Abstract

Background and Purpose

Acute stroke treatments are underutilized primarily due to delayed hospital arrival. Using a community based participatory research approach, we explored stroke self-efficacy, knowledge and perceptions of stroke among a predominately African American population in Flint, Michigan.

Methods

In March 2010, a survey was administered to youth and adults after religious services at three churches and one church health day. The survey consisted of vignettes (12 stroke, 4 non-stroke) to assess knowledge of stroke warning signs and behavioral intent to call 911. The survey also assessed stroke self-efficacy, personal knowledge of someone who had had a stroke, personal history of stroke and barriers to calling 911. Linear regression models explored the association of stroke self-efficacy with behavioral intent to call 911 among adults.

Results

Two hundred forty two adults and 90 youth completed the survey. Ninety two percent of adults and 90% of youth respondents were African American. Responding to 12 stroke vignettes, adults would call 911 in 72% (sd=0.26) of the vignettes while youth would call 911 in 54% (sd=0.29) (p<0.001). Adults correctly identified stroke in 51% (sd=0.32) of the stroke vignettes and youth in 46% (sd=0.28) of the stroke vignettes (p=0.28). Stroke self-efficacy predicted behavioral intent to call 911 (p=0.046).

Conclusion

In addition to knowledge of stroke warning signs, behavioral interventions to increase both stroke self-efficacy and behavioral intent may be useful for helping people make appropriate 911 calls for stroke. A community based participatory research approach may be effective in reducing stroke disparities.

Keywords: Stroke, African Americans, Community Based Participatory Research

Acute stroke treatments are underutilized. Some studies have found that African Americans (AAs) are less likely to receive acute stroke treatments than European Americans (EAs).1, 2 The primary reason patients do not receive acute stroke treatment is hospital arrival outside the treatment window.3 Prehospital delay is greater among AAs than EAs.4 Although prompt 911 calls decrease prehospital delay and hospital triage times,5 emergency medical service (EMS) is notified in fewer than 40% of acute stroke cases.6 Someone other than the patient calls 911 in up to 95% of all acute stroke situations.6

To address the underutilization of acute stroke treatment, behavioral interventions have focused on increasing knowledge of stroke warning signs.7–9 Researchers have consistently found that, while knowledge is important, it is not enough to increase health behavior - a finding that is also true for stroke.10, 11 Individuals with a prior stroke or more knowledge about stroke warning signs are not more likely to call 911.5, 12 Little research has been done to explore other factors that may influence the decision to call 911 such as self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is a person’s perception of his or her abilities and it is this perception that often influences behavior rather than his or her actual ability.13 Self-efficacy is an important component in both acute and chronic health behaviors. For example, self-efficacy has been associated with greater intent to seek emergency care for acute myocardial infarction.14 Furthermore, baseline self-efficacy and changes in self-efficacy during behavioral interventions are associated with behavior change such as smoking cessation, improved medication adherence and diabetes self-management.15–17 Self-efficacy is also associated with decreased health care utilization and improved self-reported health and disability.18, 19

To inform future behavioral interventions to increase utilization of acute stroke treatments among AAs, we conducted a community based participatory research (CBPR) project in Flint, Michigan. Flint is an ideal population to study factors related to the behavioral intent to call 911 because of the high age-adjusted stroke hospitalization rate and stroke mortality rate that is 1.5 times higher than the United States, suggesting a great need for stroke education.20 The purpose of this study was to assess knowledge of stroke warning signs, behavioral intent to call 911 and barriers to calling 911 among a high risk population of AA adults and youth. We also sought to determine whether respondents with high levels of stroke-self-efficacy had higher behavioral intent to call 911 compared to respondents with low levels of stroke self-efficacy.

Methods

Setting and Research Team

Flint has a population of 117,068 people, of which 53% are AAs and 41% are EAs.21 It is the birthplace of General Motors and like many cities in the industrial midwest United States has seen the fall of its manufacturing industry leaving many of its residents unemployed. Today, over one in four people in Flint live in poverty.21

One of the foundations of a CBPR approach is the establishment of a team of community and academic partners who collaboratively design a study that produces outcomes that will benefit the community.22 For this research the team consisted of: 1) academic partners - University of Michigan stroke neurologists and experts in Health Behavior and Health Education; and 2) community partners - founders of Bridges into the Future, a faith-based AA community organization. Input and approval was also obtained from the Community-Based Organization Partners (CBOP) of Flint. This is an alliance of community-based organizations that was established to strengthen the influence of community partners involved in CBPR projects in Flint.23

Design of Stroke Vignettes

Members of the research team, in particular the community partners, felt that the validated, stroke action test (STAT),24 was not suitable for their community. The community partners felt that due to its length and situations that are not customary in their community (e.g. going to the gym) respondents would have difficulty relating to and completing the STAT. Thus, the academic-community partnership collaboratively developed a series of new stroke vignettes to evaluate knowledge of stroke warning signs and behavioral intent to call 911. The intent of each vignette was to describe a person’s symptoms either in a manner highly suggestive of an acute stroke or in a manner not suggestive of an acute stroke. The vignettes underwent content validation by a team of stroke experts. Next, a stroke neurologist (LS), health behavior and health education expert (JM) and the community partners (SB, SF) conducted a focus group with AA youth to evaluate the vignettes. Vignettes then underwent a series of individual cognitive interviews with AA youth and adults to assess their readability and interpretation.

Population

The sample of 4 predominately AA churches represented various geographical locations of Flint. Members of the research team met individually with each church pastor to introduce themselves and the project goals. Each church’s Senior Pastor reviewed and approved the surveys. In March of 2010, the written survey was administered to youth (target age 11–14 years) and adults at 4 sites – after religious services at 3 churches and, by community partner request, at a church health seminar. Youth were included based on the recommendation of the community partners who identified that youth have a key role in community sustainability and frequently spend time with their grandparents who are at risk for stroke. At least one academic partner and one community partner were present for every survey administration. Five dollars was given to each participant after survey completion. Approval was obtained from the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board.

Survey Instrument

First, prior experience with stroke was queried via: 1) Have you ever had a stroke? (adults); 2) Do you personally know someone who has had a stroke? (youth and adults). To investigate behavioral intent to call 911 when the diagnosis of stroke was provided, respondents were asked: If you think someone is having a stroke, who is the first person you would call? Response options included spouse/partner, pastor, parent, child, neighbor, friend, doctor, ambulance or other. Next a series of 16 vignettes (12 stroke vignettes and 4 non-stroke vignettes), were queried. The stroke vignettes included common stroke symptoms: hemiparesis, dysarthria, aphasia, visual changes, dizziness/imbalance and severe headache.25, 26 The four non-stroke vignettes were chest pain, musculoskeletal pain, orthostatic hypotension and epistaxis. For each vignette, respondents selected one option - ‘stroke,’ ‘no stroke,’ and ‘don’t know.’ A follow up question accompanied each vignette “If this happened, what would you do first?” Response options included: 1) call doctor’s office immediately; 2) wait a couple of hours, then decide; 3) call a family member or friend immediately; and 4) call 911 immediately. Identifying stroke and behavioral intent to call 911 were scored separately withone point given for identifying stroke and behavioral intent to call 911. each correct response. Vignettes with missing responses were scored as incorrect (range 2–10%).

Additionally, adult respondents were queried on self-efficacy and barriers to calling 911. Stroke self-efficacy was assessed using 2 statements: 1) I would not be able to tell if someone is having a stroke; 2) If I saw someone having a stroke I would not know what to do. Statements were assessed on a Likert scale ranging from 1, strongly agree, to 4, strongly disagree. The inter-item correlation was 0.43 so the scores were combined to form a stroke self-efficacy scale ( mean=5.3, sd= 1.6). Scores ranged from 2, low self-efficacy, to 8, high self-efficacy.

Respondents were also asked their level of agreement on a Likert scale from 1, strongly agree, to 4, strongly disagree, with statements querying barriers to calling 911. Barriers included mode of transportation, cost, religious beliefs, embarrassment, access to ambulance and knowing someone with a prior bad hospital experience. All responses were analyzed as agree (strongly agree and agree) vs. disagree (strongly disagree and disagree). The survey had a Flesch Kincaid reading grade level of 5.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographics of respondents, prior stroke experience, behavioral intent to call 911 when diagnosis of stroke was provided and barriers to calling 911. The mean of the percent of correct responses for the stroke vignettes and mean of the percent of incorrect responses for the 4 non-stroke vignettes was calculated separately for the youth and adults. Adult and youth knowledge of stroke warning signs and behavioral intent to call 911 were compared using t-tests or chi-square tests. Reliability of the novel vignettes was evaluated using Cronbach’s α.

Among adults, linear regression was then used to evaluate the association between stroke self-efficacy (continuous) and behavioral intent to call 911 (continuous), the dependent variable. Linear regression models were run unadjusted and adjusted for gender, age (continuous), education (some college vs. no college), personal history of stroke (yes vs. no) and personal knowledge of someone who had had a stroke (yes vs. no). Regression diagnostic procedures yielded evidence of a skewed distribution of model residuals. Thus, robust standard errors were used to compute confidence intervals and p-values. All tests were 2-tailed and the probability of Type 1 error was set at 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Results

A total of 332 individuals participated in the survey. Two hundred forty two were adults and 90 were youth. Demographics, education and prior stroke experience are presented in Table 1. The majority of respondents were AA (92% adults, 90% youth). The median age of adult respondents was 47 years (IQR: 33–54) and youth respondents was 13 years (IQR: 11–14). The majority of respondents know someone who had had a stroke (84% adults, 61% youth).

Table 1.

Demographics and stroke experience among adult and youth respondents in Flint, Michigan.

| Variable | Adult Respondents (n=242) n (%) |

Youth Respondents (n=90) n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (median (IQR)) | 47 (33–54) | 13 (11–14) |

| Female | 170 (71) | 48 (55) |

| African American | 218 (92) | 77 (90) |

| Non-Hispanic | 204 (98) | 68 (82) |

| Education | ||

| Less than High School | 7 (3) | |

| GED | 11(5) | |

| High School Graduate | 66 (28) | |

| Trade School | 10 (4) | |

| Some College | 71 (30) | |

| College Graduate | 52 (22) | |

| Advanced Degree | 16 (7) | |

| Stroke Experience | ||

| Personal history of stroke | 12 (5) | |

| Personal knowledge of someone who had had a stroke | 199 (84) | 55 (61) |

When provided the diagnosis of stroke, 89% of adult and 78% of youth respondents would first call 911 (p=0.01). Among adult respondents, the reliability of the 12-item stroke vignettes was good (Cronbach’s α = 0.88 for stroke warning signs and Cronbach’s α = 0.83 for behavioral intent to call 911). Similarly good reliability was found among the youth respondents (Cronbach’s α = 0.82 for stroke warning signs and Cronbach’s α = 0.84 for behavioral intent to call 911). Stroke vignettes were correctly identified as stroke in 51% (sd=0.32) of the vignettes by adults and 46% (sd=0.28) by youth (p=0.28). Adults indicated that they would call 911 in 72% (sd=0.26) of the stroke vignettes compared with youth who would call 911 in 54% (sd=0.29) (p<0.001). Respondents were least likely to call 911 for sudden headache (51% adult, 31% youth) and were most likely to call 911 for dysarthria (91% adult, 63% youth). On the other hand, adult respondents identified a stroke in 25% (sd=0.28) and youth in 28% (sd=0.27) of the non-stroke vignettes (chest pain, orthostatic hypotension, epistaxis and musculoskeletal pain) (p=0.33). Similarly among the non-emergent vignettes (orthostatic hypotension, epistaxis and musculoskeletal pain), adult respondents would call 911 for 38% (sd=0.39) and youth for 27% (sd=0.33) (p=0.01) of the vignettes.

Adult respondents had limited stroke self-efficacy. Thirty eight percent of adults either strongly agreed or agreed that they would not be able to tell if someone was having a stroke; while, 43% strongly agreed or agreed that they would not know what to do if they witnessed someone having a stroke. Few barriers to calling 911 were endorsed by adult respondents. However, 17% of adult respondents believed that they could transport their loved one to the hospital faster than engaging an ambulance (table 2).

Table 2.

Percent agreement with potential barriers to calling 911 for a witnessed stroke among adults respondents (n=242) in Flint, MI. All statements began with the phrase: “I would not call 911 because…”

| Barrier | Agree n (%) |

|---|---|

| I could get my loved one to the hospital faster than an ambulance | 40 (17) |

| The ambulance costs too much | 14 (6) |

| My personal religious beliefs prevent me from calling | 8 (3) |

| Embarrassed to have my neighbors see an ambulance at my house | 3 (1) |

| An ambulance would not come to my house | 8 (3) |

| I believe that divine healing is more important than medical care provided by physicians | 10 (4) |

| I know someone who had a previous bad experience at a hospital | 8 (3) |

In the unadjusted model, stroke self-efficacy was associated with behavioral intent to call 911 (β=0.020, SE=0.010; p=0.046). After adjustment for demographics, history of stroke and knowing someone who had had a stroke, age (β=0.004, SE=0.001; p=0.001) and stroke self-efficacy (β=0.022, SE=0.011; p=0.034) predicted behavioral intent to call 911 (Table 3).

Table 3.

The results of a multivariable linear regression model exploring the association between self-efficacy and behavioral intent to call 911 among adults (n=214) in Flint, Michigan. R2=0.07

| Factors | Beta | Standard Error | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 0.009 | 0.038 | 0.823 |

| Some college education | 0.009 | 0.038 | 0.806 |

| Age | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Personal knowledge of someone who had had a stroke | −0.013 | 0.045 | 0.771 |

| Personal history of stroke | 0.035 | 0.087 | 0.685 |

| Stroke self-efficacy | 0.022 | 0.011 | 0.034 |

Discussion

Stroke was correctly identified by adult and youth respondents in approximately half of the stroke vignettes. Behavioral intent to call 911 was high when the diagnosis of stroke was provided – a result that is consistent with respondents in Harlem and central Massachusetts.24, 27 Yet, behavioral intent to call 911 was only moderate when assessed using stroke vignettes, where the diagnosis of stroke was not provided. Adult respondents would not call 911 in nearly 1 out of 3 vignettes and youth would not call for nearly 1 out of 2 vignettes. Moreover, the diagnosis of stroke was chosen in approximately 25% of the non-stroke vignettes while over 25% of respondents reported they would call 911 for non-emergent non-stroke vignettes. Youth had lower behavioral intent to call 911 as measured by both providing the diagnosis of stroke and in the stroke vignettes. These results suggest significant need for a community-based intervention, targeting youth and adults separately, to increase knowledge of stroke warning signs and behavioral intent to call 911.

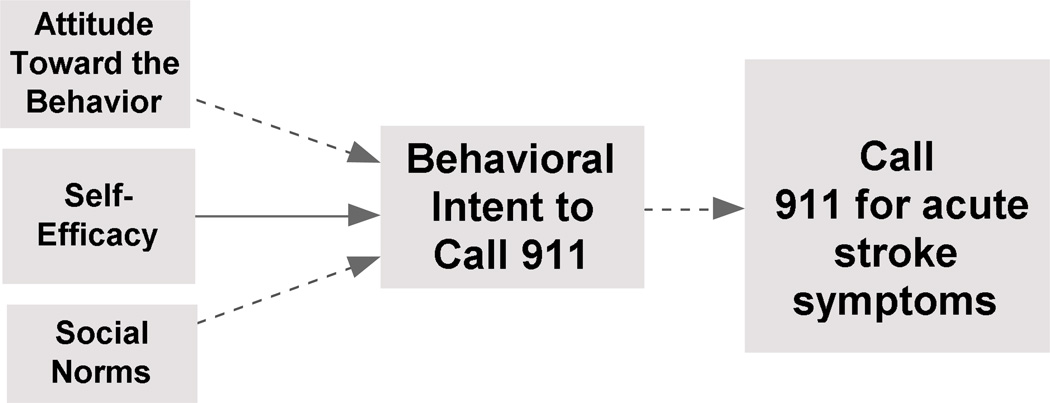

Respondent’s confidence in recognizing stroke and acting appropriately, stroke self-efficacy, was limited. Of interest, after adjusting for sociodemographics, prior history of stroke and knowing someone who had had a stroke, stroke self-efficacy was associated with behavioral intent to call 911. Our model, however, explained 7% of the variation in behavioral intent to call 911 suggesting that other factors contribute to behavioral intent to call 911. The theory of planned behavior, a health behavioral theory, maintains that the most immediate and significant predictor of behavior is the intention to perform the behavior.28 For example, people with higher intent to call 911 will be more likely to actually call 911 when an acute stroke situation arises. The theory of planned behavior proposes that the key determinants of behavioral intent are attitude toward the behavior (e.g. knowledge of stroke warning signs and expected outcome of calling 911), subjective norms (e.g. expectations of social network including family and church) and self-efficacy to perform the behavior (Figure 1). Further exploration of subjective norms and attitude toward calling 911 is needed.

Figure 1.

Cognitive behavioral stroke emergency model based on the study results and the Theory of Planned Behavior. Dashed line=Proposed based on the theory of planned behavior. Solid line=Based on study results.

Based on the results of our survey, self-efficacy may be a target to increase 911 calls for acute stroke. Self-efficacy is derived from and modified by, personal accomplishments (skills mastery), modeling (vicarious experience), verbal persuasion and physiologic states.29 Because participants perform tasks (skills mastery), observe others performing the task (vicarious experience) and receive feedback (verbal persuasion), role playing 911 calls for acute stroke in small groups targets the three most relevant means to increase self-efficacy. Role playing has successfully increased self-efficacy and behavior change in other behavioral interventions, especially in the setting of episodic behaviors where risk to the participant would occur if the behavior is not performed.30–32 Additionally, identifying people experiencing an acute stroke in video scenarios and developing an action plan, forms of skills mastery, may also increase self-efficacy.

Engaging AAs, especially youth, in research is difficult due, in part, to the legacy of the Tuskegee study.33 The community partners helped establish the trust in the Flint community that was needed for this project to take place. Additionally, the community partners were vital in providing insights about measurement to ensure that the survey was appropriate for their community, encouraging data collection from youth, and gaining access to the church populations. For example, the community partners facilitated the introduction of the academic partners and the research project to each church pastor after which approval was obtained to administer the survey after church services. Finally, both community and academic partners were present at the church services and at the time of survey distribution to demonstrate the partnership to the respondents.

Several limitations of the study warrant attention. First, we used a convenience sample of self-selected church-goers which introduces selection bias and limits the generalizability of our findings. The population may be younger than the typical audience for stroke messaging and more highly educated than the population of Flint. Nevertheless, the results show deficiencies in knowledge of stroke warning signs and behavioral intent for high probability stroke scenarios and provided an initial test of stroke vignettes that can be used in future studies. Additionally a church-based cohort may limit the generalizability of the study, but it is an efficient way to sample AAs who are more likely to identify themselves as religious and attend church than EAs.34 Moreover, while we believe the population of Flint is similar to other urban areas, a more broad-based approach for sampling AAs that includes other urban areas would help address concerns about generalizability. Second, the use of closed-ended questions may overestimate knowledge of stroke warning signs and behavioral intent to call 911 compared to open-ended questions.35 Finally, although the study relied on self-report, this is the appropriate data source as we were interested in individuals’ perceptions, knowledge and self-efficacy.

Summary

Knowledge of stroke warning signs and behavioral intent to calling 911 for stroke were moderate while stroke self-efficacy was more limited among predominately AA respondents in an urban community. Stroke self-efficacy was associated with behavioral intent to call 911. The results of this survey of church-going AA adults and youth in an urban community suggest the need for further stroke education about stroke warning signs and interventions targeting behavioral intent to call 911 and stroke self-efficacy. Finally, CBPR is an effective approach to developing, administering and analyzing a community stroke survey and may be a means to reduce stroke disparities.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank New Jerusalem Full Gospel Baptist Church, Refuge Temple and Ebeneezer Ministries for their support.

Sources of Funding

Dr. Skolarus is supported by an American Academy of Neurology Foundation Clinical Research Training Fellowship. Dr. Brown is supported by an NINDS career development award (K23 NS051202). Dr. Kerber is supported by an NCRR career development award (K23 RR024009).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Schumacher HC, Bateman BT, Boden-Albala B, Berman MF, Mohr JP, Sacco RL, Pile-Spellman J. Use of thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke: Analysis of the nationwide inpatient sample 1999 to 2004. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2007;50:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwamm LH, Reeves MJ, Pan W, Smith EE, Frankel MR, Olson D, Zhao X, Peterson E, Fonarow GC. Race/ethnicity, quality of care, and outcomes in ischemic stroke. Circulation. 2010;121:1492–1501. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.881490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleindorfer D, Kissela B, Schneider A, Woo D, Khoury J, Miller R, Alwell K, Gebel J, Szaflarski J, Pancioli A, Jauch E, Moomaw C, Shukla R, Broderick JP. Eligibility for recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in acute ischemic stroke: A population-based study. Stroke. 2004;35:e27–e29. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000109767.11426.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Prehospital and hospital delays after stroke onset--united states, 2005–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:474–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schroeder EB, Rosamond WD, Morris DL, Evenson KR, Hinn AR. Determinants of use of emergency medical services in a population with stroke symptoms : The second Delay in Accessing Stroke Healthcare (DASH II) study. Stroke. 2000;31:2591–2596. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.11.2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wein TH, Staub L, Felberg R, Hickenbottom SL, Chan W, Grotta JC, Demchuk AM, Groff J, Bartholomew LK, Morgenstern LB. Activation of emergency medical services for acute stroke in a nonurban population: The T.L.L. Temple foundation stroke project. Stroke. 2000;31:1925–1928. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.8.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morgenstern LB, Gonzales NR, Maddox KE, Brown DL, Karim AP, Espinosa N, Moye LA, Pary JK, Grotta JC, Lisabeth LD, Conley KM. A randomized, controlled trial to teach middle school children to recognize stroke and call 911: The kids identifying and defeating stroke project. Stroke. 2007;38:2972–2978. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.490078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleindorfer D, Miller R, Sailor-Smith S, Moomaw CJ, Khoury J, Frankel M. The challenges of community-based research: The beauty shop stroke education project. Stroke. 2008;39:2331–2335. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.508812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams O, Noble JM. 'Hip-hop' stroke: A stroke educational program for elementary school children living in a high-risk community. Stroke. 2008;39:2809–2816. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.513143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook PA, Bellis MA. Knowing the risk: Relationships between risk behaviour and health knowledge. Public Health. 2001;115:54–61. doi: 10.1038/sj/ph/1900728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohida T, Sakurai H, Mochizuki Y, Kamal AMM, Takemura S, Minowa M, Kawahara K. Smoking prevalence and attitudes toward smoking among japanese physicians. JAMA. 2001;285:2643–2648. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.20.2643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams LS, Bruno A, Rouch D, Marriott DJ. Stroke patients' knowledge of stroke. Influence on time to presentation. Stroke. 1997;28:912–915. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.5.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strecher VJ, McEvoy DeVellis B, Becker MH, Rosenstock IM. The role of self-efficacy in achieving health behavior change. Health Education & Behavior. 1986;13:73–92. doi: 10.1177/109019818601300108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zapka JG, Oakes JM, Simons-Morton DG, Mann NC, Goldberg R, Sellers DE, Estabrook B, Gilliland J, Linares AC, Benjamin-Garner R, McGovern P. Missed opportunities to impact fast response to ami symptoms. Patient Education and Counseling. 2000;40:67–82. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwickl B, Wu AW, Committee PC Group AACTG. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: The adherence instruments. AIDS care. 2000;12:255. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Butler PM, Arnold MS, Fitzgerald JT, Feste CC. Patient empowerment. Results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:943–949. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.7.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gwaltney CJ, Metrik J, Kahler CW, Shiffman S. Self-efficacy and smoking cessation: A meta-analysis. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23:56–66. doi: 10.1037/a0013529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lorig K, Gonzalez VM, Ritter P. Community-based spanish language arthritis education program: A randomized trial. Medical Care. 1999;37:957–963. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199909000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, Sobel DS, William Brown BJ, Bandura A, Gonzalez VM, Laurent DD, Holman HR. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Medical Care. 2001;39:1217–1223. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson BE, Lyon-Callo SK, Heiler PL, Miller HL, Theisen VJ. Impact of Heart Disease and Stroke in Michigan: 2008 Report on Surveillance. Lansing, MI: Michigan Department of Community Health, Bureau of Epidemiology, Chronic Disease Epidemiology Section; [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bureau C. [cited 2010 May 4, 2010];State and County Quick facts. 2000 [updated 2000;]; Available from: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/26/2629000.html.

- 22.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffith D, Allen J, DeLoney E, Robinson K, Lewis E, Campbell B, Morrel-Samuels S, Sparks A, Zimmerman M, Reischl T. Community-based organizational capacity building as a strategy to reduce racial health disparities. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2010;31:31–39. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0202-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Billings-Gagliardi S, Mazor KM. Development and validation of the stroke action test. Stroke. 2005;36:1035–1039. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000162716.82295.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldstein LB, Simel DL. Is this patient having a stroke? JAMA. 2005;293:2391–2402. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.19.2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kleindorfer DO, Miller R, Moomaw CJ, Alwell K, Broderick JP, Khoury J, Woo D, Flaherty ML, Zakaria T, Kissela BM. Designing a message for public education regarding stroke: Does fast capture enough stroke? Stroke. 2007;38:2864–2868. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.484329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willey JZ, Williams O, Boden-Albala B. Stroke literacy in central harlem: A high-risk stroke population. Neurology. 2009;73:1950–1956. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c51a7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological review. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parle M, Maguire P, Heaven C. The development of a training model to improve health professionals' skills, self-efficacy and outcome expectancies when communicating with cancer patients. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;44:231–240. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00148-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilchrist LD, Schinke SP. Coping with contraception: Cognitive and behavioral methods with adolescents. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1983;7:379–388. doi: 10.1007/BF01187166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Washington CD, Wilson TS, Koob JJ, Davis DR, Ledezma G, Davantes B. The effects of hiv/aids intervention groups for high-risk women in urban clinics. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1918–1922. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.12.1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rajakumar K, Thomas SB, Musa D, Almario D, Garza MA. Racial differences in parents' distrust of medicine and research. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:108–114. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kosmin BAME, Keysar A. [cited April 28, 2010];American religious identification survey. 2006 [updated 2006;]; Available from: http://www.gc.cuny.edu/faculty/research_briefs/aris/aris_index.htm.

- 35.Kleindorfer D, Khoury J, Broderick JP, Rademacher E, Woo D, Flaherty ML, Alwell K, Moomaw CJ, Schneider A, Pancioli A, Miller R, Kissela BM. Temporal trends in public awareness of stroke: Warning signs, risk factors, and treatment. Stroke. 2009;40:2502–2506. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.551861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]