Abstract

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) is a virulent pathogen that induces rapid host death. Here we observed that host survival after infection with S. Typhimurium was enhanced in the absence of type I interferon signaling, with improved survival of mice deficient in the receptor for type I interferons (Ifnar1−/− mice) that was attributed to macrophages. Although there was no impairment in cytokine expression or inflammasome activation in Ifnar1−/− macrophages, they were highly resistant to S. Typhimurium–induced cell death. Specific inhibition of the kinase RIP1or knockdown of the gene encoding the kinase RIP3 prevented the death of wild-type macrophages, which indicated that necroptosis was a mechanism of cell death. Finally, RIP3-deficient macrophages, which cannot undergo necroptosis, had similarly less death and enhanced control of S. Typhimurium in vivo. Thus, we propose that S. Typhimurium induces the production of type I interferon, which drives necroptosis of macrophages and allows them to evade the immune response.

Innate immunity is vital for the control of myriad pathogens early after infection, as well as for facilitating the development of acquired immune responses. However, some pathogens, such as Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium), have evolved mechanisms to evade innate immune responses1. In susceptible C57BL/6J mice, S. Typhimurium induces a lethal infection within 7 d, even at very low doses. Although mutation of the gene encoding the resistance-associated macrophage protein NRAMP-1 has been associated with enhanced susceptibility to S. Typhimurium infection2, S. Typhimurium is still able to establish chronic infection in mice with normal NRAMP-1 (ref. 3). Early control of S. Typhimurium is very much dependent on the induction of an appropriate innate immune response1, as antigen presentation and subsequent T cell responses to S. Typhimurium are not engaged early during infection4–6.

Macrophages control S. Typhimurium rapidly7,8, and induction of death in macrophages is a key virulence strategy used by intracellular bacteria, but the underlying mechanisms are yet to be fully elucidated9,10. In addition to apoptosis and necrosis, other mechanisms of cell death, such as pyroptosis, which is linked to inflammasome activation, and programmed necrosis mediated by the RIP family of serine-threonine kinases (necroptosis), have come to light11–13. Necroptosis is generally initiated by engagement of the TNFR1, a receptor for tumor-necrosis factor (TNF)14, which in turn activates RIP1 and RIP3 (ref. 15) and leads to necrotic cell death.

Inflammatory cytokines enhance the antimicrobial functions of macrophages and promote protection against intracellular pathogens16. The multimeric intracellular complex of the inflammasome, composed of pattern-recognition receptors of the NLR family, as well as the adaptor ASC and certain caspases, has been shown to form a molecular platform for activation of the cytokines interleukin 1β (IL-1β) and IL-18 (ref. 17), which also have a role in controlling pathogens18. Overactivation of inflammatory cytokines can induce pathology due to activation of programmed cell-death mechanisms.

The type I interferons IFN-α and IFN-β have an indispensable role in protection against viral infection by stimulating natural killer (NK) cells, promoting apoptosis of infected cells and facilitating acquired immune responses19. The expression of type I interferon leads to protection against extracellular bacteria such as group B streptococci, pneumococci and Escherichia coli20, whereas it exacerbates the outcome of infection with Listeria monocytogenes in mice21,22. Type I interferon can induce cell proliferation or death19,23 depending on the model and cells used, and therefore its functions have remained enigmatic. In this report, we have addressed the role of type I interferon signaling during infection of mice with S. Typhimurium. We found that S. Typhimurium exploited type I interferon signaling to eliminate macrophages, which resulted in a compromised innate immune response. We also obtained evidence that type I interferon signaling in macrophages drove RIP1- and RIP3-mediated necroptosis, which compromised pathogen control.

RESULTS

Type I interferon impairs control of S. Typhimurium

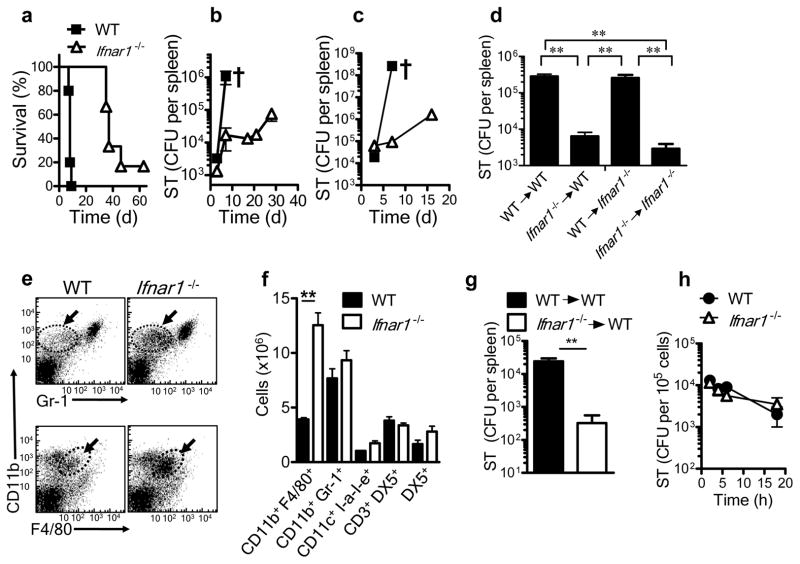

S. Typhimurium strain SL1344 is a highly virulent pathogen that causes a lethal infection in C57BL/6J mice even when used at a very low dose (1 × 102 bacteria). Host fatality may be attributable to impairment in the regulation of inflammatory cytokines. We thus evaluated the survival of wild-type mice and mice deficient in the receptor for IFN-α and IFN-β (IFNAR-deficient (Ifnar1−/−) mice, on the C57BL/6J background) after intravenous infection with S. Typhimurium. Ifnar1−/− mice had improved survival (Fig. 1a) and a much lower S. Typhimurium burden in spleen (Fig. 1b) relative to that of wild-type C57BL/6J mice, which showed that type I interferon signaling was detrimental to host survival during infection with S. Typhimurium. We obtained similar results for bacterial burden in the liver (data not shown). At later times, Ifnar1−/− mice showed a gradual increase in S. Typhimurium burden and eventually succumbed to infection (Fig. 1a,b). We also noted improved early control of S. Typhimurium in Ifnar1−/− mice infected by the intraperitoneal route (Fig. 1c). We also evaluated the survival of mice deficient in the expression of various other immunological mediators after infection with S. Typhimurium. Mice deficient in both TNFR1 and TNFR2, or iNOS2 or IFN-γ alone, had a slightly accelerated susceptibility to S. Typhimurium infection relative to that of wild-type mice, whereas the absence of IL-6 had no effect (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Prolonged survival of Ifnar1−/− mice to S. Typhimurium infection. (a–c) Survival (a) and bacterial burden in the spleen (b,c) of wild-type (WT) and Ifnar1−/− mice infected intravenously with 1 × 102 S. Typhimurium (ST; a,b) or intraperitoneally with 1 × 103 S. Typhimurium (c). † indicates death. CFU, colony-forming units. (d) Bacterial burden in the spleens of lethally irradiated wild-type or Ifnar1−/− recipient mice given bone marrow cells (1 × 107) from wild-type or Ifnar1−/− donors, then challenged 3 months later by intravenous infection with 1 × 102 S. Typhimurium and assessed at day 5 after infection. (e,f) Flow cytometry of cells in the spleens of wild-type and Ifnar1−/− mice 5 d after intravenous infection with 1 × 102 S. Typhimurium. Arrows and outlined areas in e indicate CD11b+Gr-1− cells (top row) or CD11b+F4/80+ cells (bottom row). (g) Bacterial burden in the spleens of naive wild-type mice given intravenous injection of bone marrow–derived macrophages from wild-type or Ifnar1−/− mice (5 × 106 cells), then challenged the next day by intraperitoneal infection with 1 × 102 S. Typhimurium and assessed 5 d after infection. (h) Intracellular survival of S. Typhimurium in bone marrow–derived macrophages after infection for 30 min in vitro (multiplicity of infection (MOI), 10). **P < 0.01 (one way ANOVA). Data are representative of two experiments with similar results, with three to five mice per group (mean and s.e.m. d,f–h).

We next evaluated whether the enhanced survival of Ifnar1−/− was mediated by cells of the immune system derived from the bone marrow. We gave wild-type and Ifnar1−/− mice a lethal dose of irradiation (12 Gy) and injected them with bone marrow cells from naive wild-type or Ifnar1−/− mice. At day 90 after cell transfer, we infected the recipient mice with S. Typhimurium and evaluated the bacterial burden 5 d later. Ifnar1−/− bone marrow cells that repopulated irradiated wild-type or Ifnar1−/− hosts induced significantly better protection against S. Typhimurium than did wild-type bone marrow cells (Fig. 1d). These results indicated involvement of hematopoietic cells in the better survival of Ifnar1−/− mice after infection with S. Typhimurium.

Control of S. Typhimurium by Ifnar1−/− macrophages

T cell activation is delayed during infection of mice with S. Typhimurium4–6, although susceptible (wild-type) mice die around day 7, before any substantial T cell response is detectable5. The considerably fewer colony-forming units present early in Ifnar1−/− hosts therefore suggested selective modulation of innate immune responses. We evaluated the spleens of mice 5 d after infection, assessing various cell types of the innate immune response by flow cytometry. There were significantly more macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+) in Ifnar1−/− spleens than in wild-type spleens (Fig. 1e,f). In contrast, there was no significant difference between wild-type and Ifnar1−/− mice in the number of NK cells, NKT cells, dendritic cells or neutrophils (Fig. 1f). Additionally, the cytotoxicity of NK cells from wild-type and Ifnar1−/− mice towards NK cell–sensitive target cells was similar (Supplementary Fig. 2a–c).

We next evaluated whether the enhanced control of S. Typhimurium in Ifnar1−/− mice was mediated specifically by macrophages. We generated macrophages from the bone marrow of naive wild-type and Ifnar1−/− mice through the use of macrophage colony-stimulating factor. These macrophages were F4/80hiCD11bhi and did not express the surface marker Ly6C or Gr-1 (data not shown). Ifnar1−/− macrophages transferred into naive wild-type hosts induced a significantly lower S. Typhimurium burden than did wild-type macrophages (Fig. 1g). Finally, we also evaluated whether Ifnar1−/− macrophages were intrinsically better at eliminating intracellular S. Typhimurium. We infected bone marrow–derived macrophages with S. Typhimurium in vitro and evaluated the intracellular bacterial burden at various time intervals. Wild-type and Ifnar1−/− macrophages mediated similar control of S. Typhimurium in vitro (Fig. 1h). Together our results indicated that the improved control of S. Typhimurium in vivo was related to the greater number of macrophages in Ifnar1−/− hosts and was not an intrinsic property of the Ifnar1−/− macrophages themselves.

Type I interferon signaling induces death of macrophages

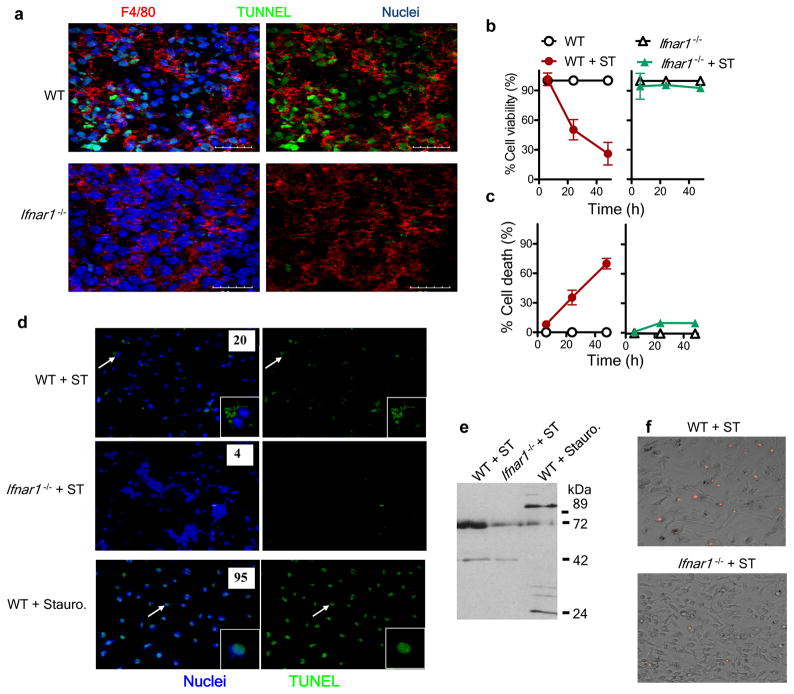

As the death of macrophages has been considered to be an essential mechanism of virulence of S. Typhimurium9, we assessed whether type I interferon signaling was coupled to cell death. We analyzed spleen sections by the TUNEL cell-death assay at day 5 after infection and costained the sections with antibody to F4/80 (anti-F4/80). We found more TUNEL+F4/80+ cells in wild-type spleens than in Ifnar1−/− spleens (Fig. 2a). We next did several in vitro experiments to precisely determine the modality of cell death. We infected wild-type and Ifnar1−/− macrophages with S. Typhimurium and evaluated viability after 24 and 48 h by a neutral red assay. Neutral red dye accumulates in the lysosomes of live cells; therefore, absorbance in this assay is directly proportional to the number of viable cells. Infection of wild-type macrophages with S. Typhimurium resulted in massive cell death; however, Ifnar1−/− macrophages resisted death after infection with S. Typhimurium (Fig. 2b). We further confirmed those results by measuring lactate dehydrogenase secreted into the medium after cell death (Fig. 2c). The death of wild-type macrophages was accelerated when they were preactivated with lipopolysaccharide (Supplementary Fig. 3a,b), in agreement with published reports24,25. However, even after preactivation with lipopolysaccharide, Ifnar1−/− macrophages remained highly resistant to S. Typhimurium–induced death. TUNEL staining of macrophages infected in vitro confirmed that Ifnar1−/− macrophages were less susceptible to S. Typhimurium–induced cell death than were wild-type macrophages (Fig. 2d). However, closer examination indicated that wild-type macrophages showed diffuse TUNEL staining, in contrast to the condensed chromatin staining typical of cells in which apoptosis has been induced by staurosporine (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2.

Ifnar1−/− macrophages are resistant to S. Typhimurium–induced cell death. (a) Confocal microscopy of frozen sections of spleens obtained from wild-type and Ifnar1−/− mice 5 d after intravenous infection with 1 × 102 S. Typhimurium and stained for F4/80 and by TUNEL. Scale bars, 20 μm. (b,c) Viability, assessed by uptake of neutral red (b), and death, assessed by lactate dehydrogenase–release assay (c), of wild-type and Ifnar1−/− bone marrow–derived macrophages plated in 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well and infected with S. Typhimurium (MOI, 10), then treated with gentamicin at 30 min after infection and assessed at 6, 24 and 48 h after infection. (d) Fluorescence microscopy of bone marrow–derived macrophages infected for 24 h with S. Typhimurium (+ ST) or treated for 3 h with staurosporine (+ stauro), then stained by TUNEL (green) and Hoechst nuclear dye (blue). Inset, enlargement of areas indicated by arrows. Original magnification, ×20 (main images) or ×60 (insets). Numbers in images indicate percent TUNEL+ cells (n ≥ 100 cells). (e) Immunoblot analysis of macrophages infected for 24h with S. Typhimurium or treated for 3 h with staurosporine, probed with antibody to cleaved PARP-1. (f) Fluorescence microscopy of bone marrow–derived macrophages infected for 24h with S. Typhimurium and stained with propidium iodide. Original magnification, ×20. Data are representative of three experiments with similar results (mean and s.e.m (b,c)).

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) is a nuclear enzyme that is cleaved to fragments of 89 kilodaltons (kDa) and 24 kDa in size during apoptosis26, whereas necrosis results in fragments approximately 72 kDa and 50 kDa in size26. We evaluated the PARP-1-cleavage pattern in wild-type and Ifnar1−/− macrophages infected with S. Typhimurium by immunoblot analysis with an antibody that specifically detects cleaved PARP-1. S. Typhimurium–infected macrophages had a cleavage pattern consistent with necrotic death (Fig. 2e). Moreover, the intensity of the bands, as indicated in the immunoblot, was less in case of Ifnar1−/− macrophages (Fig. 2e), indicative of less necrosis. Staining of S. Typhimurium–infected macrophages with propidium iodide further confirmed less death of Ifnar1−/− macrophages (Fig. 2f). Collectively, these data indicated that S. Typhimurium induced macrophage death via necrosis in a type I interferon–dependent manner.

Normal activation of Ifnar1−/− macrophages

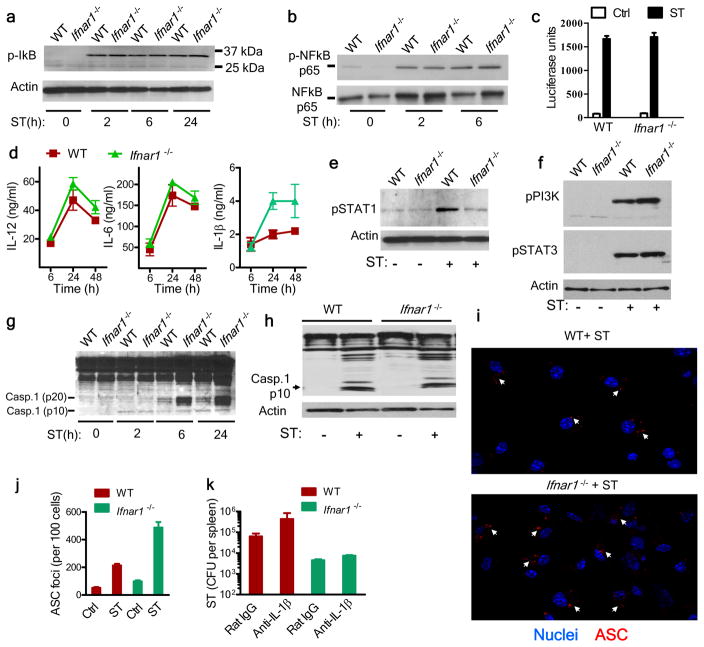

To evaluate modulation of activation of the transcription factor NF-κB, we infected bone marrow–derived macrophages with S. Typhimurium in vitro and assessed expression of the NF-κB inhibitor IκB. Wild-type and Ifnar1−/− macrophages had similar amounts of phosphorylated IκB and phosphorylated NF-κB subunit p65 (Fig. 3a,b). Wild-type and Ifnar1−/− macrophages also secreted similar amounts of type I interferon (Fig. 3c), IL-12 and IL-6 (Fig. 3d) after infection with S. Typhimurium. Furthermore, consistent with the canonical role of type I interferon signaling, Ifnar1−/− macrophages had minimal phosphorylation of the transcription factor STAT1 (Fig. 3e). Loss of type I interferon signaling did not alter the phosphorylation of STAT3 or phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase (Fig. 3f). Evaluation of the expression of cytokines and chemokines by macrophages by cytokine array did not show any impairment in cytokine expression by Ifnar1−/− macrophages in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 4a,b). These data indicated that cytokine signaling remained intact in Ifnar1−/− macrophages.

Figure 3.

Cytokine secretion and inflammasome activation are not impaired in Ifnar1−/− macrophages. (a,b) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated (p-) IκB (a) and total and phosphorylated NF-κB subunit p65 (b) in wild-type and Ifnar1−/− macrophages infected for various times (below lanes) with S. Typhimurium (MOI, 10). Actin serves as a loading control throughout. (c) Bioassay of type I interferon in supernatants of uninfected macrophages (control (Ctrl)) or macrophages infected for 24 h with S. Typhimurium (ST), assessed with the luciferase-expressing mouse fibroblast line L929-ISRE. (d) ELISA of IL-12, IL-6 and IL-1β in supernatants ofmacrophages infected for various times (horizontal axis) with S. Typhimurium. (e,f) Immunoblot analysis of STAT1 phosphorylated at Ser727 (e) and phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase (PI(3)K) phosphorylated at Tyr199 and STAT3 phosphorylated Tyr705 (f) in lysates of uninfected macrophages (ST −) or in macrophages 6 h after infection with S. Typhimurium (ST +). (g) Immunoblot analysis of the processing of caspase-1 (Casp1), probed with antibody to the caspase-1 p10 fragment. (h) Immunoblot analysis of caspase-1 in F4/80+ macrophages purified from the spleens of naive mice (ST −) and mice infected for 5 d with S. Typhimurium (ST +). (i) Confocal microscopy of macrophages grown on glass coverslips in 24 well-plates and infected for 30 min with S. Typhimurium (MOI, 10), then the extracellular bacteria were removed and cells cultured for 24h followed by fixation and staining with anti-ASC (red) and Hoechst nuclear stain (blue). Arrows indicate ASC foci. Original magnification, ×20. (j) Quantification of ASC foci in uninfected cells (Ctrl) (not shown) and in cells infected with ST as in i. (k) Bacterial burden in the spleens of mice infected intravenously with 1 × 102 S. Typhimurium, then given daily injection of rat immunoglobulin G (IgG) or neutralizing anti-IL-1β (100 μg per injection) for 4 d. Data are from one experiment with four mice per group (error bars (c,d,j,k), s.e.m.).

Inflammasomes are protein complexes that serve as molecular platforms for the activation of caspase-1, which in turn cleaves pro-IL-1β into its active form. S. Typhimurium can induce potent inflammasome activation in macrophages27; therefore, we measured the secretion of mature IL-1β by macrophages. After infection with S. Typhimurium, Ifnar1−/− macrophages released more IL-1β than did wild-type macrophages (Fig. 3d), indicative of enhanced inflammasome activation in Ifnar1−/− macrophages. Expression of IL-18 by WT or Ifnar1−/− macrophages was undetectable by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; data not shown). Immunoblot analysis of caspase-1 activation showed no substantial difference between in vitro–infected wild-type and Ifnar1−/− macrophages in abundance of the active p10 fragment of caspase-1 (Fig. 3g). Furthermore, activation of caspase-1 was similar in F4/80+ macrophages from wild-type and Ifnar1−/− mice infected in vivo (Fig. 3h). Staining of wild-type and Ifnar1−/− macrophages for ASC indicated slightly more ASC+ foci in Ifnar1−/− macrophages (Fig. 3i,j). Neutralization of IL-1β in vivo did not substantially influence the burden of S. Typhimurium in Ifnar1−/− mice (Fig. 3k). Together these results indicated that there was no apparent defect in Ifnar1−/− macrophages in terms of inflammasome activation or cytokine expression and that the resistance to S. Typhimurium infection observed in the Ifnar1−/− host seemed to be independent of IL-1β release.

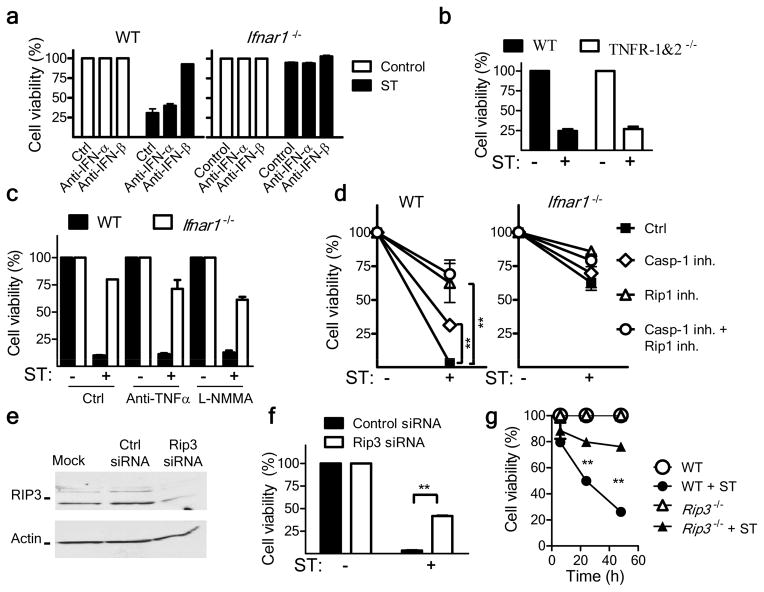

Type I interferon signaling induces RIP1-dependent cell death

We determined whether the type I interferon expressed by wild-type macrophages was directly responsible for their death. Thus, we measured cell death in the presence of neutralizing anti-IFN-α and anti-IFN-β antibodies. Although anti-IFN-α had no effect, anti-IFN-β prevented the death of wild-type macrophages (Fig. 4a). TNF and nitrate ions expressed by macrophages can also promote cell death; hence, we evaluated possible role of such factors in the death of wild-type macrophages. Macrophages deficient in both TNFR1 and TNFR2 were not resistant to death after infection with S. Typhimurium (Fig. 4b), and the addition of neutralizing anti-TNF antibody did not inhibit the death of wild-type macrophages (Fig. 4c). Similarly, treatment of cells with L-NMMA, which blocks the production of nitrite ions, failed to rescue wild-type macrophages from death (Fig. 4c). These results indicated that type I interferon signaling was directly responsible for the macrophage death induced after infection with S. Typhimurium. Given the atypical apoptosis of wild-type macrophages detected by TUNEL staining, we further investigated the mechanism of death. The addition of an inhibitor of caspase-1 (YVAD-CHO) resulted in significantly better survival of S. Typhimurium–infected wild-type macrophages (Fig. 4d), which suggested that caspase-1 contributed to the death of wild-type macrophages.

Figure 4.

Type I interferon induces necroptosis in S. Typhimurium–infected macrophages. (a) Viability of wild-type and Ifnar1−/− bone marrow–derived macrophages incubated with no antibody (No Ab) or neutralizing anti-IFN-α or anti-IFN-β (10 μg/ml) and left uninfected (ST −) or infected for 48 h with S. Typhimurium (ST +), assessed by neutral red assay. (b) Viability of bone marrow–derived macrophages from wild-type mice (WT) and mice deficient in TNFR1 and TNFR2 (TNFR-KO), infected for 48 h with S. Typhimurium, assessed by neutral red assay. (c) Viability of macrophages left untreated (Ctrl) or incubated with anti-TNF (20 μg/ml) or L-NMMA (20 μg/ml) during S. Typhimurium infection for 48 h, assessed as in b. (d) Viability of macrophages cultured with no inhibitors (Ctrl) or with an inhibitor of caspase-1 (Casp1 inh; 50 μM) or RIP1 (RIP1 inh; 33 μM) or both inhibitors and left uninfected (ST −) or infected for 48 h with S. Typhimurium (ST +), presented relative to that of inhibitor-treated uninfected cells. (e) Immunoblot analysis of RIP3 in the commonly used mature macrophage cell line (J774A.1) mock transfected (Mock) or transfected for 24 h with control or RIP3-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA). (f) Viability of macrophages transfected as in e, then infected for 24 h with S. Typhimurium, assessed as in b. (g) Viability of wild-type and Rip3−/− macrophages infected and assessed as in b. **P < 0.01 (two-way ANOVA). All experiments involved analysis of triplicate samples from a single experiment, and data is representative of two to three similar experiments. (a–g; error bars, s.e.m.).

An additional pathway of programmed necrosis called ‘necroptosis’ has been described28. Normally, necroptosis is induced through TNF-mediated activation of kinases of the RIP family14 and can be specifically blocked through the use of necrostatin, which targets the RIP1 kinase domain29. Treatment of S. Typhimurium–infected macrophages with necrostatin resulted in substantial inhibition of the death of wild-type macrophages (Fig. 4d). RIP1 has been shown to form a phosphorylation complex with RIP3 to activate necroptosis30,31. Therefore, we evaluated whether S. Typhimurium–induced macrophage death could be prevented by knockdown of RIP3 in macrophages. RIP3-specific small interfering RNA diminished RIP3 expression (Fig. 4e) and significantly abrogated the S. Typhimurium–induced death of wild-type macrophages (Fig. 4f). Macrophages from RIP3-deficient mice (Ripk3−/− mice; called ‘Rip3−/−’ mice here, on a C57BL/6J background) also underwent less S. Typhimurium–induced death (Fig. 4g), similar to cells from Ifnar1−/− mice. These results showed that S. Typhimurium also used the mechanism of necroptosis to induce macrophage death. We also noted this mechanism of death in macrophages infected with L. monocytogenes (Supplementary Fig. 5), which suggested that necroptosis seems to be an important cell-death mechanism induced by intracellular bacterial pathogens to escape innate immune defense.

Activation of RIP1 and RIP3 during S. Typhimurium infection

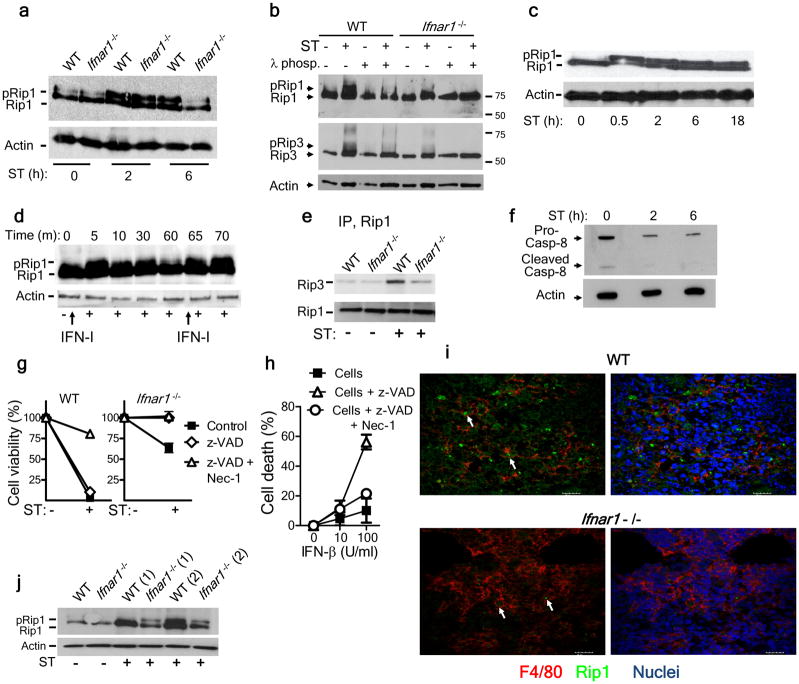

We next evaluated the expression of RIP1 and RIP3 in macrophages infected with S. Typhimurium in vitro. Although RIP1 was expressed by wild-type and Ifnar1−/− bone marrow–derived macrophages, S. Typhimurium–infected Ifnar1−/− macrophages had less-intense bands for the phosphorylated forms of RIP1 and RIP3 (ref. 32) by immunoblot analysis, particularly at later time periods (Fig. 5a,b). We confirmed that the bands that migrated more slowly were the phosphorylated forms of RIP1 and RIP3, as these bands disappeared after treatment with λ-phosphatase (Fig. 5b). Of note, we were unable to detect phosphorylation of RIP3 at 2 or 6 h after infection of macrophages with S. Typhimurium, consistent with the delayed-death phenotype we observed in cell-viability experiments (data not shown). When we infected IC-21 macrophages (simian virus 40–transformed mouse macrophages on the C57BL/6 background) with S. Typhimurium or incubated them with type I interferon, RIP1 phosphorylation was induced (Fig. 5c,d). Maintenance of RIP1 phosphorylation required prolonged exposure to type I interferon or infection with S. Typhimurium (Fig. 5c,d). Infection of macrophages with S. Typhimurium led to the induction of RIP3 expression (Fig. 5b), which suggested a shift toward necroptosis. When we immunoprecipitated RIP1, we observed a stronger association of RIP3 with RIP1 in wild-type macrophages than in Ifnar1−/− macrophages, after infection with S. Typhimurium (Fig. 5e). Caspase-8 is a central inhibitor of necroptosis, and blockade of caspase-8 leads to cell death by necroptosis33. Immunoblot analysis showed that there was less caspase-8 present after infection with S. Typhimurium (Fig. 5f). When caspase activity was blocked, engagement of the IFNAR receptor for IFN-α and IFN-β resulted in death of macrophages by necroptosis (Fig. 5g,h). These data indicated that type I interferon–induced necroptosis was dependent on the inhibition of caspase activity.

Figure 5.

Infection of macrophages with S. Typhimurium leads to type I interferon–dependent phosphorylation of RIP1 and RIP3. (a) Immunoblot analysis of total and phosphorylated RIP1 in lysates of uninfected macrophages (ST 0 h) or macrophages infected for 2 or 6 h (below lanes) with S. Typhimurium. (b) Immunoblot analysis of total and phosphorylated RIP1 and RIP3 lysates of uninfected macrophages (ST −) or macrophages infected for 24 h with S. Typhimurium (ST +), with (+) or without (−) treatment of lysates with λ-phosphatase (λ-phos). (c,d) Immunoblot analysis of total and phosphorylated RIP1 in lysates of IC-21 macrophages infected with S. Typhimurium (MOI, 10; c) or cultured with type I interferon as indicated by arrows pointing upwards (d). (e) Immunoblot analysis of lysates of S. Typhimurium–infected macrophages after immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-RIP1, probed with anti-RIP3 or anti-RIP1. (f) Immunoblot analysis of lysates for the processing of caspase-8 in uninfected and S. Typhimurium–infected wild-type macrophages. (g) Viability of wild-type and Ifnar1−/− macrophages left untreated (Ctrl) or treated with the antiapoptotic compound z-VAD alone (z-VAD) or z-VAD and necrostatin (z-VAD + Nec-1) and left uninfected or infected with S. Typhimurium, assessed by neutral red assay. (h) Death of uninfected J774 macrophages treated as in g (key) in the presence of various concentrations of IFN-β (horizontal axis), assessed as in g. (i) Confocal microscopy of frozen sections of spleens from mice 5 d after intravenous infection with 1 × 102 S. Typhimurium, immunostained for F4/80 (red) and RIP1 (green) and with Hoechst nuclear dye (blue). Arrows indicate RIP1 expression in macrophages. Scale bars, 20 μm. (j) Immunoblot analysis of total and phosphorylated RIP1 in lysates of F4/80+ macrophages purified from the spleens of uninfected mice or mice 5 d after infection with S. Typhimurium. RIP1 expression was measured in macrophages purified from two mice (1 and 2).Data are representative of 2 (a,b,f,g,h,j,j) or 3 (c,d,e) experiments (error bars (g,h), s.e.m.).

To further confirm the critical role of necroptosis, we evaluated RIP1 expression in vivo at day 5 after infection with S. Typhimurium. We stained wild-type and Ifnar1−/− spleen cells for F4/80 and RIP1 and found that wild-type spleen sections had more intense staining for RIP1 than did Ifnar1−/− spleen sections (Fig. 5i). We then evaluated the expression of RIP1 on splenic F4/80+ macrophages by immunoblot analysis. Similar to the results obtained with bone marrow–derived macrophages, Ifnar1−/− splenic macrophages had less phosphorylation of RIP1 at day 5 after infection than did wild-type cells (Fig. 5j). These results suggest that RIP1 signaling mediated by IFNAR may be a key, as-yet-unknown pathway of macrophage death.

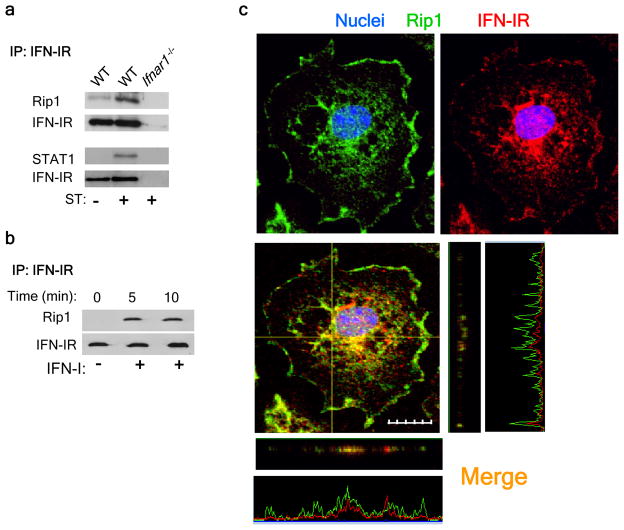

Type I interferon induces a RIP1-IFNAR association

Having identified considerable differences in the activation of RIP1 in the absence of IFNAR signaling, we hypothesized that RIP1 may interact directly with IFNAR in a manner similar to the TNFR-RIP1 interaction14. We infected wild-type macrophages with S. Typhimurium and immunoprecipitated IFNAR, then analyzed the precipitates by immunoblot with anti-RIP1. RIP1 was immunoprecipitated along with IFNAR, and this association was enhanced after infection (Fig. 6a). To further confirm that the interaction of RIP1 with IFNAR was strictly induced by engagement of IFNAR, we treated macrophages with type I interferon and immunoprecipitated IFNAR at various times. Immunoblot analysis indicated that the association of RIP1 with IFNAR increased within 5 min of treatment with type I interferon (Fig. 6b). Furthermore, staining for RIP1 and IFNAR on S. Typhimurium–infected wild-type macrophages showed localization of RIP1 together with IFNAR (Fig. 6c). Together these results indicated that type I interferon promoted the formation of a RIP1-RIP3 complex, which led to necroptosis.

Figure 6.

Engagement of IFNAR leads to necroptosis. (a,b) Immunoassay of wild-type and Ifnar1−/− bone marrow–derived macrophages left uninfected or infected for 6 h with S. Typhimurium (a) or of IC-21 macrophages left untreated or treated with IFN-β (5,000 U/ml; b), immunoprecipitated with anti-IFNAR and analyzed by immunoblot with anti-RIP1 (a,b) and anti-STAT1 (a). (c) Confocal microscopy of wild-type bone marrow–derived macrophages grown on glass coverslips in 24 well-plates and infected for 30 min with S. Typhimurium (MOI, 10), then incubated for 24 h in gentamicin-containing media, fixed and stained with anti-IFNAR (red) and anti-RIP1 (green) and Hoechst (blue). The picture shows the 3 planes of the recorded z-stack image. The x and y planes are represented by the yellow lines drawn in the microscopic image. The z-plane corresponding to the x and y planes are represented in the horizontal and vertical image to the bottom and right of the microscopic image respectively. Original magnification, × 60.; scale bar, 10 μm. Data are representative of 3 (a,b) or 2 (c) experiments.

Macrophage necroptosis limits pathogen control

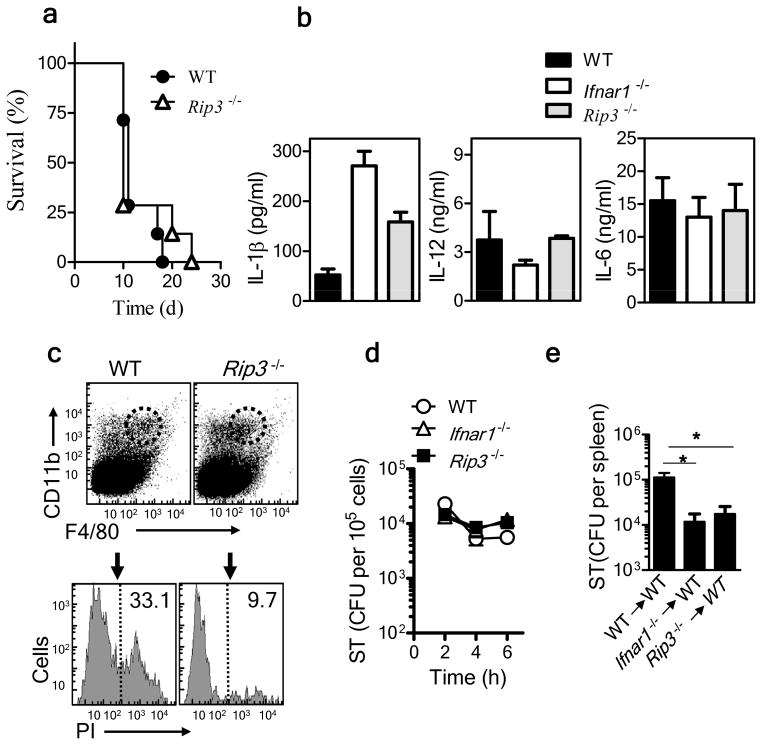

We assessed the general importance of necroptosis in the pathogenesis of S. Typhimurium through the use of necroptosis-resistant cells from Rip3−/− mice. Unlike the Ifnar1−/− mice, Rip3−/− mice did not show any substantial difference in survival relative to that of wild-type C57BL/6J mice during infection with S. Typhimurium (Fig. 7a). After infection with a high bacterial dose (1 × 105 S. Typhimurium injected intravenously), the bacterial burden at 24 h after infection was similar in wild-type, Ifnar1−/− and Rip3−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Cytokine expression, as determined by cytokine array, was similar in the serum of Ifnar1−/− and Rip3−/− mice at 24 h after infection (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Similarly, in vitro infection of macrophages with S. Typhimurium resulted in similar cytokine pattern in Ifnar1−/− and Rip3−/− cells (Fig. 7b). Despite the similar survival of Rip3−/− and wild-type mice, we observed much less death of F4/80+ macrophages in S. Typhimurium–infected spleens from Rip3−/− mice than of those from wild-type mice, as assessed by staining with propidium iodide (Fig. 7c). Macrophages derived from the bone marrow of wild-type, Ifnar1−/− and Rip3−/− mice showed similar control of S. Typhimurium in vitro (Fig. 7d). Transfer of Rip3−/− macrophages into wild-type hosts resulted in significantly better control of S. Typhimurium than did the transfer of wild-type macrophages, and it was similar to that seen with Ifnar−/− macrophages (Fig. 7e). The cIAP proteins are also known to limit necroptosis by inhibiting RIP1 (ref. 33); consistent with that, cIAP expression has been shown to protect macrophages from necroptosis during infection with L. monotytogenes34. Furthermore, consistent with a model whereby more necroptosis of macrophage leads to impaired control of S. Typhimurium, cIAP1-deficient mice had a substantially higher S. Typhimurium burden than that of wild-type mice (Supplementary Fig. 7). Overall, these results indicated necroptosis was a mechanism of type I interferon–dependent, S. Typhimurium–induced macrophage death.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of necroptosis in macrophages leads to less macrophage death and enhanced bacterial control. (a) Survival of wild-type and Rip3−/− mice after intravenous infection with 1 × 102 S. Typhimurium. (b) ELISA of IL-1β, IL-12 and IL-6 in supernatants of wild-type, Ifnar1−/− and Rip3−/− bone marrow–derived macrophages infected for 48 h in vitro with S. Typhimurium (MOI, 10). (c) Flow cytometry of spleen cells obtained from wild-type and Rip3−/− mice 3 d after intravenous infection with 1 × 102 S. Typhimurium and stained with anti-CD11b and anti-F4/80 (top), followed by staining of CD11b+F4/80+ macrophages (dashed outline, top) with propidium iodide (PI) for analysis of cell death (bottom). [Numbers at right of dashed vertical lines (bottom) indicate percent propidium iodide–positive dead cells. (d) Bacterial burden in wild-type, Ifnar1−/− and Rip3−/− macrophages at various times after in vitro infection with S. Typhimurium. (e) Bacterial burden in the spleens of naive wild-type mice given intravenous injection of wild-type, Ifnar1−/− or Rip3−/− bone marrow–derived macrophages (5 × 106 cells per mouse), then challenged intraperitoneally with 1 × 102 S. Typhimurium and assessed 5 d after infection. *P < 0.05 (one way ANOVA).Data are representative of 2 experiments (a–e). Error bars (b,d,e);s.e.m.).

DISCUSSION

Pathogens are controlled by an early innate immune response, followed by a targeted adaptive immune response. However, virulent and evasive pathogens such as S. Typhimurium and mycobacteria can elicit a delayed adaptive immune response4–6,35. Thus, immunological protection against such pathogens relies heavily on effective innate immune responses. In this study we have shown that S. Typhimurium exploited type I interferon, an indispensable antiviral cytokine19, to induce necroptosis of macrophages and promote its own pathogenesis.

The role of type I interferons in bacterial infection seems to be pathogen dependent. Expression of type I interferons correlates with the production of IFN-γ, nitrogen dioxide and TNF and protection against extracellular bacteria such as group B streptococci, pneumococci and E. coli20. Conversely, expression of type I interferons exacerbates the infection of mice with the intracellular pathogen L. monocytogenes21,22. Enhanced resistance to L. monocytogenes in IFNAR-deficient mice correlates with IFN-γ and IL-12 expression21 and inhibition of the expression of genes encoding proapoptotic molecules22. Although we did not notice any specific modulation of IL-12 or IFN-γ in Ifnar1−/− mice relative to their expression in wild-type mice, there was much higher expression of IL-1β in Ifnar1−/− macrophages. We observed no substantial effect on the bacterial burden by neutralization of IL-1β. Thus, although our results add to an evidence suggesting complex cross-regulation of IL-1β and the necroptosis signaling machinery36,37, it remains unclear whether the type I interferon–mediated dysfunction of macrophages in S. Typhimurium infection is cytokine dependent.

Rapid death of macrophages induced by S. Typhimurium has been considered an essential mechanism of its virulence9. Apoptosis has been shown to be the main mechanism of death in S. Typhimurium–infected intestinal epithelial cells38. In addition, S. Typhimurium is also reported to induce caspase-1-dependent death in macrophages, called ‘pyroptosis’12,25,27. S. Typhimurium–induced pyroptosis has also been shown to aid in the dissemination of bacteria from the gut to the tissues39. In contrast, deficiency in caspase-1 or components of inflammasome has also been reported to enhance susceptibility to infection40,41. Consistent with published studies27, we observed some prevention of cell death after inhibition of caspase-1 in vitro. Nevertheless, inhibition of RIP1 was much more effective than inhibition of caspase-1 in rescuing S. Typhimurium–infected cells from death, which indicated the possibility of additional molecular mediators of death in S. Typhimurium–infected macrophages. It is likely that there may be points of molecular interaction between the pathways of the inflammasome and necroptosis that are as yet undetermined.

It has been suggested that the elimination of macrophages by inflammasome activation may promote host survival24. Unlike epithelial cells, macrophages do not allow Salmonella to replicate much5. Eliminating macrophages through necroptosis early in infection may promote susceptibility, as bacteria can replicate rapidly in the extracellular milieu. It is likely that during the chronic stage, during which the bacteria are confined mainly to the intracellular compartment, elimination of infected macrophages may be beneficial. Thus, macrophages may have a dichotomous role depending on the stage of infection.

We have shown here that IFNAR specifically associated with RIP1 after type I interferon signaling. Although this is the first report to our knowledge showing direct effects on RIP1 by type I interferon, a published study has identified many members of the interferon gene family as ‘hits’ in a genome-wide screen to identify the regulators of necroptosis14. Nevertheless, treatment of macrophages with type I interferon alone did not result in sustained RIP1 activation or cell death. This was possibly due to a cell-intrinsic mechanism keeping RIP1 activation under control. Caspase-8 is considered the canonical inhibitor of kinases of the RIP family and necroptosis42, with necroptosis being detected only when caspase-8 activity is blocked33. Consistent with that, our results indicated that S. Typhimurium infection also led to downregulation of caspase-8, which then allowed type I interferon–induced RIP1 to promote necroptosis.

In addition to the role of type I interferon in the phosphorylation of RIP1, other pathways may aid in the full-blown activation of necroptosis. Signaling via Toll-like receptor 3 or Toll-like receptor 4 has been shown to activate the phosphorylation of RIP1 through the pathway of the adaptor TRIF43. Given its published role in necroptosis, we hypothesized that TNF28 might have a role in S. Typhimurium–induced cell death. Our evidence, both in vivo and in vitro, did not support that proposal. Thus, although our results did not preclude the possibility that additional mechanisms may aid in the activation of necroptotic cell death, we have shown that type I interferon was a key regulator in the necrotic cell death induced by S. Typhimurium.

It is possible that the pathway of necroptosis13 is prevalent during other infections. Vaccinia virus expressing a homolog of CrmA that is able to inhibit caspases induces necrosis in adipocytes and hepatocytes15. M45, a protein expressed by cytomegalovirus, has also been shown to block RIP1 activity and disrupt the RIP1-RIP3 interaction44,45.

S. Typhimurium has been shown to induce the expression of type I interferon by macrophages46. Elimination of macrophages by type I interferon signaling may therefore compromise their vital role in innate immunity. Moreover, it is likely that the manner in which a cell dies can influence the induction of subsequent inflammation and pathogen control. Although some inflammation is needed, hyperactivation of inflammation can misdirect appropriate host responses and can potentially cause dangerous pathology. Modulation of innate immunity during pregnancy or by treatment with the dinucleotide CpG can lead to a catastrophic outcome, even in mice that are normally resistant (129X1SvJ) to S. Typhimurium infection 47,48. A role for signaling via both type I interferon and the tumor suppressor protein, TRP53 in the pathogenesis of Salmonella infection has been demonstrated through the use of a genetics approach49. Thus, we propose a model by which S. Typhimurium exploits the host type I interferon response to eliminate macrophages through RIP-dependent cell death and promote its own survival. Type I interferon is expressed during viral infection, in which it has a critical role in control of infection. Chronic exposure to type I interferon may predispose hosts to infections with intracellular bacteria. Indeed, systemic disease caused by non-typhoidal Salmonella is resurfacing in epidemic proportions in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus in Africa50. Finding new approaches for preventing necroptosis may be a viable option for the treatment of chronic infection.

ONLINE METHODS

Mice and infection

Mice were housed in the animal facility of the National Research Council Institute for Biological Sciences. Procedures were approved by the institutional Animal Care Committee. C57BL/6J mice were from The Jackson Laboratory. Ifnar−/− mice were from K. Murali-Krishna. Rip3−/− mice were provided by V. Dixit. For infection, frozen stocks of S. Typhimurium (SL1344) were thawed and then diluted in 0.9% NaCl. Mice were infected with 1 × 102 S. Typhimurium suspended in 200 μl of 0.9% NaCl, intravenously via the lateral tail vein or via intraperitoneal injection.

Bacterial burden

Serial dilutions of spleen cell suspensions (in RPMI medium) were plated on brain-heart infusion agar plates. After overnight incubation at 37 °C, colony-forming units were counted.

Bone marrow macrophages

Bone marrow from wild-type, Ifnar−/− or Rip3−/− mice was flushed with RPMI medium. Cells (1 × 106 cells per ml) were seeded in RPMI medium containing 8% FBS in tissue culture flasks and were allowed to differentiate for 7 d into macrophages in the presence of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (5 ng/ml). Nonadherent cells were removed on days 2 and 4, and adherent macrophages were used from day 7 onwards.

Splenic macrophages

A Stem Cell PE selection kit was used for the purification of F4/80+ cells, as described by the manufacturer (STEMCELL Technologies).

Flow cytometry

Aliquots of cell suspensions (1 × 107 cells resuspended in 1%BSA in PBS) were incubated with Fc Block (2.4G2; BD Biosciences) and various combinations of the following antibodies: anti-CD49b (DX5; BD Biosciences), anti-CD3 (145-2C11; BD Biosciences), anti-F4/80 (C1:A3-1; BioLegend), anti-CD11b (M1/70; BD Biosciences), anti-CD11c (HL3; BD Biosciences) and anti-Gr-1 (RB6-8C5; BD Biosciences). Cells were resuspended in 0.5% fixative and data were acquired on FACSCanto (BD) and analyzed with FACSDiva software (BD).

Antibodies and cytokine assays

Neutralizing anti-IFN-α (RMMA-1) and IFN-β (RMMB-1) were from PBL Interferon Source. Neutralizing anti-TNF (G281-2626) was from BD Biosciences. Neutralizing anti-IL-1β (B122) was from eBioscience. IL-6 and IL-12 were measured by sandwich ELISA (BD Biosciences). IL-1β was assayed with a mouse IL-1β DuoSet ELISA kit (R&D Systems). Type I interferon was measured in an L929 cell line (obtained from B. Beutler) with a luciferase reporter gene cloned under the regulation of an interferon-stimulated response element promoter. These ISRE-L929 cells (5 × 104 cells per well in 96-well plates) were incubated for 4 h with 40 μl cell culture supernatant from un-nfected or cells infected with S. Typhimurium. Cells were then lysed and luciferase activity was determined with a Luciferase Assay System according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega).

Inhibitors

The caspase-1 inhibitor YVAD-CHO (Tyr-Val-Ala-Asp–aldehyde) was from Calbiochem; necrostatin-1 was from Sigma.

In vitro infection

Macrophages were infected as described5. Cells were seeded into tissue culture plates and infected with S. Typhimurium (MOI, 10). After 30 min, extracellular bacteria were removed by washing of cells in RPMI medium plus 8% FBS containing a high concentration of gentamicin (50 μg/ml). Cells were incubated for 2 h, and then were washed and subsequently cultured in medium containing less gentamicin (10 μg/ml). At various times, the intracellular bacterial burden was evaluated after lysis of cells (with 1% Triton X100 and 0.1% SDS in PBS, pH 7.2) and plating of appropriate dilutions (in saline) on brain-heart infusion agar plates.

Cell-death assay

Macrophages were infected in vitro as described above. At various times (6–48 h), medium was collected for analysis of the release of lactate dehydrogenase, and neutral red was added to the cells, followed by incubation for 4 h. The dye was then removed and cells were fixed with fixative. Neutral red dye that had accumulated in live cells was then released with lysis buffer. The absorbance of the released dye is directly proportional to the number of viable cells, which was quantified by colorimetric analysis at 570 nm. A TUNEL staining kit (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Roche) for characterization of apoptosis.

Immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing protease inhibitors. After cell lysates were cleared for 1 h with protein G agarose beads (GE Healthcare Life Sciences), beads were removed by centrifugation and whole-cell lysates (approximately 500 μg protein) were treated for 18 h with 4 μg anti-IFNAR (MAR1-5A3; Leinco Technologies) or anti-RIP1 (38; BD Transduction Laboratories). Protein G agarose beads were then added, followed by incubation for an additional 1 h. Immunoprecipitated proteins, along with the agarose beads, were collected by centrifugation.

Immunoblot analysis

Radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer without phosphatase inhibitors was used for the λ-phosphatase assay, according to manufacturer’s protocol (P9614; Sigma). Samples were mixed 1:1 with 2× sample loading buffer, were boiled at 95 °C and were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were then transferred on to a PVDF membrane; nonspecific binding was blocked with 5% milk or BSA and membranes were probed with the following primary antibodies followed by treatment with the appropriate secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. Antibody to STAT1 phosphorylated at Ser727 (#9177), STAT3 phosphorylated at Tyr705 (#9131), phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase phosphorylated at Tyr199 (#4228), anti-caspase-8 (#4927) and anti-IκBα (#9246) were from Cell Signaling; antibody to caspase-1 p10 (Sc-514(M-20)) and secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP:sc-2004 and rabbit anti-mouse IgG-HRP: sc-358923) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Blots were developed with an enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (BioRad) and bands were identified by exposure of the membrane to X-ray film (Kodak, Care Stream Health).

Confocal microscopy

Cells were fixed and then Fc gamma receptors were blocked with 10% normal goat serum in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100. Cells were probed overnight at 4 °C with anti-IFNAR (MAR1-5A3; Leinco) and anti-RIP1 (#3493; Cell Signaling). Unconjugated antibodies were stained with Alexa Fluor 594– and Alexa Fluor 488–tagged goat antibody to mouse and rabbit (F(ab′)2 fragment), respectively (A-11020 and A11070; Invitrogen). Cells were washed with PBS containing 0.03% Triton-X100 and nuclei were stained with Hoechst. For splenic sections, spleens were embedded in optimum cutting temperature compound and were frozen in liquid nitrogen. Sections (10 μm in thickness) were fixed with methanol and probed with anti-F4/80 (BM8, eBioscience) and anti-RIP1 (#3493, Cell Signaling). Staining and processing were done as described above. Coverslips were mounted on slides with ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen) and were imaged with an Olympus Fluoview FV1000 confocal microscope.

Cytokine array

Expression of cytokines and chemokines was evaluated by Proteome Array kit (R&D Systems) with a chemiluminescence-based detection system (Fluorochem 8900 imager; Alpha Innotech). Densitometry was assessed with AlphaEase software and values were corrected to those of the internal positive controls.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Murali-Krishna (Emory University) for Ifnar−/− mice; V. Dixit (Genentech) for Rip3−/− mice; B. Beutler (UT Southwestern) for the L929-ISRE cell line; and S. Thurston for technical help. Supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (S.S.), the Ontario Institute of Cancer Research (L.K.) and the National Research Council of Canada.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://www.nature.com/reprints/index.html.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

N.R., S.M., R.M. and R.D. performed experimens and analyzed the data. N.R., S.M., L.K., S.S., designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. S.S and L.K. conceptualized the project, obtained research funding and provided reagents.

References

- 1.Jones BD, Falkow S. Salmonellosis: host immune responses and bacterial virulence determinants. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:533–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vidal S, et al. The Ity/Lsh/Bcg locus: natural resistance to infection with intracellular parasites is abrogated by disruption of the Nramp1 gene. J Exp Med. 1995;182:655–666. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.3.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sad S, et al. Pathogen proliferation governs the magnitude but compromises the function of CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:5853–5861. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luu RA, et al. Delayed expansion and contraction of CD8+ T cell response during infection with virulent Salmonella typhimurium. J Immunol. 2006;177:1516–1525. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albaghdadi H, Robinson N, Finlay B, Krishnan L, Sad S. Selectively reduced intracellular proliferation of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium within APCs limits antigen presentation and development of a rapid CD8 T cell response. J Immunol. 2009;183:3778–3787. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vidric M, Bladt AT, Dianzani U, Watts TH. Role for inducible costimulator in control of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection in mice. Infect Immun. 2006;74:1050–1061. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.2.1050-1061.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Brien AD, Scher I, Formal SB. Effect of silica on the innate resistance of inbred mice to Salmonella typhimurium infection. Infect Immun. 1979;25:513–520. doi: 10.1128/iai.25.2.513-520.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salcedo SP, Noursadeghi M, Cohen J, Holden DW. Intracellular replication of Salmonella typhimurium strains in specific subsets of splenic macrophages in vivo. Cell Microbiol. 2001;3:587–597. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindgren SW, Stojiljkovic I, Heffron F. Macrophage killing is an essential virulence mechanism of Salmonella typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4197–4201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stockinger S, Decker T. Novel functions of type I interferons revealed by infection studies with Listeria monocytogenes. Immunobiology. 2008;213:889–897. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hersh D, et al. The Salmonella invasin SipB induces macrophage apoptosis by binding to caspase-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2396–2401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brennan MA, Cookson BT. Salmonella induces macrophage death by caspase-1-dependent necrosis. Mol Microbiol. 2000;38:31–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Degterev A, et al. Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:112–119. doi: 10.1038/nchembio711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hitomi J, et al. Identification of a molecular signaling network that regulates a cellular necrotic cell death pathway. Cell. 2008;135:1311–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho YS, et al. Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1–RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell. 2009;137:1112–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scharton KT, Afonso LC, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Scott P. IL-12 is required for natural killer cell activation and subsequent T helper 1 cell development in experimental leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 1995;154:5320–5330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gross O, Thomas CJ, Guarda G, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: an integrated view. Immunol Rev. 2011;243:136–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dinarello CA. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:519–550. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biron CA. Interferons α and β as immune regulators–a new look. Immunity. 2001;14:661–664. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mancuso G, et al. Type I IFN signaling is crucial for host resistance against different species of pathogenic bacteria. J Immunol. 2007;178:3126–3133. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Auerbuch V, Brockstedt DG, Meyer-Morse N, O’Riordan M, Portnoy DA. Mice lacking the type I interferon receptor are resistant to Listeria monocytogenes. J Exp Med. 2004;200:527–533. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Connell RM, et al. Type I interferon production enhances susceptibility to Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Exp Med. 2004;200:437–445. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thyrell L, et al. Interferon α-induced apoptosis in tumor cells is mediated through the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24152–24162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312219200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miao EA, et al. Caspase-1-induced pyroptosis is an innate immune effector mechanism against intracellular bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:1136–1142. doi: 10.1038/ni.1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mariathasan S, et al. Differential activation of the inflammasome by caspase-1 adaptors ASC and Ipaf. Nature. 2004;430:213–218. doi: 10.1038/nature02664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gobeil S, Boucher CC, Nadeau D, Poirier GG. Characterization of the necrotic cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP-1): implication of lysosomal proteases. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8:588–594. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fink SL, Cookson BT. Pyroptosis and host cell death responses during Salmonella infection. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:2562–2570. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galluzzi L, Kroemer G. Necroptosis: a specialized pathway of programmed necrosis. Cell. 2008;135:1161–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Degterev A, et al. Identification of RIP1 kinase as a specific cellular target of necrostatins. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:313–321. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He S, et al. Receptor interacting protein kinase-3 determines cellular necrotic response to TNF-α. Cell. 2009;137:1100–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vanlangenakker N, et al. cIAP1 and TAK1 protect cells from TNF-induced necrosis by preventing RIP1/RIP3-dependent reactive oxygen species production. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:656–665. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee TH, Shank J, Cusson N, Kelliher MA. The kinase activity of Rip1 is not required for tumor necrosis factor-α-induced IκB kinase or p38 MAP kinase activation or for the ubiquitination of Rip1 by Traf2. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33185–33191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vandenabeele P, Declercq W, Van Herreweghe F, Vanden Berghe T. The role of the kinases RIP1 and RIP3 in TNF-induced necrosis. Sci Signal. 2010;3:re4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3115re4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McComb S, et al. cIAP1 and cIAP2 limit macrophage necroptosis by inhibiting Rip1 and Rip3 activation. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19 doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.59. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Faassen H, Dudani R, Krishnan L, Sad S. Prolonged antigen presentation, APC−, and CD8+ T cell turnover during mycobacterial infection: comparison with Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol. 2004;172:3491–3500. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vince JE, et al. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins limit RIP3 kinase-dependent interleukin-1 activation. Immunity. 2012;36:215–227. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Labbé K, McIntire CR, Doiron K, Leblanc PM, Saleh M. Cellular inhibitors of apoptosis proteins cIAP1 and cIAP2 are required for efficient caspase-1 activation by the inflammasome. Immunity. 2011;35:897–907. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knodler LA, Finlay BB. Salmonella and apoptosis: to live or let die? Microbes Infect. 2001;3:1321–1326. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01493-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monack DM, et al. Salmonella exploits caspase-1 to colonize Peyer’s patches in a murine typhoid model. J Exp Med. 2000;192:249–258. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lara-Tejero M, et al. Role of the caspase-1 inflammasome in Salmonella typhimurium pathogenesis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1407–1412. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raupach B, Peuschel SK, Monack DM, Zychlinsky A. Caspase-1-mediated activation of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18 contributes to innate immune defenses against Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4922–4926. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00417-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oberst A, et al. Catalytic activity of the caspase-8-FLIPL complex inhibits RIPK3-dependent necrosis. Nature. 2011;471:363–367. doi: 10.1038/nature09852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.He S, Liang Y, Shao F, Wang X. Toll-like receptors activate programmed necrosis in macrophages through a receptor-interacting kinase-3-mediated pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:20054–20059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116302108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Upton JW, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski ES. Virus inhibition of RIP3-dependent necrosis. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:302–313. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mack C, Sickmann A, Lembo D, Brune W. Inhibition of proinflammatory and innate immune signaling pathways by a cytomegalovirus RIP1-interacting protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3094–3099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800168105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sing A, et al. Bacterial induction of β interferon in mice is a function of the lipopolysaccharide component. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1600–1607. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1600-1607.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pejcic-Karapetrovic B, et al. Pregnancy impairs the innate immune resistance to Salmonella typhimurium leading to rapid fatal infection. J Immunol. 2007;179:6088–6096. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.6088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wong CE, Sad S, Coombes BK. Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium exploits Toll-like receptor signaling during the host-pathogen interaction. Infect Immun. 2009;77:4750–4760. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00545-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khan R, et al. Refinement of the genetics of the host response to Salmonella infection in MOLF/Ei: regulation of type 1 IFN and TRP3 pathways by Ity2. Genes Immun. 2012;13:175–183. doi: 10.1038/gene.2011.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gordon MA, et al. Invasive non-typhoid salmonellae establish systemic intracellular infection in HIV-infected adults: an emerging disease pathogenesis. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:953–962. doi: 10.1086/651080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.