Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is the standard of care for axillary staging in clinically node-negative breast cancer patients. It is not known whether SLNB rates differ by surgeon expertise. If surgeons with less breast cancer expertise are less likely to offer SLNB to clinically node-negative patients, this practice pattern could lead to unnecessary axillary lymph node dissections (ALND) and lymphedema.

OBJECTIVE

To explore potential measures of surgical expertise (including a novel objective specialization measure – percentage of a surgeon’s operations devoted to breast cancer determined from claims) on the use of SLNB for invasive breast cancer.

DESIGN

Population-based prospective cohort study. Patient, tumor, treatment and surgeon characteristics were examined.

SETTING

California, Florida, Illinois

PARTICIPANTS

Elderly (65+ years) women identified from Medicare claims as having had incident invasive breast cancer surgery in 2003.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Type of axillary surgery performed.

RESULTS

Of the 1,703 women treated by 863 different surgeons, 56% underwent an initial SLNB, 37% initial ALND and 6% no axillary surgery. The median annual surgeon Medicare volume of breast cancer cases was 6 (range: 1.5–57); the median surgeon percentage of breast cancer cases was 4.6% (range: 0.7%–100%). After multivariable adjustment of patient and surgeon factors, women operated on by surgeons with higher volumes and percentages of breast cancer cases had a higher likelihood of undergoing SLNB. Specifically, women were most likely to undergo SLNB if operated on by high volume surgeons (regardless of percentage) or by lower volume surgeons with a high percentage of cases devoted to breast cancer. In addition, membership in the American Society of Breast Surgeons (OR 1.98, CI 1.51–2.60) and Society of Surgical Oncology (OR 1.59, CI 1.09–2.30) were independent predictors of women undergoing an initial SLNB.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Patients treated by surgeons with more experience and focus in breast cancer were significantly more likely to undergo SLNB, highlighting the importance of receiving initial treatment by specialized providers. Factors relating to specialization in a particular area, including our novel surgeon percentage measure, require further investigation as potential indicators of quality of care.

INTRODUCTION

Over the last two decades, sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) has been the single most important advance in the primary surgical treatment of clinically node-negative breast cancer. Compared to axillary lymph node dissection (ALND), which involves the removal of most axillary lymph nodes, SLNB involves the removal of only a few lymph nodes (average 2–3 nodes).1–5 Several large, randomized controlled trials demonstrate that SLNB is associated with similar disease-free survival when compared to ALND1,4–9 as well as a reduced likelihood of developing lymphedema and other arm/shoulder morbidity.1,4–6,10–17 For these reasons, SLNB is now the standard of care for axillary staging in clinically node-negative patients18–20 and is considered a surgical quality measure by certain organizations.21–23

Many women with breast cancer in the US are cared for by surgeons with low volumes of breast cancer cases.17,24–26 However, it is not known whether patients of low volume surgeons are as likely to undergo SLNB. If surgeons with less breast cancer expertise are less likely to offer SLNB to clinically node-negative patients, this practice pattern could lead to unnecessary ALNDs and cases of lymphedema.

In this report, we evaluate the relationship between surgeon characteristics and axillary surgery for invasive breast cancer by exploring several potential measures of surgeon expertise. One measure, surgeon volume of breast cancer cases, has been used as a measure of technical proficiency with regard to margin status and re-excision rates after breast-conserving surgery, use of axillary surgery, and adequacy of ALND.27–30 For this study, we also developed a novel objective measure of surgical specialization, the percentage of a surgeon’s operative cases that is devoted to breast cancer, as determined from claims data. Prior studies have evaluated the relationship of self-reported percentages of a surgeon’s practice devoted to breast surgery to the type of breast surgery performed, adequacy of ALND, and patient satisfaction.29–32 Other measures of expertise investigated included the number of years in practice and membership in surgical oncology and breast-specific societies. We explored these five measures of surgical expertise and receipt of initial axillary surgery in a population-based cohort of older breast cancer survivors.

METHODS

Data Sources

The study sample consists of a population-based cohort of elderly breast cancer survivors who participated in a National Cancer Institute-sponsored survey study examining breast cancer care outcomes. Women between the ages of 65 and 89 were identified from Medicare claims as having had an incident breast cancer surgery in 2003, using our validated claims-based algorithm.33 Details regarding study recruitment and assessments have been previously described.17,34 Briefly, potential participants were contacted by mail in September 2005 and four subsequent annual structured telephone interviews were conducted. For this study, the cohort consists of 1,703 women with invasive breast cancer who completed all four waves of the survey, had complete information regarding pathologic nodal status, and had a surgeon identifiable by Medicare claims.

Tumor characteristics and stage was provided by state cancer registries.35 Medicare claims information was collected from inpatient, outpatient and carrier Standard Analytical Files. Surgeon characteristics were obtained from the American Medical Association’s (AMA) Physicians Professional Database (Table 1).36,37 Society membership was determined from online directories of the Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO)38 and American Society of Breast Surgeons (ASBrS).39 Surgeons were not contacted directly for this study.

Table 1.

Variable definitions and data source

| Variable | Data source |

|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | |

| Age | Medicare claims |

| State of residence | Medicare claims |

| California, Illinois or New York | |

| Race | Patient survey |

| White, Black or African American, Asian, native | |

| Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American | |

| Indian/Alaska Native, or other | |

| Body mass index (BMI) at time of surgerya | Patient survey |

| Comorbidityb | Medicare claims |

|

| |

| Pathologic tumor characteristics | |

| Tumor size | State tumor registryc |

| Lymph node status | State tumor registry |

| Number of lymph nodes removed | State tumor registry |

|

| |

| Treatment variables | |

| Type of breast surgery | Medicare claims |

| Breast-conserving surgery | |

| Mastectomy | |

| Type of axillary surgery | Medicare claims |

| None | |

| Sentinel node biopsy (SLNB) | |

| Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) | |

| Radiation therapy | Patient survey |

| Chemotherapy | Patient survey |

| Hormonal therapy within one year of surgery | Patient survey |

|

| |

| Surgeon factors | |

| Surgeon characteristics | American Medical Association |

| Gender (self-report) | Physicians Professional Databased |

| Medical school location (LCME primary source) | |

| Year of medical school graduation (ACGME primary source) | |

| Surgical specialty (self-report) | |

| General surgery, surgical oncology or other | |

| Academic affiliation (self-report) | |

| American Society of Breast Surgeons (ASBrS) membership | Society directory |

| Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO) membership | Society directory |

| Surgeon volume of Medicare breast cancer cases | Medicare claims |

| Surgeon percentage of Medicare operations performed for breast cancer | Medicare claims |

Abbreviations: ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; LCME, Liaison Committee on Medical Education

Body mass index was calculated by self-reported height and weight at the time of surgery.

Comorbidity was determined from inpatient, outpatient and carrier Medicare claims for the year preceding the incident breast cancer diagnosis, based on the NCI Combined Comorbidity Index algorithm by Klabunde which is specific for breast cancer patients.61

The three state tumor registries (Florida, Illinois, California) have achieved Gold-level certification by the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries.35

The American Medical Association’s Physician Masterfile was established in 1906 and currently includes information from more than 1.4 million physicians, residents and medical students in the US. It is considered the most accurate source of information on physician characteristics. Information regarding medical education, residency training or other professional certification data is verified from the primary source while other information (surgical specialty and academic affiliation) is self-reported. Physicians are contacted by the AMA periodically to update their Masterfile.

Variable Definitions

Table 1 summarizes the various patient, tumor, treatment and surgeon characteristics examined and the source of information. Medicare claims data were used to determine the type of axillary surgery performed.40–42 Patients were classified into one of three groups: 1) no axillary surgery; 2) initial SLNB, which includes patients who underwent only SLNB and those who went on to completion ALND either during the same operation or subsequent surgery; 3) initial ALND. Procedure codes in 2003 for SLNB included: injection of the radioactive tracer or dye (Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] A9520, 38790, 38792) and removal of sentinel lymph nodes (CPT 38500, 38525). ALND procedural codes included codes that referred to only axillary surgery (CPT 38740, 38745) and those that included combined breast and axillary procedures (CPT 19162, 19200, 19220, 19240).

Surgeon Characteristics

Provider codes from Medicare claims of the surgeons operating on cohort patients were linked to the 2004 AMA’s Physicians Professional Database to obtain surgeon characteristics. Surgeons were considered to have an academic affiliation if they performed the majority of their breast operations in an Association of American Medical Colleges Council of Teaching Hospitals and Health systems hospital,43 were employed by a medical school, or primarily practiced medical research or education. Medicare claims were used to determine annual Medicare surgeon volume of breast cancer cases, as previously described,17,44 based on claims for all breast cancer cases treated in each state, not solely for cohort subjects.

The novel objective measure (surgeon percentage of practice devoted to breast cancer cases) was created. For each surgeon, the annual number of patients who underwent an initial breast cancer surgery was divided by the number of patients who underwent a general surgery operation performed that same year. General surgery operations were defined by CPT codes 10021 –69990 and all patient refined diagnosis related groups (APR-DRGs) surgical “P” codes.41,45 This specialization measure was based on Medicare claims for all surgeries performed in each state, not solely for cohort subjects.

Statistical Analysis

The conceptual framework was to model 1) the decision to perform axillary surgery; and if done, 2) which type of axillary surgery (initial SLNB or ALND) was performed. We hypothesized that surgeon characteristics would affect the type of axillary surgery performed in a fashion incremental to clinically important, preoperative factors. Variables included in these analyses were determined a priori: five surgeon characteristics (surgeon percentage, surgeon volume, membership in ASBrS or SSO, and years since medical school graduation), three patient characteristics (age, BMI, comorbidities), and geographic location. Tumor characteristics (clinical stage, hormone receptor and HER2-neu status) could not be included as this information was not consistently recorded in the state tumor registries.

The two axillary surgery outcomes were analyzed by separate multiple logistic regression modeling. The first model included the entire cohort and examined the independent effects of various surgeon and patient characteristics on the likelihood of undergoing axillary surgery (initial SLNB or ALND vs. no axillary surgery). In the subset of women who underwent axillary surgery, the second model examined the relationship between these same characteristics and the likelihood of undergoing initial SLNB vs. ALND.

Data analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software (Version 9.3, SAS Institute; Cary, NC). This study was approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Privacy Board, our institution’s and each tumor registry’s Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

The mean age of the 1,703 women at the time of surgery was 72.9 (SD 5.6) years; 91% were white. At the time of surgery, 36% of women were underweight or normal weight (BMI <25), 31% overweight (BMI 25 – <30), 22% obese (BMI≥30) and 11% unknown. The majority of women (62%) were healthy with an NCI combined comorbidity score of 0; 32% had a score > 0, and 6% were unknown. Most women had early stage disease: 70% had T1 tumors (tumor size < 2 cm); 19% had T2 tumors (2–5 cm) and 3% had tumors > 5 cm in size; 9% had no reported tumor size. Twenty-two percent of women had lymph node involvement. Almost two-thirds (62%) underwent breast-conserving surgery; 38% underwent mastectomy. No axillary surgery was performed in 6%, while 56% underwent an initial SLNB and 37% initial ALND. The mean number of lymph nodes removed was 7.1 [SD 6.7; range: 0 – 44; interquartile range: 9 (2 – 11)]. Women undergoing ALND had an average of 9.2 (SD 6.8) nodes removed, compared to 3.0 (SD 3.2) for those undergoing SLNB (p<0.001). Two-thirds of the cohort received radiation therapy, 23% chemotherapy, and 68% hormonal therapy.

Surgeon characteristics

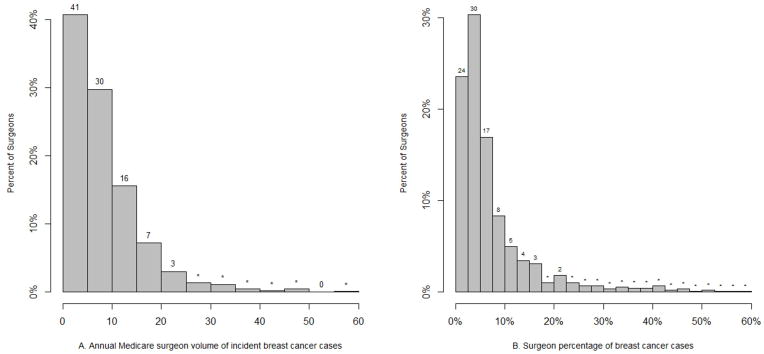

Table 2 details the characteristics of the 863 surgeons who operated on these 1,703 women. The majority were male, graduated from a U.S. medical school, and were general surgeons. Small minorities were surgical oncologists, had an academic affiliation, or were ASBrS or SSO members. Figure 1 shows the distribution of surgeon volume and surgeon percentage. The median annual Medicare volume was 6 cases (range: 1.5 to 57; interquartile range: 7.5 (3.0 – 10.5). Overall, 41% of surgeons performed fewer than 6 incident Medicare breast cancer cases annually, which equates to fewer than 15 cases in women of all ages.

Table 2.

Characteristics of 863 surgeons, by surgeon percentage measure

| Surgeon characteristics | Total surgeon cohort (n = 863) | Surgeon percent ≥ 10% (n = 181) | Surgeon percent < 10% (n = 682) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Gendera | <0.0001 | |||

| Male | 739 (86%) | 100 (56%) | 639 (94%) | |

| Female | 120 (14%) | 80 (44%) | 40 (6%) | |

|

| ||||

| Medical school traininga | 0.010 | |||

| U.S. | 702 (81%) | 159 (88%) | 543 (80%) | |

| Non-U.S. | 157 (18%) | 21 (11%) | 136 (20%) | |

|

| ||||

| Years since medical school graduationa | 0.38 | |||

| More than 30 (1973 and earlier) | 277 (32%) | 61 (34%) | 201 (30%) | |

| 20 – 30 (1974 – 1984) | 320 (37%) | 68 (38%) | 252 (37%) | |

| Less than 20 (since 1985) | 262 (30%) | 51 (28%) | 226 (33%) | |

|

| ||||

| Surgeon specialty | <0.0001 | |||

| General surgery | 781 (90%) | 157 (87%) | 24 (92%) | |

| Surgical oncology | 21 (2%) | 14 (8%) | 7 (1%) | |

| Other | 61 (7%) | 10 (6%) | 51 (7%) | |

|

| ||||

| Academic surgeon | 88 (10%) | 45 (25%) | 43 (6%) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| ASBrS memberb | 165 (19%) | 69 (39%) | 96 (14%) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| SSO memberb | 84 (10%) | 50 (28%) | 34 (5%) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Mean annual Medicare surgeon volume of breast cancer cases (SD) | 8.5 (7.3) | 19.7 (12.3) | 7.5 (5.7) | <0.0001 |

| 0 – <6 | 351 (41%) | 27 (15%) | 324 (48%) | |

| 6 – <12 | 308 (36%) | 55 (30%) | 253 (37%) | |

| 12 or more | 204 (24%) | 99 (55%) | 105 (15%) | |

Abbreviations: ASBrS, American Society of Breast Surgeons; SD, standard deviation; SSO, Society of Surgical Oncology; U.S., United States.

Excludes 4 surgeons with missing information

Excludes 8 surgeons with missing information

Figure 1.

Distribution of surgeon volume (Figure 1A) and surgeon percentage (Figure 1B) among the 863 surgeons. Surgeon volume or surgeon percentage is displayed on the x-axis; the percentage of surgeons in each category is displayed on the y-axis. In Figure 1B, two surgeons are excluded who had a surgeon percentage > 60%. In each Figure, the percent of surgeons in each bar is represented by the number above the bar. Bars marked with an “*” represent percentage values less than 1%. In Figure 1B, the sum of all bar percents (24%, 30%, 17% and 8%) between the 0 and 10% x-axis hatch mark shows that 79% of surgeons devote less than 10% of their operative cases to breast cancer. The remaining 21% of surgeons (sum of all bar percents after the surgeon percentage 10% x-axis hatch mark) devote 10% or more of their operative cases to breast cancer.

Among all Medicare operations performed by the 863 surgeons during one year, the median percentage of breast cancer cases was 4.6% (range: 0.7% to 100%; interquartile range: 6.2% [2.6% to 8.8%]). Twenty-one percent of surgeons (n=181) devoted 10% or more of their operations to breast cancer (Table 2, Figure 1b) and performed more than twice as many breast cancer operations annually as surgeons devoting less than 10% of their operations to breast cancer (19.7 vs. 7.5; Table 2). These surgeons were more likely to be female, a surgical oncologist, members of the ASBrS and SSO, and have an academic affiliation. Only 8% and 4% of surgeons devoted more than 20% and 30% of their operations to breast cancer, respectively.

Independent predictors of undergoing axillary surgery

Of the entire cohort, 94% underwent either SLNB or ALND and 6% (n=108) underwent no axillary surgery. In the multiple logistic regression model, when adjusting for surgeon and patient characteristics, the only independent predictor of undergoing any axillary surgery (SLNB or ALND) was patient age. Compared to women aged 65–69 years, women 80 years and older were significantly less likely to undergo any axillary surgery (OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.12 – 0.36). Patient BMI, comorbidity and all five surgeon characteristics were not predictors of a woman’s likelihood of undergoing axillary surgery.

Independent predictors of undergoing initial SLNB

Among the 1,585 women who underwent axillary surgery, 60% underwent initial SLNB and 40% ALND. Women operated on by surgeons who were members of ASBrS or SSO were more likely to undergo SLNB (Table 3). Since there was no interaction between ASBrS and SSO membership (p = 0.92), the effects of society membership are additive. Women undergoing an operation by surgeons who were members of both ASBrS and SSO had a 3.14 odds ratio of undergoing SLNB (95% CI 2.02 – 4.87).

Table 3.

Logistic regression model predicting the performance of initial SLNB vs. ALND in 1,585 women who underwent axillary surgerya

| Variables | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

|

Surgeon characteristics

| |||

| Percent of Medicare operations performed annually for breast cancer

|

|

|

|

| Annual Medicare surgeon volume of breast cancer cases

| |||

| Interaction between surgeon volume and surgeon percent | |||

|

| |||

| ASBrS member | <0.0001 | ||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.98 | 1.51 – 2.60 | |

|

| |||

| SSO member | 0.02 | ||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.59 | 1.09 – 2.30 | |

|

| |||

| Years since medical school graduation | 0.22 | ||

| More than 30 | 1.00 | ||

| 20 – 30 | 1.08 | 0.84 – 1.39 | |

| Less than 20 | 1.27 | 0.96 – 1.68 | |

|

| |||

| Patient characteristics | |||

|

| |||

| Age at time of surgery | 0.0009 | ||

| 65 – 69 | 1.00 | ||

| 70 – 74 | 0.70 | 0.54 – 0.92 | |

| 75 – 79 | 0.87 | 0.65 – 1.17 | |

| 80+ | 0.50 | 0.35 – 0.72 | |

Adjusted for comorbidity, BMI, geographic location

Abbreviations: ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; ASBrS, American Society of Breast Surgeons; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy; SSO, Society of Surgical Oncology.

Excludes 10 patients with missing information

The presence of an interaction renders the p-values for each individual variable not interpretable. The reported p-value is for a three-way degree of freedom test.

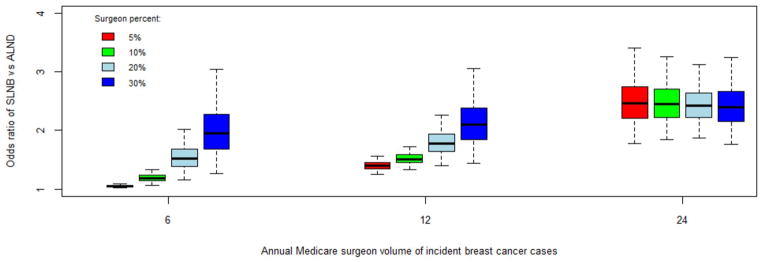

Women operated on by surgeons who had higher breast cancer volumes and higher percentages of breast cancer cases were also more likely to undergo SLNB. These two effects, however, were not additive as there is an interaction between these two variables (p<0.0001). Figure 2 displays the relationship between surgeon volume, surgeon percentage and the odds ratio of undergoing SLNB vs. ALND. All odds ratios are in reference to the baseline odds for a surgeon who performs six breast cancer cases annually and devotes 3% of all surgeries to breast cancer cases (baseline surgeon). For a low volume surgeon (annual volume of 6 Medicare cases), the likelihood of a patient undergoing SLNB increases significantly with increasing surgeon percentage of breast cancer cases. Compared to the baseline surgeon, the odds ratio of a patient undergoing an initial SLNB ranges from 1.05 (95% CI 1.02– 1.09) if her surgeon’s percentage of breast cancer operations is 5% to 1.96 (95% CI 1.03 – 3.05) if surgeon percentage is 30%. As surgeon volume increases, the incremental effect of surgeon percentage on the odds ratio of receiving an SLNB diminishes. If a surgeon performs 12 Medicare breast cancer cases annually, the odds ratio of a patient receiving an SLNB ranges from 1.40 (95% CI 1.25 – 1.56) to 2.09 (95% CI 1.44 – 3.05) as her surgeon’s percentage rises from 5% to 30%. At a high surgeon volume of 24 annual Medicare cases (equates to about 60 annual cases of all ages), the effect of surgeon proportion is negligible.

Figure 2.

Graph of annual Medicare surgeon volume (x-axis) and the odds ratio of undergoing sentinel node biopsy (SLNB) vs. axillary lymph node dissection (ALND; y-axis) relative to the baseline odds of undergoing SLNB for a surgeon who performs six annual incident Medicare breast cancer and devotes 3% of all surgeries to breast cancer cases. Various surgeon percentage values are represented by the colored boxes (red, 5%; green, 10%; light blue, 20%; dark blue, 30%). For each box, the black line represents the odds ratio estimate; the box represents the limits of the 50% confidence interval; the whiskers (dotted lines) represent the 95% confidence intervals.

Similarly, the incremental effect of surgeon volume on surgeon percent is greatest at the lower surgeon percentages (5% and 10%; red and green bars). As surgeon percentage increases, the effect of surgeon volume becomes minimal. When surgeon percentage is 30% (dark blue bars; only 4% of the surgeons in this cohort), the incremental effect of surgeon volume is negligible. With increasingly higher surgeon volume and surgeon percentage values, the confidence intervals widen significantly; caution must be used in interpreting the model results at the high end of surgeon volume and surgeon percentage values.

DISCUSSION

In this population-based cohort of over 1,700 older invasive breast cancer survivors treated by 863 predominantly community-based general surgeons, 56% underwent an initial SLNB procedure while 37% underwent an initial ALND and 6% underwent no axillary surgery. The surgeon characteristics evaluated in this study were measurable factors which we believed would reflect experience with breast cancer (case volume, years since medical school graduation) or degree of focus or specialization in breast cancer (percentage of total surgeries performed for breast cancer, ASBrS and SSO membership). None of these five surgeon factors were predictive of a woman’s likelihood of undergoing axillary surgery. However, if a woman underwent axillary surgery, surgeon percentage of breast cancer surgeries, case volume, and membership in either ASBrS or SSO were associated with the likelihood of a woman undergoing an SLNB, controlling for patient age, BMI, and comorbidity.

Specialization has been found to be beneficial in other areas of health care delivery (e.g., critical care intensivists46,47). Our study results would support some degree of specialization as benefitting breast cancer patients. Surgeons who dedicate a larger percentage of their practice to breast cancer or are members of breast and surgical oncology societies may have a greater motivation to become facile with treatment advances, such as SLNB. However, it would be difficult from a health policy perspective to base provider recommendations on professional society membership as it is a surgeon’s choice to join professional societies and membership requirements vary by society. Therefore, we favor the objective measure of percentage of a surgeon’s practice that is devoted to breast cancer (specialization construct), in addition to surgeon volume of breast cancer cases (experience construct), as a potential surgical quality marker.

Both higher surgeon volume and higher surgeon percentage of breast cancer cases were associated with a higher likelihood of a patient undergoing an initial SLNB. However, this relationship between surgeon volume and surgeon percentage is somewhat complex (Figure 2). As one variable increases (e.g. surgeon volume), the effect of the other variable (e.g. surgeon percentage) decreases. The incremental effect of higher surgeon percentage on a high volume surgeon’s likelihood of performing an SLNB is marginal but the incremental effect of higher surgeon percentage on a low volume surgeon’s likelihood of performing SLNB is substantial. This finding could partially explain why some low volume surgeons have good outcomes, if they are high percentage surgeons. Similarly, the incremental effect of surgeon volume on a high percentage surgeon’s likelihood of performing an SLNB is minor but the incremental effect of surgeon volume on a low percentage surgeon’s likelihood of performing SLNB is significant. We believe that this novel surgeon percentage measure further refines the surgeon volume measure and vice versa and warrants further investigation as a potential quality marker for surgical outcomes.

This study has several limitations. First, several tumor characteristics are typically known preoperatively and affect a surgeon’s decision to recommend axillary surgery. Information regarding the clinical tumor stage prior to surgery, hormone receptor and HER2-neu status were not routinely recorded in the 2003 state tumor registries; therefore, we could not conclusively determine which patients were appropriate candidates for SLNB. However, these factors are unlikely to vary systematically by surgeon characteristics. Second, misclassification of the outcome is possible since this axillary surgery variable was claims-based and defined by billing codes available in 2003. However, Medicare claims are generally accurate for breast cancer surgical billing codes.48,49

Lastly, as this study involves Medicare patients treated in 2003, a period when SLNB was considered an option to ALND for women with early stage breast cancer50,51 but was already widely adopted into clinical practice,52–54 our findings may not be generalizable to younger and more contemporary populations. Surprisingly, only 6% of women in this elderly cohort did not undergo any axillary surgery and if axillary surgery was performed, older women were more likely to receive ALND rather than SLNB. Studies in more current cohorts of elderly women should be performed as these findings are in contrast to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines which consider both SLNB and ALND optional in elderly patients.19,55,56 However, the fact that all patients were Medicare beneficiaries is a strength as we could identify surgeons based on claims information, calculate surgeon volume and percentage of breast cancer cases, and perform our analyses of various surgeon characteristics by linkage with other sources. An observational study of this magnitude affords us an opportunity to evaluate practice patterns in the community, where the majority of breast cancer treatment occurs.

Several previously reported measures of surgeon specialization in breast cancer have been based on subjective measures: local reputation, opinion, and surgeon self-reported proportion of their total practice devoted to breast cancer-related procedures.29–32,57,58 We believe that our novel objective measure, computed from health care claims, is likely to be a more reliable and sensitive surgeon-specific measure than these subjective measures and warrants further evaluation as a potential indicator of other aspects of breast cancer quality of care. Finally, this surgeon percentage/specialization measure may help refine studies that include surgeon volume in evaluating outcomes.

In summary, among this population-based, large cohort of older invasive breast cancer survivors, women operated on by surgeons who perform more breast cancer cases, focus their practice more on breast cancer, or are members of breast and surgical oncology societies were more likely to undergo an initial SLNB. Since women who undergo SLNB are at lower risk of developing lymphedema than those who undergo ALND, the importance of receiving initial treatment at centers that have experienced SLNB teams19 and surgeons who specialize in breast cancer must be emphasized to decrease lymphedema rates and its associated complications which significantly impact the quality of life and medical costs of survivors.13,16,59,60 Future studies addressing provider specialization are needed to determine whether this novel objective surgeon percentage measure is an indicator of improved outcomes and quality of cancer and non-cancer care.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This research was supported by a career development award and supplement to Dr. Yen from the National Cancer Institute (K07CA125586, K07CA125586-03S1) and two research grants from the National Cancer Institute to Dr. Nattinger (R01CA81379, R01CA127648).

Footnotes

Presented in part as an oral presentation at The Sixth Annual Academic Surgical Congress, Huntington Beach, CA, February 2011.

Author Contributions: Dr. Yen had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of data analysis.

The content does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Additional Contributions: We acknowledge the efforts of Changbin Guo, PhD, Mikesh Shivakoti, MS, and Jianing Li, MS for conducting data analyses and Thomas Chelius, MS for assisting with the acquisition and collection of data.

Role of Sponsor: The NIH had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None of the authors have been compensated specifically for work related to this manuscript other than having received research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to cover the costs of conducting the study. None of the authors have any financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Gill G. Sentinel-lymph-node-based management or routine axillary clearance? One-year outcomes of sentinel node biopsy versus axillary clearance (SNAC): a randomized controlled surgical trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(2):266–275. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0229-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langer I, Guller U, Berclaz G, et al. Morbidity of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLN) alone versus SLN and completion axillary lymph node dissection after breast cancer surgery: a prospective Swiss multicenter study on 659 patients. Ann Surg. 2007;245(3):452–461. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000245472.47748.ec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lucci A, McCall LM, Beitsch PD, et al. Surgical complications associated with sentinel lymph node dissection (SLND) plus axillary lymph node dissection compared with SLND alone in the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Trial Z0011. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(24):3657–3663. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Viale G, et al. A randomized comparison of sentinel-node biopsy with routine axillary dissection in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(6):546–553. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mansel RE, Fallowfield L, Kissin M, et al. Randomized multicenter trial of sentinel node biopsy versus standard axillary treatment in operable breast cancer: the ALMANAC Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(9):599–609. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zavagno G, De Salvo GL, Scalco G, et al. A Randomized clinical trial on sentinel lymph node biopsy versus axillary lymph node dissection in breast cancer: results of the Sentinella/GIVOM trial. Ann Surg. 2008;247(2):207–213. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31812e6a73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, et al. Technical outcomes of sentinel-lymph-node resection and conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in patients with clinically node-negative breast cancer: results from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase III trial. The lancet oncology. 2007;8(10):881–888. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70278-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node resection compared with conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in clinically node-negative patients with breast cancer: overall survival findings from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase 3 trial. The lancet oncology. 2010;11(10):927–933. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70207-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veronesi U, Viale G, Paganelli G, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer: ten-year results of a randomized controlled study. Ann Surg. 2010;251(4):595–600. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181c0e92a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erickson VS, Pearson ML, Ganz PA, Adams J, Kahn KL. Arm edema in breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(2):96–111. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.2.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrek JA, Pressman PI, Smith RA. Lymphedema: current issues in research and management. CA Cancer J Clin. 2000;50(5):292–307. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.50.5.292. quiz 308–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kissin MW, Querci della Rovere G, Easton D, Westbury G. Risk of lymphoedema following the treatment of breast cancer. Br J Surg. 1986;73(7):580–584. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800730723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engel J, Kerr J, Schlesinger-Raab A, Sauer H, Holzel D. Axilla surgery severely affects quality of life: results of a 5-year prospective study in breast cancer patients. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2003;79(1):47–57. doi: 10.1023/a:1023330206021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiel KD, Rademacker AW. Early-stage breast cancer: arm edema after wide excision and breast irradiation. Radiology. 1996;198(1):279–283. doi: 10.1148/radiology.198.1.8539394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meeske KA, Sullivan-Halley J, Smith AW, et al. Risk factors for arm lymphedema following breast cancer diagnosis in Black women and White women. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2009;113(2):383–391. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9940-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paskett ED, Naughton MJ, McCoy TP, Case LD, Abbott JM. The epidemiology of arm and hand swelling in premenopausal breast cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(4):775–782. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yen TW, Fan X, Sparapani R, Laud PW, Walker AP, Nattinger AB. A contemporary, population-based study of lymphedema risk factors in older women with breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(4):979–988. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0347-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyman GH, Giuliano AE, Somerfield MR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline recommendations for sentinel lymph node biopsy in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(30):7703–7720. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. [Accessed June 26, 2013.];NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Breast Cancer. 3.2013 http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#breast. [Google Scholar]

- 20.The American Society of Breast Surgeons. [Accessed June 26, 2013.];Official Statements. Guidelines for performing sentinel lymph node dissection in breast cancer. https://www.breastsurgeons.org/statements/guidelines.php.

- 21.American College of Surgeons. Cancer Programs. National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers (NAPBC) [Accessed June 26, 2013.];NAPBC Program Standards/Components. Components. http://napbc-breast.org/standards/standards.html.

- 22.National Consortium of Breast Centers (NCDB). National Quality Measures for Breast Centers (NQMBC) NQMBC-Surgeon Program. [Accessed June 26, 2013.];Preview of participation. http://www.nqmbc2.org/Surgeon/participation-preview.html.

- 23.The American Society of Breast Surgeons. Official Statements. [Accessed June 26, 2013.];Quality Measures. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for invasive breast cancer. https://www.breastsurgeons.org/statements/QM/ASBrS_Sentinel_lymph_node_biopsy_for_invasive_breast_cancer.pdf.

- 24.Neuner JM, Gilligan MA, Sparapani R, Laud PW, Haggstrom D, Nattinger AB. Decentralization of breast cancer surgery in the United States. Cancer. 2004;101(6):1323–1329. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siminoff LA, Zhang A, Saunders Sturm CM, Colabianchi N. Referral of breast cancer patients to medical oncologists after initial surgical management. Med Care. 2000;38(7):696–704. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200007000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skinner KA, Helsper JT, Deapen D, Ye W, Sposto R. Breast cancer: do specialists make a difference? Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10(6):606–615. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allgood PC, Bachmann MO. Effects of specialisation on treatment and outcomes in screen-detected breast cancers in Wales: cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(1):36–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lovrics PJ, Cornacchi SD, Farrokhyar F, et al. Technical factors, surgeon case volume and positive margin rates after breast conservation surgery for early-stage breast cancer. Can J Surg. 2010;53(5):305–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chagpar AB, Scoggins CR, Martin RC, 2nd, et al. Factors determining adequacy of axillary node dissection in breast cancer patients. Breast J. 2007;13(3):233–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2007.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chagpar AB, Studts JL, Scoggins CR, et al. Factors associated with surgical options for breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2006;106(7):1462–1466. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waljee JF, Hawley S, Alderman AK, Morrow M, Katz SJ. Patient satisfaction with treatment of breast cancer: does surgeon specialization matter? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(24):3694–3698. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.9272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katz SJ, Hawley ST, Abrahamse P, et al. Does it matter where you go for breast surgery?: attending surgeon’s influence on variation in receipt of mastectomy for breast cancer. Med Care. 2010;48(10):892–899. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181ef97df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nattinger AB, Laud PW, Bajorunaite R, Sparapani RA, Freeman JL. An algorithm for the use of Medicare claims data to identify women with incident breast cancer. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(6 Pt 1):1733–1749. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nattinger AB, Pezzin LE, Sparapani RA, Neuner JM, King TK, Laud PW. Heightened attention to medical privacy: challenges for unbiased sample recruitment and a possible solution. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(6):637–644. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The North American Association of Central Cancer Registries, Inc. . [Accessed June 26, 2013.]; http://www.naaccr.org.

- 36.Shea JA, Kletke PR, Wozniak GD, Polsky D, Escarce JJ. Self-reported physician specialties and the primary care content of medical practice: a study of the AMA physician masterfile. American Medical Association. Med Care. 1999;37(4):333–338. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199904000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Medical Association (AMA) [Accessed June 26, 2013.];AMA Physician Masterfile. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/about-ama/physician-data-resources/physician-masterfile.page.

- 38.The Society of Surgical Oncology. [Accessed June 26, 2013.]; www.surgonc.org.

- 39.The American Society of Breast Surgeons. [Accessed June 26, 2013.]; https://www.breastsurgeons.org/

- 40.ICD-9 CM International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision. Millenium edition. 2008. Los Angeles, CA: Practice Management Information Corporation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Current Procedural Terminology: CPT 2004. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 42.HCPCS Health Care Financing Administration Common Procedure Coding System. National Level II Medicare Codes. Millennium edition. 2008. Los Angeles, CA: Practice Management Information Corporation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Association of American Medical Colleges. [Accessed June 26, 2013.];Council of Teaching Hospitals and Health Systems (COTH) https://www.aamc.org/members/coth.

- 44.Nattinger AB, Laud PW, Sparapani RA, Zhang X, Neuner JM, Gilligan MA. Exploring the surgeon volume outcome relationship among women with breast cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(18):1958–1963. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.18.1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Averill RF, Goldfield N, Hughes JS, et al. Healthcare Costs and Utilization Project (HCUP). APR DRG Groups. [Accessed June 26, 2013.];Methodology Overview, Version 20.0. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/APR-DRGsV20MethodologyOverviewandBibliography.pdf.

- 46.Pronovost PJ, Angus DC, Dorman T, Robinson KA, Dremsizov TT, Young TL. Physician staffing patterns and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002;288(17):2151–2162. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.17.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Young MP, Birkmeyer JD. Potential reduction in mortality rates using an intensivist model to manage intensive care units. Eff Clin Pract. 2000;3(6):284–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Du X, Freeman JL, Warren JL, Nattinger AB, Zhang D, Goodwin JS. Accuracy and completeness of Medicare claims data for surgical treatment of breast cancer. Med Care. 2000;38(7):719–727. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200007000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yen TW, Sparapani RA, Guo C, Neuner JM, Laud PW, Nattinger AB. Elderly breast cancer survivors accurately self-report key treatment information. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010;58(2):410–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carlson RW. NCCN breast cancer clinical practice guidelines in oncology: an update. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network: JNCCN. 2003;1 (Suppl 1):S61–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.The American Society of Breast Surgeons. [Accessed June 26, 2013.];Consensus Statement on Guidelines for Performing Sentinel Lymph Node Dissection in Breast Cancer. https://www.breastsurgeons.org/statements/PDF_Statements/SLN_Dissection.pdf.

- 52.Edge SB, Niland JC, Bookman MA, et al. Emergence of sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer as standard-of-care in academic comprehensive cancer centers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(20):1514–1521. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen AY, Halpern MT, Schrag NM, Stewart A, Leitch M, Ward E. Disparities and trends in sentinel lymph node biopsy among early-stage breast cancer patients (1998–2005) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(7):462–474. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rescigno J, Zampell JC, Axelrod D. Patterns of axillary surgical care for breast cancer in the era of sentinel lymph node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(3):687–696. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martelli G, Boracchi P, De Palo M, et al. A randomized trial comparing axillary dissection to no axillary dissection in older patients with T1N0 breast cancer: results after 5 years of follow-up. Ann Surg. 2005;242(1):1–6. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000167759.15670.14. discussion 7–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martelli G, Miceli R, Daidone MG, et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in elderly patients with breast cancer and no palpable axillary nodes: results after 15 years of follow-up. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(1):125–133. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1217-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gillis CR, Hole DJ. Survival outcome of care by specialist surgeons in breast cancer: a study of 3786 patients in the west of Scotland. BMJ. 1996;312(7024):145–148. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7024.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Katz SJ, Hawley ST, Morrow M, et al. Coordinating cancer care: patient and practice management processes among surgeons who treat breast cancer. Med Care. 2010;48(1):45–51. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181bd49ca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ahmed RL, Prizment A, Lazovich D, Schmitz KH, Folsom AR. Lymphedema and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: the Iowa Women’s Health Study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(35):5689–5696. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shih YC, Xu Y, Cormier JN, et al. Incidence, treatment costs, and complications of lymphedema after breast cancer among women of working age: a 2-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(12):2007–2014. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.3517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klabunde CN, Legler JM, Warren JL, Baldwin LM, Schrag D. A refined comorbidity measurement algorithm for claims-based studies of breast, prostate, colorectal, and lung cancer patients. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(8):584–590. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]