Abstract

The apparent sensitivities of several bacterial pathogens to tetracyclines varied by up to 128-fold with the medium content of Fe, but not of other metals. The effect of Fe was independent of superoxide dismutase activity and of intracellular Fe, but accumulation of tetracyclines was blocked in high-Fe medium. Thus, synergistic suppression of bacterial growth in the presence of a low Fe concentration and tetracyclines arises because of elevated antibiotic accumulation.

The tetracyclines (TCs) are broad-spectrum bacteriostatic antibiotics that inhibit the binding of aminoacyl-tRNA to the ribosomal A site, blocking protein synthesis (8). Environmental parameters may modulate the activity of the TCs. For example, MICs are influenced by pH, oxygen concentration, and external cations (1, 11, 16, 19, 21, 23). Such factors are an important consideration when predicting MICs for bacteria isolated from human infections: laboratory-derived MICs may not faithfully reflect antibiotic concentrations that will be effective in vivo. There have been almost no studies to explore the mechanisms by which certain external parameters affect the activity of TCs.

It has been established recently that Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase (Sod1p)-defective mutants of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae are susceptible to oxytetracycline (OTC) via a mechanism that is dependent on oxidative damage (2, 3, 5). This susceptibility could be suppressed with Cu in a Sod1p-independent manner (2). We initiated the present work to investigate whether similar effects occur in prokaryotic cells that are normally sensitive to TCs.

To test whether the sensitivity of Escherichia coli to TCs is copper dependent, the MICs of OTC and TC against E. coli were determined at a range of Cu(NO3)2 concentrations by the agar dilution method (17). The MICs (∼4 μg ml−1 for both antibiotics) were unaffected at up to 3 mM Cu, the highest Cu concentration tested (data not shown).

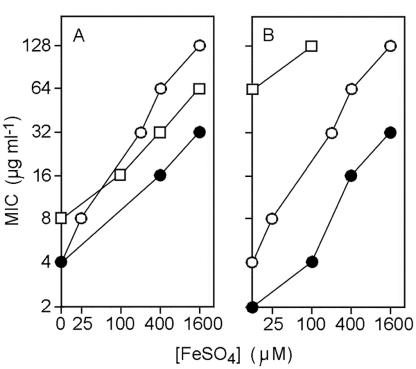

Since OTC can promote oxidative stress (3) and Cu is a Fenton catalyst, we also tested whether Fe influences the sensitivity of E. coli to TCs. The MICs of TC, OTC, and minocycline (MC) were increased markedly by increasing concentrations of FeSO4 in the medium (Fig. 1). Thus, 25 μM FeSO4 rescued E. coli growth at 4 μg of OTC ml−1 and the MIC was increased to 64 μg ml−1 at 400 μM Fe and to 128 μg ml−1 at 1.6 mM Fe (Fig. 1A). The effect of Fe supplementation on the MICs of TC and MC was less marked than for OTC. Nevertheless, eightfold higher TC and MC concentrations were required to inhibit E. coli growth at 1.6 mM Fe than in Fe-unsupplemented Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (≤3 μM Fe) (Fig. 1A). In medium supplemented with the Fe chelator ferrozine (0.5 mM), the MIC of OTC was lowered to 1 μg ml−1 (giving a 128-fold full-range variation in the MIC of OTC in this study) and the MIC of TC was lowered to 2 μg ml−1 (data not shown). Furthermore, ferrozine at 0.5 mM reversed the protective effect of 25 μM FeSO4 against OTC, and protection with 100 μM FeSO4 was reversed at 2.5 mM ferrozine. The effects were relatively specific for Fe, since elevated concentrations of the metal salts CaSO4 and MnSO4 had no discernible effect on OTC activity, while a higher concentration of MgSO4 (100 μM) than of FeSO4 (25 μM) was required to alter the MIC of OTC (data not shown). MgSO4 supplied at up to 0.5 mM did not affect protection by Fe against OTC, even at the lowest Fe concentrations that afforded protection. The antagonism of OTC activity by Fe was also evident in the alternative bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa and particularly in Staphylococcus aureus; for the latter, the OTC sensitivity and Fe-dependent MIC were similar to those for E. coli (Fig. 1B). These results are of particular interest since Fe can be critical for the survival and growth of pathogenic bacteria in mammalian hosts (6). Furthermore, the effect of Fe here was considerably more marked than the about fivefold MIC variation seen in some previous studies of antagonism between Fe and TCs in other microorganisms (11, 19).

FIG. 1.

Activities of TCs in the presence of iron. E. coli, S. aureus, or P. aeruginosa suspensions were pin inoculated into LB agar supplemented with a range of iron (FeSO4) and antibiotic concentrations (the antibiotics were supplied in twofold dilution series). MICs were determined at each FeSO4 concentration as the lowest antibiotic concentrations that resulted in full inhibition of visible growth in replicate incubations. (A) MICs of OTC (○),TC (•), and MC (□) for E. coli GC4468. (B) MICs of OTC for E. coli (○), S. aureus 8325-4 (•), and P. aeruginosa PAO1 (□). These results were reproduced in several independent experiments.

Since superoxide dismutase activity is required for eukaryotic insusceptibility to OTC (3), we hypothesized that any effects of Fe supply on the activity of E. coli Fe superoxide dismutase (encoded by sodB) could explain the above results. However, we found that the MICs for an E. coli sodBΔ single mutant (QC773) and a sodAΔ sodBΔ sodCΔ triple mutant (QC2663) (7) were the same as for wild-type E. coli (data not shown). Furthermore, a furΔ mutant (QC1732) was not affected for OTC sensitivity; fur mutants exhibit diminished sodB expression and are pro-oxidant sensitive (10, 22). These results, together with the fact that Cu did not affect MICs (above), indicate that bacteria are not affected by the oxidative mode of OTC action (3).

Miles and Maskell (15) originally suggested that intracellular Fe chelation by TCs might suppress bacterial growth because of Fe limitation. This suggestion has been taken up elsewhere (11, 19) but has not been rigorously tested. Therefore, we determined the MICs for E. coli mutants defective in ferrous iron uptake (QC2130 [feoBΔ mutant]) and siderophore-mediated ferric iron uptake (H2300 [tonBΔ mutant]) versus those for their isogenic wild types; these mutants exhibit diminished Fe contents under aerobic conditions (22). The MICs of OTC and TC for the mutants (4 μg ml−1) were the same as in wild-type cells, indicating that sensitivity to these antibiotics is not influenced by intracellular Fe content. This conclusion was further supported by the absence of an MIC effect arising from fur deletion (above), as fur (ferric uptake regulation protein) mutants also accumulate high intracellular Fe concentrations (22). Thus, external Fe rather than internal Fe antagonizes the antibacterial activity of TCs.

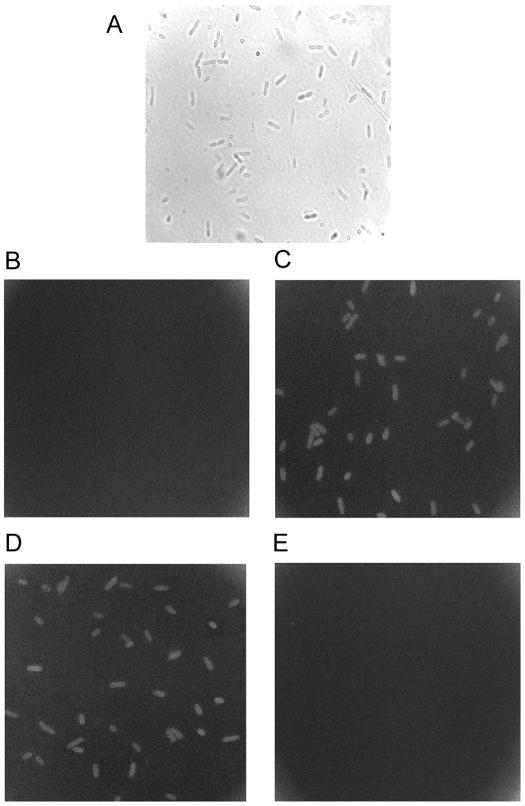

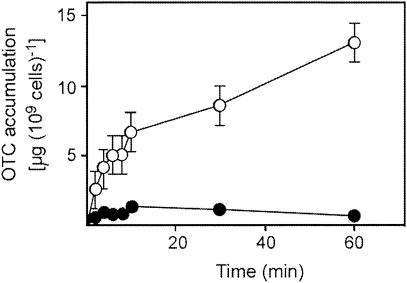

To test whether the effect of Fe on sensitivity to TCs, particularly OTC (Fig. 1), could be due to inhibition of antibiotic uptake, we exploited the availability of convenient OTC assays (9, 12) to examine OTC accumulation. Fluorescence due to the antibiotic (9) was readily observable in cells incubated for 15 min with 64 μg of OTC ml−1 (Fig. 2C); this relatively high OTC concentration was necessary to give a detectable level of short-term OTC uptake. Cu(NO3)2 in the medium had no effect on OTC accumulation (Fig. 2D). In contrast, fluorescence due to OTC accumulation could not be detected when the medium was supplemented with FeSO4 (at FeSO4/OTC ratios comparable to those depicted in Fig. 1) (Fig. 2E). Results for only E. coli are presented in Fig. 2, but essentially the same results were obtained for S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. The E. coli feoB, tonB, and fur mutants exhibited OTC fluorescence similar to that of the wild type (results not shown), indicating that the effect of external Fe could not be attributed to an incidental effect of Fe on the fluorescence properties of OTC. Moreover, we validated the above findings with a quantitative spectrophotometric assay of OTC (3, 12). OTC uptake in non-Fe-supplemented medium continued up to 60 min, giving ∼13 μg of OTC 109 cells−1 (Fig. 3). OTC accumulation was strongly inhibited in the presence of Fe, and after 60 min under these conditions, the cellular OTC content was <10% of that observed in the absence of added Fe (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Qualitative analysis of OTC accumulation in the absence and presence of iron. Exponential-phase E. coli cultures were incubated for 15 min at 37°C and 200 rpm in LB broth in the absence (B) or presence (C to E) of 64 μg of OTC ml−1 and with 50 μM Cu(NO3)2 (D) or 3 mM FeSO4 (E) added. Cellular fluorescence from OTC was visualized under oil immersion with UV excitation with a Zeiss HBO-50/Ac upright fluorescence microscope. A 10× eyepiece and a 100× objective were used for examination. Images were captured with Axiovision 3.0 (Zeiss) software. The phase-contrast light image (A) shows the typical bacterial density in each field of view. Typical results from one of several independent experiments are shown. Similar results were obtained for S. aureus and P. aeruginosa (not shown).

FIG. 3.

Quantitative determination of OTC accumulation in the absence and presence of iron. Exponential-phase E. coli cultures were incubated in LB broth with 64 μg of OTC ml−1 in the absence (○) and presence (•) of 3 mM FeSO4. Samples were removed at intervals, and cells were separated by filtration. Supernatants were retained at 4°C until analysis. OTC in the supernatants was determined spectrophotometrically (3, 12). Cellular OTC accumulation was calculated by subtraction from OTC determinations for control incubations lacking cells. The points are means of three replicate determinations from each of two independent experiments ± the standard errors of the means where these exceed the dimensions of the symbols.

These results, in conjunction with the conclusion (above) that the effects of Fe on TC activity are independent of intracellular Fe, indicate that the Fe dependency of OTC activity arises because of alteration of OTC accumulation. TCs are thought to pass through outer membrane porins OmpC and OmpF of E. coli in a complexed form with a divalent cation (usually [OTC-Mg]+) (20, 21). The chelate is likely to dissociate in the periplasm, yielding uncharged antibiotic, which can diffuse through lipid bilayers and accumulate intracellularly. High Mg concentrations and a high pH would tend to block dissociation of the chelate in the periplasm, thereby inhibiting diffusion across the cytoplasmic membrane (18). Thus, TC accumulation was inhibited by ∼2.5-fold when MgSO4 in the medium was increased from 0 to 9 mM (23). The much greater inhibitory effect of Fe on accumulation described here is likely to relate at least in part to the much higher affinities for TCs of Fe2+ and particularly Fe3+ than Mg2+ (14); note that although Fe was supplied in ferrous form here, Fe(II) is oxidized with time to Fe(III) under aerobic conditions such as those used in our experiments. It is also possible that an [OTC-Fe]2+ complex may be less permeant through the outer membrane porins of E. coli than [OTC-Mg]+. The reason for the greater effect of Fe on OTC activity than on TC and MC activity is unclear since this does not correlate with the antibiotics' relative Fe-binding strengths (13), although the differing polarities of OTC, TC, and MC could provide an explanation (2).

In conclusion, the accumulation and activity of TCs in bacteria were inhibited in the presence of Fe. Such antagonism could explain why Streptomyces aureofaciens conserves TC production activity when Fe is abundant in the medium (4). With regard to TC therapy, it is fortuitous that mammalian Fe concentrations in serum (∼9 to 27 μM) tend to be at the lower end of the range that we found to be particularly antagonistic, particularly considering that much of the Fe in serum will already be bound to transferrin or ferritin. This study further underscores the marked dependency of TC activity on environmental parameters such as Fe, a concern that needs to be addressed also for the new generation of TCs, the glycylcyclines (8).

Acknowledgments

The support of the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM57945) is gratefully acknowledged.

E. coli mutants were a kind gift from Danièle Touati (University of Paris).

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrews, W. H., and L. A. Magee. 1973. Divalent cation reversal of tetracycline-inhibited respiration of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 3:645-646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angrave, F. E., and S. V. Avery. 2001. Antioxidant functions required for insusceptibility of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to tetracycline antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2939-2942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avery, S. V., S. Malkapuram, C. Mateus, and K. S. Babb. 2000. Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase is required for oxytetracycline resistance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 182:76-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bechet, M., and R. Blondeau. 1998. Iron deficiency-induced tetracycline production in submerged cultures by Streptomyces aureofaciens. J. Appl. Microbiol. 84:889-894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackburn, A. S., and S. V. Avery. 2003. Genome-wide screening of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to identify genes required for antibiotic insusceptibility of eukaryotes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:676-681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braun, V. 2001. Iron uptake mechanisms and their regulation in pathogenic bacteria. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:67-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlioz, A., and D. Touati. 1986. Isolation of superoxide dismutase mutants in Escherichia coli—is superoxide dismutase necessary for aerobic life? EMBO J. 5:623-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chopra, I., and M. Roberts. 2001. Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65:232-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Druckheimer, W. 1975. Tetracyclines: chemistry, biochemistry and structure-activity relations. Angew. Chem. 14:721-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubrac, S., and D. Touati. 2002. Fur-mediated transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of FeSOD expression in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 148:147-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grenier, D., M.-P. Huot, and D. Mayrand. 2000. Iron-chelating activity of tetracyclines and its impact on the susceptibility of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans to these antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:763-766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jelikic-Stankov, M., D. Veselinovic, D. Malesev, and Z. Radovic. 1989. Spectrophotometric determination of oxytetracycline in pharmaceutical preparations using sodium molybdate as analytical reagent. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 7:1565-1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jochsberger, J., Cutie, A., and J. Mills. 1979. Differential pulse polarography of tetracycline: determination of complexing tendencies of tetracycline analogs in the presence of cations. J. Pharm. Sci. 68:1061-1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin, R. B. 1985. Tetracyclines and daunorubicin. Metal Ions Biol. Syst. 19:19-52. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miles, A. A., and J. P. Maskell. 1985. The antagonism of tetracycline and ferric iron in vivo. J. Med. Microbiol. 20:17-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nanavaty, J., J. E. Mortensen, and T. R. Shryock. 1998. The effects of environmental conditions on the in vitro activity of selected antimicrobial agents against Escherichia coli. Curr. Microbiol. 36:212-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 4th ed.. Approved standard Mt-A4. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Villanova, Pa.

- 18.Nikaido, H., and D. G. Thanassi. 1993. Penetration of lipophilic agents with multiple protonation sites into bacterial cells: tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones as examples. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:1393-1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pradines, B., C. Rogier, T. Fusai, J. Mosnier, W. Daries, E. Barret, and D. Parzy. 2001. In vitro activities of antibiotics against Plasmodium falciparum are inhibited by iron. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1746-1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schnappinger, D., and W. Hillen. 1996. Tetracyclines: antibiotic action, uptake, and resistance mechanisms. Arch. Microbiol. 165:359-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thanassi, D. G., G. S. B. Huh, and H. Nikaido. 1995. Role of outer membrane barrier in efflux-mediated tetracycline resistance of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:998-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Touati, D., M. Jacques, B. Tardat, L. Bouchard, and S. Despied. 1995. Lethal oxidative damage and mutagenesis are generated by iron in Δfur mutants of Escherichia coli: protective role of superoxide dismutase. J. Bacteriol. 177:2305-2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamaguchi, A., H. Ohmori, M. Kaneko-Ohdera, T. Nomura, and T. Sawai. 1991. ΔpH-dependent accumulation of tetracycline in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:53-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]