’ compensation between the two groups, though significantly more nondiabetic patients worked than did patients with diabetes (33% vs. 20%, P = 0.009).

Nondiabetic patients encountered significantly fewer postoperative complications than patients with diabetes, 90% versus 74% (P = 0.002) (Table 2). There were more infections among the patients with diabetes (6%) than among the nondiabetic patients (2%), but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.20). Postoperative complications included wound infection and hematoma, headaches, nausea and vomiting, anemia, postoperative hypoxia and confusion, urinary retention, and prolonged drainage. There was no significant difference in operation time, blood loss, blood replacement, or additional surgeries, or postoperative mortalities.

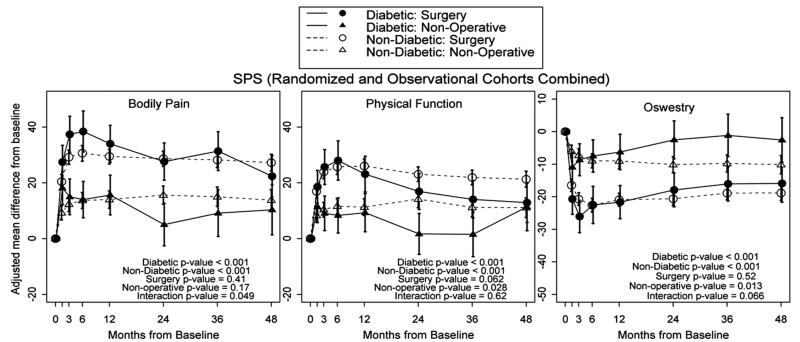

Across 4 years, SpS patients without diabetes made significant gains, with surgery relative to nonoperative care in BP (P < 0.001), PF (P < 0.001), and ODI (P < 0.001) (Figure 2). There was no significant difference in improvement with surgery between patients without diabetes and patients with diabetes for BP (P = 0.41) or ODI (P = 0.52). Nondiabetic patients who underwent surgery improved marginally more in PF (P = 0.062) relative to patients with diabetes. The patients with diabetes also did make significant gains, with surgery relative to nonoperative care in BP (P < 0.001), PF (P < 0.001), and ODI (P < 0.001). Nondiabetic patients had significantly greater improvement with nonoperative care than patients with diabetes in PF (P = 0.028) and ODI (P = 0.013) but not with BP (P = 0.17).

Figure 2.

DEGENERATIVE SPONDYLOLISTHESIS

There were 594 patients with DS, of which, 70 patients (11.8%) had diabetes (Table 1). Patients with diabetes were not significantly older than nondiabetic patients; (mean age, 67 years vs. 66 years, P = 0.28). BMI was higher in patients with diabetes (P < 0.001). Significant comorbidities, including hypertension (P < 0.001), stroke (P = 0.001), heart (P < 0.001), lung (P = 0.012), and kidney disease (P < 0.001), were significantly more common among patients with diabetes (Table 1).

Patients with diabetes worked less than nondiabetic patients (P = 0.043), though there was no significant difference in worker’s compensation. Patients with diabetes had significantly lower function according to their SF-36 scores for PF (P < 0.001), vitality (P < 0.001), and PCS (P < 0.001) The ODI score (P = 0.041) was also significantly worse in patients with diabetes (Table 1).

Blood replacement was greater in patients with diabetes both intraoperatively and after surgery (P = 0.029 and P = 0.028). There were no significant differences in intraoperative or postoperative complications (Table 2).

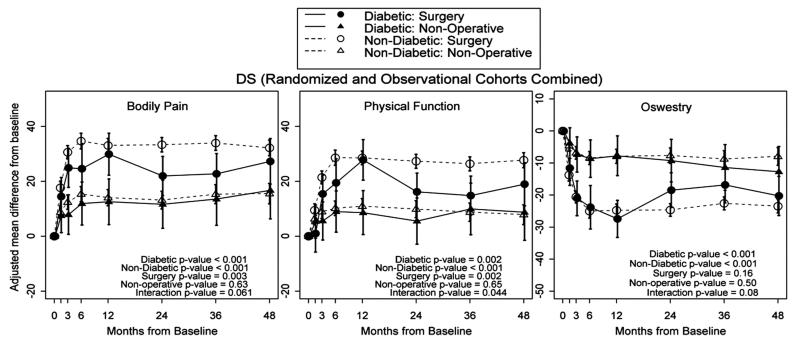

Across 4 years, nondiabetic DS patients who underwent surgery experienced significantly greater improvement in ODI (P < 0.001), BP (P < 0.001), and PF (P < 0.001) than for nonsurgical treatments (Figure 3). Nondiabetic patients who had surgery made significantly greater gains than patients with diabetes who had surgery with regard to BP (P = 0.003) and PF (P = 0.002). However, diabetic patients with DS who underwent surgery had significantly better results than those treated nonoperatively for BP (P < 0.001), PF (P < 0.002), and the ODI (P < 0.001). In contrast to surgical outcomes, the outcomes of nonoperative treatment were not significantly different between patients with diabetes and patients without diabetes.

Figure 3.

DISCUSSION

An understanding of the baseline differences between diabetic patients and nondiabetic patients in the SPORT trial may help to explain the larger treatment effects seen for nondiabetic patients across diagnostic groups, as well as the dichotomy in surgical outcomes between the diabetic patients with IDH and those with SpS and DS. In this study, patients with diabetes were significantly older than nondiabetic patients with IDH and SpS. The average age of nondiabetic patients was 53 years, while patients with diabetes averaged 64 years old. Of the subgroups, IDH had the largest difference in age (50.4 years, diabetic patients vs. 41.5 years, nondiabetic patients). Diabetic patients with SpS and DS were only slightly older (67 years) than the nondiabetic patients (SpS, 64 years and DS, 66 years).

Among patients with diabetes in the SPORT population, there were lower mean baseline PF and vitality scores. Patients with diabetes had lower baseline PCS scores and worked less than nondiabetic patients. Surprisingly, there was no difference in pain levels between patients with diabetes and patients without diabetes, suggesting that pain may not be the reason for the lower functional level of the diabetic patients. Alternatively, the difference may be secondary to the older age, obesity, and greater frequency of comorbid conditions among the patients with diabetes.32

Simpson et al11 compared lumbar spine surgical outcomes between patients with diabetes and patients without diabetes. They retrospectively reviewed the outcomes of 62 age- and sex-matched patients with and without diabetes and combined subpopulations of lumbar disc disease and SpS. The authors found poorer clinical outcomes, more infection, and longer hospitalizations among patients with diabetes. The poorer outcomes observed in patients with diabetes who underwent surgery in the study by Simpson et al11 are consistent with the findings seen in the present study in the IDH population but not with the positive outcomes that were seen in the SpS population. The study of Simpson et al,11 differs from our study in several important respects. It was retrospective in nature and combined patients with different spinal disorders. The average age of the all patients in their study was 63 years, whereas in the SPORT population, the nondiabetic patients averaged 52.8 years and the diabetic patients averaged 63.9 years. The older age of the patients might account for the increased infection rate in patients in the study by Simpson et al,11 which was not seen in the diabetic patients with IDH or SPS who underwent surgery in SPORT. The study by Simpson et al11 also used a modified outcome measure for cervical discectomy proposed by Odom, while our study relied on the SF-36 and the ODI to assess changes in pain and functional outcome.

Patients with diabetes are predisposed to a less-optimal outcome with surgery than are nondiabetic patients. Misdiagnosis may be an issue. Diabetic polyneuropathy and predisposition to peripheral nerve lesions may cloud the clinical picture. Vascular insufficiency is more common among patients with diabetes and may cause radiating pain with ambulation.33 Both coexistent vascular compromise and secondary peripheral neurologic pathology may also affect the ability of the nerve roots to recover from surgical decompression.34,35

Peripheral neuropathy and endurance deficits are common in persons with diabetes. The previous factors can affect strength and proprioception which predispose patients to greater risk of falls and slower walking speed.36-38 This results in lower scores on outcome measures related to PF but not necessarily for BP.

Cinotti et al10 performed a retrospective study that looked at 25 patients with and without diabetes who underwent surgery for SpS. In this population, the outcome was successful in both groups, without any significant differences. However, the nondiabetic patients in the study were older than those with diabetes (71 years vs. 68 years), and the nondiabetic patients were selected for comparison because they had a higher rate of comorbidity to match the two groups. The SPORT patients with diabetes had a higher rate of comorbidity than those without diabetes. This might account for the smaller treatment effect with surgery for patients with diabetes compared with nondiabetic patients in SPORT.

Arinzon et al8 retrospectively reviewed 257 consecutive patients and found that surgical decompression for SpS improved pain levels and basic activities of daily living in patients with diabetes, though the results were better in nondiabetic patients. The patients with diabetes were compared with an age-matched nondiabetic group that was older than the diabetic group (72 years vs. 70 years). As in SPORT, there were higher rates of postoperative complications in the diabetic population but, unlike SPORT, patient satisfaction was less than that of the nondiabetic control group. Another study by Airaksinen et al7 found that diabetes was associated with a lower ODI score after surgery for SpS, which we did not see in SPORT patients with diabetes. Our study might have different outcomes because it was prospective and used different outcome measures.

SPORT patients with spondylolisthesis showed no difference in postoperative infection rate or nonunion between the patients with diabetes and patients without diabetes. Bendo et al9 retrospectively also found that clinical results with posterior arthrodesis, as well as complications, were similar between patients with diabetes and patients without diabetes. This population included patients with IDH and SpS. There was no difference in postoperative complication rates. Glassman et al14 retrospectively looked at an age-matched population and found that insulin-dependent and non-insulin-dependent patients with diabetes had increased complications, including infections, postoperative root lesions, and blood loss. There was also an increased rate of nonunion among patients with diabetes. Browne et al12 retrospectively reviewed national inpatient data from 197,000 patients who had lumbar fusions. Diabetes was found to be associated with increased risk for postoperative complications, including nonroutine discharge, increased hospital charges, and the length of stay.

Higher rates of obesity, older age, and the higher incidence of other concurrent medical problems found in patients with diabetes may predispose patients to complications and prolonged hospitalization after surgery. Fang et al13 found that preoperative risk factors for infection included smoking, age greater than 60 years, diabetes, previous surgical infection, increased BMI, and alcohol abuse. Deyo et al39 found that age was a significant factor in morbidity and mortality in lumbar spine surgery. Katz et al40 also found that patients with diabetes had a high incidence of comorbidity after lumbar spine decompression. Further research is necessary to learn about the interaction and importance of these individual risk factors in predisposing patients to less-optimal outcomes and higher complication rates.

The greatest limitation of this study was the small number of diabetic patients in the IDH subgroup. While the number of patients with diabetes is a reasonable representation of patients with diabetes in the IDH age range, the population of patients with diabetes in the IDH population is small. Therefore, final conclusions on whether or not patients with diabetes improve with discectomy for IDH should be made with caution, and a future study with greater numbers of diabetic patients must be undertaken to come to a more-definitive conclusion. In addition, we do not have any information about the baseline or posttreatment status of the diabetes in these patients with regard to glycemic control. The type, chronicity, and degree of control of diabetes mellitus have an impact on neurologic and vascular sequelae of the disease. This in turn, would be expected to influence the diagnosis, treatment, outcomes, and potential complications of the treatment of spinal disorders. A prospective study that takes these factors into account would help to clarify the patients who are most likely to have the best outcome and fewest complications with the various surgical and nonsurgical treatments. Furthermore, a routine screen for diabetes with a 2-hour postprandial blood glucose for all patients might well have diagnosed more patients with diabetes than was seen in our study. This might have changed our baseline as well as our outcome and complication data.1-3

CONCLUSION

This is the first prospective study to compare surgical and nonsurgical outcomes between diabetic patients and nondiabetic patients. Diabetic patients who underwent surgery for IDH did not make significant improvements in pain and function at 4 years. Both diabetic and nondiabetic patients with SpS and DS benefited from surgery with regard to alleviating pain and improving function. However, nondiabetic patients with SpS or DS made greater functional gains with surgical intervention than did patients with diabetes. Diabetic DS patients did not have as much improvement in pain with surgery as the nondiabetic DS population. Nonoperative treatment for nondiabetic SpS patients also resulted in significant gains relative to diabetic SpS patients with regard to function but not pain.

Key Points.

-

□

SPORT patients with diabetes are older, have higher BMIs, and have more comorbidities than nondiabetic patients.

-

□

Diabetic patients with intervertebral disc herniation did not make significant gains in pain and function with surgical intervention relative to diabetic patients who underwent nonoperative treatment.

-

□

Diabetic patients with spinal stenosis or degenerative spondylolisthesis experienced greater improvements in pain and function with surgical intervention when compared with nonoperative treatment.

-

□

Postoperative complications, but not postoperative infections, were more prevalent in patients with diabetes than in nondiabetic patients with SpS.

-

□

There was an increase in postoperative and intraoperative blood replacement in diabetic patients with DS.

TABLE 4. Subgroup Results from Adjusted* As-Treated Outcome Analysis by Diabetes for the Randomized and Observational Cohorts Combined Patients with Lumbar Spinal Stenosis.

| Outcome | 1-Yr | 2-Yr | 3-Yr | 4-Yr | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDH (RCT & OBS) | Diabetes | Surgical | Nonoperative | Treatment Effect,† OR (95% CI) |

Surgical | Nonoperative | Treatment Effect,† OR (95% CI) |

Surgical | Nonoperative | Treatment Effect,† OR (95% CI) |

Surgical | Nonoperative | Treatment Effect,† OR (95% CI) |

| Primary outcomes | |||||||||||||

| SF-36 bodily pain (0–100), mean (SE) |

Not diabetic | 29.4 (1.4) | 14 (1.6) | 15.4 (11.6 to 19.3) | 28.6 (1.4) | 15.6 (1.7) | 13 (9,17.1) | 28.1 (1.4) | 15 (1.8) | 13.2 (8.9 to 17.4) | 27.2 (1.5) | 13.8 (1.9) | 13.4 (8.8 to 18.1) |

| Diabetic‡ | 34 (3.4) | 15.6 (3.6) | 18.4 (9.6 to 27.1) | 27.6 (3.4) | 5 (3.9) | 22.5 (13.3 to 31.8) | 31.3 (3.5) | 9.1 (4.3) | 22.2 (12.1 to 32.3) | 22.3 (3.8) | 10.3 (4.6) | 12 (1 to 23) | |

| P § | 0.21 | 0.68 | 0.54 | 0.77 | 0.013 | 0.06 | 0.40 | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.23 | 0.49 | 0.81 | |

| SF-36 physical function (0–100), mean (SE) |

Not diabetic | 26 (1.3) | 11.2 (1.5) | 14.7 (11.1 to 18.3) | 23 (1.3) | 14.2 (1.6) | 8.9 (5.1 to 12.7) | 21.9 (1.3) | 11.1 (1.7) | 10.7 (6.8 to 14.7) | 21.3 (1.5) | 11.1 (1.8) | 10.2 (5.8 to 14.5) |

| Diabetic | 23.1 (3.3) | 9.3 (3.5) | 13.8 (5.7 to 22) | 16.9 (3.3) | 1.7 (3.7) | 15.2 (6.6 to 23.8) | 14 (3.4) | 1.5 (4.1) | 12.5 (3.1 to 21.9) | 12.9 (3.6) | 11.3 (4.3) | 1.6 (_8.6 to 11.8) | |

| P | 0.42 | 0.60 | 0.84 | 0.077 | 0.002 | 0.18 | 0.032 | 0.029 | 0.73 | 0.03 | 0.96 | 0.12 | |

| Mental component summary (0–100), mean (SE) |

Not diabetic | 3.9 (0.6) | 2.4 (0.7) | 1.5 (−0.1 to 3.1) | 3.4 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.7) | 1.5 (−0.2 to 3.2) | 2.9 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.5 (−0.3 to 3.3) | 2.4 (0.7) | 1 (0.8) | 1.4 (−0.6 to 3.4) |

| Diabetic | 1.7 (1.4) | 2.1 (1.5) | −0.4 (−4.1 to 3.3) | 4.5 (1.4) | −2.1 (1.6) | 6.6 (2.6 to 10.5) | 0.3 (1.5) | −2.5 (1.8) | 2.8 (−1.5 to 7.1) | 0.4 (1.6) | −4.4 (1.9) | 4.8 (0.1 to 9.4) | |

| P | 0.14 | 0.83 | 0.36 | 0.45 | 0.026 | 0.019 | 0.10 | 0.043 | 0.58 | 0.24 | 0.01 | 0.19 | |

| Oswestry Disability Index (0–100), mean (SE) |

Not diabetic | −21 (1) | −9.1 (1.2) | −11.9 (−14.7 to −9) | −20.6 (1) | −10.1 (1.2) | −10.5 (−13.5 to −7.5) | −18.9 (1.1) | −9.8 (1.3) | −9.1 (−12.3 to −6) | −18.9 (1.2) | −10.2 (1.4) | −8.7 (−12.2 to −5.3) |

| Diabetic | −21.7 (2.6) | −6.3 (2.8) | −15.4 (−22 to −8.8) | −17.9 (2.6) | −2.5 (3) | −15.4 (−22.3 to −8.4 | −16.1 (2.7) | −1.2 (3.3) | −14.9 (−22.5 to −7.3) | −15.9 (2.9) | −2.6 (3.5) | −13.3 (−21.6 to −5) | |

| P | 0.80 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.018 | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.015 | 0.16 | 0.34 | 0.044 | 0.31 | |

| Very/somewhat satisfied with symptoms (%) |

Not diabetic | 68.9 | 28.7 | 40.2 (31.6 to 48.7) | 71.6 | 29.1 | 42.5 (33.5 to 51.5) | 65.3 | 35.5 | 29.8 (19.7 to 39.9) | 65.1 | 31.9 | 33.3 (22.4 to 44.1) |

| Diabetic | 69.8 | 19.5 | 50.3 (32.6 to 67.9) | 54.9 | 19.1 | 35.8 (15.8 to 55.9) | 71.7 | 34.3 | 37.4 (14.9 to 59.9) | 48.5 | 27.5 | 21.1 (−4.1 to 46.2) | |

| P | 0.90 | 0.26 | 0.34 | 0.036 | 0.29 | 0.77 | 0.42 | 0.90 | 0.54 | 0.11 | 0.71 | 0.50 | |

| Very/somewhat satisfied with care (%) |

Not diabetic | 86.2 | 67.2 | 19 (10.8 to 27.2) | 83.5 | 66.7 | 16.8 (7.9 to 25.7) | 84.1 | 59.5 | 24.6 (14.8 to 34.4) | 79.8 | 62.5 | 17.3 (6.3 to 28.3) |

| Diabetic | 85.9 | 76 | 9.9 (−6.6 to 26.4) | 79.9 | 62.3 | 17.6 (−3.6 to 38.8) | 84.1 | 71.1 | 13 (−8.2 to 34.2) | 77.8 | 73.8 | 4 (−19.8 to 27.9) | |

| P | 0.95 | 0.31 | 0.47 | 0.55 | 0.69 | 0.93 | 1 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.80 | 0.41 | 0.43 | |

| Self-rated progress major improvement (%) |

Not diabetic | 68 | 25.6 | 42.5 (34.2 to 50.7) | 66.5 | 27.1 | 39.4 (30.6 to 48.2) | 61.7 | 29.1 | 32.6 (23.1 to 42.2) | 54 | 23.3 | 30.7 (20.5 to 40.9) |

| Diabetic | 72.1 | 19.5 | 52.6 (35.5 to 69.7) | 47 | 26.1 | 20.9 (0 to 41.7) | 60.9 | 21.1 | 39.8 (19.1 to 60.6) | 44.1 | 12.7 | 31.3 (10.6 to 52.1) | |

| P | 0.59 | 0.42 | 0.34 | 0.031 | 0.92 | 0.24 | 0.93 | 0.43 | 0.55 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.68 | |

Adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, work status, income, smoking status, self-assessed health trend at baseline, treatment preference, baseline score (for SF-36, ODI), baseline stenosis bothersomeness, and center.

Treatment effect is the difference between the surgical and nonoperative mean change from baseline. Analysis is done by using a mixed model with a random subject intercept term. Treatment is a time-varying covariate where a patients’ experience before surgery is attributed to the nonoperative arm, and time is measured from enrollment; his(her postsurgery outcomes are attributed to the surgical arm, and time is measured from the time of surgery.

Patients who report being told by their doctors that they have diabetes and also report that they are currently receiving treatment for diabetes.

P values at each time-point are from multiple degree-of-freedom Wald tests.

CI indicates confidence interval; OBS, …; OR, odds ratio; RCT, …; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; SpS, spinal stenosis.

TABLE 5. Subgroup Results from Adjusted* As-Treated Outcome Analysis by Diabetes for the Randomized and Observational Cohorts Combined Patients with Lumbar Lumbar.

| Outcome | 1-Yr | 2-Yr | 3-Yr | 4-Yr | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDH (RCT & OBS) | Diabetes | Surgical | Nonoperative | Treatment Effect,† OR (95% CI) |

Surgical | Nonoperative | Treatment Effect,† OR (95% CI) |

Surgical | Nonoperative | Treatment Effect,† OR (95% CI) |

Surgical | Nonoperative | Treatment Effect,† OR (95% CI) |

| Primary outcomes | |||||||||||||

| SF-36 bodily pain (0–100), mean (SE) |

Not diabetic | 33 (1.3) | 14 (1.5) | 19 (15.4 to 22.7) | 33.3 (1.3) | 13.2 (1.6) | 20.1 (16.2 to 24.1) | 33.9 (1.4) | 15.3 (1.8) | 18.6 (14.5 to 22.8) | 32.2 (1.5) | 15.5 (1.9) | 16.7 (12.2 to 21.2) |

| Diabetic‡ | 29.9 (3.9) | 12.5 (4.2) | 17.3 (6.7 to 28) | 21.9 (3.6) | 11.6 (4.5) | 10.3 (−0.3 to 20.9) | 22.7 (3.7) | 13.5 (4.9) | 9.2 (−2.3 to 20.7) | 27.3 (4.2) | 16.7 (5.3) | 10.6 (−2.1 to 23.3) | |

| P § | 0.44 | 0.74 | 0.77 | 0.003 | 0.74 | 0.085 | 0.004 | 0.74 | 0.13 | 0.27 | 0.83 | 0.37 | |

| SF-36 physical function (0–100), mean (SE) |

Not diaetic | 28.5 (1.3) | 10.9 (1.4) | 17.6 (14.2 to 21.1) | 27.3 (1.3) | 9.8 (1.6) | 17.4 (13.7 to 21.2) | 26.3 (1.3) | 8.7 (1.7) | 17.6 (13.7 to 21.6) | 27.7 (1.4) | 7.8 (1.8) | 19.9 (15.6 to 24.2) |

| Diabetic | 27.8 (3.8) | 8.6 (4.1) | 19.2 (9.1 to 29.4) | 16.1 (3.5) | 5.5 (4.3) | 10.6 (0.5 to 20.7) | 14.8 (3.6) | 9.9 (4.8) | 4.9 (−6.3 to 16) | 18.9 (4) | 8.7 (5.2) | 10.2 (−2.1 to 22.5) | |

| P | 0.86 | 0.59 | 0.77 | 0.003 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.002 | 0.81 | 0.032 | 0.037 | 0.87 | 0.14 | |

| Mental component summary (0–100), mean (SE) |

Not diabetic | 2.8 (0.5) | 1.5 (0.6) | 1.3 (−0.2 to 2.9) | 2.9 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.7) | 1.6 (0 to 3.3) | 2.7 (0.6) | 0.5 (0.7) | 2.2 (0.4 to 4) | 2.7 (0.6) | 0.4 (0.8) | 2.4 (0.4 to 4.3) |

| Diabetic | 4.9 (1.6) | 1.5 (1.7) | 3.4 (−1.1 to 7.8) | 0.7 (1.5) | −1.8 (1.9) | 2.5 (−2 to 7) | 0.6 (1.5) | −2.1 (2.1) | 2.7 (−2.2 to 7.6) | 0.1 (1.8) | −2.9 (2.4) | 3 (−2.7 to 8.7) | |

| P | 0.20 | 0.96 | 0.39 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.72 | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.86 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.83 | |

| Oswestry Disability Index (0–100), mean (SE) |

Not diabetic | −24.8 (1) | −7.9 (1.1) | −16.9 (−19.5 to −14.2) | −24.7 (1) | −7.7 (1.2) | −17 (_19.9 to −14.1) | −22.6 (1) | −8.8 (1.3) | −13.8 (−16.9 to −10.8) | −23.5 (1.1) | −8 (1.4) | −15.6 (−18.9 to −12.3) |

| Diabetic | −27.5 (3) | −7.8 (3.2) | −19.7 (−27.6 to −11.9) | −18.5 (2.8) | −9.3 (3.4) | −9.2 (−17.2 to −1.3) | −16.9 (2.9) | −11.4 (3.6) | −5.5 (−13.9 to 3) | −20.3 (3.1) | −12.7 (4) | −7.6 (−17 to 1.9) | |

| P | 0.39 | 0.96 | 0.50 | 0.033 | 0.66 | 0.068 | 0.056 | 0.49 | 0.065 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.11 | |

| Very/somewhat satisfied with symptoms (%) |

Not diabetic | 71.9 | 26.8 | 45 (37.3 to 52.8) | 70.6 | 32.4 | 38.3 (29.6 to 47) | 66.9 | 37 | 30 (20.3 to 39.6) | 64.2 | 28.9 | 35.3 (25.3 to 45.4) |

| Diabetic | 81.4 | 30.8 | 50.6 (29.3 to 72) | 61.4 | 30.4 | 31 (7 to 55) | 62.4 | 28.9 | 33.5 (7.7 to 59.2) | 68.6 | 39.7 | 28.9 (−1 to 58.9) | |

| P | 0.28 | 0.67 | 0.59 | 0.29 | 0.86 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.51 | 0.81 | 0.67 | 0.44 | 0.71 | |

| Very/somewhat satisfied with care (%) |

Not diabetic | 89.8 | 67.6 | 22.2 (14.7 to 29.7) | 88.4 | 68.3 | 20.1 (11.7 to 28.4) | 88 | 65.4 | 22.6 (13.4 to 31.8) | 86.1 | 66.9 | 19.2 (9 to 29.4) |

| Diabetic | 90.3 | 75.2 | 15.1 (−4.2 to 34.4) | 93.3 | 57.8 | 35.5 (13.7 to 57.4) | 86.7 | 86.9 | −0.2 (−18 to 17.6) | 91.7 | 63.6 | 28.1 (1.8 to 54.5) | |

| P | 0.92 | 0.44 | 0.67 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.19 | 0.83 | 0.024 | 0.08 | 0.38 | 0.80 | 0.41 | |

| Self-rated progress major improvement (%) |

Not diabetic | 74.8 | 24.7 | 50.1 (42.6 to 57.6) | 74.7 | 23.6 | 51.1 (43.1 to 59.1) | 72.1 | 23.8 | 48.3 (39.8 to 56.8) | 66.9 | 19.1 | 47.8 (38.7 to 56.9) |

| Diabetic | 84.1 | 26.5 | 57.5 (37.2 to 77.9) | 63.2 | 19.5 | 43.8 (22.3 to 65.3) | 65.5 | 30.7 | 34.8 (9 to 60.5) | 76 | 32.5 | 43.5 (15.3 to 71.7) | |

| P | 0.23 | 0.86 | 0.50 | 0.18 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.44 | 0.55 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.75 | |

Adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, work status, income, smoking status, self-assessed health trend at baseline, treatment preference, baseline score (for SF-36, ODI), baseline stenosis bothersomeness, and center.

Treatment effect is the difference between the surgical and nonoperative mean change from baseline. Analysis is done by using a mixed model with a random subject intercept term. Treatment is a time-varying covariate where a patients’ experience before surgery is attributed to the nonoperative arm, and time is measured from enrollment; his/her postsurgery outcomes are attributed to the surgical arm, and time is measured from the time of surgery.

Patients who report being told by their doctors that they have diabetes and also report that they are currently receiving treatment for diabetes.

P values at each time-point are from multiple degree-of-freedom Wald tests.

CI indicates confidence interval; OBS, …; OR, odds ratio; RCT, …; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; SpS, spinal stenosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (U01-AR45444) and the Office of Research on Women’s Health, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

No funds were received in support of this work. No benefits in any form have been or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this manuscript.

Footnotes

The manuscript submitted does not contain information about medical device(s)/drug(s).

References

- 1.Bailes BK. Diabetes mellitus and its chronic complications. AORN J. 2002;76:266–76. 78–82. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)61065-x. quiz 83-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloomgarden ZT. Diabetes complications. Diab Care. 2004;27:1506–14. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duby JJ, Campbell RK, Setter SM, et al. Diabetic neuropathy: an intensive review. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61:160–73. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.2.160. quiz 75-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldman EL, Russell JW, Sullivan KA, et al. New insights into the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy. Curr Opin Neurol. 1999;12:553–63. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199910000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guthrie RA, Guthrie DW. Pathophysiology of diabetes mellitus. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2004;27:113–25. doi: 10.1097/00002727-200404000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheetz MJ, King GL. Molecular understanding of hyperglycemia’s adverse effects for diabetic complications. JAMA. 2002;288:2579–88. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.20.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Airaksinen O, Herno A, Turunen V, et al. Surgical outcome of 438 patients treated surgically for lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 1997;22:2278–82. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199710010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arinzon Z, Adunsky A, Fidelman Z, et al. Outcomes of decompression surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis in elderly diabetic patients. Eur Spine J. 2004;13:32–7. doi: 10.1007/s00586-003-0643-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bendo JA, Spivak J, Moskovich R, et al. Instrumented posterior arthrodesis of the lumbar spine in patients with diabetes mellitus. Am J Orthop. 2000;29:617–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cinotti G, Postacchini F, Weinstein JN. Lumbar spinal stenosis and diabetes. Outcome of surgical decompression. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76:215–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simpson JM, Silveri CP, Balderston RA, et al. The results of operations on the lumbar spine in patients who have diabetes mellitus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1823–9. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199312000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Browne JA, Cook C, Pietrobon R, et al. Diabetes and early postoperative outcomes following lumbar fusion. Spine. 2007;32:2214–9. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31814b1bc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang A, Hu SS, Endres N, et al. Risk factors for infection after spinal surgery. Spine. 2005;30:1460–5. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000166532.58227.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glassman SD, Alegre G, Carreon L, et al. Perioperative complications of lumbar instrumentation and fusion in patients with diabetes mellitus. Spine J. 2003;3:496–501. doi: 10.1016/s1529-9430(03)00426-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wimmer C, Gluch H, Franzreb M, et al. Predisposing factors for infection in spine surgery: a survey of 850 spinal procedures. J Spinal Disord. 1998;11:124–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Diabetes Association [Accessed May 27, 2005];National diabetes fact sheet. http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-statistics.jsp.

- 17.Gregg EW, Cadwell BL, Cheng YJ, et al. Trends in the prevalence and ratio of diagnosed to undiagnosed diabetes according to obesity levels in the U.S. Diab Care. 2004;27:2806–12. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Center for Health Statistics [Accessed May 27, 2005];Diabetes. http//www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/diabetes.htm.

- 19.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2257–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) observational cohort. JAMA. 2006;296:2451–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.20.2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical therapy for lumbar spinal stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:794–810. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar disc herniation: four-year results for the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) Spine. 2008;33:2789–800. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818ed8f4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Birkmeyer NJ, Weinstein JN, Tosteson AN, et al. Design of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) Spine. 2002;27:1361–72. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200206150-00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Rogers W, et al. The validity and relative precision of MOS short- and long-form health status scales and Dartmouth COOP charts. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care. 1992;30:MS253–65. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199205001-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, et al. The Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy. 1980;66:271–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, et al. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT): a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2441–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.20.2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lurie, 2008

- 29.Park, In press, 2009.

- 30.Pearson, In press, 2009.

- 31.Tosteson, 2007.

- 32.Resnick HE, Vinik AI, Schwartz AV, et al. Independent effects of peripheral nerve dysfunction on lower-extremity physical function in old age: the Women’s Health and Aging Study. Diab Care. 2000;23:1642–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.11.1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kreines K, Johnson E, Albrink M, et al. The course of peripheral vascular disease in non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Diab Care. 1985;8:235–43. doi: 10.2337/diacare.8.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blau J, Logue V. Intermittent claudication of the cauda equina. Lancet. 1961;2:1081–6. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dyck PJ, Karnes JL, O’Brien P, et al. The spatial distribution of fiber loss in diabetic polyneuropathy suggests ischemia. Ann Neurol. 1986;19:440–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.410190504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cimbiz A, Cakir O. Evaluation of balance and physical fitness in diabetic neuropathic patients. J Diab Complications. 2005;19:160–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gutierrez EM, Helber MD, Dealva D, et al. Mild diabetic neuropathy affects ankle motor function. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2001;16:522–8. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(01)00034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ozdirenc M, Biberoglu S, Ozcan A. Evaluation of physical fitness in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diab Res Clin Pract. 2003;60:171–6. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(03)00064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Loeser JD, et al. Morbidity and mortality in association with operations on the lumbar spine. The influence of age, diagnosis, and procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:536–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katz JN, Lipson SJ, Larson MG, et al. The outcome of decompressive laminectomy for degenerative lumbar stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:809–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical compared with nonoperative treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. four-year results in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) randomized and observational cohorts. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1295–304. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Engelgau MM, Geiss LS, Saaddine JB, et al. The evolving diabetes burden in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:945–50. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-11-200406010-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]