Abstract

Objective

Total laryngectomy (TL) can be offered for management of chronic aspiration, radionecrosis, and/or airway compromise after head and neck cancer (HNC) treatment. The objective was to evaluate functional outcomes after TL in disease-free HNC survivors.

Design

Retrospective case series with chart review.

Setting

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Patients

Twenty-three disease-free HNC survivors who underwent TL for laryngopharyngeal dysfunction.

Intervention

TL ± pharyngectomy.

Main Outcome Measures

Post-TL swallowing-related (diet, gastrostomy dependence, and pneumonia rates) and communication outcomes.

Results

All patients who underwent TL for dysfunction were previously treated with radiotherapy (12/23, 52%) or chemoradiotherapy (11/23, 48%). Preoperative complications included aspiration (22/23, 96%), pneumonia (16/23, 70%), tracheostomy (9/23, 39%), and stricture (7/23, 30%); 17 (74%) required enteral/parenteral nutrition and 13/23 (57%) were nothing per oral (NPO). Rates of pneumonia, NPO status, and feeding tube dependence significantly decreased after TL (p<0.001). At last follow-up after TL, all patients tolerated oral intake, but 4 (17%) required supplemental enteral nutrition. Continued smoking after radiotherapy and a preoperative history of recurrent pneumonia were significantly (p<0.05) associated with final tube dependence and/or diet level. Sixteen patients (70%) underwent tracheoesophageal (TE) puncture and 57% (13/23) communicated using TE voice after TL.

Conclusion

Salvage TL may improve health status by significantly decreasing the rate of pneumonia and improve quality of life by restoring oral intake in patients with refractory laryngopharyngeal dysfunction after HNC treatment. TE voice restoration may enhance functional outcomes in select patients treated with elective TL for dysfunction.

Keywords: Laryngectomy, Radiotherapy, Laryngopharyngeal dysfunction

INTRODUCTION

Organ preservation regimens have become increasingly popular in the management of head and neck cancer (HNC) in the last two decades.1 Conservation surgery and radiotherapy-based treatments are the principal modalities used in effort to preserve critical upper aerodigestive tract structures and function. While functional preservation is achieved for many individuals, fibrosis and radionecrosis of the larynx and pharynx are recognized as potential late effects that may significantly impact an unfortunate subgroup of HNC survivors.2 Severe laryngopharyngeal dysfunction may result in airway compromise or chronic aspiration that ultimately leads to pneumonia, and often mandates permanent tracheostomy and/or gastrostomy dependence. Failure to preserve laryngopharyngeal function can be a life-threatening complication in HNC survivors that is devastating to patients’ well-being and quality of life.

Salvage total laryngectomy (TL) is an option for surgical management of chronic aspiration, radionecrosis, and/or airway compromise.3–6 Total laryngectomy prevents aspiration by separating the airway from the digestive tract. However, removal of the larynx also results in loss of laryngeal voice and necessitates a permanent tracheostoma for respiration. Previous authors have reported outcomes of elective TL for intractable aspiration in small series of patients with neurogenic dysphagia.3,5,6 Total laryngectomy eliminated aspiration in all 25 cases combined from these prior studies, and all patients were reported to tolerate oral intake post-laryngectomy. Among these studies, a comprehensive retrospective analysis also suggests that quality of life may be enhanced as evidenced by findings of significant improvements in aspiration pneumonia scores, body mass index, laboratory markers of nutritional status and inflammation, and depression scores among patients and family after elective laryngectomy.3 Voice restoration after elective TL was not reported in these prior series, but successful tracheoesophageal (TE) voice restoration has been shown to positively impact quality of life in patients who require total laryngectomy for cancer treatment.7

Although salvage TL is a common surgical procedure offered for definitive management of severe laryngopharyngeal dysfunction in HNC survivors, its use is relatively rare and outcomes remain undocumented in this distinct population. Salvage TL was required for radionecrosis or intractable aspiration in only 1.4% of patients (7/517) randomized to laryngeal preservation regimens for advanced stage squamous carcinoma in the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 91-11 trial,8 and accounted for only 3% to 8% of laryngectomies reported in two published cohort studies.9,10 A review of the literature yields no summary of outcomes after elective TL for dysfunction in disease-free HNC survivors, but there is evidence from a single case-study that swallowing physiology remains impaired despite the fact that aspiration is controlled after TL.4 The intent of the current study was not to confirm the known fact that TL relieves intractable aspiration. Rather, the primary objective of this study was to comprehensively describe rehabilitative outcomes (swallowing and communication) of elective TL that are missing in published literature. We also examined, for the first time, the feasibility of TE voice restoration after elective TL in disease-free HNC survivors who likely have elevated risk of complications and susceptibility to aspiration compromise.

METHODS

This 6-year retrospective study included all patients previously treated for HNC who underwent total laryngectomy with or without pharyngectomy between 01/2003 and 12/2008 at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Disease-free HNC survivors who underwent laryngectomy for laryngopharyngeal dysfunction due to prior cancer treatment, surgical and/or nonsurgical, were included in this case series. Absence of recurrent disease was confirmed by surgical pathology. Laryngopharyngeal dysfunction included chondroradionecrosis, dysphagia, and/or airway compromise. Demographic information, treatment history, preoperative functional status, operative variables, and complications were collected by review of the electronic medical record. Postoperative communication, swallowing, and nutritional outcomes were recorded at last disease-free follow-up. Functional data were captured in a standardized process in institutional databases at the time of modified barium swallow (MBS) studies and, among those who received tracheoesophageal puncture (TEP), at the time of TEP clinic visits. Tracheoesophageal (TE) voice fluency was graded based on previously published standards; fluent TE speech was defined by the ability to produce 10 to 15 syllables per breath and sustain vowel production (/a/) for a minimum of 10 seconds.11 Leakage complications related to TE voice restoration were included in this analysis because they result in aspiration and may increase the risk of pneumonia after elective TL. Leakage/aspiration complications related to TEP included: 1) enlarged TEP, defined by leakage around the prosthesis unresponsive to standard prosthetic management,9 and/or 2) poor prosthetic life, defined by 2 or more consecutive prostheses lasting 4 weeks or less due to leakage through the prosthesis. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. A waiver of informed consent was obtained.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize sample characteristics, preoperative status, complications, and postoperative outcomes. Statistical associations between categorical variables were analyzed using Pearson’s chi-square test. Statistical significance was considered α-level 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the STATA data analysis statistical software, version 10.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics and Indications for Elective TL

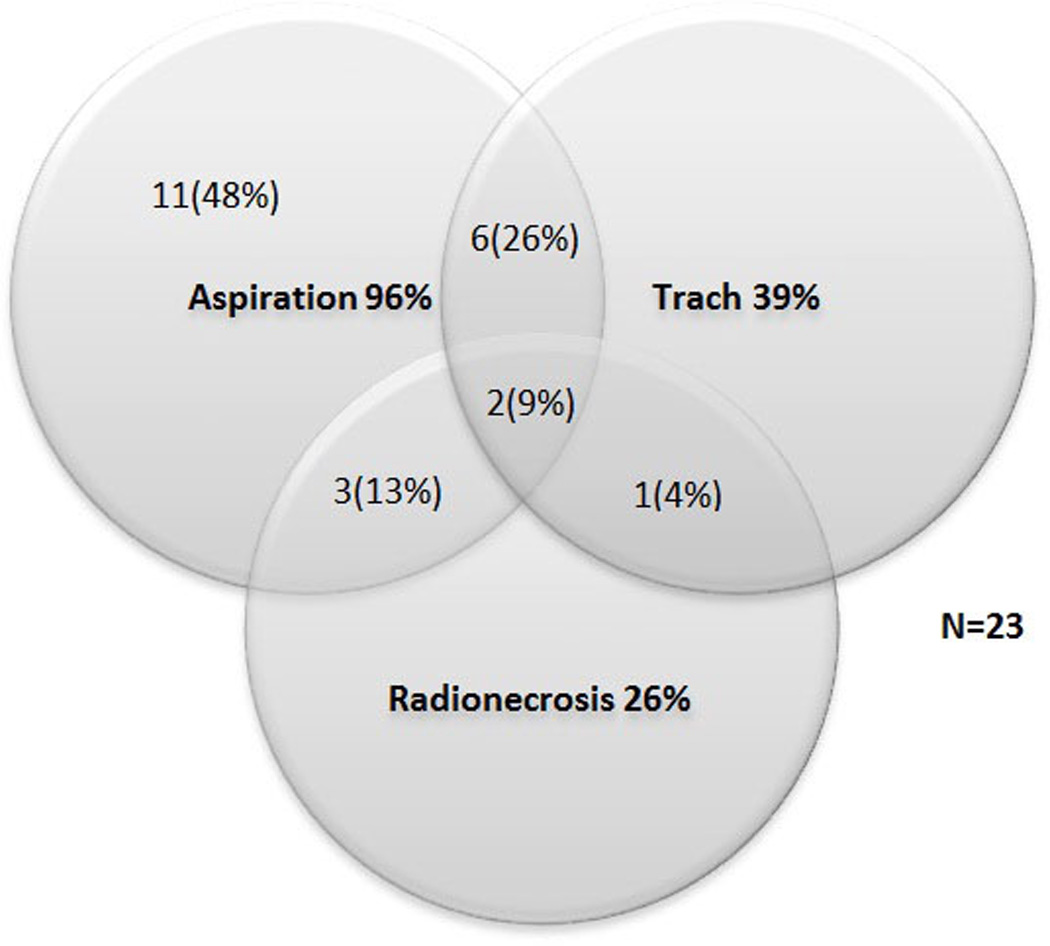

Twenty-three of 376 (6%) total laryngectomies were performed due to laryngopharyngeal dysfunction in disease-free HNC survivors during the 6-year study period. Table I describes sample characteristics. All patients were previously treated with radiotherapy (12/23, 52%) or chemoradiotherapy (11/23, 48%), 21 (91%) as definitive treatment and 2 (9%) in the postoperative setting after a thyroidectomy and radical neck dissection. None had received definitive intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT). Four patients also had a history of conservation surgery before elective TL, including partial laryngectomy (2/23), base of tongue resection (1/23), and wide local excision of the pharyngeal wall with postoperative re-irradiation and concurrent chemotherapy (1/23). Most (21/23, 91%) were former or current smokers; 7 (30%) continued to smoke after radiotherapy or chemoradiation. Five patients were hospitalized at the time of TL. Complications and functional problems prior to elective TL are summarized in Table II. Aspiration was the most common functional problem prior to elective TL (22/23, 96%) followed by dependence on enteral/parenteral nutrition (17/23, 74%) and pneumonia (16/23, 70%). Six patients (26%) had chrondroradionecrosis. The interactions among indications for elective TL are illustrated in Figure I. Elective TL was performed a median of 2.2 years (range: 0.1–23.3) after the last cancer treatment.

Table I.

Sample Characteristics

| No. (%) Pts | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 20 (87.0%) |

| Female | 3 (13.0%) |

| Age | |

| Median (range) | 61 (40–76) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 18 (78.3%) |

| Hispanic | 3 (13.0%) |

| Black | 2 (8.7%) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never | 2 (8.7%) |

| Former | 16 (69.6%) |

| Current | 5 (21.7%) |

| Smoke after radiotherapy/chemoradiotherapy | |

| No | 16 (69.6%) |

| Yes | 7 (30.4%) |

| Site of primary HNC | |

| Larynx | 9 (39.1%) |

| Oropharynx | 7 (30.4%) |

| Hypopharynx | 3 (13.0%) |

| Unknown primary | 3 (13.0%) |

| Thyroid | 1 (4.4%) |

| Prior HNC treatment | |

| Radiotherapy | 8 (34.8%) |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 9 (39.1%) |

| Surgery → RT/CRT | 2 (9.0%) |

| RT/CRT → salvage conservation surgery | 4 (17.4%) |

| Location of radiotherapy | |

| MDACC | 11 (47.8%) |

| Outside facility | 12 (52.1%) |

| Extent surgery (for dysfunction) | |

| TL | 14 (60.9%) |

| TL + partial pharyngectomy | 6 (26.1%) |

| TLP | 3 (13.0%) |

| Tracheoesophageal puncture | |

| None | 7 (30.4%) |

| Primary | 8 (34.8%) |

| Secondary | 8 (34.8%) |

| Time post last HNC treatment | |

| Median yrs (range) | 2 (0.1–23) |

| >5 yrs posttreatment | 7 (30.4%) |

| >10 yrs posttreatment | 5 (21.7%) |

| Total sample | 23 |

Abbreviations: HNC, head and neck cancer, RT, radiotherapy, CRT, chemoradiotherapy, MDACC, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, TL, total laryngectomy, TLP, total laryngopharyngectomy

Table II.

Indications for Total Laryngectomy: Complications and Adverse Functional Effects

| No. (%) | |

|---|---|

| Dysphagia | |

| Aspiration | 22 (95.7%) |

| Stricture | 7 (30.4%) |

| Enteral/parenteral nutrition | 17 (73.9%) |

| NPO | 13 (56.5%) |

| Airway/tracheostomy | 9 (39.1%) |

| Chondroradionecrosis | 6 (26.1%) |

| Pneumonia | |

| None | 7 (30.4%) |

| Single episode | 4 (17.4%) |

| Recurrent/chronic | 12 (52.2%) |

Abbreviations: NPO, nil per os

Figure I.

Interactions among Indications for Total Laryngectomy

Laryngectomy Procedure

Nine (39%) patients required pharyngectomy (6 partial, 3 total) with pharyngeal reconstruction. Circumferential reconstruction included 1 jejunal interposition, 1 circumferential anterolateral thigh flap, and 1 tubed pectoralis major myocutaneous flap. Partial reconstruction included 5 anterolateral thigh free flaps and 1 radial forearm free flap. Three patients had pharyngocutaneous fistulas, 2 of whom required surgical repair. Median length of hospitalization was 7 days (range: 4–40).

Swallowing-related Outcomes after Elective TL

At last disease-free follow-up after TL (median: 28.4 months, range: 1.1–81.9), all patients tolerated some level of oral intake. The majority 17/23 (74%) ate a regular or soft diet. Four (17%) required enteral nutrition to supplement oral intake, 2 due to persistent radiation-related dysphagia, 1 due to a diagnosis of metastatic colon cancer, and 1 remained tube-dependent at time of death 2.5 months post-TL. Those who continued to smoke after radiotherapy were more likely to remain feeding tube dependent at last follow-up (p=0.026). A preoperative history of recurrent pneumonia was significantly associated with chronic feeding tube dependence (p=0.04) and final diet (p=0.01). Extent of surgery (partial or total pharyngectomy) and flap reconstruction were not significantly associated with feeding tube dependence or post-TL diet level. Post-laryngectomy MBS studies revealed narrowing or dysmotility of the pharyngoesophagus in 47% (11/23) of patients. Swallowing-related outcomes before and after salvage TL are compared in Table III. Rates of pneumonia, NPO status, and dependence on enteral/parental nutrition significantly decreased after TL (p<0.001).

Table III.

Comparison of Swallowing-Related Outcomes before and after Total Laryngectomy

| Before TL | After TL | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia | 16 (69.6%) | 3 (13.0%) | <0.001 |

| NPO | 13 (56.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 |

| Enteral/parental nutrition | 17 (73.9%) | 4 (17.4%) | <0.001 |

No. (%) of patients

Abbreviations: NPO, nil per os

Alaryngeal Voice Restoration after Elective TL

Sixteen (70%) patients received tracheoesophageal puncture (TEP); 8 as a primary and 8 as a secondary procedure. Ninety-four percent (15/16) of patients who underwent TEP acquired fluent TE speech. Overall, 14/16 (88%) who received TEP achieved functional TE voice and communicated primarily by TE voice at last follow-up. Among the 7 who did not receive a TEP: 2 patients declined TEP due to preference for less complex methods of voice restoration, 2 did not receive TEP due to unstable medical status related to comorbidities or second primary malignancy, and 3 did not receive TEP after unsatisfactory TE voicing on intraesophageal insufflation testing. Only 2 of these 7 patients who did not receive TEP had received free flap reconstruction (1 partial, 1 total). At last follow-up was, 57% (13/23) communicated primarily by TEP, 26% (6/23) by electrolarynx, 17% (4/23) by writing/gestures.

Eight of 16 patients (50%) experienced leakage complications after TEP. Two patients experienced leakage around the prosthesis requiring management with custom prostheses, and an additional six experienced recurrent, early leakage through the prosthesis. Premature leakage through the prosthesis was managed by frequent exchange of the prosthesis or placement of an increased-resistance prosthesis. None experienced severe enlargement of the TEP.

Associations between Swallowing-related and Communication Outcomes

Communication and swallowing outcomes after TL were significantly associated (p = 0.022); 92.3% (12/13) of TE speakers resumed a regular or soft p.o. diet compared with only 50% (5/10) of patients who communicated via other modalities. Likewise, only 7.7% (1/13) of TE speakers remained feeding tube dependent at last follow-up compared with 30% (3/10) of patients who communicated via other modalities (p = 0.162). Leakage complications after TEP were not significantly associated with rates of post-laryngectomy pneumonia (p = 0.955) or post-laryngectomy swallowing dysfunction (p = 0.469).

DISCUSSION

Organ-sparing treatments have become increasingly popular for management of head and neck cancers in the last two decades with the goal of preserving critical aerodigestive tract structures and function.1 Unfortunately, individuals treated with radiation-based organ preservation regimens are at risk for laryngopharyngeal dysfunction that may ultimately result in potentially life-threatening chronic aspiration or airway compromise after cancer therapy. Rates of chronic aspiration in HNC survivors vary in the literature from 23% to 44%,12,13 and laryngeal chondroradionecrosis has been reported in 1% to 5% of HNC patients previously treated with radiation therapy or chemoradiation.14,15 Although a variety of toxicities were documented prior to laryngectomy, chronic aspiration was the most common indication for elective TL in disease-free HNC survivors in this study. In fact, 96% of patients had documented aspiration prior to elective TL and nearly 75% required enteral or parental nutrition. For this reason, swallowing-related outcomes are highly relevant and often become a focus of preoperative discussions with patients and their families. The results of this study provide, for the first time, published functional outcomes to inform preoperative discussions in patients considering elective TL for dysfunction after HNC treatment.

Total laryngectomy prevents aspiration by separation of the airway from the digestive tract. As such, it was not unexpected that all patients in this study were able to resume oral intake after aspiration was controlled by laryngectomy, and that rates of pneumonia and gastrostomy dependence were significantly lower after elective TL. Aspiration is, however, only one component of swallowing dysfunction in HNC survivors. Numerous authors have documented decreased swallowing efficiency related to physiologic impairments in the swallowing mechanism after HNC treatment. Commonly cited impairments include, among others, decreased tongue base retraction and reduced pharyngeal contraction related to fibrosis or denervation of the swallowing musculature.16,17 Similarly, published data suggest diminished tongue base to pharyngeal wall pressures, increased bolus transit times through the pharynx and cervical esophagus, and higher percentages of oral and pharyngeal residue after elective TL relative to normal function.4 Our findings of persistent post-laryngectomy stenosis or neopharyngeal dysmotility in almost half of patients support those of previous authors to conclude that, despite control of aspiration, TL does not normalize swallowing physiology after HNC treatment. Nonetheless, satisfactory swallowing outcomes were observed in the majority of HNC survivors with 83% achieving feeding tube removal and 74% maintaining nutrition orally on a soft or regular oral diet after TL without enteral support. Only 2 patients who were followed more than 6 months postoperatively remained tube dependent after TL compared with 17 before TL.

Realistic expectations of post-laryngectomy swallowing function must be established during preoperative counseling accounting for baseline swallowing status, extent of fibrosis and neuropathy, as well as the planned surgical resection and reconstructive procedures. A thorough cranial nerve examination and instrumental swallowing assessment are critical to inform these preoperative discussions. In addition to preoperative functional considerations, we identified two clinical variables that may help to predict less favorable swallowing outcomes after elective TL. First, continued smoking after radiotherapy or chemoradiation was associated with significantly higher rates of gastrostomy dependence after TL. This finding is supported by previous authors who have documented the adverse effect of tobacco smoke on wound healing and an increased incidence of high-grade late toxicities in HNC patients who smoke during radiotherapy.18,19 Second, our analysis found that a history of recurrent pneumonia prior to TL was significantly associated with both post-laryngectomy diet levels and feeding tube status. In fact, all patients who remained on a restricted oral diet (pureed/liquid) or who were gastrostomy dependent after TL had a history of recurrent or chronic pneumonia preoperatively. Preoperative comorbidity scores suggested a tendency for more impaired performance status in patients who had experienced recurrent pneumonias, and we speculate that these individuals might also have had more severe pre-laryngectomy dysphagia than those who did not have recurrent pnuemonias. Regardless, attention to baseline functioning, smoking status, and pneumonia history in preoperative consultations is encouraged.

Successful TE voice restoration was achieved in almost 60% of HNC survivors who underwent elective TL for dysfunction. Rates of successful TE voice restoration after elective TL are unique findings of this study, as TE voice outcomes have not been reported in previously published series of TL for intractable aspiration related to neurogenic dysphagia.3,5,6 Although our findings demonstrate the feasibility of TEP after elective TL, the decision to pursue TE voice restoration should not be taken lightly because TEP reintroduces the risk of aspiration by re-establishing a connection between the esophagus and airway. Indeed, post-laryngectomy aspiration occurred as the result of prosthetic leakage complications (i.e., leakage around the prosthesis, or premature leakage through the prosthesis) in half of patients who underwent TEP in this analysis. In many cases, problems associated with leakage through or around a TE prosthesis can be effectively managed with prosthetic modification such as placing an enlarged-flange prosthesis or an increased-resistance valve.20,21 The benefit of conservative techniques such as TEP-site injection for management of leakage around the prosthesis have also been reported.22,23 Fortunately, those who experienced TEP complications in this study did not have significantly increased rates of pneumonia after TL due to effective methods of prosthetic management. Ultimately, successful TE voice restoration relies on appropriate patient selection and access to clinicians with expertise in postlaryngectomy rehabilitation.

The results of this study emphasize the close relationship between communication and swallowing outcomes after laryngectomy. The pharyngoesophagus is shared as a common tube for swallowing and TE phonation postoperatively. As such, individuals with significant dysphagia related to neuromuscular dysfunction or anatomical aberrations after TL may achieve suboptimal results with TE voice restoration. For example, significant postoperative stricture is often associated with a tight or strained TE voice quality and elevated intraesophageal pressures that may predispose to frequent leakage through or around the voice prosthesis. Alternatively, a hyptotonic or amotile neopharynx after reconstruction may contribute to slow bolus transit, but also a breathy or wet phonatory quality. Correlations between successful TE voice restoration and favorable swallowing outcomes in this study might also reflect psychosocial differences among patients such as motivation to participate in postoperative rehabilitation. In addition to intraesophageal insufflation testing and clinical examination,24 postlaryngectomy swallowing outcomes (diet levels, gastrostomy dependence, and MBS results) and psychosocial functioning are important factors that are used to inform decisions about candidacy for TE voice restoration.

CONCLUSION

These data suggest favorable swallowing outcomes for the majority of HNC survivors who receive elective TL for severe, refractory laryngopharyngeal dysfunction after cancer therapy. Our findings indicate that elective TL not only prevents aspiration, but might positively impact health status and quality of life as evidenced by statistically significant improvements in gastrostomy dependence and pneumonia rates postoperatively. However, TL should not be expected to normalize swallowing function and realistic expectations should be established accounting for baseline functional status. In addition to pre-laryngectomy aerodigestive tract functioning, continued smoking after radiotherapy and recurrent pneumonia may help to predict unfavorable swallowing outcomes. Finally, we demonstrate the feasibility of TE voice restoration in select patients who receive elective TL for dysfunction. TE voice restoration may serve to further enhance functional outcomes and quality of life in this select population. Despite limitations of a retrospective observational study, this study represents the first attempt to summarize functional outcomes of a rare subpopulation in a relatively large, unselected cohort. Collectively, these outcomes can be used to assist with evidenced-based decision-making and preoperative counseling for HNC survivors considering elective TL for laryngopharyngeal dysfunction.

Acknowledgement

Dr. Hutcheson acknowledges funding from the UT Health Innovation for Cancer Prevention Research Fellowship, The University of Texas School of Public Health – Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) grant #RP101503. The authors also acknowledge the invaluable support of Janet Hampton and Asher Lisec-Smith.

Footnotes

Disclosures: none

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the CPRIT.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cooper JS, Porter K, Mallin K, et al. National Cancer Database report on cancer of the head and neck: 10-year update. Head Neck. 2009 Jun;31(6):748–758. doi: 10.1002/hed.21022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Platteaux N, Dirix P, Dejaeger E, Nuyts S. Dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients treated with chemoradiotherapy. Dysphagia. Jun;25(2):139–152. doi: 10.1007/s00455-009-9247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takano Y, Suga M, Sakamoto O, Sato K, Samejima Y, Ando M. Satisfaction of patients treated surgically for intractable aspiration. Chest. 1999 Nov;116(5):1251–1256. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.5.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lazarus C, Logemann JA, Shi G, Kahrilas P, Pelzer H, Kleinjan K. Does laryngectomy improve swallowing after chemoradiotherapy? A case study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002 Jan;128(1):54–57. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garvey CM, Boylan KB, Salassa JR, Kennelly KD. Total laryngectomy in patients with advanced bulbar symptoms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009 Oct-Dec;10(5–6):470–475. doi: 10.3109/17482960802578373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomita T, Tanaka K, Shinden S, Ogawa K. Tracheoesophageal diversion versus total laryngectomy for intractable aspiration. J Laryngol Otol. 2004 Jan;118(1):15–18. doi: 10.1258/002221504322731565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xi S. Effectiveness of voice rehabilitation on vocalisation in postlaryngectomy patients: a systematic review. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2010 Dec;8(4):256–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2010.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weber RS, Berkey BA, Forastiere A, et al. Outcome of salvage total laryngectomy following organ preservation therapy: the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group trial 91–11. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003 Jan;129(1):44–49. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutcheson KA, Lewin JS, Risser J, Sturgis EM. Multivariable analysis of risk factors for enlarged tracheoesophageal puncture after total laryngectomy. Head Neck. 2011 doi: 10.1002/hed.21777. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Op de Coul BM, Hilgers FJ, Balm AJ, et al. A decade of postlaryngectomy vocal rehabilitation in 318 patients: a single Institution's experience with consistent application of provox indwelling voice prostheses. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000 Nov;126(11):1320–1328. doi: 10.1001/archotol.126.11.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewin JS, Bishop-Leone JK, Forman AD, Diaz EM., Jr. Further experience with Botox injection for tracheoesophageal speech failure. Head Neck. 2001 Jun;23(6):456–460. doi: 10.1002/hed.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell BH, Spinelli K, Marbella AM, Myers KB, Kuhn JC, Layde PM. Aspiration, weight loss, and quality of life in head and neck cancer survivors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004 Sep;130(9):1100–1103. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.9.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutten H, Pop LA, Janssens GO, et al. Long-Term Outcome and Morbidity After Treatment with Accelerated Radiotherapy and Weekly Cisplatin for Locally Advanced Head-and-Neck Cancer: Results of a Multidisciplinary Late Morbidity Clinic. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011 Nov 20; doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Narozny W, Sicko Z, Kot J, Stankiewicz C, Przewozny T, Kuczkowski J. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the treatment of complications of irradiation in head and neck area. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2005 Mar-Apr;32(2):103–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zbaren P, Caversaccio M, Thoeny HC, Nuyens M, Curschmann J, Stauffer E. Radionecrosis or tumor recurrence after radiation of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal carcinomas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006 Dec;135(6):838–843. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.06.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutcheson KA, Barringer DA, Rosenthal DI, May AH, Roberts DB, Lewin JS. Swallowing outcomes after radiotherapy for laryngeal carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008 Feb;134(2):178–183. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2007.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisbruch A, Lyden T, Bradford CR, et al. Objective assessment of swallowing dysfunction and aspiration after radiation concurrent with chemotherapy for head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002 May 1;53(1):23–28. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02712-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marin VP, Pytynia KB, Langstein HN, Dahlstrom KR, Wei Q, Sturgis EM. Serum cotinine concentration and wound complications in head and neck reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Feb;121(2):451–457. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000297833.53794.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen AM, Chen LM, Vaughan A, et al. Tobacco smoking during radiation therapy for head-and-neck cancer is associated with unfavorable outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011 Feb 1;79(2):414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hutcheson KA, Lewin JS, Sturgis EM, Risser J. Outcomes and Adverse Events of Enlarged Tracheoesophageal Puncture after Total Laryngectomy. Laryngoscope. 2011 doi: 10.1002/lary.21807. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewin JS, Hutcheson KA. Head and neck cancer a multidisciplinary approach. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. General principlies of rehabilitation of speech, voice, and swallowing function after treatment of head and neck cancer; pp. 168–177. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shuaib SW, Hutcheson KA, Knott JK, Lewin JS, Kupferman ME. Minimally-invasive approach for the management of the leaking tracheoesophageal puncture. Laryngoscope. doi: 10.1002/lary.22401. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hutcheson KA, Lewin JS, Sturgis EM, Kapadia A, Risser J. Enlarged tracheoesophageal puncture after total laryngectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2011 Jan;33(1):20–30. doi: 10.1002/hed.21399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewin JS, Baugh RF, Baker SR. An objective method for prediction of tracheoesophageal speech production. J Speech Hear Disord. 1987 Aug;52(3):212–217. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5203.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]