Abstract

NK-2, a membrane-acting antimicrobial peptide, was derived from the cationic core region of porcine NK-lysin and consists of 27 amino acid residues. It adopts an amphipathic, α-helical secondary structure and has been shown to interact specifically with membranes of negatively charged lipids. We therefore investigated the interaction of NK-2 with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the main, highly anionic component of the outer leaflet of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria, by means of biophysical and biological assays. As model organisms and a source of LPS, we used Salmonella enterica strains with various lengths of the LPS carbohydrate moiety, including smooth LPS, rough LPS, and deep rough LPS (LPS Re) mutant strains. NK-2 binds to LPS Re with a high affinity and induces a change in the endotoxin-lipid A aggregate structure from a cubic or unilamellar structure to a multilamellar one. This structural change, in concert with a significant overcompensation of the negative charges of LPS, is thought to result in the neutralization of the endotoxic LPS activity in a cell culture system. Neutralization of LPS activity by NK-2 as well as its antibacterial activity against the various Salmonella strains strongly depends on the length of the sugar chains of LPS, with LPS Re being the most sensitive. This suggests that a hydrophobic peptide-LPS interaction is necessary for efficient neutralization of the biological activity of LPS and that the long carbohydrate chains, besides their function as a barrier for hydrophobic drugs, also serve as a trap for polycationic substances.

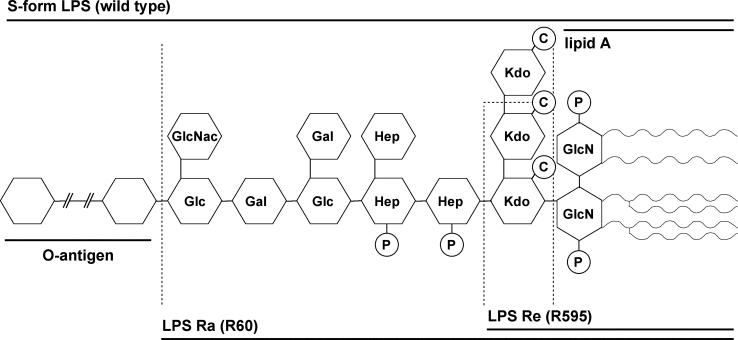

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), also termed endotoxin, the major constituent of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria, may be released from bacteria into the bloodstream during infection and then act as a potent activator of human mononuclear cells and macrophages (35). This activation first leads to local inflammation, which may be beneficial to the host. If the amount of LPS released, however, exceeds a certain threshold, the strong induction of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukins and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) results in severe sepsis and septic shock with organ dysfunction, which is responsible for the 30 to 40% death rate among patients with sepsis (4), as no specific effective treatment is available. The glycolipid LPS consists of the bioactive lipid A moiety, termed the “endotoxic principle” of LPS, with a d-glucosamine backbone replaced by 3-hydroxy fatty acids, which anchors the molecule in the outer leaflet of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria, and a covalently linked carbohydrate chain of various lengths (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic structures of S. enterica LPSs used in this study. The molecular masses of lipid A, LPS Re, LPS Ra, and S-form LPS are 2.3, 2.65, 4.3, and 10 kDa, respectively. GlcNac, N-acetyl-d-glucosamine; Glc, d-glucose; Gal, d-galactose; Hep, l-glycero-d-manno-heptose; Kdo, 3-deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulopyranosonic acid; GlcN, d-glucosamine; P, phosphate; C, carboxylate.

After the release of LPS from the bacterial membrane due to cell division, cell death, or, in particular, treatment of the bacterial infection with antibiotics (34), activation of the host cells is mediated through specific interactions with serum proteins or cell surface receptors, such as the LPS-binding protein (LBP) and CD14 (21, 25, 26, 40). Further downstream, toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) (20) in complex with MD2 (39) or a stress-sensitive potassium channel (6) is involved in the signaling process and leads to the release of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α. Present antisepsis strategies use anti-LPS or anti-TNF-α antibodies to bind and neutralize LPS or to capture the released TNF-α, respectively; however, these strategies have had limited success (22). An alternative strategy relies on the fact that naturally occurring positively charged proteins that interact with LPS, such as lactoferrin (14, 19), CAP18 (31), NK-lysin (1), or shortened peptides derived from those molecules (5, 44), are capable of inhibiting the LPS-induced production of inflammatory cytokines by macrophages.

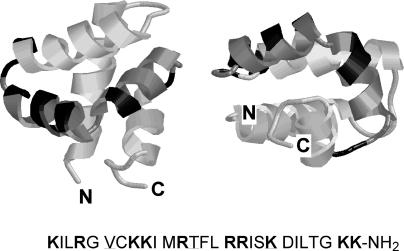

We have developed a potent peptide antibiotic, termed NK-2 (3, 37), which is a 27-amino-acid-residue derivative of the cationic core region of NK-lysin (Fig. 2), a cytolytic and antimicrobial polypeptide of mammalian lymphocytes (2) and a member of the membrane-interacting, saposin-like protein family with a common α-helical fold and a conserved half-cysteine pattern (33). The peptide NK-2 is very potent against bacteria and fungi (3) and also against the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi (28), but it has low levels of toxicity for human cells (3, 28). The molecular size, charge, and amphipathic α-helical structure of NK-2 place it together with an increasing number of natural antimicrobial peptides that are part of the innate immune systems of a variety of species, ranging from insects to humans (for reviews, see references 7 and 43). These peptides kill microorganisms by disturbing or destroying the barrier function of their membranes. Although they do not act by a general mechanism, it is accepted that negatively charged membranes rather than any specific receptor are their main targets (27, 41). This has been proven in particular for the peptide NK-2 (37) and also for its parental peptide, NK-lysin (18, 36). As a usually highly negatively charged component of the outer leaflet of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria, LPS is thus the first target of these cationic peptides in vivo.

FIG. 2.

Primary structure of the NK-2 peptide and tertiary structure of its parental protein, NK-lysin (in two different views). The nuclear magnetic resonance imaging structure of NK-lysin (32) was taken from the protein data bank (1NKL.pdb) and was displayed by use of the Rasmol program. NK-2 spans the third and the fourth helical domains (in gray) of NK-lysin, including the (mostly positively charged) adjacent amino acid residues. Lysine and arginine residues within the NK-2 structure are darkened. Note that the sequence of NK-2 differs from that of NK-lysin by the exchange of the underlined amino acid residues (37).

In this context we investigated the interaction of NK-2 with LPS by various biophysical methods including Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectroscopy, small-angle X-ray scattering, and calorimetry. The observed data were complemented by data from in vitro assays that provided information about the dependence of the antibacterial activity of NK-2 on the LPS structure and the capability of NK-2 to inhibit the LPS-induced cytokine production of human immune cells. The results suggest a molecular model of the peptide-LPS interaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Peptide synthesis.

Peptide NK-2 was synthesized with an amidated C terminus by the solid-phase peptide synthesis technique on an automatic peptide synthesizer (model 433 A; Applied Biosystems) on standard 9-fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl (Fmoc)-amide resin according to the fastmoc synthesis protocol of the manufacturer. The N-terminal Fmoc group was removed from the peptide resin, and the peptide was deprotected and cleaved with 90% trifluoroacetic acid, 5% anisole, 2% thioanisole, and 3% dithiothreitol for 3 h at room temperature. After cleavage, the suspension was filtrated and the soluble peptides were precipitated with ice-cold diethyl ether, followed by centrifugation and extensive washing with ether. The peptides were purified by reversed phase high-performance liquid chromatography with an Aqua-C18 column (Phenomenex, Aschaffenburg, Germany). Elution was done with a gradient of 0 to 70% acetonitrile in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. Mass spectrometric (matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight [MALDI-TOF] mass spectrometry; Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) analysis of the purified peptide showed that the molecular mass of the peptide matched the calculated molecular mass of 3,202 Da.

Bacterial strains.

The bacterial strains used in the study were wild-type or LPS mutant strains of Salmonella enterica (serovar Minnesota) with smooth-form LPS (S form; wild type), strain R60 with rough LPS (LPS Ra), and strain R595 deep rough LPS (LPS Re). The bacteria were grown overnight in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium, composed of 1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 1% NaCl, under constant shaking at 37°C and were subsequently inoculated in the same medium to reach the mid-logarithmic phase.

Lipids and reagents.

LPSs were extracted from various strains of S. enterica (serovar Minnesota), which had been grown at 37°C, purified, and lyophilized, by phenol-water treatment for S-form LPS (42) or by the phenol-chloroform-petrol ether method (24) for LPS Ra. Free lipid A was isolated from the LPS Re mutant (strain R595) by acetate buffer treatment. After isolation, the resulting lipid A was purified and converted to its triethylamine salt. The known chemical structure of lipid A from the strain R595 LPS was checked by analysis of the amounts of glucosamine and total and organic phosphates and the distribution of the fatty acid residues by standard procedures. The amount of 2-keto-3-deoxyoctonate never exceeded 5% (wt/wt). LBP, a kind gift from S. F. Carroll (XOMA Corporation, Berkeley, Calif.), was stored at −70°C as a 1-mg/ml stock solution in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5)-150 mM NaCl-0.002% (vol/vol) Tween 80-0.1% F68.

Preparation of endotoxin aggregates.

LPS or lipid A was solubilized in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.0) by vortexing, sonicated in a water bath at 60°C for 30 min, cooled to room temperature, and subjected to three or four cycles of heating to 60°C and cooling to room temperature. After that procedure, the lipid samples were stored for at least 12 h at 4°C before use.

Assay for antibacterial activity.

The peptide was dissolved at a concentration of 50 μg/ml in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), and 180 μl of this solution was placed in the first well of a microtiter plate. For twofold serial dilution, 90 μl from each well was transferred to the next well, which was then filled with the same volume of buffer. Subsequently, a suspension of log-phase bacteria in LB medium (10 μl, containing 104 CFU) was added to the peptide solution (90 μl). The plates were incubated overnight in a wet chamber at 37°C with constant shaking, and bacterial growth was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 620 nm in a microtiter plate reader (Rainbow; Tecan, Crailsham, Germany). The MIC was defined as the lowest peptide concentration at which no bacterial growth was measurable. Portions of each well (10 μl) were diluted with 90 μl of HEPES buffer, plated out in duplicate on LB agar plates, and incubated overnight at 37°C; and the bacterial colonies were counted. The minimal bactericidal concentration was defined as the peptide concentration at which no colony growth was observed.

Zeta potential.

Zeta potentials were determined from the electrophoretic mobility by laser Doppler anemometry with a Zeta-Sizer 4 instrument (Malvern Instruments, Herrsching, Germany) at a scattering angle of 90°, as described earlier (14). The zeta potential was calculated by the Helmholtz-Smoluchovski equation from the mobility of the aggregates in a driving electric field of 19.2 V/cm. Endotoxin aggregates (0.1 mM) and NK-2 stock solutions (0.5 mM) were prepared in 10 mM Tris-2 mM CsCl (pH 7.0).

Isothermal titration calorimetry.

Microcalorimetric experiments of peptide binding to LPS were performed on an MSC isothermal titration calorimeter (Microcal Inc., Northhampton, Mass.) at 40°C, as described previously (11). Briefly, after thorough degassing of the samples, peptide (1 to 4 mM in 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.0]) was titrated to an LPS suspension (0.05 mM in 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.0]). The enthalpy change during each injection was measured by the instrument, and the area under each injection peak was integrated (Origin; Microcal) and plotted against the peptide molar concentration:LPS molar concentration ratio (peptide:LPS molar ratio). Titration of the pure peptide into HEPES buffer resulted in a negligible endothermic reaction due to dilution, and the absorbed heat was subtracted from the plotted curves. The experiments were done at least twice.

FTIR spectroscopy.

The infrared spectroscopic measurements were performed on an IFS-55 spectrometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany). Samples were dissolved in 20 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.0) and were placed in a CaF2 cuvette with a 12.5-μm Teflon spacer. Temperature scans were performed automatically between 10 and 70°C with a heating rate of 0.6°C/min. At every 3°C, 50 interferograms were accumulated, apodized, Fourier transformed, and converted to absorbance spectra. For strong absorption bands, the band parameters (peak position, bandwidth, and intensity) were evaluated from the original spectra, if necessary, after subtraction of the strong water bands.

X-ray diffraction.

X-ray diffraction measurements were made at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory outstation at the Deutsches Elektronen Synchrotron (Hamburg, Germany) with the X33 double-focusing monochromator-mirror camera (30). Diffraction patterns in the range of scattering vector 0.07 < s < 1 nm−1 (where s is 2 sin θ/λ, 2θ is the scattering angle, and λ is the wavelength, which was 0.15 nm) were recorded from the lipid samples (5 mg/ml) at the indicated temperatures with exposure times of 2 or 3 min by using a linear detector with a delay line readout (23). The s axis was calibrated with tripalmitin, which has a periodicity of 4.06 nm at room temperature. Details of the data acquisition and evaluation system can be found elsewhere (9). The diffraction patterns were evaluated as described previously (12) by assigning the spacing ratios of the main scattering maxima to defined three-dimensional structures. The lamellar and cubic structures are most relevant here. They are characterized by the following features: (i) for the lamellar structure, the reflections are grouped in equidistant ratios, i.e., 1, 1/2, 1/3, 1/4, etc., of the lamellar repeat distance, dL; (ii) for the cubic structure, the different space groups of these nonlamellar three-dimensional structures differ in the ratios of their spacings. The relation between reciprocal spacing shkl = 1/dhkl and lattice constant a is shkl = [(h2 + k2 + l2)/a]1/2 (where h, k, and l are Miller indices of the corresponding set of planes).

Competitive ELISA.

LPS Re (50 μl, 5 μg/ml in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS; 140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 8 mM Na2HPO4, 2.4 mM KH2PO4 {pH 7.2}]) was coated on flexible 96-well enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates (U-form; Falcon) overnight at 4°C with constant shaking. The liquid was removed; and the plates were washed extensively with PBS, blocked by incubation with 10% milk powder (low fat) for 1 h at 37°C, washed once more with PBS, and incubated with a twofold serial dilution of LBP (100 μl) or with NK-2 and LBP mixtures (molar ratios, 3:1 to 100:1) in PBS (10 μg/ml) overnight at 4°C with constant shaking. The liquid was removed; and the plates were washed extensively with PBS, incubated with a monoclonal anti-LBP antibody (biG42; 1:5,000 in 5% milk powder-PBS; Biometec, Greifswald, Germany) for 1 h at 37°C, washed again, incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody against mouse immunoglobulin G (1:10,000 in 5% milk powder-PBS; Sigma) for 1 h at 37°C, washed again, and developed with tetramethylbenzidine-H2O2. The emerging color reaction was stopped by the addition of sulfuric acid, and the plates were analyzed in a microtiter plate reader (Rainbow; Tecan) at 450 nm. The data from three independent experiments, each performed in duplicate, were averaged. Percent inhibition of LBP binding to LPS was calculated as [(Ic − I0)/(Iexp − I0)] × 100 (where Iexp is the ELISA signal of the various NK-2-LBP mixtures, Ic is the signal for the respective concentration of LBP, and I0 is the LPS background signal) and was plotted against the NK-2:LBP molar ratios (data not shown). The NK-2 molar excess necessary to inhibit the binding of LBP to LPS by 50% was calculated from this curve.

Preparation of MNCs and macrophages.

Mononuclear cells (MNCs) were isolated from heparinized blood of healthy donors as described previously (13). For the proliferation to macrophages, the cells (approximately 4 × 106/ml) were kept in medium (RPMI 1640, 4% human serum) supplemented with macrophage colony-stimulating factor (2 ng/ml; R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany) and incubated in Teflon bags for 7 days at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Stimulation of human MNCs by LPS.

The cells were resuspended in medium (RPMI 1640, 4% human serum), and the cell number was equilibrated to 5 × 106 cells/ml. For stimulation, 200 μl of MNCs (106 cells) or macrophages (105 cells) was transferred into each well of a 96-well culture plate. LPS and peptide-LPS mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 37°C and added to the cultures at 20 μl per well (final concentrations, 1 ng/ml for LPS Re, 0.5 ng/ml for LPS Ra, and 1 ng/ml for S-form LPS). The cultures were incubated for 4 h at 37°C under 5% CO2. The supernatants were collected after centrifugation of the culture plates for 10 min at 400 × g, stored overnight at 4°C, and used for the immunological determination of TNF-α by a sandwich ELISA with a monoclonal antibody against TNF-α (clone 6b; Intex AG, Muttent, Switzerland), as previously described in detail (29).

RESULTS

Antibacterial activity of NK-2 depends on bacterial LPS structure.

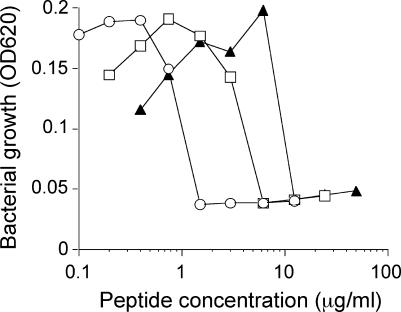

The influence of the LPS carbohydrate structure on the antibacterial activity of the NK-2 peptide was investigated by measuring the efficiency of NK-2 inhibition of growth of the Salmonella strains, which differed only with respect to their LPS sugar structures. The bacterial strains used were (i) wild-type S. enterica with S-form LPS, which contains a full O-antigenic carbohydrate chain; (ii) mutant strain R60 with LPS Ra, which contains the complete core sugars; and (iii) mutant strain R595 with LPS Re, which lacks the O-antigenic chain and has, besides lipid A, only the 2-keto-3-deoxyoctonate monosaccharides (Fig. 1). The inhibitory concentrations of NK-2 for bacterial suspensions (Fig. 3) as well as the bactericidal concentrations of the peptide for the bacterial colonies after the suspensions were plated out were determined. The sensitivities of the different Salmonella strains to treatment with NK-2 were R595 > R60 > wild type, which indicates a clear correlation between the activity of the peptide and the length of the LPS carbohydrate moiety. The concentration of NK-2 necessary to kill the bacteria in general was higher (1 dilution step in the twofold serial dilution) than the growth-inhibiting concentration shown in Fig. 3. Apparently, bacterial growth is stimulated at peptide concentrations below the MIC or the minimal bactericidal concentration. This is a reproducible, albeit difficult to quantitate, phenomenon which has also been observed for other antimicrobial peptides.

FIG. 3.

Activity of NK-2 against S. enterica strains with various LPS carbohydrate structures: strain R595 (LPS Re; circles), strain R60 (LPS Ra; squares), and wild type (S-form LPS; triangles). The data shown were taken from a representative experiment. Inhibitory concentrations obtained from two independent experiments, each performed in duplicate, were exactly within 1 dilution step. OD620, optical density at 620 nm.

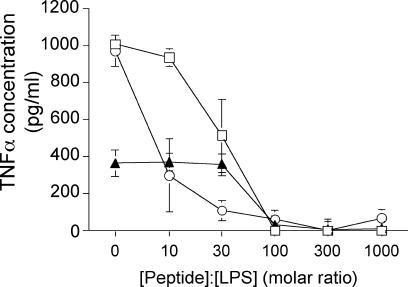

TNF-α induction in human MNCs.

TNF-α is one of the major cytokines that is biosynthesized and secreted by human MNCs and macrophages upon stimulation by LPS. Inhibition of LPS-induced TNF-α production by NK-2 was monitored by ELISA. Preincubation of the three different types of LPSs (the S-form, Ra, and Re LPSs) with NK-2 resulted in a dose-dependent reduction in the level of TNF-α production by the cells (Fig. 4). More than 50% inhibition of TNF-α secretion was observed at 10-, 30-, and 100-fold molar excesses of NK-2 over Re, Ra, and S-form LPSs, respectively. As in the case of bacterial growth (Fig. 3), for compounds with longer sugar chains, more peptide was needed for expression of a significant reduction of TNF-α inhibition.

FIG. 4.

Concentration-dependent inhibition of the biological activities of various LPSs by NK-2. LPS Re (circles), LPS Ra (squares), and S-form LPS (triangles) were incubated with NK-2 at the indicated peptide:LPS molar ratios and were used to activate human MNCs. As a marker of LPS-induced cell activation, the level of production of the cytokine TNF-α was determined by ELISA. Similar results were observed when macrophages instead of MNCs were used (data not shown).

NK-2 binding affinity to LPS.

The affinity of NK-2 for LPS Re in terms of LPS-LBP binding affinity was estimated by competitive ELISA. NK-2 and LBP were preincubated together and placed into LPS-coated microtiter plates. The amount of LPS-bound LBP was then determined by using a specific anti-LBP antibody. Fifty percent inhibition of LBP binding to LPS was observed with an approximately 10-fold molar excess of NK-2 to LBP, which corresponds to a NK-2 mass:LBP mass ratio of 1:1.5, indicating that NK-2 has a very high affinity of binding to LPS.

Influence of NK-2 on supramolecular aggregate structure of lipid A.

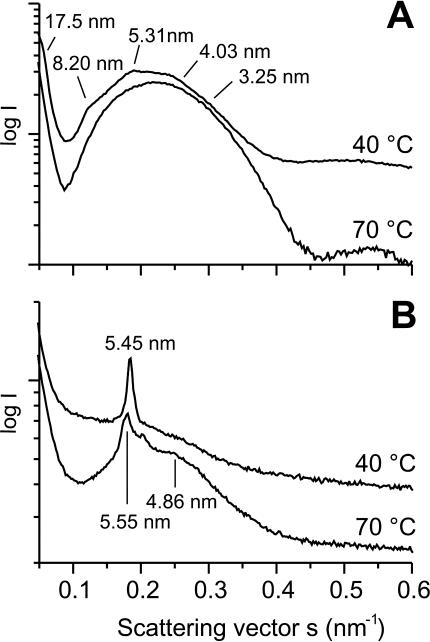

The three-dimensional aggregate structure of endotoxin (lipid A) in the presence and absence of NK-2 was analyzed by small-angle X-ray scattering. The diffraction pattern of pure lipid A is indicative of a unilamellar structure superimposed on a nonlamellar, probably cubic structure (Fig. 5A). Due to the limited numbers and the limited resolutions of the reflections, no clear assignment to a particular cubic space group is possible. Addition of NK-2 converts the cubic structure into a multilamellar structure with a periodicity of 5.45 nm at an endotoxin:peptide molar ratio of 1:0.01 (Fig. 5B). At higher temperatures (70°C) this multilamellar structure is superimposed on an inverted hexagonal (HII) structure, as evidenced by the reflection at 4.86 nm (Fig. 5B). Binding of NK-2 to lipid A at 40°C thus leads to a conversion of the molecular shape of the endotoxin from a conical to a cylindrical one.

FIG. 5.

Influence of NK-2 on the supramolecular structure of lipid A aggregates. Small-angle X-ray diffraction patterns were determined for pure lipid A (A) and a lipid A-NK-2 mixture (molar ratio, 1 to 0.01) (B) at the indicated temperatures.

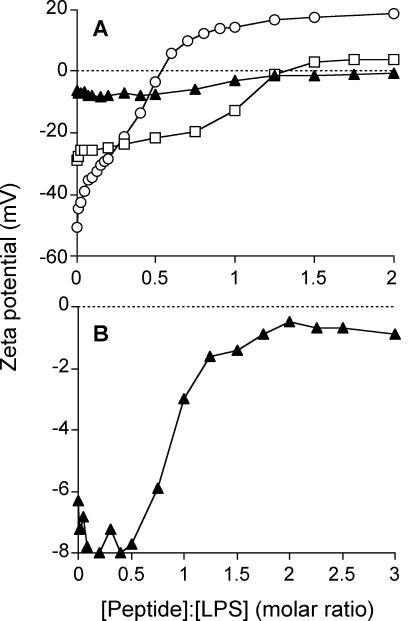

Surface charge compensation of LPS aggregates by NK-2.

Binding of the cationic peptide NK-2 to LPS results in a compensation of the negative surface charge of LPS, as monitored by measuring the zeta potentials of the LPS aggregates (Fig. 6). Whereas neutralization of the surface charge was observed for the S-form LPS and mutant LPS Ra, addition of NK-2 to mutant LPS Re even resulted in a positive zeta potential above a peptide:LPS molar ratio of about 0.5 (overcompensation).

FIG. 6.

Zeta potentials of LPS preparations (circles, LPS Re; squares, LPS Ra; triangles, S-form LPS) on the basis of different NK-2:LPS molar ratios. Zeta potentials were determined from electrophoretic mobilities by laser Doppler anemometry (A). For clarity, the zeta potential of S-form LPS is shown on an expanded scale (B).

Influence of NK-2 on gel-to-liquid crystalline phase-transition behavior of LPS.

The gel-to-liquid crystalline (β-to-α) acyl chain melting behavior of mutant LPS Re was investigated by FTIR by evaluating the peak position of the symmetric stretching vibration, vs(CH2), which is a measure of the acyl chain order (data not shown). NK-2 has a stabilizing effect on the LPS aggregates, which induces a slight shift of the phase transition (chain melting temperature, 31.9°C for pure LPS) to higher temperatures (+1.7°C and +2.6°C at LPS:peptide molar ratios of 1: 0.03 and 1:0.1, respectively).

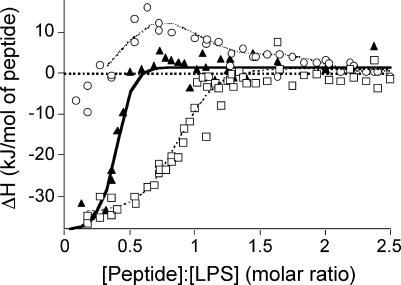

LPS-NK-2 binding enthalpy.

The enthalpy of the binding reaction of NK-2 to LPS was monitored by isothermal titration calorimetry, and marked differences in the enthalpies were found for the three different types of LPSs investigated (Fig. 7). Whereas the binding reaction of NK-2 to LPS Re was more or less endothermic, titration of NK-2 to LPS Ra and S-form LPS gave a strong exothermic reaction, with minor portions of endothermic behavior, suggesting an electrostatically driven interaction.

FIG. 7.

Enthalpy change (ΔH) of the peptide-LPS (circles, Re LPS; squares, Ra LPS; triangles, S-form LPS) binding reaction on the basis of various NK-2:LPS molar ratios. The enthalpy changes were determined from calorimetric titration curves. Positive and negative enthalpy change values indicate endothermic and exothermic reactions, respectively.

DISCUSSION

From previous work, there was evidence that the activity of the antimicrobial peptide NK-2 depends on the LPS structures of the target bacteria, as illustrated by the fact that the MIC of NK-2 for Escherichia coli K-12, which has LPS Ra, was four times higher than that of NK-2 for E. coli D31 (0.6 and 0.15 μM, respectively) (3), a K-12 mutant strain with a minimalized LPS core structure (8). In the present study, we proved a direct peptide-LPS interaction and investigated the relationship between the length of the LPS carbohydrate chain and the biological activity of NK-2, i.e., its antibacterial and LPS-neutralizing activities. For this we used as model organisms S. enterica strains with sugar chains of various lengths: strain R595 with Re LPS, strain R60 with Ra LPS, and a wild-type strain with S-form LPS. The biological data were supplemented by biophysical measurements of the accessible surface charges of the LPS aggregates, calorimetric titration of the peptides with various LPSs, and determination of the influence of the peptide on the LPS acyl chain melting behavior as well as on the endotoxin (lipid A) supramolecular aggregate structure.

NK-2 strongly interacts with LPS. Its affinity, as estimated by binding competition with LBP, is an order of magnitude lower than the LPS-LBP dissociation constant (6 × 10−9 M) (40). Interestingly, it is still an order of magnitude higher than the LPS-binding affinity of the NK-2 parental protein, NK-lysin, which has been determined to be approximately 0.7 × 10−6 M (1). As a consequence, preincubation of NK-2 with LPS and subsequent treatment of MNCs or macrophages leads to inhibition of LPS-induced TNF-α production in the immune cells at rather low peptide:LPS molar ratios. This relatively high affinity of NK-2 to LPS may allow the displacement of LBP and thus facilitate LPS neutralization activity in vivo as well. In fact, the parental protein, NK-lysin, was able to inhibit LPS activity in vivo, but only after preincubation with LPS. NK-lysin failed to exhibit the same activity when it was administered to mice after injection of LPS (1). This effect could be due to its much lower affinity to LPS compared to that of LBP or to the rapid internalization of LPS by immune cells and the subsequent activation of cell signaling. Although the dissociation constant of NK-2 to LPS Re is high, the effects on the phase-transition behaviors of the LPS acyl chains are only marginal. The effect of a shift to slightly higher temperatures, i.e., moderate rigidification, indicates that the peptide does not penetrate deeply into the hydrophobic core of the LPS aggregate, as observed, for example, for polymyxin B (17).

The cubic and unilamellar aggregate structure of endotoxin (lipid A) is converted into a multilamellar structure in the presence of the peptide, implying that the molecular shape of lipid A changed from a conical conformation (the hydrophobic moiety has a larger cross section than the hydrophilic one) to a cylindrical conformation, in which both cross sections are identical. This observation, together with the ability of NK-2 to inhibit LPS-induced TNF-α production by MNCs, is in accordance with the conformational concept of LPS activity (38). It was previously found that the conical shape of the lipid A part of the LPS molecule is necessary to exhibit endotoxic activity in a biological system (16, 38). This lamellarization of the endotoxin aggregates has also been observed for other proteins and polypeptides that inhibit the cell stimulation activity of LPS, such as lactoferrin (14), high-density lipoprotein (13), lysozyme (15), and polymyxin B (17). The interaction of LPS with LBP and CD14 may thus be directly influenced as a consequence of this structural change. Factors which are clearly affected by a change in the LPS-aggregate structure and which are considered to influence the bioactivity of LPS are (i) the binding energy within the LPS aggregate, which increases in the presence of the peptide; (ii) altered accessibility of LPS recognition sites, which are accessible for pure LPS but which are hidden in the multilamellar stacks; and (iii) the endotoxin aggregate structure itself (10; this study).

The interaction of NK-2 with mutant LPS Re is fundamentally different from that with mutant LPS Ra and S-form LPS. The sensitivity of bacteria to NK-2 treatment as well as the ability of the peptide to inhibit LPS-induced TNF-α production increased in parallel to a shortening of the LPS carbohydrate chains (i.e., LPS Re > LPS Ra > S-form LPS [Fig. 3 and 4]). Differences in the kinds of interactions can be deduced from the calorimetric and zeta potential measurements (Fig. 6 and 7). The NK-2 interaction with LPSs with longer carbohydrate chains (LPS Ra and S-form LPS) is mainly of an electrostatic nature; i.e., the binding of NK-2 is exothermic and takes place only until the negative surface charges of the LPS aggregates are fully compensated. In contrast, binding of NK-2 to LPS Re is mainly endothermic, with a significant charge overcompensation. Both facts indicate that, in contrast to the electrostatic interaction described above, a hydrophobic peptide-LPS interaction is the main driving force.

The goal of the present work was to demonstrate the ability of the antimicrobial peptide NK-2 to neutralize the immunostimulatory activity of LPS, i.e., to act as an antisepsis drug, and to characterize the peptide-LPS interaction at the molecular level by means of biophysical and biological assays. The interaction of the peptide with LPS is driven by electrostatic and hydrophobic forces. However, only the (albeit very superficial) hydrophobic penetration, which takes place with mutant LPS Re and which results in a strong charge overcompensation, is able to neutralize the biological activity of LPS efficiently. The long carbohydrate chains of LPS Ra and wild-type S-form LPS most likely serve as negatively charged, polar scavengers, which fits with the electrostatically driven NK-2-LPS binding reaction. This means that, besides their function as a barrier for hydrophobic antibiotics, they also weaken the effects of polycationic drugs against the bacteria. Our results indicate the necessity of a hydrophobic peptide-LPS interaction for efficient LPS neutralization activity; i.e., the peptide must pass the hydrophilic branches of the LPS carbohydrate chains. This takes place only after saturation of the carbohydrate chains with a cationic peptide has occurred and explains the need for a higher peptide concentration to neutralize LPS Ra and S-form LPS and also to kill the respective bacteria.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Lindner for obtaining the measurements by MALDI-TOF; and we are indebted to G. von Busse for technical assistance with infrared spectroscopy and K. Stephan for antibacterial testing and TNF-α determination, respectively.

This work was supported in part by the European Union (Project ANEPID).

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson, M., R. Girard, and P. Cazenave. 1999. Interaction of NK-lysin, a peptide produced by cytolytic lymphocytes, with endotoxin. Infect. Immun. 67:201-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson, M., H. Gunne, B. Agerberth, A. Boman, T. Bergman, R. Sillard, H. Jörnvall, V. Mutt, B. Olsson, H. Wigzell, A. Dagerlind, H. G. Boman, and G. H. Gudmundsson. 1995. NK-lysin, a novel effector peptide of cytotoxic T and NK cells. Structure and cDNA cloning of the porcine form, induction by interleukin 2, antibacterial and antitumour activity. EMBO J. 14:1615-1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrä, J., and M. Leippe. 1999. Candidacidal activity of shortened synthetic analogs of amoebapores and NK-lysin. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 188:117-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angus, D. C., W. T. Linde-Zwirble, J. Lidicker, G. Clermont, J. Carcillo, and M. R. Pinsky. 2001. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit. Care Med. 29:1303-1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blondelle, S. E., R. Jerala, M. Lamata, I. Moriyon, K. Brandenburg, J. Andrä, M. Porro, and K. Lohner. Structure-function studies of antimicrobial and endotoxin neutralizing peptides. In M. Chorev and T. K. Sawye (ed.), Peptide revolution: genomics, proteomics & therapeutics, in press. American Peptide Society, San Diego, Calif.

- 6.Blunck, R., O. Scheel, M. Müller, K. Brandenburg, U. Seitzer, and U. Seydel. 2001. New insights into endotoxin-induced activation of macrophages: involvement of a K+ channel in transmembrane signaling. J. Immunol. 166:1009-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boman, H. G. 1995. Peptide antibiotics and their role in innate immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 13:61-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boman, H. G., I. Nilsson-Faye, K. Paul, and J. T. Rasmuson. 1974. Insect immunity. I. Characteristics of an inducible cell-free antibacterial reaction in hemolymph of Samia cynthia pupae. Infect. Immun. 10:136-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boulin, C., R. Kempf, M. H. J. Koch, and S. M. McLaughlin. 1986. Data appraisal, evaluation and display for synchroton radiation experiments: hardware and software. Nucl. Instr. Methods 249:399-407. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brandenburg, K., J. Andrä, M. Müller, M. H. J. Koch, and P. Garidel. 2003. Physicochemical properties of bacterial glycopolymers. Carbohydr. Res. 338:2477-2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandenburg, K., M. D. Arraiza, G. Lehwark-Ivetot, I. Moriyon, and U. Zähringer. 2002. The interaction of rough and smooth form lipopolysaccharides with polymyxins as studied by titration calorimetry. Thermochim. Acta 394:53-61. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brandenburg, K., S. S. Funari, M. H. J. Koch, and U. Seydel. 1999. Investigation into the acyl chain packing of endotoxins and phospholipids under near physiological conditions by WAXS and FTIR spectroscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 128:175-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brandenburg, K., G. Jürgens, J. Andrä, B. Lindner, M. H. Koch, A. Blume, and P. Garidel. 2002. Biophysical characterization of the interaction of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) with endotoxins. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:5972-5981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandenburg, K., G. Jürgens, M. Müller, S. Fukuoka, and M. H. Koch. 2001. Biophysical characterization of lipopolysaccharide and lipid A inactivation by lactoferrin. Biol. Chem. 382:15-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandenburg, K., M. H. Koch, and U. Seydel. 1998. Biophysical characterization of lysozyme binding to LPS Re and lipid A. Eur. J. Biochem. 258:686-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandenburg, K., S. Kusumoto, and U. Seydel. 1997. Conformational studies of synthetic lipid A analogues and partial structures by infrared spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1329:183-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brandenburg, K., I. Moriyon, M. D. Arraiza, G. Lewark-Yvetot, M. H. J. Koch, and U. Seydel. 2002. Biophysical investigations into the interaction of lipopolysaccharide with polymyxins. Thermochim. Acta 382:189-198. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruhn, H., B. Riekens, O. Berninghausen, and M. Leippe. 2003. Amoebapores and NK-lysin, members of a class of structurally distinct antimicrobial and cytolytic peptides from protozoa and mammals—a comparative functional analysis. Biochem. J. 375:737-744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caccavo, D., N. Pellegrino, M. Altamura, A. Rigon, L. Amati, A. Amoroso, and E. Jirillo. 2002. Antimicrobial and immunoregulatory functions of lactoferrin and its potential therapeutic application. J. Endotoxin Res. 8:403-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chow, J. C., D. W. Young, D. T. Golenbock, W. J. Christ, and F. Gusovsky. 1999. Toll-like receptor-4 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 274:10689-10692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delude, R. L., R. Savedra, Jr., H. Zhao, R. Thieringer, S. Yamamoto, M. J. Fenton, and D. T. Golenbock. 1995. CD14 enhances cellular responses to endotoxin without imparting ligand-specific recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:9288-9292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher, C. J., Jr., S. M. Opal, J. F. Dhainaut, S. Stephens, J. L. Zimmerman, P. Nightingale, S. J. Harris, R. M. Schein, E. A. Panacek, J. L. Vincent, et al. 1993. Influence of an anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody on cytokine levels in patients with sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 21:318-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabriel, A. 1977. Position-sensitive X-ray detector. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 48:1303-1305. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galanos, C., O. Lüderitz, and O. Westphal. 1969. A new method for the extraction of R lipopolysaccharides. Eur. J. Biochem. 9:245-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gegner, J. A., R. J. Ulevitch, and P. S. Tobias. 1995. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) signal transduction and clearance dual roles for LPS binding protein and membrane CD14. J. Biol. Chem. 270:5320-5325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hailman, E., H. S. Lichenstein, M. M. Wurfel, D. S. Miller, D. A. Johnson, M. Kelley, L. A. Busse, M. M. Zukowski, and S. D. Wright. 1994. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein accelerates the binding of LPS to CD14. J. Exp. Med. 179:269-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hristova, K., M. E. Selsted, and S. H. White. 1997. Critical role of lipid composition in membrane permeabilization by rabbit neutrophil defensins. J. Biol. Chem. 272:24224-24233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobs, T., H. Bruhn, I. Gaworski, B. Fleischer, and M. Leippe. 2003. NK-lysin and its shortened analog NK-2 exhibit potent activities against Trypanosoma cruzi. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:607-613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jürgens, G., M. Müller, P. Garidel, M. H. Koch, H. Nakakubo, A. Blume, and K. Brandenburg. 2002. Investigation into the interaction of recombinant human serum albumin with Re-lipopolysaccharide and lipid A. J. Endotoxin Res. 8:115-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koch, M. H. J., and J. Bordas. 1983. X-ray diffraction and scattering on disordered systems using synchroton radiation. Nucl. Instr. Methods 208:461-469. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larrick, J., M. Hirata, R. Balint, J. Lee, J. Zhong, and S. Wright. 1995. Human CAP18: a novel antimicrobial lipopolysaccharide-binding protein. Infect. Immun. 63:1291-1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liepinsh, E., M. Andersson, J.-M. Ruysschaert, and G. Otting. 1997. Saposin fold revealed by the NMR structure of NK-lysin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4:793-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munford, R. S., P. O. Sheppard, and P. J. O'Hara. 1995. Saposin-like proteins (SAPLIP) carry out diverse functions on a common backbone structure. J. Lipid Res. 36:1653-1663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Periti, P., and T. Mazzei. 1998. Antibiotic-induced release of bacterial cell wall components in the pathogenesis of sepsis and septic shock: a review. J. Chemother. 10:427-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rietschel, E. T., H. Brade, O. Holst, L. Brade, S. Müller-Loennies, U. Mamat, U. Zähringer, F. Beckmann, U. Seydel, K. Brandenburg, A. J. Ulmer, T. Mattern, H. Heine, J. Schletter, H. Loppnow, U. Schonbeck, H. D. Flad, S. Hauschildt, U. F. Schade, F. Di Padova, S. Kusumoto, and R. R. Schumann. 1996. Bacterial endotoxin: chemical constitution, biological recognition, host response, and immunological detoxification. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 216:39-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruysschaert, J. M., E. Goormaghtigh, F. Homble, M. Andersson, E. Liepinsh, and G. Otting. 1998. Lipid membrane binding of NK-lysin. FEBS Lett. 425:341-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schröder-Borm, H., R. Willumeit, K. Brandenburg, and J. Andrä. 2003. Molecular basis for membrane selectivity of NK-2, a potent peptide antibiotic derived from NK-lysin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1612:164-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schromm, A. B., K. Brandenburg, H. Loppnow, A. P. Moran, M. H. J. Koch, E. T. Rietschel, and U. Seydel. 2000. Biological activities of lipopolysaccharides are determined by the shape of their lipid A portion. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:2008-2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimazu, R., S. Akashi, H. Ogata, Y. Nagai, K. Fukudome, K. Miyake, and M. Kimoto. 1999. MD-2, a molecule that confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness on Toll-like receptor 4. J. Exp. Med. 189:1777-1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tobias, P. S., K. Soldau, and R. J. Ulevitch. 1989. Identification of a lipid A binding site in the acute phase reactant lipopolysaccharide binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 264:10867-10871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, W., D. K. Smith, K. Moulding, and H. M. Chen. 1998. The dependence of membrane permeability by the antibacterial peptide cecropin B and its analogs, CB-1 and CB-3, on liposomes of different composition. J. Biol. Chem. 273:27438-27448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Westphal, O., O. Lüderitz, and F. Bister. 1952. Über die Extraktion von Bakterien mit Phenol/Wasser. Z. Naturforsch. 7:148. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zasloff, M. 2002. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 415:389-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang, G., D. Mann, and C. Tsai. 1999. Neutralization of endotoxin in vitro and in vivo by a human lactoferrin-derived peptide. Infect. Immun. 67:1353-1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]