Abstract

We evaluated the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa carrying blaIMP, a metallo-β-lactamase gene, and the efficacy of ceftazidime, imipenem-cilastatin, and ciprofloxacin in the endogenous bacteremia model. The presence of blaIMP did not practically change the virulence of the parent strain, and ciprofloxacin was effective against infection with P. aeruginosa carrying blaIMP.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a major opportunistic pathogen in immunosuppressed patients. Carbapenems have been the predominant antibiotic class for treatment of P. aeruginosa infection because of their stability against most β-lactamases. However, metallo-β-lactamases able to hydrolyze carbapenem have been reported, and P. aeruginosa strains carrying metallo-β-lactamase genes are a recent clinical threat (1, 3, 12). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the virulence of P. aeruginosa carrying the blaIMP gene by using the epithelial cell monolayer system and mouse models of endogenous bacteremia. Moreover, we examined the efficacy of ceftazidime (CAZ), imipenem-cilastatin (IPM-CS), and ciprofloxacin (CIP) in the endogenous bacteremia model using P. aeruginosa carrying blaIMP.

P. aeruginosa PAO1 wild type (WT), used as the parent strain, is invasive and penetrates MDCK cell monolayers within 3 h after infection (2). The vector control strain pMS360 was PAO1 transformed with the vector plasmid pMS360 with a broad host range and streptomycin resistance (7). The strain pMS363 (7) was PAO1 transformed with the vector pMS363, which includes blaIMP and an integrase gene (8), in vector plasmid pMS360. The PAO1 WT-derived MexAB-OprM deletion mutant (ΔmexAB-oprM) (5), which does not penetrate MDCK cell monolayers until 6 h, was used as a negative control. All strains exhibited the same growth kinetics in Luria-Bertani broth. Noninvasive rabbit enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli RDEC-1 was used as another negative control and as an internal control of monolayer integrity (2).

MICs of all β-lactams for the pMS363 strain, except that of aztreonam (ATM), rose by up to 4- to 64-fold compared to those for the parent WT, whereas those for the pMS360 strain were similar to those for the WT. MICs of fluoroquinolones for pMS360 and pMS363 strains were identical to those for the WT (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibilities of P. aeruginosa WT, pMS360, and pMS363 strainsa

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIP | CAZ | FEP | SUL-CFP | ATM | CPR | IPM | MEM | LVX | CIP | |

| WT | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 |

| pMS360 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 1 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 |

| pMS363 | 16 | 64 | ≥32 | ≥32 | 4 | ≥32 | 64 | ≥32 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 |

PIP, piperacillin; FEP, cefepime; SUL-CFP, sulbactam-cefoperazone; CPR, cefpirome; IPM, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; LVX; levofloxacin. MICs were determined using a microbroth dilution method according to the recommendations of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (10).

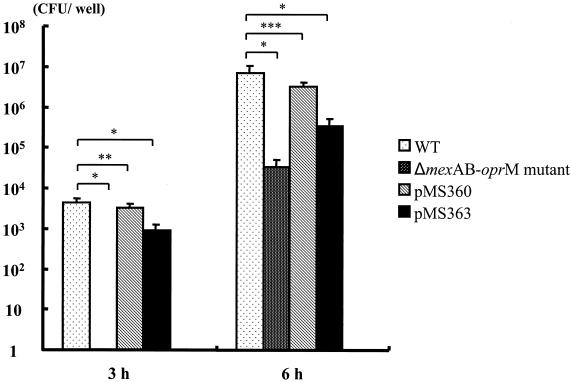

We evaluated the capacity of P. aeruginosa to cause invasive infection by using the MDCK monolayer assay as described previously (2, 5). Although pMS363 could penetrate MDCK cell monolayers by 3 h (Fig. 1), the numbers of pMS363 CFU detected in basolateral medium were less than those of the WT strain. Clinically isolated strains, which have the capacity to cause invasive infections, penetrate MDCK cell monolayers by 3 h (2). Therefore, the differences in capacities to cause invasive infections between pMS363 and the WT did not seem to be practical in spite of the statistical difference in the detected bacterial numbers in the basolateral medium.

FIG. 1.

Extent of penetration of P. aeruginosa WT, ΔmexAB-oprM mutant, pMS360, pMS363, and E. coli RDEC-1 through MDCK cell monolayers at 3 and 6 h after inoculation. Bacteria were inoculated at 3.5 × 107 CFU/well onto apical surfaces of MDCK cell monolayers. The assay was done in triplicate, and results are expressed as averages ± standard deviations. All P. aeruginosa strains except the ΔmexAB-oprM mutant were recovered from basolateral medium by 3 h after inoculation, whereas E. coli RDEC-1 could not be recovered at either time point. Analysis of variance was used for the comparisons among the groups. *, P < 0.001; **, P = 0.068; ***, P = 0.001.

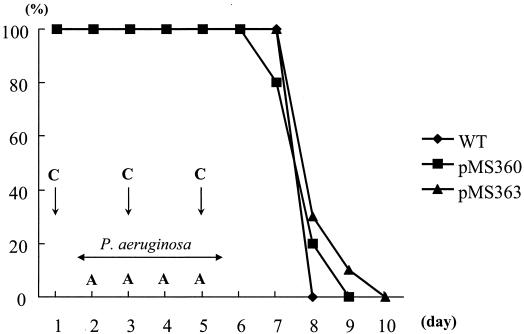

Our observations in mouse models demonstrated this conclusion. The experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Nagasaki University. Male 5-week-old BALB/c specific-pathogen-free mice (Japan SLC Inc., Shizuoka, Japan) were used. Endogenous P. aeruginosa bacteremia was induced as previously described (4), with modifications. All endogenously bacteremic mice died by day 10 (Fig. 2), and similar lethalities were found for the three P. aeruginosa strains. These results suggested that the blaIMP gene raises MICs of β-lactam antibiotics, except that of ATM, for blaIMP-carrying strains but does not decrease the virulence of these strains.

FIG. 2.

Survival kinetics of leukopenic mice given P. aeruginosa strains pMS360, pMS363, and the WT in the endogenous bacteremia model. Mice were given 200 mg of cyclophosphamide (C) and 200 mg of ampicillin (A) per kg on the indicated days. Bacteria were given orally in drinking water in 0.45% saline at 107 CFU/ml between days 2 and 5. The survival rate in the pMS363 bacteremic mouse model was not significantly different from those in the WT (P, 0.0671 by log rank test) and pMS360 (P, 0.4165 by log rank test) models. Also, there was no significant difference between pMS360 and the WT (P, 0.1462 by log rank test).

In a subsequent study, mice were treated with several doses of CAZ (Tanabe Seiyaku Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan), IPM-CS (Banyu Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), and CIP (Bayer AG, Leverkusen, Germany) by intraperitoneal injection twice daily after day 5. These trials were repeated with several concentrations of antibiotics, as indicated below. Mice were observed up to day 12. In the pMS360 mouse bacteremia model, all control mice died by day 9; however, treatment with some concentrations of CAZ increased survival rates (400 mg/kg of body weight/day, 100% survival rate; 200 mg/kg/day, 60%; 6.25 mg/kg/day, 20%). No mice injected with 3.125 mg of IPM-CS/kg/day survived, but higher concentrations of IPM-CS correlated with increased survival rates (25 and 75 mg/kg/day, 80%; 50 mg/kg/day, 60%). In mice treated with CIP, the survival rate rose dose dependently, with a 100% survival rate for the group treated with 40 mg of CIP/kg/day. On the other hand, all saline-treated control mice died by day 9 in the pMS363 mouse bacteremia model. All mice treated with CAZ died by day 11, and not even treatment with 1,000 mg/kg/day rescued the pMS363 bacteremic mice. All mice treated with 3.125 and 25 mg of IPM-CS/kg/day died by days 10 and 11, but other doses of IPM-CS increased survival rates (12.5 and 50 mg/kg/day, 20%; 75 mg/kg/day, 40%). In CIP-treated mice, the survival rates increased dose dependently from 0 (0.15625 mg of CIP/kg/day) to 100% (40 mg of CIP/kg/day). The 50% effective doses (ED50s) of the three antibiotics were thus calculated (Table 2). Although MICs of CAZ and IPM-CS for pMS363 and pMS360 were equivalent, ED50s of CAZ were clearly higher than those of IPM-CS in both mouse models. This may be due to different initial bactericidal activities of CAZ and IPM-CS (9) or different levels of endotoxin release from P. aeruginosa in infections treated with CAZ and IPM-CS (11). The ED50s of CAZ were higher than those of IPM-CS in both models, but those of CIP were almost equal, with CIP being the most effective antibiotic.

TABLE 2.

ED50s of three antibiotics in the mouse endogenous bacteremia model

| Strain | Mean ED50 ± SD (mg/kg/day) (95% confidence interval)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| CAZ | IPM-CS | CIP | |

| pMS360 | 186.9 ± 28.2 (137.2-266.5) | 35.1 ± 7.1 (19.8-53.5) | 10.0 ± 1.7 (6.9-14.8) |

| pMS363 | >1,000 | 91.5 ± 24.7 (62.6-456.3) | 7.1 ± 1.8 (4.3-14.41) |

Although examination of several strains allows generalization, our results showed minor differences, which had insignificant practical influence on virulence, between the P. aeruginosa PAO1 strain carrying blaIMP and the parent strain in vitro and in animal models. CIP was the most potent antibiotic against P. aeruginosa carrying blaIMP in the endogenous bacteremia model. However, CIP resistance is more common than blaIMP in P. aeruginosa, and multidrug-resistant blaIMP-carrying P. aeruginosa isolates with resistance to aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, and β-lactam antibiotics are emerging (6). Therefore, it is necessary to develop new antibiotics with potent activity against multidrug-resistant blaIMP-carrying P. aeruginosa. Currently, it is important to detect metallo-β-lactamase-producing bacteria rapidly and to judge whether or not the pathogens are sensitive to fluoroquinolones.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shizuko Iyobe, Laboratory of Drug Resistance in Bacteria, Gunma University School of Medicine, for kindly providing pMS360 and pMS363. We are grateful to Mariko Mine, Division of Scientific Data Registry, Atomic Bomb Disease Institute, Nagasaki University School of Medicine, for helpful suggestions in statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gibb, A. P., C. Tribuddharat, R. A. Moore, T. J. Louie, W. Krulicki, D. M. Livermore, M. F. I. Palepou, and N. Woodford. 2002. Nosocomial outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa with new a blaIMP allele, blaIMP-7. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:255-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirakata, Y., B. B. Finlay, D. A. Simpson, S. Kohno, S. Kamihira, and D. P. Speert. 2000. Penetration of clinical isolate of Pseudomonas aeruginosa through MDCK epithelial cell monolayers. J. Infect. Dis. 187:765-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirakata, Y., K. Izumikawa, T. Yamaguchi, H. Takemura, H. Tanaka, R. Yoshida, J. Matsuda, M. Nakano, K. Tomono, S. Maesaki, M. Kaku, Y. Yamada, S. Kamihira, and S. Kohno. 1998. Rapid detection and evaluation of clinical characteristics of emerging multiple-drug-resistant gram-negative rods carrying the metallo-β-lactamase gene blaIMP. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2006-2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirakata, Y., M. Kaku, K. Tomono, K. Tateda, N. Furuya, T. Mastumoto, R. Araki, and K. Yamaguchi. 1992. Efficacy of erythromycin lactobionate for treating Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:1198-1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirakata, Y., R. Srikumar, K. Poole, N. Gotoh, T. Suematsu, S. Kohno, S. Kamihira, R. E. W. Hancock, and D. P. Speert. 2002. Multidrug efflux systems play an important role in the invasiveness of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Exp. Med. 196:109-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirakata, Y., T. Yamaguchi, M. Nakano, K. Izumikawa, M. Mine, S. Aoki, A. Kondoh, J. Matsuda, M. Hirayama, K. Yanagihara, Y. Miyazaki, K. Tomono, Y. Yamada, S. Kamihira, and S. Kohno. 2003. Clinical and bacteriological characteristics of IMP-type metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37:26-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iyobe, S., M. Tsunoda, and S. Mitsuhashi. 1994. Cloning and expression in Enterobacteriaceae of the extended-spectrum β-lactamase gene from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa plasmid. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 121:175-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iyobe, S., H. Yamada, S. Minami. 1996. Insertion of a carbapenemase gene cassette into an integron of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa plasmid. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 38:1114-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuda, K., and M. Inoue. 2000. Evaluation of antibiotics by the method of initial bactericidal activity. Jpn. J. Antibiot. 53:667-671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2001. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility testing for bacteria that grow aerobically, 5th ed. Approved standard M7-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 11.Scott, E. B., and D. C. Morrison. 1995. Difference in therapeutic efficacy among cell wall-active antibiotics in a mouse model of gram-negative sepsis. J. Infect. Dis. 172:1519-1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Senda. K., Y. Arakawa, K. Nakashima, H. Ito, S. Ichiyama, K. Shimokata, N. Kato, and M. Ohta. 1996. Multifocal outbreaks of metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistant to broad-spectrum β-lactams, including carbapenems. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:349-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]