Abstract

In a recent article in the Reader’s Opinion, advantages and disadvantages of the certification processes of interrupted Chagas disease transmission (American trypanosomiasis) by native vector were discussed. Such concept, accepted by those authors for the case of endemic situations with introduced vectors, has been built on a long and laborious process by endemic countries and Subregional Initiatives for Prevention, Control and Treatment of Chagas, with Technical Secretariat of the Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization, to create a horizon target and goal to concentrate priorities and resource allocation and actions. With varying degrees of sucess, which are not replaceable for a certificate of good practice, has allowed during 23 years to safeguard the effective control of transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi not to hundreds of thousands, but millions of people at risk conditions, truly “the art of the possible.”

Keywords: Chagas disease, vector control, interruption of transmission, certification, human infection, prevention

In the Reader’s Opinion section of the magazine Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, published in Rio de Janeiro in April 2013 ( 108 : 251-254), there is an article written by Fernando Abad-Franch et al., where the advantages and disadvantages of the certification processes for the interruption of the transmission of Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis) by native vectors are discussed. With regard to this, the authors of this article would like to enrich the analysis through the contributions that will follow.

Between 1991-1992 the Southern Cone Initiative (INCOSUR) was implemented to eliminate Triatoma infestans and interrupt the transmission via transfusions of American trypanosomiasis (INCOSUR/Chagas). This brought upon the Pan American Health Organization/Word Health Organization (PAHO/WHO) the role of Technical Secretariat, which added to their responsibilities the duty to offer support and coordination, in an international South to South cooperation scheme among countries, which originally implemented the following objectives ( INCOSUR 1991 ): (i) elimination of T. infestans from all households and their surroundings in endemic areas, as well as areas considered “probably endemic”, (ii) reduction and elimination of domestic infestations of other triatomine species present in the same zones occupied by T. infestans and (iii) reduction and elimination of transmission via blood transfusions by improving blood bank networks and strengthening the selection process of efficient donors.

These goals, theoretically feasible to be achieved in the medium and long term, assuming the existence of resources which were never available in quality or quantity for INCOSUR/Chagas or any other of the Subregional Initiatiaves (Initiative of the Countries of Central America for Control of Vector-Borne and Transfusional Transmission and Medical Care for Chagas Disease-1997; Andean Initiative for Chagas Disease Control-1998) ( OPS 1998 , 2004 ), evolved into a target image that constituted a genuinely “virtual horizon” of potential expectations.

Between 1992-1999 ( WHO 1998 , 1999 ), the work objectives for the control of the disease were reconsidered by the countries, based on what at that moment they considered documented significant progress in Chagas control. Fundamentally these advances were made through vector control and the universal screening of blood donors as seen by achievements demonstrated mainly in Uruguay, Chile and Brazil.

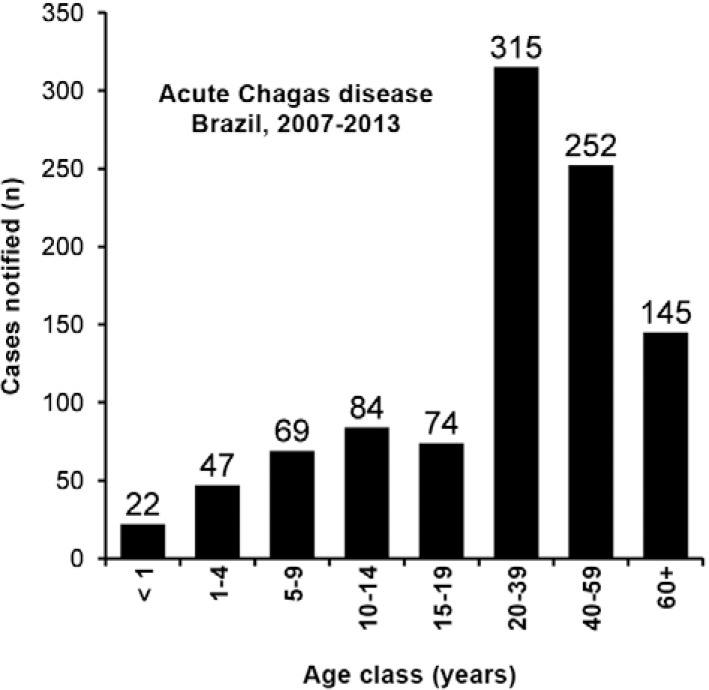

It was through these developments that the concept of “interruption of the vector transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi ” ( OPS 2002 , 2010 ), was first considered based on three concepts that are applied in a determined geographical context: (i) prevalence of the trypanosome infection in pre-school and school age children, intended to reflect the effective activity or inactivity of recent transmission, using values less than 2% in children between zero-five years of age as a base indicator; (ii) absence of clinical (or subclinical) evidence of acute Chagas cases, notified to the national health system of each country, assuming that the presence of one reported case in the last three years equals a diagnosis of an active transmission of T. cruzi in the area. It is important to note that the diagnosis could occur in conditions of low sensitivity following the surveillance capacity of each country; (iii) indicators of domestic infestation (disaggregated in intra and peridomicile) by the main triatomine specie, as a vector implicated in active transmission of disease at the geographic area under consideration; given that its low quantification would prove the low possibilities of transmission. This indicator would be used alongside other entomological indicators that provide further information specific to each case being evaluated. The following would be used as base indicators: infestation index equal to or less than 1% disaggregated into intradomicile infestation index and peridomicile infestation index. In the case of autochthonous vectors the peridomicile infestation index can be up to 5%.

The concept of “interruption of the vector transmission of T. cruzi ” according to Abad-Franch et al. (2013) , has been useful and effective for the control of vectors introduced (not native) in: Uruguay (1997), Chile (1999), Brazil (2006), Oriental Region of Paraguay (2008), several provinces or department of Argentina (2001, 2004, 2011, 2012), two departments of Peru (Tacna 2009, Moquegua 2010), two states in the south of Mexico (Chiapas and Oaxaca 2009), Guatemala (2008), Honduras (2010), Nicaragua (2010), El Salvador (2010) and Costa Rica (2011). The same authors, however, consider that the utilization of the same concept would not have similar outcome in areas where the transmission depends on species that are native, using as examples the department of La Paz (Bolivia), “some localities in Chaco, Argentina” and non-Amazonian endemic areas of Brazil.

It is important to emphasise that all the certification processes follow a protocol clearly described ( OPS 2002 , 2010 ) that contemplate, among others, the participation of international and national experts of the country and the region where the interruption verification work is carried out. Important criteria also used are based on information provided by the country, revision of alternative reports and studies available by other bibliographical sources and information from the national epidemiological system of the implicated country.

In the case of the examples cited previously (La Paz, Chaco from Argentine and non-Amazonian areas of Brazil), the following must be considered: the department of La Paz, Bolivia, received its certification in 2011 based primarily on a random sample of 5,301 children between zero-five years of age, taken from 330 communities of 21 endemic municipalities of La Paz, where only 45 (0.8%) pre-school children were positive and whose mothers were also positive. All of this was demonstrated through serologic studies using rapid tests, ELISA and reconfirming positive cases and randomly selected negatives samples. These results came from the same area where in 1990 the prevalence was 15.6% for the same study groups. In 2011, the index value for domestic infestation by T. infestans in La Paz was 1.3% with a clear predominance of peridomicile ( SEDES/La Paz 2010 , MSDB 2011 ). Within the four years previous to 2011 there are no reports of acute Chagas cases diagnosed in the department of La Paz ( OPS 2011 ).

Described as “some localities in Chaco, Argentina,” the departments of Aguirre, Mitre, Belgrano, Rivadavia, Ojos de Agua and Quebrachos in the south of the province of Santiago del Estero were evaluated between the years 2012-2013. A significant drop of intradomestic infestation by T. infestans was confirmed, with values between 0.26-1%. This reduction was assumed to be the result of vector control and the environmental transformations of development ( MSDSSE 2012 , 2013 ). These results came from the use of large percentages of the total population of children in each community, represented by pre-school age population, more specifically, zero-five years of age [194 children from Aguirre (24% of the total 0-5 age group population), 108 children from Mitre (47%), 83 children from Belgrano (18%), 125 children from Rivadavia (23%), 752 children from Ojos de Agua (47%) and 670 children from Quebrachos (50%)]. The prevalence value was of 0%, using serology based on techniques from Serokit and ELISA. The previous outcome is in contrast to the results found in studies performed in the same communities and population groups, where between 1994-1996 the prevalence in the group of children between zero-five years was of 5.8% in Aguirre, 2.4% in Mitre, 6% in Ojo de Agua and 3.4% in Quebrachos (MSDSSE 2012, 2013). Additionally, between 2012-2013, other studies were performed using subject groups from school age children (ages 5-15) via questionnaires that included from 80-99% of the total children population of that range [1,133 children from Aguirre (98%), 258 children from Mitre (99%), 1,487 children from Belgrano (98%), 720 children from Rivadavia (98%), 2,622 children from Ojo de Agua (80%) and 2,186 children from Quebrachos (86%)], resulting in detected prevalence values between 0.2-1%. These departments of Santiago del Estero have no recorded diagnosis of acute cases since 2000 ( MSN/SPPS 2011 ).

In the case of the endemic extra-Amazonian states of Brazil, where the infestation by T. infestans ( Silveira et al. 1984 ) never existed, as shown in the national seroepidemiologic survey of 2001-2008 ( Luquetti et al. 2011 ), it was demonstrated that the autochthonous vectors did not have any major impact on transmission within the domestic environment (based on a representative sample of children from 0-5 years of age): Ceará (2 positive cases in 9,797 samples), Rio Grande do Norte (1 case in 1,750), Alagoas (2 in 3,723), Sergipe (0 in 2,552) and Espírito Santo (0 in 1,885). This demostrates that in these territories, as well as in all extra-Amazonian areas, “there was a significant reduction in the rate of transmission of human Chagas disease in the country without any current recording of a continuous and/or sustained domestic transmission. The national seroprevalence survey (2001-2008) evidenced this situation for the whole endemic territory ( OPAS/OMS 2012 ). No acute Chagas cases have been registered in these states since 2008 ( MS 2012 ).

According to general literature, which are consistent with the technical guides utilised by PAHO/WHO, the term “elimination” is essentially a state of control (many times ideal) that requires permanent interventions in a community to be able to sustain such achievement. This is in contrast to eradication, which does not require further interventions after reaching the goal ( Dowdle 1998 , 1999 , Cochi & Dowdle 2011 , Hopkins 2013 ).

Without any doubt the “interruption of the vector transmission of T. cruzi ” by autochthonous (native) triatomines, is a goal adopted for control purposes. This is used because of its practicality and concrete methods of measuring the achievement and progress of work through time and because of the dynamic evolution of the factors that intervene in the transmission of this disease. This goal of elimination depends on an installed, sustainable and feasible surveillance that adapts to the necessities of each epidemiological scenario for its periodic registration. Such surveillance system should guide the programs of control of the disease in the decision-making process over which actions need to be taken next, including the necessary adjustments that need to be made so that such actions are effective. All this keeping in mind possible distracting elements such as, the adaptation or substitution of the transmission vectors, modifications in the population dynamics or, eventually, the resistance to insecticides. This does not ignore the fact that in a zoonosis with a natural sylvatic cycle, the occurrence of isolated cases, sporadic or accidental, of human Chagas, or the documented existence of likely scenarios to the recurring peri or intradomiciliary colonisation of some species of vectors, that until now have not demonstrated significant evidence of public health importance, should not be considered in the existing epidemiological surveillance routine.

Even in more important species such as T. infestans, situations exist, such as that in Chile, a country with a recognised status of “interruption of the vector transmission of T. cruzi ” since 1999 ( WHO 1999 , Lorca et al. 2001 ), that do register the presence of this specie in wild habitats of Regions V, IV and Metropolitan ( Bacigalupo et al. 2010 ).

PAHO/WHO has been consistent with the countries of the Americas, promoting and supporting a technical cooperation that is effective an evidence-based. All this is done for the development of a strengthened surveillance (in quality, sensibility and coverage), strategically integrated to the national epidemiological surveillance and methodologically feasible. This includes the better use of diagnostic laboratory tests most ideal to each country and region. Because of this, such cooperation is fundamental in order to progress toward the prevention of new cases and the control of Chagas. Nevertheless, the final decision of the countries to confront the challenge and give priority to this health topic and regional pathology, must offer clear and feasible goals of public health impact, similar to those that invigorated throughout 23 years the existence of the Subregional Initiatives, making them successful.

It is probable that the general transformations of Public Health in the Region during the last three decades had influenced negatively the public health policy decisions made as well as the assignment of resources, recognising Chagas disease as a problem only at the bottom of priorities. This does not necessarily might be linked to the responsibility of the “punishment of success”, that is, to greater control fewer resources. The Americas have been traditionally a leader in these processes of Public Health in other fields, such as immunopreventable diseases and neglected infectious diseases. More importantly, these countries have continue responding responsibly to the challenges of maintaining such reached goals.

There is still a lot to be done and a proposal of evaluation of “good practices” in the prevention, control of Chagas disease, as a complimentary evaluating mechanism of “process”, is supported by PAHO/WHO. Such proposal could help improve the conceptual framework and fieldwork that must be perfected and democratised in the space of the Subregional Initiatives. Nonetheless, it is clear that such proposal does not constitute as an alternative to the impact evaluation of work developed by the countries that are struggling to reach the “interruption of the vector transmission;” which as of now it continues to be transitional and modifiable and yet, the best available option to measure the progress made in a Public Health scale (“the art of the possible”).

Acknowledgments

PAHO would like to acknowledge all health workers of all times, whom day by day, add their silent and constructive effort on the field and home by home, under the most difficult geographical conditions and circumstances, to protect their communities from the vector transmission of Chagas disease.

REFERENCES

- Abad-Franch F, Diotaiuti L, Gurgel-Gonçalves R, Gürtler RE. Certifying the interruption of Chagas disease transmission by native vectors: cui bono ? Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2013;108:251–254. doi: 10.1590/0074-0276108022013022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacigalupo A, Torres-Pérez F, Segovia V, García A, Correa JP, Moreno L, Arroyo P, Cattan PE. Sylvatic foci of the Chagas disease vector Triatoma infestans in Chile: description of a new focus and challenges for control programs. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2010;105:633–641. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762010000500006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochi SL, Dowdle WR. Strungmann forum report. Vol. 7. MA MIT Press; Cambridge: 2011. Disease eradication in the 21st century: implications for global health.311 [Google Scholar]

- Dowdle WR. The principles of disease elimination and eradication. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76(2):S22–S25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdle WR. The principles of disease elimination and eradication. MMWR. 1999;48(1):S23–S27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins D. Disease eradication. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:54–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1200391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INCOSUR - Iniciativa Intergubernamental de Salud de los Países del Cono Sur Resolución sobre Control de Enfermedades Zoonóticas (04-3-CS) PAHO; Brasilia: 1991. 85 [Google Scholar]

- Lorca M, García A, Bahamonde MI, Fritz A, Tassara R. Certificación serológica de la interrupción de la transmisión vectorial de la enfermedad de Chagas en Chile. Rev Med Chil. 2001;129:266–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luquetti A, Passos AC, Silveira AC, Ferreira A, Macedo V, Prata A. O inquérito nacional de prevalência de avaliação do controle da doença de Chagas no Brasil (2001-2008) Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2011;44(2):S108–S121. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822011000800015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MS - Ministerio da Saúde Doença de Chagas. Aspectos epidemiológicos. 2012 portal.saude.gov.br/portal/saude/profissional/visualizar_texto.cfm?idtxt=31454

- MSDB - Ministerio de Salud y Deportes de Bolivia Informe situacional. Prevención, control e impacto hacia la certificación de la interrupción de la transmisión vectorial de Trypanosoma cruzi por Triatoma infestans en 23 municipios endémicos del departamento de La Paz. MSDB; La Paz: 2011. 23 [Google Scholar]

- MSDSSE - Ministerio de Salud y Desarrollo Social de Santiago del Estero Documento técnico. Interrupción de la transmisión vectorial de T. cruzi en los departamentos de Aguirre, Belgrano, Mitre y Rivadavia. MSDSSE; Santiago del Estero: 2012. 50 [Google Scholar]

- MSDSSE - Ministerio de Salud y Desarrollo Social de Santiago del Estero Documento técnico. Interrupción de la transmisión vectorial de T. cruzi en los departamentos de Ojo de Agua y Quebrachos. MSDSSE; Santiago del Estero: 2013. 76 [Google Scholar]

- MSN/SPPS - Ministerio de Salud de la Nación/Secretaría de Promoción y Programas Sanitarios Boletín Integrado de Vigilancia 93 SE 40. MSN; Buenos Aires: 2011. 69 [Google Scholar]

- OPAS/OMS - Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde/Organização Mundial da Saúde Oficina para discussão da proposta de “certificação da interrupção da transmissão da doença de Chagas por vetores secundários no Brasil’’, June 5-6 2012. OPAS/OMS; Brasilia: 2012. 3 [Google Scholar]

- OPS - Organización Panamericana de Salud Primera Reunión de la Comisión Intergubernamental de la Iniciativa de Centroamérica y Belice para la Interrupción de la Transmisión Vectorial de la Enfermedad de Chagas por Rhodnius prolixus , disminución de la infestación domiciliaria por Triatoma dimidiata y Eliminación de la Transmisión Transfusional del Trypanosoma cruzi , OPS/HCP/HCT/145/99. Guatemala: 1998. 18 [Google Scholar]

- OPS - Organización Panamericana de Salud Guía de Evaluación de los procesos de control de triatomineos y del control de la transmisión transfusional de T. cruzi , OPS/HCP/HCT/196.02. OPS; Washington: 2002. 8 [Google Scholar]

- OPS - Organización Panamericana de Salud Comisión Intergubernamental de la Iniciativa Andina de Control de la Transmisión Vectorial y Transfusional de la Enfermedad de Chagas , OPS/HCP/HCT/223/04. OPS; Lima: 2004. 35 [Google Scholar]

- OPS - Organización Panamericana de Salud Marco referencial de los procesos hacia la interrupción de la transmisión vectorial de T. cruzi . Guía de definiciones. OPS; Montevideo: 2010. 2 [Google Scholar]

- OPS - Organización Panamericana de Salud XVIIIa Reunión de la Comisión Intergubernamental de la Iniciativa Subregional Cono Sur de Eliminación de Triatoma infestans y la Interrupción de la Transmisión Transfusional de la Tripanosomiasis Americana, Cochabamba, Bolivia, 2011 Julio 27-29, Document HSD/CD/008-11. Organización Panamericana de la Salud; Montevideo: 2011. 69 [Google Scholar]

- SEDES/La Paz Boletín Informativo Epidemiológico SEDES. Vol. 4. La Paz: 2010. La enfermedad de Chagas “una tragedia silenciosa”; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Silveira AC, Feitosa VR, Borges R. Distribuição de triatomíneos domiciliados no período 1975/1983 no Brasil. Rev Bras Malariol D Trop. 1984;36:15–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO - World Health Organization Chagas disease, interruption of transmission in Uruguay. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 1998;2:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- WHO - World Health Organization Chagas disease, interruption of transmission in Chile. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 1999;2:9–11. [Google Scholar]