Abstract

Sirtuins can promote deacetylation of a wide range of substrates in diverse cellular compartments and regulate many cellular processes1,2. Recently Narayan et al., reported that SIRT2 was required for necroptosis based on their findings that SIRT2 inhibition, knock-down or knock-out prevented necroptosis. We sought to confirm and explore the role of SIRT2 in necroptosis and tested four different sources of the SIRT2 inhibitor AGK2, three independent siRNAs against SIRT2, and cells from two independently generated Sirt2−/− mouse strains, however we were unable to show that inhibiting or depleting SIRT2 protected cells from necroptosis. Furthermore, Sirt2−/− mice succumbed to TNF induced Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) more rapidly than wild type mice while Ripk3−/− mice were resistant. Our results therefore question the importance of SIRT2 in the necroptosis cell death pathway.

There are seven mammalian sirtuins and work has focused on SIRT1, the closest homolog to the founding member of the Sirtuin family, Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sir2. Mammalian SIRT2 has been reported to regulate cellular metabolism, division and differentiation1,2. A recent study suggested an additional role, namely that SIRT2 is required for programmed necrosis, otherwise known as necroptosis3. Using co-immunoprecipitation followed by mass-spectrometric analysis, Narayan et al found that SIRT2 interacted with RIPK3, a kinase that is essential for tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-induced necroptosis4–6. Using a SIRT2 inhibitor, AGK27, they observed that SIRT2 activity was required for formation of the RIPK1/RIPK3 complex in response to the necroptosis inducing stimulus of TNF, the caspase inhibitor, z-VAD-fmk and the translation inhibitor cycloheximide. Narayan et al. proposed that SIRT2-mediated deacetylation of a lysine near the RIPK3-interacting RHIM motif of RIPK1 was required for RIPK1/RIPK3 association and necroptosis induction. Consistent with this hypothesis, they showed that knock-down, knock-out or inhibition of Sirt2/SIRT2 prevented TNF-induced necroptosis in vitro3.

The necroptotic cell death pathway has attracted interest because inhibiting it, particularly in conjunction with blocking apoptosis, has the potential to ameliorate diverse inflammatory and possibly also degenerative diseases8–11. Importantly, Narayan et al. reported that genetic ablation or pharmacological blockade of Sirt2/SIRT2 afforded mice significant protection from injury caused by cardiac ischemia-reperfusion.

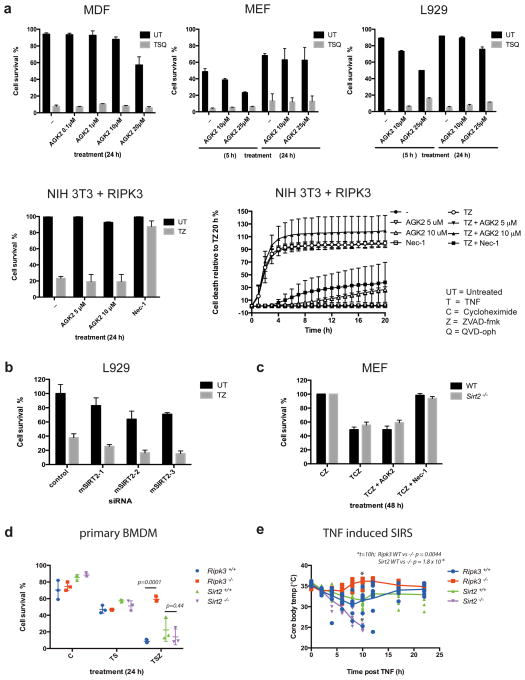

The promise of these findings prompted us to confirm and explore the role of SIRT2 in necroptosis. We tested the ability of four different sources of the SIRT2 inhibitor, AGK2, at a broad range of concentrations, to inhibit necroptosis triggered by TNF+Smac-mimetic+the caspase inhibitor, Q-VD-Oph (TSQ) or TNF+z-VAD-fmk (TZ). In contrast to the findings of Narayan et al., AGK2 failed to inhibit TNF-induced necroptosis in our experiments (Figure 1a & Appendix Figure). As previously described7, AGK2 (SIGMA) increased levels of acetylated-tubulin in NIH-3T3 cells, validating its ability to inhibit SIRT2 at the doses used (Appendix Figure). Narayan et al. found that two independent shRNAs used to knock down Sirt2 expression prevented TZ-induced necroptosis in L929 cells. In our experiments, three independent siRNAs, which reduced Sirt2 expression by greater than 80%, failed to inhibit TZ-induced necroptosis in L929 cells (Figure 1b & Appendix Figure). We also tested mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) from two independently generated Sirt2 knock-out mouse strains (Appendix Figure), but found neither cell type to be protected from TNF-induced necroptotic death (Figure 1c & d).

Figure 1. Neither chemical inhibition nor genetic depletion of SIRT2 inhibits TNF-induced Necroptosis.

a, Indicated cell lines were treated with the indicated necroptotic stimuli in the presence or absence of AGK2. b, L929 cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting SIRT2 or a control siRNA before treatment with TZ. c, MEFs derived from Sirt2−/− and wild-type mice were treated with TCZ ± inhibitors. Plots in panels a–c represent the mean ± standard deviation of two biological repeats (MEFs, MDFs) or the mean ± standard deviation of three independent repeats (L929, NIH 3T3). d, BMDMs isolated from Sirt2+/+, Sirt2−/−, Ripk3+/+ or Ripk3−/− mice (n=3 per genotype) were treated with TSZ. e, Core body temperature of Sirt2+/+, Sirt2−/−, Ripk3+/+ or Ripk3−/− mice (n=10 per genotype) injected with 300 μg/kg TNF. An unpaired students T test was used to determine P values in d, and e.

Finally Narayan et al. observed that Sirt2-deficient mice were protected from cardiac ischaemia-reperfusion injury and concluded that transient inhibition of SIRT2 might provide protection from diseases involving necroptosis. Because RIPK3 deficient mice have not been tested for their ability to resist cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury, we chose to test the response of Sirt2−/− mice to a classic RIPK3-dependent necroptotic insult: we injected wild-type, Ripk3−/−, and Sirt2−/− mice with TNF and monitored their body temperature. As previously described8, the core body temperature of wild-type mice dropped rapidly following injection of 300 μg/kg of TNF, and some of these animals died within the indicated time-frame. In contrast, Ripk3−/− mice maintained normal body temperature and all survived. Far from being protected against this necroptosis-inducing insult, Sirt2−/− mice were more sensitive than their wild-type counterparts, and all died within the indicated time frame (Fig. 1e & Appendix Figure).

These experiments, performed with SIRT2 inhibitors, Sirt2 knock-down cells, Sirt2−/− mice and cells from two independently derived Sirt2−/− mice, raise concerns about the claimed role for SIRT2 in necroptotic cell death.

Methods

Data were generated by nine independent labs. We have endeavored to provide key experimental information, and detailed experimental methods are available on request. AGK2 was sourced from TOCRIS Bioscience (3233), Sigma (A8231), Biovision and the Kazatsev lab7. Cell survival was measured using propidium iodide exclusion and flow cytometric analysis, Cell Titer Glo assay (Promega) and IncuCyte system counting of SYTOX® green positive cells in real time. Sirt2−/− mice were provided by the Donmez and Auwerx labs12,13. TNF was sourced from Peprotech or made in house. Published protocols for siRNA, BMDM maturation and SIRS experiments were followed8,x,x.

Supplementary Material

5 sentences; first sentence sets the scene, the second summarises the results of the Nature paper under discussion, the third & 4th presents your contradictory view/results, and the fifth states the implications.

References

- 1.Houtkooper RH, Pirinen E, Auwerx J. Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism and healthspan. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2012;13:225–238. doi: 10.1038/nrm3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sebastian C, Satterstrom FK, Haigis MC, Mostoslavsky R. From sirtuin biology to human diseases: an update. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:42444–42452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.402768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narayan N, et al. The NAD-dependent deacetylase SIRT2 is required for programmed necrosis. Nature. 2012;492:199–204. doi: 10.1038/nature11700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho YS, et al. Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell. 2009;137:1112–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He S, et al. Receptor interacting protein kinase-3 determines cellular necrotic response to TNF-alpha. Cell. 2009;137:1100–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang DW, et al. RIP3, an energy metabolism regulator that switches TNF-induced cell death from apoptosis to necrosis. Science. 2009;325:332–336. doi: 10.1126/science.1172308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Outeiro TF, et al. Sirtuin 2 inhibitors rescue alpha-synuclein-mediated toxicity in models of Parkinson’s disease. Science. 2007;317:516–519. doi: 10.1126/science.1143780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duprez L, et al. RIP kinase-dependent necrosis drives lethal systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Immunity. 2011;35:908–918. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunther C, et al. Caspase-8 regulates TNF-alpha-induced epithelial necroptosis and terminal ileitis. Nature. 2011;477:335–339. doi: 10.1038/nature10400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piao X, et al. c-FLIP maintains tissue homeostasis by preventing apoptosis and programmed necrosis. Science signaling. 2012;5:ra93. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welz PS, et al. FADD prevents RIP3-mediated epithelial cell necrosis and chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2011;477:330–334. doi: 10.1038/nature10273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beirowski B, et al. Sir-two-homolog 2 (Sirt2) modulates peripheral myelination through polarity protein Par-3/atypical protein kinase C (aPKC) signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:E952–961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104969108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bobrowska A, Donmez G, Weiss A, Guarente L, Bates G. SIRT2 ablation has no effect on tubulin acetylation in brain, cholesterol biosynthesis or the progression of Huntington’s disease phenotypes in vivo. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.