Summary

Ubiquitination of transcription activators has been reported to regulate transcription via both proteolytic and non-proteolytic routes, yet the function of the ubiquitin (Ub) signal in the non-proteolytic process is poorly understood. By use of the heterologous transcription activator LexA-VP16 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, we show that mono-ubiquitin fusion of the activator prevents stable interactions between the activator and DNA, leading to transcription inhibition without activator degradation. We identify the AAA+ ATPase Cdc48 and its cofactors as the Ub receptor responsible for extracting the mono-ubiquitinated activator from DNA. Our results suggest that deubiquitination of the activator is critical for transcription activation. These findings with LexA-VP16 extend in both yeast and mammalian cells to native transcription activators Met4 and R-Smads, respectively, that are known to be oligo-ubiquitinated. The results reveal a previously unidentified mode of transcription regulation and illustrate a role for Ub and Cdc48 in gene expression that is independent of proteolysis.

Introduction

Eukaryotic gene expression is a crucial process that must be controlled in a time and locus-specific manner during cell growth and development. Transcription activators play a key role in gene expression by coordinating the assembly of complex machineries including RNA polymerase II (RNAPII), general transcription factors, and various co-activators that modify or remodel chromatin. Not surprisingly, the abundance, localization, and activity of transcription activators all are subject to tight control. This is achieved in part through the action of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) (Geng et al., 2012; Yao and Ndoja, 2012; and references therein). One way in which the UPS regulates transcription activators is by controlling their abundance. A large number of activators contain transcription activation domains that overlap with degrons, which signal poly-ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of the activator. This and other observations suggest that destruction of the activator is linked to its ability to activate transcription. Another way the UPS regulates transcription activators is by controling their cellular localization. Depending on the activator, mono or oligo-ubiquitination can promote either nuclear localization (van der Horst et al., 2006) or nuclear export (Li et al., 2003). There also is evidence that mono or oligo-ubiquitination and the 19S Regulatory Particle (RP) of the proteasome have direct roles in transcription that are independent of proteolysis. In one case, mono-Ub was reported to stabilize transcription factor-DNA interactions (Archer et al., 2008; Ferdous et al., 2007). A consensus has yet to emerge on how mono-ubiquitination of transcription activators affects their activities.

For the yeast transcription repressor α2, poly-ubiquitination leads to removal of α2 from chromatin with subsequent degradation by the proteasome (Wilcox and Laney, 2009). Removal of α2 is mediated by the AAA+ ATPase Cdc48 (known as p97 or valosin-containing protein (VCP) in mammals). Although Cdc48 has been implicated as a Ub-selective chaperone in other processes (Jentsch and Rumpf, 2007), this was the first indication that it regulates chromatin-bound proteins. Subsequently, multiple groups have demonstrated that proteasomal degradation of chromatin-bound substrates often requires extraction by Cdc48; examples include stalled RNAPII (Verma et al., 2011), proteins involved in DNA repair (Acs et al., 2011; Meerang et al., 2011), and replication licensing factor Cdt1(Raman et al., 2011). In a related observation, at the end of mitosis Cdc48 was shown to remove Aurora B kinase from chromatin independently of proteolysis (Ramadan et al., 2007). In all of these cases, poly-ubiquitination of the substrate appeared to be a prerequisite for Cdc48 action.

In order to understand the underlying mechanism of how ubiquitination of activators regulates transcription, we have used a model system established previously by Salghetti et al. They demonstrated that in Saccharomyces cerevisiae the heterologous transcription activator LexA-VP16 is poly-ubiquitinated and rapidly degraded, and that this process is coupled to transcription activation (Salghetti et al., 2001). Here we report that, in contrast, mono-Ub fused to LexA-VP16 inhibits transcription by preventing stable interactions between the activator and DNA. Cdc48 and its cofactors inhibit transcription most likely by extracting LexA-VP16 from DNA in a Ub-dependent manner and without subsequent proteolysis. Surprisingly, fusion with a single Ub is sufficient to recruit Cdc48 to LexA-VP16 and to prevent transcription. We show that this mode of regulation by Cdc48 applies in yeast and mammalian cells to native transcription activators that are known to be oligo-ubiquitinated but not degraded.

Results

Transcription activation by the Ub-LexA-VP16 fusion requires its deubiquitination

LexA-VP16 (LV) is a potent transcription activator composed of the bacterial LexA DNA binding domain and the activation domain from Herpes Simplex Virus protein VP16. LV in yeast is poly-ubiquitinated by Met30, an SCF E3 Ub ligase, and rapidly degraded by the proteasome (Salghetti et al., 2001). This Ub-dependent degradation of LV is coupled to transcription activation. However, by fusing mono-Ub to the N-terminus of LV, Salghetti et al. found that Ub-LV can activate transcription independently of Met30. It is well known that eukaryotic Ub genes encode precursor forms of Ub that are co-translationally processed by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) (Ozkaynak et al., 1984). The Ub C-terminal glycine (G76) is crucial for this processing as well as for subsequent conjugation and deconjugation. To produce stable Ub-fusion proteins in vivo, Ub G76 often is replaced with a larger amino acid in order to resist cleavage by DUBs. Fortuitously, we found that the activation potency of Ub-LV depends on the amino acid introduced at the Ub-76 position. When the C-terminus of Ub in Ub-LV was mutated to alanine (Ub(A76)-LV), Ub-LV activates transcription, in agreement with the report by Salghetti et al. However, when it was changed to valine, Ub(V76)-LV failed to activate transcription in either the presence or absence of Met30 (Figure 1A).

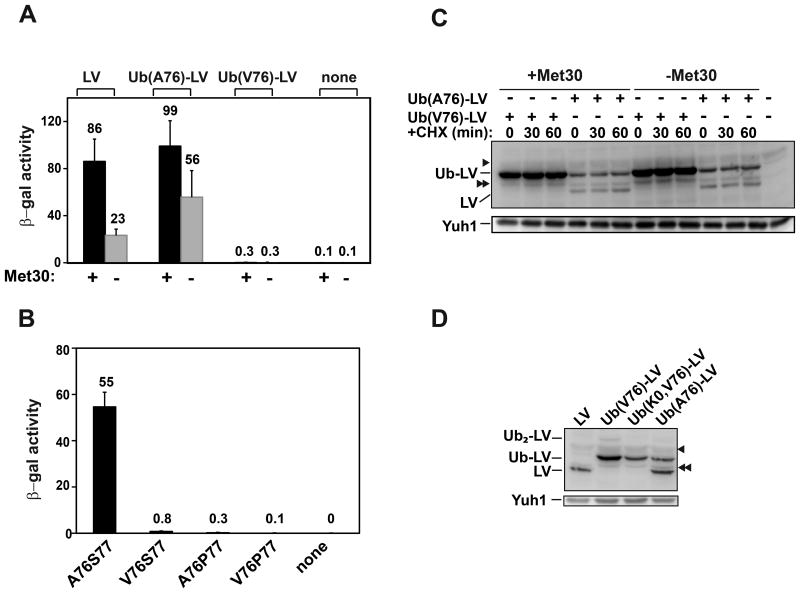

Figure 1. Deubiquitination of the Ub-LV fusion is needed for transcription activation.

(A) A LacZ reporter gene under the control of a 4xLexA operator and minimal GAL1 promoter was integrated into yeast strains with and without endogenous MET30 (YTY358 and YTY224). The strains were transformed with an empty vector (none) or a CEN plasmid expressing LV or Ub-LV fusions from the CYC1 promoter, and LacZ transcription was measured as β-galactosidase activity. Mean values and standard deviations (error bars) are from three independent experiments.

(B) Ub-protein linker residues (i.e., either Ub-76 or the subsequent residue) affect transcription activation by Ub-LV fusions. Ub-LV fusions with different linker residues were expressed in wild-type yeast with an integrated reporter gene (YTY076); transcription was measured as β-galactosidase activity.

(C) Ub(A76)-LV and Ub(V76)-LV are both long-lived in yeast. Yeast strains in (A) were treated with cycloheximide. At the indicated times, aliquots were taken and whole-cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-LexA and (as a loading control) anti-Yuh1 antibodies. Note the appearance of LV in yeast expressing Ub(A76)-LV but not the yeast with Ub(V76)-LV. The arrowhead denotes a non-specific band; the double-arrowhead denotes a degradative fragment of Ub-LV.

(D) Steady-state levels of LV and Ub-LV activators. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed by as in (C). “K0” denotes the Ub mutant in which all seven lysines were mutated to arginines. Ub2-LV indicates a di-ubiquitinated form of LV observed in yeast expressing Ub(V76)-LV but not Ub(K0,V76)-LV.

To test if deubiquitination efficiency was a determinant of transcriptional output, we mutated Ub G76 or the residue immediately after it. In yeast, when this 77th residue is a proline, deubiquitination is inhibited (Bachmair et al., 1986). Among four Ub-LV fusions with different linker residues, we observed that transcription potency correlated with the predicted deubiquitination efficiency; either V76 or P77 dramatically inhibited transcription (Figure 1B). Accordingly, we observed substantial deubiquitination of Ub(A76)-LV but not Ub(V76)-LV (Figures 1C and 1D). These results strongly suggest that deubiquitination of the activator is required for transcription. Thus, Ub modification of at least some transcription factors is likely to be highly dynamic, as stable ubiquitination can prevent transcription activation.

Ub hydrophobic patch mutations restore transcription activation by Ub(V76)-LV

The difference between Ub(A76)-LV and Ub(V76)-LV in transcription activation was unexpected. A possible explanation was that the fused Ub caused rapid turnover of the activator, thereby limiting its abundance in yeast. We found that, on the contrary, both Ub(A76)-LV and Ub(V76)-LV are stable and that Ub(V76)-LV accumulates to even higher levels (Figures 1C and 1D). Therefore, the Ub moiety in Ub(V76)-LV inhibits transcription in a proteolysis-independent manner. To test if the Ub has a specific effect and does not act simply as a bulky attachment that interferes sterically, we mutated residues within the Ub hydrophobic patch, a commonly-used surface for Ub–protein interactions. L8A, L8W or H68D modifications to this surface each greatly enhanced the Ub(V76)-LV-dependent transcription of LacZ (Figure 2A). Ub(L8A,V76)-LV activated transcription to a level similar to LV alone (Figure S1A). These results suggested that interaction of the Ub hydrophobic patch with one or more endogenous Ub receptors prevents transcription activation. Interestingly, the transcription activation by Ub(L8A,V76)-LV was accompanied by rapid degradation of the fusion protein (Figure S1B); this observation confirms the coupling between activator turnover and transcription that was described previously (Salghetti et al., 2001).

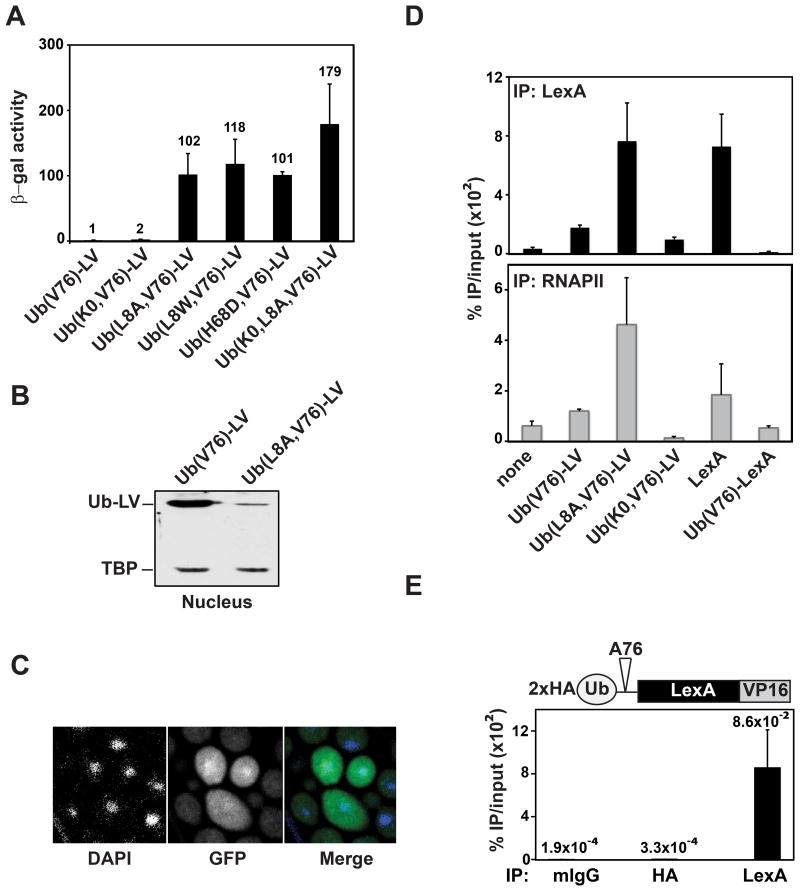

Figure 2. N-terminal fused Ub prevents stable activator-DNA interactions.

(A) Mutations in the Ub hydrophobic patch restore transcription activation by LV. YTY076 yeast were transformed with a plasmid expressing Ub(V76)-LV or the indicated mutated versions from the ACT1 promoter, and transcription of the LacZ reporter was measured as β-galactosidase activity.

(B) Ub(V76)-LV is detected in the nucleus. Nuclei from yeast expressing either Ub(V76)-LV or Ub(L8A, V76)-LV were isolated and nuclear proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

(C) Ub(V76)-LV is localized diffusely both in the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Shown are confocal microscopy images of wild-type yeast expressing Ub(V76)-LV-GFP. Nuclei were stained with DAPI.

(D) The N-terminal fused Ub inhibits promoter occupancy by LexA or LV in vivo. YTY076 was transformed with an empty vector or a plasmid expressing LexA or various LexA fusions. Occupancy of the LexA-operator or the promoter within the reporter gene was evaluated by ChIP analysis with anti-LexA or anti-RNAPII antibody, respectively. Error bars represent standard deviations of mean values from three independent experiments. Note that LexA alone may recruit small amounts of RNAPII non-specifically, but no transcription of LacZ was detected (data not shown).

(E) YTY076 was transformed with a plasmid expressing N-terminal HA-tagged Ub(A76)-LV. ChIP with anti-HA (detecting Ub(A76)-LV) and anti-LexA (detecting Ub(A76)-LV and LV) antibodies revealed that only deubiquitinated LV was stably bound to DNA. Note that anti-HA and anti-LexA ChIP worked similarly well (see Figure 3D).

See also Figure S1.

In addition to changes in the hydrophobic patch, we constructed mutants in which all seven lysines in Ub were mutated to arginines. Because the N-termini of these constructs (methionine followed by aspartate) are likely to be acetylated (Polevoda and Sherman, 2003) and the Ub lacks lysine sites for ubiquitination, Ub(K0,V76)-LV is trapped in a mono-ubiquitinated state (Figure 1D; for the role of Met30 in Ub-LV ubiquitination, see Discussion). As shown in Figure 2A, the Ub(K0) mutations did not affect the transcriptional potency of the Ub(V76)-LV activators; thus, a poly-Ub chain is not required to recruit the putative Ub receptor(s). We observed similar effects when Ub(V76) was fused to a different LexA-activation domain construct, LexA-Gal4AD (Figure S1C), and when the position of Ub(V76) in the fusion protein was C-terminal to LexA or LV (Figure S1D).

To rule out that the fused Ub causes mislocalization of the activator, we fractionated yeast cells and found that even more Ub(V76)-LV was in the nucleus than Ub(L8A,V76)-LV, which activates transcription potently (Figure 2B). We also expressed Ub(V76)-LV as a GFP fusion and found by microscopy that it localized diffusely throughout the yeast cytoplasm and nucleus (Figure 2C). These results show that fusion with Ub(V76) did not cause LV either to be excluded from the nucleus or sequestered in specific cellular compartments.

Ub prevents the LV transcription activator from stably binding to DNA

Next we investigated chromatin localization of Ub-LV by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) (Figure 2D). Although we could clearly detect Ub(V76)-LV at the promoter of the LacZ reporter gene (∼5-fold above background), substantially higher levels were detected with the hydrophobic patch mutant, Ub(L8A,V76)-LV. Consistently, RNAPII levels at the promoter tracked with reporter gene activity. Promoter occupancy by LexA without the activation domain was similar to that of Ub(L8A,V76)-LV. In contrast, the Ub(V76)-LexA fusion was not detected at the promoter. To further demonstrate that the inhibitory effect of the attached Ub moiety is independent of both the activation domain and the transcription machinery recruited by the activation domain, we removed the promoter and ORF regions of the LacZ reporter gene, leaving only the 4xLexA operator site. We obtained similar results in that occupancy at this site by LexA alone was much higher than by Ub(V76)-LexA (Figure S1E).

In the case of Ub(A76)-LV, our results (Figure 1) implicated a role for deubiquitination in transcription activation. We introduced a 2xHA-tag at the N-terminus of the fusion. Anti-HA antibody can detect only the Ub-fusion form of LV, whereas anti-LexA antibody additionally can detect LV alone (Figure S1F). ChIP analysis revealed that only the deubiquitinated form was at the reporter gene (Figure 2E), underscoring the requirement of deubiquitination for activator function.

Cdc48 and its cofactors Ufd1 and Npl4 extract Ub(V76)-LV from DNA

Cdc48 has been shown to extract poly-ubiquitinated proteins from chromatin (Wilcox and Laney, 2009), but there was no clear evidence that mono-ubiquitinated proteins can be extracted similarly. However, mono- or oligo-ubiquitination of a processed form of Spt23 can lead to Cdc48-dependent extraction from its dimerization partner protein embbeded in the ER (Rape et al., 2001). Thus, we considered Cdc48 to be a good candidate responsible for preventing Ub(V76)-LV from stably binding to DNA. In yeast strains with temperature-sensitive proteins expressed from the cdc48-3, ufd1-1, or npl4-2 alleles, transcription activation by Ub(V76)-LV was evident even at the semi-permissive temperature (30 °C) (Figure 3A). We confirmed that at the non-permissive temperature (37 °C) Ub(V76)-LV occupancy at the LacZ promoter is restored in both cdc48-3 and ufd1-1 strains, and that the increased activator occupancy corresponds to increased RNAPII occupancy (Figure 3B). To test whether the ATPase activity of Cdc48 is required to inhibit transcription activation by Ub(V76)-LV, we introduced the cdc48QE mutant which carries a Q-to-E substitution in the D1 ATPase domain (Ye et al., 2003). Overexpression of cdc48QE activated transcription of LacZ as measured by both mRNA levels and β-galactosidase activities (Figure 3C). To prove that Cdc48 inactivation promotes binding of the intact Ub-LV fusion, we took advantage of the N-terminal HA tag in 2xHA-Ub(V76)-LV. At the non-permissive temperature, we observed increased activator occupancy by ChIP analyses with both anti-HA and anti-LexA (Figure 3D); thus, full-length Ub(V76)-LV can bind to the promoter.

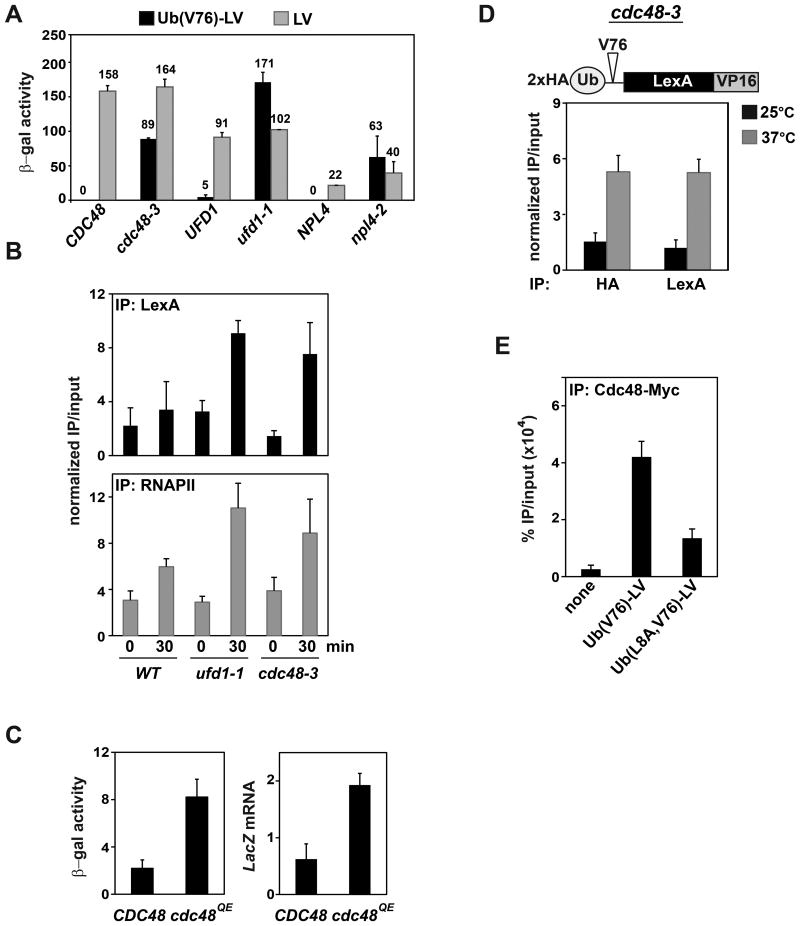

Figure 3. Cdc48 and its cofactors Ufd1 and Npl4 extract Ub(V76)-LV from DNA.

(A) A LacZ reporter gene as in Figure 1 was integrated into yeast expressing temperature-sensitive cdc48-3, ufd1-1, or npl4-2 alleles, or into wild-type isogenic control strains. These were transformed with a CEN plasmid expressing Ub(V76)-LV or LV from the ADH promoter, and transformants were grown at the semi-permissive temperature (30 °C). Transcription of the reporter gene was measured as β-galactosidase activity.

(B) The yeast strains in (A) were grown at 25 °C to log phase before shifting to 37 °C for 30 min. ChIP analysis with anti-LexA antibody showed increased promoter occupancy by Ub(V76)-LV upon inactivation of Ufd1 or Cdc48. Similar increases were observed for RNAPII occupancy. Occupancy at the reporter-gene promoter was normalized to occupancy at the inactive GAL1 locus.

(C) Wild-type Cdc48 or Cdc48QE under the control of a GAL promoter was over-expressed in YTY076 upon addition of galactose. Transcription of the reporter gene was measured as β-galactosidase activity (upper panel) or quantified by qPCR and normalized against that of ACT1 (lower panel).

(D) cdc48-3 yeast were transformed with a plasmid expressing N-terminal HA-tagged Ub(V76)-LV. ChIP analysis with anti-HA and anti-LexA antibodies showed increased promoter occupancy by intact Ub(V76)-LV fusion upon inactivation of Cdc48.

(E) Cdc48 was tagged with C-terminal 13xMyc at the endogenous CDC48 locus. ChIP analysis using anti-Myc antibody showed that Cdc48 is recruited to the reporter gene by Ub(V76)-LV in a Ub-dependent manner.

The results above suggest a scenario in which the segregase activity of Cdc48 and its cofactors prevent Ub(V76)-LV from stably binding to DNA. When we performed ChIP analysis of a tagged form of Cdc48 expressed from the native CDC48 locus, we found that Cdc48 occupancy at the LacZ promoter was significantly higher in cells expressing Ub(V76)-LV than Ub(L8A,V76)-LV (Figure 3E). Thus, Cdc48 most likely acts directly on promoter-bound ubiquitinated activator and strips it from the DNA in a continuous cycle. This could explain why low levels of Ub(V76)-LV are detectable at the promoter (Figure 2D).

Mono-ubiquitination of the Gal4 activator was shown to play important roles in GAL gene transcription, where it was proposed to prevent the 19S RP from stripping Gal4 from the DNA (Archer et al., 2008; Ferdous et al., 2007). To investigate whether the 19S RP has a role in the regulation of Ub(V76)-LV, we measured reporter-gene activities in yeast strains with point mutations in five of the six 19S RP ATPase subunits (Rubin et al., 1998). None of the ATPase mutations affected Ub(V76)-LV-dependent LacZ expression except for rpt5R (Figure S2A). However, the rpt5R mutation did not affect promoter occupancy by either Ub(V76)-LV or RNAPII (Figure S2B). Therefore, the increased β-galactosidase activity we observed is most likely due to indirect effects of the mutation, such as an increased half-life of the β-galactosidase. We conclude that the 19S RP ATPases are unlikely to play a role in the transcriptional regulation afforded by the Ub(V76) fusion to LV.

Mono-Ub is sufficient to prevent transcription activation by LexA-VP16

Due to the dynamic and structurally diverse character of modifications by Ub, the number of Ub molecules attached to native substrates usually is not known. Our experimental system uniquely allowed us to address whether mono-Ub is sufficient to promote Cdc48-dependent remodeling of the substrate. In our previous experiments, the LacZ reporter gene had four upstream LexA operators and therefore could accommodate binding of up to four dimeric Ub-LV molecules. To limit the number of Ub-LV binding sites, we took advantage of a LexA mutant that recognizes an altered operator sequence (Dmitrova et al., 1998). LexA408, which has three amino acid substitutions (P40A, N41S, A42S), was co-expressed with wild-type LV in a yeast strain that contained a LacZ reporter gene constructed with a single hybrid LexA operator recognized only by the LexA408: LexA heterodimer (Figure 4A). As expected for this hybrid operator, LV activated LacZ transcription only when LexA408 also was expressed (Figure 4B). However, surprisingly, transcription was completely abolished when Ub(K0,V76) was fused to LV, but was restored when L8A was introduced as an additional mutation into the Ub moiety. Consistently, Ub(K0,V76)-LV showed low promoter occupancy in comparison with LV (Figure 4C). These results demonstrate that, for LexA, a single mono-Ub is sufficient to prevent stable binding to the operator.

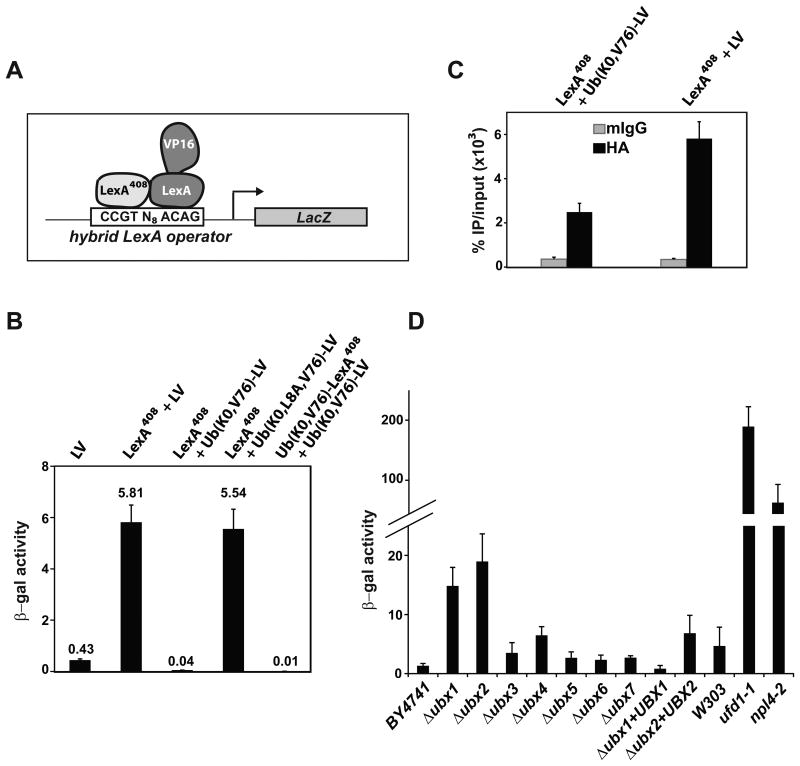

Figure 4. A single Ub is sufficient to inhibit transcription activation by LV.

(A) Schematic of a hybrid LexA operator recognized specifically by the LexA408:LexA heterodimer. LexA408 (bearing P40A, N41S, A42S mutations) binds to the left half of the operator, whereas wild-type LexA binds to the right half (Dmitrova et al., 1998).

(B) A LacZ reporter gene with the hybrid LexA operator was integrated into wild-type yeast. This strain was then transformed with different combinations of plasmids expressing LexA408, LexA-VP16, or their Ub-fusions, from the CYC1 promoter. Transcription of the reporter gene was observed only when LexA408 and LexA-VP16 were expressed together. A single Ub(K0,V76) attached to LV abolished transcription activation as measured by β-galactosidase activity; inhibition by the attached Ub was reversed by L8A mutation at the Ub hydrophobic patch.

(C) ChIP analysis with anti-HA antibodies shows that Ub(K0,V76)-LV has lower promoter occupancy than LV. An HA-tag was inserted between LexA and VP16.

(D) The LacZ reporter gene was integrated into wild-type (BY4741) yeast or strains with one of the seven UBX genes deleted. The LacZ reporter was also integrated into temperature-sensitive ufd1-1, npl4-2 strains and the isogenic wild-type strain (W303). These were transformed with a CEN plasmid expressing Ub(V76)-LV from the ADH promoter, grown at 30 °C to log phase, and LacZ transcription was measured as β-galactosidase activity. Plasmids expressing either Ubx1 or Ubx2 were able to rescue the phenotypes of Δubx1 or Δubx2 strains, respectively.

Cdc48's participation in diverse biological processes is made possible in part by an arsenal of substrate-recruiting adaptor proteins that interact with mono- or poly-Ub. The yeast genome encodes seven non-essential Cdc48 substrate adaptors that contain the Ub-regulatory-X (UBX) domain (Schuberth and Buchberger, 2008). In addition, Ufd1 and Npl4 are essential, highly-conserved Cdc48 adaptors. Using the LacZ reporter-gene assay, we found that only deletion of ubx1 or ubx2 resulted in moderately increased reporter-gene activity (Figure 4D). However, partial inactivation of ufd1 or npl4 by growth at 30 °C had much more pronounced effects. Therefore Ufd1 together with Npl4 are most likely sufficient to direct Cdc48 to DNA-bound Ub(V76)-LV, although we cannot rule out that UBX proteins have roles that were masked by functional redundancy among them.

Cdc48 helps to maintain MET gene repression through oligo-ubiquitinated Met4

The transcription activator Met4 is a master regulator of sulfur metabolism in yeast. In limiting methionine, Met4 activates transcription of a large number of genes (generally termed MET genes) involved in the synthesis of sulfur-containing metabolites. Under non-inducing conditions, Met4 inactivation is required for cell proliferation; this is achieved through ubiquitination by the SCFMet30 E3 Ub ligase (Kaiser et al., 2000). Interestingly, Met4 is modified by a K48-linked oligo-Ub chain, yet escapes proteasome degradation because the chain is shielded by intramolecular association with Ub-binding domains (Ouni et al., 2011 and references therein). However, even without proteolysis, ubiquitination of Met4 is sufficient to prevent MET gene expression. In another layer of regulation, Met4 mediates ubiquitination of cofactors that recruit Met4 to its target genes (Ouni et al., 2010). Ubiquitination of these cofactors, such as Met32, leads to proteasome degradation which further prevents Met4-dependent MET gene activation and Met32-dependent cell cycle arrest.

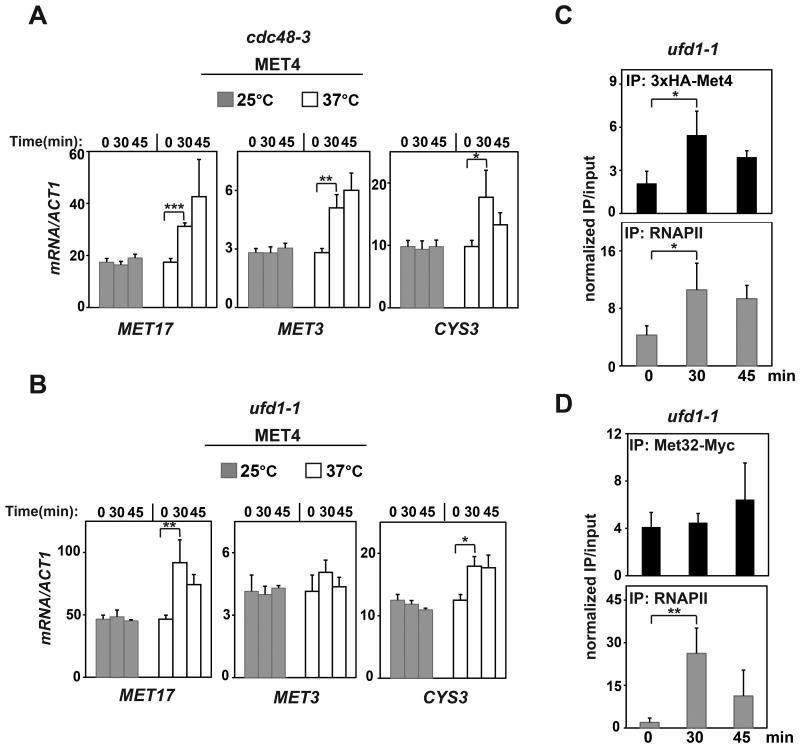

How ubiquitination of Met4 maintains MET genes in a repressed state has been unclear. We hypothesized that Cdc48 may help to keep oligo-ubiquitinated Met4 from binding to target gene promoters under non-inducing conditions. As shown in Figures 5A and 5B, transcription of three such target genes, MET17, MET3 and CYS3, increased upon inactivation of Cdc48 or its cofactor Ufd1, whereas no change was observed in control gene (ACT1) transcription (Figure S3A) or in the presence of wild-type Cdc48 (Figure S3B). Consistently, we also observed increased promoter occupancy by Met4 and RNAPII upon inactivation of Ufd1 (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. Cdc48 and Ufd1 contribute to the maintenance of MET gene repression.

(A) and (B) cdc48-3 and ufd1-1 strains expressing 3xHA-Met4 from the native MET4 promoter were grown at 25 °C in SD-URA medium containing 0.13 mM methionine. At log phase, half of the culture was shifted to 37 °C for the indicated times and MET17, MET3 and CYS3 transcripts were assayed by qRT-PCR. p values were determined by Students' t-test (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001).

(C) The ufd1-1 strain described in (B) was grown at 25 °C to log phase and shifted to 37 °C for the indicated times. Met4 and RNAPII occupancies at the MET17 promoter were monitored by ChIP. ChIP signals were normalized to the silent GAL1 locus.

(D) Met32 was C-terminally tagged with 13xMyc at the endogenous MET32 locus in the ufd1-1 strain. This strain was grown in YPD at 25 °C to log phase and shifted to 37 °C for the indicated times. Met32 occupancy at the MET17 promoter was monitored by ChIP with anti-Myc antibodies. Although RNAPII occupancy and Met4 occupancy increased upon Ufd1 inactivation, Met32 occupancy did not change significantly. By 45 min at 37 °C, occupancy by RNAPII and Met4 had decreased.

See also Figures S3 and S5.

As expected, Met4 ubiquitination was largely unaffected by inactivation of Cdc48 (Figures S3C and S4A). However, Met4-dependent transcription is more complex in that Met4 itself lacks intrinsic DNA-binding activity and is targeted to specific genes through cofactors such as Met32. Although Met32 undergoes proteasome-dependent degradation, we found that Met32 turnover was not affected by inactivation of Cdc48 (Figure S4A). Moreover, upon inactivation of Ufd1, although increased promoter occupancy by Met4 mirrored the recruitment of RNAPII, the kinetics of promoter occupancy by Met32 showed a different pattern (compare Figures 5C and 5D). These results suggest that, to maintain MET gene repression, Cdc48 acts on oligo-ubiquitinated Met4 and not the DNA-binding cofactor Met32.

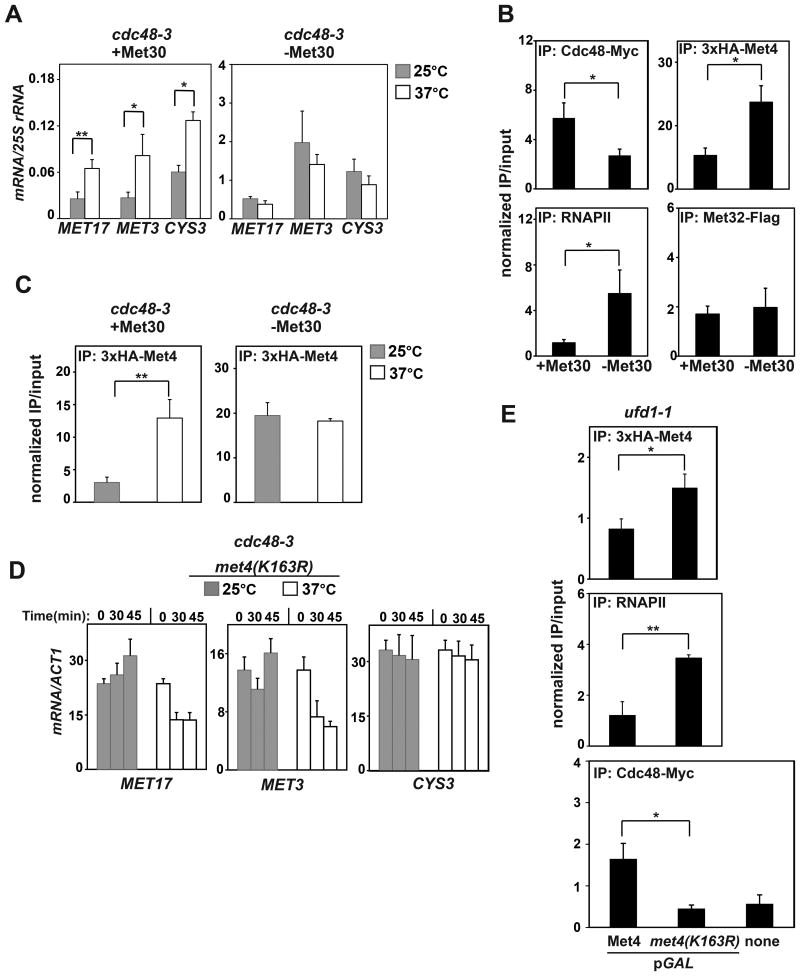

To further demonstrate that the repressive effect of Cdc48 depends on Met4 oligo-ubiquitination, we compared the effects of Cdc48 inactivation with and without Met30. Without Met30, Met4 is not ubiquitinated and activates transcription potently (Kaiser et al., 2000). Our model predicts that Cdc48 has a repressive role only when Met4 is ubiquitinated. Indeed, inactivation of Cdc48 increased MET gene expression only in the presence of Met30 (Figure 6A), and Met4 occupancy at the MET17 promoter was increased by Cdc48 inactivation only in strains expressing Met30 (Figure 6B). Met30 deletion led to marked increases in MET gene transcription (Figure 6A); this was accompanied by higher promoter occupancy by Met4 and RNAPII, but lower occupancy by Cdc48 (Figure 6C). In contrast, the levels of the DNA-binding co-factor, Met32, which was transiently overexpressed from a pGAL promoter, remained constant (Figures 6C and S3D).

Figure 6. Cdc48 represses MET genes through oligo-ubiquitinated Met4.

(A) Cdc48 represses MET genes only in the presence of MET30. cdc48-3Δmet32 and cdc48-3Δmet32Δmet30 strains were grown in SD-URA medium at 25 °C. At log phase, expression of pGAL-Met32-Flag was induced for 2 h followed by shifting half of the culture to 37 °C for 45 min. Expression of endogenous MET17, MET3 and CYS3 genes was assayed by qRT-PCR and normalized to 25S rRNA.

(B) Cdc48 lowers promoter occupancy by Met4 only in the presence of MET30. Strains described in (A) were modified to express 3xHA-Met4 from the native MET4 promoter. These were grown as in (A) and ChIP analysis of Met4 occupancy at the MET17 promoter was performed. ChIP signals were normalized to the RPL11 locus.

(C) For ChIP analysis of MET17 promoter occupancy by Cdc48, Met4, Met32 and RNAPII in the presence and absence of Met30, Δmet32 and Δmet32Δmet30 strains transformed with pGAL-Met32-Flag were modified to either express Cdc48-13xMyc at the endogenous CDC48 locus or 3xHA-Met4 from its native promoter. ChIP signals were normalized to the RPL11 locus.

(D) Cdc48 does not repress MET genes in the presence of Met4(K163R). Expression of MET17, MET3 and CYS3 were analyzed as in Figure 5A except that wild-type Met4 was replaced with Met4(K163R).

(E) 3xHA-tagged Met4 or Met4(K163R) were expressed from the GAL promoter for 40 min and then cells were fixed for ChIP analysis. Whereas Met4(K163R) occupancy was higher than Met4 at the MET17 promoter and correlated with greater recruitment of RNAPII (top and middle panels, respectively), less Cdc48 (Myc-tagged at the endogenous CDC48 locus) was recruited by Met4(K163R).

See also Figures S3 and S4.

Oligo-ubiquitination of Met4 is on a single residue, K163 (Flick et al., 2004). When MET4 was replaced with the met4(K163R) allele, MET genes were de-repressed as previously reported (Figures S3E and S3F). With met4(K163R), inactivation of Cdc48 no longer stimulated MET gene expression (Figure 6D). Unlike wild-type Met4, Met4(K163R) is rapidly degraded, perhaps as a consequence of transcription activation. As a control, we show that inactivation of Cdc48 does not affect the turnover of Met4(K163R) (Figure S4B). Importantly, although Met4(K163R) has higher occupancy at the MET17 promoter and recruits more RNAPII, it fails to recruit Cdc48 (Figure 6E). Taken together, these results strongly support our model in which the oligo-Ub signal on Met4 recruits Cdc48 which in turn represses transcription by removing Met4 from MET gene promoters.

Surprisingly, although deletion of Met30 increased MET17 transcription 20-fold, promoter occupancy by Met4 increased only 3-fold (Figure 6C). In the presence of Met30, inactivation of Ufd1 or Cdc48 led to similar increases in promoter occupancy by Met4 (Figures 5C and 6B), yet MET17 transcription increased only 1.7-fold (Figures 5A and 5B). Because Cdc48 inactivation has only these small effects on steady-state transcript levels, we tested if MET gene repression is affected more profoundly during the transition from limiting to abundant methionine. Figure S5 shows that full repression is achieved within 15 min regardless of whether Cdc48 or Ufd1 is active. However, MET transcripts were maintained at up to 6-fold higher levels when Cdc48 or Ufd1 was inactivated, suggesting that the Cdc48 pathway functions in the maintenance phase of repression. Unlike with MET17 or MET3, we observed significant derepression of SAM1 and SAM2, genes encoding enzymes that synthesize S-adenosylmethione. These data suggest that Met4 target genes are differentially regulated and that transcriptional output is determined by factors in addition to Met4 and RNAPII recruitment, such as elongation factors or chromatin-remodeling activities. Ubiquitination of Met4 may regulate these uncharacterized activities in addition to lowering promoter occupancy through Cdc48.

p97 mediates Ub-dependent inactivation of receptor-activated Smads (R-Smads) independently of proteolysis

In human cells, mono-ubiquitination of R-Smads attenuates TGFβ signaling without promoting R-Smad degradation (Inui et al., 2011; Tang et al., 2011). Inui et al. suggested that ubiquitination sterically interferes with DNA binding, whereas Tang et al. proposed that ubiquitination sterically blocks formation of active Smad3/Smad4 complexes. Although both groups invoked “steric hinderance” models for the repressive effect of mono-ubiquitination, they reported different sites of ubiquitination. Based on our observations with LexA-VP16 and Met4 in yeast, we tested whether the Cdc48 homolog, p97, mediates extraction of ubiquitinated Smad from its interaction with DNA or proteins. We treated MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells with the p97-specific inhibitor DBeQ (Chou et al., 2011) and monitored expression of Smad target genes CTGF and IL-11. Inhibition of p97 increased Smad2/3-mediated transcription both with and without added TGFβ (Figure 7A). Within the 2 h period of treatment, the transcription enhancement by DBeQ alone was similar to that of TGFβ, the native signaling ligand (compare lanes 2 and 3). This suggests that p97 plays a major role in maintaining the Smad target genes in a repressed state. In addition, we found no evidence that inhibition of p97 increased the nuclear pool of Smad2/3 or phospho-Smad2/3 (Figure 7B); rather, a combination of TGFβ and DBeQ treatments slightly decreased nuclear Smad2/3 levels. Therefore, it is unlikely that p97 inhibition affects the signaling process upstream of transcription. By ChIP we found that inhibition of p97 dramatically increased promoter occupancy by Smad2/3 with or without TGFβ treatment (Figure 7C). These data support a model in which p97 helps to repress Smad target genes by preventing DNA binding of ubiquitinated R-Smads. Upon TGFβ signaling, Usp15 deubiquitinates Smad2/3 (Inui et al., 2011), which would lead to p97 dissociation and transcription activation. Interestingly, Smad4, a coactivator of R-smads, similarly has been reported to undergo mono-ubiquitination (Wang et al., 2008). Smad4 mono-ubiquitination disrupts its interaction with Smad2. Therefore, inhibition of p97 by DBeQ also may promote binding of the Smad4 coactivator, which would lead to enhanced transcription of Smad target genes.

Figure 7. p97 inhibits R-Smad-mediated transcription independently of proteolysis.

(A) MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with either 100 pM TGFβ alone or in combination with 10 μM DBeQ, a p97 inhibitor. After 2 h, mRNAs from CTGF and IL11 were analyzed by qRT-PCR and normalized to GAPDH mRNA. Error bars represent standard deviations of mean values from three independent experiments.

(B) Smad2/3 protein levels and cellular localization were not altered by DBeQ treatment. Cells were treated as in (A) and whole-cell extract (WCE), cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for total Smad3 and phospho-Smad2/3 (P-Smad2/3). Tubulin and c-Jun were used as cytosolic and nuclear markers, respectively. Numbers shown are band intensities normalized to tubulin for WCE and cytoplasm lanes, and to c-Jun for nucleus lanes.

(C) Cells were treated as in (A) and Smad2/3 and RNAPII occupancies at the CTGF promoter, encompassing TGFβ-responsive elements, were monitored by ChIP. ChIP signals were normalized to an intergenic region. DBeQ treatment resulted in elevated promoter occupancy by Smad2/3 and RNAPII. Error bars represent standard deviations of mean values from two independent experiments.

Smad regulation via p97-dependent extraction differs signficantly from the steric hinderance models proposed by Inui et al. and Tang et al. Although they are not mutually exclusive, those models depend heavily on where the Smad2/3 transcription factors are ubiquitinated, a point that remains unclear in light of the different results reported (Inui et al., 2011; Tang et al., 2011). In contrast, p97-dependent extraction is likely to be less sensitive to the ubiquitination site(s). However, we cannot rule out that p97 acts on other factors that affect promoter occupancy by Smad2/3. R-Smads undergo complex post-translational modifications, including oligo and poly-ubiquitination, that depend on cell type, expression levels of the Smads, and the strength and persistence of the stimuli. Whether steric hindrance or p97-dependent extraction by Ub are major contributors to Smad regulation will require future experiments in which these models are compared under uniform conditions.

Discussion

The functional outcome of ubiquitination is thought to depend on the number of Ubs attached to the substrate and the types of Ub-Ub linkages in polyUb chain(s) that may be formed. However, the dynamic and often very heterogeneous nature of Ub modifications make the structures and consequences of (poly)Ub signals difficult to define. Adding to this complexity is the fact that, typically, only a small fraction of a substrate protein is ubiquitinated. With transcription activators, at least two pools exist for any particular activator: one free and one bound to chromatin. Because antibodies against specific ubiquitinated proteins generally are unavailable, for most transcription activators it has not been possible to determine which pool is ubiquitinated. These factors compound the difficulty in determining the direct consequence of ubiquitination.

Dynamics of activator ubiquitination

Using LexA-VP16 as a model transcription activator fused with various forms of Ub, we have demonstrated that mono-ubiquitination can lead to transcription inhibition by recruiting the AAA+ ATPase Cdc48. Our results with Ub(V76)-LV differ from those of a previous study (Salghetti et al., 2001) that had employed Ub(A76)-LV. We found that the widely-used Ub(A76)-protein fusion undergoes substantial deubiquitination in vivo, making it difficult to differentiate whether the intact fusion or the deubiquitinated product is responsible for the observed function. With Ub-LV, the ubiquitinated activator does not bind to the promoter stably (Figure 2E) and mutations at the Ub-LV junction demonstrated that deubiquitination is required for transcription (Figure 1B). Ub-conjugate reversibility is similarly important for the physiological regulation of Met4 and R-Smad transcription activators. Interestingly, subsequent transcription activation frequently leads to poly-ubiquitination and degradation of the activator, as was previously shown for LV and Smad2/3 (Salghetti et al., 2001; Gao et al., 2009). This is a common strategy to turn off signaling events. Ub(V76)-LV is stable in wild-type yeast (Figure 1C), which suggests that fusion to Ub(V76) prevents poly-ubiquitination of LV by Met30. We think that this is a consequence of the timing and regulation of Ub attachment. A characteristic of transcription-coupled poly-ubiquitination is that the activator is “marked” for ubiquitination, typically via phosphorylation by coactivator(s) that are part of the transcription machinery (Lipford et al., 2005). In this way, activator ubiquitination and degradation are orchestrated to follow one or more rounds of transcription. In the case of Ub(V76)-LV, because the transcription factor is synthesized with the Ub signal already attached, the lifetime of DNA-bound Ub(V76)-LV may be too brief to recruit the transcription machinery needed to mark the activator for Met30-dependent ubiquitination. In the cases of Met4 and Smad2/3, mono- or oligo-ubiquitination is independent of the transcription machinery and prevents transcription by destabilizing activator-DNA interactions even before higher-order transcription complexes can assemble. Thus, the activators we examined here exemplify how mono- and poly-ubiquitination regulate two different phases of transcription with different consequences. Notably, although Cdc48 mediates the inhibitory effect of mono- or oligo-ubiquitination, in the cases of Ub(L8A,V76)-LV and Met4(K163R), it does not appear to be required for the degradation of the poly-ubiquitinated transcription factors (Figure S4).

An unexpected role for mono-ubiquitination and Cdc48 in inhibiting transcription

The 26S proteasome often employs the segregase activity of Cdc48 to remove poly-ubiquitinated proteins from tightly-bound partners. This has been demonstrated recently for multiple chromatin-bound proteins that include yeast α2 and RNAPII, which directly interact with DNA (Verma et al., 2011; Wilcox and Laney, 2009), and Cdt1, Aurora kinase B, and L3MBTL1, which are bound to chromatin or its associated proteins (Acs et al., 2011; Ramadan et al., 2007; Raman et al., 2011). In most cases, Cdc48 is recruited by poly-Ub, yet the fates of the substrates differ. Whereas Aurora Kinase B is released as a stable protein, other substrates are degraded by the proteasome. How specificity of Cdc48 is governed and what properties determine the different fates of substrates are key unanswered questions.

To our surprise, for LexA, a single Ub is sufficient to recruit Cdc48 and promote dissociation from DNA. Cdc48 and many of its cofactors bind to Ub (Ye, 2006), but specificity for mono- or poly-Ub is not well characterized. Yeast Ufd1 interacts with both mono- and poly-Ub, but its affinity for mono-Ub is quite weak (Park et al., 2005). We think it is unlikely that mono-Ub is the only feature that Cdc48 and its cofactors recognize in this process. First, the mono-Ub moiety by itself is not a very distinctive signal. In vivo, a large pool of Ub exists in a dynamic equilibrium of conjugated and unconjugated states; all of these are potential competitors for binding to Cdc48:Ufd1:Npl4 complexes. Secondly, Ub(V76)-LV in our experimental system was expressed at high levels from either the ACT1 or ADH promoters and was found to be broadly distributed in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Figure 2D). In all of our reporter gene assays, a single LexA operator-driven LacZ gene was inserted at the endogenous HO locus. Therefore, there was a large pool of Ub(V76)-LV not associated with chromatin that in principal would have been available to compete with DNA-bound Ub(V76)-LV for binding by Cdc48:Ufd1:Npl4. Nonetheless, despite the high potency of the LV activator, transcription activation by Ub(V76)-LV was barely detectable. Thus, the Cdc48 machinery was remarkably efficient in preventing activation despite the high total concentration of Ub(V76)-LV and other mono-Ub conjugates.

Modification at DNA damage foci with the Ub-like protein SUMO recently was found to recruit Cdc48 activity via a SUMO-interacting motif (SIM) in the Ufd1 adaptor protein (Bergink et al., 2013; Hannich et al., 2005; Nie et al., 2012). We therefore investigated possible involvement of SUMO in the regulation of Ub(V76)-LV. Neither inactivation of SUMO (Figure S6A) nor deletion of the SIM motif from Ufd1 (Figure S6B) significantly affected LacZ transcription. Thus, SUMO does not contribute to the Cdc48-mediated transcription repression in this system. In addition to Ub, other features of the chromatin environment might help to recruit Cdc48 to the promoter. One possibility is that Cdc48 or its cofactor(s) has intrinsic affinity for naked DNA, which is commonly found at yeast UAS and promoter regions, as well as at sites of DNA damage. Low-affinity, non-specific interactions with DNA or chromatin in combination with specific interactions with Ub may explain how Cdc48 recognizes Ub(V76)-LV with high specificity. In addition, proteins involved in transcriptional regulation may interact with Cdc48 that, in combination with Ub, is able to recruit Cdc48 efficiently. Further studies will be required to explore these possibilities.

Although Ub is best known as a signal for protein degradation, non-proteolytic functions of Ub are gaining recognition. In the cases of the transcriptional activators described here, either degradation or non-proteolytic extraction by Cdc48 could, in principal, accomplish “down-regulation”. Why, then, do these systems employ a non-proteolytic mechanism? Unlike ubiquitination coupled to degradation, ubiquitination coupled to non-proteolytic extraction has the potential advantage of preserving the functional activator protein. This latter scenario could facilitate rapid switching between “on” and “off” states of transcription. We expect that this mode of nonproteolytic extraction would be particularly useful when substantial new protein synthesis is difficult or detrimental. For example, in the yeast MET gene network, deubiquitination of Met4 could promote rapid activation of the pathway even when overall protein synthesis is limited by methionine depletion. Although the ubiquitination substrates we have described here all are transcription factors, we envision that Cdc48 can act similarly on other mono- or oligo-ubiquitinated proteins if an additional targeting element(s) is present.

Experimental Procedures

Yeast strains and plasmids

Manipulations of S. cerevisiae employed standard techniques. Table S1 lists strains used in this study. The reporter gene LacZ under the control of four tandem LexA operators and the GAL1 minimal promoter (pSH1834, Invitrogen) was cloned into pM4297 or pM4366 (Voth et al., 2001) and then integrated into the HO locus of each strain. Site-specific integration was verified by PCR. Where indicated, the hybrid LexA operator with the sequence CCGTACATCCATACAG replaced the four tandem wild-type operators.

For analysis of Met4 localization, a CEN plasmid expressing 3xHAMet4 from the native MET4 promoter was transformed into strains with endogenous MET4 disrupted. The 3xHA tag was inserted in-frame at nucleotide 45 of the MET4 open-reading frame (Lee et al., 2010).

For LV and Ub-LV activators, CEN pRS vectors with promoters of different strengths were used to achieve different expression levels (ATCC 87669). The Ub-LV activators initially were expressed from the ACT1 promoter (Salghetti et al., 2001). Because LV is toxic in yeast, low expression levels were preferred and the CYC1 promoter was used. For comparisons, activators were always expressed from the same promoter; nonetheless, similar results were obtained for Ub-LV proteins regardless of which promoter was used. Point mutations were made using the QuickChange® II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) and verified by sequencing.

β-Galactosidase activity assay

Yeast were grown to mid-log phase in liquid culture. An equivalent of 1 ml × 0.1 OD600 of cells was pelleted and resuspended in 100 μl of 140 mM Pipes (pH 7.2), 2.5% Triton X-100, and 0.5 mM fluorescein di-β-D-galactopyranoside (FDG) in wells of a 96-well plate (Hoffman et al., 2002). β-Galactosidase activity was quantified as the rate of FDG hydrolysis monitored continuously on a BioTek Synergy microplate reader for 1 h at 37 °C (Ex 485 nm, Em 530 nm).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Cdc48 extracts Ub-LexA-VP16 from DNA independently of proteasomal degradation.

Ub-LexA-VP16 deubiquitination efficiency correlates with transcriptional activity.

Mono-ubiquitin fused to LexA-VP16 is sufficient to recruit Cdc48.

Cdc48/p97 regulates promoter occupancy by Met4 in yeast and R-Smads in mammals.

Acknowledgments

We thank William Tansey, Mike Tyers, David Stillman, Dan Finley, Yihong Ye, Traci Lee, Xiaobing Shi, and Laurie Stargell for providing strains, reagents and advice for this work. T.Y. is grateful to Joan and Ron Conaway for resources and support at the initial stage of this project. This work was supported by the Boettcher Foundation and NIH grant R01GM098401 to T.Y. T.Y. is a Boettcher Investigator. T.Y. conceived the study. A.N and T.Y. performed the experiments. A.N., R.E.C. and T.Y. designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental Data: Supplemental Data include Supplemental Experimental Procedures, Supplemental References, two tables and six figures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acs K, Luijsterburg MS, Ackermann L, Salomons FA, Hoppe T, Dantuma NP. The AAA-ATPase VCP/p97 promotes 53BP1 recruitment by removing L3MBTL1 from DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1345–1350. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer CT, Burdine L, Liu B, Ferdous A, Johnston SA, Kodadek T. Physical and functional interactions of monoubiquitylated transactivators with the proteasome. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21789–21798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803075200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmair A, Finley D, Varshavsky A. In vivo half-life of a protein is a function of its amino-terminal residue. Science. 1986;234:179–186. doi: 10.1126/science.3018930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergink S, Ammon T, Kern M, Schermelleh L, Leonhardt H, Jentsch S. Role of Cdc48/p97 as a SUMO-targeted segregase curbing Rad51-Rad52 interaction. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:526–532. doi: 10.1038/ncb2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TF, Brown SJ, Minond D, Nordin BE, Li K, Jones AC, Chase P, Porubsky PR, Stoltz BM, Schoenen FJ, et al. Reversible inhibitor of p97, DBeQ, impairs both ubiquitin-dependent and autophagic protein clearance pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4834–4839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015312108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmitrova M, Younes-Cauet G, Oertel-Buchheit P, Porte D, Schnarr M, Granger-Schnarr M. A new LexA-based genetic system for monitoring and analyzing protein heterodimerization in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;257:205–212. doi: 10.1007/s004380050640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdous A, Sikder D, Gillette T, Nalley K, Kodadek T, Johnston SA. The role of the proteasomal ATPases and activator monoubiquitylation in regulating Gal4 binding to promoters. Genes Dev. 2007;21:112–123. doi: 10.1101/gad.1493207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flick K, Ouni I, Wohlschlegel JA, Capati C, McDonald WH, Yates JR, Kaiser P. Proteolysis-independent regulation of the transcription factor Met4 by a single Lys 48-linked ubiquitin chain. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:634–641. doi: 10.1038/ncb1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S, Alarcon C, Sapkota G, Rahman S, Chen PY, Goerner N, Macias MJ, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Massague J. Ubiquitin ligase Nedd4L targets activated Smad2/3 to limit TGF-beta signaling. Mol Cell. 2009;36:457–468. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng F, Wenzel S, Tansey WP. Ubiquitin and proteasomes in transcription. Annu Rev of Biochem. 2012;81:177–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-052110-120012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannich JT, Lewis A, Kroetz MB, Li SJ, Heide H, Emili A, Hochstrasser M. Defining the SUMO-modified proteome by multiple approaches in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4102–4110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413209200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman GA, Garrison TR, Dohlman HG. Analysis of RGS proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods in Enzymol. 2002;344:617–631. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)44744-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inui M, Manfrin A, Mamidi A, Martello G, Morsut L, Soligo S, Enzo E, Moro S, Polo S, Dupont S, et al. USP15 is a deubiquitylating enzyme for receptor-activated SMADs. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1368–1375. doi: 10.1038/ncb2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch S, Rumpf S. Cdc48 (p97): a “molecular gearbox” in the ubiquitin pathway? Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser P, Flick K, Wittenberg C, Reed SI. Regulation of transcription by ubiquitination without proteolysis: Cdc34/SCF(Met30)-mediated inactivation of the transcription factor Met4. Cell. 2000;102:303–314. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TA, Jorgensen P, Bognar AL, Peyraud C, Thomas D, Tyers M. Dissection of combinatorial control by the Met4 transcriptional complex. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:456–469. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-05-0420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Brooks CL, Wu-Baer F, Chen D, Baer R, Gu W. Mono- versus polyubiquitination: differential control of p53 fate by Mdm2. Science. 2003;302:1972–1975. doi: 10.1126/science.1091362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipford JR, Smith GT, Chi Y, Deshaies RJ. A putative stimulatory role for activator turnover in gene expression. Nature. 2005;438:113–116. doi: 10.1038/nature04098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meerang M, Ritz D, Paliwal S, Garajova Z, Bosshard M, Mailand N, Janscak P, Hubscher U, Meyer H, Ramadan K. The ubiquitin-selective segregase VCP/p97 orchestrates the response to DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1376–1382. doi: 10.1038/ncb2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie M, Aslanian A, Prudden J, Heideker J, Vashisht AA, Wohlschlegel JA, Yates JR, 3rd, Boddy MN. Dual recruitment of Cdc48 (p97)-Ufd1-Npl4 ubiquitin-selective segregase by small ubiquitin-like modifier protein (SUMO) and ubiquitin in SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase-mediated genome stability functions. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:29610–29619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.379768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouni I, Flick K, Kaiser P. A transcriptional activator is part of an SCF ubiquitin ligase to control degradation of its cofactors. Mol Cell. 2010;40:954–964. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouni I, Flick K, Kaiser P. Ubiquitin and transcription: The SCF/Met4 pathway, a (protein) complex issue. Transcription. 2011;2:135–139. doi: 10.4161/trns.2.3.15903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkaynak E, Finley D, Varshavsky A. The yeast ubiquitin gene: head-to-tail repeats encoding a polyubiquitin precursor protein. Nature. 1984;312:663–666. doi: 10.1038/312663a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Isaacson R, Kim HT, Silver PA, Wagner G. Ufd1 exhibits the AAA-ATPase fold with two distinct ubiquitin interaction sites. Structure. 2005;13:995–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polevoda B, Sherman F. N-terminal acetyltransferases and sequence requirements for N-terminal acetylation of eukaryotic proteins. J Mol Biol. 2003;325:595–622. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan K, Bruderer R, Spiga FM, Popp O, Baur T, Gotta M, Meyer HH. Cdc48/p97 promotes reformation of the nucleus by extracting the kinase Aurora B from chromatin. Nature. 2007;450:1258–1262. doi: 10.1038/nature06388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman M, Havens CG, Walter JC, Harper JW. A genome-wide screen identifies p97 as an essential regulator of DNA damage-dependent CDT1 destruction. Mol Cell. 2011;44:72–84. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rape M, Hoppe T, Gorr I, Kalocay M, Richly H, Jentsch S. Mobilization of processed, membrane-tethered SPT23 transcription factor by CDC48(UFD1/NPL4), a ubiquitin-selective chaperone. Cell. 2001;107:667–677. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00595-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DM, Glickman MH, Larsen CN, Dhruvakumar S, Finley D. Active site mutants in the six regulatory particle ATPases reveal multiple roles for ATP in the proteasome. EMBO J. 1998;17:4909–4919. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.17.4909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salghetti SE, Caudy AA, Chenoweth JG, Tansey WP. Regulation of transcriptional activation domain function by ubiquitin. Science. 2001;293:1651–1653. doi: 10.1126/science.1062079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuberth C, Buchberger A. UBX domain proteins: major regulators of the AAA ATPase Cdc48/p97. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2360–2371. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8072-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang LY, Yamashita M, Coussens NP, Tang Y, Wang X, Li C, Deng CX, Cheng SY, Zhang YE. Ablation of Smurf2 reveals an inhibition in TGF-beta signalling through multiple mono-ubiquitination of Smad3. EMBO J. 2011;30:4777–4789. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Horst A, de Vries-Smits AM, Brenkman AB, van Triest MH, van den Broek N, Colland F, Maurice MM, Burgering BM. FOXO4 transcriptional activity is regulated by monoubiquitination and USP7/HAUSP. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1064–1073. doi: 10.1038/ncb1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma R, Oania R, Fang R, Smith GT, Deshaies RJ. Cdc48/p97 mediates UV-dependent turnover of RNA Pol II. Mol Cell. 2011;41:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voth WP, Richards JD, Shaw JM, Stillman DJ. Yeast vectors for integration at the HO locus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:E59–59. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.12.e59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Suzuki H, Kato M. Roles of mono-ubiquitinated Smad4 in the formation of Smad transcriptional complexes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;376:288–292. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox AJ, Laney JD. A ubiquitin-selective AAA-ATPase mediates transcriptional switching by remodelling a repressor-promoter DNA complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1481–1486. doi: 10.1038/ncb1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao T, Ndoja A. Regulation of gene expression by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y. Diverse functions with a common regulator: ubiquitin takes command of an AAA ATPase. J Struct Biol. 2006;156:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y, Meyer HH, Rapoport TA. Function of the p97-Ufd1-Npl4 complex in retrotranslocation from the ER to the cytosol: dual recognition of nonubiquitinated polypeptide segments and polyubiquitin chains. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:71–84. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.