Abstract

Background

Several studies have demonstrated the usefulness of medical checklists to improve quality of care in surgery and the ICU. The feasibility, effectiveness, and sustainability of a checklist was explored.

Methods

Literature on checklists and adherence to quality indicators in general medicine was reviewed to develop evidence-based measures for the IBCD checklist: (I) pneumococcal immunization (I), (B) pressure ulcers (bedsores), (C) catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs), and (D) deep venous thrombosis (DVT) were considered conditions highly relevant to the quality of care in general medicine inpatients. The checklist was used by attending physicians during rounds to remind residents to perform four actions related to these measures. Charts were audited to document actions prompted by the checklist.

Results

The IBCD checklist was associated with significantly increased documentation of and adherence to care processes associated with these four quality indicators. Seventy percent (46/66) of general medicine teams during the intervention period of July 2010–March 2011 voluntarily used the IBCD checklist, for 1,168 (54%) of 2,161 patients. During the intervention period, average adherence for all four checklist items increased from 68% on admission to 82% after checklist use (p < .001). Average adherence after checklist use was also higher when compared to a historical control group from one year before implementation (82% versus 50%, p < .0001). In the six weeks after the checklist was transitioned to the electronic medical record (EMR), IBCD was noted in documentation of 133 (59%) of 226 patients admitted to general medicine.

Conclusion

A checklist is a useful and sustainable tool to improve adherence to, and documentation of, care processes specific to quality indicators in general medicine.

BACKGROUND

Medical checklists have received more attention recently.1 Although widely used in other complex industries, their adoption into the field of medicine has been relatively slow.2,3 In recent years, emphasis on reducing complications in surgery and the ICU has led to successful quality improvement (QI) initiatives using checklists.4,5 In contrast, checklists have not received as much attention in general hospital medicine, perhaps because of variable work flow and challenges with identifying appropriate checklist items. Furthermore, a recent review identified significant variability in the design and quality of safety checklists, as well as difficulties in measuring their impact.6 One way that checklists could help improve general hospital care is by increasing adherence to quality indicators. For example, a study of care for vulnerable elders identified as many as 30 quality indicators important to hospitalized patients.7 Moreover, recent studies showed variable rates of adherence to these quality indicators, including discharge planning, venous thromboembolism (VTE) prevention, pain management, evaluation for delirium and dementia, functional screening, and evaluation for pressure ulcers.8,9 Previous QI efforts in our hospital had focused on these issues independently but not collectively, making the adoption of a focused bundled-care checklist an attractive solution.

RATIONALE

Among the long list of important quality indicators in general medicine, pneumococcal immunization, hospital-acquired pressure ulcers (bedsores), catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs), and deep venous thrombosis (DVT)/VTE) stand out as common, measurable quality indicators important to patient safety in the United States.7,8, 10–12 Pneumococcal infection causes more deaths than any other vaccine-preventable infection, approximately half of which could be prevented by pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV).13 It is estimated that 15%–24% of hospitalized patients are diagnosed with pressure ulcers, costing hospitals between $2.2 and $3.6 billion annually.14,15 CAUTIs are the most common nosocomial infections, responsible for approximately 40% of hospital-acquired infections.16 Finally, DVT/VTE is the number one preventable cause of death in hospitals and can occur in up to 60% of patients without prophylaxis.17

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) no longer reimburses hospitals for treating certain hospital-acquired conditions considered reasonably preventable,18 which includes advanced stage hospital-acquired pressure ulcers, CAUTIs, and hospital-acquired DVTs.11 In addition, administering pneumococcal vaccination for patients with pneumonia is a publicly reported hospital quality measure.19

Given the clinical significance and financial implications of these conditions, a QI team consisting of two hospitalists and one quality leader was formed to develop and test an inpatient checklist at the University of Chicago Medical Center (UCMC). Specifically, a paper checklist was designed to address the following four evidenced-based care processes7,14,16,17,20:

Pneumococcal vaccination for eligible patients

Heel and sacrum skin exams for patients at high-risk for pressure ulcers

Prompt removal of urinary catheters from patients when appropriate

Administering pharmacologic DVT prophylaxis for all eligible patients

We aimed to apply the lessons learned in previous checklist projects to assess the feasibility, effectiveness, and sustainability of using a checklist for common inpatient conditions in adult general medicine patients. Our specific study question was whether a checklist designed to remind physicians to complete clinical care tasks associated with four inpatient quality measures was associated with improved adherence to these care processes.

METHODS

Ethical Issues

This study was deemed exempt from the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board.

Setting

UCMC is a 596-bed tertiary care facility and the largest academic medical center on the South Side of Chicago. General medicine inpatient teams consisted of the attending physician plus one or more residents, interns, medical students, and pharmacists.

Planning the Intervention

The initial phase of the intervention focused on creating an inpatient care checklist. In April 2010, three faculty members [V.M.A., E.M.S., A.M.D.] met to review potential candidate conditions. Materials from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and CMS were reviewed.21,22 The faculty members designed a paper-based checklist on the basis of methods outlined in Gawande’s The Checklist Manifesto and other published literature.3, 23–25 Initially, they evaluated nine conditions for inclusion in the checklist, but concerns regarding checklist burden and information overload led to the reduction to four items, with a focus on conditions that were most frequent, relevant, easy to apply, and linked to reimbursement. As described earlier, pneumococcal immunization (I), pressure ulcers (bedsores) (B), CAUTI (C), and DVT (D) were selected as most pertinent to general ward patients, and the acronym “IBCD” was used to represent these conditions (Figure 1, page 149). Conditions not included were: delirium, nutritional status, falls, hyperglycemia and end-of-life care. Also, stress ulcer prophylaxis was not included because of previous work at our institution that highlighted its overuse and a recent QI intervention targeting that area.26

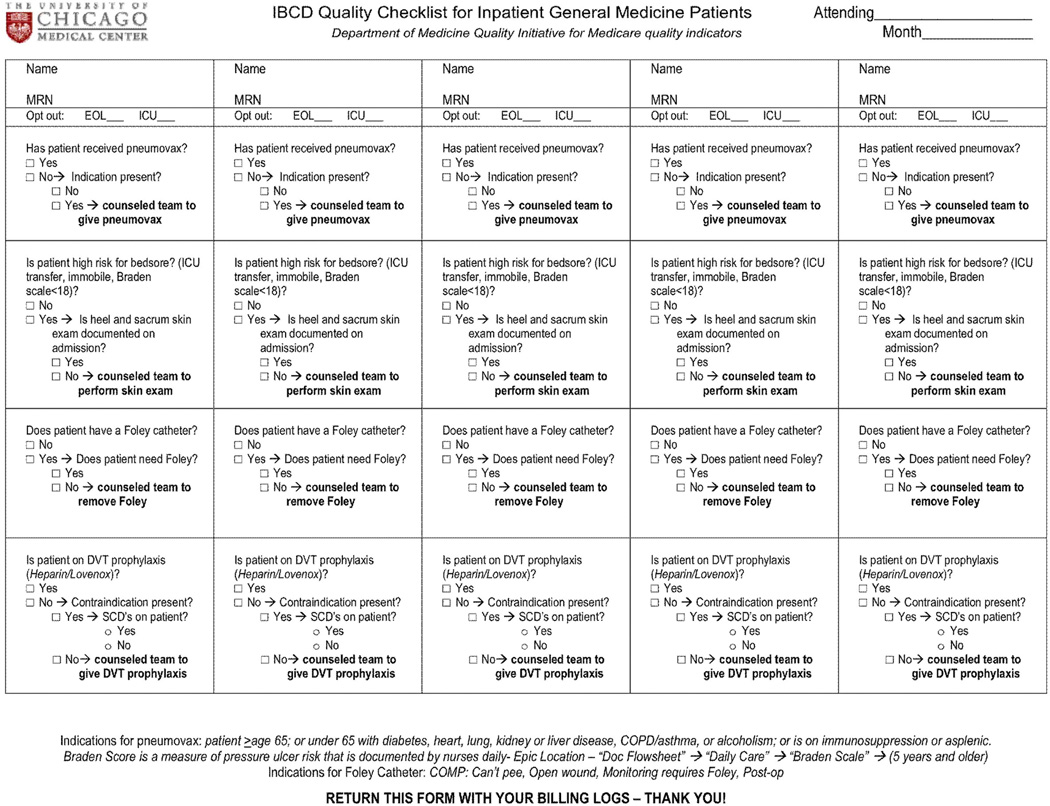

Figure 1.

The paper checklist was designed to mimic billing logs (with multiple patients on one page), and attending physicians were instructed to verbalize and record checklist items with the rest of the team during postcall rounds. Pneumovax is referred to as a pneumococcal polysaccharide in the text. MRN, medical record number; EOL, end of life; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; SCD, sickle cell disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Next, it was necessary to determine who should complete the checklist. Given the influential role of attending physicians as leaders of the medical-team, we believed that the intervention would be most effective if attendings completed the checklist. Although we considered alternatives, previous experience at our institution demonstrated that attendings were the key champions for adoption of QI interventions.27 Second, to accommodate the variable work flow of inpatient medicine, the checklist was constructed in a “do-confirm” format (in which tasks are completed during normal work flow and subsequently reviewed).3

The checklist was integrated into the established routine of postcall morning rounds for new admissions. This is an opportune time to review the four safety conditions, as it is when the team first presents information about newly admitted patients to the attending physician. Thus, the checklist verifies whether appropriate care processes have been completed and prompts the team to complete unfinished tasks. All questions on the checklist refer to evidence-based processes or eligibility status for the conditions and require a “yes” or “no” response. Each item was to be verbalized and assessed by the team, and the checklist was to be completed once for each new patient. Although postcall rounds may seem like a hurried time in which to integrate the checklist, the burden of attending documentation during postcall rounds is lowest. Because many attendings also use this time to enter the patient’s name and medical record number into his or her billing log, we designed the checklist to mimic the billing log and asked attendings to turn in checklists with their billing logs.

Two attending physicians [V.M.A., E.M.S.] pilot-tested an initial version of the checklist at the UCMC with their general medicine teams in May 2010. Trained research assistants [G.E.K., K.L.S.] observed rounds, collected checklists, and performed chart audits to assess the impact of the intervention on physician documentation. On the basis of feedback from the pilot study, the initial checklist was amended to add two opt-out criteria: (1) patients near the end of life and (2) unstable patients who will be transferred to the ICU. In both of these cases, the checklist conditions were not considered high priority and may result in inappropriate care.

In July 2010, all four general medicine teams were invited during two required orientation meetings (one for attendings and one for residents) to use the IBCD checklist. At the attending orientation, the project was explained by quality leader [A.M.D.] with support of department leaders (Department of Medicine Chair, Internal Medicine Residency Program Director, Chief Resident). Each team received (1) checklists for newly admitted patients, (2) educational pocket cards for residents and medical students, and (3) a handout for teaching rounds (Figure 1, Figure 2 [above]). Attending physicians were given a packet containing these materials, including an instruction sheet detailing the purpose of the project and directions for completing the checklist. At the resident orientation, a brief teaching presentation was made about the importance of these conditions and how attendings would use the checklist. These presentations were made every month during the intervention period, and a reminder email was sent halfway through each month to remind teams of the initiative. In addition, signs were posted in the resident workroom and hospital hallways reminding teams to complete their “IBCDs.”

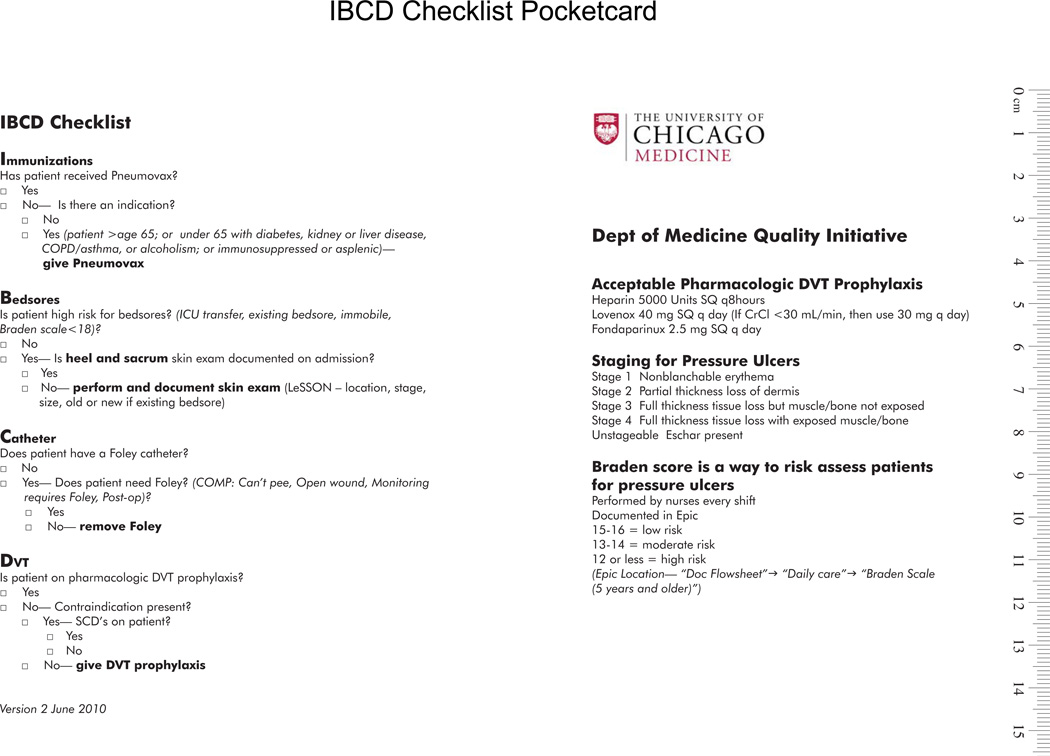

Figure 2.

The IBCD checklist was printed on laminated pocket cards and distributed to general medicine residents as a reference tool. In addition to the checklist, the pocket card contains information regarding deep venous thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis and pressure ulcer staging, as well as references to additional resources. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SCD, sickle cell disease; SQ, subcutaneous.

In May 2011, the IBCD checklist was incorporated into our institution’s vendor-provided electronic medical record (EMR), replacing the paper version. The electronic version of the checklist consisted of a preformed template mirroring the paper checklist in the format of “yes” or “no” questions. After the checklist is completed, the assessment and plan portion of the admission note is automatically populated based on the responses. In addition, residents had the option of using an IBCD smartphrase (a macro that produces prompts in the documentation for the care processes the checklist is intended to promote) or writing IBCD freehand as an item in their assessment (Appendix 1, available in online article).

Planning the study of the intervention

Attending physicians were instructed to turn in completed checklists, and trained research assistants [A.V.A., G.E.K., K.L.S.] recorded checklist responses as a baseline measure of adherence to the four processes of interest. The research assistants were also trained on how to conduct chart reviews to confirm completion of tasks prompted by the checklist.

Methods of evaluation

The research assistants conducted chart reviews of all patients admitted to general medicine in the July 2010– March 2011 period (months 1–9 after full implementation) for whom a checklist was used. Completion of checklist items was determined by reviewing EMRs and scanned copies of physician notes in a medical record–viewing program. Evidence-based indications for pneumococcal vaccination, high-risk status for pressure ulcers, indications for urinary catheters, and contraindications for DVT prophylaxis were followed to validate data entered on the checklist.7,14,16,17,20 Patient charts were audited from May 15, 2011 through June 30, 2011 (10–11 months after full implementation and the first two months of EMR implementation) to determine utilization and sustainability of the electronic version of the checklist. Patient charts from July 2009 through April 2010 (1 year before the intervention to one month before the pilot study) were audited as part of an ongoing research study of hospitalized patients to yield a comparison historical control group.

In the case of immunizations, data provided on the checklist were used to calculate the percentage of eligible patients who had already received pneumococcal vaccination and the percentage of eligible patients who needed it. To determine whether the PPSV was actually offered, we looked for an order in the EMR during the hospitalization of interest. For bedsores, data on the checklist was used to determine the percentage of patients who were at high risk for bedsores for whom a heel and sacrum skin examination was documented on admission and the percentage of high risk patients who needed one. To confirm skin examinations, we looked for physician documentation of “pressure ulcers/bedsores” or more specific notation of heel or sacrum skin examination in the medical chart. For urinary catheters, data on the checklist were used to determine the percentage of catheterized patients with a proper indication for a urinary catheter and percentage of patients without a proper indication. Removal of catheter within 24 hours after admission was verified by examining orders in the EMR. For DVT prophylaxis, data on the checklist were used to determine the percentage of eligible patients receiving DVT prophylaxis on admission and percentage of patients needing it. Appropriate DVT prophylaxis (for example, heparin, enoxaparin) was confirmed by examining the medication history in the EMR, including patients already receiving therapeutic anticoagulation.

For the historical control group, we conducted chart reviews to determine adherence to the four quality measures of interest. For immunizations we included all patients with a documented indication for the PPSV who did not have previous documentation of its administration. Next, patients with a Braden Scale score < 18 were considered to be at high risk for pressure ulcers.28 We then reviewed the medical chart for documentation of a skin examination with specific notation of pressure ulcer or bedsore. For urinary catheters, we reviewed the charts of all patients with documented Foley catheters for specific notation of an indication to determine which catheters were indicated. Finally, all patients without documentation of a specific contraindication and not already on therapeutic anticoagulation were considered eligible for DVT prophylaxis.

Data Analysis

We used a two-sample test of proportions to compare the percentage of quality metrics met before the checklist (initial quality score on admission) with the percentage met after the checklist (total quality score). Statistical analysis was completed using Stata 11.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas); p < .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Use of the Checklist During the Implementation Period

During the implementation period of July 2010-March 2011, 70% (46/66) of general medicine attendings used the IBCD checklist (Figure 1), with 1,168 (54%) of the 2,161 patients admitted to general medicine. Of the 1,168 patients for whom a checklist was completed, 33 patients were either opt-out because of end of life or transferring to ICU or because of the unavailability of their medical records. Attending participation varied from month to month, but variation was not significant (Χ2 = 8.37, p = .40).

Adherence to Process Measures

Figure 3 (page 152) demonstrates the improvements in adherence to each process measure, as determined on admission compared with after checklist use. Use of the checklist was associated with 301 actions and an increase in average adherence to the four quality measures from 68% (1,512/2,209) to 82% (1,813/2,209), p <.001.

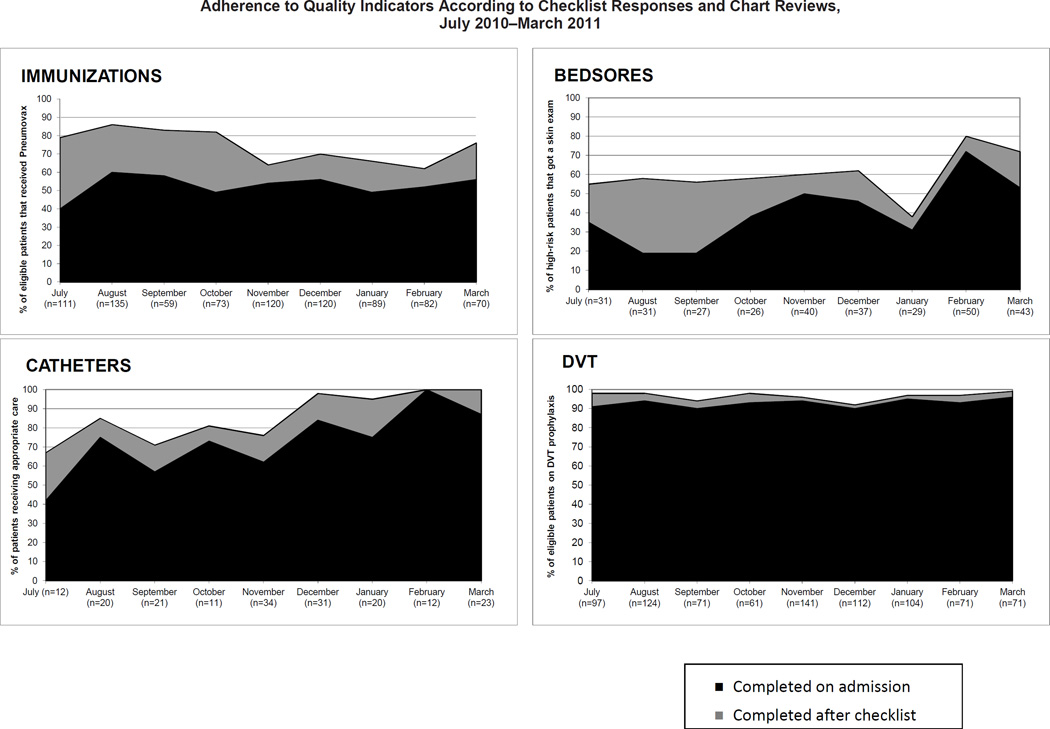

Figure 3.

Adherence, as calculated from data entered on the checklist, was determined by measuring evidenced-based care processes specific for each quality indicator: 1. Pneumococcal vaccination for eligible patients; 2. Heel and sacrum skin exams for patients at high risk for pressure ulcers; 3. Documentation of indication for urinary catheter and prompt removal of urinary catheters from patients without an indication; and 4. Administering pharmacologic DVT prophylaxis to any patient without a contraindication. Actions prompted by the checklist were confirmed by chart review and added to the initial responses entered on the checklist to derive a total quality score.

Forty-eight percent of the eligible patients had not yet received pneumococcal vaccination on admission. Checklist use was associated with 190 PPSV immunizations, increasing the average adherence from 52% on admission to 74% after checklist use (p < .001). For pressure ulcers, 56% of the patients at high risk for bedsores had not received a skin examination on admission. The checklist was associated with administration of a skin examination to 57 of the 177 patients at high risk for bedsores who had not received an examination, increasing adherence from 44% to 62% (p < .001). The checklist was also associated with an improvement in appropriate use of urinary catheters. Seventy-three percent of patients had a Foley with an appropriate indication at baseline. The checklist prompted its removal in 28 patients without an indication, increasing adherence to 86% (p < .001). While DVT prophylaxis was high on admission before checklist use (93%), checklist use was associated with near-universal prophylaxis (96%, p < .01).

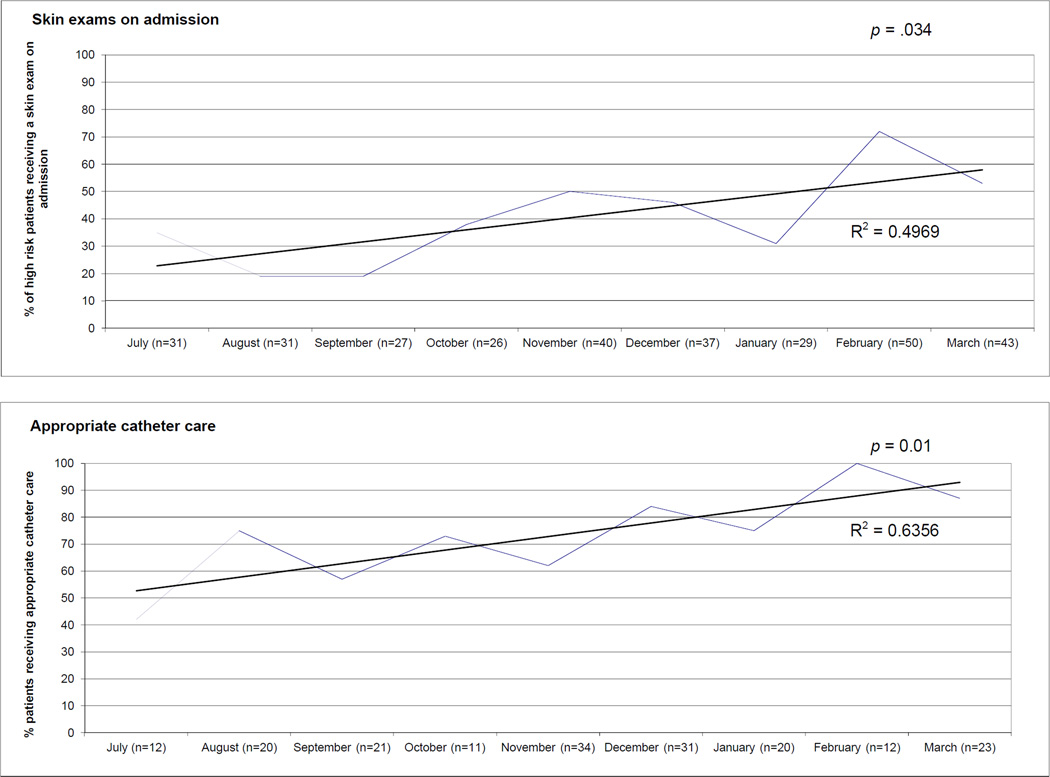

In addition to the improvements after checklist use, there was a greater adherence to all four process measures on admission even before prompting from the checklist, indicating that these care processes were becoming more standard practice (Figure 4, page 153). This learning effect was only significant for bedsores (p = .034) and catheters (p = .01). Evidence for a learning effect was also present in chart reviews showing the acronym “IBCD” in residents’ admission notes (Appendix 1), demonstrating improved awareness and documentation of these conditions.

Figure 4.

As the intervention progressed, a greater percentage of patients began receiving the recommended care on admission and before use of the checklist. On admission, more patients received skin examinations if at high risk for pressure ulcers (p = .034) and had their Foley catheter discontinued if the catheter was not indicated (p = .01) than when the intervention started.

Soon after the intervention began, one resident reported that the PPSV was coded as “PRN” in the EMR, meaning that patients would have to request the vaccination to receive it. Thus, this initiative helped identify a problem with ordering immunizations, which was brought to the attention of senior leadership. Also, one team reported going on regular “ulcer rounds” to examine patients for pressure ulcers. Finally, some attendings began “handing off” extra checklists and explaining the initiative to the next attending taking over their service, demonstrating ownership of the checklist.

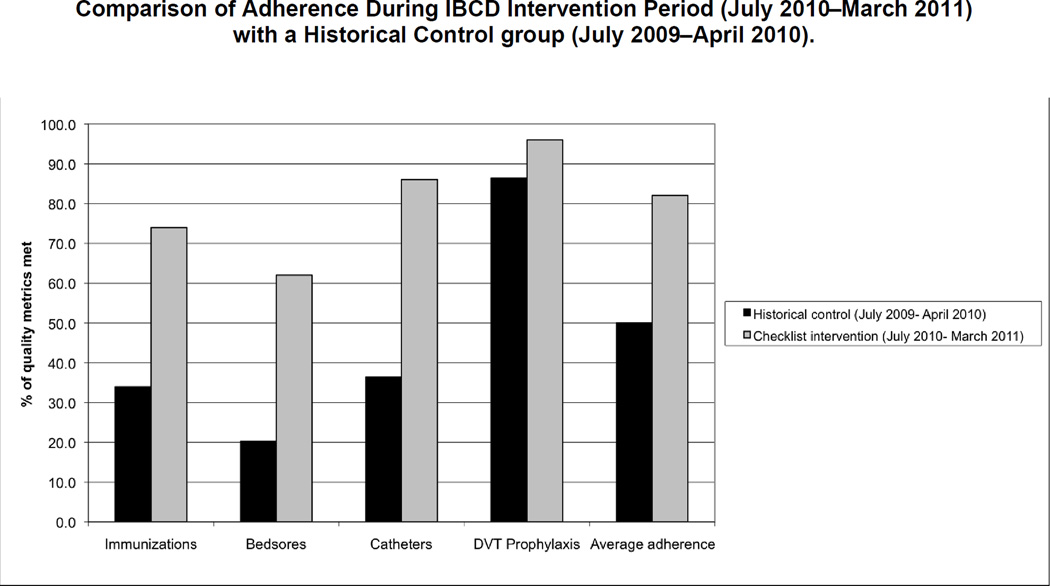

Compared with the historical control group, average adherence for all four measures was significantly improved. From July 2009 through April 2010 (one year before the checklist intervention to one month before the pilot study), 34% (479/1,399) of the eligible patients had either previously received a PPSV or it was ordered for them before discharge, compared with 74% (639/859) during the intervention period (p < .0001). Similar results were seen for the other three measures. Average adherence to the four quality metrics in the control group was 50% (1,702/3,430), compared with 82% (1,813/2,209) during the intervention period (p < .0001) (Figure 5, page 154).

Figure 5.

Adherence was determined by measuring evidenced-based care processes specific for each quality indicator: 1. Pneumococcal vaccination for eligible patients; 2. Heel and sacrum skin exams for patients at high risk for pressure ulcers; 3. Documentation of indication for urinary catheter and prompt removal of urinary catheters from patients without an indication; and 4. Administering pharmacologic DVT prophylaxis to any patient without a contraindication. DVT, deep venous thrombosis.

IBCD Documentation

After the implementation of the IBCD checklist in the EMR, IBCD documentation was noted in the charts of 133 (59%) of 226 patients admitted to general medicine from May 15, 2011 through June 30, 2011. Of those 133 patient charts, 28 (21%) featured the template version of the checklist; 58 (44%) featured the IBCD smartphrase, with additional responses (“free text”) filled in; and 47 (35%) featured “IBCD” as a freehand note at the end of the assessment and plan (Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

The IBCD checklist was associated with significantly increased adherence to care processes regarding (I) pneumococcal immunization, (B) pressure ulcers (bedsores), (C) CAUTIs, and (D) deep venous thrombosis/venous thromboembolism. During the intervention period, average adherence to these four domains increased from 68% on admission to 82% after checklist use. The intervention was sustained with 70% (46/66) of attendings participating during the intervention period, with no statistically significant variation from month to month. The majority of teams voluntarily used the checklist and incorporated it into their work flow without difficulty. The historical control group had very low levels of adherence to the quality measures, compared with the IBCD intervention group. Overall, this QI initiative attempted to build on the work of other successful initiatives using checklists and yielded similar results.4,5,29,30

Alternatives to increasing adherence to these quality metrics have been explored, such as EMR reminders with performance feedback for DVT prophylaxis or VTE prophylaxis protocols.31,32 One advantage of the checklist approach is the ability to focus on multiple aspects of care rather than targeting a single intervention. Furthermore, the improvements in this study and other checklist studies tend to be higher than interventions using EMR reminders.

In May 2011, we transitioned from having attendings complete the paper IBCD checklist to asking residents to complete an IBCD template in the EMR as part of their risk assessment when writing their admission history and physical. An important aspect of this change was that ownership of the checklist transitioned from the attending to the resident. IBCD was documented in the EMR for most patients admitted to general medicine during the first month of implementation, although the template was infrequently used. Although this is reassuring regarding the continued use of the IBCD paradigm by residents, the high use of free text or the smartphrase resulted in lower-quality documentation than when the template was used. For example, the catheter section of the smartphrase may have been recorded as “Foley to gravity” without documentation of whether an indication was present. Incorporating documentation of indications/contraindications and linking the template to order sets may help IBCD contribute to meaningful use of the EMR. Another concern regarding the use of the electronic checklist was the loss of “teachable moments” between the attending and resident when a paper checklist is used. It is possible that the authority of the attending and the opportunity for teaching with the paper checklist contributed to the learning trends seen for bedsores and catheters. Overall, use of IBCD by residents after the transition to the EMR remained high.

The greatest improvements in care were seen for immunizations, pressure ulcer examinations, and Foley catheter care, partly because those were the clinical areas with lower baseline adherence. In fact, significant learning trends were seen for pressure ulcer prevention and appropriate catheter use (Figure 4). In contrast, because the rate of DVT prophylaxis was high at baseline, there was little room for improvement. Future checklist efforts may benefit by targeting the lowest-performing areas. Furthermore, it may be important to have flexibility with checklist items for targeting of areas with the greatest potential for improvement and for responding to changes in practice guidelines (for example, changes in guidelines for DVT prophylaxis for medical patients).

For immunizations, even though hospitalization is often a missed opportunity for pneumococcal vaccination,33 some attendings reported that they still considered preventive immunization more appropriately performed in the outpatient setting. In addition, providers may also be hesitant to administer immunizations when patients have an uncertain vaccination history despite evidence that repeat dosing with the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine is safe.34 Finally, patients who were offered the vaccine but refused may not have a documented refusal in their chart, making the quality measure failure one of documentation not actual quality of care.

To help determine why attending participation varied, the investigators contacted users and nonusers regarding barriers to adoption of the checklist in person and via email. Adopters reported that it was easy to use and integrated it into their work f low. Nonadopters often reported high clinical workload and less familiarity with inpatient medicine, so that the checklist became “extra work” on top of a busy service. A checklist can be perceived as burdensome, especially when items on the checklist are duplicated within existing checklists, there is no perceived benefit for the time spent completing the checklist, poor communication between checklist users interferes with productivity, and ambiguity in the checklist causes confusion.35 This highlights the need to streamline the checklist and limit the burden on the users by targeting the areas with lowest baseline adherence and using templates in the EMR. Further exploration of barriers to checklist use remains an area of future study.

Limitations

There are some limitations to the IBCD checklist. Because it was not completed at the patients’ bedside, there was a gap between completing the checklist and providing care. To streamline this process, the checklist was integrated into the EMR, enabling physicians to make orders as they are completing it. Although teams have found it easier to use the smartphrase compared to the template, the adequacy of documentation is in question. As a result, we are working on a revised IBCD smartphrase that prompts for various fields (for example to document indication for a urinary catheter if one is present). Because of the heavy workload of inpatient medicine, “checklist fatigue” is another valid concern. Therefore, it is essential that checklists make delivering care easier and timely.

Because this intervention occurred at a single institution, generalizability of the results is limited. Also, we did not measure patient outcomes, adjust for the severity of patients’ illnesses, or include a control hospital. At a single institution, outcome data for adverse events such as a CAUTI were small, making it difficult to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of the intervention in preventing adverse outcomes. However, to determine if our intervention had the unintended consequence of changing the rate of stress ulcer prophylaxis with H2 blockers, we looked at billing data from the year before our intervention for hospitalized patients not admitted to the ICU and without an admission diagnosis of a gastrointestinal bleed but found no change in rates. We chose stress ulcer prophylaxis because it is a physician decision to administer, and the target of the checklist was also physicians. This provides some reassurance that our intervention did not have unintended consequences in other areas.

Given the relatively small sample size and frequent communication between general medicine teams, a randomized controlled trial at a single institution would have been difficult to conduct. Instead, we conducted an intention-to-treat analysis to determine whether improvement occurred from the initial time of admission to after completing the checklist on morning rounds. Therefore, it is not necessarily clear whether the increased rates of adherence were due to the checklist itself or other factors. For example, it is likely that the educational components of the program and impact of the checklist on patient safety culture encouraged better clinical practices. A historical control group was chosen as a measure of baseline adherence to these metrics for comparison to the intervention period. A concurrent control group of checklist nonusers was not favored because this nonrandom group may have been suspect to selection bias. For example, those attendings who chose to use the checklist may have been higher performers in the quality metrics compared to those who did not.

Regarding the methods of analysis, there are some inherent limitations to using chart reviews to measure adherence because the patient chart is not necessarily a complete representation of all care provided during a patient’s hospitalization.36 For example, it is possible that the low rates of adherence in the historical control group were partially a result of poor documentation in the medical record. However, chart documentation is a frequently used method to measure quality and is often a target of QI efforts. Finally, because this study only focused on process measures, future efforts will need to examine outcomes to determine whether the checklist is associated with reduced adverse events.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that a comprehensive intervention using a checklist on a general inpatient medicine service can increase adherence and documentation of common care processes measures. Our intervention was associated with statistically significant improvements in PPSV administration, skin examinations to prevent pressure ulcers, appropriate Foley catheter care, and DVT prophylaxis. It is possible that the improved adherence to these care processes could help reduce costly and preventable adverse outcomes such as stage III and IV pressure ulcers and CAUTIs. Future work includes exploring opportunities to expand to other institutions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Acknowledgments

This study was funded through the National Institute on Aging Short-Term Aging-Related Research Program (T35AG029795), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Centers for Education and Research on Therapeutics (1U18HS016967-01), The University of Chicago Innovations in Infection Prevention Award (IIPA), and the Pritzker Summer Research Program. Prior presentations on this data include Institute of Healthcare Improvement 2010 Annual Conference in Orlando, FL. The authors acknowledge Jim Woodruff, MD, Director of Internal Medicine Residency, University of Chicago; Roy Weiss, MD, PhD, Executive Vice Chair, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago; general medicine chief residents, University of Chicago; and Meryl Prochaska.

Contributor Information

Anthony V. Aspesi, Medical Student in the Quality and Safety Scholarship & Discovery Track, Pritzker School of Medicine, University of Chicago..

Greg E. Kauffmann, Medical Student in the Quality and Safety Scholarship & Discovery Track, Pritzker School of Medicine, University of Chicago..

Andrew M. Davis, Associate Professor and Director of Quality, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago..

Elizabeth M. Schulwolf, Assistant Professor and Interim Program Director, Division of Hospital Medicine, Loyola University Stritch School of Medicine, Maywood, Illinois..

Valerie G. Press, Assistant Professor, Section of Hospital Medicine, University of Chicago..

Kristen L. Stupay, formerly Research Assistant, is a Medical Student, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans..

Janey J. Lee, undergraduate Political Science Student, University of Chicago.

Vineet M. Arora, Associate Professor and Associate Program Director, Internal Medicine Residency Program, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, and a member of The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety’s Editorial Advisory Board..

References

- 1.Davidoff F. Checklists and guidelines: Imaging techniques for visualizing what to do. JAMA. 2010 Jul 4;304(2):206–207. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hales BM, Pronovost PJ. The checklist: A tool for error management and performance improvement. J Crit Care. 2006;21(3):231–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gawande A. The Checklist Manifesto. New York City: Metropolitan Books; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pronovost P. Interventions to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU: The keystone intensive care unit project. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36(10):S171, e1–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haynes AB, et al. Safe Surgery Saves Lives Study Group. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009 Jan 29;360(5):491–499. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0810119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ko HC, Turner TJ, Finnigan MA. Systematic review of safety checklists for use by medical care teams in acute hospital settings: Limited evidence of effectiveness. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011 Sep 2;11 doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arora VM, McGory ML, Fung CH. Quality indicators for hospitalization and surgery in vulnerable elders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(Suppl 2):S347–S358. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arora VM, et al. Using assessing care of vulnerable elders quality indicators to measure quality of hospital care for vulnerable elders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(11):1705–1711. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahlstrom M, et al. Improving identification and documentation of pressure ulcers at an urban academic hospital. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37(3):123–130. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37015-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carpenter D. Never land: Medicare declares 'no pay for preventable errors'. Trustee. 2008 Mar;61(3):12, 6, 21, 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattie AS, Webster BL. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services' "never events": An analysis and recommendations to hospitals. Health Care Manag. 2008;27(4):338–349. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0b013e31818c8037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kizer KW, Blum LN. Safe practices for better health care. Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation (Vol 4: Programs, Tools, and Products) Rockville MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); 2005. Feb. [Accessed Feb 22, 2013]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK20613/pdf/ch3.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuomanen EI, Hibberd PL. [Accessed Feb 22, 2013];Pneumococcal Vaccination in Adults. 2011 Jun 8; http://www.uptodate.com/contents/pneumococcal-vaccination-in-adults?source=search_result&search=pneumococcal+vaccination&selectedTitle=1%7E150.

- 14.Dharmarajan T, Ahmed S. The growing problem of pressure ulcers: Evaluation and management for an aging population. Postgrad Med. 2003;113(5):77–88. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2003.05.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whittington KT, Briones R. National prevalence and incidence stud: 6-year sequential acute care data. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2004;17(9):490–494. doi: 10.1097/00129334-200411000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hooton TM, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(5):625–663. doi: 10.1086/650482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geerts WH, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition) Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):381S–453S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) [Accessed Feb 22, 2013];Hospital-Acquired Conditions (Present on Admission Indicator). Updated Sep 20, 2012. Accessed http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HospitalAcqCond/index.html?redirect=/hospitalacqcond.

- 19.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed Feb 22, 2013];Hospital Compare. Updated Feb 1, 2013. http://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/.

- 20.Bratzler DW, et al. Failure to vaccinate Medicare inpatients: A missed opportunity. Arch Intern Med. 2002 Nov 11;162(20):2349–2356. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Office of Public Affairs. [Accessed Feb 22, 2013];Eliminating Serious, Preventable, and Costly Medical Errors: Never Events (News Release) 2006 May 18; (Updated Dec 2, 2011). https://www.cms.gov/apps/media/press/release.asp?Counter=1863.

- 22.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed Feb 22, 2013];National Quality Measures Clearinghouse. doi: 10.1080/15360280802537332. http://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Hales B, et al. Development of medical checklists for improved quality of patient care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008;20(1):22–30. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scriven M. The Logic and Methodology of Checklists. Western Michigan University: The Evaluation Center; 2000. Jun, [Accessed Feb 22, 2013]. (revised Oct 2005, Dec 2007). http://www.wmich.edu/evalctr/archive_checklists/papers/logic&methodology_dec07.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verdaasdonk EG, et al. Requirements for the design and implementation of checklists for surgical processes. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(4):715–726. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liberman JD, Whelan CT. Brief report: Reducing inappropriate usage of stress ulcer prophylaxis among internal medicine residents. A practice-based educational intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(5):498–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arora VM, et al. Improving inpatients' identification of their doctors: Use of FACE cards. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009;35(12):613–619. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(09)35086-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyder CH, et al. The Braden Scale for pressure ulcer risk: evaluating the predictive validity in Black and Latino/Hispanic elders. Appl Nurs Res. 1999 May;12(2):60–68. doi: 10.1016/s0897-1897(99)80332-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hewson KM, Burrell AR. A pilot study to test the use of a checklist in a tertiary intensive care unit as a method of ensuring quality processes of care. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2006;34(3):322–328. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0603400222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pronovost P, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006 Dec 28;355(26):2725–2732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kucher N, et al. Electronic alerts to prevent venous thromboembolism among hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 2005 Mar 10;52(10):969–977. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maynard G, Stein J. Designing and implementing effective venous thromboembolism prevention protocols: Lessons from collaborative efforts. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2010;29(2):159–166. doi: 10.1007/s11239-009-0405-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu P, Nuorti J. Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination among adults aged 65 years and older, U.S., 1989–2008. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(4):287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hammitt L, et al. Repeat revaccination with 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine among adults aged 55–74 years living in Alaska: No evidence of hyporesponsiveness. Vaccine. 2011;29(12):2287–2295. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fourcade A, et al. Barriers to staff adoption of a surgical safety checklist. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(3):191–197. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luck J, et al. How well does chart abstraction measure quality? A prospective comparison of standardized patients with the medical record. Am J Med. 2000;108(8):642–649. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.